4

Approaches to Informed Consent

In the workshop’s third session, two panelists addressed new approaches to creating a meaningful informed consent process. Rebecca Sudore, a practicing geriatrician and hospital and palliative care physician at the San Francisco VA Medical Center and associate professor at the University of California, San Francisco, discussed the important role that conversation can play in creating a meaningful informed consent process. Christopher Trudeau, associate professor at the Thomas M. Cooley Law School, spoke about how to redesign consent forms so that they are understandable and meet the requirements of federal and state regulations. An open discussion followed the two presentations.

THE IMPORTANCE OF THE INFORMED CONSENT CONVERSATION IN ADDITION TO THE FORM1

Rebecca Sudore

University of California, San Francisco

For Sudore, advance directives represent the ultimate informed consent. Informed medical decision making, that may have life-and-death consequences, should be occurring when patients are completing advanced

_____________

1 This section is based on the presentation by Rebecca Sudore, a practicing geriatrician and hospital and palliative care physician at the San Francisco VA Medical Center and associate professor at the University of California, San Francisco, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the IOM.

directives, physicians are discussing Physician’s Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatments (POLST forms), and do-not-resuscitate orders. In these instances, as with informed consent under other circumstances, people are often confused by the content of the forms and the many legal terms associated with advanced directive types of forms. Often, patients or their surrogates sign forms with answers to questions regarding resuscitation, machine-assisted breathing, and other life-sustaining treatments that conflict with prior advance directive forms and the patient’s true wishes.

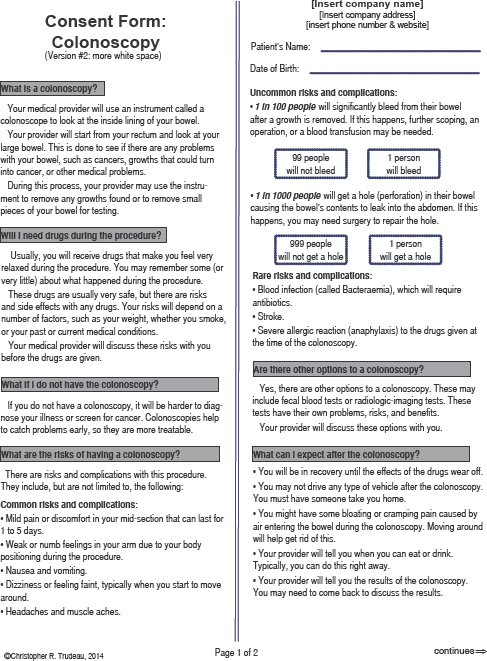

Over the past decade, Sudore has worked with roundtable member Michael Villaire to create advanced directive forms that are easy to understand. These forms, she said, are written at a fifth-grade reading level, use pictures to help explain complicated concepts and terms, and are available in Chinese, English, Farsi, Russian, Spanish, Tagalog, and Vietnamese (see Figure 4-1). A randomized controlled trial showed that people preferred this form overwhelmingly and that it doubled 6-month completion rates (Sudore et al., 2007). Sudore and her colleagues did find, however, that uncertainty still exists regarding hypothetical scenarios that are used to portray what could happen in the future, whether those were used for informed consent or advance directives. For example, 50 percent of a diverse population of older adults who reported a life-sustaining treatment preference on the basis of a hypothetical scenario were uncertain about their decision (Sudore et al., 2010). She noted that she and other investigators have shown that uncertainty is often associated with limited literacy, lower education, minority status, and poor health status (Allen et al., 2008; Volandes et al., 2010).

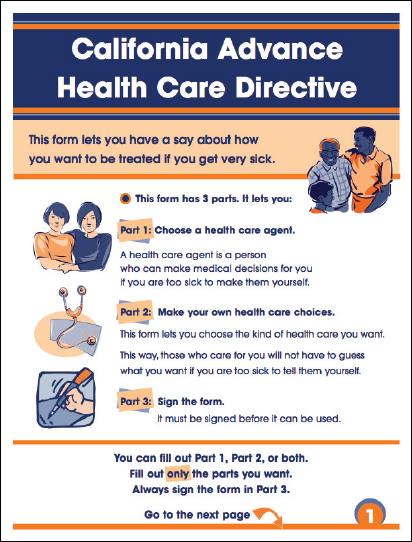

One lesson to draw from these studies with regard to informed consent conversations, said Sudore, is that “just because somebody makes a choice, it does not mean that they fully understand the meaning and the ramifications of that choice.” As an example, she showed a portion of a POLST form used to direct a physician regarding life-sustaining treatment (see Figure 4-2). Section A of the form asks patients if they want cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in the event that they do not have a pulse. Section B is about medical interventions and asks patients if they want (a) comfort measures only, (b) limited additional interventions including comfort care, medical treatment, antibiotics, intravenous fluids, and noninvasive positive airway pressure but not intubation, or (c) full treatment. When she asked one of her patients what it meant to check the “limited additional interventions” box, the patient’s response was, “I only want to be on machines for a few days. My family knows this.” This is not, however, what a physician would do, said Sudore.

Sudore’s patient was not alone in being confused by these options. Unpublished pilot study data from her colleague Susan Hickman show that only 55 percent of people understand what is on a POLST form. Moreover,

FIGURE 4-1 First page of the California’s advance health care directive.

SOURCE: Institute for Healthcare Advancement, 2014.

59 percent of the time, the answers on this form are not in agreement with what the patients’ actual goals when asked in the moment. Other investigators have found similarly confused patient responses to the questions on advance directive forms (Hammes et al., 2010; Heyland et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2009). According to a study by Heyland and colleagues, 70 percent of documented end-of-life wishes in the hospital do not reflect what patients say they want for themselves at that moment in time.

However, studies that focused on discussions and not just on forms show different results, said Sudore (Detering et al., 2010; Kirchhoff et al.,

FIGURE 4-2 Medical intervention form offering patients three choices for care.

SOURCE: Sudore, 2014.

2010). She noted that work done by a group called Respecting Choices, which works with trained facilitators to conduct in-depth conversations with patients, produced documented end-of-life wishes accurately representing patient desires approximately 90 percent of the time. These discussion-centered methods also increased patient understanding and satisfaction and helped surrogates know what patients want. These discussions also decreased cost and increased the quality of care. The lesson from these studies, said Sudore, is that discussions are needed to confirm understanding.

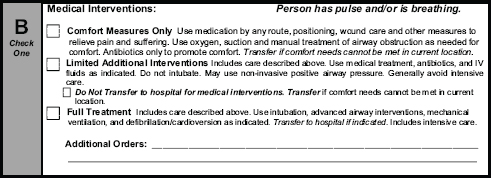

Sudore then spoke about the work that she and her colleagues have done to modify the consent process. The study she described was nested in a study of the advance directive trial she had already noted. It involved providing test subjects with a consent form written at the sixth-grade reading level and reading it to them verbatim in either English or Spanish. The researchers then assessed the patients’ knowledge with seven true/false questions about the content of the consent form and followed that assessment with a teach-to-goal process that used repeated, targeted education until the patients achieved comprehension (Sudore et al., 2006). Through the first pass of the program, only 28 percent of the people were able to answer correctly all of the knowledge questions. Some 52 percent needed a second pass, and 20 percent needed a third pass. All of the non-native English speakers required more than one pass. “We found that as the literacy score decreased, the odds of requiring more passes increased,” said Sudore (see Figure 4-3). The good news from this study was that all study participants were able to understand the information presented within three passes.

Limited health literacy is surmountable, Sudore said. She cited a study on hospitalized patients with asthma as an example (Paasche-Orlow et al., 2005). In this study, mastery of an inhaler was achieved in 100 percent of the patients after three passes through the instructions. In addition, a

FIGURE 4-3 Results of assessment indicating that as literacy score decreased, the odds of requiring more passes increased.

SOURCE: Sudore et al., 2006.

study of surgical intensive care patients found that repeat or teach-back techniques improved informed consent comprehension from 53 percent of the patients to 70 percent, and the improvement was particularly notable with regard to understanding risks and alternatives (Fink et al., 2010). The investigators found that this repeat-back process took a mere 2.6 minutes longer than the regular informed consent process. The lessons for informed consent, said Sudore, are that an interactive teach-to-goal techniques may be necessary and that literacy and language do need to be addressed.

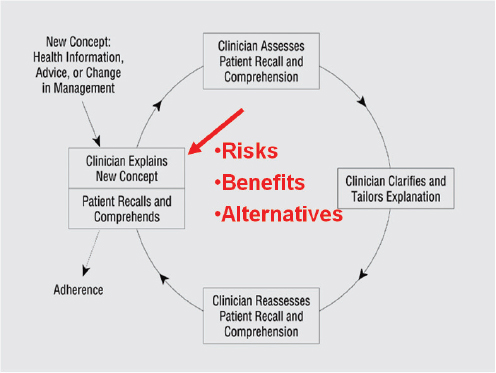

Sudore explained that the basic teach-back or teach-to-goal process starts with a new concept or new piece of health information and then uses an iterative process to achieve and assess understanding (see Figure 4-4). The problem with this approach, said Sudore, is that it gives patients information on risks, benefits, and alternatives before it addresses the patient’s concerns. “What matters most to patients is not the treatment, but the outcome of the treatment,” said Sudore. As an analogy, she said the current process is like putting the cart before the horse. “It is not intubation, CPR,

FIGURE 4-4 The teach-back or teach-to-goal process.

SOURCE: Schillinger et al., 2003.

surgery, blood transfusion, or chemotherapy, which I call the cart, but how their life will be after treatment, which I am calling the horse,” she said. As one patient from a focus group said, “If I go through all of this, how weak will I be? Will I be able to get myself up out of bed and take a bath, you know, or what will happen to me?”

To make this point, Sudore presented another example from one of her surgery colleagues (Schwarze et al., 2013). As described in Schwarze and colleagues’ publication, “a 77-year-old frail woman came into the emergency room with a large abdominal aneurysm. Though she had previously declined elective surgery on multiple occasions, she now agreed to have surgery, given that the main risk of not having surgery was death. After eight hours of surgery and admittance to the intensive care unit, the patient went into cardiac arrest and was brought back to the operating room to have her bleeding controlled. After another six hours of surgery and 45 units of blood stabilized her, the patient was brought back to the intensive care unit without the need for blood pressure support.” Sudore said the

surgeons were happy because they believed that this was the best outcome they could expect for this frail older person. The woman’s family, however, was horrified because the extra life-support treatments went against the woman’s values and wishes—for years, the woman had voiced fears about the use of life support and spending her remaining life in a nursing home.

Revisiting the concept of using best-case and worst-case scenarios that Schenker had described in the previous panel session to get at this patient’s values and wishes, Sudore said that a better approach than using risks, benefits, and teach-back might be to first understand what is the most important outcome to the patient and then describe all the options in terms of best-case and worst-case expected outcomes (Schwarze et al., 2013). This allows a range of options the patient can choose from that is focused on the outcome of treatment and what their life may look like after a particular treatment path. The best-case outcome for surgery in this example would be a 6- to 10-hour operation followed by 5 to 7 days of intensive care with a breathing tube and maybe dialysis, 2 to 3 weeks in the hospital, and then transition to a nursing home. After the surgery, it is unlikely that the patient would be able to return to living independently and would likely require living the rest of her life in a nursing home or with palliative care. The best-case outcome of palliative care would be that the patient would be admitted to the hospital’s palliative care service, which would provide enough pain medication to stop the pain in her chest and enable the woman’s family to be with her at her bedside during what would likely be another 24 to 48 hours before death. It might even be possible for the patient to go home, with hospice care providing pain relief. The lesson from this and other similar examples, said Sudore, is that “the first thing we need to do is elicit patients’ values and then describe the outcome of treatment in real-life terms that the patient can understand.” The use of stories can be helpful for understanding, she added.

Sudore noted that back when Terri Schiavo’s story was in the news, she and her colleagues found that 92 percent of both English and Spanish speakers—including those who were illiterate and could not read in either language—were familiar with Schiavo and the media coverage of her case and that as a result, 70 percent of those people had clarified their own goals for medical care, and more than 60 percent had been motivated to discuss their wishes with their family and wanted to complete advance directive forms (Sudore, 2008). In addition to stories in the news, video images help improve understanding, increase engagement, decrease decisional conflict, and help people identify their own goals, Sudore added.

Geriatric patients have their own issues, including clinician bias that assumes that older patients have dementia. “People often automatically assume that older adults are demented, delirious, and cannot make their own decisions. Clinicians often defer to caregivers, when they haven’t done

the work to find out if a patient has decision-making capacity,” said Sudore. Other issues result from chronic illness and neurocognitive processing deficits, both from disease and medication, that can cause cognitive slowing. However, this does not automatically mean that these patients cannot process information. It may be necessary to speak more slowly when going over informed consent documents or discussing end-of-life issues.

In addition, 63 percent of adults over age 70 and 80 percent of people over age 85 have hearing loss, particularly with respect to high-frequency hearing that helps make consonants distinct and understandable. Unfortunately, Sudore added, speaking more loudly does not help, and often patients misinterpret information as a result (Bainbridge, 2014). Many patients also lose their hearing aids during a hospitalization, making them vulnerable to poor understanding. The use of a small portable amplification device can be a lifesaver, and Sudore recommended that everyone who works in a hospital have one. “We will go into the ICU, and people will say that this person does not understand, and they think the patient is delirious. We put a pocket talker on them and have a completely lucid conversation,” she said.

She also noted that patients often lose their glasses while in the hospital, which can create communication difficulties because many patients accommodate their hearing loss by lip reading. In fact, it is important to always face patients when speaking to them, she said—often, health care providers are working on a computer while talking to their patients, making it hard for patients to both hear and see. She also recommended decreasing background noise by putting each patient’s back to the wall, sitting as close as possible to the patient, and using all forms of hearing amplification, including hearing aids and portable amplification devices. Sudore recounted the story of a patient in the intensive care unit who had a tracheotomy tube and could not communicate. Having the respiratory therapist insert a Passy-Muir valve enabled the patient to speak and have a meaningful conversation about her care.

In the case of patients with dementia, teach-back may not work, but the possibility exists that it could, because even people with cognitive impairments can make informed medical decisions. When they cannot, caregivers are the alternative for consent, but caregivers do not always have high health literacy. One study found that 36 percent of paid caregivers for the elderly had low health literacy (Lindquist et al., 2011).

In summary, Sudore listed six lessons that she hoped the workshop participants would take from her presentation:

- An interactive teach-to-goal process may be necessary.

- Literacy and language need to be addressed.

- Patients’ values need to be elicited first, and then the outcome of the treatment needs to be described in real-life terms.

- Visual images and stories are powerful teaching tools.

- Hearing and all forms of communication should be maximized.

- Health care providers need to be aware of age/dementia bias and caregiver literacy.

ESTABLISHING HARMONY BETWEEN THE RULES AND HEALTH LITERACY2

Christopher Trudeau

Thomas M. Cooley Law School

“How can we create a form that complies with the law and promotes a conversation?” asked Christopher Trudeau at the start of his presentation. That is the question he is attempting to answer in his work, specifically with regard to the design of informed consent forms for medical procedures as opposed to those for clinical trials. He noted that the former are easier than the latter because there are fewer rules and regulations at the federal level and because most state-enacted regulations are based on the common law principles that Jeremy Sugarman talked about in the workshop’s first presentation.

While every state has slightly different requirements, the informed consent document must always describe the risks and alternatives, contain a description of the procedure, and provide a place for the patient to give consent to treatment; it might also contain a few other legal disclosures that depend on the state and provider’s needs, Trudeau said. These are the basic limitations, but they do not mandate the specific language or words that have to be used to fulfill these regulations, though most legal counsel that Trudeau speaks with believe that the regulations do mandate specific language. “That is not true. These topics need to be covered, but the language that we use is usually not covered by law,” said Trudeau. What the consent form language does have to satisfy is one of two standards: the professional customs standard, used by 23 states, and the reasonable patient standard, required by 24 states and the District of Columbia. Tennessee uses an international tort standard, and the other two states use a hybrid of the professional and patient standards. The professional customs standard refers to what the prevailing practicing physician knows in a specific locality or community. The reasonable patient standard refers to what a reasonable

_____________

2 This section is based on the presentation by Christopher Trudeau, associate professor at the Thomas M. Cooley Law School, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the IOM.

patient would understand, which, as Trudeau pointed out, is not the same thing as what is reasonable to a judge or lawyer.

He also noted that when laws and regulations concerning informed consent for treatment were first being promulgated at the turn of the 20th century, there was no knowledge base about health literacy. That type of information about what patients understand is only 15 to 20 years old, he explained. So how, asked Trudeau, does health literacy fit within the legal standards? “It doesn’t,” he said. In fact, his attempt to find cases where people have argued that a lack of health literacy and understanding should lower the standard has largely failed, being confined to three or four cases that deal with a patient not understanding a piece of information because the individual could not read.

Trudeau argued that, from an advocacy perspective, it may be necessary to threaten or pursue lawsuits to trigger changes in the consent form regulations that reflect the health literacy literature that has developed over the past two decades. If health literacy starts becoming the standard, and groups such as the IOM or the American Medical Association (AMA) start promoting that standard, it will provide lawyers who are suing over a lack of informed consent to better make the argument that standards must change. “Once we get one liable case, everybody starts to change their forms and get on board with us, which is really what we want,” said Trudeau.

Acknowledging that inducing change in this manner will take time, Trudeau said that some steps can be taken now to aid patient understanding for the simple fact that the law and health literacy are not mutually exclusive, even though lawyers sometimes think they are. “Frankly, that’s because most lawyers do not know what health literacy is,” he said, adding that advocacy can change that misperception.

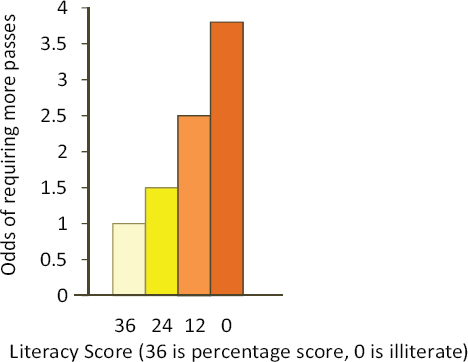

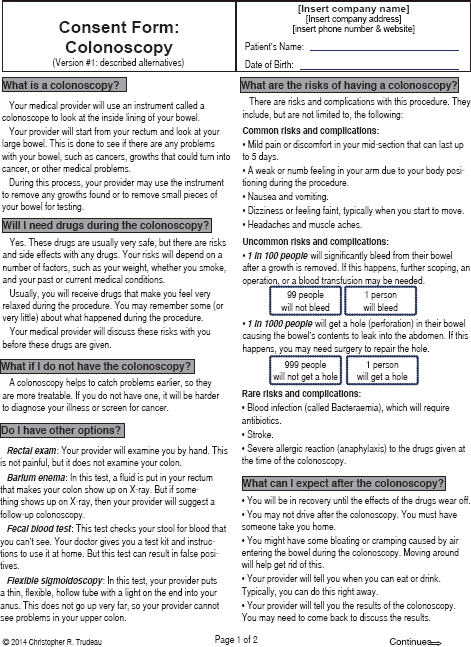

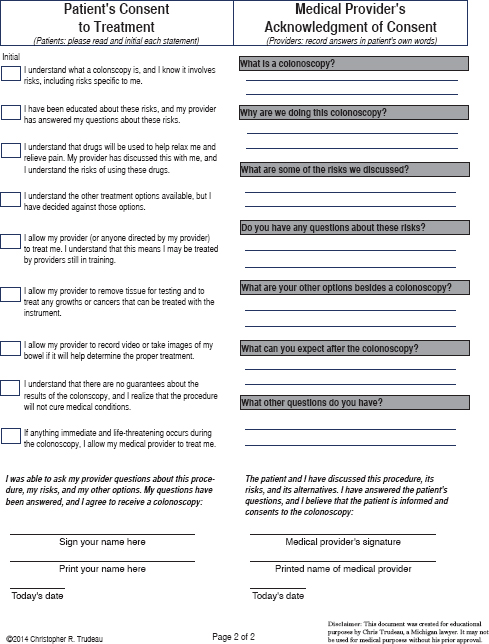

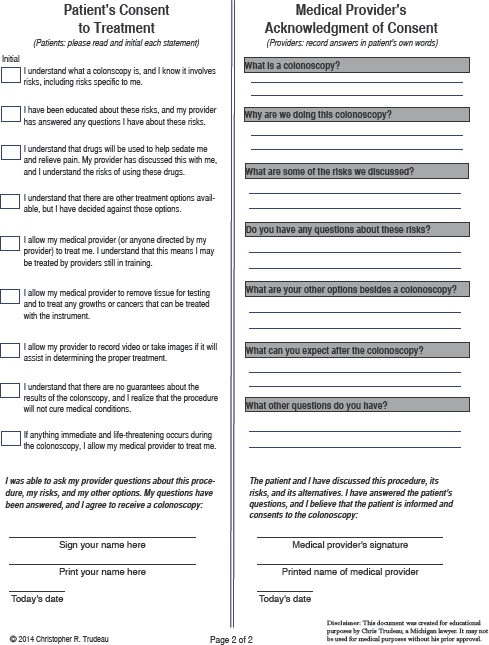

Trudeau’s efforts to redesign informed consent forms has focused on colonoscopy, a nonemergency procedure for which there is time in advance to procure informed consent. He showed three forms that he found in a random search and noted that all three were written at about an 11th-grade level. That two of the forms were similar, he suggested, makes it likely that one facility found a standard form and modified it to fit its particular needs as determined by a lawyer, and all three of the forms had many problems with the writing above and beyond the grade level at which they were written. He questioned, for example, whether it was necessary to use medical terms such as “coagulation,” “sedation,” or “digital optical instrument” or to create ambiguity using constructs such as “and/or,” by adding what seemed to be random “(s)” after some nouns but not others, or by being inconsistent in the use of the first-person singular or second person. He pointed out these flaws not just to show how unintelligible these forms could be but also to underscore that lawyers are not good at creating these

documents. “We are good at protecting our clients from liability,” said Trudeau. “We are not good at document design. We are not good at thinking about the impact of language on the patients and on others.”

One example that he thought was particularly egregious described what would happen during the colonoscopy if some abnormality was spotted. Instead of saying something such as “small growths can frequently be completely removed,” this document said, “If an abnormality is seen or suspected, a small portion of tissue may be removed for microscopic study or the lining may be brushed and washed with a solution that can be sent for analysis of abnormal cells, cytology,” none of which wording is required by law. His point in describing one flaw after another was to show that lawyers do not think about patient understanding and about drafting a clear form. They just draft a form that is going to comply with what they believe is mandated in a specific state’s regulations.

The first step in creating a form that complies with the principles that have been raised at this workshop is to understand where the form fits into the consent process, given that the form is just part of the consent process, Trudeau said. In the case of a colonoscopy, the process starts when a physician recommends to someone 50 years or older that he or she needs to get a colonoscopy. Ideally, Trudeau explained, there should be a conversation at this point with some initial information and some questions from the patient, and the patient should receive some educational materials or complete a tutorial that helps the person understand the procedure, the alternatives, and the risks. The patient then prepares for the exam, goes to the appointment, and then receives the consent form. Even though it is unlikely that the patient would back out at this point, having already prepped for the procedure, there should be time for further discussion and the opportunity for teach-back before the patient signs the consent form. Trudeau noted that, although his emphasis is on redesigning the form, there is also the need to redesign most of the educational materials on colonoscopy that patients receive.

Step two in the process, he said, is to create clear content that incorporates health literacy principles while also containing the necessary language that describes the technique and outlines the risks, alternatives, and other information germane to a particular treatment that federal and state regulations mandate. Step three is to consider a design strategy that limits the document in size—two pages maximum for a colonoscopy, said Trudeau—and that provides space for office administrative needs and signature lines, including lines for witnesses in states with that requirement. Trudeau noted that no regulations specify what a consent document must look like and that the design is subject to the discretion of each organization.

With these ideas in mind, and after reviewing the dozens of consent forms that he could find and the requirements of his state, he created a

couple of versions of a consent form for colonoscopy. The first version (see Figure 4-5) is one piece of paper, front and back, and makes liberal uses of subheads that pose the common questions that patients ask, but Trudeau said that this version appears too dense and has too much information. After thinking about how to create more white space so that the form is more inviting, he created a second version (see Figure 4-6), which uses simplified explanations of the basic concepts of colonoscopy on the assumption that the patient would have already received some information from the physician who recommended that the patient undergo this procedure. This second version, he said, tested at a 7.18 grade level and noted that the words “colonoscopy” and “colonoscope” are enough to increase the grade level. He also conceded that it might be possible to replace “bowels” with “colon” or “insides.”

To go along with this form, a physician could start the conversation, before handing out the form, by describing the procedure with language such as this: “This is what is going to happen. We are just going to go in the behind and look at your large bowel and see if there are any problems with your bowel such as cancer.” Trudeau pointed out that he did not have to use the word “polyp.” He noted, too, that in his state, only a physician, not a nurse practitioner or physician’s assistant, can start the consent process. The physician could explain the colonoscope with language such as “I may use this instrument to remove any growths that I find or to remove small pieces of your bowel for testing.”

Trudeau questioned whether his use of the word “risks” in a subhead was the best approach and wondered if describing the worst-case, best-case, and most likely scenarios might be more understandable by the average patient. If it was not possible to use that type of presentation on the consent form, he suggested that such information be included in education materials to accompany the consent form. He also wondered if his approach to quantifying risk was the best one—instead of stating the risk of bleeding at 1 in 100 or perforating the bowel at 1 in 1,000, the document explains that 99 people will not bleed and that one will and that 999 people will not have a hole in the bowel and that one will. “This is just a different way of conveying the same information that might have an impact on at least a wider array of people,” he explained.

The second side of both forms contains the consent boxes, signature lines, and teach-back area. It will be necessary, said Trudeau, to teach physicians how to conduct a teach-back using this form. He explained that if the provider is properly trained, the form and the discussion that goes with it at this point not only will help with patient understanding but should also make the lawyers happy by providing a record of the patient’s understanding in case of later litigation. In the end, said Trudeau, there are many design options that can increase readability and understandability, but they

will not by themselves do much good if the content is neglected and if the physician’s intent is to simply hand out the form and get the patient to sign it. “What I want you to understand is that we can cover our legal bases and use plain language and incorporate teach-back and probably produce more legal protection for all of our providers as well,” said Trudeau in closing his presentation. “Don’t let lawyers tell you it can’t be done. We can create this harmony.”

Cindy Brach opened the discussion by asking Trudeau why lawyers are not leading the charge to simplify forms and explain terms and concepts more clearly. To her, lawyers should be most concerned about liability concerns that would go along with having patients sign forms they do not understand. “How do we get them over that hump to realize, even if their only goal is to protect against lawsuits and malpractice that this is what they should be arguing for?” asked Brach. Trudeau blamed the lack of lawyer leadership on this issue to two factors. First, he said, lawyers need to know about and understand health literacy and the impact of poorly designed and complicated forms, and, second, they need the skills to draft these forms. Lawyers, he said, have little training in literacy principles, let alone those of health literacy—if they had, he stated, the Affordable Care Act would not be 2,200 pages long, and credit card agreements would not be written at a 12th-grade level.

Law schools share at least part of the responsibility for this lack of knowledge, he added, and noted that there is a significant body of research on what judges want to see in a legal brief, and in general they want documents that are clear and understandable. Nonetheless, he said, law schools spend little time instructing students in how to draft documents that are clear and understandable despite the efforts of what he called the plain language movement. He noted that he is part of several organizations that are working to inform lawyers about literacy factors, yet despite their efforts change is occurring slowly. What could move the field along more quickly is to use the stick of litigation over forms that are not understandable, given that lawyers are trained to be more concerned with what the courts say than with what the average person says.

Andrew Pleasant first commented that moving the informed consent moment to a time prior to the colonoscopy appointment would potentially save time and money if someone says no to consent, and it would reduce the pressure of deciding on consent when the procedure is about to take place. He also supported the idea of framing the consent document and discussion around outcomes, but he wondered if physicians are resistant to discussing outcomes because they tend to be hesitant about predicting

FIGURE 4-5 A colonoscopy consent form incorporating teach-back.

SOURCE: Trudeau, 2014.

outcomes and, in fact, are not trained to do so, given the potential liability problems that could come with predicting outcomes as opposed to merely describing procedures. Trudeau agreed with Pleasant about giving patients the consent form earlier in the process, perhaps with the education forms, but he wondered about the practicality of reforming the process in that way. Regarding Pleasant’s comment about outcomes, Sudore responded that the potential for liability when discussing outcomes is higher when the physician does not know the patient who is being asked for consent and does not know what that person’s desires and goal are relative to the treatment procedure in question.

Michael Villaire noted that his organization and others teach the principles of health literacy to people who create forms and who write patient education materials. “We give them all of the basics on how to use white space and plain language and graphics and limit messages and all of those principles that at least remove barriers to comprehension,” he explained. “Nothing will ever guarantee comprehension, but we can at least take out as many barriers as we can see.” Where the process of creating health-literate consent forms and education materials fails is often when they reach a company’s attorneys, he said. “There is often a power imbalance in many organizations where the patient educator, the person writing these forms, does a great job in creating these documents. Then it goes to legal, and that’s the end of it,” said Villaire. He asked Trudeau if he had any ideas on how to approach the legal department and start a conversation over the balance between understandability and legal obligation.

Trudeau noted that he was preparing a 3-hour answer to that very question that he would be presenting to the FDA the day after the workshop and that he could not do justice to this question. He did reiterate his earlier statement that the problem lies in the balance of power, with the lawyers in the power position. “In reality they [lawyers] don’t know what they are talking about when it comes to creating an understanding. They know what they are talking about when it comes to protecting the client,” said Trudeau. Correcting that imbalance is what drove him to create simplified forms that he can use to show lawyers that their client protection goals are not incompatible with health literacy goals. It also drives him to try to recruit others in his profession to become what he calls “health literacy lawyers.” “We have a lot of health lawyers in the country,” said Trudeau, “people that know everything about HIPAA [Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act] and the Affordable Care Act, but they are not necessarily the best health literacy lawyers. We need to teach those folks and that, I think, is going to pay dividends in the long run because you will get some of those folks that could be champions for you.”

Villaire asked how to start the process of creating a cadre of health literacy lawyers, and Trudeau said the first step should be to provide plain

language training to lawyers in the health care field and to convey the fact that plain language can provide greater protection to their clients. At the same time, it is important to recognize that lawyers will always put client protection first because that is how they were trained, and it is why they were hired in the first place.

Referring to Sudore’s anecdote about the woman whose directives were not in sync with her wishes, roundtable member Winston Wong asked if there was a way to systematically document the health literacy capacity of both the patient and family members. Is there a way, he wondered, to document that patients have spoken to their family members about their wishes and that the family members understand the implications of the patients’ decisions. “Is there a role for family health literacy to be part of this solution?” he asked. Sudore replied that this issue arises all the time, such as when dealing with patients with severe dementia or when addressing advance care planning. What she does is to make sure that family members are part of the discussion and then to use teach-back with both the patient and the family. “For instance,” said Sudore, “somebody will say to me, ‘This is what I want, and here are the reasons.’ We will talk about that, and then I will turn to a family member and say, ‘Did you just hear what [somebody] said, and can you say in your own words what that means to you?’” She then documents that this conversation took place. Trudeau added that he has added places where caregivers also need to demonstrate understanding for procedures, such as signing on for insulin infusion pump therapy, and he reiterated the idea that the discussion that proceeds signing the form is just as important as getting that signature on the form. He added that educating caregivers would probably be beneficial from a legal standpoint, too.

Benard Dreyer commented that his institution forbids the use of preprinted consent forms. He asked Trudeau if there were any question-based template guides that would allow people to create a form similar to his colonoscopy form and if he had given any thought regarding how to institute those templates in medical care. Dreyer thought such templates would be useful for procedures that are not as common as colonoscopy and for which preprinted forms do not exist regardless of the institution. Trudeau said that he needed more time to think about this problem, but he did note that the question-and-answer format itself can serve as a template from which a well-trained physician could create a form. He suggested that the IOM or AMA could create templates for most procedures, and then the templates could be used to individualize forms for even rarer procedures. He added that it might not be a bad thing to force lawyers and doctors to work together to create forms for use with some rare procedures that entail a major risk.

Lindsey Robinson, president of the California Dental Association, commented on how much she values the work that Trudeau is doing and the

empirical research he provided to the roundtable. She then asked Sudore if she could expand on how the advance directive can reflect health literacy principles, given that directives are often drafted in a lawyer’s office. Sudore said that advance directives can come from many places, including from nurses and doctors. She then recounted a story from her own family involving her grandmother’s advance directive. Her grandmother had to be hospitalized, and when Sudore asked her father where her grandmother’s advance directives were, he told her everything was okay because they were with the family lawyer. Sudore then asked her father if the doctor had a copy because the lawyer was not the one treating grandma in the hospital.

“I think a lot of times the lawyers do a good job, but not always,” said Sudore. “I have met many dedicated lawyers who want peoples’ voices to be heard and actually sit down and have conversations and document them, but then they [the documents] stay at the lawyer’s office, or they stay in somebody’s file cabinet rather than make it to the doctor’s office. I would say that even with the advent of electronic medical records, if somebody could figure this one piece out—I know there are a lot of companies looking at cloud-based options and things like that—that could really help.” She did mention that the American Bar Association has an app that allows individuals to upload to their phone the documents created by their lawyers.

Robinson asked Sudore to comment on a personal story involving her own mother, who was diagnosed with a terminal pulmonary disease. Robinson’s mother’s primary care physician would not refer her mother to hospice, even though that was her mother’s and the family’s desire, because this physician once had a patient who had outlived the permitted stay at hospice. Sudore said that she discharges patients from hospice care frequently and that there are studies showing that people who get palliative care live longer. “If someone graduates from hospice, it is usually not a problem,” said Sudore.

George Isham also provided an anecdote about advance directives and estate planning, an exercise he recently completed. At one point, the lawyer suggested including an option that would allow two doctors to determine whether Isham would want treatment if he were otherwise incapacitated, an idea that Isham thought was the worst possible recommendation that he could imagine. “It seems that we are approaching this document with very different assumptions depending upon whether you are a lawyer or whether you are using it,” said Isham, and he wondered if there might be some upstream remedies to that fundamental issue in terms of viewing the document as more than just a legal document, but rather being explicit about that in terms of training lawyers as well as doctors and other health professionals.

He also wondered if the experts in this field ought to be challenged to think more about the time dimension regarding when to start the consent

process and the information requirements associated with the progression from being well and doing advance planning to then developing a disease and having to make some of these decisions in a more immediate time frame. “It seems like there is a model or framework that needs some good intellectual work to suggest when it is appropriate to have which conversations and what kinds of issues and domains to discuss and then make some proposals about a systems approach to handling these issues,” said Isham.

Sudore responded to Isham’s comment by noting that too much of advance planning is focused on the end of life and that much of her work aims to bring that process upstream, to redefine the planning in advance planning. She added that advance planning should not be just about CPR and mechanical ventilation; it should also be about helping people even when they are healthy learn how to talk to their doctors, how to identify what is important to them, and how to translate those desires into the right medical care, whether that be starting a blood pressure medication or having elective knee surgery. Trudeau voiced his approval for starting the process earlier in life and said that although there could be a synergy between what Sudore does and what he does, it is probably not feasible yet to merge the two efforts. Sudore replied that she is in fact working with faculty from the University of California Hastings School of Law and that there are medical and legal partnerships forming.

Lori Hall, consultant on health education at the Lilly Corporate Center and a roundtable member, asked Trudeau if he could see informed consents coming into the realm where quality would be judged according to some metrics on plain language. Trudeau responded that judges are the ones who now do the measuring and that is why he believes that convincing one judge of the merits of a lawsuit based on low-health-literacy consent documents would have a major impact. He acknowledged that metrics might be useful but that he had not given it much thought yet.

Wilma Alvarado-Little commented on the fact that some of the forms she sees have signature lines for witness, patient, responsible party, and physician. Others have signature lines for patient legal representative and witness or for patient, witness, and physician, and she wondered if there was any significance to these different formats. She also asked if there should be a place for her to sign as an interpreter—not as a witness, which would be inappropriate—to represent that the patient was given information in a language-appropriate manner. Trudeau replied that whether these differences are significant has to do with state regulations. Some regulations require a witness signature, others require it only for certain types of treatments, but having a witness signature even when it is not required will not cause any problems. He also remarked that some countries do make provisions to have the interpreter’s signature on the consent form, and he

thought that adding such a provision to consent forms would be easy to accomplish and a good idea.

Bernard Rosof told the workshop that during the discussion he looked at the website of the American College of Gastroenterology to see what it had to say on the matter of informed consent and found an entire PowerPoint presentation using many of the discussion points that had been raised at this workshop. In particular, three bullet points seemed important to him. The first was that shared decision making among patient, family, and physician is the key to obtaining legally effective informed consent regardless of what consent form is used. The second point was that, in Louisiana, an expert advisory group develops a list of material risks that is updated on a regular basis for physicians to use. The third point was that current lists and shared decision making are the primary keys to maintaining a constitutionally valid informed consent statute. Trudeau commented that Louisiana is unusual because its legal system is derived from the French system and therefore is based more on civil law rather than common law. Although the principles are similar, the list of requirements will be longer under civil law. He noted that any consent form that he would draft would include all of the risks as listed by the expert advisory group because the form has to comply with state regulations.

The final question for this panel came from Brach, who asked Sudore to clarify how she presents the best-case and worst-case scenarios to patients and to comment on whether she elicits not only a patient’s preference but also their understanding of how likely the different outcomes are for their choices. Sudore replied that she and her colleagues do present patients with that information and that they do communicate to patients how likely each outcome is relative to the other. She noted that the most likely and least likely scenarios are going to differ according to each patient’s health status.