5

The Future of Informed Consent

The workshop’s final panel featured two presentations on how informed consent may evolve over the coming years. Kenneth Saag, the Jane Knight Lowe Professor of Medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, discussed ways in which information technology could improve the informed consent process. Michael Paasche-Orlow, associate professor of medicine at Boston University School of Medicine, spoke about the need to create a culture of change that can drive improvements in the informed consent process. An open discussion followed the two presentations.

INFORMED CONSENT, CLINICAL TRIALS, AND INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY1

Kenneth Saag

University of Alabama at Birmingham

As an example of how information technology can improve the informed consent process, Kenneth Saag discussed how he and his colleagues are using an electronic consent platform to address the challenge of obtaining informed consent in the context of pragmatic clinical trials. Pragmatic clinical trials, he explained, measure “real-world” effectiveness

_____________

1 This section is based on the presentation by Kenneth Saag, the Jane Knight Lowe Professor of Medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the IOM.

and not efficacy, using large sample sizes to produce results that are generalizable. He noted that the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) and the NIH Research Collaboratory, among others, are investing substantial resources in developing the infrastructure to conduct pragmatic clinical trials.

Pragmatic clinical trials use less-restrictive patient eligibility criteria, broader patient populations, and simpler treatment arms than the traditional randomized controlled trials used for drug approvals, Saag explained. The goals of well-designed and executed pragmatic clinical trials are to involve community physicians and study sites that are not typically included in traditional phase III clinical trials, to create a learning health care environment, and to turn routine clinical care into a potential research encounter (Chalkidou et al., 2012). Saag said that there are many challenges to achieving those goals, however, with cost being the biggest one. As an example, Saag cited the $125 million Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) study that showed that low-cost thiazide diuretics were as effective as more expensive antihypertensives at reducing mortality in patients with clinically advanced peripheral artery disease. Although this study was undoubtedly valuable, the nation does not have the resources to conduct many pragmatic clinical trials at this price, he said.

Improving the efficiency and effectiveness of conducting pragmatic clinical trials will require addressing several other challenges, Saag said, such as the need to efficiently collect data and conduct study procedures that include recruiting patients, measuring outcomes, and obtaining informed consent (Eapen et al., 2014; Warner et al., 2013). Meeting the complex regulatory requirements of multiple IRBs, institutions, and partners involved in large multisite studies is another real challenge, as is engaging busy practicing clinicians and clinical staff who are not charged with conducting research as part of their daily responsibilities.

Saag explained that there are also a number of challenges for using informed consent in pragmatic clinical trials. For example, there are few validated methods for soliciting effective, efficient, and ethical informed consent in the community setting at sites with limited research expertise. Few community practices, he added, have dedicated research staffs or on-site coordinators, let alone IRBs, with the know-how or certification to oversee research. In addition, optimizing study participant comprehension and satisfaction while minimizing the burden on the staff is a significant challenge to overcome, he said.

Electronic informed consent may offer one approach to addressing these challenges. Saag noted that, for researchers, electronic consent offers several potential benefits. It is a paperless process, one that reduces administrative burden yet still allows a copy to be printed for study participants

or an IRB. Electronic consent can provide the opportunity to follow study progress at multiple sites, yet allow the flexibility to alter the consent form to meet the requirements of local IRBs or translate it into other languages, and it can provide real-time monitoring of recruitment and the informed consent process. Interactions are recorded immediately into a tracking system, creating an audit trail of timed and dated information on the consent process. Saag pointed out that electronic consent can improve security and privacy protections via the ability to upload data to a remote, central site and remove it from the specific device used to collect patient information and consent.

There are potential benefits for the study participant as well, he said. Electronic consent, explained Saag, is patient centered because it allows participants to review the consent with the family, particularly if the study allows for online or at-home enrollment. Electronic consent can also include audiovisual aids, other educational information, dictionaries, and translational capabilities aimed at increasing comprehension, and it can include real-time knowledge assessment to determine whether a participant truly understands the consent materials.

There are challenges to using electronic consent, however, said Saag. Start-up expenses are high, given the cost of building the initial infrastructure needed to manage online documents, validate electronic consent, and even verify the identity of the participants in direct-to-patient studies. There are also compliance challenges regarding electronic data and data security as required by Title 21, Part 11 of the Code of Federal Regulations, which imposes certain requirements on an entity when it chooses to maintain FDA-required records and signatures in electronic form. Electronic consent can also present challenges for participants, given that not everyone is familiar or comfortable with new electronic technologies and that electronic consent can make it more difficult to have consent discussions with investigators. Participants might also have confidentiality concerns in terms of who will have access to the consent documentation and the answers given to screening questions. Saag said that he and his colleagues have tried to make their electronic consent application as simple as using an ATM machine.

Citing a study that Sara Goldkind mentioned during the workshop’s second session (Flory and Emanuel, 2004), Saag said that a systematic review of 12 trials using multimedia as a means of improving comprehension in the consent process found that only 3 of the studies showed significant improvement in participant understanding. The authors of that study concluded that having a study team member or a neutral educator spend more time with the patient was the best way of improving research participants’ understanding. However, noted Saag, having a study team member or a neutral educator spend more time with the patient is not going to be practical for studies involving thousands of patients at hundreds of sites.

“We can’t add more personnel to the equation,” said Saag. “We need to figure out how to do it cheaper and more efficiently in addition to maintaining adequate understanding and comprehension.”

To illustrate how he and his colleagues are addressing these challenges, Saag discussed the Effectiveness of Discontinuing Bisphosphonates (EDGE) trial, a pragmatic study of 9,500 subjects at about 300 study sites to look at the effect of either continuing or discontinuing alendronate therapy for osteoporosis. The study was designed to answer the question of how long patients should stay on this drug, given reports of rare but severe adverse side effects. Participants are screened, asked for consent, and randomized using a tablet application. The study design adheres to the principles of pragmatic clinical trials: minimal inclusion and exclusion criteria; limited patient responsibilities and minimal commitment of time for providers; same-day single-visit enrollment; and dynamic randomization performed centrally on the day of that visit. Saag noted that the EDGE team is networking with primary care physicians to create a practice-based research network. Another innovation in this study, he said, is that it links to data that are collected more passively, such as Medicare and insurance data and electronic health records, as a means of trying to lower the cost of conducting such a study.

Saag talked about the results of a pilot study designed to test the feasibility of using tablets for enrollment and consent and to develop some of the tools needed for the EDGE study. The pilot found that 80 percent of the 160 women 65 years or older who were asked to participate in the study agreed to complete the osteoporosis screening questions in 10 different family physician offices (Mudano et al., 2013). In general, the women who completed the screening questions preferred the tablet over an interactive voice response system (see Table 5-1), and they were able to use the tablet without too much difficulty and without significantly burdening the staff or interrupting workflow. Saag inferred that, compared to the voice interactive response system, the tablet was judged easier to use and understand and was less time-consuming. Users of the tablet were more likely to express an interest in participating in future trials, and they reported that they would not mind spending extra time in their physician’s office to enroll in a study, Saag said.

A second pilot study, using the Mytrus electronic consent platform, compared pen-and-paper consent with electronic consent and was conducted as a mock trial in order to more closely model how potential participants would behave in a real trial. Saag noted that the reason for not conducting this pilot study as part of a bigger study was that investigators did not want to use an unproven technology in their trials. He also explained that the hypothesis for this pilot, which was conducted at nine primary care sites, was that clinics and patients would prefer the tablet

| iPAD (n = 93 pts.) | IVRS (n = 67 pts.) | |||||

| Strongly agree or disagree | Neither agree nor disagree | Strongly disagree or disagree | Strongly agree or disagree | Neither agree nor disagree | Strongly disagree or disagree | |

| The iPAD/phone was easy to use | 78 (85.7%) | 4 (4.4%) | 13 (9.9%) | 58 (86.6%) | 2 (3.0%) | 7 (10.4%) |

| The questions were easy to see/hear | 88 (96.7%) | 1 (1.1%) | 2 (2.2%) | 61 (91.0%) | 3 (4.5%) | 3 (4.5%) |

| The questions were easy to answer | 90 (97.8%) | 1 (1.1%) | 1 (1.1%) | 64 (95.5%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (4.5%) |

| The process did not take too long | 84 (91.3%) | 1 (1.1%) | 7 (7.6%) | 61 (91.0%) | 3 (4.5%) | 3 (4.5%) |

| If eligible, I would be interested in participating in osteoporosis drug trial | 32 (35.2%) | 22 (24.2%) | 37 (40.7%) | 13 (20.3%) | 18 (28.1%) | 33 (51.6%) |

| I would not mind spending extra time at my doctor visit to enroll in the study | 37 (41.1%) | 17 (18.9%) | 17 (18.9%) | 17 (26.6%) | 20 (31.3%) | 27 (42.2%) |

NOTE: IVRS = interactive voice response system.

SOURCE: Mudano et al., 2013.

over pen-and-paper consent, leading to improved efficiencies and a more effective consent process. All told, 41 participants were screened, and 31 were enrolled in the pilot.

As Linda Aldoory explained in her earlier presentation at the workshop, the Mytrus system has been vetted by more than 30 IRBs in the United States and abroad, and the FDA has encouraged its use in clinical trials. Saag noted that the consent form is embedded in the tablet application. Participants can scroll back and forth through the consent form to see different parts of it as they complete the consent process. The platform also allows participants to click on terms they do not understand and get additional illustrated explanations, and it includes quiz questions to ensure that the participants understand key concepts of the study and the consent process.

The Mytrus application also collects some preliminary demographic data and links individuals to their Medicare data. After the participant has signed the consent document electronically, the tablet application also verifies inclusion criteria and randomizes participants dynamically via links to the Web. Saag acknowledged that although this system has been approved by many IRBs, there is still some controversy associated with it, the reasons for which he did not discuss in his presentation.

Although the pilot involved a small number of participants, Saag said that the data suggest that participants trended toward being more interested in using the tablet than in using pen and paper and that their comprehension was better using the tablet. The study design also allowed Saag and his team to compare what providers thought about the tablet compared to pen and paper, and there was some indication that the tablet was better received among providers.

Saag also reviewed a prospective randomized study that Mytrus conducted comparing both participant and researcher satisfaction using its interactive tablet application or an IRB-approved pen-and-paper consent form (Rowbotham et al., 2013). The results of this study showed that overall satisfaction and overall enjoyment slightly favored the tablet presentation among both participants and researchers and that combining an introductory video, standard consent language, and an interactive quiz on a tablet-based system improves comprehension of research study procedures and risks. Saag noted that the tablet consent process took longer than pen and paper.

Summarizing what he thinks about the use of electronic consent based on the results of these pilot studies and his reading of the literature, Saag said that informed consent barriers are a particular concern when considering the growing national interest in pragmatic clinical trials. Platforms do exist that use multimedia information technology to facilitate the informed consent process. Preliminary data suggest similar to better effectiveness

and satisfaction, with adequate efficiency, compared to traditional pen-and-paper consent. He cautioned, though, that regulatory and economic barriers may delay the widespread implementation of electronic consent technology. Regarding the policy implications of electronic consent, Saag said that there are a number of questions that need answering. What, for example, are the best study types for electronic consent? Would it be simpler studies, pragmatic trials, direct-to-patient trials, or more complicated studies? What are the best patient populations for using electronic consent? Is it those that have lower literacy or who are not native English speakers and who might find illustrations helpful? Would children, who tend to like playing games, benefit from electronic consent forms? Saag noted that there has been some research to suggest that mentally ill patients may do better with multimedia consents.

When it comes to researchers, his focus has been on community-based physicians who may lack sufficient staff and expertise or the infrastructure to support the consent process associated with clinical trials. “If we can link this to the electronic health record and make this part of the learning health care environment, I think we will have gone a long way,” said Saag.

INITIATING A CULTURE CHANGE AROUND INFORMED CONSENT2

Michael Paasche-Orlow Boston University School of Medicine

Michael Paasche-Orlow began the workshop’s final presentation by stating that he believes people should be angrier about the current state of informed consent. Paasche-Orlow used terms such as “travesty,” “sham,” and “a shame” to characterize the current state of informed consent. In his mind, risk managers do not care enough about informed consent, appear to be stymied by their own aversion to change, and fear using new models for informed consent that are available. He said that providers and researchers do not care enough because informed consent is not their priority, and patients do not care enough because they have become acculturated to checking off consent concepts everywhere they go. It is hard to change these attitudes in the health context. “It’s actually much more work to learn all the things we want them to learn,” said Paasche-Orlow.

He then addressed what he sees as the goals of the consent process. Liability protection seems to be the number one goal these days, he said, but

_____________

2 This section is based on the presentation by Michael Paasche-Orlow, associate professor of medicine at Boston University School of Medicine, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the IOM.

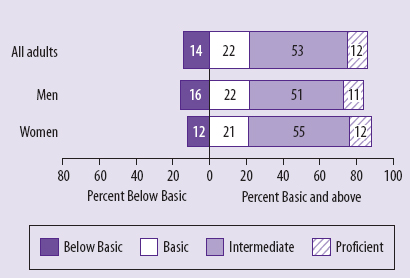

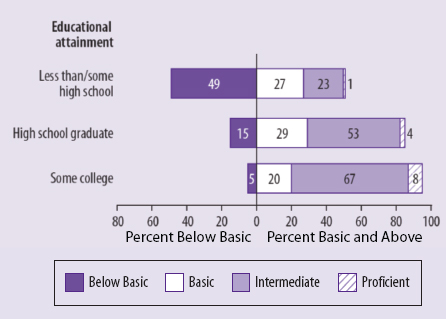

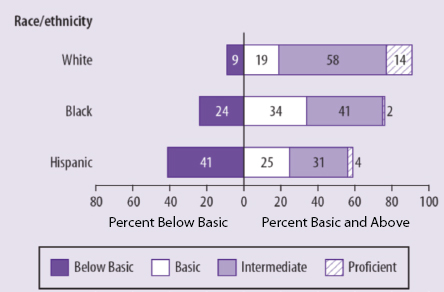

informed consent should have the goals of serving an ethical duty, empowering patients, and strengthening trust between patient and physician or study participant and researcher. A health-literacy analysis can further all of these goals, he said, but it will take a major cultural change to bring health-literacy concerns front and center, and the field should not wait for regulatory change or the evolution of jurisprudential norms to make that happen. He also noted that these concerns are tied heavily into social justice, given how low the rate of health literacy is in the U.S. population (see Figure 5-1), particularly among those individuals with less than a high school education (see Figure 5-2) and among members of ethnic and racial minorities (see Figure 5-3).

Paasche-Orlow then described research that he conducted 11 years ago that looked at the readability of informed consent forms compared to the standards set by the organizations that created them (Paasche-Orlow et al., 2003). He and his colleagues extracted relevant data from 114 of 123 medical school websites. Of these, 61 (54 percent) had a grade level standard in the 5th- to 10th-grade levels, and 47 (41 percent) had descriptive guidelines such as “in simple lay language.” The mean Flesch-Kincade grade level across all of the templates was 10.6, but in schools with a specified grade-level standard, only 5 of 61 (8 percent) met their own specific standards

FIGURE 5-1 Percentage of U.S. adults in each health-literacy level.

SOURCE: National Center for Education Statistics, 2003.

FIGURE 5-2 Percentage of U.S. adults in each health-literacy level by highest educational attainment.

SOURCE: National Center for Education Statistics, 2003.

FIGURE 5-3 Percentage of U.S. adults in each health-literacy level by race/ethnicity.

SOURCE: National Center for Education Statistics, 2003.

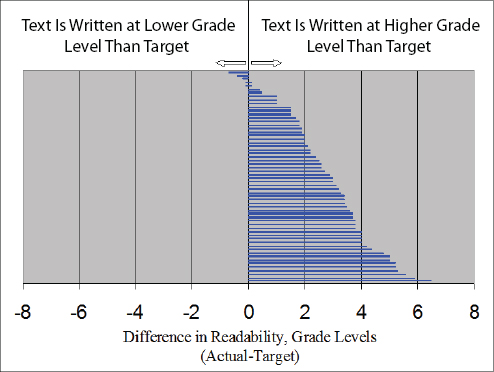

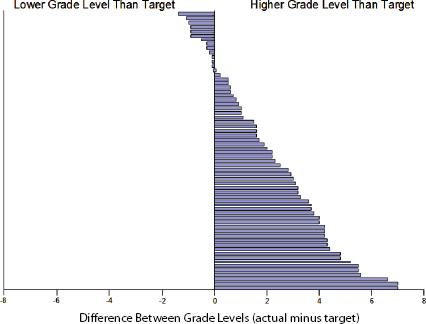

(see Figure 5-4). On average, the consent forms from those institutions tested at nearly three grade levels higher than the stated standard. Paasche-Orlow called this difference the “hypocrisy index.” When he repeated this exercise a decade later, he found that the hypocrisy index improved slightly, but that it was still unacceptable (Paasche-Orlow et al., 2013). Ten years after his initial study, the mean Flesch-Kincade grade level across all of the templates had dropped to 9.8, and 12 percent now met their own standard, with the average template scoring a little over two grade levels higher than the standard (see Figure 5-5). However, this improvement is only evident because he had examined HIPAA language separately, as this language had not been in place at the time of the initial study.

In fact, inclusion of the HIPAA-mandated text only made matters worse. Including HIPAA-mandated language increased the mean Flesch-Kincaid grade level to 11.6, and only 8 percent of institutions were able to meet their own standards, with the average template scoring over four grade levels above the standard. “This sends a very, very bad message to all

FIGURE 5-4 Actual versus target readability scores for the 61 institutions with stated standards in 2003.

SOURCE: Paasche-Orlow et al., 2003.

FIGURE 5-5 Actual versus target readability scores for the 64 institutions with stated standards in 2013.

SOURCE: Paasche-Orlow et al., 2013.

of the investigators and all of the clinicians out there. We are telling them to do a better job, but the templates from the organizations themselves are deplorable,” said Paasche-Orlow.

Reiterating what other speakers had said regarding informed consent being a process, not just a form, Paasche-Orlow said that it would nonetheless be cynical not to do a better job of acting on research that shows that simplifying and shortening informed consent forms improves understanding. In fact, he said, the forms can be useful because patients and participants can take them home and learn from them, and the forms can inspire questions and further discussion with clinicians and researchers. They can even inspire staff to do better. In the end, though, readability will only be part of the answer, given that some concepts, such as randomization or conflict of interest, will still be confusing to patients and participants. He also reinforced the message that others at the workshop had delivered, which is that it is impossible to know what people do and do not understand unless there is a mechanism to test for understanding. “Without checking, without confirming comprehension, you just won’t know what people understand or don’t understand,” said Paasche-Orlow.

What is needed, he said, is a massive cultural shift—not a subtle one—that has to occur at the organizational level, at the practitioner and investigator level, and at the patient level. This shift, he said, requires moving from persuasion to pedagogy. He said that when he listens to audiotapes of the consent process, the basic thing that he hears is persuasion. “The clinicians, the investigators are trying to persuade someone to do something,” said Paasche-Orlow. Shifting to a model based on pedagogy will flip the default situation from one in which the patient or participant has to step forward and ask for more information to one that embraces a positive ethical duty to ensure and document substantive comprehension.

“When an investigator or research assistant or a clinician says, ‘So do you have any more questions?’ I would say that is not an honest play for an interaction to learn about questions,” said Paasche-Orlow. The reason it is not an honest attempt to judge a patient’s comprehension, he explained, is that the medical profession has taught the general public that its time is not as important as a doctor’s time. “We have acculturated people to say be quiet,” explained Paasche-Orlow. Referring to Yael Schenker’s likening the current process to the Miranda warning, Paasche-Orlow said that the situation is worse than one in which the patient or participant has the right to remain silent. “You sign this form, and we are going to imply to you that you can’t sue us,” he said. “Once you sign this form, it is some kind of weird act that you sign this form and give away your rights. Actually, it is not supposed to give away your rights, but that is how people understand it. They think this is some kind of a contract where they have lost rights by signing the form.”

Paasche-Orlow said the deck is so stacked against the patient or participant that, in fact, they do not even read the consent document in many cases. Studies that he and his colleagues have conducted using gaze tracking show that even when given the time to read the consent document, patients and participants are not really reading it.

One question that intrigues him is how organizational leaders, clinicians, and research staff learn about the consent process. Many research assistants report that they do not get any training at all, so part of the move toward pedagogy will require that everyone involved in the consent process receive adequate training and supervision and that institutions implement quality control metrics to ensure that staffs are properly trained. Paasche-Orlow recommended that there be a national survey of training, supervision, and documentation approaches in order to compile best practices that could be relevant to the informed consent process. He also recommended that the nation should establish a model training program for investigators, clinicians, organizational leaders, and patients. He noted that successful large organizations outside of health care devote significant resources to training, monitoring, quality control, and feedback, and that it is time for

health care organizations to follow suit to improve and support informed consent.

Paasche-Orlow cautioned that “we do have to be humble about these things,” given that people have tried to develop interventions in this area, but many have not succeeded. Part of what will need to be done is to test different models on the basis of pedagogy. His group, for example, has been thinking about this problem in terms of general adult education and looks at the person doing the consent process as an educator. Taking that perspective leads to an examination of the materials that are available to educate the patient or participant. Today, for example, there is no teaching version of consent forms, so Paasche-Orlow recommended that institutions create a teacher’s version that embeds all of the things that you want them to do—this is a common pedagogic practice that educators use outside of health care—and then see if they actually take all of those actions. “If you want to have a result, you should check it,” said Paasche-Orlow.

Part of the idea of confirming comprehension, he explained, is that it can shift the goals of the people involved in the consent process. The goal today for the most part is to get people into the system, whether it be for surgery or other procedures or as study participants. Making a cultural change that turns research assistants or nurses or surgeons into educators gives them a different job and a different goal. He noted, as had earlier speakers, that the physician may not be the best person to conduct the consent process. In fact, in his experience, physicians are the least likely participants in the consent process to change their behavior.

Taking this approach will create opportunities for monitoring and providing feedback on what works and what does not. It can, however, decrease patient and participant satisfaction because it often increases the time to complete the consent process, said Paasche-Orlow. Again, a culture change is needed to create an environment that alters the public’s perception of why the consent process is important and why patients should truly understand the information they receive during that process. He noted that patients often believe that their physician, whom they trust, would not put them in the placebo arm of a trial, because they misunderstand the research process.

A shift has to happen at the organizational level, too, one that emboldens leadership to support creating interventions that will address current structural problems. One problem that must be addressed, which other speakers referred to, is the Hobson’s choice that surgery patients often face. He explained that a Hobson’s choice is an ethical scenario in which neither choice is good. In the case of the patient being prepared for surgery, the Hobson’s choice is either sign the consent form with no real comprehension, or there will not be surgery.

Part of the solution, said Paasche-Orlow, is advocacy. Time is money in

these organizations, and solving this problem requires an ongoing program of training, supervision, and evaluation that will be implemented only if patients and prospective study participants advocate for health systems spending the necessary money to create those programs. On the practitioner side, he said, there is an overt culture that needs to be developed to override the hidden culture that exists in the medical profession. “Every single time the attending says to the lowest person on the team, ‘Go consent that person,’ it is a very, very strong hidden message that ‘I don’t care about this,’” said Paasche-Orlow. Recognizing and understanding this hidden culture is necessary to eliminate it from the culture of the organization.

He also said that the professional standard for judging when to do consent is inadequate. In his opinion, a patient is asked for consent based more on professional traditions than on the actual level of risk, but Paasche-Orlow said that what is risky is in the eye of the beholder. “Why is it that you consent for every little punch biopsy of a mole, but you don’t consent for incredibly toxic pills that the doctor gives you?” he asked. The answer, in his view, is that there is some kind of convention about surgical procedures versus pills. “We have all kinds of biologics that are incredibly dangerous, but no consent is happening,” he said.

Instead of this tradition-based, professional standard, the decision on what needs consent should be based on what a reasonable patient would want to know. For a relatively dangerous drug, patients should truly understand the possible side effects and the risks involved in taking the drug or stopping therapy at some point in the future. “The professional standard has not been a good guide of where this should be done,” said Paasche-Orlow. In his opinion, research in health literacy has revealed the risk that the professional standard can lead to racial or cultural bias. Simply giving patients time to read a form is not enough, he said in closing. The cultural agenda for physicians has to become one that promotes shared decision making, and there needs to be an advocacy agenda to promote such a culture. He also summarized his recommendation as follows:

- Shorten the forms.

- Simplify the forms.

- Require documentation of comprehension.

- Conduct a national survey of training, supervision, and documentation approaches.

- Establish model training programs for health system leaders, clinicians, investigators, patients, and families.

Cindy Brach started the discussion by recounting the results of an AHRQ project demonstrating the Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit (DeWalt et al., 2010). This demonstration project attempted to use tablets to help overcome literacy barriers, but of the 10 practices selected to participate in this project, half ended up using paper and pencil because of several problems, including slow Internet connections, their patients’ preferences, troubleshooting challenges, and others. “I just want to point out that I don’t think we are quite there yet for those kinds of solutions,” said Brach. With that in mind, she questioned whether Paasche-Orlow’s recommendation to conduct a national survey of best practices was in fact doable today. She then asked him for any ideas he might have on what documentation of confirmed understanding would look like and how it would function as one of the levers to achieve cultural change in an organization. Paasche-Orlow first responded that he likes the Brief Informed Consent Evaluation Protocol (BICEP), which was developed by Jeremy Sugarman and his colleagues and is administered by a third party via telephone interview immediately following consent (Sugarman et al., 2005). He then explained that at the end of the toolkit, there is a form for evaluating comprehension in the context of research that would provide a document that people could examine and then discuss with the staff.

Saag remarked that it is important not to discount the potential for technology to improve the informed consent process just because some physicians are reluctant to overcome the challenges inherent in switching from pen and paper to tablets. For example, Saag said, “I would argue that one size fits none. Maybe tablets are not at all what we need to use, and then again, it may not be that you need Wi-Fi and that maybe a WAN [Wide Area Network] signal is sufficient. Maybe people are going to be doing more of this at home. Maybe they are going to be using the kiosk in the waiting room. These are all things that are very rapidly changing, and I think we should think more about what the technology can bring and less about the hardware.” He then recounted a recent experience in which he and his collaborators were going to use storytelling via a Web-based application, and the grant review committee said that there also had to be a DVD available for those who did not use the Web. His team did spend the money and time developing the DVD, but in the end, nobody used it—everyone went to the Web. “When we try to dumb down the technology, we are always a step behind,” said Saag. He also referred to recent polling numbers showing that use of the Web continues to grow, even among older Americans. Paasche-Orlow noted that even his homeless patients have phones, many of them smartphones.

Laurie Francis commented that she believes there is a way to go to get to a place where patient priorities and preferences drive all conversations, and she agrees with the Hobson’s choice analogy that Paasche-Orlow noted. “That idea of shared decision making isn’t about us taking time for the patient to get on board with our decisions but, in fact, is bidirectional. I would love for us to confirm understanding and use teach-back,” she said. Paasche-Orlow responded by saying that he had just finished 1 month on the wards and heard clinicians complaining frequently that they spend more time with the computer than they do with the patients, a sentiment for which he has little compassion. He then commented that he believes that values clarification and bidirectional agenda setting is potentially time saving. He also thinks that insurers should get involved by stating that meeting patients’ agendas matters to them. Paasche-Orlow did acknowledge that perhaps agenda setting might need to happen in a more complicated way, perhaps by first meeting with another staff member to determine that agenda. He noted that there have been studies looking at that type of activity.

Andrew Pleasant commented that it may be useful to look at the social sciences for a model of how to change culture, given that social sciences researchers approach people from very different perspectives. He noted that some of the missing best practices in a clinical context may already be available from the social sciences.

Ruth Parker thanked Paasche-Orlow for his recommendations and wondered if there might be another item on that list, that is, to better understand what the public wants and needs to know about various health care–related topics, whether that topic be what various drugs do or what some surgical procedure entails. Similarly, she thought it might be useful to know what pharmaceutical companies, for example, have learned from their own safety and efficacy studies about what patients need to know. Paasche-Orlow agreed that the lack of understanding about what patients want to know is a serious problem. He noted some work that he has done in which he asked various clinicians about what they thought a patient would need to know about various medications, and the agreement among them was “horrendous.” He also said that what patients know today about their medications largely comes from direct-to-consumer advertising, and he has had patients come in asking if they can please have a particular side effect that was mentioned in an advertisement. He then recounted work that he and his collaborators have done to identify the critical information that patients need for more than 1,000 drugs. They also prepared a set of additional questions, with the corresponding answers, that patients who want more information might ask. Despite the researchers’ spending thousands of hours preparing that supplementary information, patients never

used it. However, when he asked patients if they need that information in the system, they said they did.

Saag said he believes that part of the problem is that, because of the driving force of risk aversion, “we are busy [getting the consent] for things that aren’t important, both in clinical care and in research studies, and so we are not doing a good job when it really matters.” He suggested that what is needed is a public relations campaign to get out the word that getting medical care is dangerous and that there is a benefit to being part of a learning health care system. “There is a public good in doing that, and there is an ethical framework for promoting that,” said Saag. Focusing on what is important and getting rid of the superfluous content in consent forms would improve things dramatically, he added.

Benard Dreyer applauded Paasche-Orlow for his anger at the current state of the field and commented that the powers that be are all happy with how the system works today and that getting them to change, in his experience, is nearly impossible. He also recounted his experience with an effort to train all of his institution’s pediatricians to use teach-back with regard to asthma treatments. During the study, all of the pediatricians used teach-back, and they did it effectively, said Dreyer, but when the research project stopped, the pediatricians stopped using teach-back immediately. He asked Paasche-Orlow if he had any ideas on how to sustain good practices in the face of this type of behavior. Paasche-Orlow replied this is not a set-it-and-forget-it activity, like roasting a turkey. “This is one of those kinds of things that require supervision and feedback,” he said. Various studies and his experience support that need. He did note that some health care professionals, particularly pharmacists, are easier to train and to persuade them to continue in these kinds of activities. He also said that this is a broader cultural issue. “For whatever reason, medical schools somehow communicate one way or the other that patient education and empowerment is somebody else’s job,” said Paasche-Orlow. Both he and Dreyer characterized their efforts at training doctors to be Sisyphean in that regard.

As for how to change culture at the level above the physicians, Paasche-Orlow said that culture change takes leadership and gumption. One approach might be to find lawyers who can be compatriots in this effort and to get insurers more involved in setting an agenda. “There is a lot of power in that room that hasn’t been tapped for this agenda,” he said. Saag agreed with these ideas but worried about placing yet another burden on primary care physicians, who already have too much to do. “We have to come up with a solution that doesn’t involve adding more responsibilities to primary care providers,” said Saag, who suggested that pharmacists, nurse educators, and others could take on the added responsibility of agenda setting and better understanding patient desires and needs.

Robert Logan asked Paasche-Orlow if the pedagogically oriented paradigm that he advocates is more about decision making or about empowering those who have the least influence in the consent process, namely, patients and caregivers. Paasche-Orlow replied that he would like it to be about empowerment and that shared decision making can be empowering for people. One of reasons that he worries about the subjective standard is that people often judge what others need to know on the basis of what they look like or how big a vocabulary they have. “You can see that people who are more educated are given more information by their clinicians,” he said.

Kim Parson reiterated the idea that one size does not fit all regarding what technologies are appropriate to use in a given setting. Each person, she said, has his or her own style of learning and is in his or her own space in terms of health needs at a particular moment in time. She also stressed the importance of discussion and of the finding that most people, regardless of literacy level, are unable to recall or understand the information presented to them during an informed consent process. George Isham then said that his impression is that many of the people attending the workshop are too close to this issue and are not seeing the forest for the trees. “I think one of the things that I have gotten from today is the fact that informed consent is really part of a larger patient education/patient decision-making framework. I don’t have, at the end of this day, a sense that we have a good logic model that encompasses all those things,” said Isham. He also wondered what Paasche-Orlow’s recommendations would look like if the field took a bigger view of this issue in terms of the kinds of things that could be done. “We need the smart people who are in this room to come to a working session where we would have white boards and stickies and get people working on processes and take advantage of their knowledge in a different kind of way to understand the issues and try to create solutions,” said Isham. He then added that he believes that problem lies with clinicians and institutional leaders who have created a culture that does not respect patient desires to the extent that it should.

Saag responded with the observation that what was missing from this workshop was the view of patients, particularly patients from different educational backgrounds and greater diversity in terms of ethnic and racial backgrounds and language skills. “That is the perspective that we need to bring in, particularly in the area of patient-centeredness,” said Saag. Paasche-Orlow remarked that he has seen too many projects on organizational change fail because of poor management or commitment or lack of resources. What is needed, he said, is for an organization to embrace an entire campaign, complete with marketing and infrastructure, for cultural change. He also noted that this change will take generations to complete.