1

Improving Health Care Scheduling

“How can we help you today?” Each of us would like to hear these words when seeking health care assistance for ourselves, for our families, or for others. It should not only be our wish, but our expectation. Health care that implements a “How can we help you today?” philosophy is care that is patient centered, takes full advantage of what has been learned about systems strategies for matching supply and demand, and is sustained by leadership committed to a culture of service excellence and continuous improvement. Care with this commitment is feasible and can be found in practice today.

Yet it is not common practice. In 2001, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) landmark report Crossing the Quality Chasm identified being timely as one of the six fundamental properties of high-quality health care—along with being safe, being effective, being patient-centered, being efficient, and being equitable (IOM, 2001a). Progress has been slow on many dimensions including programs to design, implement, and share innovative scheduling and wait time practices in order to advance the evidence base and create standards and accountability. The culture, technology, and financial incentives at work in health care have only recently begun to heighten awareness and attention to the issue that delays are often not the result of resource limitations but more commonly are the product of flawed approaches to the scheduling process and poor use of the full range of available resources.

Although prompted by attention to a high-profile crisis in a health center operated by the Veterans Health Administration of the Department

of Veterans Affairs (VA/VHA), and commissioned by the VA, this report focuses broadly on the experiences and opportunities throughout the nation related to the scheduling of and access to health care. As a “fast track” Academy study, the report is limited as to the detail of practice considerations. It reviews what is currently known and experienced with respect to health care access, scheduling, and wait times nationally, offers preliminary observations about emerging best practices and promising strategies (including immediate engagement), concludes that opportunities exist to implement those practices and strategies, and presents recommendations for needed approaches, policies, and leadership.

CONTEXT: VA PHOENIX HEALTH CENTER CRISIS

In 2014, in response to allegations of mismanagement and fraudulent activity pertaining to health care scheduling, the VA/VHA Office of Inspector General conducted an audit of the VA Phoenix Health Care System. The interim report from that audit confirmed that the Phoenix Health Care System had been falsely reporting its scheduling queues and wait times. The audit found that 1,700 veterans in need of a primary care appointment had been left off the mandatory electronic waiting list (EWL) that was reported to VA/VHA leadership (VA, 2014b). Of greater concern was that the VA/VHA final report, Review of Alleged Patient Deaths, Patient Wait Times, and Scheduling Practices at the Phoenix VA Health Care System, identified 40 veterans who had died while on the EWL waiting for an appointment. While the report found that there is not enough evidence to conclude that the prolonged waits were the cause of these deaths, it documented a poor quality of care in the Phoenix system (VA, 2014e). The report further determined that in an attempt to meet the needs of both veterans and the clinicians employed by the VA/VHA, certain facilities had developed overly complicated scheduling processes that resulted in a high potential of creating confusion among scheduling clerks and frontline supervisors (VA, 2014e). The report concluded that inappropriate scheduling practices are a systemic problem across the entire system nationwide (VA, 2014e) and called for an end to arbitrary scheduling standards, for more transparency and accountability, and for more attention to be paid to the “corrosive culture” that led to the manipulation of data in the system (VA, 2014e).

In response to the findings of the audit, the VA/VHA deployed the Leading Access and Scheduling Initiative (LASI), a 90-day program to develop and deploy rapid changes across its entire system. LASI, which ended in September 30, 2014, resulted in the completion of 120 tasks and 60 deliverables, including the development of new performance management plans; the addition of primary care into the Patient-Centered Com-

munity Care for non-VA care program; a focus on transparency through the monthly publication of wait time data (VA, 2015a); and a number of activities and policies focused on schedulers, which included interviews in the field, a review of schedulers’ grades to combat high turnover rates, and an educational campaign to standardize scheduling processes across the system.

In August 2014, the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act was enacted to provide funds for veterans to receive care in the private sector in the case of prolonged waits at VA/VHA facilities and also to provide funds for the hiring of a large number of health care providers and the acquisition of additional VA/VHA sites of care (VA, 2014f). The bill also required the VA/VHA to conduct an independent assessment of the hospital care and medical services furnished in its medical facilities as well as an independent assessment of access to those services.

In October 2014, the VA/VHA established the Veterans Choice Program in accordance with Section 101 of the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act. The Choice Program addresses the VA/VHA wait time goals in such a way that veterans enrolled in VA/VHA health care will be provided clinically appropriate VA/VHA care within 30 days of making a request for medical services. Veterans who cannot receive a scheduled appointment within the 30-day standard or who reside more than 40 miles from the closest VA/VHA medical facility are able to receive care from facilities outside the VA/VHA system (VA, 2014f).

CONTEXT: NATIONAL ISSUES IN ACCESS AND WAIT TIMES

The data on access and wait times in health care are limited, and there is a prominent deficiency in research, evidence-based standards, and metrics for assessing the prevalence and impact of these issues (Brandenburg et al., 2015; Leddy et al., 2003; Michael et al., 2013). However, the limited information suggests that similar scheduling challenges are found well beyond the VA/VHA and exist throughout the public and private sectors of the U.S. health care system. The available data show tremendous variability in wait times for health care appointments within and between specialties and within and between geographic areas.

Variability in Access and Wait Times

The VA/VHA data released in October 2014 indicated an average wait time of 43 days for new primary care appointments, with a range of 2 to 122 days across all VA/VHA facilities (VA, 2014c). Detailed data from a review of Massachusetts physicians revealed average wait times of 50 days for internal medicine and 39 days for family medicine appointments (MMS,

2013). A 2014 MerrittHawkins study of appointment wait times in 15 cities across the United States found significant variation per city and per specialty. For example, average wait times to see a cardiologist ranged from a high of 32 days in Washington, DC, to a low of 11 days in Atlanta (Merritt Hawkins, 2014). A Department of Defense review of the Military Health System’s military treatment facilities and privately purchased health care services found that their average wait times for specialty care (12.4 days) and for non-emergency appointments (less than 24 hours) exceeded their internal standards, but there was variation across settings as well as a lack of comparable data with vendors because of alternative access measures (DoD, 2014).

Studies have also shown that children with coverage from Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program are more likely than those with private insurance to be made to wait more than 1 month, even for serious medical problems (Bisgaier and Rhodes, 2011; Rhodes et al., 2014). Academic medical centers, which often function as safety net providers, are less likely to deny appointments to children with Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program, but those children still experience significantly longer wait times compared to privately insured children (Bisgaier et al., 2012).

Most U.S. data on access to care come from surveys of patient experience, which refers to health care processes that patients can observe and participate in (Anhang Price et al., 2014). These include objective experiences such as wait times and subjective experiences such as trust in a provider, and provider and staff behavior such as provider–patient communication and continuity of care (Anhang Price et al., 2014). “Patient experience” is distinguished from “patient satisfaction,” which provides an assessment of a particular care experience (Anhang Price et al., 2014).

The Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) surveys are the principal surveys done on patient experiences with health care access and quality in the United States. CAHPS covers hospitals, health plans, and ambulatory care, among others. Managed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) through a public–private initiative, the CAHPS program develops standardized, tested, and publicly available measurement tools of patient experiences with health care access and quality, as well as standardized and tested methods for collecting and analyzing survey data (Lake et al., 2005). In the 2013 CAHPS clinician and group survey, 63 percent of U.S. adults reported getting appointments, care, and information for primary and secondary care when they needed it (AHRQ, 2015). In addition to CAHPS, a number of private vendors provide patient satisfaction instruments, including Arbor Associates, Inc., the Jackson Group, Press Ganey Associates, Inc., and Professional Research Consultants, Inc. (Urden, 2002).

Impact of Delays in Access, Scheduling, and Wait Times

Generally, positive patient care experiences are associated with greater adherence to recommended care, better clinical care and health care quality outcomes, and less health care utilization (Anhang Price et al., 2014). A patient’s inability to obtain a timely health care appointment may result in various outcomes: the patient eventually seeing the desired health care providers, the patient obtaining health care elsewhere, the patient seeking an alternative form of care, or the patient not obtaining health care at all for the condition that led to the request for an appointment. In any of these cases, the condition may worsen, improve (with or without treatment elsewhere), or continue until treated. Thus, long wait times may be associated with poorer health outcomes and financial burden from seeking non-network care and possibly more distant health care. Long wait times may also cause frustration, inconvenience, suffering, and dissatisfaction with the health care system.

Impact on Health Care Outcomes

Extended wait times and delays for care have been shown to negatively affect morbidity, mortality, and the quality of life via a variety of health issues, including cancer (Christensen et al., 1997; Coates, 1999; Waaijera et al., 2003); heart disease (Cesena et al., 2004; Sobolev et al., 2006a,b, 2012, 2013); hip (Garbuz et al., 2006; Moja et al., 2012; Simunovic et al., 2010; Smektala et al., 2008) and knee problems (Desmeules et al., 2012; Hirvonen et al., 2007); spinal fractures (Braybrooke et al., 2007); and cataracts of the eye (Boisjoly et al., 2010; Conner-Spady et al., 2007; Hodge et al., 2007). The timely delivery of appropriate care has also been shown to reduce the mortality and morbidity associated with a variety of medical conditions, including kidney disease and mental health and addiction issues (Gallucci et al., 2005; Hoffman et al., 2011; Smart and Titus, 2011).

A study of wait times at VA facilities analyzed facility and individual-level data of veterans visiting geriatric outpatient clinics, finding that longer wait times for outpatient care led to small yet statistically significant decreases in health care use and were related to poorer health in elderly and vulnerable veteran populations (Prentice and Pizer, 2007). Mortality and other long-term and intermediate outcomes, including preventable hospitalizations and the maintenance of normal-range hemoglobin A1C levels in patients with diabetes, were worse for veterans seeking care at facilities with longer wait times compared to those treated at VA facilities with shorter wait times for appointments (Pizer and Prentice, 2011b).

Reducing wait times for mental health services is particularly critical, as evidence shows that the longer a patient has to wait for such services,

the greater the likelihood that the patient will miss the appointment (Kehle et al., 2011; Pizer and Prentice, 2011a). Patients respond best to mental health services when they first realize that they have a problem (Kenter et al., 2013). However, because primary care providers can act as the gatekeepers for mental health care, patients face an even longer delay for mental health services because of the need to first get a primary care appointment.

Impact on Patient Experience and Health Care Utilization

Patient experience has also been shown to be associated with perceptions of the quality of clinical care (Schneider et al., 2001). A study of patient experiences in England found that although all elements of patient primary care experience (including access, care continuity, provider–patient communication, overall patient satisfaction, confidence and trust in doctor, and care planning) were associated with quality of care, straightforward initial access elements (e.g., the ability to get through on the telephone and to make appointments) were most strongly related with quality of care (Llanwarne et al., 2013).

The perception of longer wait times is also negatively associated with overall patient satisfaction (Thompson et al., 1996). A study of patients treated at a large U.S. academic medical center found that not only was overall satisfaction with the health care experience negatively affected by longer wait times, so too was the perception of the information, instructions, and treatment that the patients received from their health care providers (Bleustein et al., 2014).

Extended wait times are also associated with higher rates of appointment no-shows, as feelings of dissatisfaction and inconvenience discourage patients from attending a first appointment or returning for follow-up care (Meyer, 2001). In a survey of caregivers who brought children to an emergency department, difficulty getting needed care from a primary care provider, especially long wait times, was associated with increased non-urgent emergency department use, suggesting that delays that are unaddressed in one area of health care delivery may lead to delays in other parts of the health care system (Brousseau et al., 2004).

Scope of the Report

To address the challenges associated with access and scheduling of U.S. health care services, the VA/VHA requested the IOM to assess the range of experiences nationally and to identify existing standards and best practices. The aim was to make recommendations for improving performance

throughout the nation on health care scheduling, access, and wait times, including, but not specific to, the VA/VHA (see Box 1-1).

Study Approach

As an accelerated study, the committee’s task was addressed through one in-person meeting, which included a public workshop (a brief summary of which can be found in Appendix B), numerous conference calls, and directed staff work to assemble the evidence and identify exemplary practices. Primary attention was given in this work to gathering and examining the available evidence documenting demonstrated practices for improving access, scheduling, and wait times in health care; learning from presentations by representatives of organizations deemed to have developed beneficial strategies for productive change; and identifying principles for best practices based on the experiences of those organizations.

BOX 1-1

Statement of Task

An ad hoc committee will conduct a study and prepare a report directed at exploring appropriate access standards for the triage and scheduling of health care services for ambulatory and rehabilitative care settings to best match the acuity and nature of patient conditions. The committee will:

- Review the literature assessing the issues, patterns, standards, challenges, and strategies for scheduling timely health care appointments.

- Characterize the variability in need profiles and the implications for the timing in scheduling protocols.

- Identify organizations with particular experience and expertise in demonstrating best practices for optimizing the timeliness of scheduling matched to patient need and avoiding unnecessary delays in delivery of needed health care.

- Organize a public workshop of experts from relevant sectors to inform the committee on the evidence of best practices, their experience with acuity-specific standards, and the issues to be considered in applying the standards under various circumstances.

- Issue findings, conclusions, and recommendations for development, testing, and implementation of standards and the continuous improvement of their application.

In the course of their work, the committee will consider mandates and guidance from relevant legislative processes, review VA/VHA wait time proposals from the Leading Access and Scheduling Initiative, and evaluate all evidence indicated above, along with input and comment from others in the field.

Evidence to guide decisions or actions comes in many forms—randomized controlled trials, observational studies, and expert opinion among scientists and health care professionals, as well as that among patients and their families (IOM, 2001b). Similarly, evidence is used for many purposes, including application to learn the effectiveness of an intervention under controlled circumstances, development of standards for assessing outcomes, and use in comparing the results of different approaches under different circumstances. The strongest form of evidence, well-designed systematic trials with carefully matched controls, is important when introducing a new treatment, but is often not available, or even necessarily appropriate in the assessment of health services with highly variable input elements. The fact that trial data are not available to assess approaches to scheduling and access is not in itself limiting, but the overall paucity of reliable study and experiential outcomes data from any source presents a challenge. The committee therefore relied on an extensive environmental scan. In its scan of access and scheduling in U.S. health care services, the committee looked at the VA/VHA, private and public providers, and other sectors. The scope of the committee’s review covers first appointments and follow-up appointments for primary care, scheduling and wait times for hospital care, access to rehabilitation care, referrals to specialty care, and first appointments for mental health. The committee considered wait times to get an appointment and wait times within appointments and also ways to meet patient demand for health care other than in-person appointments.

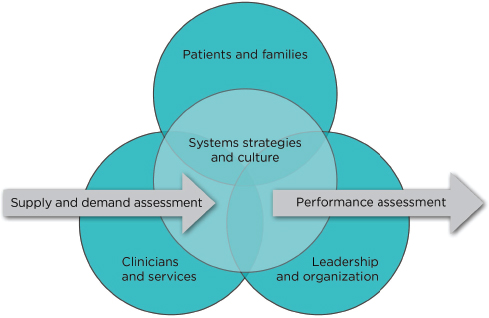

The committee also enlisted the leaders of five institutions—Denver Health, Geisinger Health System, Kaiser Permanente, Seattle Children’s Hospital, and ThedaCare—to report on the strategies, experiences, and results achieved in their respective systems (Brandenburg et al., 2015). The conceptual framework (see Figure 1-1) that was developed by the committee to guide its assessment of the factors shaping overall system performance identifies supply and demand assessments as the anchor inputs, plus major enabling or constraining influences from culture, management, patients—e.g., the leverage contributed by evidence- and theory-based systems engineering, enlightened management that creates a culture of change and improvement, and the extent of patient involvement.

According to the statement of task, the committee was to look at “ambulatory and rehabilitative care settings.” Given the evolving and adapting continuum of care, and recognizing that ambulatory, rehabilitative, and acute care are interdependent, the committee chose to focus on scheduling and access issues within acute care as well as ambulatory and rehabilitative care. Its aim was therefore to generate a report that was meaningful and relevant to the entire health care system.

The statement of task also highlighted the Leading Access and Scheduling Initiative (LASI) for consideration and analysis, and the committee

FIGURE 1-1 Framework for access and wait times transformation.

engaged in ongoing conversations with the VA/VHA about the intent and outcomes of the initiative. The information gathered during this communication is summarized above. However, in the absence of published information about LASI, the committee has not conducted additional analysis of LASI or offered findings or conclusions specific to the Initiative.

Structure of the Report

This report is intended to be useful to both the public and technical audiences and is composed of five chapters. Following this introduction and overview of the report’s goals, Chapter 2 describes the current situation concerning challenges with access, scheduling, and wait times in health care. Chapter 3 describes systems strategies for continuous improvement and offers examples of how these strategies have been applied in other sectors. Chapter 4 describes a number of emerging best practices and alternative models for scheduling, including framing and operationalizing assessments of supply and demand. Finally, Chapter 5 presents the committee’s findings and recommendations for transforming access and scheduling in health care.

A primary focus of the report is on primary care services, while laying the groundwork for improved access throughout other areas of the

health care system. Primary care services form the core of the ambulatory health care system. Related scheduling approaches are key to success of initiation around accountable care organizations (ACOs) and medical homes. A foundational element of the committee’s findings and recommendations is the centrality of orienting health care to the needs and perspectives of the patient and family (Berry et al., 2014). Patient-centered care has been described as an approach to the planning, delivery, and evaluation of health care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values (IOM, 2001a). With recent additional insights on the ability of meaningful patient engagement to improve the outcomes of care, the elements of patient-centered care have taken on additional clarity. Indeed, the committee views patient- and family-centered care not only to be designed with patient involvement to enable timely, convenient, well-coordinated engagement of a person’s needs, preferences, and values but also to include explicit and partnered determination of patient goals and care options as well as ongoing assessment of the care match with patient goals (see Box 1-2). This is the perspective that has guided the committee’s work throughout.

BOX 1-2

Patient- and Family-Centered Care

Patient- and family-centered care is designed, with patient involvement, to ensure timely, convenient, well-coordinated engagement of a person’s health and health care needs, preferences, and values; it includes explicit and partnered determination of patient goals and care options; and it requires ongoing assessment of the care match with patient goals.