6

The Effects of Immigration on Innovation and Labor Markets

This panel session discussed the impact of immigration on labor markets and innovative activity in a variety of different countries. Three speakers made presentations: Herbert Brücker, professor of Economics at the University of Bamberg and head of the Department for International Comparisons and European Integration at the Institute for Employment Research in Nuremburg, gave his perspective on how high-skilled migration can affect labor markets in Europe; Daniele Paserman, professor of Economics at Boston University, discussed the effects of high-skilled immigration on productivity and labor markets from Israel’s experience; and William Kerr, professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School, discussed the role of international migration on U.S. innovation. William Lincoln, assistant professor of International Economics at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, commented on the three presentations. An open discussion, moderated by planning committee member Ellen Dulberger, then followed.

HIGH-SKILLED MIGRATION AND IMPERFECT LABOR MARKETS

Herbert Brücker’s presentation focused on European labor markets. Over the past decade, high-skilled migration has increased substantially in Europe, particularly in the United Kingdom, Germany, and the Scandinavian countries, and at a slightly lower rate in Italy and Spain. In Germany, the share of recent migrants with a university or equivalent degree has doubled in 10 years. Although high-skilled immigration has more public support than immigration of less-skilled individuals, there are widespread concerns that if left unchecked, high-skilled immigration could cause unemployment to increase and reduce wages of native-born workers in Germany.

Brücker’s research examines the impact that high-skilled migration has on wages and employment in a setting with imperfect labor markets, using a cross-sectional approach that assumes that differences in the labor market and

workforce institutions affect how wages and employment respond to labor supply changes that accompany immigration.1 His presentation focused on three countries: Denmark, Germany, and the U.K. as representatives of three different types of European welfare states (Table 6-1). Denmark represents the so-called Flexicurity model, which has moderate employment protection, extremely high union density, coverage of collective wage contracts and unemployment benefits, intermediate levels of product market regulation, and high trade exposure. Germany is an example of the Continental European model, which has with high employment protection, relatively low union density but high coverage of collective bargaining, relatively high unemployment benefits, high product market regulation, and high trade exposure. Great Britain and its Anglo-Saxon model, which is perhaps the most similar to the U.S. model, has low employment protection, moderate union density and low collective bargaining coverage, relatively low unemployment benefits, low product market regulation, and low trade exposure. In each of these three countries, collective wage bargaining in one way or another affects the way society overall and wages in particular respond to unemployment and labor supply shocks.

TABLE 6-1 Institutional Indicators for Denmark (DK), Germany (DE), and the United Kingdom (UK)

| DK | DE | U.K. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Employment Protection Index | 1.50 | 2.12 | 0.75 |

| Principal Bargaining Level | Industry | Industry | Firm |

| Collective Bargaining Coverage in % | 82 | 63 | 35 |

| Union Density in % | 68 | 19 | 27 |

| Minimum Wage | No | No | Yes |

| Net Income of Unemployed in % of Net Income of Employed Households | |||

| Single, No Children | 83 | 59 | 55 |

| Married, Two Children | 88 | 80 | 77 |

| Product Market Regulation Index | 1.06 | 1.33 | 0.84 |

| Import Penetration in % of GDP | 54 | 44 | 31 |

| Export Propensity in % of GDP | 50 | 46 | 29 |

| Net Migration 1990-2010 in % of Pop | 4.3 | 8.6 | 4.2 |

Source: OECD (2014), Venn (2009), WDI (2014).

_________________________

1Brucker, H., Jahn, E.J., Hauptmann, A., Upward, R. 2014. Migration and Imperfect Labor Markets: Theory and Cross-country Evidence from Denmark, Germany, and the U.K., European Economic Review, 66:205-255.

Brücker’s work examines the hypothesis that the impact of different migrant skill groups may vary across countries depending on these institutions. Most of the literature on how immigration affects wages and employment either ignores unemployment or assumes that labor supply is inelastic and that labor markets are perfect. Also lacking have been studies that consider wage and employment response to migration simultaneously in a joint framework. Brücker’s theoretical approach has been to use a wage-setting framework that assumes that wages respond imperfectly to changes in the unemployment rate. In this framework, the conventional labor supply curve is replaced by a wage-setting curve. Consequently, wages can respond to “sticky” labor market shocks. He added that measuring the elasticity of the wage-setting curve can capture differences in institutions such as collective bargaining across countries. The demand side is derived from a traditional production framework.

The empirical framework that Brücker employs is to group the workforce by education, work experience, and the relative number of native and migrant workers using micro data collected by the governments of the three countries. One challenge is defining who is a high-skilled migrant, especially when using data from multiple countries. To harmonize categories, Brücker and his colleagues used characteristics such as years of schooling and degrees, and he noted that extensive testing showed these methods to be robust.

Once the labor force groups are in place, the first step in the analysis is to estimate wage-setting equations by assuming that wage-setting curves vary across education groups. Assuming that firms adjust employment once wages are fixed, Brücker’s team then estimates a bundle of labor demand equations that yield the elasticities of substitution between natives and immigrants, work experience and education groups. In all of their estimates, they apply an instrumental variable approach to address the potential endogeneity of wages and employment. Putting all of these pieces together then enables Brücker and his colleagues to simulate the wage and employment response to migration.

Using this framework, Brücker found that elasticities differ across countries, with Britain having the most flexibility in setting wages for both natives and immigrants. More importantly, the analysis reveals different response patterns for the different skill groups. In the United Kingdom and Germany, the elasticity of the wage-setting curve is substantially higher in the high-skilled segment compared to the medium- and low-skilled groups, with the opposite holding true in Denmark—wage flexibility is lowest in the high-skilled group—which Brücker characterized as unusual. One explanation for the result in Denmark is that there is a large share of public sector employment filled by high-skilled workers, particularly women in the education sector. Another explanation may be that labor union density is higher in Denmark for high-skill individuals compared to other groups in the labor market, which could increase pay.

One interesting finding was that migrants and natives are imperfect substitutes for one another, which supports findings made by other researchers. Moreover, the small elasticity of substitution between natives and immigrants implies that the effects of high-skilled migration are concentrated on a very small labor-market segment. “So if the high-skilled segment of immigrants in the labor market is relatively small, and if you put a high-skilled shock on the labor market, and if you have a low elasticity of substitution, then you have a huge wage effect for high-skilled migrants in the labor market, and if you have a higher elasticity of substitution then it’s more equally spread over the labor market,” explained Brücker. He noted that the elasticities of substitution across experience and education groups display no country-specific patterns and are similar to those found in other studies.

With the calculated parameters in place, Brücker and his colleagues use these parameters to estimate a short-run scenario in which the physical capital stock is fixed and a long-run scenario with a fixed capital-to-output ratio. The short-run aggregate wage reduction in response to immigration is higher in the United Kingdom while the short-run aggregate unemployment rate increase is higher in Germany and Denmark. However, the degree of response depends critically on the elasticity of the capital stock. In the long run there are no wage effects because of adjustments in capital stock. Moreover, in the long run, high-skilled migration actually reduces the unemployment rate in Britain substantially, though it continues to increase the unemployment rate slightly in Denmark and Germany. In the long run, natives in all three countries benefit from high-skilled migration; earlier immigrants are the losers. In addition, compared to immigration at the average skill level of the labor force, high-skilled migration reduces the unemployment rate in Britain and Germany, but increases the unemployment rate in Denmark as a consequence of the low wage-flexibility in the high-skilled segment there.

Brücker noted that the aggregate impact of high-skilled migration is larger because of the large impact that these workers have on productivity of workers at all skill levels. More interesting, though, are the implications for native and immigrant workers. In the long-term, native workers in the United Kingdom benefit more from high-skilled migration than from average-skilled migration, while earlier immigrant workers in Britain lose more in terms of wages but less in terms of employment opportunities. In Germany, native workers benefit more from middle-skilled immigration than from high-skilled migration, while high-skilled migration mitigates the adverse impact on migrant workers. He explained the latter by explaining that in Germany, the average qualification level of the native workforce is higher than it is in the migrant workforce, so native German workers compete more with high-skilled migrants. The effects of high-skilled migration on native Danish workers of any skill level are ambiguous, but migrant workers re-

gardless of skill level lose more from high-skilled migration, both in terms of wages and employment opportunities.

“Our findings suggest that the labor market effects of high-skilled and other immigration depend on the responsiveness of wages to labor supply shocks and the elasticities of substitution between different groups in the labor market, and that the responsiveness of wages and the elasticities of substitution vary across countries, reflecting institutional differences,” said Brücker in summarizing the results of these analyses. The results for the United Kingdom compared to those for Denmark and Germany suggest that higher wage flexibility increases the benefits of migration, at least over the long run. Moreover, as long as wage flexibility is higher in the high-skilled segments of the labor market, high-skilled immigration can reduce unemployment (in the best scenario) or have less of a negative impact on employment (in the worst scenario) compared to medium- and low-skilled immigration. Denmark’s results are likely to be the exception rather than the rule, Brücker added.

In addition, these analyses showed that native workers do benefit from immigration as long as the elasticity of substitution between immigrants and natives is low and the skill-structure of immigrants is different from the native population. Brücker pointed out that the total gains from immigration can be enhanced and inequality reduced by developing labor market policies that attempt to increase wage flexibility, through immigration policies that target immigrants in flexible labor market segments, and by integrating policies that attempt to increase the elasticity of substitution between native and foreign workers. Overall, high-skilled immigration increases the total welfare of a country if wage flexibility is high in the high-skilled segment.

In closing, Brücker noted that this analysis has limitations, the primary one being that it is limited to three European countries; therefore, it is mere speculation to think about its implications for the United States. Assuming that the United States is more similar to the United Kingdom than to Germany and Denmark, it is likely high-skilled immigration reduces unemployment in the United States. If high-skilled immigrants increase innovation and productivity in their adopted country, all workers benefit.

THE ISRAELI EXPERIENCE WITH HIGH-SKILLED MIGRATION

According to Daniele Paserman, Israel is often known as the “startup nation” because it has outpaced every industrialized country in terms of venture capital investments per capita. Israel outranks every country except for the United States and China in terms of the highest number of companies listed on the NASDAQ stock exchange, another measure of entrepreneurial ability. The

authors of the best-selling book Start-up Nation2 credit immigration as one of the two major factors that have contributed the most to Israel’s economic growth.

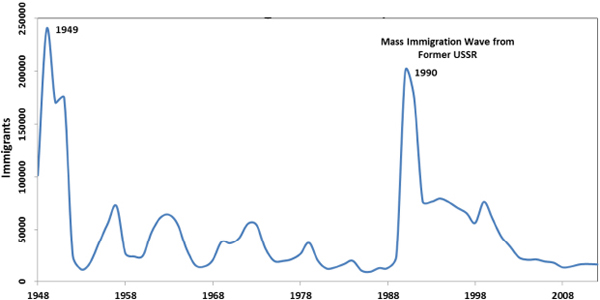

That Israel is a nation of immigrants is clear in terms of both absolute and relative numbers (Figure 6-1). At various times in its history, Israel has taken in waves of immigrants, starting with the country’s founding in 1948 through the huge wave of immigrants from the former Soviet Union following the collapse of the Berlin Wall. Around 200,000 immigrants entered the Israel between 1990 and 1991, followed by several successive years in which immigration numbers were approximately 60,000 to 70,000 per year. In relative terms, the 1990-1991 immigration wave alone accounted for 3.5 to 4 percent of Israel’s entire population, and immigration over the 1990s increased Israel’s population by about 20 percent overall, a level of immigration that Paserman said was comparable only to the mass migration to the United States that occurred at the turn of the 20th century.

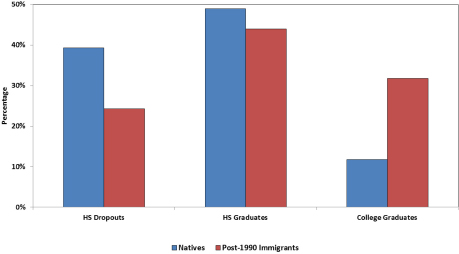

One unique aspect of the immigration wave of the 1990s is the immigrants’ high level of education compared to that of those who were already living in Israel (Figure 6-2). In the 1990s, about 12 percent of native-born Israelis had a college degree, while over 30 percent of the post-1990 immigrants had a college degree. “This was an overwhelmingly highly skilled group of migrants,” said Paserman, who added that Israel’s gross domestic product has grown at an average of 4.6 percent per year since the 1990s, compared to 2 percent per year in the United States.

In contrast to most countries, Israel has an almost completely open immigration policy. The Israeli Law of Return guarantees that anyone who is Jewish is free to immigrate to the country and become a citizen immediately, with Jewish defined as having one grandparent who is Jewish. Moreover, new immigrants receive generous subsidies including a cash allowance for 6 months, incentives such as rent or mortgage subsidies, access to free intensive Hebrew classes, and even tax benefits and tuition breaks. Scientists receive additional benefits, including job counseling and enrollment in an employer-employee matching program. Employers receive subsidies up to $46,000 over a 3-year period for hiring immigrant scientists or PhD researchers. These benefits apply to returning Israelis as well. “Many of these benefits are also designed to encourage return migration,” said Paserman.

Many of these policies were already in place in the 1990s and they probably contributed at the margins to the huge wave of immigration that took place during that decade. The main driving force, though, was the collapse of

_________________________

2Senor, Dan., S. Singer. 2009. Start-up Nation: The Story of Israel’s Economic Miracle. New York, NY: Hachette Book Group.

FIGURE 6-1 Immigration to Israel in absolute numbers, 1948-2012. SOURCE: Israel Central Bureau of Statistics.

FIGURE 6-2 Educational attainment in Israel by immigrant status. SOURCE: Israel Central Bureau of Statistics.

the Soviet Union and the uncertain economic prospects and security situation in Russia. As the 1990s progressed, immigrants became less skilled, and when Israel’s internal security situation began to deteriorate in 2000 while Russia’s economy was improving, migration from the former Soviet Union largely came to a halt. “So I think it is interesting to look at these policies, but we shouldn’t exaggerate the role that these policies have in attracting immigration,” said Paserman.

Focusing on the 1990s mass migration episode, Paserman then discussed how this influx was absorbed into the Israeli economy and its effects on the labor market and productivity in manufacturing. Not surprisingly, many of the immigrants struggled to find jobs that were commensurate with their skills. One survey of Soviet immigrants that oversampled engineers found that while 84 percent of the survey sample had worked as engineers in the former Soviet Union, only 11 percent of these individuals were employed in high-skill occupations within the first year of arrival in Israel, and only 36 percent were employed in high-skill occupations 5 years later.3 Paserman noted that natives with college degrees are overwhelmingly employed as scientists or in other white collar jobs, whereas the 1990s immigrants mainly worked in blue collar jobs.

The immigration wave of the 1990s was associated with a short-term drop in the wages of native workers in occupations with high concentrations of immigrants: a 10 percent increase in immigrant share was associated with a 3

_________________________

3Weiss, Y., R. M. Sauer, and M. Gotlibovski. 2003. Immigration, search, and loss of skill, Journal of Labor Economics, 21(3):557-592.

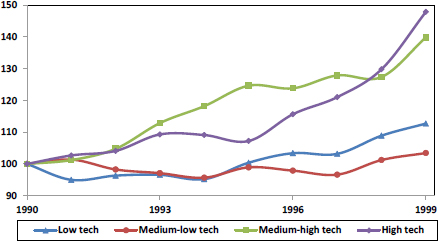

percent drop in native wages, though the effect dissipated after five to ten years.4 There is some debate, however, about the nature of this relationship, with some scholars arguing that there was no casual effect of immigration on native wages.5 Output per employee in the manufacturing sector, which employed a disproportionate share of immigrants, far outpaced that for the rest of the private sector in Israel following the start of the 1990s immigration wave. This growth in output, he added, was driven largely by medium-high and high-tech industries (Figure 6-3). Again, he noted, there is a debate as to whether immigration was the cause of this increase in productivity, particularly given that manufacturing productivity was increasing elsewhere in the world during this same period. U.S. manufacturing productivity growth, for example, jumped from 2.8 percent in the 1980s to 4.7 percent in the 1990s.

Immigrants took jobs across a wide range of industries, and as the decade progressed, they shifted more toward high-tech industries in a manner that correlates to some extent with the growth of the electronic components industry in Israel. In 1993, 93 percent of the immigrants were employed as production workers, and while 13 percent of Israel’s total workforce was comprised of immigrants, only 7.4 percent of Israel’s scientists were recent immigrants. By 1997, that gap had closed, with the share of immigrants working as scientists within the manufacturing sector mirroring their proportion of the total population, and the percentage of recent immigrants employed as production workers falling to 81 percent.

Despite the macroeconomic impact of immigration on productivity, there was no evidence that immigrant concentration is correlated with productivity at the individual firm level. “The bottom line is that if you regress output per worker or total factor productivity or other measures of productivity against the share of immigrants in a firm or an industry, you typically find zero effects,” said Paserman, who added that if anything, there might be a slightly negative correlation driven by the presence of immigrants in low-tech industries. These results are robust to different measures of productivity. One explanation is that high-skilled immigrants were largely employed in low-skilled jobs thus there would be no reason to expect a larger share of immigrants to lead to higher productivity. Another possible explanation is that cultural and language barriers impede assimilation. Finally, Paserman said that there are some general lessons to be learned from Israel’s experience. One is that cultural, language,

_________________________

4Cohen-Goldner, Sarit and Paserman, M. Daniele. 2011. The dynamic impact of immigration on natives’ labor market outcomes: Evidence from Israel. European Economic Review, 55(8):1027-1045.

5Friedberg, Rachel. 2001. The impact of mass migration on the Israeli labor market, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116(4):1373-1408.

FIGURE 6-3 Manufacturing output per worker by tech sector from 1990-1999 (1990=100). SOURCE: Paserman, IZA Journal of Migration 2013 2:6.

and professional barriers are real challenges for immigrants. Another is that not all human capital is transferable. Immigrants are not always more driven, ambitious, and successful than the native population. As the number of immigrants increase, the probability of getting the most talented individuals decreases.

IMMIGRATION AND U.S. INNOVATION

The United States is a land of immigrants, though perhaps not to the same extent that Israel has become over the past 60-plus years, said William Kerr. Nonetheless, legal immigrants made up 16 percent of the U.S. workforce in 2008 and have accounted for 29 percent of the growth of the U.S. workforce since 1995. This is particularly true in STEM fields. The 2010 U.S. census found that 25 percent of the Bachelor’s degree holders in STEM occupations are foreign born, as were just under half of all PhD holders. Moreover, his calculations show that immigrants account for two-thirds of the growth in the number of all employees in STEM occupations since 1995.6

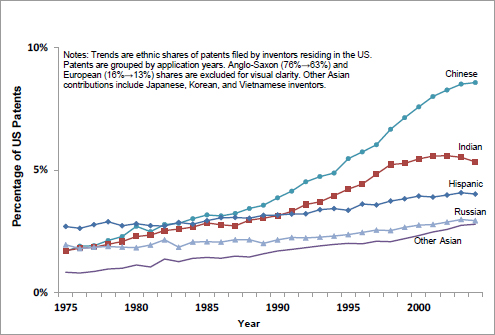

One measure of the role of immigrants in U.S. innovation is the percentage of patents granted using ethnic-name techniques, an educated guess about an inventor’s nationality based on the ethnicity of that person’s last name.7,8 In

_________________________

6Kerr, William. 2007. “The Ethnic Composition of U.S. Inventors,” HBS Working Paper 08-006.

7Ibid.

8Kerr, William and W. Lincoln. 2010. The supply side of innovation: H-1B visa reforms and U.S. ethnic invention, Journal of Labor Economics 28(3):473-508.

1975, 80 percent of patent holders living in the United States had Anglo Saxon last names, with individuals with Chinese, Indian, Hispanic, Russian, and other Asian surnames each accounting for fewer than two percent of patent holders at the time (Figure 6-4). Over the past 30 years, the share of patent holders with Anglo Saxon names fell by 10 to 13 percentage points relative to 1975, with a dramatic increase in patent holders with Chinese and Indian surnames, as well as increases in most other non-Anglo Saxon and non-European categories. These trends are also found in the patent application data.

These data do not provide a direct snapshot of immigration’s impact on innovation because it is impossible to say if someone with an ethnic surname is a first generation or fourth generation American. However, census data show that the share of individuals with ethnic surnames that are first generation immigrants is large. In addition, using data from a variety of sources, including surveys of Silicon Valley firms, fast-growing companies, and recent initial public offerings, Kerr estimates that immigrants have accounted for about 25 percent of the innovation activity in the U.S. economy.

Kerr also discussed the contradictory evidence about productivity of immigrants. On the one hand, he noted Paula Stephan’s work showing that immigrants make up a disproportionate share of U.S. highly cited authors, members of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, and holders of top-ranked patents. He also noted Lindsay Lowell’s earlier comment that while the number of immigrants who have won these awards has declined, immigrants still represent a disproportionate share of these high-impact measures. According to Jennifer Hunt’s work, education level and field of study explain why immigrants perform better than the typical native in terms of patenting, entrepreneurship, and other outcome variables. Kerr also acknowledged that immigrants are more likely to patent, publish scientific papers, and start new companies. After controlling for differences in education level and the field of study, however, most of the differences between immigrants and natives go away, although immigrants are more likely than native-born inventors to hold patents. Any difference in patenting or innovative activity between the immigrant and native-born population may be due to differences in quality or the number of students attracted to PhD programs. The quality of immigrants may be higher than natives enrolling in PhD programs, and there are some “superstar” researchers who attract clusters of immigrant students. Kerr also noted immigrants and natives who obtain a master’s degree in electrical engineering appear to have similar abilities as far as producing innovations, so the immigrants’ observed advantage comes from their being more likely to pursue that degree in the first place.9

_________________________

9Hunt, J. 2011. Which Immigrants are most innovative and entrepreneurial? Distinctions by entry visa, Journal of Labor Economics, 29(3):417-457.

FIGURE 6-4 The percentage of U.S. patents granted to U.S. residents with ethnic surnames. SOURCE: Kerr and Lincoln, 2010.

Superstars aside, what will be the impact of high-skilled immigrants on native U.S. workers? According to Kerr, if the quality of the individuals is the same and if they make the same investments in education, the overall impact will depend on quantity and whether the number of immigrants entering a particular STEM field crowd out natives. An increase in the number of immigrants entering a given field may cause the labor supply curve to shift out and lead to lower salaries. However, if innovation and productivity increases, the result may not hold. Studies have shown that cities that have more H-1B visa holders experience increases in productivity above the national average and natives are not crowded out of occupations held by H-1B visa holders.

On the other hand, studies of specific occupations have more varied results. One study looking at the impact of the large number of Russian mathematicians who came to the United States in the 1990s found that there was a negative impact on the number of natives employed in mathematics jobs.10 Some studies have shown that native students specialize in other educational areas if

_________________________

10Borjas, G., and K. Doran. 2012. The collapse of the Soviet Union and the productivity of American mathematicians, Quarterly Journal of Economics 127(3):1143-1203.

immigrants are competing for jobs.11,12 However, a study of immigrant chemical engineers who fled Nazi Germany found many positive effects related to the growth of the chemical industry that occurred along with that large influx.13 Kerr also noted that he has failed to find any evidence that there is a “crowding in” effect with respect to the majors that students choose, that is, having a large number of foreign students enrolling in specific majors is not triggering an influx of native students into those majors.

There are several important research questions that focus on the impact of immigrants on U.S. native workers. One question is how well local labor markets model the decisions that firms make with regard to high-skilled migrants given that individuals can move within a country as well as between countries. Is Microsoft’s labor market Seattle, the entire United States, or the world? Another question concerns the role of growth and whether there are opportunities for growth that can enable companies to hire immigrants and then build complementary resources around them. In the case of the wave of Russian mathematicians, many of them were hired by universities that were constrained in terms of further growth, which had the result of limiting opportunities for native-born mathematicians.

While much of the discussion around immigration policies looks at the issues at a national or regional level, choices regarding who gets an H-1B visa are made by individual firms, and the visas are granted on a first-come, first-served basis with a regulated cap. As a result, debates about immigration policy in the United States need to be informed by how companies are using this program and how they view immigrants in the context of all of the hires they need to make. Global firms can hire some of their workers outside of the United States without using one of the limited numbers of H-1B visas.

The economics of firms can dramatically shape the structure of U.S. immigration. Kerr noted that the H-1B program’s composition is dependent on firm demand. There are large fluctuations in H-1B visas going to workers from India and to computer-related workers in general since 1995. These fluctua-

_________________________

11Lowell, B. L., and H. Salzman. 2007. Into the Eye of the Storm: Assessing the Evidence on Science and Engineering Education, Quality, and Workforce Demand. Urban Institute Working Paper. Available at http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED498867.pdf [Accessed October 28, 2014].

12Orrenius, P., and M. Zavodny. 2013. Does immigrations affect whether U.S. natives major in science and engineering? Journal of Labor Economics, 33(S1):S79-S108. Available at www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/676660?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents [Accessed December 16, 2015].

13Moser, P., A. Voena, and F. Waldinger. 2014. German-Jewish Emigres and U.S. Invention. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 19962. Available at www.nber.org/papers/w19962.pdf [Accessed December 17, 2015].

tions follow the booms and busts in the information technology sector and reflect demands at the corporate level. Temporal shifts in firm and industry demands affect as much as 30 percent of the visa allocation in terms of country of origin and occupation. A system that allocates visas on a first-come, first-served basis without restrictions regarding the composition of visas to be distributed will always possess this characteristic.

A high-skilled immigration policy needs to be developed within the larger dynamics of the firm and take into consideration how these firms fill their occupational needs. Kerr’s recent work has found that firms that are hiring high-skilled migrants are simultaneously expanding and creating opportunities for complementary workers.

William Lincoln started the discussion by complimenting Paserman on the approach he had taken to examine the correlation between high-skilled immigration and productivity at either the firm or industry level. He suggested that Paserman dig deeper to gain a better understanding as to why there was not much of an effect on productivity at the micro level. It may be possible to look at firm creation or economic output, depending on data availability. Another potential avenue of research on the effects of immigration at the firm level might be to look at reallocation effects, that is, the effects of changes in market shares across firms resulting from immigration. Overall, the effects of immigration at the firm level have not been widely studied yet.

Lincoln then commended Brücker for his work looking at the role that institutions play in immigration. Of particular interest were Brücker’s findings that higher wage flexibility increases the benefits from immigration, and the overall benefits of high-skilled immigration increase with how well immigrants assimilate and can compete with natives of similar backgrounds. These findings are important to maximize the effectiveness of immigration policy, perhaps by encouraging assimilation of immigrants. Brücker might consider looking at the effects of assimilation by country of origin given that assimilation is likely to be different across different countries of origin. Brücker should also consider building potential productivity effects from immigration into his models.

Kerr’s presentation pointed out that institutional differences can significantly affect immigration’s impact on labor markets. In settings where there are constraints to growth, as is arguably the case in academia, immigration might lead to more displacement rather than additional innovation or growth. A needed area of research is to look more closely at the factors in the institutional environment correlated with higher growth and to determine the factors

encouraging displacement of native workers. For example, why did universities hire fewer native mathematicians following an influx of Russian mathematicians rather than hire fewer English literature scholars?

Panel moderator Ellen Dulberger started the discussion by asking the panelists if the degree to which a country participates openly in global trade has an impact on the elasticity of wages and its ability to attract immigrants. Lincoln responded that research has shown that more immigration leads to a greater amount of trade and vice versa, and that trade and immigration policies could be more closely intertwined. He added that the link between trade and innovation is something that researchers are exploring now.

Brücker said that a country’s openness to global trade certainly has an impact on immigration, and he added that traditional models that treat local labor markets as small economies that do not trade are “certainly wrong.” He also noted that research shows that a higher level of product-market competition in international markets contributes to an increase in wage elasticity. “It may also spread effects on wages and on labor markets in a way that is relatively similar to the impacts we have at the aggregate level if the capital stock adjusts,” said Brücker. “If the capital stock adjusts, a large part of these effects at the aggregate level disappears, and the same is true for trade.” What he and his colleagues have observed in Germany, and which he believes holds true for many other countries with a strong export position, is that being an exporter attracts migrants through what might be thought of as an advertising effect. For example, exporting automobiles is a good promotional campaign to attract migrants to the exporting country.

Paserman said that one area that needs more in-depth study is the role that large multinational firms using immigration to staff their various locations play in immigration patterns. He and a colleague have been looking at the foreign-directed investment decisions that U.S. multinational corporations are making in relationship to their U.S. STEM workforce. What they have found is very tight connections between the countries from which they draw migrant STEM workers to the United States and the direct investments in research and development that they make in those countries.

A member of the audience from the OECD asked if there was some way to factor nonlinearity into studies looking at the connection between immigration and innovation so that these studies could provide answers to policy makers that go beyond, “Yes, immigration is good. Let as many people in as possible,” and “No, immigration is bad and it should go to zero.” Paserman said that Brücker’s structural models are headed in that direction because they provide the ability to extrapolate from current data to ask what will happen to innova-

tion as the level of immigration is increased or decreased. Brücker added that his model will only be good for looking at marginal effects of changing immigration numbers, not big shocks. Lincoln said that he believes that most of the work being done today examines various pieces of the immigration and innovation picture, but when taken as a whole they can provide a broader picture of what the costs and benefits will be.

Neil Ruiz, from the Brookings Institution, asked Lincoln how immigrant mobility is tied to innovation and whether there is more demand for temporary client-based work that serves an overarching factor in total demand. Lincoln replied that his research has found that innovation in the United States tends to cluster regionally around where an initial innovation occurs. As an example, he said that if the world’s best mousetrap had been invented in a particular city, much of the subsequent innovation in mousetrap design will be in that same city. Immigrants are an important factor in driving that clustering phenomenon. In terms of immigrant mobility, Lincoln said that what he has found is that immigrants are flexible about where they first settle in the United States, but they are subsequently no more mobile than natives.

Philip Webre, from the Congressional Budget Office, asked if companies can bank H-1B applications, that is, can they apply for an H-1B visa without having identified a specific individual to hire. Jennifer Hunt responded that an H-1B visa application is person-specific, and Kerr added that in some cases, multiple firms may apply for an H-1B visa for the same individual. Webre also asked Kerr if he had any insights about why some companies eventually sponsor their H-1B visa holders for permanent residence status and others do not. Kerr replied that he did not.

An audience member asked whether any research has been conducted looking at the connection between gross expenditures on research and development as a percentage of gross domestic product and immigration, or between the existence of intellectual property rights and immigration. Lincoln replied that these would be fruitful areas of research.

Another audience member then asked Paserman if he could comment on how Israel handled the huge influx of Soviet immigrants and if Israel is seen as a natural destination for displaced people trying to find a safe haven in the world. Paserman said that the reaction of Israelis to the influx of Russian immigrants was to see it as almost a miracle that so many Jews would be free to leave the Soviet Union and come to Israel. On a more personal level, there were conflicts in areas where there was competition for jobs or where Israeli professionals felt that there Russian colleagues were not as competent or well-trained as their degrees or experience would indicate. In terms of Israel being seen as a safe haven for refugees, Paserman said that the large influx of migrants from Africa, particularly from Sudan and other war-affected countries, has not been as well-received by Israelis. Reaction has been more along the

lines of how Americans view illegal immigrants from Mexico or how Europeans react to workers from North Africa. He added that it is not a matter of Israeli policy to admit refugees from Syria or Iraq.

Dulberger noted that the workshop presented a great deal of evidence about the mixed impacts of high-skilled immigration. She also noted that the data show that there has been limited success in various countries’ abilities to absorb high skilled immigrants into the professions of their first choice and in which they have been trained. That observation, she said, suggests that there may be an opportunity, especially with widening availability of information and data from around the world, to do a better job of matching immigrants’ skills with job opportunities.

This page intentionally left blank.