4

Policy-Related Imperatives for Change

If agricultural technologies and land use options exist that can make agricultural development in the humid tropics more sustainable, then why have they not been more widely adopted? Why has deforestation or forest conversion not been more effectively managed? There are no simple answers to these complex questions, as illustrated by the country profiles in Part Two of this volume. For countries in the humid tropics to make real progress toward sustainability, the broad range of social, economic, and political factors that affect land use patterns must be recognized and considered throughout the development process. Progress will depend not only on the availability of improved land use techniques, but on the creation of a more favorable environment for their further development, implementation, and dissemination. These changes must be achieved through the national and international institutions that determine the character of public policy.

The goal of the committee's policy-related recommendations is to meet human needs, at individual, national, and international levels, without further undermining the long-term integrity of tropical soils, waters, flora, and fauna— the foundations of sustainable development. The countries of the humid tropics will need to take the lead if these efforts are to succeed. The countries beyond the humid tropics will need to extend their support and be willing to make their own sacrifices. All countries will need to share the conviction that success is possible, and offer their commitment to its realization.

The strategy for change outlined here to promote sustainability in the humid tropics involves efforts to (1) manage forests and land resources more effectively and (2) encourage sustainable agriculture. Most reform efforts emphasize the removal of policies that have led to accelerated deforestation rates in recent years. Until now, however, these reforms have not focused on stabilizing and rehabilitating already deforested lands, nor have they served to guide small-scale farmers toward more sustainable agricultural production systems through forest conversion strategies.

Sustainable agriculture will not automatically slow forest conversion or deforestation in the humid tropics. However, the combination of forest management and the use of sustainable land use options will provide a framework within which each country can achieve an equilibrium appropriate to its development stage and natural resource use requirements. These systems can help to offset the impacts of heightened economic and demographic pressures on intact primary and secondary forests by improving the management of agricultural systems, diversifying crop production systems, stabilizing shifting agriculture on steep lands and in forest margins, and restoring degraded and abandoned lands.

At the same time, however, the ability to enhance the performance and profitability of croplands, pastures, mixed systems, or plantations may encourage further migration into and conversion of undisturbed forests. The combination of improved land productivity and further population growth could also result in higher land prices, causing small-scale farmers to migrate to cheaper lands at the forest frontier.

Pressures to extend sustainable agricultural systems to undisturbed forest will remain, especially where timber profits are high or population growth is rapid. In some areas, such as parts of Africa, Brazil, and Venezuela, additional conversion of forests to agricultural, or nonagricultural, uses may be necessary and appropriate based on national environmental and food needs. In all situations, however, technical innovations must be accompanied by policies that guide their applications and protect undisturbed forests.

Both the causes and consequences of nonsustainable land use in the humid tropics are global in nature. Action by, and coordination among, all countries will be required to effect change. Accordingly, the actions recommended here are wide ranging. Some apply primarily to the policies and activities of industrial nations, while others focus on developing countries within the humid tropics. All countries, however, stand to gain from multinational cooperation.

The changes discussed in this report focus primarily on low pro-

ductivity lands worked by small-scale farmers and on forested or recently deforested lands. An improved policy environment should, however, consider the role that highly productive agricultural lands and input-intensive agroecosystems play in protecting forests and stabilizing degraded lands. If the productivity of these areas can be increased in a sustainable manner, part of the pressure for expansion into marginal areas may be reduced.

MANAGING FOREST AND LAND RESOURCES

Sustainable agricultural practices cannot be expected to take hold in the humid tropics as long as development policies and economic forces continue to encourage more expedient uses of land resources. Governments, international development agencies, and other organizations have begun to address this fundamental problem, but the acceleration of deforestation rates through the 1980s indicates the need for a stronger commitment to reform. Recent analyses have described in detail national and international policies and their impact on tropical resources (for example, Barbier et al., 1991; Binswanger, 1989; Hurst, 1990; Leonard, 1987; Repetto and Gillis, 1988). This growing body of analysis points to the need for policymaking bodies at the local, national, and international levels to reexamine their roles and responsibilities in determining the future welfare of tropical land resources and the people who depend on them.

Reviews of Existing Policies

Policy reviews under way at local, national, and international levels must be broadened to consider the negative effects that policies have had on sustainable land use.

In response to escalating rates of deforestation and increased awareness of local, regional, and global effects, many international and bilateral development agencies have reassessed their forest policies. These include the Dutch Development Corporation, the Inter-American Development Bank, the Asian Development Bank, the Finnish International Development Agency, the World Bank, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, and the International Tropical Timber Organization (Spears, 1991). Most of the recent forest policy statements of these agencies focus on the forest resource itself, and analyze the changing market conditions, institutional and social forces, and policies that have encouraged forest conversion and deforestation. Few focus on the need for agricultural sustainability in responding to deforestation in the humid tropics.

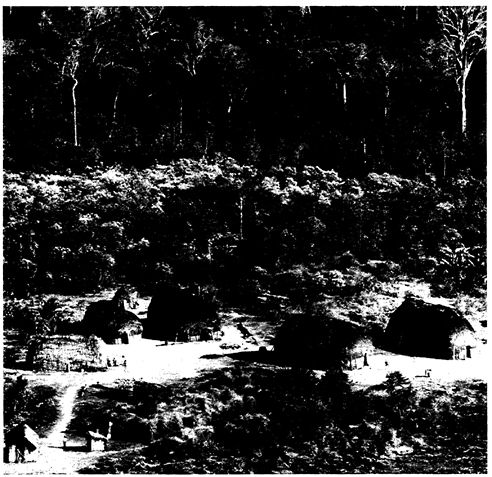

Land has been set aside for the Surui in Aripuana Park, Rondônia, Brazil. The Surui people resent the influx of settlers who, they say, destroy the forest and take the land. This small cluster of houses is nestled in a mixed garden setting surrounded by a partially converted forest. Credit: James P. Blair © 1983 National Geographic Society.

Government agencies within humid tropic countries have also adjusted policies in response to global environmental concerns and their own socioeconomic and environmental priorities. In recent years, for example, Brazil has removed the financial incentives that promoted conversion of forestland to large-scale cattle ranches and has put into place programs to encourage sustainable agricultural development (Serrão and Homma, Part Two, this volume). Brazil and Colombia have recently recognized the claims of indigenous people to large forest areas and have given them greater responsibility for

managing these areas. As new national policies are instituted, however, they can sometimes have unintended effects. In the wake of severe floods in 1988, for example, the government of Thailand instituted a ban on commercial logging. The subsequent rise in timber prices led to increased illegal cutting and failed to check the forces behind forest encroachment by shifting cultivators (Myers, 1989).

Efforts to review policies that contribute to deforestation are a prerequisite to sustainable land use in the humid tropics, and they merit expansion. At national and regional levels, policy reviews should respond to the specific biophysical, social, and economic circumstances that affect land use patterns within countries and regions. These reviews should also focus on the in-country effects of international trade, lending, and debt-reduction policies. At the international level, the review process will vary from institution to institution, depending on its size and objectives and the range of its activities.

Although the policy review process will necessarily vary, the following considerations are generally applicable.

-

Given the complexity of the socioeconomic and ecological aspects of land use in the humid tropics, reviews should be undertaken by multidisciplinary teams.

-

Economic policies that encourage large-scale logging and agricultural clearing should be identified and evaluated in terms of their externalized costs, social and ecological costs, and availability of transport infrastructure, such as roads and bridges. For example, the fees charged loggers for the right to cut standing timber seldom come close to the costs of replacing the volume removed with wood grown in plantations (World Bank, 1992). In general, these policies discourage long-term interest and investments in forest management (both in the public and private sectors), undervalue the full economic and environmental benefits of conserving primary forests, and hinder the adoption of sustainable land use alternatives.

-

New methods of assessing and assigning value to the forests should be sought. Reviews should assist in recognizing the full range of the forests' economic benefits, the key environmental services they provide, the potential for sustainable use of their resources, the opportunity costs involved in forest conversion, and the rights of future generations to forest services and products. When possible, values should be expressed in standard economic terms, such as financial costs and returns, with cost and benefit streams discounted to a common base. Those that cannot, such as aesthetic values and environmental services secured through conserving biological diversity, should nonetheless be explicitly noted in all economic analyses (Barbier et al., 1991; Norgaard, 1992; Randall, 1991).

-

Reviews should seek opportunities to integrate more fully the activities of the forest and agricultural sectors, and to incorporate an interdisciplinary perspective in development, research, and training programs.

-

Ways should be found to integrate infrastructure, land use, and development policies. Well-conceived infrastructure development policies can fail if sustainable land use technologies and systems are not in place to support them.

|

The Negative Impacts of Land Use Policies Despite increasing recognition of the importance of tropical forest resources, the exploitation of tropical forests to meet short- to medium-term development objectives still takes precedence over most long-term uses in many countries. Economic analyses and policies have failed to recognize the full market and nonmarket values of forest conservation and sustainable land uses. Thus many of the potential benefits of forest conservation are not realized. Similar economic factors have contributed to, and continue to support, deforestation in temperate zone countries, including the United States (Repetto and Gillis, 1988). Often national economic and land use policies contribute to this dilemma by directly or indirectly promoting the inefficient and nonsustainable conversion of forests to other uses. In many cases, the policies of international development agencies have encouraged these moves, especially as developing countries try to reduce their burden of outstanding debts. Areas with the highest rates of deforestation in recent decades include the Brazilian Amazon, the Philippines, Malaysia, and Côte d'Ivoire. A variety of economic incentives has encouraged exploitation of forest resources, including tax incentives and credits for land clearing, subsidized credit, timber pricing procedures, price interventions, land subsidies and rents, concessions, tenure, and property rights.

|

-

Finally, as institutions reexamine their priorities, they should recognize the need to better coordinate their efforts and institutional commitments. Lack of coordination—within national governments, among international organizations, and between international agencies and governments—often gives rise to conflicting resource policies. International development agencies, in particular, should seek opportunities to coordinate policies in support of conservation and sustainable development objectives in the humid tropics. The Tropi

|

-

cal Forestry Action Plan, developed by FAO, the United Nations Development Program, the World Bank, and the World Resources Institute, is an example of such a coordinated effort (Food and Agriculture Organization,1987).

Anticipated corrections as a result of these reviews include: reforms in tax, credit, and subsidy policies that remove incentives to

|

maximize timber production and that encourage more sustainable forest management techniques; international trade and financing reforms that can bring more realistic prices to tropical timber while reducing wasteful harvesting methods; clarification of property rights and support for local and indigenous land tenure; and changes in concession agreements to prompt greater investment in long-term forest management and reforestation efforts.

|

concessions for harvest or may empower its forest management agency to do so (Lynch, 1990; Rush, 1991). In many tropical countries, political corruption contributes to deforestation and other forms of natural resource degradation. Close ties between commercial timber interests and politicians have encouraged the exploitation of forest resources for political purposes (Rush, 1991). For example, the awarding of noncompetitive timber concessions through military and government contacts has significantly contributed to the rapid rates of deforestation in Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines (Garrity et al., Part Two, this volume; Repetto, 1988b). Under these circumstances, the tenure rights of indigenous people are often disregarded. Forestry regulations and guidelines affecting extraction techniques, rotation schedules, the environmental impacts of logging and processing operations, and reforestation requirements are ineffective due to lack of enforcement (Repetto, 1988b). Forest encroachment, poaching, timber smuggling, and other illegal logging practices become important problems (McNeely et al., 1990). In addition, corruption has allowed private timber interests to have undue influence on government subsidies, tax policies, the location of infrastructure development projects, and the distribution of land, aid, and credit. The impact of corruption can be seen in the case of the Philippines. Rush (1991) notes that access to timber concessions and other state-owned natural resources has played an important role in the political patronage system. Garrity et al. (Part Two, this volume) identify “large-scale corruption” as a distinguishing characteristic of the Philippine government during the late 1970s, when deforestation rates were particularly high. In many cases, timber operators in the Philippines have themselves held political office, making it impossible to enforce policies that would result in lower profit margins (Baodo, 1988). At the same time, deficiencies in community organization, training, and cooperative management at the local level have allowed forest regulations to be abused (Garrity et al., Part Two, this volume). Although the impact of political corruption on resource management is especially evident in South and Southeast Asia, where timber extraction has been especially lucrative, the same forces operate throughout the humid tropics as well as in temperate regions. |

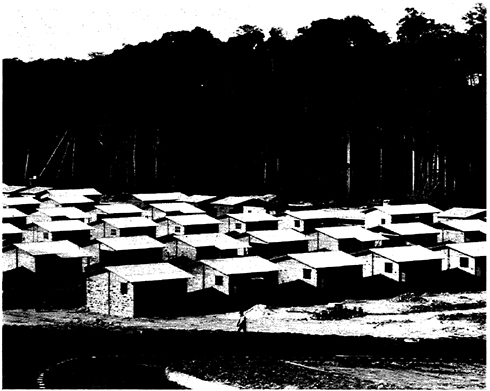

A housing development of about 15,000 units was carved out of the Brazilian rain forest. The tight clustering of houses reduces the use of land but dramatically decreases opportunities for low-income families to have mixed gardens and keep animals so critical to their well-being. Credit: James P. Blair © 1983 National Geographic Society.

Planning of Major Infrastructure Projects

Impact assessments of infrastructural development projects should be broadened to anticipate changes in land use systems and subsequent social effects.

Infrastructural development projects, usually undertaken with the backing of international development agencies, have caused widespread forest degradation in the humid tropics. The construction of mines, dams, railroads, highways, and logging roads directly and indirectly affects large areas of primary forest, leading to changes in land use. Larger areas are affected by soil, air, and water pollution, soil erosion and sedimentation, disruption of hydrological systems, forest fragmentation, and other associated consequences.

Until recently, these social and environmental costs were rarely

considered. The international development organizations that provide much of the support for these projects—such as the World Bank, other major development banks, and some bilateral donors—now require impact assessments. In many cases, however, these assessments have failed to prevent or mitigate adverse impacts. For example, high-sedimentation rates threaten the viability of dam projects throughout the humid tropics: Eljon in Honduras, Chixoy in Guatemala, Ambuklao in the Philippines, and Arenal in Costa Rica. Development proceeded without effective provisions for sustainable agriculture, watershed management, protection of adjacent forestland, forest restoration and rehabilitation, pollution control, and other mitigation measures. In the future, environmental provisions should seek to prevent land degradation by requiring that sustainable land use practices accompany infrastructure development projects from the outset.

The social impacts of these projects have also been inadequately addressed by governments and international agencies. Local communities and indigenous people are often displaced or disrupted despite their tenure or property rights. Moreover, infrastructural development often precedes or takes place simultaneously with resettlement and colonization projects, yet settlers are rarely provided with adequate tenure, tools, financing, or knowledge needed to use these lands sustainably. The result frequently is the perpetuation of the pattern of resource decline. Poor farmers gain access to primary forests, yet they continue to farm in a manner that depletes resources and keeps them impoverished.

These adverse social impacts need to be anticipated and, where necessary, mitigated. Development projects that entail relocation or resettlement should recognize the need for sustainable land use systems (and effective land use restrictions) in the surrounding cleared lands, forests, and watersheds. The tenure rights of indigenous people and colonists should be secured prior to major infrastructural development projects. Land titling is not always an issue in these cases, but where questions of ownership and usufruct rights exist they should be resolved before projects proceed. This approach was taken, for example, in the Pichis-Palcazu Project in Peru. Land titling and property boundary surveys were undertaken prior to road construction, allowing the native Amuesha-Campa communities as well as settlers to gain secure tenure before the influx of new migrants occurred.

National Resource Management Agencies

The mission of national resource management agencies as custodians of national forest and land resources should be redefined to focus more atten-

tion on achieving a balance among resource users. The strengthening of resource management agencies is a key area for cooperation among the governments of tropical countries and the international assistance agencies.

Throughout the humid tropics, national resource management institutions, particularly forest agencies, are often nonexistent or weak. Where they do exist, they receive limited political and financial support. While agricultural agencies generally receive the greater portion of financial support, they in turn allot little funding to forest-related activities or to research and development in sustainable agriculture (Okigbo, 1991; Repetto, 1988a; Villachica et al., 1990). Few national or state resource bureaucracies are capable of effective protection and stewardship of the resources under their jurisdiction, or of supporting basic or applied research in forest ecology, agroecology, farming systems, indigenous knowledge, or other areas relevant to sustainable land use. In some countries, effective agencies may need to be built from the bottom up through long-term investments. In others, where strong agency structures are already present, they may need to be better integrated.

The structure of resource management agencies is usually determined by discrete resource categories, such as agriculture, forestry, and environmental protection. As a result, the division of responsibilities —in legal jurisdiction and in scientific research, training, extension, and development programs—has made integrated management difficult. In these cases, it may be most effective to invest in training and continuing educational opportunities in the environmental sciences for agency personnel.

Biodiversity

Biodiversity should be conserved through both the establishment of forest reserves and the inclusion of broad genetic diversity as a basis for sustainable land use systems.

The development of sustainable agriculture and the protection of biodiversity are not two different undertakings, but allied aspects of conservation as a whole in the humid tropics. The diversity of soil organisms, plant and animal genetic material, pest and disease control agents, plant pollinators, symbionts, and seed dispersers underlies the functioning and productivity of tropical agroecosystems as well as managed forests (Edwards et al., 1991; Grove et al., 1990; Lal, 1991b; Pimentel, 1989). Improved management on more intensively used lands may ease the pressure to develop forested areas rich in biodiversity.

The establishment and effective management of forest reserves

should be seen as part of the development process. All lands can and should contribute to sustainable development. This alone justifies allocating resources for preserving lands and improving their stewardship. Moreover, some uses are permissible in reserves under certain circumstances and may warrant encouragement as part of a strategy of sustainable development. Examples would include scientific research and educational activities, low levels of extractive activities, recreation and ecotourism, and modest efforts to interpret the scenic and natural values embodied in these reserves. When properly planned and managed, these uses do not endanger the primary forest values that the reserves were created to protect.

Policies that simultaneously emphasize the goals of conserving biodiversity and implementing sustainable agricultural systems—especially policies aimed at improving the quality of life for small-scale farmers and local communities through conservation measures—need further development and additional support. From an agricultural and rural development perspective, the benefits of this integrated approach are substantial. Direct economic benefits can be realized through the identification of new products for local use and export. Investments in biodiversity research by industrialized nations can serve to transfer financial resources to countries in the humid tropics and strengthen local research institutions. The establishment, management, and maintenance of germplasm banks can protect local genetic resources, bring farmers and researchers closer together, and provide local employment. Biodiversity research (involving, for example, soil organisms and insect populations) can offer new insights and techniques for agroecosystems. Rural communities can provide services for visitors to national parks and biological reserves. The establishment of reserves and buffer zones can also protect the tenure rights, resources, traditional management methods, and knowledge of indigenous cultural groups.

Often the benefits of biodiversity conservation accrue outside the local community. For example, germplasm from the humid tropics has improved crop productivity in the temperate zone. These contributions must be recognized and efforts made to obtain benefits for the local population. Incentives to identify important natural areas, and to protect and manage them, should be made available to farmers and communities. Creative partnerships between local people and research organizations, management agencies, funding agencies, nongovernmental organizations, and private enterprises can help to ensure that the benefits and costs of conservation are fairly distributed (Altieri, 1989; Brush, 1989).

Global Equity Considerations

The adoption of sustainable agriculture and land use practices in the humid tropics should be encouraged through the equitable distribution of costs on a global scale.

Industrialized countries have a responsibility to assume a proportionate share of these costs, to compensate the countries of the humid tropics for foregoing the short-term economic benefits of resource depletion, and to provide incentives for conservation measures that provide global benefits (Sachs, 1992; Swanson, 1992). Strategies for cost-sharing have already been devised to promote reductions in global atmospheric carbon emissions (through, for, example, carbon taxes and permit trading). At the same time, economic analyses are beginning to explore the means by which environmental costs and benefits may be reflected more accurately in markets and incorporated into international development, trade, and lending policies (see, for example, Costanza and Perrings, 1990; Norgaard, 1992). These innovative cost-sharing and valuation methodologies are becoming increasingly important in achieving a broad range of environmental and development goals, and should be supplemented with other foreign assistance mechanisms that promote equity at the global level.

The World Bank (1991) emphasizes three broad areas of assistance through which the international community can facilitate the transfer of resources and the conservation of tropical resources: technical assistance, research, and institution building; financing; and international trade reforms. Within these categories, a number of specific measures can be adopted. Direct transfers of funds allow the countries of the tropics to decide how to allocate these funds. Other forms of transferral may better meet other, more specific needs. For example, debt-for-nature swaps, which have been arranged with Brazil and several other countries, may be most important in countries with high foreign debt burdens. Investments in institutions or carefully planned infrastructure projects may be more beneficial in countries where these institutions and projects are weak. Improved access to markets and better terms of trade can serve to promote new products and to achieve more equitable trading patterns. Innovative partnerships and exchanges—scholarships and stipends for students in resource management, collaborative research enterprises, private investments in new products from the tropics, and funding for programs in public health and community development —link conservation and development activities. The objective in all of these examples is the same: to use the financial and institutional resources of developed countries in encouraging the conservation of natural resources and the development of human resources in developing countries.

SUPPORTING SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURE

Changing policies that contribute to deforestation and natural resource degradation in the humid tropics will not by itself encourage the adoption of sustainable agricultural systems. The fact that land use alternatives exist does not ensure they will be widely adopted by farmers. International and national institutions need to support these alternatives at all phases of development, dissemination, and implementation. Without support, sustainable agricultural practices are likely to be adopted only slowly and erratically.

The overarching need throughout the world's humid tropics is to implement land use systems that simultaneously address social and economic pressures and environmental concerns. In areas where short-fallow shifting cultivation is the leading proximate cause of defores-

Cacao is an important cash crop in many developing countries. Pictured is a plant growing in Africa. Credit: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

tation and land degradation, the primary goal should be to encourage shifting cultivators to adopt alternatives to low-yielding, slash-and-burn agriculture. In areas where other causal factors are important, actions should reflect the potential of sustainable agricultural systems to reduce these pressures and mitigate their effects. In all areas, much greater emphasis needs to be given to the rehabilitation, restoration, and reforestation of degraded and abandoned lands.

Efforts to support sustainable agriculture can be grouped into three categories:

-

Providing an enabling environment;

-

Providing incentives and opportunities; and

-

Strengthening research, development, and dissemination.

Within these categories, a wide range of reforms and initiatives need to take place at the local, national, and international levels.

Providing an Enabling Environment

National governments in the humid tropics should promote policies that provide an enabling environment for developing land use systems that simultaneously address social and economic pressures and environmental concerns.

Many small-scale farmers and forest dwellers in the humid tropics are unable to adopt sustainable practices due to local socioeconomic and infrastructural constraints. The policy initiatives described here are intended to provide guidance for removing basic obstacles and providing opportunities for sustainable practices to take hold. Essential components of an enabling environment include assurance of resource access through land titling or other tenure-related instruments, access to credit, investment in infrastructure, local community empowerment in the decision-making process, and social stability and security.

LAND TITLING AND OTHER LAND TENURE REFORMS

More than any other factor, the status of land tenure will determine the destiny of land and forest resources in the humid tropics. This conclusion holds true for all classes of local land users—native peoples and forest dwellers as well as more recent settlers and small-scale farmers.

Indigenous forest dwellers retain their traditional territories in many parts of the humid tropics, but their territorial rights are seldom secure. In many cases, the government agencies that hold juris-

diction over resources have not even acknowledged the presence (much less the claims) of native peoples. Because many indigenous territories overlap areas of commercial concessions, these groups often face arbitrary displacement or destruction of their homelands (Lynch, 1991). Their tenure systems, many of which are based on common property systems of management, are often incompatible with national laws and difficult to delineate and protect. As a first step in the process of bringing sustainable and equitable land use to the humid tropics, the legitimacy of these territorial rights and tribal domains, and their value in forest conservation and development programs, should be recognized.

For hundreds of millions of small-scale farmers and other resource users in the humid tropics whose livelihoods depend on access to land and forest resources, tenure issues are fundamental to their choice of land use practices and to their future welfare. Lacking secure tenure, farmers and other small-scale resource users have little incentive to conserve, manage, improve, or invest in land resources. Deprived of the benefits of local resources, they must often overexploit those to which they do have access. Lack of tenure also contributes to mutual animosity among small-scale users, large landowners, government officials, and resource bureaucracies, and hence to a diminished public capacity to respond to the need for resource conservation.

The mechanisms by which insecure tenure results in resource degradation vary widely throughout the tropics. In some areas, inappropriate tenure arrangements, such as inequitable share-cropping requirements or lack of secure ownership, force farmers into short-term behavior —encroachment onto marginal lands, cultivation of steep slopes, and intensified cycles of shifting cultivation. Often the process is more passive; lacking secure tenure, farmers are discouraged from investing in terracing, agroforestry systems, timber plantations, tree crops, and other long-term land improvements. Moreover, they are often unable to make investments because they require credit to do so, and credit, if available, is extended only to those who have tenure and can pledge their land as security. Breaking this cycle is particularly important in countering the tendency of shifting cultivators to enter new areas and in removing the obstacles to the reclamation of abandoned lands. Ownership of land is often transitory in areas where shifting cultivation is widely practiced. Few farmers in these areas are able or willing to invest in alternatives to slash and burn, which typically involve planting trees in agroforestry and other mixed systems, if they do not have secure tenure (Sanchez, 1991).

In all these cases, tenure arrangements that provide long-term

access to land resources are prerequisites to efficient land-use decision making and to the implementation of sustainable land-use systems. This need is beginning to be recognized in national mandates and allocation legislation in many tropical countries—Brazil, Colombia, Indonesia, Peru, and the Philippines, among others—but these moves are often difficult to enforce. Economic and political elites who benefit from existing tenure arrangements are resistant to change. In addition, many national forestry and other resource agencies are actively opposed to these policy changes, fearing that recognition of tenure will eliminate the role of foresters and other government agency officials. This fear, for example, has impeded progress in the Philippine government's efforts to delineate indigenous territorial boundaries (Garrity et al., Part Two, this volume; Lynch, 1991).

The importance of tenure provisions is also beginning to be recognized and incorporated in the programs of bilateral and international development agencies, human rights and conservation organizations, and other nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) (Plant, 1991; World Resources Institute, 1990b). Perhaps most significant, local and indigenous people themselves are more aware of their stake in tenure disputes and of their protection under international law (Lynch, 1991). In addition to immediate support for efforts to improve the status of tenure for small-scale farmers and indigenous people, development agencies should support much-needed research in the social sciences on a wide variety of tenure issues: accurate, country-specific demographic surveys of the number and distribution of people in forests and forest margins; forms of tenure and their connection to land use, agricultural productivity, and conservation practices; traditional means of resolving tenure and resource disputes within and between local communities; the role of women in various tenure systems; the changes in tenure that have accompanied modern settlement and forest conversion; and conflicts between traditional and modern tenure systems.

Even as research continues to illuminate the important connections between tenure reform and sustainable land use, national governments in the humid tropics should endeavor to resolve tenure disputes and to anticipate and prevent future conflicts. Territorial boundaries should be delineated and land title granted prior to infrastructural development projects and resettlement programs. This is especially important in areas where migrants are encroaching on areas traditionally used for extraction (as, for example, in the rubber tapping regions of Acre in Brazil) or on tribal lands (as in the Yanomani lands of Brazil and Venezuela, where in the last decade gold mining has resulted in a rush of new settlers). Such conflicts are never easily

resolved once they develop, and the best strategy is to build preventive measures into all development planning.

ACCESS TO CREDIT FOR SMALL-SCALE FARMERS

Lack of access to credit is a major constraint that shifting cultivators and other small-scale farmers face in improving their resource use. While some sustainable land use practices can improve productivity even in the absence of credit, most will require long-term investments, since the costs of implementation will not be recovered in the short term. In areas where the chemical and nutrient limitations of soils were traditionally overcome through slash-and-burn cycles, credit for initial soil preparations can be critical in the period of transition to sustainable systems. Credit is essential in areas where soil amendments, seeds, tree stock, tools, and other purchased inputs are needed to initiate land rehabilitation and the conversion of destructive shifting agriculture or cattle ranching to more stable systems. The provision of both credit and secure tenure is especially important in rehabilitating badly degraded lands, where the rebuilding of “biological capital ” requires substantial investments of time and money.

Credit mechanisms and structures should vary to suit local social and land use conditions, and innovative arrangements should be encouraged. The Grameen Bank in Bangladesh, a community-based cooperative development bank that makes small grants and loans, is one example (World Resources Institute, 1990b). Innovation in credit programs, however, must entail careful planning to ensure they promote flexibility in land use and do not lock farmers and other landowners into nonsustainable practices. The objective is to give small-scale farmers the means to adjust their operations and adopt new practices that encourage the local rehabilitation, sustainable use, and conservation of resources.

INVESTMENT IN INFRASTRUCTURE

National and international infrastructure investment policies have often encouraged access to and through primary forests. In the future, infrastructural development's primary aim should not be to advance deforestation, but rather to support more appropriate land uses on already cleared lands.

Strengthening the connections between the small farm and the market can be an efficient and cost-effective means of stimulating the diversified activities on which sustainable land use largely depends (Brannon and Baklanoff, 1987; Gómez-Pompa et al., Part Two, this

volume). This implies the provision of reliable roads, bridges, and railroads, suitable processing equipment, adequate storage facilities, and improved marketing mechanisms (particularly for new products). Improved transportation networks are needed not only to allow farmers to market their products, but to enhance their access to necessary inputs, including information through extension services and other means. Storage facilities are needed to protect tropical products, many of which are highly perishable, from spoilage and postharvest pest problems. Processing equipment is needed to convert products into more readily marketable forms (often with value-added benefits to local economies), and to develop new products for local use as well as national and even international export. Improved marketing mechanisms and facilities can create additional opportunities for traditional and newly developed products.

LOCAL DECISION MAKING

If sustainable land use practices are to be successfully introduced, they must be responsive to the concerns and needs of small farms and rural communities and adaptable to local social, economic, and political conditions (Chambers et al., 1989; Edwards, 1989). The annals of development agencies contain many cases of well-intended projects that have failed due to inadequate farmer and community participation in project development, planning, and management. Farmers who do not have a stake or perceived self-interest in developing a locally suitable agroforestry project or mixed cropping system will not be committed to its success. Where local people participate in the planning process, and receive immediate benefits, the results can be striking (Gómez-Pompa et al., Part Two, this volume).

Local responsiveness calls for modifications in conventional approaches to development planning. Especially under the highly variable conditions of communities in the humid tropics, top-down strategies that emphasize only the transfer of technologies from centralized research stations to farmers are prone to assume or overlook key biophysical, social, political, or cultural factors that determine the local acceptance of land use practices. National and international development agencies, policymakers, and institutions need to involve local communities from the inception of planning on all projects, beginning with a realistic appraisal of the problems, needs, desires, and opportunities that farmers and communities face (Chambers et al., 1989; Gómez-Pompa and Bainbridge, 1991). These assessments need to take into account the status of local natural resources and community needs, using this information to plan and implement better coor-

An agroforestry program, sponsored by the Food and Agriculture Organization in a deteriorated region of Madagascar, incorporates the cultivation of trees with other agricultural production for integrated rural development. Pictured is an improved breed of chicken. Credit: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

dinated development programs. In many parts of the humid tropics, for example, education and public health services can be better integrated with sustainable land use goals. The development agencies can play a critical role by providing technical assistance in community planning.

The social forestry programs that have been implemented in several Southeast Asian countries provide important working models for the increased participation of local farmers and communities in the humid tropics. Social forestry programs work with local communities to provide training and incentives for reforestation, forest protection, the local use of forest products, and the implementation of plantation and agroforestry projects on private and communal lands. By 1987, some 10,000 households, representing 10,000 ha of forestland, had become involved in Indonesia's Social Forestry Program, with the ultimate goal being the rehabilitation of 270,000 ha of degraded forestland (Kartasubrata, Part Two, this volume). In the Philippines, the Community Forestry Program has met with early success in its efforts to give upland farmers and forest dwellers greater ac-

cess to, and responsibility for, local forest resources (Garrity et al., Part Two, this volume).

Programs such as these hold great promise, but they are also confronted with many difficulties: the reluctance of governments to undertake needed reforms in land tenure; insufficient funds for needed subsidies and appropriate infrastructure; poor coordination among resource agencies; corruption and abuse in program administration; a lack of personnel with the necessary mix of skills in forestry as well as training in management and community development; a lack of tried and tested, locally adaptable agroforestry technologies; and a shortage of technicians willing to work with farmers (Garrity et al., Part Two, this volume). These deficiencies should not diminish the importance of social forestry and other experimental efforts to communicate the needs of small-scale farmers and foster the participation of local communities. Rather, international agencies and national governments should carefully review the record of these initial successes and failures, and work together to build programs that anticipate problems through the closer involvement of the users—the small-scale farmers and forest dwellers.

Providing Incentives and Opportunities

National governments in the humid tropics and international aid agencies should develop and provide incentives to encourage long-term investment in increasing the production potential of degraded lands, for settling and restoring abandoned lands, and for creating market opportunities for the variety of products available through sustainable land use.

In many cases, the steps already outlined will provide the conditions under which more sustainable agriculture can take hold and evolve. In these instances, the economic and environmental benefits of alternative practices and products are obvious and accrue quickly enough to induce individual farmers and local communities to make the necessary investments of time, labor, and money. In other cases, however, additional steps may be needed to stimulate investment and action.

INCENTIVES TO ENCOURAGE INVESTMENTS IN LAND IMPROVEMENT

The most promising methods of sustainable land management are often financially marginal in the short term. Some require terracing and other land improvement investments. Others may include the use of perennial crops that entail long establishment times and

high start-up costs. These costs may be especially prohibitive where the lands themselves are difficult to work (for example, uplands, steep slopes, poorer soils, soils that have been badly degraded in the process of clearing, and areas overtaken by tenacious weed or grass species). While various sustainable systems and agricultural practices hold great promise in stabilizing and improving these lands, the immediate financial returns may be inadequate to attract farmers and investments. Reform will be particularly difficult when decreases, rather than increases, in the productivity of the land are required. In such cases, alternative employment opportunities are a most probable solution, but it may be necessary to provide direct subsidies to compensate landholders while they allow their properties to stabilize.

Policy devices that have encouraged deforestation in the past—tax abatement, credits, pricing policies, concessions, and subsidies —can be revised to induce small-scale farmers and other landholders to adopt sustainable agricultural practices. Optimally, national development agencies and international aid agencies would work together toward this goal. With a consortia of researchers, NGOs, and other institutional interests, they would identify the lands of greatest need, gauge local community conditions, coordinate appropriate land use and conservation measures, and help provide the financial backing for investment programs.

To attain the most efficient use of limited funds, it will be necessary to determine where natural regeneration is proceeding most acceptably and investments can be delayed or used most sparingly, and where human needs are more pressing and regenerative processes require “boosting.” As regeneration and economic development proceeds, the mix of land use inputs is likely to change and so too will the mix of appropriate incentives. Thus, for example, labor-intensive agroforestry systems that might be highly suitable in low-wage countries may be less financially viable in high-wage countries. Some degree of anticipation of the consequences of changing economic and agroecological conditions is prudent. The necessary initial steps, however, remain clear: provide local farmers and communities in the humid tropics with incentives to improve their current land use practices and restore degraded lands.

INCENTIVES TO ENCOURAGE REHABILITATION OF ABANDONED LANDS

The incentives and investments just described will mainly affect lands that are already inhabited but in a degraded state. Special measures must also be taken to rehabilitate completely abandoned

lands. Throughout the humid tropics, land abandonment has often followed deforestation. This pertains in particular to those lands that have been heavily exploited for timber and cattle ranching in recent decades. Over vast areas, these lands have simply been logged and then abandoned. In others they have been purposely cleared for (or converted after logging to) agricultural uses that have proved, for one reason or another, nonsustainable. The growth of secondary forests will take decades.

In either case, there are definite strategic and logistical advantages to focusing on abandoned lands. If small-scale farmers can be helped to return abandoned lands to productivity, these lands can absorb populations, provide local employment opportunities, ease the pressure to extend deforestation, and stabilize soils and watersheds. Moreover, most abandoned lands retain at least rudimentary transportation and market infrastructures that can be improved with proper investments. Securing tenure on abandoned lands is a critical step in their rehabilitation, but special concessions may be required to attract farmers, especially landless shifting cultivators, to these areas.

Abandoned lands are heterogenous. The methods and goals of restoration vary, and so must incentive strategies. Lands that have been overtaken, for example, by Imperata cylindrica and other invader species may require incentives to induce tree planting and fire protection efforts as small landowners convert to agroforestry and perennial crop systems. Lands where the nutrients have been depleted and ash inputs are low require fertilizers. Tillage operations are needed on seriously compacted lands. Abandoned or degraded pastures in the Brazilian Amazon and elsewhere will require incentives for intensified management through improved forages, fertilization, crop introduction, and weed control. In areas where fuelwood needs are acute, reforestation with fast-growing trees may be the highest priority. Where commercial logging has opened steep slopes, the immediate need is for vegetative cover; where some cover has been restored, additional terracing or contouring may be needed.

Needs will not only vary from region to region, but also within regions. Depending on local tenure arrangements, it may be necessary to target subsidies, tax concessions, and other incentives toward villages and communities instead of (or in addition to) individual landowners. This is especially important in situations where the stabilization of entire watersheds is critical, and points to the importance of landscape-level planning in treating abandoned lands.

Additional incentives, not specifically aimed at site rehabilitation, are nonetheless necessary for restoring abandoned lands. Local

and regional market incentives may be needed to stimulate demand for products raised on these lands. Subsidies are usually required to build tree nurseries and processing facilities. Government agencies often retain exclusive responsibility for tree nursery management, thus discouraging private investment. However, privatization can be a desirable means of stimulating investment. Incentives for investment in collaborative research, demonstration areas, and education and extension projects may also be needed to build the local knowledge base.

MARKETS FOR AGRICULTURAL AND FOREST PRODUCTS

In developing market opportunities, it may be difficult for new products to compete with established humid tropical crops such as rubber, cacao, and oil palm. Opportunities may exist, however, to produce a wide variety of lesser-known crops and other products if market outlets for them can be developed. These can be incorporated into many land use systems as alternative crops in more intensive cropping systems, as trees in agroforestry systems, as restoration agents (particularly through the use of acid-tolerant cultivars), and as harvested products from extractive reserves.

Examples of potentially important products include the peach palm (Bactris gasipaes); achiote (Bixa orellana), a colorant; guaraná (Paullinia cupana), a flavoring for soft drinks; Brazil nut (Bertholletia excelsa); and fruits used in juice concentrates and other food products. The growing industrial and service economies of Asia, for example, are providing enormous market potential for forest products. This is only a partial list of food products from the Amazon Basin. Many other potential crops exist elsewhere in the humid tropics, including a wide variety of fruits and spices in humid tropic Asia. Medicines, resins, oils, latex, gums, fibers, and other materials have the potential to reach wider markets. Efforts to establish a specific international market niche for new products can take advantage of the developed world's changing values as reflected by its rising interest in environmental issues. Reliance will likely need to be placed on public institutions for market intelligence, establishment of grades and standards, and possibly the creation of a means of addressing the risks, such as insurance, protection from pests and pathogens, and genetic improvement. Market development is best undertaken by the private sector.

Development programs should be prepared to foster awareness and cooperation among private and public sectors concerned with sustainable land use (Kartasubrata, Part Two, this volume). For-profit firms can serve an important function by stimulating new investment

and enterprises at the local level, and their responsible participation should be encouraged through an appropriate mix of rewards, incentives, and disincentives. As interest in the conservation of tropical forests has grown, so have examples of creative, collaborative investment. Recently, for example, Merck and Company, a U.S.-based pharmaceutical firm, entered into an agreement with the government of Costa Rica to “prospect” native flora and fauna for natural chemical compounds with commercial potential. By providing $1 million over a 2-year period, Merck has acquired exclusive rights to screen materials collected by Costa Rica's Instituto Nacional de Biodiversidad (National Biodiversity Institute, INBio). These funds and others from U.S. and European universities, foundations, and governments will establish INBio' s chemical prospecting activities. This effort is designed to make the forests pay for themselves and to acquire the technology needed to screen natural compounds. Other arrangements to conserve the country 's biodiversity include the exchange of patent rights for royalties.

It is also important that the research underlying market development be undertaken as an interdisciplinary endeavor, and that it directly involve farmers and forest dwellers. Economists, social scientists, and natural scientists should collaborate with each other and with farmers to determine the best means of introducing new products and to assess their long-term impacts on farm performance, farmer income, community development, genetic diversity, and ecosystem composition and function.

STRENGTHENING RESEARCH, DEVELOPMENT, AND DISSEMINATION

New partnerships must be formed among farmers, the private sector, nongovernmental organizations, and public institutions to address the broad needs for research and development and the needs for knowledge transfer of the more complex, integrated land use systems.

The successful adoption of sustainable agricultural systems and practices requires a strong network for research, development, and dissemination of information.

New Methodologies for Research and Development A comprehensive, interdisciplinary approach to research, education, and training is fundamental to developing and managing the complex, sustainable agroecosystems of the humid tropics. The land at greatest risk of degradation is of modest production potential due to slope, limited availability of water, and soils that are low in fertility and highly

erosive. These lands require technologies quite different from high-productivity lands, which have received the bulk of agricultural development attention.

The international community has given substantial support for research to increase the productivity of major crops such as rice and maize, and for research on tropical soils, livestock, chemical methods of pest control, human nutrition, and other aspects of agriculture in developing countries (McCants, 1991). Much less research has been directed toward smallholder agroforestry systems, tree crops, improved fallow and pasture management, low input cropping, corridor systems, biocontrol and other methods of integrated pest management, and other agricultural systems and technologies appropriate to higher risk land types. Research in these areas has begun to receive greater attention. The activities, for example, of the International Center for Research in Agroforestry in Kenya and of the Centro Agronómico Tropical de Investigación y Enseñanza (Tropical Agriculture Research and Training Center) in Costa Rica have recently been expanded. Additional support for similar initiatives is needed.

It is important that the research knowledge base be expanded geographically and adapted to particular climatic, biotic, soil, and socioeconomic situations. Specific research needs for different land use options vary. All, however, require validation research and effective means of gathering and disseminating information. More on-farm testing and research should involve the rehabilitation, sustainable use, and management of recently cleared, degraded, and abandoned lands. This work should focus on the potential of these lands to support intensive agriculture as well as less intensive agroforestry and forest management systems. Sustainable agricultural technologies exist for these lands, but they require much more refinement and usually yield low rates of return to capital, management, and labor. No-tillage agriculture, for example, could be used on steep slopes throughout the tropics, but economical and environmentally sound methods of weed control are needed.

As new methodologies for research are developed, they can build on the efforts of existing methods. Studies of productivity constraints will continue to be necessary, but effective solutions to the agricultural problems of farmers on marginal lands are unlikely to be found solely through experiment station and laboratory research. As basic agronomic research continues, there is increasing need for studies that emphasize the experience and experimentation of farmers. On-farm studies themselves often suggest questions for further laboratory-based research (Chambers et al., 1989).

Participation of Nongovernmental Organizations The diversity and complexity of agroecological, political, social, and economic conditions throughout the humid tropics require a degree of sensitivity and microadaptation that large, centralized development agencies, especially those operating at the international level, do not and cannot efficiently provide. Only locally based organizations can handle the complexity that arises out of local conditions, while serving as conduits for the flow of information to, from, and among local farmers and communities.

The burgeoning of nonprofit private voluntary organizations (PVOs) and NGOs in the developing world is a response to this need. While many of these organizations focus specifically on conservation and agricultural development, many others with an interest and a stake in land use issues lack the experience, resources, and personnel to follow up on their concerns. National and international development agencies need to foster the productive involvement of local NGOs as intermediaries between themselves, national government agencies, universities, and local communities in support of the methods and goals of sustainable land use.

In particular, NGOs can assume a prominent role in training and education at the community level, in partnership with (or in the absence of) official extension services. NGOs can also serve as vital links in improved communication networks, connecting local farmers with researchers, agency administrators, aid officials, and other development workers. Perhaps most important, local NGOs are likely to be more effective than external organizations in shaping environmentally and socially acceptable land use policies based on local needs and priorities.

The organizations that comprise the NGO and PVO community are highly diverse (National Resource Council, 1991a). Some are international, others indigenous; some are community based, others are national associations; some consist of poor farmers, while others are well-funded urban institutions. Relatively few, however, have extensive research and extension capabilities in sustainable agriculture or resource management. For this reason, those groups that are in place and prepared to assume greater responsibilities involving land use issues should receive increased support for technical training.

Support for training may take the form of direct funding or innovative collaborative linkages with other organizations having needed expertise. NGO linkages with established agricultural development institutions, such as the international agricultural research centers and national agricultural research systems, have been limited by mutual distrust or by a lack of collaborative mechanisms. As institu-

tional barriers are overcome, and new mechanisms developed, development projects increasingly bring together a wide array of public and private organizations.

In 1984, for example, the Cooperative for American Relief Everywhere, the New York Zoological Society, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), and the Ugandan Forestry Department initiated the Village Forest Project in southwestern Uganda. The goal of the Village Forest Project is to improve living conditions for local farmers through the introduction of agroforestry techniques while simultaneously reducing pressures on the Kibale Forest Reserve, a protected area of moist lowland forest (Cooperative for American Relief Everywhere, 1986; Struhsacker, 1987). The International Center for Research in Agroforestry provides on-site technical assistance. The Sustainable Agriculture and Natural Resource Management program of USAID is attempting to bring the same collaborative spirit to a full range of sustainable resource management issues in developing countries (National Research Council, 1991a).

Dissemination of Information Through Extension Services The implementation of sustainable agriculture systems and practices in the humid tropics will require the active involvement of extension services. Decentralization, local adaptation, and innovation are key to the successful adoption and refinement of these systems, and extension services can be adapted to meet these needs. Working together with NGOs and others in the private sector, extension personnel can link farmers, researchers, resource agencies, community officials, and development officials. Through them, agencies should promote relevant research findings, develop demonstration projects and networks, and disseminate the information, management practices, plant materials, and tools necessary for the wider application of sustainable agricultural systems. Information, however, must flow both ways: extension workers should assist researchers in identifying the socioeconomic, environmental, and agronomic constraints that small farms and rural communities face.

Sustainability begins with an approach that is attuned to these environmental, social, and cultural realities, to local belief systems, and to traditional methods and knowledge. Accordingly, future extension services need to adopt an interdisciplinary approach. Extension personnel may require exposure to and training in aspects of land use and the environmental sciences that they have not previously received, including forestry and agroforestry, land use planning and zoning, and the conservation of biological diversity. In addition, the social aspects of rural development must become a more

prominent part of all extension services. Rural women, in particular, will need to be involved more actively in extension activities.

Education and training programs at all levels can benefit from adopting similar interdisciplinary approaches. Educational materials incorporating research findings need to be developed for use in schools and communities at all levels. Where training for work with natural resources is unavailable in-country, support should be provided for scientists and resource managers to receive graduate and postgraduate training in countries where appropriate programs are available, with the requirement that scientists return to their countries of origin to work.

OTHER POLICY AREAS AFFECTING LAND USE

This report is principally concerned with the implementation of improved agricultural techniques and the rehabilitation of degraded lands. However, other areas of public policy significantly affect sustainability in the humid tropics. These include political and social stability, population growth, greenhouse warming, and alternative energy sources.

Political and Social Stability

In the humid tropics, as elsewhere, long-term patterns of land use and the status of land resources are determined, in part, by the degree of stability within the society and its political institutions. The problems of resource management, and of deforestation in particular, cannot be separated from the issues of urban poverty, social justice, economic inequity, ineffective administration, deteriorating urban infrastructure, political corruption, agrarian reform, human rights abuses, and other pressing social concerns. Environmental degradation often reflects the desperate competition for access to resources under unstable social conditions, and unless these conditions are addressed, it will be impossible to make progress toward sustainable development (Latin American and Caribbean Commission on Development and Environment, 1990; Rush, 1991).

Under unstable conditions, both urban and rural populations are less likely to be concerned with long-term environmental health and more likely to engage in activities that yield short-term benefits. Declining environmental conditions, in turn, increase the degree of social and political instability. In the extreme case of warfare, traditional patterns of resource use can be grossly disrupted, and entire agricultural, wetland, and forest areas degraded through clearing,

defoliation, burning, draining, and bombing. Large expanses of land throughout Southeast Asia and Central America have experienced this fate over the past three decades (Office of Technology Assessment, 1984). The self-reinforcing cycle of social instability and environmental degradation fundamentally undermines the conditions necessary to sustainable use of resources: the mixture of technological innovation, education and access to information, long-term investment, policy reform, political empowerment at the local level, and economic and demographic stability.

Population Growth

There is little hope of accomplishing sustainable land use unless population growth is brought under control. The world's population is expected to increase by a billion people each decade well into the twenty-first century, with the developing nations of the tropics accounting for most of this growth. Because underdevelopment and poverty are directly related to higher fertility rates, any strategy for resource conservation in the humid tropics must entail strong policies to reduce poverty, an effort that could take many years.

Short-term problems of population distribution are commonly solved by resettlement. However, this approach to reducing local population pressures typically results in a host of new social and environmental problems. In many countries of the humid tropics, national resettlement policies and programs have resulted in large numbers of settlers moving into primary forests. This has occurred, for example, in the Philippines in the 1950s and 1960s, and more recently under the large-scale resettlement programs in Indonesia and Brazil (see Part Two, this volume). In other cases, such as Mexico, areas slated for colonization programs have first been prepared for settlement by the commercial extraction of valuable timber (Gómez-Pompa et al., Part Two, this volume). Whenever possible, resettlement policies should provide opportunities for transmigrants to develop abandoned lands and other less sensitive ecosystems.

Greenhouse Gas Emissions

Over the next several decades, sustainable agriculture and land use systems in the humid tropics can play an important role in efforts to stabilize and possibly reduce greenhouse gas concentrations. Evolving policies need to recognize, encourage, and reward actions that allow this potential to be realized. International climate change negotiations and agreements should proceed with greater emphasis on

the benefits of sustainable land uses in the humid tropics. The overriding goal should be to provide incentives and opportunities for improved land use at the local level.

Current international policy discussions on carbon dioxide emissions must consider more systematically the ability of sustainable land use systems in the humid tropics to reduce atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations by slowing deforestation, withdrawing carbon and storing it in plant biomass and soil, and providing alternative sources of energy. Changes in land use offer a practical means of removing large quantities of a greenhouse gas from the atmosphere through human intervention (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 1990b). Yet, even the best economic models and analyses involving the abatement of carbon dioxide concentrations focus primarily on the costs of reducing industrial emissions. Most do not factor in the positive contributions that sustainable land uses in the humid tropics offer (Darmstadter, 1991).

However, this potential should not be overstated. Improved land use in the humid tropics alone cannot offset the impact of industrial emissions of carbon dioxide. The capacity to sequester carbon through land use changes should not imply an abdication of the responsibility of developed countries to bring emissions under control. Support for land use changes that have local benefits can also provide global benefits, but not in the absence of policy changes that affect industrial emissions.

At the international level, the question of equity will continue to be a critical factor in the success of efforts to mitigate global warming. Although many in the international community share a deep sense of purpose and responsibility within the arena of global climate change, the attitudes, positions, and interests involved vary greatly, and international agreements will not be easy to forge or to enforce (Morrisette and Plantinga, 1991). However, the movement toward sustainable agriculture and land use in the humid tropics can serve as a focal point for shared actions based on common concerns. There is much room for collaboration and cooperation among the industrial nations of the north and the developing countries of the south in providing the people, the knowledge, the tools, and the political and financial support that are needed to transform the potential climate-related benefits of sustainable agriculture into reality.

Alternative Energy Sources

Many people in developing countries use wood and charcoal as their principal energy sources. Within the humid tropics, rising de-

mand has increased wood gathering. In these areas, alternate energy sources and national energy strategies that reduce the use of wood to sustainable levels are needed to help relieve the pressures on forested lands. More research should be devoted to fuelwood plantations; alternative sources of wood (for example, sawmill wastes) for charcoal production and more efficient production processes; improved kilns, stoves, and furnaces as well as solar technologies; and sustainable extraction practices.

In general, moist forests are less affected by fuelwood demand than drier forest types, but there are important exceptions. In Zaire, for example, fuelwood accounts for 75 to 90 percent of the total national energy budget, and fuelwood gathering is the leading cause of deforestation (Barbier et al., 1991). According to projections to the year 2000, 5.5 million ha of forestland in Zaire would need to be depleted each year to meet increasing fuelwood requirements (World Bank and United Nations Development Program, 1983; Ngandu and Kolison, Part Two, this volume). Forests near large urban areas and surrounding industrial development projects that require charcoal are especially susceptible to heavy exploitation. The Grande Carajas project in the eastern Amazon, for example, is projected to produce and consume 1.1 million metric tons of charcoal annually in its iron and cement operations. Eucalyptus plantations will meet some of this demand, but nearby forests are likely to be affected as well (Fearnside, 1987b; Gradwohl and Greenberg, 1988).