3

Systems Strategies for Continuous Improvement

The health care system is a complex collection of interacting elements, each of which affects the others in myriad ways. Effectively dealing with any health care system issue—especially as basic as scheduling and access—requires dealing with the various system dynamics in a coordinated way that takes into account how changes in one area will affect the functions in other areas. That is, it requires systems strategies and approaches.

Over the past 15 years, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) and the National Academy of Engineering (NAE), working both independently and collaboratively, have released publications calling attention to the growing concerns of patient safety, the quality of care delivered, and the cost of health care and also identifying potential solutions based on systems engineering approaches that have been widely adopted in technology and service industries (IOM, 2000, 2001a; IOM/NAE, 2005; Kaplan et al., 2013). For instance, the 2005 report Building a Better Delivery System, jointly published by the IOM and the NAE, observed that moving toward a functional system requires each participating element to recognize the interdependence of influences with all other units (IOM/NAE, 2005). More recently, a discussion paper described that a systems approach to health is “one that applies scientific insights to understand the elements that influence health outcomes, models the relationships between those elements, and alters design, processes, or policies based on the resultant knowledge in order to produce better health at lower cost” (Kaplan et al., 2013, p. 4).

Many other industries have faced issues similar to the scheduling and access issues faced today by the health care industry and have dealt successfully with them using systems strategies. In this chapter, the commit-

tee looks in particular to various industrial sectors for lessons on systems strategies that can be applied to health care. The chapter reviews the theory and practice of systems strategies as they have been applied to achieve continuous improvement in industry and how those strategies might be applied in health care, especially to improve scheduling and access.

LESSONS FROM INDUSTRIAL ENGINEERING PRACTICES

The tools of operations management, industrial engineering, and system approaches have been shown to be successful in increasing process gains and efficiencies (Brandenburg et al., 2015). In particular, a wide range of industries have employed systems-based engineering approaches to address scheduling issues, among other logistical challenges.

Systems-based engineering approaches have also been employed successfully by a number of health care organizations to improve quality, efficiency, safety, and customer experience, and these approaches have great potential for enabling further improvements in health care delivery (IOM/NAE, 2005). The success of these approaches will be dependent on achieving an overall integration across various health care domains and an application across interrelated systems rather than piecemeal testing across individual processes, departments, or service lines. By approaching improvement as a whole-system effort, a number of industries coordinate operations across multiple sites, coordinate the management of supplies, design usable and useful technologies, and provide consistent and reliable processes. With the right approach, it is likely that these principles can be applied to health care (Agwunobi and London, 2009).

Box 3-1 provides examples of systems strategies that originated in industry. The following sections further describe certain systems strategies that have been more widely applied to improve health care operations and performance. They are intended to illustrate the potential of systems approaches to improve health care scheduling and access.

Lean and Six Sigma

Lean is a value-creation and waste-reduction philosophy that was initially developed within the context of an automobile manufacturing system—the Toyota Production System—but that has now spread widely to service industries throughout the world. According to Lean philosophy, value is defined from the customer’s orientation, meaning that valuable products and services are those that contribute to a customer’s experience and needs and that can be provided to the customer at the right time and for the right price, all as defined by the customer (Womack et al., 2005). Correspondingly, waste is anything that does not add customer-defined

BOX 3-1

Systems Strategies

Deming Wheel or Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) is a systematic series of steps for continuous improvement of a product or process. The cycle involves a “Plan” step, which involves identifying a goal and putting a plan into action; a “Do” step, in which the plan is implemented; the “Study” step, in which outcomes are monitored for areas for improvement; and the “Act” step which can be used to adjust the goal, to change methods, or to reformulate the theory.

Flow management is an operations research methodology involving the study of work flow and the introduction of dynamic control into processes.

Human factors engineering works to ensure the safety, effectiveness, and ease of use of various technological designs by explicitly taking into account human strengths and limitations in interactions with complex systems.

Lean is an integrated socio-technical systems approach and is derived from the Toyota Production System. The main objectives are to remove process burden, inconsistencies, and waste. In health care, the application of Lean has focused on the reduction of non-value-added activities and involves the identification of system features that create value and those that do not.

Queuing theory applies the mathematical study of waiting lines or queues in order to better design systems to predict or minimize queues. A variety of nonlinear optimization techniques (some based on the principles of statistical process control) have been put to work on different queuing applications, including challenges in telecommunications (phone call traffic), banking service management, vehicle routing, and even the express delivery of mail. Queuing theory has begun to be applied to multiple processes in health care involving groups or queues of patients.

Six Sigma is a quality management and continuous process improvement strategy. It improves efficiency by reducing variations in order to allow more capable and consistent products or processes. Six Sigma relies on the ability to obtain process and outcome data adhering to five principles: define, measure, analyze, improve, and control.

Statistical process control is a method of quality control that uses statistical methods to monitor and control a process to ensure that it operates at its full potential. This model focuses on the analysis of variation, the early detection of problems, and the reduction of waste and repeat work. In non-manufacturing applications, it has been used to identify bottlenecks in a system and reduce delays, including wait times.

Theory of constraints is a management paradigm used in complex systems to identify the most important limiting factors (constraints) in order to improve the performance of the system. Its application to health care is slowly increasing, and it has been used to increase capacity and revenue.

value to a product or service. The Lean approach relies on the continuous improvement of workflows, handoffs, and processes that function properly (Holweg, 2007; Ward and Sobek II, 2014). These workflows, handoffs, and processes required to produce and deliver a product to the customer constitute a “value stream.” Value stream mapping is an important tool of the Lean approach. It documents in great detail every step of each process in a flow diagram, and it provides a visual portrayal of the many intricate details, sequences of workflow, and interdependencies in a process, which makes it possible to more easily identify problems and inefficiencies. As such, value stream mapping facilitates identifying activities that contribute value or waste or that are in need of improvement.

Lean is well suited for making changes to groups of processes rather than for making small, discrete changes to a single process, and in health care it has typically been used in large settings like hospitals. Lean has been used to improve both operational processes and clinical care, with applications ranging from improving insurance claims processing and improving patient safety processes to establishing a standardized set of instruments for surgical procedures (Varkey et al., 2007; Womack et al., 2005). The Lean philosophy has also been applied to health care delivery to reduce wasteful activities such as delays, errors, and the provision of unnecessary, inappropriate, or redundant procedures or care (Young et al., 2004). This capability is particularly promising for improving scheduling and access in health care.

Another business management and continuous process improvement strategy that has been widely adopted across service industries is Six Sigma.1 Originally developed in Motorola, the approach is rooted in statistical process control and is aimed at dramatically reducing errors and variation. The term Six Sigma refers to achieving a level of quality so that there are no more than 3.4 defects per million parts produced. The Six Sigma approach has five phases, identified as define, measure, analyze, improve, and control (Harry, 1998). After its development at Motorola, the method was quickly adopted by industries ranging from hospitality to finance. Like Lean, Six Sigma has been applied to improve health care operations and delivery, with applications ranging from insurance claims processing to reducing medication errors and improving patient flow through laboratory services (Kwak

______________

1 Six Sigma is a data-oriented practice that originated in the manufacturing sector with interests to dramatically reduce defects from a production process. The approach has been applied both from a technical sense and a conceptual sense across various fields of practice. Sigma in statistics denotes deviation from the standard. At a one sigma level, the process may produce 691,462 defects per million opportunities (DPMO), and at three sigma, approximately 66,807 DPMO. At a six sigma, the process produces only 3.4 DPMO with a total yield of 99.99966 percent. Beyond the technical approach, Six Sigma concepts have also been used as a generic root cause analysis to detect and rectify defects toward reaching strategic goals (Evans and Lindsay, 2015; Schroeder et al., 2008).

and Anbari, 2006). Lean and Six Sigma are often combined when a key goal is to reduce waste and errors (Gayed et al., 2013; Paccagnella et al., 2012).

Crew Resource Management

In response to a series of airplane crashes caused by human error, the airline industry developed Crew Resource Management (CRM), a system for job training and information sharing (Cooper et al., 1980). Since CRM has been adopted industry-wide, pilots, flight attendants, and ground crews proactively communicate and work cooperatively, using tools such as checklists and dedicated listening techniques that have greatly reduced the hazards of commercial air travel. In the United States, the rate of fatal commercial aviation accidents fell from approximately seven per million departures in the mid-1970s to around two per million departures in the mid-1980s (Savage, 2013). Since 2005, the rate of fatal aviation accidents has remained under one per million departures (Savage, 2013).

The value of using checklists is already beginning to be realized in health care (Pronovost et al., 2006). Most notably, the checklists used in preoperative team briefings to improve communication among surgical team members are indicative of the potential that checklists have to improve patient safety (e.g., reduce complications from surgery) and reduce mortality in general (Borchard et al., 2012; Haynes et al., 2009; Lingard et al., 2008; Neily et al., 2010; Weiser et al., 2010).

Customer Segmentation and Cluster Analysis

Service and e-commerce industries commonly use customer segmentation and cluster analysis—modeling and marketing techniques that group potential customers by characteristics and preferences in order to appropriately tailor products and services. For example, Amazon looks to previous purchases and browsing behaviors to profile and segment its customer base (Chen, 2001). Netflix uses data mining and machine learning techniques to cluster user behavior data, like product ratings and page views, as well as product features such as movie genres and cast members to recommend new movies that customers are likely to rate highly (Bell and Koren, 2007). Values, Attitudes, and Lifestyles (VALS) is a commonly used research methodology for customer segmentation. Developed in 1978 by social scientist Arnold Mitchell at Stanford University, VALS breaks down customer motivations and resources and remains an integral aspect of large company marketing strategies to this day (Yankelovich and Meer, 2006).

One setting in which patient segmentation has been applied in health care is the use of patient streams in emergency departments. Patient streaming is the use of set care processes (or streams) to which patients are assigned

upon triage; a subset of streaming is fast track, in which lower acuity patients are assigned to a fast track stream (Oredsson et al., 2011). Evidence on patient streaming is limited, although studies suggest that use of severity-based fast track in emergency departments can be effective at reducing waiting times, length of stay, and the number of emergency department patients who leave before being seen, while also increasing patient satisfaction (Oredsson et al., 2011). These limited uses of patient segmentation therefore focus on patient characteristics like severity, urgency, and likelihood of adherence, but less information is known about the potential of segmentation by patient-driven characteristics, such as preferences and values (Liu and Chen, 2009).

Deming Wheel or Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) Cycle

Deming Wheel or Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle is the scientific method used for action-oriented learning (Taylor et al., 2013). The PDSA cycle is a series of steps for gaining insight of the control and continuous improvement of a product or process. The cycle involves a “Plan” step, which involves identifying a goal and putting a plan into action; a “Do” step, in which the plan is implemented; the “Study” step, in which outcomes are monitored for areas for improvement; and the “Act” step, which can be used to adjust the goal, to change methods, or to reformulate the theory (Taylor et al., 2013). The PDSA steps are repeated as part of a cycle of continuous improvement. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) Model for Improvement focuses on setting aims and teambuilding to achieve change. The model uses a PDSA cycle to test a proposed change in the actual work setting so that changes are rapidly deployed and disseminated, and it is best suited for a continuous process improvement initiative that requires a gradual, incremental, and sustained approach to process improvement changes that are not undermined by excessive detail or unknowns (Huges, 2008).

Common to each of these practice areas is the integrative dimension. A systems approach emphasizes integration of all the systems and subsystems involved in a particular outcome. Adjusting each component of a system separately does not lead to an overall improved system. The fundamental elements of a systems approach to health care scheduling and access and the potential of systems strategies to improve scheduling and access are discussed in the next section.

SYSTEMS STRATEGIES FOR HEALTH CARE SCHEDULING AND ACCESS

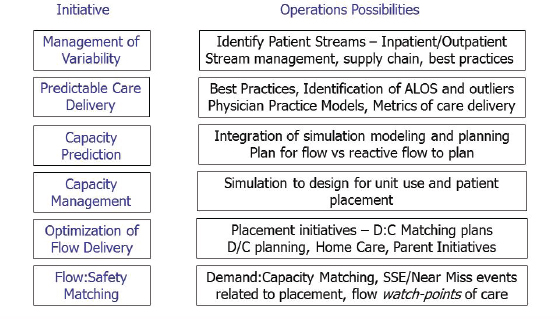

The committee’s view is that by using systems strategies, the organizational capacity or performance of health care system can be dramatically improved. Essential to the process is an understanding of the many system complexities and interdependencies. Although different resources and talents may require near-term additions, the aim is for better performance with fewer resources per service provided. Additional personnel and financial investment are generally not essential to achieving significant improvements in capacity over time (Lee et al., 2015b; Litvak, 2015). Figure 3-1 depicts the key principles of capacity management and their operational applications at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC), which was able to significantly improve productivity. CCHMC includes an administrative group that oversees the capacity of the system and evaluates and designs strategies to match changing demand. Using techniques of production planning from industry, CCHMC combines management and staff to set operating rules, monitor supply, measure delays, and make decisions about how shared resources are deployed.

FIGURE 3-1 System capacity management roadmap.

NOTE: ALOS = average length of stay; D:C = demand to capacity; D/C = discharge; SSE = serious safety event.

SOURCE: Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Defining Focus, Identifying the Components, and Building the Capacity

The basic building blocks of applying a systems approach to health care scheduling include fixing the system orientation on the needs and perspectives of the patient and family; understanding the supply and demand elements; creating capacity for data analysis and measurement strategies; incorporating evolving technologies; creating a culture of service excellence; assuring accountability and transparency; committing to continuous process improvement; and developing a supportive culture and organizational leadership that empowers those on the front lines to experiment, identify the limitations, and learn from those trials. These elements of health care scheduling from a systems perspective are discussed in more detail in the remainder of the chapter. With additional research and testing, these elements of health care scheduling could potentially serve as general principles for improving primary, secondary, hospital, and post-acute care. Although these elements are discussed independently, the central premise lies in their interplay; health care organizations are not discretely separated environments or services, but they are complex groups of processes, personnel, and incentives. These core access principles are therefore interdependent.

Fixing the System Orientation on the Patient and Family

Systems approaches focus on improving products and services placing customer needs at the forefront. When translating these approaches from the commercial setting to health care, however, identifying the “customer” has been challenging, because customers of health care may include patients and their families, providers (e.g., physicians), hospitals, and payers (e.g., the government, insurers, taxpayers) (Womack et al., 2005; Young et al., 2004). For example, improving scheduling includes reducing wasted time for both providers and patients. However, as described in Chapter 1, the committee’s “How can we help you today?” philosophy for health care scheduling and access is driven by meeting patient need. Fundamentally, the patient is the primary focus for the organization and delivery of health care services and products. The activities to improve health care scheduling and access should aim to improve the patient experience and meet patients’ needs as the foundational tenet of a patient-centered health care system (Bergeson and Dean, 2006).

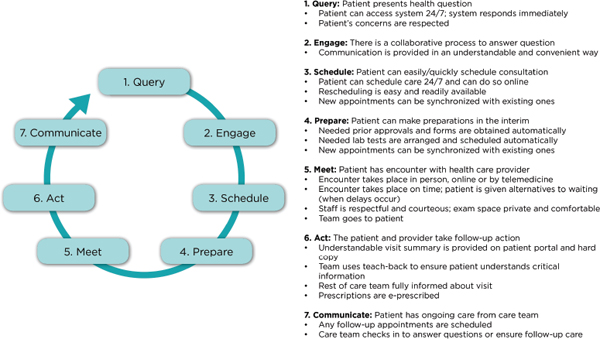

The committee developed a framework for patient and family engagement for care, scheduling, delivery, and follow-up (see Figure 3-2). The framework uses a value-stream map for an office visit documenting the patient’s care through the visit from the perspective of the patient as well as the attributes of an ideal system. As shown in Figure 3-2, each step encountered by the patient during a visit is documented, including the many

FIGURE 3-2 Framework for patient and family engagement: Care scheduling, delivery, and follow-up.

individual steps that are not intentional yet are part of the typical process. This is followed by a determination of whether each step actually improves the patient visit in some way. Following such an analysis, steps that are not valuable to patients are eliminated.

Institutions that have involved patients in systems redesign activities have reported positive results from such efforts, including improvements in patient safety with reductions in medical errors and improved satisfaction among patients and health care providers (Davis et al., 2007; Graban, 2012; Longtin et al., 2010; Toussaint and Berry, 2013). It is important to note that while involving patients in systematic improvement efforts has shown to have positive impacts, many unresolved questions remain that deserve additional study beyond the scope of this report, about who should be involved and how to ensure that patient involvement has more than a token impact (Armstrong et al., 2013; Martin and Finn, 2011).

Balancing Supply and Demand

Balancing supply and demand at each step along the care continuum is essential for an efficient and effective health care system (Hall, 2012). Poorly performing systems often contain design flaws, due to an excessive focus on the supply side and not on the demand side (Grumbach, 2009). Inherent capacity, for example, the number of appointment slots available, refers to the amount of demand each system can tolerate without creating a mismatch (Anupindi et al., 2005). Imbalance of patient demand and provider supply creates delays and increases wait times. If demand equals capacity, no delay exists. However, variations in either supply or demand can cause temporary mismatches that may increase wait times. Systems strategies require ongoing assessment of supply, demand, work flow, and patient flow, adjusting capacity across days and services, and continuous improvement.

In ambulatory primary care settings, temporary supply deficiencies can often be overcome by flexing or adjusting supply to keep up with demand, by temporarily increasing office hours, or adding another provider. In the primary care setting, capacity is determined by the number of providers, their hours worked, and the total number of patients seen each day. Capacity in the primary care setting is maximized through balanced panel sizes, a commitment to continuity, an appointment decision logic that directs patients to their own provider rather than the first open slot, and fully developed contingency plans that can address demand or supply variations. Optimal performance in this setting is currently measured as a TNA of zero for each patient’s regular primary care provider (Murray and Berwick, 2003).

In the specialty care setting, capacity is affected by competing demands, with provider presence having the greatest impact. Capacity, therefore, is

influenced by the frequency of which specialists are absent from the office. A key factor in this setting is that new patients can be a more critical part of a specialty care practice, which necessitates the creation of specific provisions for accommodating both the high volume of work associated with a new patient and the large number of returning appointments that must also be available. As a result, capability in specialty care settings is often determined by the volume of new patients. Whereas primary care systems are designed for providers to act and function as independent units, specialty care systems are designed to function as units of interchangeable providers. In that respect, the design elements that can enhance the capability of specialty care practices include a logic that offers appointment to the first available new patient slot for any provider among the entire set of interchangeable providers, a commitment to continuity once a new visit is completed, and fully developed contingency plans to address demand or supply variation.

Creating the Infrastructure for Data Analysis and Measurement

A health information technology infrastructure, including the creation and implementation of electronic health records (EHRs), is designed to generate data that will enhance the quality of patient care. Better use of the capacity to track patient flow through the health care system is a logical application, with potential to improve understanding of patterns of patient demand, provider supply, and bottlenecks to patient flow, and, as a result, improved revenues, hospital performance, and patient care (Devaraj et al., 2013). Indeed, implementing and sustaining systems strategies to improve scheduling in health care requires real-time performance data. However, most data systems do not currently include operational (e.g., wait times) data.

New systems should ensure that operational data integrate seamlessly with existing processes, and also that operational data are interoperable to enable communication and data exchange with other health care organizations to allow for the creation of a nationwide health information network. To facilitate operational data interoperability and the assessment of comparative performance across various care settings, practices, and circumstances, data need to be collected in a standardized, consistent, and sustained manner. Several aspects of health care scheduling and access that should be measured and for which standards should be identified include: patient and family experience and satisfaction; care match with patient goals; scheduling practices, patterns, and wait times; cycle times, provision and performance experience for alternative care models (e.g., telehealth and other remote site services); and effective care continuity.

The most important standards-setting organization is the individual health care organization itself. Therefore, each health care organization will need to define measures to assess its commitment to creating a standard of

care and performance culture that supports timely scheduling and access. However, to define these measures and identify appropriate standards for scheduling and wait times, for which there are no existing national standards or benchmarks, health care organizations will need reliable information, tools, and assistance from various national organizations with the requisite expertise in developing and testing standards. Furthermore, given the need for flexibility of measures to assess the goals and performance of individual organizations, developing a measurement infrastructure for operational data will require inter-organization coordination to ensure harmony of reporting instruments and reference resources across the nation.

Once standards and benchmarks for access and wait times and corresponding patient experience measures have been identified, such performance data should be accompanied by analytic tools that can continuously monitor current conditions, including the scheduling measures of supply and demand. Health care organizations, again with the assistance of national organizations with expertise in developing and testing standards, will also need to develop, test, and implement standardized approaches to analyzing operational data.

Incorporating Evolving Technologies in Health Care

Various technologies are emerging with strong potential to improve real-time access to care, with the promise of totally new ways of scheduling and delivering care and gathering information on its utility. Use of digital and social media, telemedicine and telehealth, remote monitoring, and related evolving technologies are also well suited for deployment in health care practices. Still, their uptake has been relatively limited to date, for such reasons as unfamiliarity, system mismatch, and absence of reimbursement. Quickening use of these tools in health and health care will require receptivity to innovation, novel partnerships, and collaborative information and experience gathering. Health care providers are slowly developing new skills and integrating novel uses of technology into their organizations. The Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act has accelerated use of EHRs, including more use of patient portals to aid information exchange with hospitals and other providers within the same system (Adler-Milstein et al., 2011).

Expanding EHR capabilities foster substantially enhanced insights into the continuum of patient and family experience, documentation of different patient information and preferences, analysis of data trends and predictions, and the integration of real-time monitoring of operations. To effectively use technology requires trust in the tools, adequate education of its potential, and a greater service commitment from the technology sector both for those working within the health care arena and for the patients.

The benefit to both parties must be demonstrated and reinforced, in part through organizational leadership and through individual providers. As practice efficiency and reimbursement changes occur, additional payment reform may be needed (Howley et al., 2015).

Some patients are beginning to take control of their own scheduling as they are gaining access to their medical information. This is not an entirely novel practice, having been implemented in high-performing, early-adopting organizations and practices. The changes described above point to a time when all clinical information is instantly available throughout the nation; when the EHR reveals not only past and scheduled appointments but also the sequence of referrals to specialists and resulting input, and patient preferences are documented throughout the scheduling process.

Creating a Culture of Service Excellence and Leadership Stewarding Change

Implementing systems approaches in health care, including strategies to address scheduling and access issues, requires changes not only in operational processes but also a fundamental shift in thinking. All members of a health care organization must transition from the siloed, independent, and fragmented mentality of traditional health care culture to a culture of service excellence, an integrated approach with shared accountability in which physicians, employees, and patients treat one another with respect and as partners, and patient satisfaction and employee engagement are high.

Organizational and cultural changes needed to support the implementation of systems approaches will require new competencies and participation from all members of a health care organization’s senior management team (Trastek et al., 2014). Moreover, because changing an organization’s culture often happens slowly, leadership and governing bodies at each level of the health care delivery sites are important in order to drive culture change and manage ongoing process changes (Kabcenell and Luther, 2012). Leadership is also important to establish and model standards of behavior for all employees and to establish educational opportunities to help employees learn the new behaviors. Finally, leadership and governing bodies’ commitment at each level of the health care delivery sites is essential to promote transparency, accountability, successful adoption of technology, and continuous process improvement through ongoing monitoring of performance and process to avoid backsliding.

Transparency and Accountability

Transparency on performance draws data from disparate sources and delivers them to those at the front lines of care, including both patients

and providers. Transparency helps employees understand the relevance and impact of change, informs and motivates their actions (on access, scheduling, or the other important elements of the care process), and helps organizations track the progress that they are making toward the desired new culture. Applied to scheduling and access, transparency about operational processes and their effectiveness can facilitate identification of delays and their causes, and also the progress made to reduce those delays. Finally, transparency facilitates messaging that creates organizational consistency—when everyone hears the same message from their leaders, they are motivated to respond in similar ways, and this behavior change can reinforce culture change.

The corollary requirement to transparency is accountability, or shared responsibility for organizational performance, to ensure that change is sustained in an organization (Blumenthal and Kilo, 1998). Accountability for all persons promotes accountability at all levels of an organization (O’Hagan and Persaud, 2009). Whereas the fragmented, independent nature of traditional culture may lead to lack of accountability or individual blame, in a culture of service excellence that takes a systems approach to improvement, accountability ensures that problems are analyzed in a holistic manner. Applied to scheduling and access, accountability may help ensure that delays in patient flow are addressed by all relevant stakeholders across the care continuum, rather than with independent, piecemeal process changes.

Continuous Process Improvement

A defining characteristic of modern health care is the rapidly accelerating increase in information that is available to assist with the delivery of care and system management. This places a high premium on the need for systems to effectively manage the flow of information, but it also requires a commitment by the organization to build and incorporate processes for continuous learning, knowledge sharing, and innovative change. Such characteristics are shared by health systems, including Denver Health, Geisinger Health System, Kaiser Permanente, Seattle Children’s Hospital, ThedaCare, and Virginia Mason Hospital and Medical Center, who have adopted methods of continuous improvement such as Lean, the IHI Model for Improvement, and Six Sigma to empower teams to question how things are done and recommend operational changes to improve efficiency (Brandenburg et al., 2015).

Continuous process improvement uses data for ongoing improvement of the quality of a product or service. Continuous process improvement encourages all health care team members to continuously question how they and their system are performing and whether performance can improve (Edwards et al., 2008). Data, transparency, and accountability are critical

enabling factors for a learning culture, which requires the creation of a structured approach to process and outcome evaluation.

Even in the face of substantial promise from the application of systems strategies to improve scheduling and access in health care, the committee is fully cognizant of the potential barriers and challenges to achieving the gains possible (see Table 3-1). Many have already been introduced in this report. They include practice and infrastructure barriers, such as those related to the challenge of obtaining reliable data (Kim et al., 2009), the capacity of existing technology (Murray et al., 2003; Pearl, 2014), the lack

TABLE 3-1 Possible Barriers to Implementing Systems Approaches in Health Care

| Practice and Infrastructure Challenges | |

| Data | Metrics for organizational performance and clinical outcomes and systems |

| Technology | Digital health records designed for data needed, patient portals, telephone consultation systems |

| Flexibility to accommodate variable information technology uptake and use by patients | |

| Staff retraining and rescheduling for telephonic and digital communication with patients | |

| Staffing needs | Need for intervention design teams |

| Availability of trained nurses, other non-physician clinicians | |

| Patient interface personnel, reframing responsibilities, training | |

| Regulatory | Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) standards (facility and process redesign standards) |

| Cultural Challenges | |

| Preconceptions | Convincing that Lean production works with patient care as well as in manufacturing |

| Leader buy-in | Belief that systems strategies are evidence-based and refocus existing resources rather than requiring new ones |

| Staff buy-in | Assurance that retraining and reclassification are not threats and that jobs will not be lost |

| Patient skills | Need to communicate and educate patients about use of new practice procedures |

| Organizational | Moving organization from siloed, independent, and fragmented to integrated, aligned consultative, with shared accountability |

of systems expertise, and the procurement and training of the necessary clinicians and staff (Coleman et al., 2006; Dhar et al., 2011; Jack et al., 2009), and the pressures of organizational and national regulations (Lee et al., 2015; Pearl, 2014). Cultural barriers include those related to preconceptions on the use of industrial systems engineering in complex patient circumstances (Kim et al., 2006), the need for leaders, staff, and patients to develop new skills, and preexisting tendencies for organizational units to prefer to work autonomously (Cima et al., 2011; IOM, 2015; Kim et al., 2006, 2009; Krier and Thompson, 2014; Lee et al., 2015; Meyer, 2011; Murray et al., 2003). In each, committed leadership is critical to identifying and addressing these issues.