Given that tobacco smoking is the leading preventable cause of death in the United States, reducing smoking rates is one of the nation’s highest public health priorities. Doing so would lower deaths and illness caused by tobacco products, decrease related health care costs, and improve the quality and length of life of individuals. Although great strides have been made since the landmark Surgeon General’s report in 1964, almost 18 percent of the U.S. population still smokes (Agaku et al., 2014; Jamal et al., 2014). The environment in which tobacco products are used and sold is complex and evolving, and requires working across multiple sectors and understanding an intricate web of stakeholders including a diverse user population, largely addicted to tobacco products. Understanding this tobacco landscape is essential when attempting to model tobacco control policies to inform policy decision making. This chapter provides a snapshot of these issues, including policy inputs and context that will be reviewed in this report, a review of what is currently understood about tobacco use behavior, and why agent-based models (ABMs) could be a useful tool for exploring tobacco-related questions.

The tobacco regulatory environment is complicated, and when the intricate web of other actors (or agents) is considered, tobacco regulation can be viewed as a complex adaptive system. Modeling is a useful tool for understanding the structure and behavior of complex adaptive systems, which are defined by Plsek and Greenhalgh (2001, p. 625) as “a collection

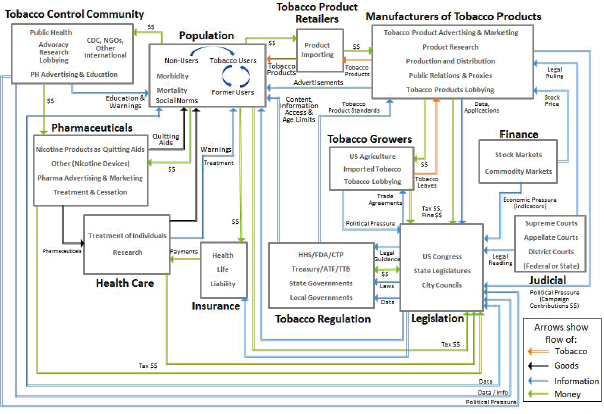

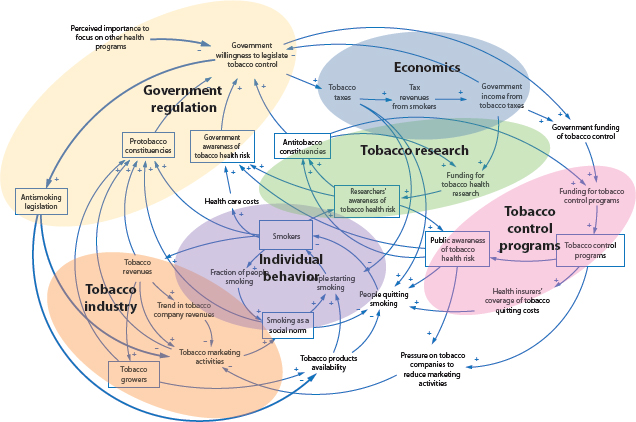

of individual agents with freedom to act in ways that are not always totally predictable, and whose actions are interconnected so that one agent’s actions changes the context for other agents.” Components of these systems can be studied separately, but there are relationships among them, so the behavior of each component depends on the behavior of others. Below the committee highlights some of the complex relationships among various stakeholders that are particularly relevant to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) today. See Figures 2-1 and 2-2 for depictions of these relationships, highlighting different aspects of the complex tobacco system. Figure 2-1 illustrates the web of relationships in the tobacco environment, which consists of varied agents in the system, including regulators, tobacco retailers, the tobacco control community, health care, and others. Figure 2-2 displays the many feedbacks that operate among various groups and entities within the tobacco control environment, including tobacco research, individual behavior, tobacco control programs, tobacco industry, and economics.

The Complex Tobacco Problem

Tobacco has been referred to as a wicked problem (APSC, 2007; Dorfman and Wallack, 1993; Young et al., 2012). Originally coined by Rittel and Webber (1973), a wicked problem has more recently been defined as “a social or cultural problem that is difficult or impossible to solve for as many as four reasons: incomplete or contradictory knowledge, a large number of people and opinions involved, the important economic burden, and the interconnected nature of these problems with other problems” (Kolko, 2012). Wicked problems can productively be viewed within the environment of the larger complex adaptive system, which describes the wider landscape that surrounds and influences the problem. Wicked problems cannot be approached solely with analytical approaches, nor can they be managed by a single organization, jurisdiction, or domain (Young et al., 2012). Classic examples of wicked problems include poverty, climate change, and land degradation; the problem of obesity is an example of such a problem that has arisen more recently. Tobacco is viewed as a wicked problem because of the often contradictory goals of stakeholders that give rise to uncertainty and because of the addictive nature of tobacco products.

Five years ago, FDA was given an unprecedented opportunity to regulate tobacco, but the complex nature of tobacco control remains an impediment to clear-cut and effective policy implementation. (See later in this chapter for a discussion of FDA’s regulatory authorities.) FDA’s steps toward comprehensive tobacco regulation have been gradual for a number of reasons. The Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act (Tobacco Control Act) was enacted only 5 years ago, so the agency is still developing its strategy and focus. One of the first—and key—regulatory

FIGURE 2-1 Agents and relationships within the tobacco control landscape.

NOTES: ATF = Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives; CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CTP = Center for Tobacco Products; FDA = U.S. Food and Drug Administration; HHS = U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; NGO = nongovernmental organization; PH = public health; TTB = Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau.

SOURCE: SNL, 2014.

FIGURE 2-2 Complex tobacco landscape.

NOTE: This figure is not drawn to scale, nor is any meaning implied by the relative sizes of elements within the figure. See Kirkwood (1998) for more information about causal loop diagram construction.

SOURCE: NCI, 2007, adapted by Luke, 2013.

efforts, the move to put graphic warning labels on packs of cigarettes, was at least temporarily thwarted by the tobacco industry.1 Other facets of FDA’s regulatory authority over tobacco, such as reducing the nicotine content of regulated products and banning menthol, remain largely untested. FDA is also limited as to how and what it can regulate based on the act. For instance, it cannot eliminate nicotine content in tobacco products or regulate products geared toward cessation, and some decisions, such as tobacco retailer density, are made at the state or local level.

Furthermore, as is the case with other federal agencies, FDA has congressional oversight accompanied by ongoing discussions regarding modification of the Tobacco Control Act (NACS, 2014). In addition, the regulatory process requires considerable public input, which means that any proposed regulation must be posted for public comment for a period that is generally between 30 and 60 days but can, in some cases, be longer (OFR, 2014). Because many policies promulgated by the agency are likely to be brought to court, FDA must often plan for at least the risk of legal challenges (TCLC, 2014c). In addition to the case of graphic warning labels, FDA has already faced major court challenges. In 2010, in the case Sottera, Inc. v. FDA,2 a federal court ruled against FDA’s attempt to expand its authority to electronic cigarettes by deeming them a medical drug-device, which would fall under FDA’s jurisdiction under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act).3 More recently, a suit was filed by Lorillard and R.J. Reynolds challenging a CTP menthol report (TPSAC, 2011) on the grounds that several members of the FDA’s Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee (TPSAC), many of whom contributed to the report, had conflicts of interest. In July 2014, a District Court judge ruled that CTP could not use the 2011 report and that the membership of TPSAC should be reconstituted.4 FDA has filed a notice of appeal to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit (TCLC, 2014c).

As tobacco products continue to be introduced, FDA and other members of the tobacco control community face evolving challenges and uncertainty. The tobacco control community includes other federal agencies, such

_____________________

1Five tobacco manufacturers filed suit in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia to challenge the FDA’s final regulation governing graphic warning labels for cigarettes on August 16, 2011. The court found that the graphic warning rule unconstitutionally limited the tobacco companies’ right to freedom of speech (R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. v. United States Food & Drug Admin., 845 F.Supp.2d 266 (D.D.C. 2012)). On appeal, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit upheld the district court’s finding that the graphic warning requirement was unconstitutional (R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. v. United States Food & Drug Admin., 696 F.3d 1205 (D.C. Cir. 2012)).

2Sottera Inc v. FDA, 627 F.3d 891 (D.C. Cir. 2010).

3Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (“FD&C Act”), 21 U.S.C. § 351 et seq.

4Lorillard, Inc., et al., v. FDA, et al., No. 11-440 (D.C. Cir. 2014).

as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and advocacy and nonprofit organizations such as Legacy and Campaign Tobacco Free Kids. Although the tobacco control community has a general mission to curb the tobacco epidemic, actors within the tobacco control community have different mechanisms with which to combat tobacco use. Advocacy groups, for example, can use political pressure to fight to reduce tobacco use. These various types of groups sometimes disagree regarding the most effective approach to combat tobacco use, particularly when there are limited data and uncertainty in research findings. Disagreement among experts can delay policy making. Electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) are a relevant example. Some public health officials argue that e-cigarettes may help smokers quit smoking or reduce harm by encouraging smokers to smoke fewer cigarettes (Abrams, 2014; Fairchild et al., 2014; Hajek, 2013). But others are concerned that the use of e-cigarettes may result in delayed or deferred quitting, renormalize smoking behaviors, and lead to the continuing sales of conventional cigarettes (Bhatnagar et al., 2014; Grana et al., 2014).

Tobacco growers, manufacturers of tobacco products, and tobacco product retailers continue to facilitate the production, distribution, and promotion of tobacco products. To counter antitobacco efforts, tobacco-manufacturing groups have invested billions in advertisements and promotions, including payments to retailers and pharmacies.5 Tobacco growers and manufacturing groups have leveraged political ties through campaign contributions and lobbying and brought lawsuits to block antitobacco legislation (Morley et al., 2002). They have also collaborated with other industries, such as the hospitality industry, to challenge comprehensive clean indoor air laws (Traynor et al., 1993), and with financial analysts from the investment bank industry to promote the tobacco industry’s public policy agenda (Alamar and Glantz, 2004; Tsoukalas and Glantz, 2003). As the market for alternative tobacco products grows, new stakeholders, such as e-cigarette companies and trade associations, have emerged. The Smoke Free Alternatives Trade Association, for example, engages lobbyists at the federal and state levels to block potentially threatening legislation related to vapor products and aims to reinforce the distinctions between vapor and tobacco products and their two respective industries (SFATA, 2015). Meanwhile, tobacco manufacturers have acquired e-cigarette companies and have test marketed their own e-cigarette products (Bauld et al., 2014).

Many other players and infrastructure are linked to—and, in some cases, dependent on—tobacco products. Retail, drug, and vape stores as well as shipping and marketing companies can derive considerable profit from tobacco products. Furthermore, state and local governments often

_____________________

5An exception: in September 2014, CVS/Caremark was the first pharmacy to stop selling tobacco products.

benefit considerably from tobacco taxes and also receive tobacco settlement funds in varying degrees (NAAG, 1998), thus mitigating their incentive to eliminate tobacco use. Pharmaceutical companies that develop and sell cessation products may also be concerned with a cut in profits if dramatic tobacco reductions occur.

Finally, there are the 42 million current smokers in the United States (HHS, 2014b). Individuals start, maintain, and stop the use of tobacco for a variety of reasons. For example, adolescents may experiment with smoking because of peer pressure or social norms, whereas others may use tobacco regularly to relieve stress. Some demographic groups have particularly high smoking prevalence. Adults with mental illness, for instance, are approximately twice as likely to smoke as those who have not been diagnosed with mental illness (Gfroerer et al., 2013; Lasser et al., 2000), potentially to self-medicate, regulate moods, and mitigate stress (Ziedonis et al., 2008). Smoking prevalence among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals in the United States is also significantly higher than in the general population (Fallin et al., 2014; King et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2009); this may be due to stigma, discrimination, and stress (Blosnich et al., 2013; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2011) or to being targeted by tobacco industry marketing efforts (Dilley et al., 2008; Stevens et al., 2004; Washington, 2002) or by media (Lee et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2006), or other reasons (Pokhrel and Caine, 2012). Whatever the reason for using tobacco products, many of these smokers are likely to become addicted, specifically to nicotine. However, addiction affects individuals differently depending on several factors, such as the age of initiation and genetic susceptibilities, meaning individuals may differ in their abilities to quit (Benowitz, 2008a). Furthermore, barriers to cessation treatments and support services that may be experienced by some populations, such as ethnic minorities and people from low socioeconomic backgrounds, may reduce the success rates of quitting (Fu et al., 2007; Malarcher et al., 2011; TUDGP, 2008). The continual introduction of new tobacco products in the market, such as electronic nicotine delivery devices, adds another layer of complexity.

This brief summary provides only a glimpse of the complex tobacco landscape. The multiple players, interdependencies, unintended side effects, and contradictions in an evolving environment that make tobacco a wicked problem complicate the process of finding and implementing ways to reduce tobacco use. Even when a solution seems to have been found, unintended consequences may emerge. In effect, creative methods that can anticipate alternative scenarios and unforeseen consequences could be useful. These considerations lead to the use of analytical methods to understand the current policy options and the effects of those policies and to predict the effect of potential new tobacco regulatory policies. ABMs may be one such method. To understand how major stakeholders in tobacco control, such as

FDA, could use and gain from modeling, it is important to further examine the regulatory approaches and potential policies for tobacco products. (See the final section of this chapter for a discussion on how ABMs could be useful tools for informing tobacco control policy.)

REGULATORY AUTHORITY FOR TOBACCO PRODUCTS

Across the United States there are many policies and interventions in place meant to reduce tobacco use either by preventing initiation or by encouraging cessation. These policies have been put in place by federal, state, and local governments. This report focuses on the policies or interventions under the purview of FDA. However, actions by others in the tobacco regulatory environment can affect policies put forth by FDA, so these are briefly outlined in this chapter as well.

Federal Regulation of Tobacco Products

U.S. Food and Drug Administration

As of 2009, the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act6,7 (the Tobacco Control Act) gave FDA (part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [HHS]) broad authority to regulate the manufacturing, marketing, and sale of tobacco products, including cigarettes, cigarette tobacco, “roll-your-own” tobacco, and smokeless tobacco products (see Box 2-1 for highlights from the Tobacco Control Act).8 Recently, FDA proposed regulations to extend its authority to regulate other tobacco products. FDA oversees the implementation of the Tobacco Control Act through a variety of mechanisms. For example, FDA developed CTP to implement TPSAC to provide advice, information, and recommendations to FDA. Additionally, FDA assesses and collects user fees from tobacco product manufacturers and importers based on their market share, and uses the money to fund FDA activities related to the regulation of tobacco

_______________________

6Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act of 2009, Public Law 111-31, 111th Cong. (June 22, 2009).

7The Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act was expanded to include the Tobacco Control Act; see Subchapter IX—Tobacco Products (sections 387–387u).

8Two other major tobacco acts preceded the Tobacco Control Act. The Federal Cigarette Labeling and Advertising Act (FCLAA) of 1966, 15 U.S.C. § 1335a(a), Public Law 89-92, was amended by the Comprehensive Smoking Education Act (CSTHEA) of 1986, 15 U.S.C. § 4401-4408, Public Law 99-252 (February 27, 1986). CSTHEA, as amended by the 2009 Tobacco Control Act, “requires manufacturers, packagers, and importers of cigarettes to place one of four statutorily-prescribed health-related warnings on cigarette packages and in advertisements, on a rotating basis.” CSTHEA prohibits any advertising of smokeless tobacco products on radio and television.

BOX 2-1

Highlights from the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act

- Seeks to prevent and reduce tobacco use by young people

- Recognizes that tobacco products are legal products available for adult use

- Prohibits false or misleading labeling and advertising for tobacco products

- Allows FDA to establish product standards and to require scientific evidence for any claims of reduced exposure and harm

- Provides the tobacco industry with some mechanisms to submit an application to FDA for new products or tobacco products with modified risk claims

- Grants FDA enforcement authority and general set of sanctions for violations of the law and allows FDA to contract with states to support FDA with retailer inspections

SOURCE: FDA, 2014.

products.9 FDA also issues regulations and conducts inspections to investigate illicit trade in tobacco products.10 A detailed list of what the FDA does and does not have authority over is described below in five categories: manufacturing, marketing, sales, limitations, and new tobacco products. (The following sections on manufacturing, marketing, and sales are largely excerpted from FDA, 2014.)

Manufacturing FDA has the authority to oversee several areas regarding manufacturing, including (FDA, 2014):

- Registration and inspection of tobacco companies

- —Requiring owners and operators of tobacco companies to register annually and be subject to inspection every 2 years by FDA

- Standards for tobacco products

- —Allowing FDA to require standards for tobacco products (e.g., tar and nicotine levels) as appropriate to protect public health

_______________________

9The Tobacco Control Act user fee program will generate more than $4.5 billion in user fees over 9 years (2009–2018) (FDA, 2009). FDA spent (obligated) less than half of the $1.1 billion in tobacco user fees it collected from manufacturers and others from fiscal year 2009 through the end of fiscal year 2012 (Crosse, 2014).

10For more information on the illicit tobacco market in the United States, see NRC (2015), Understanding the U.S. Illicit Tobacco Market: Characteristics, Policy Context, and Lessons from International Experiences.

-

- —Banning cigarettes with characterizing flavors, except menthol and tobacco

- “Premarket Review” of new tobacco products

- —Requiring manufacturers who wish to market a new tobacco product to obtain a marketing order from FDA prior to marketing that new product11

- Modified risk products

- —Requiring manufacturers who wish to market a tobacco product with a claim of reduced harm to obtain a marketing order from FDA

- Requiring tobacco companies to disclose research on the health, toxicological, behavioral, or physiologic effects of tobacco use

- —Requiring tobacco companies to disclose information on ingredients and constituents in tobacco products and to notify FDA of any changes

Marketing FDA has some authority related to tobacco product advertising aimed at youth, the use of certain claims regarding tobacco, use of warning labels, and enforcement of policies made in this area, including (FDA, 2014):

- Restricting tobacco product advertising and marketing to youth

- —Limiting the color and design of packaging and advertisements, including audiovisual advertisements12

- —Banning tobacco product sponsorship of sporting or entertainment events under the brand names of cigarettes or smokeless tobacco

- —Banning free samples of cigarettes and brand-name non-tobacco promotional items

- Prohibiting “reduced harm” claims, including “light,” “low,” or “mild,” without an FDA order to allow marketing

- —Requiring industry to submit marketing research documents

- Requiring bigger, more prominent warning labels for cigarettes and smokeless tobacco products

- —Packaging and advertisements for cigarettes and smokeless tobacco must have revised warning labels with a larger font size.

_______________________

11When a manufacturer obtains a marketing order, the manufacturer has complied with the requirements under the FD&C Act to bring its product to market. While FDA may issue a marketing order for a tobacco product to be marketed, the order does not necessarily mean that the tobacco product is safe or “approved” (FDA, 2015b; Miner, 2012).

12The implementation of the provision is uncertain due to pending litigation.

-

-

Font colors are limited to white on a black background or black on a white background.

- —Cigarette package health warnings will be required to cover the top 50 percent of both the front and rear panels of the package, and the nine specific warning messages must be equally and randomly displayed and distributed in all areas of the United States. These messages must be accompanied by color graphics showing the negative health consequences of smoking cigarettes.

- —Smokeless tobacco package warnings must cover 30 percent of the two principal display panels, and the four specific required messages must be equally and randomly displayed and distributed in all areas of the United States.

-

- Creating an enforcement action plan for advertising and promotion restrictions

- —FDA published a document titled “Enforcement Action Plan for Promotion and Advertising Restrictions” (FDA, 2010).

- —The action plan details FDA’s current thinking on how it intends to enforce certain requirements under the Tobacco Control Act.

Although not explicitly stated in the Tobacco Control Act, FDA may develop and disseminate public education campaigns that inform the public about the dangers of tobacco products. In February 2014, FDA launched nationally its first youth tobacco prevention campaign, called “The Real Cost,” across multiple media platforms, including television, radio, print, and online (FDA, 2015a). The goal of the campaign is to educate at-risk youth aged 12 to 17 who are open to smoking or already experimenting with cigarette use and, by educating them, reduce initiation rates and the prevalence of tobacco use among this population. The campaign will air in more than 200 markets across the country for more than 1 year. In the coming years, FDA plans to develop more youth tobacco prevention campaigns that will target other audiences, including multicultural, rural, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youths (Hamburg, 2014).

Sales FDA can also impose restrictions on the retail sales to youth of cigarettes and smokeless tobacco, including (FDA, 2014):

- Requiring proof of age to purchase these tobacco products (the federal minimum age to purchase is 18)

- Requiring face-to-face sales, with certain exemptions for vending machines and self-service displays in adult-only facilities

- Banning the sale of packages of fewer than 20 cigarettes

Limitations FDA does not have the authority to ban certain specified classes of tobacco products,13 to require the reduction of nicotine yields in tobacco products to zero, to require prescriptions to purchase tobacco products, to reduce the minimum age to purchase tobacco products, or to ban face-to-face tobacco sales in any particular category of retail outlet. The Tobacco Control Act also preserves the authority of state, local, and tribal governments to regulate tobacco products in certain specific respects. It prohibits, with certain exceptions, state and local requirements that are different from, or in addition to, requirements under the provisions of the FD&C Act relating to specified areas.14

New tobacco products The Tobacco Control Act defines a tobacco product as any product “made or derived from tobacco” that is not a drug, device, or combination product. In April 2014, FDA proposed to deem all products that meet the definition of a tobacco product to be subject to the FD&C Act, as amended by the Tobacco Control Act (HHS, 2014a). This would either cover “all other categories of products, except accessories of a proposed deemed tobacco product, that meet the statutory definition of ‘tobacco product’ in the FD&C Act” or else “extend the Agency’s ‘tobacco product’ authorities to all other categories of products, except premium cigars and the accessories of a proposed deemed tobacco product, that meet the statutory definition of ‘tobacco product’ in the FD&C Act” (HHS, 2014a, p. 23142). The newly covered products would include e-cigarettes, cigars, pipe tobacco, and hookah tobacco. Now that a 105-day public comment period has ended as of August 8, 2014, FDA will review the comments before issuing a final regulation (TCLC, 2014a,b). If finalized in its current form, the deeming rule will give FDA the authority to restrict the sale of newly covered tobacco products to minors below the age of 18, prohibit their sales in vending machines except in adults-only venues, prohibit free samples, and require a health warning on package labels (TCLC, 2014b). However, FDA would not automatically claim the authority to restrict the marketing of newly covered products (except false or misleading advertising) or prohibit the use of flavorings such as in e-cigarettes, even though it can do so for traditional cigarettes. FDA would retain the authority to take these actions in the future (TCLC, 2014b).

_______________________

13FDA cannot ban all cigarettes, all smokeless tobacco products, all little cigars, all cigars other than little cigars, all pipe tobacco, or all roll-your-own tobacco products.

14Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938, Chapter IX. Public Law 75-717, 75th Cong. (1938).

Roles of Other Federal Agencies for Tobacco

Other federal agencies are involved in tobacco regulation in various ways, including prevention, enforcement, cessation, and compliance (Leischow et al., 2010). The Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, a department within FDA, plays a significant role in the regulation of smoking cessation medications. Other agencies within HHS with tobacco-related responsibilities include CDC;15 the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration;16 the National Institutes of Health, including the National Cancer Institute17 and the National Institute on Drug Abuse;18 the Health Resources and Services Administration;19 the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services;20 and the Indian Health Service.21 Within HHS, the departments that have tobacco-related responsibilities have regular meetings to foster communication across the department (Leischow et al., 2010). Other agencies that have tobacco-related responsibilities include the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau;22 the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco,

_____________________

15“CDC, through the Office on Smoking and Health (OSH), is the lead federal agency for comprehensive tobacco prevention and control. OSH is a division within the National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, which is located within CDC’s Coordinating Center for Health Promotion. Originally established in 1965 as the National Clearinghouse for Smoking and Health, OSH is dedicated to reducing the death and disease caused by tobacco use and exposure to secondhand smoke” (CDC, 2014b).

16The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration oversees implementation of the Synar Amendment, which requires states to have laws in place prohibiting the sale and distribution of tobacco products to minors, and the enforcement of those laws.

17The National Cancer Institute’s Tobacco Control Research Branch leads and collaborates on research and disseminates evidence-based findings to prevent, treat, and control tobacco use. Additionally, in partnership with Legacy, the National Cancer Institute created the Tobacco Research Network on Disparities to help facilitate the elimination of health disparities related to tobacco.

18The National Institute on Drug Abuse works with FDA and supports a wide variety of research on tobacco from basic science to tobacco control policy.

19The Health Resources and Services Administration aims to have 100 percent of its health center grantees adopt formal tobacco prevention and cessation programs.

20The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services cover treatment of tobacco-related illness and cessation counseling in certain circumstances.

21The Tobacco Control and Prevention Program of the Indian Health Service seeks to improve the physical, mental, social, and spiritual health of American Indians and Alaska Natives through the prevention and reduction of tobacco-related disease.

22The Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (under the U.S. Department of Treasury) assures compliance with federal tobacco permitting and collects federal tobacco taxes.

Firearms and Explosives;23 the Federal Trade Commission;24 and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.25

State, Local, and Tribal Authority

As noted earlier, the Tobacco Control Act preserves the authority of state, local, and tribal governments to regulate tobacco products in certain specific respects. Under the new law, state and local governments can engage in a large array of tobacco policies aimed at reducing tobacco use and improving health in addition to authorities they had before the law was passed (such as taxation). They can use communication interventions to convey the risks and harms of tobacco through many avenues, including print, other media, and the Internet. They can also engage in and increase access to cessation programs aimed at helping tobacco users stop. Other levers often used by states and localities include raising tobacco taxes (which range from a low of 17 cents per pack in Missouri to a high of $4.35 per pack in New York) (Henchman and Drenkard, 2014); passing smoke-free laws that apply to restaurants, bars, and workplaces; restricting the sale, distribution, and possession of tobacco products; and implementing tax evasion and anti-smuggling measures (CDC, 2014a; TCLC, 2009). The Tobacco Control Act permits state and local governments to:

- Expand the current requirements of the Tobacco Control Act that limit advertisements for cigarettes and smokeless tobacco to black- and-white text to apply to advertisements for cigars and other tobacco products as well

- Prohibit the display of “power walls” of cigarette packages at retail outlets

- Limit the number and size of tobacco advertisements at retail outlets

- Require that tobacco products (and advertisements) be kept a minimum distance from cash registers

States and localities can also impose minimum age and other sale restrictions, retail density laws, fire-safe laws, reporting requirements (such as ingredients), and point-of-sale warnings, among others. However, they can-

_____________________

23Under the U.S. Department of Justice, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives aims to “reduce alcohol smuggling and contraband cigarette trafficking activity, divest criminal and terrorist organizations of monies derived from this illicit activity and significantly reduce tax revenue losses to the States” (ATF, 2015).

24The Federal Trade Commission investigates unfair tobacco industry business practices and advertisements and enforces laws that address these practices.

25The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency regulates pesticides used on tobacco plants.

not place requirements on cigarette or smokeless tobacco product labeling or on the content of cigarette or smokeless tobacco advertisements; those are under the jurisdiction of FDA.

Finally, the nations of Indian Country, as sovereign entities, have significant regulatory powers over tobacco. Multiple tribes now produce, market, and sell tobacco products and view the manufacturing and sales of tax-free tobacco products as a revenue opportunity, a benefit to tribal economic development, and, perhaps most importantly, an exercised right of their sovereign statuses. State excise taxes do not apply to cigarettes sold to tribal members on tribal land (Samuel et al., 2012). Furthermore, even though federal law requires the collection and remittance of excise taxes of cigarette sales to non-tribal members, states cannot force tribes to collect them (Samuel et al., 2012). Thus, cigarettes sold on reservations may not include any state excise taxes, resulting in significantly lower costs for consumers (Hyland et al., 2005). One result of these low costs is that individuals or sellers on the black market skirt taxes by purchasing cigarettes on reservations (Kurti et al., 2012). It is important to note that although states have no authority over tribal nations, many states and tribes have entered into compact agreements regarding taxation.26 The federal government has regulatory authority over tribal tobacco products, but the extent of this authority is still somewhat unclear.

To use computational modeling effectively to examine the impact of policy or interventions on tobacco use, modelers need to understand not only the tobacco environment but also tobacco use behavior by individuals. This section provides a high-level overview of some of the theoretical and empirical concepts about initiation and cessation of tobacco use among youth and adults and discusses characteristics of tobacco products, particularly their addictive nature, that are important to consider when developing a computational model. The onset, progression, and cessation of tobacco use among youth and adults are complex and multifactor processes, and they have been conceptualized from the perspective of many different fields, including brain disease, genetics, economics, psychology, and sociology. Among the various perspectives, this section focuses primarily on key drivers from the social and behavioral sciences because there is a large body of literature looking at tobacco-related behavior from these perspectives. It deserves mention, however, that perspectives from other fields have been responsible for major contributions to understanding tobacco use behavior, and these need

_____________________

26For more information on tribal tax codes and agreements, see NCAI, 2015, and https://www.sos.ok.gov/gov/tribal.aspx.

to be taken into account when attempting to predict responses to policies. The perspectives used in this chapter will vary, depending on the particular question being addressed.

Tobacco Use—Factors to Be Considered When Developing Models

Tobacco use is a complex behavior that is determined by a wide range of factors that need to be considered in assessing a policy’s effects on the prevalence of tobacco use and its health consequences. Tobacco use initiation and tobacco use cessation are understood to be distinct multistep processes that are influenced by different but sometimes overlapping factors. For example, the reasons that people initiate the use of tobacco products (e.g., social influence) are often different from their reasons for continuing to use the products (e.g., addiction). The goal of this section is to summarize the current understanding of some of the factors leading to behavior change that policy makers need to consider when predicting or assessing the impact of tobacco control interventions. Computational models designed to forecast the effects of tobacco policies need to take these factors into account early in the development process as part of the conceptual framework.

Biological, psychological, social–contextual, and economic factors, among others, contribute to the development, maintenance, and change of health behavior patterns such as tobacco use. Conceptual frameworks and theories offer systematic ways of understanding key determinants of behaviors and guide the search to identify the data and information that are needed to predict behavior. For example, cognitive–behavioral models (Glanz et al., 2005)27 are drawn from the social and behavioral sciences. Examples include the health belief model28 (Hochbaum, 1958) and social cognitive theory29 (Bandura, 1986), which have been used to predict tobacco use behavior at the intrapersonal levels and interpersonal levels, respectively. Empirical testing of these theories has established that the constructs included in these models influence initiation (HHS, 2014b)

_____________________

27Cognitive–behavioral models are based on the assumptions that behavior is mediated by cognitions (i.e., what people know and think affects how they act); knowledge is necessary for, but not sufficient to produce, most behavior changes; and perceptions, motivations, skills, and the social environment are key influences on behavior (Glanz et al., 2005).

28The theory suggests that health behavior is determined by personal beliefs or perceptions about a disease and the approaches available to decrease its occurrence. Four perceptions serve as the main constructs of the health belief model: perceived seriousness, perceived susceptibility, perceived benefits, and perceived barriers. Each of these perceptions, individually or in combination, can be used to explain health behavior. The model has added other constructs, including cues to action, motivating factors, and self-efficacy (Hayden, 2014).

29This theory posits that health is a function of factors that exist across intrapersonal, interpersonal, and community levels.

and cessation of tobacco use (Prochaska et al., 2008). Empirical research has also established a number of biological mechanisms relevant to tobacco use behavior at the intrapersonal level, particularly tobacco use cessation. For example, genetic susceptibility to nicotine and the physiologic pathways specific to serotonin and dopamine receptors and processing in the brain influence an individual’s ability to quit tobacco use (HHS, 2010). Finally, factors such as time preference and discount rates (i.e., how individuals value costs and benefits that occur in the future versus those in the present), risk aversion, price, marketing, the development of information on the harms of smoking, provision of information by the government, social networks, and behavioral economics concepts such as heuristics all are considered in economic models and empirical analyses aimed at understanding tobacco use behavior (Cawley and Ruhm, 2011; Chaloupka, 1991; Chaloupka and Warner, 2000; Smith et al., 2014).

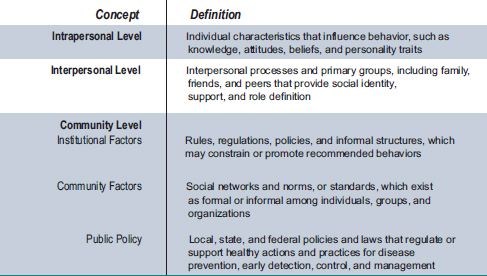

Although a variety of conceptual frameworks and theories have been used in efforts to understand tobacco use behavior, many of them have emphasized an ecological perspective, which asserts that an individual’s behavior both shapes and is shaped by the social environment (Bandura, 1986; McLeroy et al., 1988; Sallis et al., 2008). In other words, an individual’s behavior is understood to affect and be affected not only by intrapersonal characteristics such as knowledge, attitudes and beliefs, but also by interpersonal factors like peer influence and community-level factors like social norms and policies (see Figure 2-3).

FIGURE 2-3 An ecological perspective: Levels of influence.

SOURCE: Glanz et al., 2005.

Moreover, the factors influencing tobacco use at the intrapersonal, the interpersonal, and the community levels interact in a complex web, with the factors both acting directly on tobacco use behaviors and also altering each other’s impact on tobacco use behavior.30 The next section uses an ecological perspective to highlight the salient factors that drive initiation and cessation of tobacco use—and, specifically, of cigarette smoking, because most studies to date have focused on cigarette smoking. The ecological perspective is often used in public health to frame complex behavior, and so it is used in the following section to guide the discussion on tobacco use initiation and cessation. However, it is important to note that there are other perspectives in the research literature that can be valuable when studying tobacco use behavior, such as those from biology or economics, and perspectives from these fields are included where appropriate.

Smoking Initiation

The onset and progression of tobacco use among young people, from adolescence into young adulthood, is a dynamic, multistage process influenced by multiple determinants. As shown in Figure 2-3, these determinants operate at intrapersonal, interpersonal, and other (e.g., social, community, public policy) levels. Adolescence and young adulthood are critical periods in the life course when tobacco use may be especially appealing and even functional, as substantial research indicates that it is not merely a “rational choice” in these developmental phases. Developmentally speaking, young people progress from experimentation with tobacco use, to intermittent use, to regular use and dependence. Not all young people progress through all stages, and movement across these stages can be both forward and backward. Nearly 90 percent of adult daily smokers report that they started using cigarettes before the age of 18, and two-thirds made the transition to daily use during adolescence (HHS, 2012). Longitudinal studies show that it takes 3 years on average to move from experimentation to regular (i.e., daily) use, with considerable variation between individuals in both the process and the timing (HHS, 2012; Mayhew et al., 2000). Before and during each of these stages, attitudes and beliefs about the utility of tobacco use are formed that can drive movement forward or backward between stages. Identifying key factors that drive continued use or that interrupt progress

_____________________

30One variable may mediate the effect (i.e., be on the causal pathway) of a second variable’s influence on tobacco use initiation or cessation. For example, social norms about tobacco use in a particular school can alter peer influence in that school, which in turn will affect the initiation of tobacco use among the youth in that school. Alternately, variables can moderate (i.e., change) the strength of the relationship between a second variable and tobacco use. For example, the impact of peer influence on tobacco use initiation among youth may be moderated by the effects of parent tobacco use at home.

along this continuum will be critical to any modeling process designed to predict tobacco use behaviors in young populations.

At the intrapersonal level, beliefs about the health and social consequences of tobacco use, decision-making capabilities, and the ability to regulate one’s behavior (i.e., risk taking) all help predict the onset and progression of tobacco use among young people. In addition to these cognitive processes, implicit attitudes (e.g., liking smoking or being willing to date a tobacco user) are also related to tobacco use among youth (HHS, 2012). Behavioral factors such as poor academic performance are also correlates of initiation and continued tobacco use by youth. Differences in tobacco use behaviors among youths with different levels of academic success persist and grow as the youths move from adolescence into young adulthood, so that by the time they reach young adulthood, the prevalence of tobacco use among non-college-going youth is twice that among those attending college (HHS, 2012).

Many researchers and public health experts believe that one of the most important factors affecting youth tobacco use is social influence, which occur at the interpersonal level (HHS, 2012). Peer influences are especially salient and strong. For example, young people often overestimate the prevalence of tobacco use among their peers (i.e., people of the same age), which is particularly important because perceptions that one’s peers use tobacco consistently predict an individual’s tobacco use. Both selection (i.e., choosing new friends who use tobacco) and socialization (i.e., being influenced by existing friends who use tobacco) are relevant to the movement between stages of tobacco use described earlier (HHS, 2012). Furthermore, research shows that tobacco use behaviors among and within these peer networks are influenced by group-level norms (e.g., school norms) and attempts to be liked by others in the group (HHS, 2012). As cigarette smoking has become less normative in the United States, recent research suggests that youth who self-identify as belonging to deviant peer groups are most likely to be smokers (HHS, 2012).

At the interpersonal level, family influences on youth tobacco use behavior can also be strong. The research on parental influence, including parental disapproval of tobacco use, parent tobacco use behaviors, and parenting practices (e.g., monitoring a child’s tobacco use, even as a young adult) suggests that these factors often moderate the influence of other factors, such as peer influence (HHS, 2012). The use of tobacco products among older siblings is also a predictive factor in youth tobacco use (HHS, 2012).

The intrapersonal and interpersonal factors listed above all interact in a complex web that can vary among individuals. These factors have stronger, more direct, and more immediate effects on youth tobacco use than other macro-level factors such as school climate and community norms about

tobacco use (HHS, 2012). However, macro-level factors must not be discounted, as they are the context in which these influences take shape. This context, in turn, is influenced by macro-level interventions, such as various tobacco policies (e.g., increased taxes on tobacco products) and communication campaigns (e.g., social marketing).

Smoking Cessation

Smoking cessation, like smoking initiation, is conceptualized as a multistep process. To succeed in stopping tobacco use, an individual must first decide to make an attempt to quit and then succeed in that attempt. Most individual quit attempts, even those made using the most effective contemporary treatments, do not succeed (Hatsukami et al., 2008). Instead, the tobacco user relapses (that is, returns to smoking), most often within the first week (Hughes et al., 2004). After 3 months, the likelihood of resuming tobacco use decreases, and a quit attempt that lasts for 6 or 12 months is generally considered to represent long-term successful cessation of tobacco use (HHS, 2010). However, many tobacco smokers return to smoking even after 12 months of abstinence (HHS, 2010). This multistep process is considered to be influenced primarily by internal factors, both biological and psychosocial, although interpersonal and macro factors such as social support are also important.

At the intrapersonal level, biological factors, specifically physiologic dependence on nicotine, influence an individual’s ability to succeed at quitting smoking. Nicotine is the major chemical component of tobacco smoke responsible for causing physiologic dependence on cigarettes. An individual’s risk of nicotine addiction depends on the dose of nicotine delivered and the way it is delivered (HHS, 2010). There is also evidence that some people are more predisposed to becoming addicted because of psychological or genetic factors or both (HHS, 2012). When an individual inhales cigarette smoke, nicotine is rapidly delivered to the brain, binding to nicotinic cholinergic receptors and activating the release of dopamine and other neurotransmitters that reinforce smoking and the behaviors associated with smoking (Benowitz, 2010). As an individual’s cigarette smoke exposure increases, the number of nicotine receptors increases, producing tolerance to higher doses of nicotine (Benowitz, 2008b; HHS, 2010). At that point, when nicotine levels decrease, an individual may experience withdrawal symptoms, including irritability, impatience, difficulty concentrating, an anxious or depressed mood, and an increased appetite. Smoking a cigarette alleviates these unpleasant symptoms. These symptoms begin within a few hours of smoking cessation, peak at 48 to 72 hours, and gradually diminish over weeks, although the duration and severity of nicotine withdrawal depend on the degree of nicotine addiction (HHS, 2010). This explains why

smokers often relapse (return to smoking) in the first hours and days after stopping smoking. To stop smoking, an addicted individual must manage and overcome the symptoms of nicotine withdrawal.

In addition to the addiction to nicotine, tobacco smoking is maintained by various behavioral factors, especially related habitual behaviors. For example, after repeated pairings of smoking with the end of a meal, a smoker comes to associate smoking with finishing a meal (HHS, 2010). Thereafter, finishing a meal triggers an urge to smoke. Additionally, smoking appears to increase an individual’s enjoyment of other reinforcers. For example, many individuals say that they crave cigarettes when drinking alcohol (HHS, 2010). It appears that nicotine has the effect of enhancing an individual’s pleasure from the other reinforcer (in this case, alcohol). The dual challenge of overcoming not only nicotine withdrawal symptoms but also learned behavioral associations with smoking causes many individual quit attempts to fail.

Various other factors, from intrapersonal to macro-level factors, can also influence the process of smoking cessation. For example, individuals may be motivated to stop smoking if they believe that the benefits of quitting outweigh the pleasures of continuing to smoke. The decision is a balance of the perceived threat of continuing to smoke and the beliefs of individuals that stopping smoking will benefit them. Another factor is a smokers’ confidence in his or her ability to succeed at quitting (i.e., self-efficacy). In many different treatment trials this has been shown to be an independent predictor of cessation success (Ockene et al., 2000). Finally, macro factors, such as social support from family and friends, cohabitation with smokers, and a tobacco user’s access or adherence to treatment can influence cessation through the intrapersonal and intrapersonal levels (TUDGP, 2008).

Finally, it is important to note that socio-demographic factors (e.g., age, gender/sex, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status) often moderate the impact of intrapersonal, interpersonal, and macro-level determinants described above and the speed with which individuals progress through these stages of tobacco use. One caveat is that the majority of empirical research to date has been specific to cigarette smoking, so that there is limited etiologic research available concerning the developmental processes and pathways of initiation for other tobacco products. Therefore, in modeling exercises one must understand that the factors important to the onset and progression of cigarette smoking for a white, affluent, 12-year-old girl may be very different from the factors important to the progression of cigar smoking for a 15-year-old African American boy. Both the factors themselves and the magnitude of the impact that the factors have on the onset, progression, and cessation of tobacco use among youth and young adults can be different.

WHY USE AGENT-BASED MODELS TO EXPLORE TOBACCO USE?

Existing models used in tobacco control have focused mostly on determining the long-term dynamics of population-level tobacco rates, either by extrapolating the status quo into the future or by projecting the consequences of policy interventions. For example, these models have been used to project changes in smoking prevalence and associated morbidity and mortality in the U.S. population over the next few decades, assuming that initiation and cessation rates remain fixed at current levels (HHS, 2014b). Those figures have then been contrasted with the morbidity and mortality implied by the same models when initiation and cessation rates are affected by various policy interventions, using what is known from past experience concerning how such interventions have affected the initiation and cessation rates.

These analyses have employed almost exclusively aggregate compartmental/system dynamics models, which assume a large degree of homogeneity among the population. In other words, these models assume that members of the population can be classified according to a limited number of distinguishing characteristics (for example, never, current, or former smokers) and that within each group in that classification the individuals behave identically. Additionally, the majority of these models do not consider social interactions among members of the population, and when they do, they assume that individuals within their unique groups are perfectly mixed and thus have the same chance of interacting with each other.

In general, this work has also treated certain important smoking processes as exogenous to the models (that is, as coming from outside a model and thus unexplained by the model). Tobacco use initiation, cessation, and relapse have been specified as externally supplied probabilities (that is, probabilities that are not explained by the model) that affect individuals at certain periods of their lives. Although these models do allow for policy interventions to affect the various probabilities, the models provide no details about the underlying mechanisms that generate such chances and their potential feedback relationship with the tobacco use rates they generate.

These aggregate population models have been very useful in determining the overall magnitude of the tobacco epidemic and its likely trajectory; however, given the increased complexity of the tobacco use landscape, it is becoming evident that policy makers need to better understand and model explicitly the essential social- and individual-level processes of tobacco use behavior (e.g., the mechanisms of initiation, cessation, and relapse) in order to anticipate as accurately as possible the effects of policy interventions. There is evidence that processes such as tobacco use initiation, cessation, and relapse are at least partially driven by social interactions. For example, the presence and strength of connection to friends or parents who smoke

is likely to have an impact on a person’s decision to initiate the smoking behavior, particularly among youth and young adults (HHS, 2012). Factors related to social interactions also play a role in smoking among adults, although there is insufficient evidence to suggest that these factors are paramount as compared to smoking initiation among youth and young adults. Similarly, the process of quitting smoking is influenced by interactions with other individuals (Chandola et al., 2004; Herd et al., 2009; Hitchman et al., 2014; Hymowitz et al., 1997; Westmaas et al., 2010). There is also ample evidence that living with individuals who smoke is a strong predictor of relapse among those who have recently quit (Garvey et al., 1992; Mermelstein et al., 1986). (See Chapter 3 for an in-depth discussion on social interactions.)

Analysis of survey data can help researchers identify the nature and strength of these social determinants of smoking behavior at the individual level, but computational models in general—and ABMs specifically—are needed to estimate the total population effects of those individual interactions. (For a description of ABMs see Chapter 1 and Appendix A.) These models can account for individuals’ differences and the multiple ways in which such individuals are influenced and can influence each other in order to estimate the combined effect of the multiple processes that constitute tobacco use behavior. These models can also account for important feedback mechanisms that have been, for the most part, ignored by existing aggregate models. For example, if a peer effect on smoking initiation is considered, a decline in smoking rates among the population would translate into a decline in smoking initiation, producing a cascade effect that would drive down smoking prevalence faster than what has been anticipated by traditional models. Although it is not guaranteed that ABMs will answer all policy questions, they may be able to inform those policies with underlying behavioral questions more fully than other modeling methods. Specifically, they are likely to inform the development, implementation, and enforcement of policies that are intended to influence behaviors. It is important to note that ABMs that do not focus on individual tobacco use behavior may also be useful to FDA or other tobacco control policy scientists. Examples include models of how the development of new tobacco products disrupt existing industry and retailer practices or models of community-level policies at the point of sale that are designed to affect retailer behavior (e.g., advertising).

In sum, given the strong social component inherent in tobacco use onset, cessation, and relapse and the heterogeneity of the relevant social interactions, ABMs have the potential to be an essential tool in assessing the effects on policies to control tobacco. These models could clarify the net effects that enacted policies have on a complex social environment and potentially inform inputs for aggregate population models, which focus

on the long-term consequences of such policies. Additionally, ABMs that explicitly model critical processes of tobacco use, such as initiation, cessation, and relapse, could be used to help answer many larger policy-relevant questions faced by FDA. Specific questions in the tobacco control field that researchers might want to model include what is the public health impact of lowering the nicotine content of combustible cigarettes to non-addictive levels? What is the impact of banning flavorings in electronic cigarettes? What are the impacts of competing media or education campaigns on reducing tobacco use? All of these questions require an understanding of the underlying behavioral mechanisms involved in initiation and cessation, and answering them would require a specific model of those processes.

Within the modeling community, it is often said that models need to be motivated by a specific question to be effective (Bankes, 1993; Bruch and Atwell, 2013; CREM, 2009; Macal and North; NRC, 2007, 2014). This may often be the case, as illustrated above, but the processes or mechanisms underlying these questions—what happens in the black box between policy implementation and potential behavior change—often need to be the focal point of the model before the specific question is addressed.

Finding 2-1: The committee finds that for many tobacco control policy questions, several key underlying processes—initiation, cessation, and relapse, among others—drive overall rates of tobacco use and have a strong social interaction component. An agent-based model could be a useful tool to represent these processes.

In the case of tobacco, a useful path will be to develop models of these processes first and then to apply them to the specific policy question. This does not imply that all efforts should be put into a single model of social processes that would then be applied to many different questions. Rather, accurately representing the underlying process of initiation, cessation, and relapse is, in some cases, essential to the development of a model of tobacco use behavior. It is important to note that there are other features of tobacco control policy that are not directly related to initiation and cessation (e.g., tobacco companies responding to FDA regulatory changes in an attempt to undermine those changes), so the modeling decision to focus on a specific policy question versus initiation or cessation needs to discussed early in model conceptualization.

This section outlines the conditions in which an ABM could be useful to inform tobacco control policy. It is difficult to identify specific domains that all policy-relevant ABMs would need to incorporate. Given the large range of factors and agents in the tobacco regulatory environment (as illustrated in this chapter), ABMs developed by CTP or others will require consultation before development begins (and throughout the lifespan of the model)

with relevant stakeholders, subject-matter experts, end users (e.g., decision makers), and the modeler to decide what domains and ABM characteristics would be appropriate for the intended purpose of the model (see Chapter 4). Although this report does not identify specific attributes or domains a tobacco control ABM would require—as that would vary depending on the purpose of the ABM as each policy question involves different agents and levels of interaction—it offers advice on the conditions in which ABM could be appropriate, important data considerations, and an evaluation framework that CTP can use in their future development of ABMs.

The description of the tobacco environment provided in this chapter outlines the difficult, but necessary, task of using models for tobacco use. Given that the results of tobacco control models could be used to inform real-time decisions by policy makers, it is critical to ensure that the modeling methods used are suitable for the question at hand and that they provide results that are reliable. In the next chapter, the committee offers guidance on using individual-level models to aid policy decisions.

Abrams, D. B. 2014. Promise and peril of e-cigarettes: Can disruptive technology make cigarettes obsolete? JAMA 311(2):135–136.

Agaku, I. T., B. A. King, C. G. Husten, R. Bunnell, B. K. Ambrose, S. S. Hu, E. Holder-Hayes, H. R. Day, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2014. Tobacco product use among adults—United States, 2012–2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 63(25):542–547.

Alamar, B. C., and S. A. Glantz. 2004. The tobacco industry’s use of Wall Street analysts in shaping policy. Tobacco Control 13(3):223–227.

APSC (Australian Public Service Commission). 2007. Tackling wicked problems: A public policy perspective. Australian Government, Australian Public Service Commission. http://www.apsc.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/6386/wickedproblems.pdf (accessed April 1, 2015).

ATF (Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives). 2015. Alcohol & tobacco. https://www.atf.gov/content/alcohol-and-tobacco (accessed February 18, 2015).

Bandura, A. 1986. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Bankes, S. 1993. Exploratory modeling for policy analysis. Operations Research 41(3):435–449.

Bauld, L., K. Angus, and M. de Andrade. 2014. E-cigarette uptake and marketing: A report commissioned by Public Health England. Institute for Social Marketing, University of Stirling, UK Centre for Tobacco & Alcohol Studies, Public Health England.

Benowitz, N. L. 2008a. Clinical pharmacology of nicotine: Implications for understanding, preventing, and treating tobacco addiction. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 83(4):531–541.

———. 2008b. Neurobiology of nicotine addiction: Implications for smoking cessation treatment. The American Journal of Medicine 121(4 Suppl 1):S3–S10.

———. 2010. Nicotine addiction. The New England Journal of Medicine 362(24):2295–2303.

Bhatnagar, A., L. P. Whitsel, K. M. Ribisl, C. Bullen, F. Chaloupka, M. R. Piano, R. M. Robertson, T. McAuley, D. Goff, N. Benowitz, American Heart Association Advocacy Coordinating Committee, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. 2014. Electronic cigarettes: A policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 130(16):1418–1436.

Blosnich, J., J. G. Lee, and K. Horn. 2013. A systematic review of the aetiology of tobacco disparities for sexual minorities. Tobacco Control 22(2):66–73.

Bruch, E., and J. Atwell. 2013. Agent-based models in empirical social research. Sociological Methods & Research 1–36.

Cawley, J., and C. Ruhm. 2011. The economics of risky health behaviors. In Handbook of health economics. Vol. 2. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. Pp. 95–199.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2014a. Best practices for comprehensive tobacco control programs. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health.

———. 2014b. Smoking and tobacco use: About this office. http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/ about (accessed February 19, 2015).

Chaloupka, F. J. 1991. Rational addictive behavior and cigarette smoking. Journal of Political Economy 99(4):722–742.

Chaloupka, F. J., and K. E. Warner. 2000. The economics of smoking. In Handbook of health economics edition 1. Vol. 1, edited by A. J. Culyer and J. P. Newhouse. Amsterdam, Netherlands: North Holland, Elsevier. Pp. 1539–1627.

Chandola, T., J. Head, and M. Bartley. 2004. Socio-demographic predictors of quitting smoking: How important are household factors? Addiction 99(6):770–777.

CREM (Council for Regulatory Environmental Modeling). 2009. Guidance on the development, evaluation, and application of environmental models. Washington, DC: Office of the Science Advisor, Council for Regulatory Environmental Modeling, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Crosse, M. 2014. Tobacco products: FDA spending and new product review time frames (GAO-14-508T). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Accountability Office. http://www.gao.gov/assets/670/662360.pdf (accessed April 1, 2015).

Dilley, J. A., C. Spigner, M. J. Boysun, C. W. Dent, and B. A. Pizacani. 2008. Does tobacco industry marketing excessively impact lesbian, gay and bisexual communities? Tobacco Control 17(6):385–390.

Dorfman, L., and L. Wallack. 1993. Advertising health: The case for counter-ads. Public Health Reports 108(6):716–726.

Fairchild, A. L., R. Bayer, and J. Colgrove. 2014. The renormalization of smoking? E-cigarettes and the tobacco “endgame.” New England Journal of Medicine 370(4):293–295.

Fallin, A., A. Goodin, Y. O. Lee, and K. Bennett. 2014. Smoking characteristics among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults. Preventive Medicine 73:123–130.

FDA (U.S. Food and Drug Administration). 2009. Tobacco product fees. http://www.fda.gov/ForIndustry/UserFees/TobaccoProductFees/default.htm (accessed January 22, 2015).

———. 2010. Enforcement action plan for promotion and advertising restriction. http://www.fda.gov/TobaccoProducts/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/ucm271744.htm (accessed February 25, 2015).

———. 2014. Overview of the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/TobaccoProducts/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/UCM336940.pdf (accessed January 22, 2015).

———. 2015a. The real cost: Overview. http://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/CentersOffices/OfficeofMedicalProductsandTobacco/AbouttheCenterforTobaccoProducts/PublicEducationCampaigns/TheRealCostCampaign/ucm388656.htm (accessed February 25, 2015).

———. 2015b. Tobacco product marketing orders. http://www.fda.gov/TobaccoProducts/Labeling/MarketingandAdvertising/ucm339928.htm (accessed January 22, 2015).

Fu, S. S., D. Burgess, M. van Ryn, D. K. Hatsukami, J. Solomon, and A. M. Joseph. 2007. Views on smoking cessation methods in ethnic minority communities: A qualitative investigation. Preventive Medicine 44(3):235–240.

Garvey, A. J., R. E. Bliss, J. L. Hitchcock, J. W. Heinold, and B. Rosner. 1992. Predictors of smoking relapse among self-quitters: A report from the normative aging study. Addictive Behaviors 17(4):367–377.

Gfroerer, J., S. R. Dube, B. A. King, B. E. Garrett, S. Babb, and T. McAfee. 2013. Vital signs: Current cigarette smoking among adults aged greater than or equal to 18 years with mental illness—United States 2009–2011. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 62(5):81–87.

Glanz, K., B. K. Rimer, and NCI. 2005. Theory at a glance: A guide for health promotion practice. 2nd ed. NIH Publication No. 05-3896. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute.

Grana, R., N. Benowitz, and S. A. Glantz. 2014. E-cigarettes: A scientific review. Circulation 129(19):1972–1986.

Hajek, P. 2013. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation. Lancet 382(9905):1614–1616.

Hamburg, M. A. 2014. FDA public education campaign aims to prevent and reduce youth tobacco use. http://blogs.fda.gov/fdavoice/index.php/2014/02/fda-public-educationcampaign-aims-to-prevent-and-reduce-youth-tobacco-use (accessed November 13, 2014).

Hatsukami, D. K., L. F. Stead, and P. C. Gupta. 2008. Tobacco addiction. Lancet 371(9629): 2027–2038.

Hatzenbuehler, M. L., N. F. Wieringa, and K. M. Keyes. 2011. Community-level determinants of tobacco use disparities in lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth: Results from a population-based study. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine 165(6):527–532.

Hayden, J. 2014. Chapter 4: Health belief model. In Introduction to health behavior theory. 2nd ed. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Henchman, J., and S. Drenkard. 2014. Cigarette taxes and cigarette smuggling by state. Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact. http://taxfoundation.org/sites/taxfoundation.org/files/docs/FF421.pdf (accessed November 13, 2014).

Herd, N., R. Borland, and A. Hyland. 2009. Predictors of smoking relapse by duration of abstinence: Findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) four country survey. Addiction 104(12):2088–2099.

HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 2010. How tobacco smoke causes disease: The biology and behavioral basis for smoking-attributable disease: A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention, Office on Smoking and Health.

———. 2012. Preventing tobacco use among youth and young adults: A report of the Surgeon General Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health.

———. 2014a. 21 CFR parts 1100, 1140, 1143 proposed rule. Federal Register 79(80):23142–23207.

———. 2014b. The health consequences of smoking—50 years of progress: A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health.

Hitchman, S. C., G. T. Fong, M. P. Zanna, J. F. Thrasher, and F. L. Laux. 2014. The relation between number of smoking friends, and quit intentions, attempts, and success: Findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) four country survey. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 28(4):1144–1152.

Hochbaum, G. M. 1958. Public participation in medical screening programs; a sociopsychological study. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service, Bureau of State Services, Division of Special Health Services, Tuberculosis Program.

Hughes, J. R., J. Keely, and S. Naud. 2004. Shape of the relapse curve and long-term abstinence among untreated smokers. Addiction 99(1):29–38.

Hyland, A., C. Higbee, Q. Li, J. E. Bauer, G. A. Giovino, T. Alford, and K. M. Cummings. 2005. Access to low-taxed cigarettes deters smoking cessation attempts. American Journal of Public Health 95(6):994–995.

Hymowitz, N., K. M. Cummings, A. Hyland, W. R. Lynn, T. F. Pechacek, and T. D. Hartwell. 1997. Predictors of smoking cessation in a cohort of adult smokers followed for five years. Tobacco Control 6(Suppl 2):S57–S62.

Jamal, A., I. T. Agaku, E. O’Connor, B. A. King, J. B. Kenemer, and L. Neff. 2014. Current cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2005–2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 63(47):1108–1112.

King, B. A., S. R. Dube, and M. A. Tynan. 2012. Current tobacco use among adults in the United States: Findings from the National Adult Tobacco Survey. American Journal of Public Health 102(11):e93–e100.

Kirkwood, C. 1998. Chapter 1: System behavior and causal loop diagrams. In System dynamics methods: A quick introduction. http://www.nutritionmodels.com/copyrighted_papers/Kirkwood1998.pdf (accessed March 18, 2015).

Kolko, J. 2012. Wicked problems: Problems worth solving: A handbook and a call to action. Austin, TX: Austin Center for Design. https://www.wickedproblems.com/1_wicked_problems.php (accessed March 18, 2015).

Kurti, M. K., K. von Lampe, and D. E. Thompkins. 2012. The illegal cigarette market in a socioeconomically deprived inner-city area: The case of the South Bronx. Tobacco Control 22(2):138–140.

Lasser, K., J. W. Boyd, S. Woolhandler, D. U. Himmelstein, D. McCormick, and D. H. Bor. 2000. Smoking and mental illness: A population-based prevalence study. JAMA 284(20):2606–2610.

Lee, J. G., G. K. Griffin, and C. L. Melvin. 2009. Tobacco use among sexual minorities in the USA, 1987 to May 2007: A systematic review. Tobacco Control 18(4):275–282.

Lee, J. G., C. B. Agnew-Brune, J. A. Clapp, and J. R. Blosnich. 2013. Out smoking on the big screen: Tobacco use in LGBT movies, 2000–2011. Tobacco Control 23(e2):e156–e158.

Leischow, S. J., D. A. Luke, N. Mueller, J. K. Harris, P. Ponder, S. Marcus, and P. I. Clark. 2010. Mapping U.S. Government tobacco control leadership: Networked for success? Nicotine & Tobacco Research 12(9):888–894.

Luke, D. 2013. Systems science and tobacco control. Presentation at 13th annual American Academy of Health Behavior Scientific Meeting, March 17-20, 2013, Santa Fe, NM. http://aahb.wildapricot.org/Resources/Documents/Luke%20AAHB%202013%20Tobacco%20Control%20_%20Systems.pdf (accessed December 12, 2013).

Macal, C. M., and M. J. North. 2010. Tutorial on agent-based modelling and simulation. Journal of Simulation 4(3):151–162.

Malarcher, A., S. R. Dube, L. Shaw, S. Babb, and R. Kaufmann. 2011. Quitting smoking among adults —United States, 2001–2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 60(44):1513–1519.

Mayhew, K. P., B. R. Flay, and J. A. Mott. 2000. Stages in the development of adolescent smoking. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 59(Suppl 1):S61–S81.

McLeroy, K. R., D. Bibeau, A. Steckler, and K. Glanz. 1988. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education Quarterly 15(4):351–377.

Mermelstein, R., S. Cohen, E. Lichtenstein, J. S. Baer, and T. Kamarck. 1986. Social support and smoking cessation and maintenance. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 54(4):447–453.

Miner, C. 2012. Information technology, tools, tobacco products, and public health. http://blogs.fda.gov/fdavoice/index.php/2012/08/information-technology-tools-tobaccoproducts-and-public-health (accessed February 15, 2015).

Morley, C. P., K. M. Cummings, A. Hyland, G. A. Giovino, and J. K. Horan. 2002. Tobacco institute lobbying at the state and local levels of government in the 1990s. Tobacco Control 11(Suppl 1):i102–i109.

NAAG (National Association of Attorneys General). 1998. Master settlement agreement between 46 state attorneys general and participating tobacco manufacturers. http://www.naag.org/assets/redesign/files/msa-tobacco/MSA.pdf (accessed April 2, 2015).

NACS (The Association for Convenience & Fuel Retailing). 2014. House subcommittee examines implementation of Tobacco Control Act. http://www.nacsonline.com/news/daily/pages/nd0409142.aspx#.VGEsk_nF_OH (accessed November 10, 2014).

NCAI (National Congress of American Indians). 2015. Examples of Tribal Tax Codes, Tax Agreements & Other Resources. http://www.ncai.org/initiatives/partnerships-initiatives/ncai-tax-initiative/examples-of-tribal-tax-codes-tax-agreements-other-resources (accessed March 2, 2015).

NCI (National Cancer Institute). 2007. Greater than the sum: Systems thinking in tobacco control. Tobacco Control Monograph No. 18. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute.

NRC (National Research Council). 2007. Models in environmental regulatory decision making. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

———. 2014. Advancing land change modeling: Opportunities and research requirements. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

———. 2015. Understanding the U.S. illicit tobacco market: Characteristics, policy context, and lessons from international experiences. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Ockene, J. K., K. M. Emmons, R. J. Mermelstein, K. A. Perkins, D. S. Bonollo, C. C. Voorhees, and J. F. Hollis. 2000. Relapse and maintenance issues for smoking cessation. Health Psychology 19(1 Suppl):17–31.

OFR (Office of the Federal Register). 2014. A guide to the rulemaking process. https://www.federalregister.gov/uploads/2011/01/the_rulemaking_process.pdf (accessed November 21, 2014).

Plsek, P. E., and T. Greenhalgh. 2001. The challenge of complexity in health care. BMJ 323(7313):625–628.

Pokhrel, K., and J. Caine. 2012. Tobacco control in LGBT communities. Washington, DC: Legacy.

Prochaska, J. O., C. A. Redding, and K. E. Evers. 2008. The transtheoretical model and stages of change. In Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice, 4th ed, edited by K. Glanz, B. K. Rimer, and K. Viswanath. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. Pp. 97–122.

Rittel, H. W., and M. M. Webber. 1973. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences 4(2):155–169.

Sallis, J. F., N. Owen, and E. B. Fisher. 2008. Ecological models of health behavior. In Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice. 4th ed, edited by K. Glanz, B. K. Rimer, and K. Viswanath. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. Pp. 465–486.

Samuel, K. A., K. M. Ribisl, and R. S. Williams. 2012. Internet cigarette sales and Native American sovereignty: Political and public health contexts. Journal of Public Health Policy 33(2):173–187.