5

Competing for Students and Entrepreneurs

This panel session focused on the global competition for university students, entrepreneurs and STEM workers. The panel had three presenters. Lesleyanne Hawthorne, professor of International Workforce at the University of Melbourne, discussed the role that international students can play in meeting a country’s needs for skilled migrants. She stressed the importance of language proficiency and ensuring that students obtain degrees in areas where jobs are in demand in order to ensure good employment outcomes for the study-migration pathway. Jean-Christophe Dumont, head of the International Migration Division in the Directorate for Employment, Labor, and Social Affairs at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), discussed differences in investor visa programs in OECD countries. Lindsay Lowell, director of Policy Studies at Georgetown University’s Institute for the Study of International Migration, discussed the international competition for STEM workers. He showed that although the United States has remained the top destination for STEM workers, reduced funding for research and development may reduce the United States’ attractiveness. An open discussion, moderated by workshop planning committee member Paula Stephan, professor of Economics at Georgia State University, followed the presentations.

DESIGNER IMMIGRANTS? INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS AS POTENTIAL SKILLED MIGRANTS

Lesleyanne Hawthorne’s talk focused on study-migration pathways in which international students become skilled permanent workers in the country in which they are studying. When Australia opened its skilled migration pathway to international students, the country had approximately 150,000 foreign students enrolled in its universities. A decade after the new policy was implemented, there were 630,000 international students enrolled, making tertiary education Australia’s fourth largest industry and the top industry for the state

of Victoria. Foreign students are an attractive target for many countries, which can be seen in the way countries have developed, prioritized, and facilitated pathways by which foreign students can both study abroad and remain in their host country after receiving their degrees. Students’ young age, the fact that they are often self-financed and proficient in the host country’s language at graduation, make them attractive candidates to fill immigration spots. In addition, on graduation international students are likely to be acculturated and have training that matches the professional requirements of local employers.

One of the key benefits of attracting and retaining international students is the long length of their future productivity. The length of future productivity is potentially quite long for international students, especially if they can avoid spending 3 to 5 years on retraining themselves to work in their field. Temporary labor migrants average between 35 to 45 years of age. Skilled migrants may be younger, although it depends on the selection mechanism. For example, Canada has been admitting migrants with ages into their 50s. Countries that have conflicted or ambiguous views about immigration are often more open to admitting students.

OECD countries have been fortunate to attract the majority of international students; the majority of those students have come from Asia. Typically, the policy measures that OECD countries have adopted over the past decade or so have had the effect of expanding the scale at which international students, and particularly STEM students, come to OECD countries, but also to become more flexible about students' right to work and their right to stay in the country after obtaining a degree and seek employment in their fields. According to Hawthorne, international students want this opportunity. In a 1995 survey of about 8,000 international students in Australia, Hawthorne and her colleagues found that up to 78 percent of foreign students had come to Australia hoping to remain there after graduation, even though Australia’s policies at the time did not facilitate them remaining as migrants. The largest group of students who wanted to migrate at that time were from China, she added. The British Council student insight survey found that the option for migration was built into decisions about where to enroll in school, and the United Kingdom’s decision to shrink its study-migration pathway is reducing international student enrollment in British universities.

A decade ago, some 2 million students were studying abroad, a number that has likely grown significantly in recent years. The United States pioneered the study-migration pathway to increase the number of PhDs in STEM fields, and Australia’s study-migration programs began some 15 years ago. Australia’s program has had substantial variation in the number of students in the program, and the country has now learned how it has to change the pathway to continue producing a more consistent number of skilled migrants.

Other countries have followed the path set by the United States and Australia. Canada introduced its Canadian Experience pathway 5 to 6 years ago, but the issue today is to determine how large it should be. New Zealand also liberalized this pathway and now one-third of the international students who graduate in New Zealand remain there, although the process in New Zealand has many steps: students study, have work rights while they study, go through a study-to-work transition period, and then a temporary work-to-permanent resident transition. Singapore has been recruiting Australia’s international medical students in their final years of schooling. In particular, Singapore recruits Malaysian students who graduate from Australian medical schools.

Though most host countries assume that there are tangible benefits associated with boosting the numbers of international students, there have been remarkably few empirical, quantitative studies conducted to demonstrate and quantify those benefits. There has also been minimal research on former students’ outcomes relative to migrants selected offshore and new domestic graduates. Researchers have recently investigated the value of international students in countries where there have been greatly expanded flows, such Malaysia and the Netherlands. Policy discussions include whether students are opportunists, if they are really backdoor migrants, or if they are “dumbing down” skilled migration pathways.

Within 5 years of Australia opening its study-migration pathway, the country was able to select over half of its skilled migrants onshore. The bulk of these hires were students with a Master’s degree, and while in theory they were professionally qualified, many had gone into fields such as accounting and information technologies where they could add a lucrative two-year course on top of all sorts of other underlying degrees. From 2007-2011, this pattern changed. Vast numbers of international students were selected based on completing Bachelor’s as well as Master’s degrees. Their employment outcomes were excellent in fields with high demand (such as medicine, dentistry and pharmacy), but far weaker in fields which were over-supplied (such as business, IT, and accounting).

The scale of demand for entry into the study-migration pathway was large by the time Hawthorne and her colleagues were commissioned in 2006 to conduct a review of Australia’s skilled migration program.1 At the time of the study about one-third of all students from China who came to Australia migrated permanently and two-thirds of all students from India settled in Australia after graduation. Australia’s immigration department told her that internation-

_________________________

1Birrell, Bob, Lesleyanne Hawthorne, and Sue Richardson, Evaluation of the General Skilled Migration Categories, March 2006, Commonwealth of Australia Canberra. Available at www.flinders.edu.au/subs/niles-files/reports/GSM-2006_full_report.pdf [Accessed on November 23, 2015].

al students had a 99 percent chance of being selected as skilled migrants unless they failed a character or health test.

When Hawthorne and her colleagues conducted their study in 2006, they found that onshore former overseas students appeared to be doing quite well, with 83 percent of them employed in skilled positions within 6 months of graduating, about the same as for migrants selected from offshore, although there were differences based on the level of degree attained and field of study (Table 5-1). Surprisingly, migrants that arrived through the study-migration pathway whose language skills might lead to inferior labor market outcomes were actually doing well in Australia. For example, the employment rate for Chinese migrants selected onshore was 75 percent compared to 55 percent for those selected offshore. The same was true for migrants from other Asian countries, North Africa, and the Middle East. Indian migrants were doing very well regardless of whether they were selected onshore or offshore; fewer than 10 percent were unemployed. The same was true for students from English-speaking and European countries.

However, a key finding from this review was that despite their better outcomes in terms of employment, migrants selected via the study-migration pathway had salaries that were nearly $20,000 less than those of offshore arrivals. Also, study-migration pathway migrants reported lower job satisfaction than did their offshore compatriots and were less likely to be employed in their field of qualification.2 These findings, said Hawthorne, catalyzed a great deal of policy investigation and refinement.

Additional analysis identified a few important issues such as language proficiency and a large increase in enrollments without a corresponding increase in the quality and quantity of professors. The first key problem was related to English proficiency. While in theory, most universities required a specific level of proficiency on the International English Language Testing System exam to enroll, in practice some 40 to 43 percent failed to meet the stated cutoff. “Clearly, there was some conflicted selection going in by very profit-driven training organizations,” said Hawthorne. A second issue was the skewing of enrollments, where business and commerce, followed by accounting, dominated the enrollments. There were very large enrollments at private colleges that had only minimum quality assurance. At the time of the study, the state of Victoria had only five quality assurance inspectors for the entire state. According to Hawthorne, nobody anticipated the explosion of international students or the number of private colleges that would be interested in guiding people through a skilled migration pathway.

_________________________

2Ibid.

| Full-Time Employment by Qualifications Field | Bachelors | Master’s | PhD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medicine: | |||

| Domestic | 99.7% | 93.0% | 91.8% |

| International | 98.8% | 46.2% | 80.0% |

| Dentistry: | |||

| Domestic | 93.5% | 93.9% | |

| International | 95.5% | * | 60.0% |

| Pharmacy: | |||

| Domestic | 97.6% | 93.5% | 84.8% |

| International | 96.1% | 92.6% | 64.3% |

| Nursing: | |||

| Domestic | 94.0% | 95.2% | |

| International | 66.2% | 62.5% | * |

| Physiotherapy: | |||

| Domestic | 93.7% | 93.4% | |

| International | 66.7% | 84.4% | * |

| Business and Commerce: | |||

| Domestic | 76.4% | 91.5% | 88.5% |

| International | 39.7% | 41.4% | 68.2% |

| Accounting: | |||

| Domestic | 82.7% | 83.3% | 94.7% |

| International | 35.2% | 36.0% | 66.7% |

| Information Technology: | |||

| Domestic | 78.0% | 85.9% | 77.2% |

| International | 42.3% | 38.6% | 74.6% |

| Engineering: | |||

| Domestic | 86.4% | 88.2% | 86.7% |

| International | 43.6% | 37.6% | 79.3% |

| Education: | |||

| Domestic | 76.0% | 83.6% | 92.0% |

| International | 55.4% | 42.1% | 71.0% |

| Law: | |||

| Domestic | 83.9% | 91.5% | 84.9% |

| International | 50.3% | 41.2% | 71.4% |

Domestic compared to former international student residents in Australia (2009-2011).

Note: * = Omitted field, given minimal response rates.

SOURCE: Analysis of Graduate Destination Survey Data, 2007-2011.

Hawthorne recounted what she called her favorite story from the many interviews she conducted as part of this study. A college in Melbourne that had a large number of Indian and Chinese students was producing electrical linesmen when that occupation was removed from Australia’s in-demand job list. Overnight, that college changed its course offerings and started producing chefs, but with the same staff, the same students, and no kitchen. Due to the shortage of quality assurance inspectors, it took long time for the immigration department to catch on to what this school had done. In response to the proliferation of for-profit institutions with dubious credentials and poor student employment outcomes, Australia fine-tuned its study-migration program.3,4 The program now mandates higher language proficiency skills and allows fewer exemptions from testing. There was an improvement in quality assurance and removal of the poorly conceived migration incentives in the skilled occupation list, among others. The key changes involved greater reliance on employer or state sponsorship, increasing the number of points for greater English proficiency, and increasing the level of qualification needed for the study-migration pathway. The government also introduced a guaranteed right to stay and work after course completions for degree-qualified international students, with lengths of stay ranging from two years for those with Bachelor’s degrees to four years for PhD qualifications, in order to give those migrants time to position themselves for sponsorship by gaining work experience or improving their English proficiency, for example.

Hawthorne said that the initial decline in international student enrollment was significant, with the private vocational sector experiencing the biggest drop as expected. “But being the intelligent people they are, international students did a global scan, realized there were still excellent study-migration pathways, and they recalibrated enrollment decisions so that they moved back into the university sector aligned with areas such as nursing that are constantly in demand,” she explained. While it is too early to determine the full impact of the policy changes that occurred between 2009 and 2011, the salaries paid to onshore migrants and those who pass through the study-migration pathway were on par with each other.

To assess how employers regarded international students compared to domestic graduates in identical fields, Hawthorne and her colleagues analyzed data from 2007 to 2011 from Australia’s Graduate Destination Survey and looked at fields where there was sustained demand, an over-supply of labor, variable

_________________________

3Birrell, R., Healy, E., 2010. The February 2010 reforms and the international student industry, People and Place, 18(1):65-80.

4Koleth, E. 2009. Overseas students: immigration policy changes 1997–May 2010. Canberra: Australian Parliament, Department of Parliamentary Services. Available at http://www.aph.gov.au/binaries/library/pubs/bn/sp/overseasstudents.pdf [Accessed October 25, 2014].

demand, and modest demand. One key finding from this analysis was that employers prefer native or near-native speakers of English, regardless of whether they were domestic or international students. For both native Australians and international students with Bachelor’s degree qualifications, there were “extraordinarily strong outcomes” in high-demand fields such as medicine, dentistry, and pharmacy. Hawthorne noted that international medical students and nurses are proving to be a huge asset in building Australia’s medical workforce. However, for fields such as accounting, business, and information technologies, where there is a surplus of labor, international students are experiencing lower employment rates and lower salaries compared to native students. Outcomes for Master’s degree qualified international students in over-subscribed fields were even worse (see Table 5-1), with non-native English speakers experiencing far higher unemployment rates than for Master’s degree holders from English-speaking countries.

PhD holders, on the other hand, do well regardless of their country of origin, though there were some significant differences between employment rates for international and domestic students in certain fields, such as business and accounting and pharmacy. By the time they graduate, most PhD students have greater English proficiency and have been in Australia for at least 3 years. About a third of STEM skilled migrants are selected in Australia, both for temporary and permanent resident status.

The take-home lesson from the “Australian rollercoaster,” as Hawthorne called it, is that it is essential to be vigilant about monitoring outcomes from a study-migration pathway. This pathway is attractive to students, employers, and the education industry. In addition, to make sure the employment outcomes of students are good, English proficiency is important and employers want graduates to obtain degrees in STEM courses at a very high level. While the bulk of employers preferentially select skilled migrants who are onshore, STEM employers are more judicious about taking the most talented, no matter whether they are onshore or offshore.

INVESTOR VISAS IN OECD COUNTRIES

Discussing recent trends in investor and entrepreneur visas in OECD countries, Jean-Christophe Dumont said that it is not always easy to delineate between these two programs because investor programs often have job creation requirements, which implies that the candidate has some entrepreneurial skills. In his opinion, investor visa programs are the more interesting of the two because these programs are an active area of policy activity in OECD countries and because the number of entrepreneur visas has been fairly small in most countries.

With the exception of the United States, most of the investor visa programs in OECD countries are fairly new or have recently undergone significant

changes. There is also an emerging interest in startup visas, with Chile being the first country to introduce such a program. Though small, the Chilean startup visa program is receiving a great deal of attention worldwide because Chile not only grants the visas but also provides a small amount of capital to use in starting a business, access to local business people, and access to a startup incubator. In 2013, Canada introduced a startup visa program and recently awarded its first two visas through this program.

Countries have diverse objectives for their investor visa programs, including economic transformation, job creation, regional development, productivity gains, creating links to international markets, and stimulating local housing markets. The existing programs can be grouped into four categories. One category aims to stimulate employment and innovation and includes programs in the United States, the Netherlands, Germany, France, Chile, and Canada. The underlying idea behind these programs is that investors bring funds and commit to creating jobs. France’s program, for example, was introduced in 2009 and requires the visa holder to invest $10 million and to create at least 50 jobs. The U.S. AB-5 visa requires visa holders to invest $1 million, or $500,000 if the investment will be in a target employment area, and to create jobs. The Netherlands’s program requires an investment of €1.2 million, with an additional points-based selection system that assesses business skills and a number of other priority traits. In this program, selection is not based solely on the amount of capital that the investor brings but also on the capacity to manage those funds in a way that creates economic benefits for the host country.

The second category is the investment capital visa, which requires the applicant to invest money in a specific fund that invests in a country’s economy. This program provides no return on the investor’s money. New Zealand, Australia, Britain, Ireland, Spain, and Korea have these programs. New Zealand’s program has some flexibility regarding the amount to be invested depending on the investor’s experience in running a business.

A third category is the donation visa, where migrants either donate a large sum of money or make a large purchase of sovereign bonds in exchange for a visa. Ireland, Spain, and Greece are examples of countries with this type of program. Spain requires a $2 million purchase of Spanish bonds to get a visa, while Greece requires a larger purchase of public debt for its visa.

The fourth category requires the investor to make a large investment in housing or other assets in exchange for a visa. Ireland, Spain, Portugal, and Greece have programs that require the investor to build a new house rather than buying an existing house. Greece also has a program in which a €100 million investment in the country procures a visa regardless of the investor’s age or experience.

While most countries are constantly refining these programs, they are doing so with few systematic evaluations. The goal of all of these programs is to

provide economic benefits for the host country; however, because no country is collecting data, it is difficult to determine whether that is the case. Since each country’s program is unique, cross-country comparisons are difficult. Dumont’s research has looked at the large variation in the minimum required investment, as well as the number of years it takes for the investor to obtain permanent residence in the country.

The data show differences across countries, with larger investments generally yielding shorter times until permanent residence. Some programs are flexible, such as New Zealand’s, which requires 1.5 million New Zealand Dollars with a residency requirement of 140 days over three years, or 10 million New Zealand Dollars with a residency requirement of only 44 days. Estonia requires a minimal investment but it must be accompanied by an approved business plan. The United States requires an investment of under $1 million but that investment must generate at least 10 qualified jobs over a 2-year period. France is notable because it requires the largest investment, but it still takes 10 years to gain permanent residence.

There can be a mismatch between migrants’ and the destination countries’ expectations of investor visas. Investors may be motivated to move to a safe destination country or they may be looking for better access to tertiary education for their children. It may be that getting a different passport provides a type of insurance that will allow the migrant to move around the world more easily and safely. Making an investment may be the path of least resistance to acquiring a visa, which means that migration is driving investment, not vice versa.

In closing, Dumont posed a number of policy issues that need to be addressed with these programs. There is the issue of public perception—is the program adding value or just selling residency and citizenship? There are selection problems because immigration officers may not be qualified to assess investment plans or to monitor their successful implementation. While the point of these programs is to produce some economic benefit for the country issuing the visa, it is hard to judge the success of these programs. It may not be cost-effective for countries to conduct any cost-benefit analysis of these visas given the small number of visas awarded. There are also other externalities, particularly in the EU where a permanent residence visa provides access to every member country. In the end, a major question is whether these individuals go through this channel because they see an investment opportunity or because it is the easiest way to gain residency.

COMPETING FOR FLOWS OF STUDENTS

Lindsay Lowell discussed the global competition for international students to fill high-skilled jobs. But, before discussing competition for students, he made

several points. First, when policy makers in the United States talk about high-skilled immigration, they really mean STEM workers with graduate degrees. Evidence suggests that the United States does not restrict the number of STEM workers with graduate degrees, given that the proportion of foreign-born STEM PhD holders has doubled (to 50 percent) in two decades and the proportion of master’s degree holders has increased 30-40 percent in the same period of time. Increasing the number of STEM workers may not increase innovation, demand, and economic growth when the number of immigrants rises substantially.

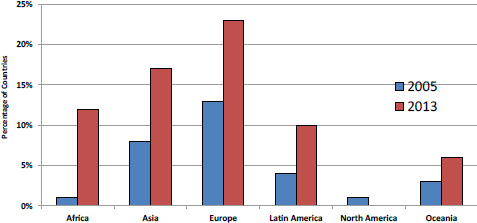

In addition, while some other countries are competing for workers, large competitors, such as the United Kingdom and Singapore, are scaling back their programs. Competitive policies in Sweden and Norway, for example, attract a small number of the most qualified skilled migrants. According to a 2013 United Nations survey, most countries have expressed a desire to raise skilled immigration although the United States and Canada are not among those (Figure 5-1).

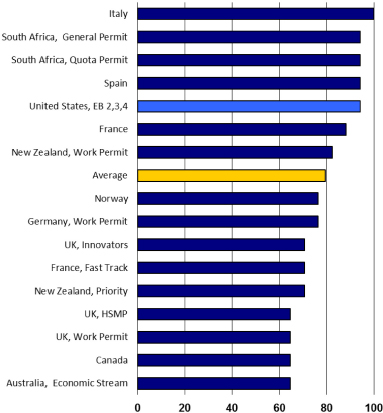

According to a number of criteria used to gauge the restrictiveness of a country’s immigration policies, the United States’ visa policies are relatively restrictive compared to other countries (Figure 5-2). Australia, for example, had less retrictive policies for attracting high-skilled migrants while Italy had the most restrictive policies. Many nations’ policies have changed over the past decade. Although the United States does not have a particularly attractive policy regime for recruiting skilled migrants, skilled migrants still want to come to the United States.

FIGURE 5-1 Percentage of nations reporting policies to raise highly skilled immigration. SOURCE: United Nations 2013, World Population Policies Report.

FIGURE 5-2 Ranking of the index of controlled and competitive permanent skilled worker programs, from most to least restrictive. Note: The criteria used to determine restrictiveness include: hard numerical caps, strict labor market test, extensive labor protections, enforcement mechanisms, limited employer portability, restriction on dependents/working spouse, and limited permanency rights. These criteria are converted into an index with the most “controlled” country given a value of 100. SOURCE: Policies and Regulations for Managing Skilled International Migration for Work, B. Lindsay Lowell, 2005.

Students are a major source of STEM workers, and international student enrollments in STEM subjects are increasing substantially. China and India are experiencing rapid growth in the production of STEM graduates, though quality is an issue. The U.S. share of international students has dropped from about one-quarter of all students to one-eighth, but the absolute number of enrollees has risen significantly, from 500,000 to over 800,000. “If we were to retain our share over an expanding enrollment of international students, the number of students in the United States would grow very rapidly. Do we have the capacity and can we deal with the issues that Australia dealt with?” asked Lowell, referring to the rise of low-quality diploma mills.

An analysis of OECD data on the enrollment patterns from 100 countries to the United States showed that as enrollments in tertiary education increase in a source country, the more migrants that country sends to the United States. This analysis also found that as tertiary enrollments in a different country increased, fewer migrants came to the United States. As an example, he noted that as the number of Indian students enrolling in U.K. institutions rose, the number of Indians coming to the United States fell. “So there is competition,” said Lowell. “You can see it in the data.”

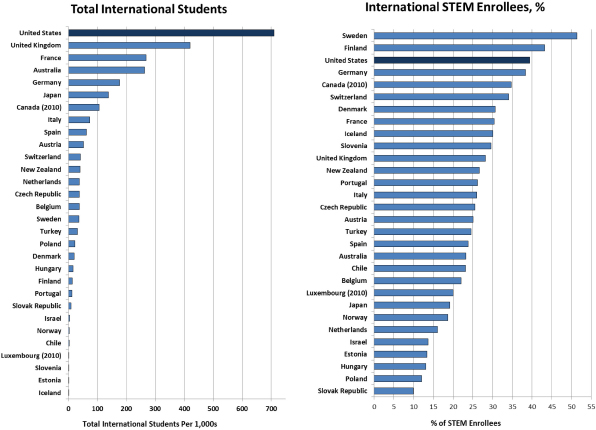

Immigration policy is just one of a variety of factors that affects migration to the United States, but immigration policy seems to have only a marginal effect on the number of immigrants. For example, visa rejection rates have a fairly small relative impact on the number of students coming to the United States relative to differentials in economic growth. If immigration policy was an important component in determining which universities foreign students attend, the United States would not have received two-thirds of the world’s college educated migrants in 1990 and 2000, and the United States would not be ranked first by a substantial margin in the number of all students and ranked third in the percentage of those students who were pursuing STEM degrees (Figure 5-3). After STEM fields, business was the most popular subject of study for international students in the United States during that period. The impact of a large number of business students may be substantial on growth, because it is often the business majors who take advantage of ideas and bring them to market, according to Lowell.

Another indication of how well the United States is competing for international STEM workers comes from data on the number of high-skilled foreign born workers in the 20 leading destination nations. From 1980 to 2010, the percentage of high-skilled migrants living in the United States relative to the other top destinations rose from 46 percent to 49 percent, even as the total number rose by more than four-fold. Similarly, data from the World Intellectual Property Organization showed that from 2001 to 2010, the flow of inventors around the world was dominated by flow into the United States,5 while OECD data shows that the United States remains the main destination for international authors of scientific papers.6

_________________________

5CDIP (Committee on Development and Intellectual Property). 2013. Study on Intellectual Property and Brain Drain: A Mapping Exercise. Geneva: World Intellectual Property Organization. Available at http://www.wipo.int/edocs/mdocs/mdocs/en/cdip_12/cdip_12_inf_4.pdf [Accessed October 25, 2014].

6OECD. 2013c. OECD Science, Technology and Industry Scoreboard. Paris, France: OECD Publishing. Available at http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/science-and-technology/oecd-science-technology-and-industry-scoreboard-2013_sti_scoreboard-2013-en [Accessed October 25, 2014].

FIGURE 5-3 The number of international students in a given country in 2011 (left) and the percentage of international STEM enrollees in 2011 (right). SOURCE: OECD Science, Technology and Industry Scoreboard 2013; OECD calculations based on OECD (2013), Education at a Glance: OECD Indicators.

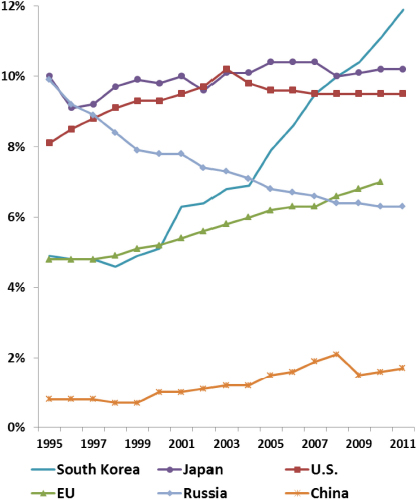

FIGURE 5-4 Researchers as a share of total employment in selected countries/regions: 1995-2011. Note: National Science Foundation, Science and Engineering Indicators 2013. SOURCE: OECD, Main Science and Technology Indicators (2013/14 and earlier years).

At present, the United States is the leading employer of researchers in terms of absolute numbers, and trails only South Korea and Japan in terms of researchers as a share of total employment (Figure 5-4). These are indicators, said Lowell, of the U.S. capacity to be competitive going forward. While wage growth in the United States for STEM workers has been fairly flat over the last 5 to 6 years, STEM wage growth in major competitor countries in Europe has not risen substantially faster over that same time period.

While the United States has done a good job of attracting a large number of immigrants, the evidence of its ability to select the best skilled migrants is

mixed. Looking at unemployment rates and employment rates of the highly skilled, the United States does better than most European countries. The United States also does well in terms of retention rates, another factor that would be important to a potential migrant. However, the share of foreign-born individuals in the United States who have gone to college is less than that of many other countries, which is a sign that the United States is not particularly selective in choosing which migrants get to work in the country. Ireland, Canada, Great Britain, and Norway, among others, are more selective than the United States in admitting migrants who are better educated than the native population, explained Lowell. In addition, migrants who come to the U.S. hold a much smaller percentage of U.S. patents than do immigrants to other countries, particularly for the top five percent of cited patents. Holders of H-1B visas, many of whom changed their status from student visa holders, earn 5 to 10 percent less than natives in the same jobs.

There appears to be a tradeoff between increasing the number of migrants from a particular country and the skill level of those immigrants. As the volume of emigrants from a country goes up, on average the proportion of professionals goes down. Similarly, every 10 percent increase in the number of H-1B visa holders is accompanied by a corresponding five percentage point drop in their relative earnings advantage. Also, as the number of foreign-born STEM workers has risen in the United States, the proportion of foreign-born Nobel Prize winners has fallen, perhaps due to globalization and a reduction in the selectivity of those who migrate. The biggest challenge for the United States to remain competitive for STEM workers going forward is the decline in research and development funding in the United States. The declining funding picture has led to a decline in potential earnings for STEM workers.

In summary, Lowell said that the global competition for high-skilled workers is not all about immigration policy and that the United States retains a competitive edge with its economy, universities, and job opportunities. The growing global supply of STEM workers means that today’s competition is for the most talented individuals and that even small nations can and are competing. While immigration policy is not the only factor influencing this competition, it does have an impact and the United States needs to reform its policies in a way that favors neither a “fewer and harder” or “more and easier” approaches, but rather takes a “generous and targeted” approach in terms of numbers and selectivity.

Panel moderator Paula Stephan opened the discussion by noting that bringing in migrants as students avoids some, though not all, of the mismatch issues that Graeme Hugo discussed in the previous panel session. She also re-

marked that the United States has seen a huge influx in international self-financed Bachelor’s degree candidates, in part because universities are increasingly relying on the tuition money from international students to fund their operations. The United States needs to be careful that it does not experience a corresponding growth in the types of problems seen in Australia discussed during Hawthorne’s presentation. Universities can, however, play a role in selecting the most talented students.

Stephan also pointed out that the huge growth of PhDs bestowed in STEM fields did not come from the top U.S. universities but from institutions in the second and third tiers that expanded when federal funding for research was growing at a considerable rate. It is important to consider how a decline in federal funding will impact the attractiveness of U.S. institutions to the most talented students, given that one of the most important reasons that they want to come to the United States has been career opportunities.

Jennifer Hunt continued the discussion by asking Hawthorne if she could explain why it appears that so few skilled Indians are migrating to Australia. Hawthorne replied that India has been a huge source of skilled migrants for Australia for many years. Indian migrants have dominated the field of medicine for 30 years and engineering for the past 20 years, for example. Until Australia opened the study-migration pathway, there were few Indian students in Australia. Today, Indian students outnumber Chinese students.

Madeline Zavodny wondered if China’s one-child policy is going to have an impact on migrants when their parents reach the age where they start depending on them for financial and emotional support. Hawthorne said that this is a very important issue and in Australia the impact is already being felt. She explained that under Australia’s family reunification program, Chinese students started applying in large numbers to sponsor their parents for immigration almost as soon as the students became permanent residents.

In response to a question about immigration policies that might address the so-called “skills gap” for STEM workers who are not professors, Dumont said that assessment and recognition of qualifications prior to arrival plays an important role in this regard in both Germany and Australia. Given that degrees and technical qualifications are not always equivalent between countries, it is important to work with employers to educate them about the true value of diplomas and technical qualifications that international workers possess.

Stephen Merrill noted that the United States appears to be quite interested in various types of entrepreneurial visas, despite their well-documented issues, and asked Dumont if he anticipated that other OECD countries will have the same type of problems should these visas become more common. Dumont replied that the greatest difficulty with entrepreneur visas was assessing the likelihood of success for an entrepreneurial project. Banks have the capability to make that assessment but immigration officials do not, and as a result, the

tendency has been for countries to be fairly restrictive in issuing entrepreneur visas. Dumont said that many East European countries were granting entrepreneurial visas, but the misuse of these visas has been noted by other countries. The bottom line is that he does not expect the number of entrepreneurial visas to ever be high. Hawthorne then commented that in New Zealand, entrepreneurial visas holders have been purchasing property and inflating prices beyond the reach of locals. She also noted that when she looked at Australian data, many of the Chinese entrepreneurs entering the country had poor English skills and had difficulty finding a domestic manufacturing partner. As a final comment, Dumont added that OECD data show that while immigrants with entrepreneurial skills and business projects can be successful in developing businesses, the success rate of foreign-born entrepreneurs is less than that for native-born entrepreneurs.

This page intentionally left blank.