6

PROMOTING SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING CAREERS IN ACADEME

Garrison Sposito

Garrison Sposito is Professor of Soil Physical Chemistry in the University of California at Berkeley. A graduate of the University of Arizona, he earned a Ph.D. in Soil Science at Berkeley and taught in both the California State University system and the University of California system before assuming his present position in 1988. He has been active in research and teaching in soil and water sciences and most recently was involved with national committees charged with setting future basic research agendas for these two disciplines of earth science.

Professor Sposito has been involved in gender-related issues through participation on the Executive Committee of the Center for the Teaching and Study of American Cultures at Berkeley. On a more personal level, he has maintained an equal participation of women and men in his research group (graduate students, postdoctoral researchers, etc.) since 1980, when he first became fully aware of some of the issues discussed in this chapter.

Women on Science and Engineering Faculties

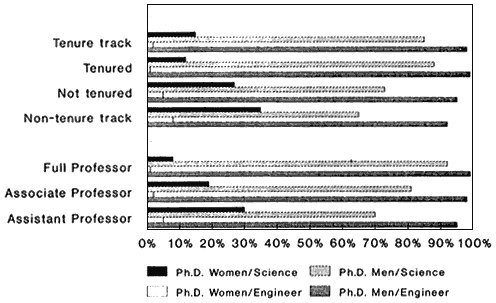

Public awareness continues to grow concerning the many contributions of women to science and engineering research, particularly those women who serve on the faculties of universities (Hoffman, 1991). Despite improving media coverage and a continual increase in the number of women who elect to pursue doctoral (or medical) degrees in science and engineering fields (CWSE, 1991; Hays, 1991), a disappointing, static picture emerges of the career patterns of women in academe. For example, about two-thirds of the women now on science or engineering faculties do not have tenure, whereas something less than 40 percent of the male faculty members now are untenured (Figure 6-1). This discrepancy is much greater in the major research universities, where both the percentage and the absolute number of women who hold the rank of professor or associate professor are very low

indeed (CWSE, 1991). Thus, although the "pipeline" into academe for women shows general increases in size and improvements in visibility, these trends have been slower and lower than would have been expected from the Ph.D. pool (CWSE, 1991; Brush, 1991).

What are the Generic Issues?

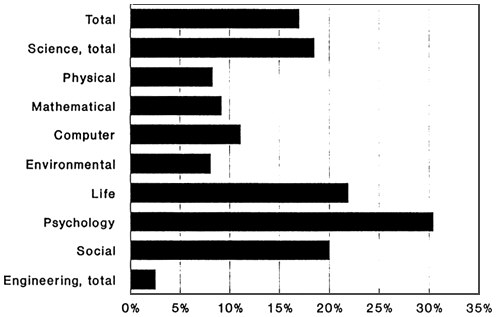

Career-related statistics for women in academe can vary greatly across scientific and engineering fields. [For example, in the University of California system, 105 of the 1,000 tenured faculty members in the life sciences are women, but there are only 47 women among the 1,000 tenured physical sciences/mathematics professors (Cota-Robles, 1991).] Some of this variability is related directly to issues that are of a particular nature: the public image of a specific field; its visibility to science and engineering majors as a career opportunity; the demand for it in the private sector; and its distribution among the academic programs of doctorate-granting universities. These issues are perhaps of lesser importance than the broad, generic issues that affect most, if not all, career patterns of women scientists and engineers who choose to work in higher education. It is the generic issues that interventions are expected to address first and foremost (CWSE, 1991). And, as can be seen in Figure 6-2, interventions are necessary to increase the low percentage of S&E faculty who are women.

The "Glass Ceiling"

Many data are available to show that the rate of advancement of women in academe is significantly less than that of men, even when the comparison is normalized for educational background, years of professional experience, or research productivity (CWSE, 1991; Brush, 1991). This now incontestable fact indicates that an implicit barrier to advancement—a "glass ceiling"—exists for women faculty members. Given the persistent, low percentages of women who become tenured on science and engineering faculties, despite enlargement of the pool of female applicants for entry-level appointments, the tentative conclusion can be drawn that the "glass ceiling" operates at the associate professor rank in most research universities.

The "Rules of the Game"

Brush (1991) alludes to a network of expectations, conceptual dogmas, and social interactions that may underlie the functioning of academic departments on a daily basis and to which allegiance is required in order that

a faculty member achieve success. These unwritten "rules of the game" must become known to the aspiring assistant professor very soon after appointment to ensure a smooth passage to tenure. Aisenberg and Harrington (1988) have described poignantly how often the "rules of the game" go unlearned by women in academe until professional disaster strikes. They cite a series of homely counsels, distilled from many telling experiences, that can help to alleviate this problem: assume there will be opposition; be persistent; learn to say "no"; use contacts; choose your fights. Perhaps most revealing of the anecdotal information given to them about how to travel safely along the road to tenure was that provided by a woman newly-promoted to associate professor. "I was very lucky,'' she related, "to have a female chairperson who took me through tenure the way you would want a mother to stand by you as a guide, who really cared about you but wanted you to have your own independence" (Aisenberg and Harrington, 1988, p. 47).

The "Biological Clock"

Most of the recent literature on career patterns of women scientists and engineers reviews the perennial issue of the apparent conflict between the demands of motherhood (or other familial obligations) and those of the profession (Aisenberg and Harrington, 1988; Brush, 1991). This conflict has taken an especially acute form in the context of academe because of the requirements for tenure (CWSE, 1991). Although fast disappearing into retirement are the senior male professors who expound the antediluvian views that women faculty members with children dilute academic research productivity, or that women faculty members should not bear children, most universities do not function in practice as if these views were passé. Recognition of the "biological clock" and, more generally, of a faculty member's familial obligations is still treated as a variance to normal professional activity instead of as an integral part of it.

These three generic issues do not exhaust the tableau of problems that face women who choose careers in academe to do teaching and research in scientific or engineering fields. But they do surface repeatedly in a number of recent self-evaluations undertaken by major research universities to assess the academic environment for women on science faculties. The principal findings in these studies echo the concerns noted above:

-

With few exceptions women in science are but a small minority in their peer groups, and their

-

proportion drops sharply as they advance through their careers. The resulting isolation impedes research, increases stress, and may lead to abandonment of a scientific career.

-

The period when successful scientific careers are usually forged (in the general career pattern developed when the enterprise was almost exclusively male) corresponds to the period of childbearing.

-

Experimental work, which makes extraordinary demands on availability in time or location, raises conflicts with the family responsibilities that continue to be disproportionately borne by women.

-

Women graduate students are often dissuaded from pursuing certain areas of science. In some disciplines they are discouraged by faculty and student colleagues from pursuing mathematical or theoretical investigations; in other fields women are discouraged from pursuing experimental work (Wilson, 1992).

Recognition of these issues and their importance to the success or failure of women scientists in academe as part of the basis for designing interventions was one of the discussion themes at the Irvine conference. Such recognition can serve as a reference frame from which to evaluate the options and effectiveness of the model interventions that were presented at the Irvine conference and are summarized in the following sections.

Sample Interventions

Table 6-1 recapitulates key features of five interventions about which information was provided at the Irvine conference. Perusal of the table indicates that all the programs address enhancing the research capability and competitiveness of their targeted groups. Most of the programs are directed toward scientists and engineers who are in an early stage of their careers. Almost none of the programs are directed uniquely at women faculty members and some—indeed, half of those listed in the table—have no emphasis on women at all. In this respect, the programs of the National Sci

ence Foundation (NSF) perhaps deserve a more detailed exposition, since they contain at least a specific reference to women faculty.

Programs at NSF

Visiting Professorships for Women (VPW). This program provides opportunities for postdoctoral women engineers and scientists who (1) work in the disciplines supported by NSF, (2) are employed in industry, government, professional associations, and academic institutions, or (3) are established, published, independent scholars to advance their careers via independent research and to serve as role models and provide motivation, guidance, and encouragement for women students to pursue careers in science and engineering. The VPW program enables women scientists and engineers to undertake research and other activities, including teaching, at host academic institutions in the United States, its possessions, or territories. These may be either universities or four-year colleges where the necessary facilities and resources can be made available. The visiting professor's activities should:

-

contribute to the body of scientific knowledge through her research,

-

enhance the research and instructional programs of the host institution,

-

affect women students at the host institution who may be planning careers in science and engineering, and

-

benefit the home institution by increasing the skills of the returning staff member.

The research may be conducted independently or in collaboration with others, but more than half of the award period should be spent on the research activities.

The visiting professor is expected to serve as a role model and provide explicit guidance and encouragement to other women seeking to pursue careers in science or engineering. She undertakes teaching, counseling and mentoring, and/or other interactive outreach activities to increase the visibility of women scientists and engineers in the academic environment of the host institution, and to demonstrate to students opportunities for careers in science and engineering. These interactive activities may be at the undergraduate or graduate level, be directed to the community at large, or involve some combination of such activities.

TABLE 6-1: Summary Features of Some Targeted Intervention Programs

|

Program and Supporting Agency |

|

◆ National Science Foundation (Klein, 1991) |

|

Visiting Professorships (VPW) |

|

Faculty Awards (FAW) |

|

Career Advancement Awards (CAA) |

|

Research Planning Grants (RPG) |

|

◆ University of California (Cota-Robles and González, 1991) |

|

President's Postdoctoral Fellowships |

|

Academic Career Development Program for Minorities and Women |

|

◆ National Institute of General Medical Sciences (Maddox, 1991) |

|

Minority Biomedical Research Support (MBRS) |

|

Minority Access to Research Careers (MARC) |

|

◆ National Aeronautics and Space Administration (McGee, 1991) |

|

Resident Research Associateships |

|

Summer Faculty Fellowships |

|

◆ Department of Veterans Affairs (Hays, 1991) |

|

Research Career Development |

|

Designed To Enhance Career Opportunities in Science and Engineering |

|

|

Targeted Groups |

Relevance to Women in Academe |

|

Women scientists and engineers |

Enhance research skills and role modeling |

|

Tenured women faculty in science and engineering |

Research support for ''outstanding women faculty" |

|

Experienced women faculty scientists and engineers |

Enhance research career potential |

|

Women scientists and engineers |

Facilitate competitive research proposals |

|

Women and racial or ethnic minorities |

Enhance competitiveness for faculty appointment in universities and colleges |

|

Women and racial or ethnic minorities |

Prepare for academic careers |

|

Faculty at institutions with substantial minority enrollments |

No special emphasis |

|

Students and faculty at institutions with substantial minority enrollemnt |

No special emphasis |

|

Postdoctoral scientists and engineers |

No direct relevance |

|

Recently-appointed faculty at teaching institutions |

No direct relevance |

|

Medical clinicians and investigators |

No direct relevance |

Faculty Awards for Women (FAW). This program recognizes "outstanding women faculty" nominated by their academic institutions through the provision of research awards. Nominees must be tenured but not hold the rank of professor. In FY 1991, 601 nominations were received and 100 awards were made. The number of nominations represents about 8% of the female associate professors in science and engineering in the United States. About 80% of the awards were roughly equally divided among the physical sciences, biological sciences, and engineering, with the remaining 20% shared by geological and computer sciences.

Career Advancement Awards (CAA). This program—open to experienced, postdoctoral investigators who are scientists and engineers—is designed to expand research opportunities for women by helping researchers acquire expertise in new areas to enhance their research capability and by assisting those who have had a significant research career interruption to acquire "updating" for re-entry into their respective fields. Awards may be used for salary (summer and release time, if it can be justified), professional travel, consultant fees, research assistants, and other research-related expenses, including equipment. Eligibility is limited to women scientists and engineers in an NSF-supported field who hold faculty (not necessarily tenure-track) or research-related positions in U.S. colleges, universities, or related institutions and have had some prior independent research experience as principal investigators or project leaders.

Research Planning Grants (RPG). This program, on the other hand, is designed to increase the number of new women investigators participating in NSF research programs and to facilitate preliminary studies and other activities related to the development of competitive research projects and proposals by women who have not previously had independent federal research funding. These are one-time awards that may be used for preliminary work to determine the feasibility of a proposed line of inquiry and/or for other activities that will facilitate proposal development. These awards may include summer salary; released time; professional travel; consultant fees; and other research-related expenses that would enhance the quality of the proposed research.

Other Interventions

President's Postdoctoral Fellowship Program. This program, initiated in 1984 by the Office of the President of the University of California, was

designed to increase the competitiveness of women and racial or ethnic minority Ph.D. degree recipients for faculty appointments at the University of California and other major institutions of higher education (Cota-Robles and González, 1991). The program currently offers up to two years of support for postdoctoral research for each of 20 new Fellows per year. Each Fellow has a faculty sponsor who provides mentoring and guidance and who helps promote the Fellows visibility among colleagues on other campuses.

Since the program began, 1,455 persons have applied for President's Fellowships. Of these applicants, 138 have received fellowships, 76 of them women. As of 1991, 98 Fellows had completed the two-year program; 52 of them, of whom 31 are women, had obtained tenure-track appointments at universities.

Academic Career Development Program (ACDP). Another program instituted throughout the University of California system to prepare women and minorities for careers in academe is the ACDP, "an integrated program of support" having four components: (1) Graduate Outreach and Recruitment, (2) Graduate Mentorship Awards, (3) Research Assistantships/Mentorships, and (4) Dissertation-Year Fellowships (University of California, 1991). Each component focuses on a particular activity to enhance graduate retention and promote academic careers:

-

Graduate Outreach and Recruitment: Potential students visit and participate in summer internship programs in university departments. In 1990, 226 undergraduates from the University of California (UC), 43 from California State University, and 137 from other institutions participated in the summer programs at all nine UC campuses.

-

Graduate Mentorship Awards: Outstanding minority and women Ph.D. students work with faculty mentors in selecting courses of study and developing dissertation topics. In academic year 1990–91, all 67 students who had received awards in 1989–90 continued the program, along with 68 starting the first of two years.

-

Graduate Research Assistantship/Mentorship Program: Minority and women graduate students work half-time as research assistants, reducing their reliance on loans and providing opportunities for them to engage in intensive research. In academic year 1989–90, 100 women and minority graduate students participated in this program; 104 were enrolled in 1990–91.

-

Dissertation-Year Fellowship Program: An annual stipend of $12,000

-

plus $500 for research expenses enables women and minorities who are Ph.D. candidates to complete their theses and prepare for faculty teaching positions. Since 1986, 177 students (68 men and 109 women) have received these fellowships. Of the 84 fellows who have earned their Ph.D.s, 38 have received tenure-track positions, and 21 are pursuing postdoctoral research.

Although the program is relatively new, initial evaluations of each component have indicated their success in helping the University of California to attract outstanding students from throughout the country (University of California, 1991).

Minority Biomedical Research Support (MBRS). This program of the National Institute of General Medical Sciences focuses on increasing the number of minority biomedical research scientists and on the recruitment of underrepresented minorities into undergraduate and graduate science programs (Maddox, 1991). Experience with these programs suggests that recruitment efforts designed to encourage and increase underrepresented populations into the sciences are not only similar, but, perhaps, universal. Thus, it may be possible to utilize the same approach to enhance specifically the number of women in the sciences. Prior to the availability of MBRS grants, members of minority science faculties in the Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) were not encouraged to apply for federal research funds. Many had received doctoral training in majority institutions under professors who had federally funded grants but, when these minority scientists assumed faculty positions at an HBCU, a variety of factors operated against continuation of their research interests through independently sponsored projects. A combination of long teaching hours, lack of modern facilities and equipment, lack of information about funding sources, lack of grantsmanship and guidance in seeking funding, and, most of all, frustration, disillusionment and lack of faith in the "the system" took their toll. Similar frustrations are experienced by women wishing to pursue careers in academe (Aisenberg and Harrington, 1988). It was through the efforts of several advocates for strengthening minority representation in education that the idea for the development of biomedical research support for predominately black colleges was conceptualized. The predominant funding instrument, the traditional MBRS grant, is awarded to faculty members at qualifying institutions (two-and four-year colleges) for biomedical research projects that employ students, both undergraduate and graduate, as part of the supported

research team. A special feature of the traditional MBRS grant is the participation of Associate Investigator Institutions. These are majority institutions that grant the Ph.D. degree and have established investigators with National Institutes of Health (NIH) support who are eager to work either with students at an HBCU or with minority students at their own institution. These investigators participate in the MBRS grant, but receive funds only for student-related costs. In addition, the program offers support for certain types of renovation projects and the purchase of research equipment.

Evaluations of the MBRS program has shown its effectiveness in recruiting minority students to careers in scientific research (see, for example, Garrison and Brown, 1985).

On Target for Women?

The interventions summarized in Table 6-1 vary widely in their relevance to women faculty in science and engineering. On the one hand, NASA sponsors only pre-baccalaureate programs targeted to women, and its faculty research programs, like those of the Department of Veterans Affairs, not only do not place any special emphasis on women, but may even be structured so rigidly vis-à-vis work hours and child care issues that they actually inhibit participation by female professors (McGee, 1991; Hays, 1991). On the other hand, the NSF programs, although structured and administered like any other of its research opportunity programs, are targeted directly to women scientists and engineers, in some cases to junior faculty members whose research experience is limited (CAA and RPG programs). Still other programs (President's Fellowships and MBRS programs) offer advantages to women contemplating academic careers while not targeting them specifically. It appears that none of the programs summarized in Table 6-1 were designed by women faculty members for women faculty members, existing or prospective (Sposito, 1991). In this respect, it can be said that, effectively, no programs of major proportions are available solely to promote the careers of women scientists and engineers in academe.

To what degree is this statement an unfair judgment? It is not unfair as a conclusion in respect to the highly competitive, time-demanding, federal research enhancement programs whose structuring simply ignores the multifaceted lifestyle of women professors (Aisenberg and Harrington, 1988) in favor of a one-dimensional ideal of the scientist-academic as workaholic and polemist extraordinaire (Brush, 1991). Indeed, as Linda Wilson (1992)

pointed out in her recent testimony before the House Subcommittee on Employment Opportunities,

More subtle forms of discrimination also continue, including, for example, treatment of women as outsiders and negative attitudes of faculty toward women's family commitments. The male dominance of the tenured science faculty in major research universities results in many non-tenured women feeling powerless. Many non-tenured women do not have positive, collegial relationships with senior members of their departments and are deprived of the mentoring relationships that are often critical to advancement in a field. In some cases, junior faculty feel exploited; and in many cases, women perceive their situations to be worse than those of their male junior colleagues. The failure to integrate junior faculty within their own department has been a long-standing problem in some cases.

Many institutions have recently undertaken studies of access and the environment for women. These efforts are commendable, but the studies frequently show that the same barriers and problems found in similar reviews 20 years ago still persist.

Most of these problems reflect a culture that has insufficiently recognized the, capabilities and contributions of women and their potential, a culture that has not kept pace with women's changing employment patterns and society's increasing need for women scientists' talent. These problems are a result of our tendency to imagine the ideal scientist as a man who can single-mindedly devote 80 hours a week to science because he has no conflicting familial obligations.

It is unfair, however, to overlook the essential, positive features of some programs that, although not addressing directly the three generic issues raised above, do contain ingredients with which a successful approach to promoting the careers of women faculty members can be fashioned:

-

mentoring, said repeatedly in the Irvine conference to be critical (and

-

always successful experientially, if not strictly in professional terms) to achieving the self-confidence necessary for realizing the goals of any enhancement program;

-

networking, communicating frequently with peers in order to ''find out what's going on," gain political skills, and obtain continual reassurance that the difficulties one faces are not unique or insurmountable; and

-

strongly supportive top management, without which programs to enhance the careers of women faculty are doomed to be short-term, under-financed, and subject to inconsistent resource allocations that actually signal low institutional commitment. It is well to remember that statements from an administration about resource availability are actually statements about the relative priorities of the administration.

Women are not being appointed at expected rates or promoted to expected levels. Among the reasons given for the slow and low rates of women's advancement up the academic career ladder in science and engineering are the following: geographic constraints on dual-career families, narrowness of searches to fill faculty openings, fears that the department will not be getting its due because of family commitments, and lack of "top-down" support within the institution.

Future Directions

Given the disappointing paucity of major interventions to promote the careers of women scientists and engineers in academe, the Irvine conference discussion focused on strategies to develop these programs at the university level. Following are four broad strategies whose implementation by universities would do much to address the three generic issues described above:

-

Establish an Office on the Status of Women Faculty Members, whose director is a senior female professor with line responsibility to the chief administrative officer of the campus.

The responsibilities of the director should include:

-

data-taking and monitoring regarding all appointments, merit advancements, and grievance claims of women faculty members;

-

facilitating networking among women faculty members on the campus; and

-

designing (with the help of tenured women faculty members) and implementing mentored interventions for untenured women faculty members.

-

Revise the tenure process on campus.

The faculty governing body (academic senate) on campus should revise the tenure process to ensure that untenured women faculty members are indeed reviewed by their peers during the probationary period. "Peer review" does not simply constitute an evaluation of the prima facie productivity and quality of research or teaching. It means an evaluation based on a deep, palpable understanding of what it means experientially to be a woman on the faculty. This kind of understanding among male faculty members has long been a facet of their tenure review processes. The same tacit, mutual sharing of academic and social values must now be ensured to occur for women faculty members, and this cannot happen until every tenure-review committee has at least one female member. Brush (1991) has described other reforms of the probationary process that will ensure that women are treated equitably, most of them having to do with their family responsibilities. The University of California (1991) recently has began to explore a much broader definition of the criteria for merit advancement that goes a long way toward reforming the tenure process in research universities. It specifically recognizes mentoring of students or junior faculty by professors as an integral part of the teaching responsibility and the reward structure.

-

Create a family-friendly workplace environment.

The chief administrative officer of the campus must recognize officially the fundamental role that family plays in the lives of women and men faculty members by taking steps to ensure as full an integration as possible of family and professional responsibilities in the workplace environment. Professors who are women (or men, for that matter) must no longer have to endure extraordinary stress in their daily lives by attempting to meet these responsibilities in a work environment that wishes to pretend that only narrowly-defined professional activities are important (Aisenberg and Harrington, 1988). As one Irvine conference attendee put it, "The time is over when faculty members who are new mothers should have to hide the breast

-

pump under their desks." Steps must be taken to establish flexible work schedules, job sharing, and fully subsidized, proximate child care as standard features of campus programs for the faculty.

-

Allow maximum flexibility in working conditions, consistent with carrying out responsibilities of teaching and research.

As pointed out during the discussions of both academic and industrial employment at the CWSE Conference on Science and Engineering Programs, greater flexibility may require additional expense but should be cost-effective in terms of the productivity of S&E employees. Universities could be expected to profit by implementation of some practices, such as offering flexible benefits packages, becoming more common in industry.

REFERENCES

Aisenberg, N., and M. Harrington. 1988. Women of Academe. Outsiders in the Sacred Grove. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

Brush, Stephen G. 1991. Women in science and engineering. American Scientist 79:404–419.

Committee on Women in Science and Engineering (CWSE). 1991. Women in Science and Engineering. Increasing Their Numbers in the 1990s . Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Cota-Robles, Eugene H. 1991. Personal communication, November 4,1991.

____, and J. González. 1991. The President's Postdoctoral Fellowship Program. Paper presented at the National Research Council conference on "Science and Engineering Programs: On Target for Women?" Irvine, CA, November 4–5.

Garrison, Howard H., and Prudence W. Brown. 1985. Minority Access to Research Careers. An Evaluation of the Honors Undergraduate Research Training Program. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Hays, Marguerite T. 1991. The VA's Research Career Development Program as an Opportunity for Women to Enter Medical Research. Paper presented at the National Research Council conference on "Science and Engineering Programs: On Target for Women?" Irvine, CA, November 4–5.

Hoffman, Paul (ed.). 1991. Discover 12(10). Special Issue: A Celebration of Women in Science. New York: The Walt Disney Company.

Klein, Margrete S. 1991. NSF Programs for Women. Paper prepared for the National Research Council conference on "Science and Engineering Programs: On Target for Women?" Irvine, CA, November 4–5.

Maddox, Yvonne T. 1991. Promoting Careers in Academe: National Institute of General Medical Sciences Minority Programs. Paper presented at the National Research Council conference on "Science and Engineering Programs: On Target for Women?" Irvine, CA, November 4–5.

McGee, Sherri. 1991. Promoting Careers in Academe: Opportunities at NASA for College and University Faculty. Paper presented at the National Research Council conference on "Science and Engineering Programs: On Target for Women?" Irvine, CA, November 4–5.

Sposito, Garrison. 1991. Personal communication with participants at the conference, "Science and Engineering Programs: On Target for Women?" Irvine, CA, November 4–5.

University of California (UC), Office of the President. 1991. Report on Affirmative Action Programs for University Academic Employees and Graduate and Professional Students. UC: Oakland.

Wilson, Linda S. 1992. Testimony during the Oversight Hearing on Sexual Harassment in Non-Traditional Occupations, United States House of Representatives, Committee on Education and Labor, Subcommittee on Employment Opportunities, Washington, DC, June 25.