2

High-Skilled Immigration and Ideas in a World of Global Education and Research Collaborations

Dr. Richard Freeman, professor of economics at Harvard University and Director of the Science and Engineering Workforce Project at the National Bureau of Economic Research, opened the workshop with a keynote address that discussed how the worldwide expansion of education and knowledge affects the migration of high-skilled labor in the modern global economy. He emphasized the role that migration plays in the development and dissemination of ideas and knowledge on a global scale. The development and dissemination of science and engineering-based knowledge is critical to maintaining a competitive advantage in today’s economy. Moreover, international collaborations and dissemination of knowledge are more likely to occur when foreign-born researchers spend time in the United States, either as students or visiting faculty.

Collaborations among researchers in science and migration of ideas have increased over time, highlighting the need for decision makers to rethink high-skilled immigration policy in the United States. There has been rapid growth in the number of international students and authorship of scientific papers, especially among immigrants from China and other emerging economies. Given the importance of international students to fill domestic STEM jobs, Freeman focused on a number of areas that could improve U.S. competitiveness in the global talent arena, including maintaining the attractiveness of U.S. universities and re-aligning research funding toward physics, chemistry, and engineering. Increased university enrollments of both native- and foreign-born students drive knowledge creation, and international students who return to their home country aid in the dissemination of knowledge. Additionally, Freeman recommended incentivizing “translational research” to ensure that basic knowledge is translated into innovative activities that will spur economic growth. This chapter provides additional details from Freeman’s keynote address and the ensuing discussion.

The modern global economy depends on the production and dissemination of knowledge. University-based basic research and development work provides the stock of science and engineering knowledge that serves as the

foundation. Firm-based research and development uses this stock to create innovative products and process, and engineering and technology work by university graduates then turns this research and development into things that work, generating economic output.

In a knowledge economy, Freeman explained, globalization’s main impact is through the spread of knowledge via higher education, via the migration of students and highly skilled workers, and cross-border collaborations, rather than through trade and capital flows. Despite the “obsolete vision of the Washington consensus, World Bank, and International Monetary Fund,” the dissemination of knowledge is what is fundamentally changing the global economy according to Freeman.

One of the key factors in the global dissemination of knowledge is the huge increase in university enrollments worldwide. In 1970, 29.4 million students were enrolled in universities, with emerging markets accounting for 54 percent of that total and U.S. universities making up another 29 percent. By 2010, global university enrollment increased more than six-fold, to 177.6 million students, with emerging markets accounting for 76 percent of that total and the U.S. share shrinking to 11 percent. By 2025 university enrollments are expected to increase to more than 262 million students, with nearly all this growth from students in emerging markets. More than half of the growth will be from students in China and India. Between 1970 and 2010, the number of Chinese students getting a university education jumped from under 100,000 to 30 million, while the number of university students in India rose from 2.5 million to 20.7 million.

Accompanying this overall growth has been a jump in the number of students seeking to study abroad, a number that could rise from 4.5 million in 2012 to as many as 8 million by 2025. As the number of foreign students educated at universities in advanced economies rises, so too will the transfer of knowledge from advanced economies to emerging markets. Globalization of companies is also contributing to the spread of knowledge and ideas. It is uncertain whether it is more beneficial for countries to send more of their students overseas or to have companies like IBM come to your country, noted Freeman.

Modern technology spreads globally along three avenues. One is through consumption—the use of cell phones and the Internet being two examples. This is trade-related dissemination that is not connected to education or knowledge. A second avenue is via global chains of production, which again do not depend that much on education. Most of the assembly work in China, for example, is performed by rural migrants who are the country’s most poorly educated people. Although those products are assembled by poorly educated factory workers in China and elsewhere, the bulk of the value-added produc-

tion comes from efforts of high-skilled individuals, who are usually located in advanced economies.1

The third avenue for the spread of modern technology is via knowledge. The growth in world spending on research and development has increased more than the growth in the world’s gross domestic product (GDP). Much of this increase is due to China’s increase in research and development expenditures relative to its GDP which led to the corresponding increase in the number of science and engineering papers being published. China’s annual output of scientific and engineering papers more than quadrupled between 2001 and 2011, increasing at an annual rate of over 15 percent. In contrast, the global annual rate of increase in published science and engineering papers was 2.8 percent and the U.S. annual rate of growth was only 1.1 percent. While more than one-quarter of the world’s science and engineering papers are still published by U.S. researchers, China now accounts for 10.9 percent of total output. Another indicator of the growing presence of China in research and development circles is that while the United States’ share of researchers, science and engineering papers, and undergraduate and graduate STEM degrees awarded fell between 2000 and 2011, China’s share has increased significantly. India has also seen a substantial increase in the number of STEM degrees and scientific and engineering output. According to Freeman, the United States’ share of research is on a downward trend, not because U.S. scientists and engineers are performing poorly, but because more countries are involved in the dissemination of science. Although the United States only accounts for 6 percent of the world’s population, it produces 26 percent of its science and engineering papers.

One measure of China’s rising role in STEM fields is its rise in the number of PhDs granted. In 1986, Chinese universities granted 228 STEM PhDs, a number that reached nearly 28,000 by 2012. The only country whose growth in educational attainment can compare to China is South Korea, which underwent an astonishing transformation after the Korean War as it went from being one of the poorest countries in the world, to one of the best educated. The growth of the education sector in emerging markets is a direct result of students from those countries having access to the higher education systems of the United States and other advanced economies.

There is a “special relationship between the United States and China with regard to education.” The Chinese government has published data showing that the percentage of international students in the United States from China rose from 11.6 percent in 2007 to 28.7 percent in 2013. Of all Chinese students studying abroad, 59 percent study in the United States. In addition to post-

_________________________

1See also National Academy of Engineering, Making Value for America: Embracing the Future of Manufacturing Technology, and Work, Donofrio, N and K. Whitefoot, eds., Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2015.

baccalaureate degrees, there is some initial evidence that the Chinese government is now supporting undergraduates interested in studying in the United States.

International students, including those from China, make up an increasingly large fraction of graduate students, particularly in engineering fields. The U.S. National Science Foundation estimates that 63 percent of all post-doctoral STEM students working in U.S. universities are international students, and that 49 percent of international post-doctoral fellows received their PhDs in the United States. There has been a corresponding increase in the number of scientific papers coming from U.S. laboratories that have Chinese co-authors or coauthors from other emerging economies. These international students are not merely getting an education in the United States—they are also becoming U.S. STEM workers after graduation. In 2005, over a third of all STEM workers with PhDs were foreign born, with 64 percent receiving their PhD from U.S. universities. Over a quarter of U.S. STEM workers with Master’s degrees were born in another country and 15 percent of foreign-born STEM workers with Master’s degrees received that degree in the United States.

According to a different dataset, the percentage of foreign-born workers in U.S. STEM jobs increased from 11 percent to 19 percent between 1990 and 2011 for those with Bachelor’s degrees, from 19 percent to 34.3 percent for those with Master’s degrees, and from 24 percent to 43 percent for PhDs. International students are becoming an increasingly important source of workers needed to fill STEM jobs in the United States.

Freeman then discussed whether the increasing shares of international students in STEM fields represent a positive or negative development for scientific production. On the one hand, many of the most talented students from emerging economies are staying in the United States and other advanced economies after getting their degrees and advanced training, which could be considered a brain drain to their home country. On the other hand, many foreign students return to their home countries with new ideas, knowledge, and expertise that can increase innovation and economic growth. Even if they return to their home country, foreign-educated researchers are more likely to collaborate with international colleagues than domestically educated researchers. Even when they do stay in the country where they received their degrees, immigrants are likely to pass information and expertise back to their countries of origin through family and other connections and collaborations.

Returning to the U.S.-China relationship, Freeman noted that U.S. researchers accounted for 47.5 percent of China’s international collaborations in 2012, up from 35 percent in 1997, while Chinese researchers accounted for 16 percent of U.S. collaborations, up from 3.2 percent in 1997, as measured by the share of STEM articles that have international co-authors. China-based authors with U.S. experience are also more likely to co-author a paper with researchers

in the United States, suggesting that experience in the United States is a driving force for the increase in China’s STEM productivity. He said that Chinese scientists and engineers are surpassing their British and Canadian colleagues as the most common collaborators for U.S. researchers. He noted that the U.S. share of the world’s international collaborations has remained steady between 1997 and 2012 even as the rest of the world has been publishing more papers, producing more scientific research, and catching up to the United States in terms of productivity. “We are in a sense favored as collaborators,” said Freeman.

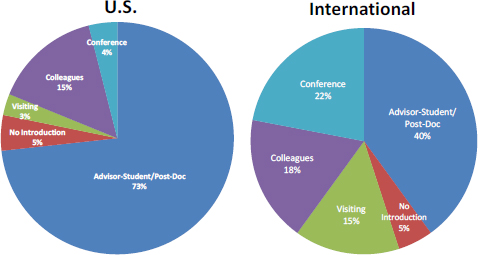

To better understand how international collaborations form, Freeman and his colleagues asked U.S. researchers about their collaborations. In the case of U.S.-based collaborations, nearly 75 percent are with former mentors/mentees and another 15 percent are collaborations with former colleagues. For collaborations with researchers based outside of the United States, 40 percent of U.S. researchers collaborate with former mentors/mentees while 37 percent met their foreign collaborators in conferences or while their collaborator was a visiting scholar. Meeting at a conference or when one researcher is a visiting scholar is much more important in establishing collaborations when one researcher is based abroad (Figure 2-1).

FIGURE 2-1 How collaborators first met. SOURCE: Online Survey of Corresponding Authors Published in 2004, 2007, and 2010 in the Web of Science Nano, Biotech, and Particle Physics subject categories with at least one U.S. coauthor, August 2012.

China’s rise as an important producer of STEM knowledge is also evident in the increase in citations from Chinese researchers. In 1998, the share of papers from researchers based in China was 2.5 percent and China’s share of citations in the literature was 1 percent. By 2007, Chinese researchers accounted for 9.1 percent and China’s share of citations in the literature had risen to 6.2 percent, even as the total number of papers rose from 667,000 to 900,000 papers. Over that same period, U.S. researchers’ share of the literature fell from 28.8 percent to 24 percent, and the share of U.S. citations fell from 42.1 percent to 34.7 percent. However, the quality of U.S. papers, as measured by average citations, remained high during this period. In addition, the impact factor for papers from Chinese authors who have spent time at either U.S. or other overseas institutions was higher than those from Chinese authors with no overseas experience.

The number of international students enrolled at U.S. institutions of higher education is sizeable and will continue to grow. These students produce a great deal of scientific knowledge, fill high-level positions, and make up a large proportion of STEM workers. To the extent that U.S.-trained students do better work and are more likely to get jobs in the United States than those trained in their home countries, it makes sense for the United States to adopt immigration policies that attract and retain international students.

Freeman also commented that unlike in other countries, biomedical research dominates the research portfolio in the United States. In 2011, for example, the United States spent 50 percent of its research funding on life sciences compared to 43.3 percent in the EU, 42 percent in Japan, and 26 percent in China.2 “The rest of the world is much more into physics, chemistry, and engineering,” said Freeman. There may be some value in shifting immigration policy toward students and workers in non-biomedical areas.

Finally, Freeman commented on the challenge of ensuring that U.S. taxpayer-funded research produces domestic economic benefits. To that end, Freeman proposed that the United States create new fellowships for students with advanced degrees or doctoral graduates specializing in the transformation of knowledge into improving U.S. productivity. For example, the U.S. might consider additional funding for scientists and engineers who specialize in translating basic research into transformative innovations and inventions, bridging the gap between fundamental and applied sciences.

_________________________

2U.S. data is available in the NSF publication, Federal Funds for Research and Development: Fiscal Years 2013-2015. See e.g., Table 33. Federal obligations for basic research by detailed field of science and engineering FYs 2013-2015 showing 51.4% of basic research funding in the U.S. is spent on basic life sciences. Available at www.nsf.gov/statistics/2015/nsf15324/#ch2 [Accessed December 11, 2015].

Clarifying some of the data he presented on Chinese students, Freeman said that 6 million out of 30 million Chinese college students earn Bachelor’s degrees each year. Philip Webre from the Congressional Budget Office then asked Freeman if he has any data on how well returnees to China fare in terms of competing for positions in academia. Webre was referring to the fact that there are more post-doctoral fellows in the United States than there are academic slots to fill. Freeman said that there are no data that he knows of to answer that question, but he did note that 75 percent of Chinese university presidents have been trained outside of China, with the bulk of them receiving their education in the United States. At the same time, individuals educated outside of China do not usually rise to very high positions in the Chinese government.

Ayse Alpay, an international PhD student from Northwestern University, asked Freeman if he had any data on what areas of research various countries are focusing on. Freeman said that he has recently started looking at that information for China, a country that is clearly putting an emphasis on chemistry, material sciences, and physics. He noted that Chinese funding for students is subject specific. In other words, a Chinese student studying in the United States that wants to switch fields cannot do so without permission from the Chinese government. Most other countries, except for the United States, follow this practice.

Peggy Wilson, from the Research Associateships Program at the National Research Council, asked Freeman if he had examined how research and development in federal labs is affected by scholars visiting from other countries. He replied that he has not and in return asked Wilson if she thought the proportion of research conducted by such scholars was larger than it is for students. It was Wilson’s guess that visiting scholars contribute less than graduate students. She added that Chinese participants in the NRC’s program, which has existed for about 55 years, say that they are more marketable at home once they have had a U.S. postdoctoral position, particularly at one of the national laboratories. Freeman said that studies at Oak Ridge National Laboratory indicate that 90 percent of the Chinese and Indian scientists who received their doctorates in the United States, still lived in the United States 7 years later.3 In contrast, only about 30 percent of Europeans remained in the United States in the same time frame. The Chinese students that Freeman has spoken to report

_________________________

3Finn, M. January 2014. Stay Rates of Foreign Doctorate Recipients from U.S. Universities, 2011, Science Education Programs, Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education. Available at http://orise.orau.gov/files/sep/stay-rates-foreign-doctorate-recipients-2011.pdf [Accessed on November 24, 2015].

that securing employment in the United States is a sign of prestige and success back in China.

Michael Clemens, from the Center for Global Development, asked Freeman if he could comment on how highly skilled migrants influence the productivity of less-skilled migrants. Freeman said he could only comment with regard to outcomes as measured by scientific papers. Data indicate that when individuals from different backgrounds collaborate, it is mutually beneficial and has greater impact than when individuals from similar backgrounds collaborate on a project. In the case of scientific papers and citations, Freeman hypothesized that papers published out of an international collaboration reach researchers in a broader range of social networks and disseminate knowledge more effectively. Another hypothesis would be that researchers from different countries, as opposed to those in close geographic proximity to one another, would have to engage in more conversation to reach a common ground and therefore be exposed to new ways of thinking about their research.

The final question in the discussion session came from Brad Wible of Science Magazine who asked if Freeman had seen any evidence that the Chinese government is starting to shift its focus from supporting applied or translational research to encouraging more curiosity-driven, investigator-initiated basic research that could lead to Chinese scientists winning the Nobel Prize, for example. Freeman said that was a difficult question to answer but that he has heard that in mathematics the Chinese are pushing to study more abstract concepts that could lead to Chinese scientists winning prestigious academic awards.