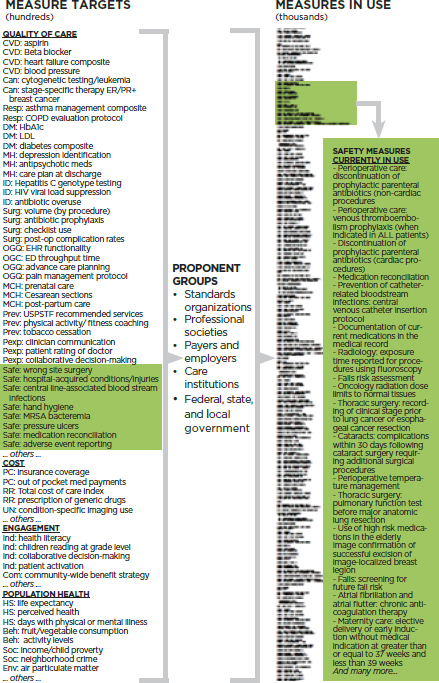

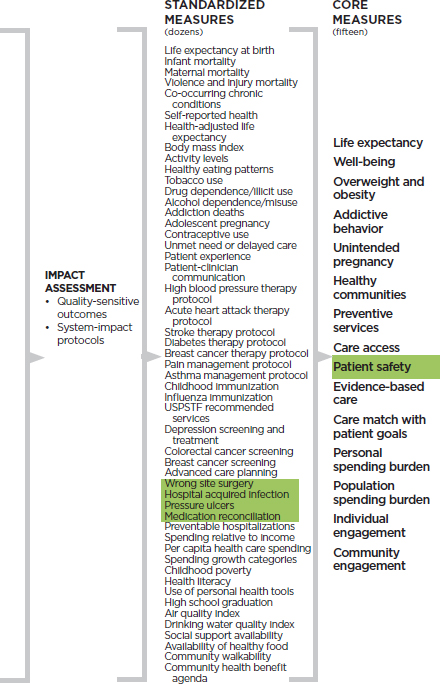

In identifying the core measure set, the Committee sought to balance the need for parsimony with the need for usability and applicability for a variety of stakeholders at different levels throughout the health system. This chapter describes the Committee’s process for and considerations in developing the core measure set; presents the core measure set; describes the rationale, supporting evidence, and current data availability for the set; and identifies provisional data indicators as the best available reflections of the current performance levels for each of the core measures, as well as related priority measures that various groups may wish to use to provide a more granular reflection of the current state for each of the core measures. The concluding section provides an overview of processes and approaches anticipated for developing, applying, and improving the core measures over time.

APPROACH TO IDENTIFYING THE CORE MEASURE SET

The Committee considered a broad range of issues and approaches for the process of identifying and evaluating candidate core measures and the qualities of the overall set. Key considerations included ensuring that the core set would address the most critical issues and elements of the American health system, as well as meet the Committee’s criteria for a core measure set presented in Chapter 3 (see Box 3-1), and choosing best current measures to be used until the processes could be set in motion to refine the measures needed for application at every level.

Addressing the Criteria for the Set

To ensure that the core measure set would be as relevant, useful, and effective as possible for a broad range of stakeholders, the Committee focused on identifying measures for the health influences, characteristics, and interventions that matter most in the domains of healthy people, quality of care, costs of care, and people’s engagement in health and health care. Furthermore, the Committee considered the potential core measurement needs, priorities, and challenges for key stakeholder groups, including patients, families, and the public; clinicians; health care organizations; payers and employers; public health agencies at multiple levels; regulatory authorities; grant-making organizations; and media. In addition to the evidence base for various candidate core measures, the Committee considered the potential utility of candidate measures as tools for motivating change, with particular attention to national health priorities, the face validity of measures, the strength of their linkage to progress, their capacity to promote broader change, their technical reliability, and their relevance at multiple levels of the health system.

These and other considerations were operationalized through the development of criteria for the core set, described in Chapter 3 (see Box 3-1). These criteria served as a tool for assessing the set of measures at various stages of development and ensuring that the final product of the Committee’s deliberations would accord with its intentions. At one point, for example, the Committee’s core set had expanded to include more than 50 measures, which upon consideration, the Committee concluded did not meet the criterion of parsimony. Similarly, the Committee considered various process measures, such as measures of screenings or interventions for specific conditions, throughout its deliberations. However, a core set consisting substantially of process measures would fail to meet the criterion of being outcomes-oriented. The Committee also chose not to focus the set on individual diseases because other candidate measures had greater potential to spur progress as well as utility at multiple levels while maintaining the principle of parsimony.

Addressing the Criteria for the Measures

As discussed in Chapter 3, building on lessons learned from previous core measure initiatives, the Committee also developed criteria to guide the selection of individual measures: the importance of the issue addressed by a measure, the strength of a measure’s linkage to progress, its face validity, its technical reliability as an indicator, its potential for broader system impact, and its utility at multiple levels (see Box 3-1). The Committee used these criteria to assess candidate measures on a three-point scale (meets criterion,

somewhat meets criterion, does not meet criterion), using the results of this process to guide changes and refinements. For example, while counseling on smoking cessation is an important clinical intervention for a particular addictive behavior, it does not meet the criterion of potential for broader system impact, as it is focused narrowly on a specific intervention within the care system. Similarly, it does not meet the criterion of strength of linkage to progress as cessation counseling alone, while supported by evidence of effectiveness, is unlikely to dramatically reduce smoking prevalence absent broader concerted efforts to address the social and cultural correlates of tobacco use and other addictions.

Choosing a Best Current Measure

The core measure set presented in Table 4-1 targets the most critical issues for making progress toward healthy people, better-quality care, lower costs, and engaged people. In many cases, these core measures will need to

TABLE 4-1 Core Measure Set

| Domain | Key Element | Core Measure Focus | Best Current Measure | Current National Performancea | |

| Healthy people | Length of life |  |

Life expectancy | Life expectancy at birth | 79-year life expectancy at birth |

| Quality of life |  |

Well-being | Self-reported health | 66% report being healthy | |

|

Overweight and obesity | Body mass index (BMI) | 69% of adults with BMI 25 or greater | ||

| Healthy behaviors |  |

Addictive behavior | Addiction death rate | 200 addiction deaths per 100,000 people age 15+ | |

|

Unintended pregnancy | Teen pregnancy rate | 27 births per 1,000 females aged 15 to 19 | ||

| Healthy social circumstances |  |

Healthy communities | High school graduation rate | 80% graduate in 4 years | |

| Domain | Key Element | Core Measure Focus | Best Current Measure | Current National Performancea | |

| Care quality | Prevention |  |

Preventive services | Childhood immunization rate | 68% of children vaccinated by age 3 |

| Access to care |  |

Care access | Unmet care need | 5% report unmet medical needs | |

| Safe care |  |

Patient safety | Hospital-acquired infection (HAI) rate | 1,700 HAIs per 100,000 hospital admissions | |

| Appropriate treatment |  |

Evidence-based care | Preventable hospitalization rate | 10,000 avoidable per 100,000 hospital admissions | |

| Person-centered care |  |

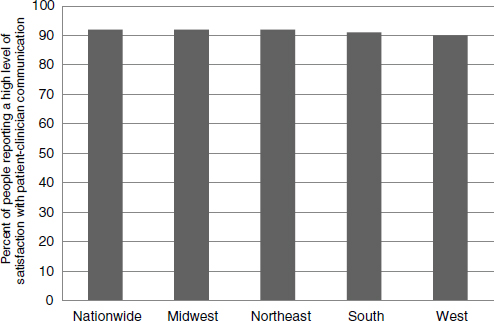

Care match with patient goals | Patient–clinician communication satisfaction | 92% satisfied with provider communication | |

| Care cost | Affordability |  |

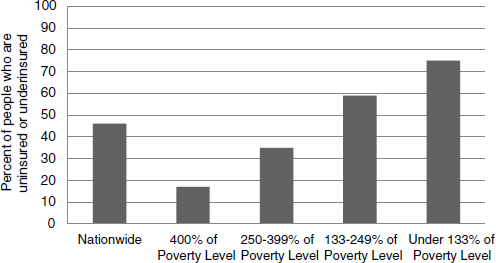

Personal spending burden | High spending relative to income | 46% spent >10% income on care, or uninsured in 2012 |

| Sustainability |  |

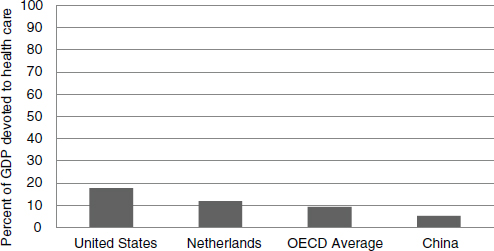

Population spending burden | Per capita expenditures on health care | $9,000 health care expenditure per capita | |

| Engaged people | Individual engagement |  |

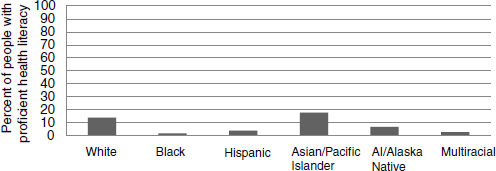

Individual engagement | Health literacy rate | 12% proficient health literacy |

| Community engagement |  |

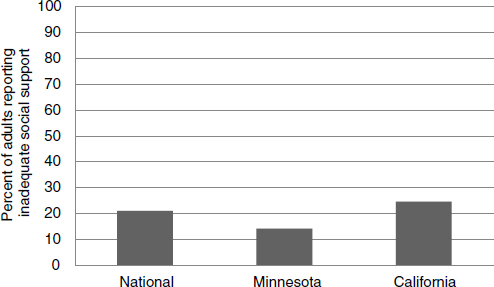

Community engagement | Social support | 21% inadequate social support | |

a See Table 4-2 for current performance sources and definition of terms.

be translated into specific, validated measures with associated data that can be applied at different levels for different groups, from the national or state level to the level of a single community or organization. Although the Committee recognizes the limitations of the data currently available for gauging multilevel performance on the issues addressed by the core measure set, it

believes that a reliable measure—single or composite—can be developed for each core measure focus identified. Further, including the measures in the core set can create the impetus to develop the data needed to calculate them.

In the face of current limitations, and until specific measures can be further tested and made available at multiple levels or new measures and composites are developed that better capture the full intent of the measure foci, the Committee has identified best current measures that provide a near-term reflection of the target issues and their associated outcomes and can be used to help operationalize the measure set now. For example, the core measure focus for appropriate treatment is evidence-based care. Because a high-quality composite measure for this indicator is not yet available, the Committee selected the preventable hospitalization rate as a best current measure. Although this measure has a number of limitations, including that it focuses exclusively on hospital care and is not pegged to specific guidelines or associated evidence, it does provide useful information about the health care system’s ability to provide appropriate treatment and evidence-based care. To illustrate how the core measures will be operationalized, the Committee developed an example set of national performance numbers for each of the best current measures. These figures for current national performance are presented for illustrative purposes and do not represent the Committee’s endorsement of the detailed measure specifications behind each number. While they may be imperfect in fully capturing the core measure foci, they are measures for which reliable data are available at the national level. (See Table 4-2 for national performance measures source material and definitions.)

Another important consideration was the selection of appropriate benchmarks for performance, although the identification of specific benchmarks or goals for the core measures was beyond the scope of the Committee’s charge. A key question here was whether there should be fixed benchmarks for national performance or benchmarks should be identified relative to an individual’s, organization’s, or community’s past performance. Fixed benchmarks would allow for direct comparisons of relative performance among groups, while relative benchmarks would incentivize improvement for all participants and would be less dependent on individual circumstances, variations in population characteristics, or geography. Relative benchmarks also could be helpful for individuals and organizations seeking to assess the success of their improvement efforts over time.

Overall, in selecting best current measures for the core measure foci, the Committee gave priority to those for which data are commonly used, available, and understood, and it attempted to adhere as closely as possible to the intent of each core measure and to ensure that the current measures selected would be readily understandable to a broad audience.

TABLE 4-2 Current National Performance on Best Current Measures, with Provisional Local and Institutional Sources

| Best Current Measure | National Performancea | Source | Yearb | Local Source (provisional) | HCO Source (provisional)c | ||

| Life expectancy at birth | 79-year life expectancy at birth | CDC VSSd | 2014 | VSS state data | Local data | ||

| Self-reported health | 66% report being healthye | CDC NHISf | 2013 | CHR,g BRFSS | Patient query | ||

| Body mass index (BMI) | 69% of adults with BMI of 25 or greaterh | CDC NHANESi | 2013 | CHR, NCCDPHP | Clinical records | ||

| Addiction death rate | 200 addiction deaths per 100,000 people aged 15+j | SG and VSSk | 2014 | VSS state data | Clinical records | ||

| Teen pregnancy rate | 27 per 1,000 females aged 15 to 19l | CDC VSS | 2014 | CHR, NCHS | Local birth data | ||

| High school graduation rate | 80% graduate in 4 yearsm | DOEd NCESn | 2014 | CHR, NCES | Local data | ||

| Childhood immunization rate | 68% of children vaccinated by age 3o | CDC NISp | 2012 | Local PH | Clinical records | ||

| Unmet care need reported | 5% report unmet medical needsq | CDC NHIS | 2014 | State estimates | State estimates | ||

| Hospital-acquired infection (HAI) | 1,700 HAIs per 100,000 hospital admissionsr | CDC HAI and AHRQ HCUPs | 2014 | CDC state data | Clinical records | ||

| Preventable hospitalization rate | 10,000 avoidable per 100,000 hospital admissionst | AHRQ HCUP | 2013 | CHR; HCUP | Clinical records | ||

| Patient–clinician communication | 92% report satisfactionu | CAHPSv | 2013 | Plans, providers | Patient query | ||

| High spending relative to income | 46% spent >10% of income on health or were uninsured in 2012w | CFx | 2012 | CF state data | Patient query | ||

| Per capita expenditures on health care | $9,000 per capitay | CMSz | 2013 | State spending | TCOC & RUaa | ||

| Health literacy rate | 12% with proficient health literacybb | DOEd NCES | 2006 | (not available) | (not available) | ||

| Social support | 21% inadequate social supportcc | CDC BRFSS | 2014 | CHR, BRFSS | Patient query | ||

a Rounded to nearest integer or nearest 1,000.

b Year refers to year published.

c HCO = health care organization.

d CDC VSS = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Vital Statistics System.

e Percent who report excellent or very good health.

f NHIS = National Health Interview Survey.

g CHR = County Health Rankings.

h Overweight defined as having a BMI of 25 or greater. Refers to BMI for adults 20 and older.

i NHANES = National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

j Computed. 2014 Surgeon General’s Report: The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress estimates 480,320 deaths among people 35 and older are attributable to smoking annually, 2005-2009. Add 39,030 drug-induced deaths among people 15 and older in 2009 and 24,515 alcohol-induced deaths among people 15 and older in 2009 (CDC Deaths: Final Data 2009). Summing these figures produced a total of 543,865 addiction-induced deaths in 2009 among people 15 and older. Given that there were 240,144,000 people 15 and older in 2009, this produced a rate of 226.5 addiction-induced deaths per 100,000 people 15 and older, which was rounded to 200 addiction deaths per 100,000 people 15 and older.

k SG = 2014 Surgeon General’s Report: The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress.

l Computed. In 2013, 274,641 babies were born to women 15-19 years old. This gives a live birth rate of 26.6 per 1,000, which was rounded to 27 per 1,000.

m Refers to public high school graduation rate.

n DOEd NCES = Department of Education National Center for Education Statistics.

o Refers to vaccination rate for children 19-35 months of age who receive combined series of recommended vaccines. Includes ≥4 doses of DTaP, ≥3 doses of poliovirus vaccine, ≥1 dose of measles vaccine, full series of Hib (3 or 4 doses, depending on product), ≥3 doses of HepB, ≥1 dose of varicella vaccine, and ≥4 doses of PCV.

p NIS = National Immunization Survey.

q Refers to the percent of people who failed to obtain needed medical care because of cost at some time during the past 12 months.

r Computed. Refers to patients in acute care hospitals with at least one health care–associated infection (http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1306801#t=articleTop). This total of 648,000 patients with HAIs was converted to a per 100,000 rate using data from the National Inpatient Survey (NIS), which estimates 39 million hospital stays in 2010. This yielded 1,662 HAIs per 100,000.

s CDC HAI = CDC Healthcare Associated Infection Prevalence Report; HCUP = Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project.

t Computed. HCUP reports 3.9 million preventable hospitalizations per year. This was converted to a per 100,000 rate using the HCUP 2010 National Inpatient Survey, which reports 39 million hospital stays per year. This yields a rate of 10,000 per 100,000.

u Refers to the percent of people reporting the highest level of satisfaction with their provider’s communication.

v Top box scores from Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) Clinician and Group Survey 2013.

w Refers to percent of adults who were uninsured or underinsured in 2012. Underinsured is defined as insured all year but experiencing either out-of-pocket expenses that were 10% or more of income; out-of-pocket expenses equaling 5% or more of income if low-income (less than 200% of poverty level); or deductibles equaling 5% or more of income.

x CF = The Commonwealth Fund.

y Refers to national health expenditures per person in 2013.

z CMS = Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

aa TCOC & RU: total cost of care and resource use.

bb Proficiency represents the highest level of literacy on the following scale: below basic, basic, intermediate, proficient.

cc Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) data as reported by the County Health Rankings for 2005-2011. Refers to inadequate social and family support.

The Committee anticipates the development of better measures over time, along with progress in the capacity for their use and impact.

If, on the one hand, single measures such as life expectancy and self-reported health status are too narrow to serve as a proxy for American health, and health care, and, on the other hand, there exist too many overlapping and uncoordinated measures to enable a ready assessment of the state of America’s health and health care, how can the right number of measures be identified? Because there is no definitive answer to that question, the Committee approached the issue by using a framework with the four domains in its charge—healthy people, quality of care, costs of care, and people’s engagement in health and health care—as a starting point. Within each domain, the Committee then pursued a consensus-based, iterative process for identifying the critical facets or “key elements” of each domain. Within each key element, the Committee then identified major foci for measurement and assessment, or “core measures.” A single core measure was identified for each key element. The exception to this pattern was healthy behaviors, for which, because of their distinctiveness and importance, the Committee identified three core measures. As discussed above, to facilitate near-term applicability, the Committee also identified a best current measure for each of the 15 core measures. These indicators represent how each core measure can, or could, be operationalized to provide practical information about the state of American health and health care.

Finally, the Committee identified an additional 39 “related priority measures” that, together with the core measures, give a more detailed view of the state of the nation’s health and health care and enhance the flexibility of core measures for application in diverse health stakeholder groups. While improving health is a shared goal across the health system, stakeholder groups have different foci for action and, therefore, may have priorities for measurement in certain areas.

These related priority measures, shown in Table 4-3, are sufficiently granular and specific to be actionable by stakeholders as needed for their particular circumstances. The Committee anticipates that these related measures would provide texture for those working with a particular emphasis in health and health care. For example, related priority measures could provide more actionable information for providers working in certain specialties, or for community activists who are focused on particular community health outcomes or issues. Given the broad nature of the core measure set, the related priority measures can increase the actionability of the set by providing a tool for different stakeholder groups to focus attention on particular areas.

TABLE 4-2 Core Measure Set with Related Priority Measures

| Core Measure Focus | Best Current Measures | Related Priority Measures | |

|

Life expectancy | Life expectancy at birth |

Infant mortality Maternal mortality Violence and injury mortality |

|

Well-being | Self-reported health |

Multiple chronic conditions Depression |

|

Overweight and obesity | Body mass index |

Activity levels Healthy eating patterns |

|

Addictive behavior | Addiction death rate |

Tobacco use Drug dependence/illicit use Alcohol dependence/misuse |

|

Unintended pregnancy | Teen pregnancy rate |

Contraceptive use |

|

Healthy communities | High school graduation rate |

Childhood poverty rate Childhood asthma Air quality index Drinking water quality index |

|

Preventive services | Childhood immunization rate |

Influenza immunizations Colorectal cancer screening Breast cancer screening |

|

Care access | Unmet care need |

Usual source of care Delay of needed care |

|

Patient safety | Hospital-acquired infection rate |

Wrong-site surgery Pressure ulcers Medication reconciliation |

|

Evidence-based care | Preventable hospitalization rate |

Cardiovascular risk reduction Hypertension control Diabetes control composite Heart attack therapy protocol Stroke therapy protocol Unnecessary care composite |

|

Care match with patient goals | Patient–clinician communication satisfaction |

Patient experience Shared decision making End-of-life/advanced care planning |

|

Personal spending burden | High spending relative to income |

Health care–related bankruptcies |

| Core Measure Focus | Best Current Measures | Related Priority Measures | |

|

Population spending burden | Per capita expenditures on health care |

Total cost of care Health care spending growth |

|

Individual engagement | Health literacy rate |

Involvement in health initiatives |

|

Community engagement | Social support |

Availability of healthy food Walkability Community health benefit agenda |

The Committee believes that the core measure set presented in Table 4-1 constitutes a set of the vital signs for assessing the state of the nation’s health and health care and progress in their improvement over time. The text that follows describes each core measure in turn—its importance, the best current measure for its focus, the related priority measures, and the disparities among population subgroups in that focus area.

|

Life Expectancy |

Importance

Life expectancy is a validated, readily available, and easily comprehensible indicator for a critical health concept—length of life—based on the simple logic that healthier people tend to live longer. Because life expectancy depends on a full range of individual and community influences on health—from cancer to homicide—it provides an inclusive, high-level indicator for health, broadly defined. Life expectancy also is useful comparatively across institutions, communities, states, regions, and nations as a means of quickly assessing relative health. Given its broad scope, moreover, life expectancy has significant potential to drive coordinated action toward health improvement. A reversal in life expectancy for a group, or an intractable or increasing disparity, is a fundamental and strong failure alert. Improving life expectancy for any group requires the engagement of a broad range of stakeholders working individually and in coordination to address the causes of premature death in the population as whole, as well as in key demographic subpopulations. For example, safer cars and roads

could reduce traffic fatalities; more effective community policing could reduce violent crime; increased investment in biomedical research could result in new therapies and interventions; and improved health literacy could lead to more people taking an active role in maintaining and improving their behavioral health. Thus, life expectancy is a sentinel and cross-cutting core measure for which a broad range of stakeholders are accountable.

Best Current Measure

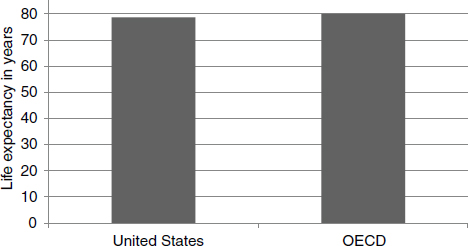

The Committee identified life expectancy at birth, as reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) Vital Statistics System, as the best current measure for life expectancy (CDC, 2015b). This measure encompasses deaths at all ages and from all causes and is a simple, reliable, accessible, and routinely utilized barometer for the overall health of a population. Data for this measure have been collected by the U.S. government for more than 100 years (Glover, 1921). The CDC reports life expectancy estimates annually, including estimates for different demographic groups. The data used to create these life expectancy estimates are collected and reported at the county level, such that data in the CDC Vital Statistics System can be used for more granular estimates of county, state, and regional life expectancy. Life expectancy also is an important indicator of the relative performance of the United States among peer countries. While the average life expectancy at birth for the OECD countries was 80.1 years in 2011, American life expectancy was 78.7 years (see Figure 4-1), 4.1 years less than citizens could expect to live in Switzerland, the leader in life expectancy (OECD, 2013).

It should be noted that life expectancy at birth has limitations as a best current measure for life expectancy, including issues of representativeness. For example, life expectancy alone provides little information on specific causes of or potential solutions for health challenges; more specific measures of mortality for specific causes or groups can be useful in developing interventions or solutions aimed at improving life expectancy. The usefulness of life expectancy may also be limited for small groups or groups including only young people in whom the number of deaths is low. Additionally, because life expectancy includes infant mortality, these deaths may have a large effect on the average.

While significant additional measure development is needed for the majority of the core measures, life expectancy at birth is an example of a best current measure that is sufficiently valid and reliable to represent the core measure concept. However, additional development in the measurement of life expectancy may produce more innovative approaches to both measuring and presenting information about length of life.

FIGURE 4-1 Life expectancy at birth: United States versus OECD countries.

SOURCE: OECD, 2013.

Related Priority Measures

Alternative measures considered by the Committee include life expectancy at various ages, infant mortality, maternal mortality, quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), health-adjusted life years (HALYs), and mortality due to violence and injury. Each of these measures provides important information about a key factor in the population’s health. These measures generally are more granular than life expectancy at birth, and they provide additional information about significant causes of shorter life expectancies in the United States. Among them, the Committee selected three related priority measures for the life expectancy core measure: infant mortality, maternal mortality, and mortality due to violence and injury. Each of the issues addressed by these measures is important to improving life expectancy in the United States, and each may be useful for stakeholder groups focused on particular aspects of length of life. For example, a community organization with a particular focus on preventing violence would use mortality due to violence and injury to provide additional insights to serve its particular mission.

Disparities

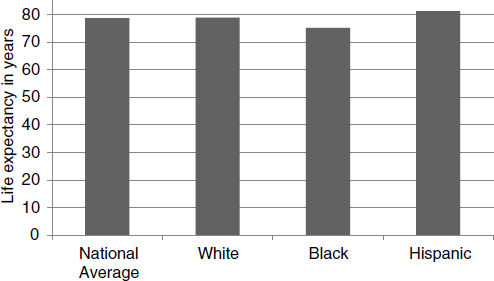

Life expectancy reveals disparities in overall health outcomes for demographic and socioeconomic groups, as well as for geographic regions. While life expectancy for the white population is 78.9 years, it is 75.1 years for the black population and 81.2 years for the Hispanic population (Murphy et al., 2013) (see Figure 4-2). In Mississippi, life expectancy among African

FIGURE 4-2 Disparities in U.S. life expectancy at birth.

SOURCES: Murphy et al., 2013; OECD, 2013.

Americans is 72.4 years, while white residents of that state live 76.1 years (CDC Vital Statistics Cooperative Program, 2010). Moreover, life expectancy for women generally is longer than for men—81.0 years versus 76.2 years (Murphy et al., 2013).

|

Well-being |

Importance

Life expectancy and death rates from various diseases and injuries provide clear measures of health in a population group, but health and well-being in the population have many other components, including illness from chronic or acute diseases, injury, functional capacity, mental health, sense of security, and social networks. As the World Health Organization notes, “Health is a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” (WHO, 1946). The health of an individual has both objective and subjective dimensions. In fact, people’s perception of their own health not only is an indication of well-being but is often a predictor of utilization of and satisfaction with health care.

An estimated 84 percent of health care spending in the United States is attributable to chronic diseases, which affect approximately half of the adult population (RWJF, 2010). Closely linked to many of these chronic diseases are a variety of health risk behaviors. For example, approximately half of adults do not get sufficient aerobic exercise, and approximately three-quarters of adults fall short of recommendations for regular muscle-strengthening physical activity (CDC, 2012c). And approximately 23 percent of adults report eating vegetables less than once per day (CDC, 2013c). Chronic diseases are associated with significant disabilities, which negatively impact well-being and life expectancy, among other health factors. For example, approximately half of adults with disabilities report no physical activity, and they are more likely to have one or more chronic diseases relative to adults with disabilities who do report physical activity (Carroll et al., 2014).

Well-being is a measure with the capacity to drive action among a broad range of stakeholder groups, as it encompasses a large number of potential causal factors, from poverty to depression to chronic disease. Improving well-being across the nation will require collective action, extending well beyond the care system to include such groups as employers, schools, community organizations, and others.

Best Current Measure

The Committee identified self-reported health status as the best current measure for well-being. It is a uniquely broad and accessible measure that encompasses such factors as mental health, disability, and reproductive health, among others, in a simple manner that needs no explanation. The use of self-reported health status as a measure of health emerged in the early 1980s, prompted by the publication of the Manitoba Longitudinal Study, which found that self-reported health status was a stronger predictor of health outcomes than medical records or self-reports of medical conditions (Mossey and Shapiro, 1982). Self-reported health status has been shown to be an independent predictor of life expectancy and a reliable measure for health and wellness in the United States (Idler and Benyamini, 1997). People who self-report that their health is poor have a mortality risk twice as high as that of people who report excellent health (DeSalvo et al., 2006). Self-reported health also has been shown to be a useful predictor for expenditures (DeSalvo et al., 2009).

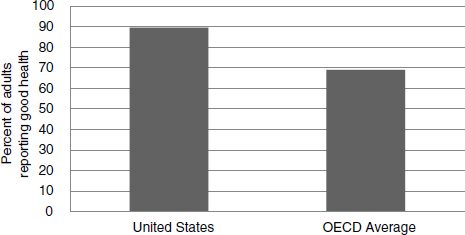

Data on self-reported health status are collected annually through the CDC’s National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). In 2014, 66.2 percent of people reported that they were in excellent or very good health (Ward et al., 2014). The NHIS also provides estimates of self-reported health status for subpopulations, including by gender, race, and ethnicity. Data on

FIGURE 4-3 Adults self-reporting good health: United States versus OECD countries.

SOURCE: OECD, 2013.

self-reported health status also are available at more granular geographic levels from various other sources. Figure 4-3 shows a comparison of the percentage of adults reporting good health in the United States and the OECD countries.

A potential limitation of self-reported health status is that it may reflect cultural factors not directly dependent on health, such that some subpopulations may score systematically lower because of differing cultural concepts and definitions of what it means to be healthy (Shetterly et al., 1996). This limitation may also affect comparability on an international scale, although self-reported health is used as a health indicator by the World Health Organization and the OECD.

While self-reported health status is a powerful tool for assessing well-being in terms of both its statistical validity and its conceptual simplicity, additional measure development may lead to improvements. For example, some survey structures may be superior to others for assessing well-being, so that improvements in the structure and wording of survey questions could lead to more accurate measures. There may also be novel solutions to incorporating self-reported health into electronic health records, such that data could be gathered and aggregated from the individual level rather than through a traditional survey mechanism.

Related Priority Measures

Alternative measures considered by the Committee include functional status, healthy days, QALYs or HALYs, mental health, and reproductive health. While each of these measures provides valuable information about aspects of well-being, many of these other measures provide additional, more detailed information about different aspects of well-being. Among them, the Committee selected two related priority measures for well-being: multiple chronic conditions and depression. These two measures provide information about well-being from two critical perspectives for the nation’s health: chronic disease and mental health. An estimated 117 million Americans, or half of the U.S. population, have at least one chronic disease, and these conditions account for an estimated 86 percent of health care dollars (CDC, 2015a; Ward and Schiller, 2013). An estimated 25 percent of Americans have a mental illness, and the economic burden of mental illness was estimated at $300 billion in 2002 (Reeves et al., 2011).

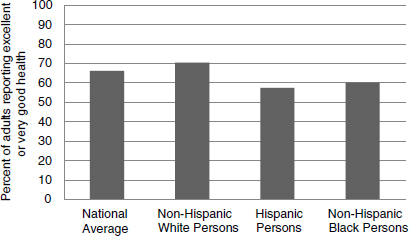

Disparities

Self-reported health status shows disparities across certain demographic groups (see Figure 4-4). For example, 70.5 percent of non-Hispanic whites report excellent or very good health, compared with 58 percent for Hispanics, 60.1 percent for non-Hispanic blacks, and 66 percent for the population at large (CDC, 2013a). Data also suggest that men are more likely than women to report having excellent health, while women are more likely than men to report that their health is fair (CDC, 2013a). Moreover, the percentage of people reporting excellent or very good health tends to decrease with

FIGURE 4-4 Disparities in U.S. self-reported health status.

SOURCE: CDC, 2013a.

age, from 84 percent for people under age 18, to 64 percent for those aged 18-64, to 45 percent for those aged 65 and older (CDC, 2013a).

|

Overweight and Obesity |

Importance

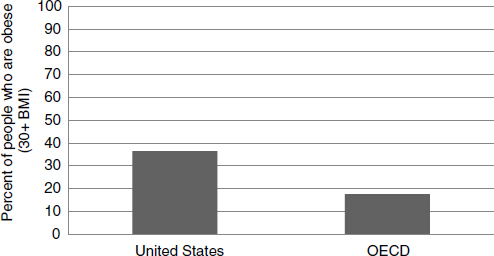

An estimated 35 percent of U.S. adults and 17 percent of U.S. children and adolescents are obese (Ogden et al., 2014). Obesity accounts for an estimated $147 billion annually in medical costs, and people who are obese have annual individual medical costs estimated to be $1,429 higher than those of people who are not obese (Finkelstein et al., 2009). The increasing rates of overweight and obesity among U.S. adults and children are associated with numerous health conditions, including hypertension, coronary heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and stroke. Figure 4-5 shows a comparison of the prevalence of obesity in the United States and the OECD countries.

Overweight and obesity presents a significant challenge for American health. It is a feature of American life with causes and consequences that extend beyond the scope of the health system, including socioeconomic, cultural, and lifestyle factors, in particular diet and physical activity, which together constitute leading causes of early death. Therefore, reducing the prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States—and, by

FIGURE 4-5 Obesity prevalence: United States versus OECD countries.

NOTE: BMI = body mass index.

SOURCE: OECD, 2013.

extension, improving health and reducing care costs across the nation—will depend on the coordinated efforts of many stakeholder groups.

Best Current Measure

Body mass index (BMI), a relative number derived from an individual’s weight and height, serves as a reliable indicator of overweight and obesity. The Committee therefore identified BMI as the best current measure for this core measure focus.

Data on BMI are collected annually by the CDC through the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), and they are also available through a variety of other sources and at various levels. In 2012, an estimated 69 percent of U.S. adults were overweight or obese, which is defined as having a BMI of 25 or greater (CDC, 2013b). The CDC NHANES data provide estimates for different subpopulations by age, gender, and race and ethnicity. Calculating this weight/height ratio is easy and inexpensive in both the care and the home settings, allowing for quick comparisons of weight status among individuals, groups, and the public. The BMI scale marks the relationship between weight and obesity-related disease and death.

Because of the ease of measurement and high standardization, BMI is the most common method for assessing obesity and screening for associated health risks. The CDC uses BMI as its primary measure to determine overweight and obesity among the general population. BMI calculation, used primarily as a screening tool, can be followed by more detailed diagnostic tests to fully assess health risk. BMI can be calculated personally with the aid of online BMI charts, and because of its ease of applicability it can be a tool for motivating change.

While the BMI ratio does not measure body fat directly, research has shown that it is strongly correlated with more direct measures of body fat (Mei et al., 2002). Although the correlation between BMI and body fat percentage is strong, this correlation differs, however, according to gender, age, and race, largely because BMI does not distinguish between body fat and lean body mass. At a constant BMI ratio, for example, women are likely to have more body fat than men, and older adults are likely to have more body fat than younger adults. In addition, research has indicated differences in health risks across ethnicities at the same BMI. Studies have found that blacks have a leaner muscle mass and thus lower body fat than whites, suggesting that blacks are at a lower risk of obesity-related health issues than whites with the same BMI ratio (Rush et al., 2007). However, the incidence of obesity is higher in non-Hispanic blacks in the United States than in non-Hispanic whites, so overall, the former are still more susceptible to obesity-related health issues than the latter (Flegal et al., 2012).

Better measures for overweight and obesity may be developed in the future. For example, while BMI data are relatively easy to collect and calculate based on weight and height, more precise measurements based on percent body fat or other features may become feasible with improvements in data and measurement.

Related Priority Measures

Alternative measures considered by the Committee include caloric intake, fruit and vegetable consumption, sedentary lifestyles, and activity levels. Each of these measures provides important information about a key component of overweight and obesity. Among them, the Committee selected two related priority measures for overweight and obesity that provide a more granular view of two major elements of excess body fat: excessive caloric input and insufficient caloric output. Activity levels and healthy eating patterns focus on these two critical factors in overweight and obesity, and they are closely linked to the shifts in behavior that matter most for reducing overweight and obesity nationwide.

Disparities

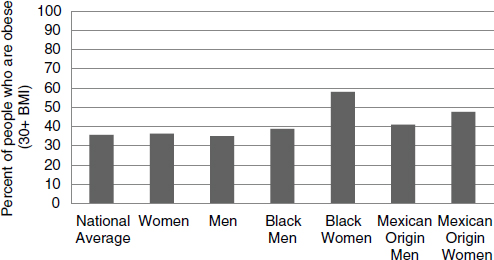

The BMI ratio underscores disparities in health outcomes for racial and socioeconomic groups, as well as a regional divide in overweight and obesity statistics across the nation. For instance, 83 percent of males of Mexican origin are overweight or obese, while 69 percent of adults aged 20 and over are classified as overweight or obese in the general U.S. population (NCHS, 2014). From 2009 to 2012, 36 percent of the general U.S. population was obese or had a BMI greater than or equal to 30. Obesity was slightly more common among women, at 36 percent, than among men, at 35 percent. Black men and women had obesity rates of 39 and 58 percent, respectively. Among people of Mexican origin, 41 percent of males and 48 percent of females were obese (NCHS, 2014) (see Figure 4-6).

|

Addictive Behavior |

Importance

Addiction and addictive behavior represent a significant and complex challenge for the health system, as well as for communities and families. Approximately 19 percent of American adults smoke, 17 percent of adults

FIGURE 4-6 Disparities in obesity prevalence.

NOTE: BMI = body mass index.

SOURCE: NCHS, 2014.

binge drink, and an estimated 9 percent of people aged 12 years and older were found to have used an illicit drug within the past month (CDC, 2011, 2012b; NCHS, 2014). Increasingly, misuse of prescription drugs contributes to premature death. The estimated economic cost of substance abuse and addiction in the United States is $559 billion per year (NIDA, 2008).

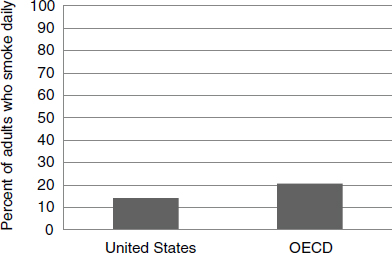

Smoking persists as a significant cause of poor health despite decades of scientific evidence for its contributions to morbidity and mortality, as well as governmental and public health efforts to counter both smoking behavior and its biological effects (HHS, 2014a). Figure 4-7 shows a comparison of the percentage of adults who smoke daily in the United States and the OECD countries. Today, tobacco use is considered the leading cause of preventable morbidity and mortality in the United States (CDC, 2011). The most recent estimate available from the CDC suggests that between 2005 and 2009, 480,320 deaths were attributable to smoking each year, including deaths from cancer, cardiovascular and metabolic diseases, respiratory conditions, perinatal conditions, and secondhand smoke (HHS, 2014a). It is estimated that smokers live an average of 11 to 12 fewer years than nonsmokers (HHS, 2014a).

Addiction and misuse of alcohol and drugs also present a central challenge for the health and health care of Americans. And the broad family and social impacts of addiction to alcohol and other drugs may well exceed the consequential impacts of tobacco use.

FIGURE 4-7 Smoking behavior. Percentage of adults who smoke daily: United States versus OECD average.

SOURCE: OECD, 2013.

All addictions are shaped by a range of biological, social, and cultural factors, and progress in preventing, mitigating, and managing the health impacts of addiction depends on the coordinated actions of multiple stakeholders beyond health care, including policy makers, scientific researchers, schools, law enforcement, families, and other community stakeholders. The success of counteradvertising, taxation, and labeling in reducing tobacco use stands as an important testament to this fact, as do other successes related to alcohol and drug use (Hammond et al., 2003).

Best Current Measure

The Committee identified the addiction death rate as the best current measure for addictive behavior. Data on mortality due to addictive behavior come from a variety of sources, including the CDC Vital Statistics System, which reports data on the numbers and rates of death associated with individual International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 codes. Summing the CDC estimates for contributions from tobacco, alcohol, and drugs, the Committee computed an approximate best estimate of 200 addiction-related deaths per 100,000 people aged 15 and older (see Table 4-2). It should be emphasized both that this is a rough approximation, derived from different sources, and that the methodology will need substantial work if it is to be available on an annual basis and computable at multiple levels.

Related Priority Measures

Alternative measures considered by the Committee include rates of smoking, excessive alcohol use, and illicit drug use. While deaths due to addictive behavior provide an aggregate view of U.S. mortality across these three addiction categories, the Committee selected three related priority measures that reflect these categories for use by stakeholder groups that may need a more detailed view of the behaviors associated with addiction-related mortality: tobacco use, drug use, and excessive drinking. For example, some communities may have smoking rates that are lower than average but a significantly higher incidence of drug use. For such communities, the use of a measure of drug use can provide more actionable information than the aggregate current best measure.

Disparities

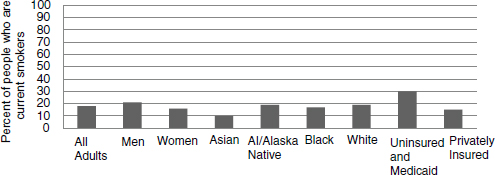

Data on addiction-related mortality highlight significant disparities in health and mortality across groups defined by geography, race/ethnicity, gender, and socioeconomic status (see Figure 4-8). For example, it is estimated that 138 deaths per 100,000 population are attributable to smoking in Utah, while the estimated rate in Kentucky is 371 per 100,000. In terms of gender, the CDC estimates that 16 percent of women are current smokers, compared with 21 percent of men. Among racial/ethnic groups, smoking rates are lowest among Asian adults (10 percent), and are higher for American Indian or Alaska Native adults (19 percent), white adults (19 percent), and black adults (17 percent). Additionally, the percentage of current smokers under age 65 is twice as high within both the uninsured

FIGURE 4-8 Current smokers by demographic group.

NOTE: AI = American Indian.

SOURCE: Blackwell et al., 2014.

and Medicaid populations (30 percent) relative to the privately insured population (15 percent) (Blackwell et al., 2014).

|

Unintended Pregnancy |

Importance

Unintended pregnancy presents a significant challenge for both individual and community health. According to a report from the CDC’s Division of Vital Statistics, it is the most direct available measure of women’s ability to choose the number and timing of their pregnancies. As such, it is a measure that aggregates a variety of social, behavioral, cultural, and health factors, particularly the availability and use of both knowledge and tools for family planning.

In 2010, an estimated 37 percent of births in the United States were unintended at the time of conception—a figure that had not declined significantly since 1982 (Mosher et al., 2012). The literature on unintended pregnancy shows that infants and children whose births were unintended by the mother have a variety of elevated risks, including adverse social, economic, and health outcomes. Factors implicated in these increased risks include delayed prenatal care, smoking during pregnancy, not breastfeeding the baby, poorer childhood health, and poorer outcomes for both the mother and the mother–child relationship (Mosher et al., 2012). The results of longitudinal studies following the children of unintended pregnancies into adulthood also have found poor long-term social and health outcomes (David, 2006). Making national progress in reducing unintended pregnancy will depend on a network of stakeholders at different levels, as the drivers and consequences of unintended pregnancy reach across the boundaries of the care system to include cultural factors and institutions, education, care access, and healthy behaviors.

Best Current Measure

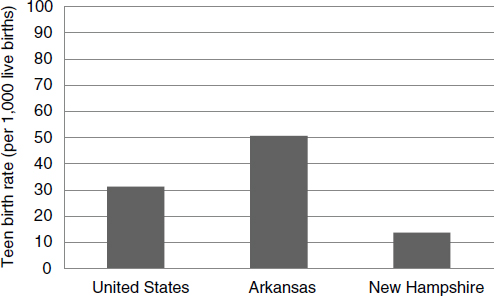

The Committee identified teen pregnancy rate as the best current measure for unintended pregnancy. The number of live births to women aged 15 to 19 is readily countable, and it presents an accessible view of the extent to which births in the United States are planned and, by extension, the variety of social, cultural, educational, and health care factors related to the behaviors associated with unintended pregnancy. The data come from the CDC’s Vital Statistics System, which reports birth data annually. In 2012, the live

birth rate for women aged 15-19 was 26.6 per 1,000, or a total of 274,641 babies born to women in this age group (see Figure 4-9) (Hamilton et al., 2013). The rate of teen pregnancy has been declining over the last decade, with 2012 representing a record low. The cause of this decline is unknown, but it may be related to lower levels of sexual activity in this age group, as well as greater use of birth control. Teen pregnancy was estimated to cost U.S. taxpayers $9.4 billion in 2010 as a result of elevated health care and foster care costs, as well as increased incarceration rates and lower income among the children of teen mothers (The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy, 2013). This last deficit is related to high school dropout rates for teen mothers. The children of teen mothers also experience poorer health outcomes relative to the children of older mothers.

While teen pregnancy offers a look at unintended pregnancy in the population of women aged 15 to 19, better measures are needed to provide a full assessment of unintended pregnancy across age groups. For example, the CDC’s National Survey of Family Growth found that 23 percent of teen pregnancies were intended at conception, indicating that teen pregnancy is an imperfect proxy for unintended pregnancy (Mosher et al., 2012). Thus, as stronger measures are developed, teen pregnancy could be replaced by a more inclusive and precise measure of unintended pregnancy.

FIGURE 4-9 Teen pregnancy (aged 15-19 years): National average, worst-performing state, best-performing state.

SOURCE: Martin et al., 2013.

Related Priority Measures

Alternative measures considered by the Committee include family planning, contraceptive use, prenatal care, and low birth weight. Among these, the Committee selected contraceptive use as a related priority measure for unintended pregnancy. While teen pregnancy highlights a critical outcome related to contraceptive use, it also is more narrowly focused as it considers only women aged 15 to 19. The related priority measure of contraceptive use considers unintended pregnancy at any age, and could be useful for stakeholder groups that work with older populations or with a broader focus on women’s health and health care.

Disparities

While teen pregnancy rates have declined over the past decade across all demographic groups, disparities persist in the rates for some racial and ethnic minorities. As illustrated in Figure 4-10, in 2013 the teen pregnancy rate was 39 per 1,000 live births for non-Hispanic blacks, 42 for Hispanics, 31 for American Indians/Alaska Natives, 19 for non-Hispanic whites, and 9 for Asians/Pacific Islanders (Hamilton et al., 2014).

FIGURE 4-10 Teen pregnancy (aged 15-19) by race/ethnicity.

NOTE: AI = American Indian.

SOURCE: Hamilton et al., 2014.

|

Healthy Communities |

Importance

Individual health is a function of a wide range of socioeconomic and community factors, ranging from environmental quality to infrastructure to social connections. Thus, our health is closely tied to our communities, and, just as individual actions to improve health can benefit the community, community actions to improve health can benefit each individual member. Community health encompasses critical elements of health that fall outside of the care system but have a major impact on care and health outcomes, such as education, employment, housing, and environment.

Best Current Measure

The Committee identified high school graduation rate as the best current measure for healthy communities. An estimated 80 percent of high school students graduate in 4 years (DOEd, 2014). Selecting a single indicator to represent the range of factors involved in community health presents a measurement challenge. The Committee discussed the possibility of a community needs composite measure or index that would combine the full range of socioeconomic, cultural, and community factors impacting health into a single, accessible measure. While a variety of promising measures of this sort exist, including the Rockefeller Institute’s Economic Hardship Index or Dignity Health’s Community Need Index, the Committee concluded that additional work would be needed to develop a reliable composite measure of community health. For the near term, the Committee suggests high school graduation rate as a best current measure for general community health. Education level is certainly one of the strongest predictors of health, associated with a range of improved health outcomes, including length and quality of life.

Among the elements typically measured to assess socioeconomic status—education, income, and occupation, or a composite thereof—education appears to be the strongest and most consistent socioeconomic status predictor of good health (Winkleby et al., 1992). While the effect of education on health is due in part to the education itself, educational attainment measures, such as high school graduation rate, also are correlated with poverty and socioeconomic status both before and after graduation. People who graduate from high school tend to have higher incomes than those who do not, and higher income can lead to improved access to care

as well as better quality of life. These effects can span generations, with children of educated parents being more likely to attain a quality education than children of parents with low educational attainment. While high school graduation rate falls short of encompassing the full range of community health factors, it is a useful, accessible proxy for assessing socioeconomic status and community quality in the short term.

Unemployment and poverty were also considered as potential candidates for the best current measure for community health, and the Committee believes that a composite measure for community health would likely include all of these elements. Although unemployment and poverty might provide more immediate measures of community health, and effects on education are likely to occur over a longer time period, the Committee considered it important to highlight education as a critical factor in community health and socioeconomic well-being and a major determinant of health. This was due in part to the conclusion that elements of socioeconomic status linked to income are demonstrated in other areas of the core measure set, particularly within “personal spending burden.” Findings in the literature suggest that the correlation between income and education is not strong enough to justify using one as a proxy for the other and that, in some cases, education may be the best single socioeconomic predictor of good health (Braveman et al., 2005; Winkleby et al., 1992). Further, high school graduation rate serves to highlight the important role of stakeholder groups not traditionally considered to be part of the health system.

Data on high school graduation rates are available from a variety of sources, including the National Center for Education Statistics, and have been collected annually by the federal government since 1870 (Snyder, 1993). Graduation rate data also are available at many levels—from individual schools to counties to states—and can be readily parsed by gender, race, and ethnicity.

Improving high school graduation rates and, by extension, the health of communities will require coordinated efforts from a broad range of stakeholder groups both within and outside of the health system. For example, one study found that a 10 percentage point increase in Medicaid eligibility among children resulted in a 5 percent decline in a state’s high school dropout rate (Cohodes et al., 2014). This finding suggests that increasing access to health care may enable more students to complete high school and, by extension, have higher incomes and make greater contributions to the economy throughout their lives.

While the Committee considers high school graduation rate to be the best current measure for community health, it could be replaced in the near term with a high-quality composite incorporating several of the most critical elements of community health. A preliminary composite measure for healthy communities might include education, air quality, walkability,

socioeconomic status, and access to healthy food. Developing composites for this and other measures where data currently are lacking is a priority for the implementation of core measures.

Related Priority Measures

Alternative measures considered by the Committee include environmental quality, poverty, quality of life, employment, and infrastructure. While many of these measures provide important information about a key aspect of community health, the Committee selected childhood poverty rate, childhood asthma, and air quality index as related priority measures. These three measures may be useful to certain stakeholder groups by illuminating additional facets of community health. For example, some communities may have particular challenges with air quality relative to other communities, such that assessing environmental health would increase the actionability of core measures for that community.

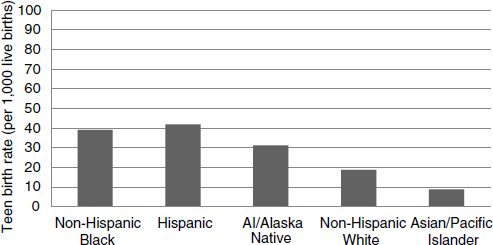

Disparities

As indicated by the high school graduation rate measure, 67 percent of American Indian/Alaska Native public high students graduate in 4 years, compared with 80 percent of public high school students across the country (DOEd, 2014). This statistical difference exemplifies the socioeconomic, racial, and regional disparities illuminated by the graduation rate measure (see Figure 4-11). During the 2011-2012 school year, 85 percent of female

FIGURE 4-11 Disparities in percentage of public high school freshman who graduate in 4 years.

NOTE: AI = American Indian.

SOURCE: Stetser and Stillwell, 2014.

students graduated within 4 years, compared with 78 percent of male students. Graduation rates also varied by race and ethnicity, with data reported for the following groups: American Indian/Alaska Native (68 percent), Asian/Pacific Islander (93 percent), Hispanic (76 percent), black (68 percent), and white (85 percent) (Stetser and Stillwell, 2014).

|

Preventive Services |

Importance

Appropriate use of clinical preventive services—immunization, counseling, and chemo prophylaxis—is important to improving health status and outcomes as well as efficiency in the delivery of care. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends a range of services for different groups, from hearing loss screening for infants to tobacco cessation counseling for current smokers (USPSTF, 2010).

Spending on health care in the United States is focused disproportionately on treatment of disease. While more than 75 percent of U.S. health care expenditures is related to the treatment of preventable conditions, only an estimated 3 percent is devoted to prevention and public health improvement activities (IOM, 2012b). The 2012 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report For the Public’s Health: Investing in a Healthier Future recommends that Congress double federal appropriations for public health in the interest of delivering a minimum package of public health services in every community nationwide (IOM, 2012b).

Increasing the coverage rate for preventive services is a goal that could bring together a broad range of stakeholder groups. While clinicians and public health stakeholders play a role in the direct provision of these services, education and outreach are critical to ensuring that people are both aware of the preventive services they need and readily able to access those services. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) may have a significant impact on this core measure focus as it requires coverage without copays or deductibles for all USPSTF-recommended preventive services. Community actors such as employers, public schools, and religious organizations could play a critical role in connecting people with public health resources and eliminating the barriers that keep people from receiving recommended preventive services.

Best Current Measure

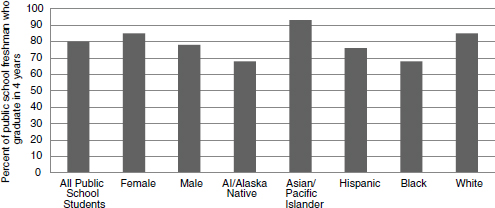

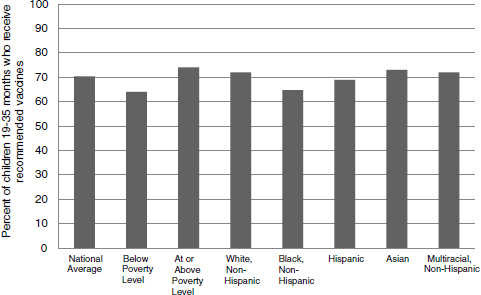

The Committee identified childhood immunization rate as the best current measure for preventive services. According to the CDC’s National

Immunization Survey, 68.4 percent of children aged 19-35 months received the combined series of recommended vaccinations in 2012 (CDC, 2012a). (The combined series includes at least 4 doses of DTaP, at least 3 doses of poliovirus vaccine, at least 1 dose of measles vaccine, the full series of Hib [3 or 4 doses, depending on the product], at least 3 doses of HepB, at least 1 dose of varicella vaccine, and at least 4 doses of PCV.) The Committee discussed the need for a composite measure that would express the extent to which people receive recommended preventive services. However, there is currently no high-quality measure that meets the Committee’s criteria. For the short term, the Committee proposes immunization status as a proxy for preventive services because it represents a particularly stable and long-lasting component of prevention and covers a broad non-disease-specific population. Immunizations have been shown to be among the most powerful preventive services in terms of their impact on both disease burden and costs. Data for this measure also are reliable. The CDC has collected data on immunization status annually since 1994 through the National Immunization Survey. These data provide estimates at the national and state levels and for selected urban areas (CDC, 2014d).

Whereas childhood immunization status provides a useful current window into preventive services by focusing on a single critical set of services, better measures may be developed in the future to assess the extent to which people receive the full range of recommended preventive services. Such a measure could take the form of a binary—the percentage of people receiving or not receiving recommended services—or an index, which would be used to assess the extent to which preventive services are received throughout the population. Developing composites for this and other measures where current data are lacking is a priority for the implementation of core metrics.

Related Priority Measures

Alternative measures considered by the Committee include the incidence of vaccine-preventable disease, colorectal cancer screening, aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease, breast cancer screening, tobacco cessation counseling, BMI screening and follow-up, and control of high blood pressure. While each of these measures provides important information about a key component of prevention, immunization status was selected as a proxy because it represents a particularly stable and long-lasting component of prevention and covers a large, non-disease-specific population. In addition to childhood immunization, the Committee identified three related priority measures for preventive services: influenza immunization, colorectal cancer screening, and breast cancer screening. While screening for many additional cancers are included in the USPSTF recommendations for preventive services, the Committee chose to highlight colorectal and breast cancer because they are associated with the highest rates of mortality other than lung cancer, which is included as a component of the core measure for addictive behavior (American Cancer Society, 2014).

FIGURE 4-12 Disparities in percentage of children aged 19-35 months who received recommended vaccines, 2012.

SOURCE: CDC, 2012a.

Disparities

The immunization status measure highlights disparities in health outcomes across demographic groups, particularly within socioeconomic subgroups (see Figure 4-12). In 2012, recommended vaccines were received by 64 percent of children aged 19-35 months living below the federal poverty level, compared with 70 percent of children of this age in the U.S. population at large (CDC, 2014d) and 74 percent of those at or above the poverty level (CDC, 2012a). Childhood vaccine coverage, as reported by the CDC, is estimated at 72 percent for non-Hispanic white children, 65 percent of non-Hispanic black children, 69 percent of Hispanic children, 73 percent of Asian children, and 72 percent of non-Hispanic multiracial children.

|

Care Access |

Importance

The ability to receive care when needed is a critical precondition for effective system performance. Unmet need for health care may occur for a variety of reasons, including lack of or insufficient health insurance, clinician shortages, lack of transportation, language barriers, insufficient health literacy, and physical limitations. Regardless of the reason, the avoidance or lack of needed care has a negative impact on health and may result in the deferral of treatment until a condition becomes more serious as well as in higher costs for both individuals and the health system.

Unmet need for medical care is a challenge that could be addressed with a variety of approaches and by a range of stakeholders. While the ACA increased access to health insurance by establishing insurance exchanges and expanding eligibility for Medicaid, millions of Americans still lack insurance coverage, a significant challenge for meeting the medical needs of the full population. Further, some areas of the country may have insufficient health care resources and staffing such that people are unable to receive timely appointments or lack the physical ability or transportation to reach a medical facility.

Best Current Measure

The Committee identified unmet care need as the best current measure for care access. Data on unmet care need are collected through a variety of measures and surveys, including the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s (AHRQ’s) Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, which was initiated in 1996 (AHRQ, 2009), and the NHIS. The NHIS unmet need survey instrument assesses inability or delay in receiving needed medical care, dental care, or prescription medications, and it considers affordability and lack of sufficient insurance as potential causes. A variety of other survey mechanisms, including the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) Clinician and Group survey, collect data on various aspects of access to care and unmet medical need. In addition, the data on unmet care need can be stratified by different geographic, demographic, and socioeconomic subpopulations, enabling comparisons for populations of interest. According to the NHIS, for January-June 2014, an estimated 5.4 percent of the population failed to obtain needed medical care because of cost at some point during the past 12 months (CDC, 2014a).

Access to care is an area in which significant change is under way as a result of the enactment and implementation of the ACA, which expanded access to other care resources in addition to insurance and placed limits on out-of-pocket spending. As the impact of these changes unfolds, new measures may need to be developed to accord with the evolving landscape of what access means in the context of the American care system.

Related Priority Measures

Alternative measures considered by the Committee include usual source of care, delay in initiation of needed care, lack of health insurance, and underinsurance. While each of these measures provides important information about aspects of care access, unmet need encompasses the broadest range of causes and consequences of lack of access to care. In addition to unmet need, the Committee selected usual source of care and delay of needed care as related priority measures that provide detail about different foci of access to care. Usual source of care can be used to assess not only whether people receive care but also whether they receive it in a consistent and predictable way from a known source. Delay of needed care provides additional detail about the gray area between receiving and not receiving care, in which people may choose to delay or ration their care so as to reduce or avoid medical costs.

Disparities

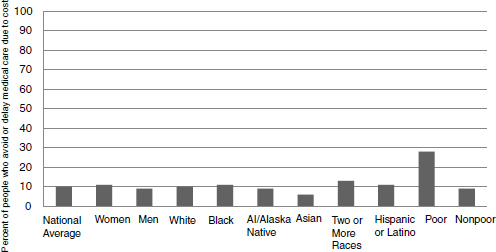

Unmet medical need, as defined by the percentage of people who delay or avoid needed care, exhibits disparities in terms of race and ethnicity, gender, education, residency status, and poverty status, as reported by the CDC (see Figure 4-13). In 2012 nationwide, an estimated 10 percent of people delayed seeking care because of cost. Unmet need was greater for women, at 11 percent, than for men, at 9 percent. In terms of race and ethnicity, 10 percent of white individuals delayed receiving care, compared with 11 percent of African Americans, 9 percent of American Indians/Alaska Natives, 6 percent of Asians, 13 percent of people who identified as two or more races, and 11 percent of individuals of Hispanic or Latino origin. Poverty also affects unmet medical need, which was experienced by 28 percent of poor individuals compared with 9 percent of those living between 250 and 400 percent of the federal poverty level (CDC, 2014c).

FIGURE 4-13 Percentage of people who delay medical care because of cost across demographic groups, 2012.

NOTE: AI = American Indian.

SOURCE: CDC, 2014c.

|

Patient Safety |

Importance

Avoiding harm is a primary obligation of the health care system, yet despite the steadily declining hospital mortality in the United States, one of every three hospitalized patients may be harmed during their stay, and one of five Medicare patients are rehospitalized within 30 days of admission (IOM, 2012a). These harms often are associated with certain risk factors, such as the use of indwelling medical devices, surgical procedures, injections, contaminations of the care setting, and misuse of antibiotics. Infections acquired in care settings are estimated to have an economic cost in the billions and to contribute to tens of thousands of lives lost each year (HHS, 2014b). Ensuring that patients are safe in all their interactions with the health care system requires a systematic, coordinated approach to the provision of care services, as well as a culture of care that makes safety a priority. Patient safety also is a critical challenge for providers outside of the hospital setting. For example, misuse or overuse of opioids, often the result of poor prescribing practices, can pose a significant risk to patient

safety, a challenge that includes such stakeholders as community providers, pharmacists, and local and state health agencies.

Avoiding adverse events is a complex challenge without a singular or simple solution, in part because measures of these events include counts of several different types of events. The CDC data also show that significant progress has been made since 2008 in reducing hospital-acquired infections. Making progress toward reducing the incidence of adverse events requires the coordinated action of a range of stakeholders not only within the provider community but also among patients and their caregivers.

Best Current Measure

The Committee identified hospital-acquired infection rate as the best current measure for patient safety. Data on avoidable adverse events are available from many sources, with some studies suggesting that certain adverse events are underreported (Seiden and Barach, 2006) and others suggesting that claims-based measures may have significant error. The CDC’s Healthcare-Associated Infection prevalence survey provides an annual national estimate for the incidence of some of the most common health care–associated infections in hospitals, and these data are considered both reliable and valid. An estimated 648,000 patients in acute care hospitals had at least one health care–associated infection, converted for presentation purposes to a rate of approximately 1,700 per 100,000 using data on annual admissions and discharges from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project’s (HCUP’s) National Inpatient Survey (Magill et al., 2014; Pfuntner et al., 2012). Health care–related adverse events also are monitored via the National Healthcare Safety Network and the Emerging Infections Program (CDC, 2014b). Some states require reporting of wrong-site surgeries, although there is no uniform nationwide reporting system for these incidents. Improvement and standardization are necessary for this measure.

A preferred measure would be a composite measure for patient safety that would reflect patient safety more broadly by integrating performance with the most important patient safety events, mapped against a fuller range of patient care settings. Such a composite might include wrong-site surgeries, hospital-acquired infections, medication reconciliation, and pressure ulcers. Although the formal specification of such a composite core measure will require careful research and testing to ensure that the measure reflects as clearly as possible the state of patient safety, the development of composites for this and other measures where current data are lacking is a priority for the implementation of core metrics.

Related Priority Measures

Alternative measures considered by the Committee include blood infection from intravenous (IV) lines, treatment-associated infections, patient safety measures, and never events such as wrong-site surgeries. In addition to the best current measure of care-associated infections, the Committee identified a second priority measure: unnecessary care. This measure is a step removed from but closely related to the concept of patient safety. As such, it may be useful for certain stakeholder groups with more specific interest in this area. Unnecessary care targets the overuse of certain services or care resources, driven in part by fee-for-service models of care that emphasize volume of services and reflected, for example, in the Choosing Wisely services unsupported by evidence (ABIM, 2014).1

Disparities

Variations are seen in the incidence and severity of patient safety events for some population subgroups, although additional research is needed to articulate the relationships between demographics and patient safety events. For example, an analysis of AHRQ data on patient safety incidents among veterans found that rates of postoperative hemorrhage or hematoma were highest among African Americans, while African Americans had the lowest rate for another patient safety incident, foreign body left during a procedure (Shimada et al., 2008). Another study found that Hispanic patients had better outcomes than white patients on 7 of 14 patient safety measures, although incidence rates were higher for Hispanic relative to white patients for two additional measures (Russo et al., 2006a).

Interpreting variations in the incidence of patient safety events can present an analytic challenge because of underlying variations in risk factors such as hospitalization rates and comorbidities. Additional measure development is needed to ensure that disparities in avoidable adverse events are monitored and addressed in health and health care improvement activities.

_______________

1 Choosing Wisely is an initiative of the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) aimed at identifying and eliminating unnecessary medical procedures and expenses.

|

Evidence-Based Care |

Importance

The quality, effectiveness, and consistency of care depend on the application of evidence to clinical circumstances. One of the central challenges for the American health system is ensuring that care delivered is based on the best available scientific evidence for appropriateness and effectiveness. While advances in medicine and health care have led to substantial gains in life expectancy and quality of life over time, many people still fail to receive recommended care or receive care that is not based on scientific evidence. One study found that people receive only about 55 percent of recommended care (McGlynn et al., 2003). As clinical research has progressed for various conditions, new ways of assessing predispositions to disease, as well as treating conditions, have been developed, and these are targets of the rapidly proliferating measurement requirements. Ironically, the plethora of measures has taken on a reductionist character, focusing attention narrowly rather than on activities with broad-based impacts on improving systems of care across the spectrum.

This proliferation of measures also deflects attention from things that ought not to be done. Choosing Wisely highlights the extent to which today’s health care practices are out of line with the evidence. Through the work of Choosing Wisely, more than 60 medical specialty societies have identified lists of “things physicians and patients should question,” highlighting common practices or procedures that are often overutilized or poorly deployed. For example, the American College of Physicians recommends against obtaining imaging studies for nonspecific low back pain, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends against the use of antibiotics for viral respiratory illnesses, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends against annual Pap tests for women aged 30 to 65 (ABIM, 2014). These lists, which are provided in formats for both physicians and patients, are intended to encourage conversations between doctors and patients about care that may not be supported by evidence and, in the process, to promote better alignment between clinical practice and evidence and assist patients in actively engaging in decision making about their care.

Best Current Measure

The Committee identified preventable hospitalization rate as the best current measure for evidence-based care. The Committee found that an