The 2012 National Research Council report Disaster Resilience: A National Imperative highlighted the challenges of increasing national resilience in the United States. The report, sponsored by eight federal agencies and a community resilience organization, was national in scope and extended to stakeholders beyond the Washington, D.C. governmental community to recognize that experiential information necessary to understand national resilience lies in communities across the United States.1 One finding issued by the committee was that “without numerical means of assessing resilience, it would be impossible to identify the priority needs for improvement, to monitor changes, to show that resilience had improved, or to compare the benefits of increasing resilience with the associated costs.”

Although measuring resilience is a challenge, measures and indicators to evaluate progress, and the data necessary to establish those measures, are critical for helping communities to clarify and formalize what the concept of resilience means for them, and to support efforts to develop and prioritize resilience investments. In the NRC (2012) report, the committee reviewed the strengths and challenges of different frameworks for measuring resilience, and identified four critical dimensions of a consistent system of resilience indicators or measures:

- Vulnerable Populations—factors that capture special needs of individuals and groups, related to components such as minority status, health issues, mobility, and socioeconomic status

- Critical and Environmental Infrastructure—the ability of critical and environmental infrastructure to recover from events—components may include water and sewage, transportation, power, communications, and natural infrastructure

- Social Factors—factors that enhance or limit a community’s ability to recover, including components such as social capital, education, language, governance, financial structures, culture, and workforce

- Built Infrastructure—the ability of built infrastructure to withstand impacts of disasters, including components such as hospitals, local government, emergency response facilities, schools, homes and businesses, bridges, and roads

The United States does not currently have a consistent basis for measuring resilience that includes all of these dimensions, making it difficult for communities to monitor improvements or changes in their resilience. One of the recommendations from the 2012 report stated that government entities at federal, state, and local levels, and professional organizations should partner to help develop a framework—the report suggested the word “scorecard”—for communities to adapt to their circumstances and begin to track their progress toward increasing resilience.

______________

1Sponsors included the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, U.S. Department of Energy, U.S. Department of Commerce National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Department of Homeland Security and Federal Emergency Management Agency, Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, and the Oak Ridge National Laboratory/Community and Regional Resilience Institute.

To build upon this recommendation and begin to help communities formulate such a framework, the Resilient America Roundtable of the National Academies convened the workshop Measures of Community Resilience: From Lessons Learned to Lessons Applied on September 5, 2014 in Washington, D.C. The mission of the Resilient America Roundtable is to convene experts from the academic, public, and private sectors to design or catalyze activities that build resilience to extreme events. The Roundtable provides a venue for current research, science, and evidence-based foundations to inform whole community strategies for building resilience. This workshop’s overarching objective was to begin to develop a framework of measures and indicators that could support community efforts to increase their resilience. The framework will be further developed through feedback and testing in pilot and other partner communities that are working with the Resilient America Roundtable. The workshop was structured around three broad questions:

- What is the value of resilience?

- How do I know that my investments are going to increase my resilience?

- How can measures/indicators be scaled and adapted to different frames of reference (e.g., community to community; nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) to business; citizen to elected official)?

In addition to the planning committee, the workshop included representatives from the federal government, private sector and businesses, nongovernmental organizations, the academic community, and members of the Resilient America Roundtable. The workshop aimed to develop or frame measures and indicators, which could be applied across a range of communities, to support community efforts to place a meaningful value on resilience. Measuring real improvements is dependent, in part, on understanding baselines for various indicator categories; using measures can help communities see improvements in their resilience over time, better gauge and measure their investments, understand tradeoffs among community priorities, and assist decision makers in establishing incentives for increasing resilience (National Academy of Sciences, 2012).

Measuring Community Resilience: The Landscape of Resilience Indicators

Susan L. Cutter, Carolina Distinguished professor and director, Hazards and Vulnerability Research Institute, University of South Carolina and chair of the committee that wrote the NRC (2012) report started the workshop by describing the current landscape of resilience indicators and frameworks. Dr. Cutter stated that in addition to the efforts at the National Academies, resilience has recently gained a lot of attention, both nationally and internationally. Those working on resilience often struggle to define and measure it; however, the goal, Dr. Cutter stated, is to move from disaster risk reduction2 to a more sustainable future and for many, resilience is the mechanism that will facilitate that movement.

Dr. Cutter noted that there are many different definitions of resilience; the 2012 committee defined resilience as the “ability to prepare and plan for, absorb, recover from or more successfully adapt to actual or potential adverse events” (National Academy of Sciences, 2012). The challenge is not in drafting the definition of resilience, but rather in operationalizing that definition. A resilient community is one in which people are able to adapt to changing conditions and assess if that adaptation is appropriate for the place (e.g., building on sand knowing it may be windblown or washed away with coastal flooding).

______________

2The United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNISDR) defines disaster risk reduction as the concept and practice of reducing disaster risks through systematic efforts to analyze and reduce the causal factors of disasters. Reducing exposure to hazards, lessening vulnerability of people and property, wise management of land and the environment, and improving preparedness and early warning for adverse events are all examples of disaster risk reduction. Additional information can be found at: http://www.unisdr.org/who-we-are/what-is-drr.

In order to perform such an assessment, Dr. Cutter stated, communities need to be able to measure their resilience. Communities are often located in high hazard areas. For example the community of Seabright in New Jersey is located between the Atlantic Ocean and the Navesink River on a barrier island that is not much more than two houses wide; in 2012, the community was devastated by Hurricane Sandy. Dr. Cutter offered that Seabright is an example of a community that needs to measure its resilience in order to understand its capacity to respond to, recover from, and adapt to adverse events. Part of that adaptation may be to move away from the coast, an option that more coastal communities are starting to consider as they recognize the increased risk of adverse events occurring in proximity to the coastline.

A tool to measure resilience can help communities assess their priorities, goals, and needs, and also help establish baselines. Baselines are needed to better assess progress and to set goals in order to allocate resources. A mechanism is also needed to help understand investments made to improve resilience, added Dr. Cutter, especially since such investments can be of considerable size for many communities. Such a mechanism could also be used to evaluate different intervention options to improve and enhance resilience.

Dr. Cutter said that the 2012 Disaster Resilience report outlined 17 assessment tools and systems, and that in the two years since the report was released there has been an explosion in the number of additional resilience measuring tools developed by government agencies, academia, NGOs, communities, and the private sector. These tools vary in range and purpose—top-down to bottom-up, qualitative to quantitative, hazard specific to hazard-neutral, local to global, and pre- to post-event. Because there are so many assessment tools available, the challenge to communities is how to navigate the landscape and identify the right tool or combination of tools to meet their needs.

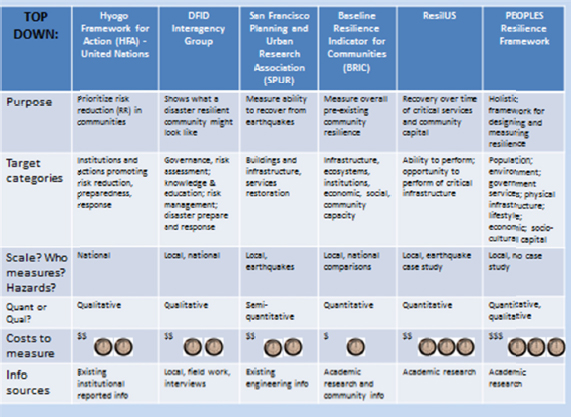

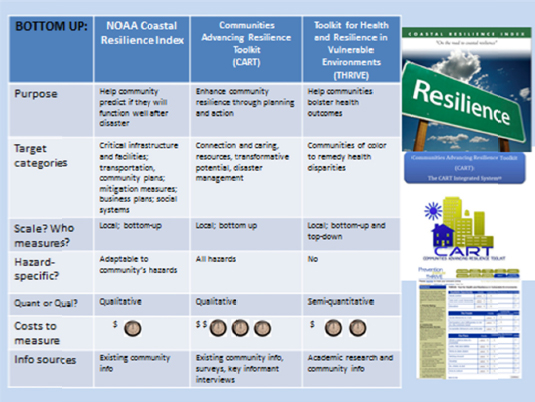

Dr. Cutter provided a table with a series of examples of tools grouped into those that are top-down and those that are bottom-up (Table 1-1 & 1-2). Top-down tools are developed by an organization external to a community using academic or institutional data with little community involvement. Developing bottom-up tools generally includes the coproduction of knowledge that occurs when the community is engaged in the process.

TABLE 1-1 Top Down Approaches & Indexes for building resilience. Prepared by NRC staff.

TABLE 1-2 Bottom Up Approaches & Indexes for building resilience. Prepared by NRC staff.

Top-down tools are often intended for use by an oversight body or require external expertise—a government office or an academic entity, for example—to help a community measure different aspects of their resilience to inform decision making. Dr. Cutter noted that the purpose, scale, and target of these top-down approaches vary, and outlined several examples. The Hyogo Framework for Action (HFA) from the United Nations is a qualitative model that prioritizes risk reduction activities across different nation states.3 ResilUS quantitatively assesses the recovery of critical services within a community4. The San Francisco Planning and Urban Research Association (SPUR) model is semi-quantitative and infrastructure-focused, and assesses the ability of a community’s infrastructure to recover from earthquakes.5 The PEOPLES Resilience Framework is a quantitative and qualitative holistic framework for designing and measuring resilience at the local level,6 which uses a GIS-based assessment that incorporates different elements of resilience into a single inventory. The Baseline Resilience Indicators for Communities (BRIC) is a quantitative measure of overall pre-existing community resilience at the county level designed to compare counties across the United States.7 The BRIC index assesses the inherent characteristics of a community that contribute to resilience, such as social and economic capital, ecosystems, infrastructure, and institutional capacity. This information is developed into six indicators that can be used to compare communities across the United States. Dr. Cutter explained that deconstructing the BRIC index allows for the analysis of the driving components—social, economic, community, and institutional capacity—that vary geographically, just as resilience as a whole varies geographically.

______________

3Available at: www.unisdr.org/we/coordinate/hfa

4Available at: https://huxley.wwu.edu/ri/resilus

5Available at: http://www.spur.org/

6Available at: http://peoplesresilience.org

7Cutter, Susan L.; Burton, Christopher G.; and Emrich, Christopher T. (2010) "Disaster Resilience Indicators for Benchmarking Baseline Conditions, Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management: Vol. 7: Iss. 1, Article 51.

Dr. Cutter also presented bottom-up tools, which are locally based and locally driven indexes and models. One example is the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Coastal Resilience Index,8 designed to help communities predict how well they would function following a disaster. It consists of a scorecard completed by a community as a qualitative self-assessment that evaluates critical infrastructure and facilities, hazard mitigation measures, and the community’s overall plan. The index is adaptable to the hazard context of that community; however, that community-specific element can make it a challenge to compare different communities. The Toolkit for Health and Resilience in Vulnerable Environments (THRIVE) was initially developed to help communities of color bolster their health outcomes and remedy health disparities.9 This tool is a combination of a self-assessment and quantitative information, and is a bottom-up assessment coupled with a top-down assessment. The Communities Advancing Resilience Toolkit (CART), a product of the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorist and Response to Terrorism (START),10 focuses on enhancing a community’s resilience through planning and action, with an emphasis on building and sustaining connections within communities. This tool requires a lot of time and effort at the local level to implement, but applies to all hazards and includes elements of community information gathered from statistical analysis, surveys, and key informant interviews.

Dr. Cutter stated that in reviewing community tools, the 2012 committee developed overarching principles that every tool should contain, including:

- Openness and transparency

- Alignment with the community’s goals and visions

- Measures that:

- Are simple and well documented (evidence-based)

- Can be replicated

- Can address multiple hazards

- Are representative of a community’s geographical extent, physical characteristics, and diversity

- Are adaptable and scalable to different community sizes, compositions, and changing circumstances.

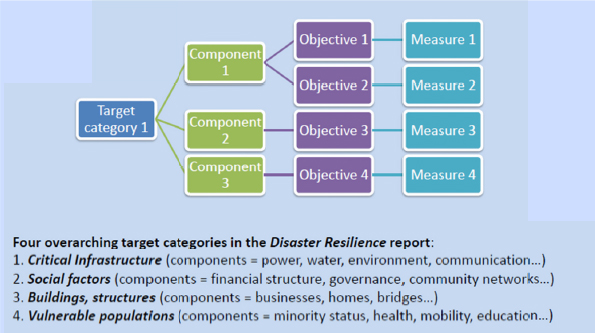

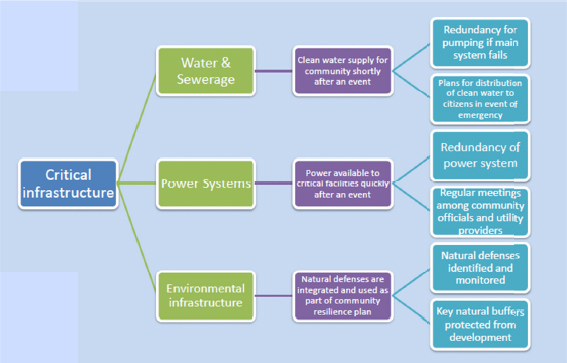

Four overarching target categories for developing community-based resilience measures are identified in the 2012 Disaster Resilience report: critical infrastructure, social factors, buildings and structures, and vulnerable populations (Figure 1-1). Communities are a system of systems, Dr. Cutter offered. The components in those systems, however, are often assessed individually because it is easier to understand the measure of a single component than it is to measure and understand all the connectivity and interdependencies within the system as a whole. Communities need to understand and measure the entire system in order to fully implement resilience. Dr. Cutter described the process of developing a measuring tool as beginning with the identification of a target category, such as critical infrastructure, followed by identifying a list of several key components for that community in that target category. Objectives for those components must then be established before ultimately identifying measures for those objectives. For example, water and sewage, power systems, and environmental infrastructure are components of critical infrastructure (Figure 1-2). A clean water supply is an example of an objective for the water and sewage component.

Dr. Cutter reinforced the many reasons why communities need to increase resilience:

- Saves lives and money needed to respond to a disaster by taking action before an event occurs, and builds stronger, safer, and more secure communities

- Helps in understanding current levels of exposure and potential impacts from adverse events, thereby helping a community take responsibility for its own disaster risk

______________

8Available at: http://masgc.org/coastal-storms-program/resilience-index

9Available at: http://thrive.preventioninstitute.org/thrive/index.php

10Available at: www.start.umd.edu/research-projects/community-assessment-resilience-tool-cart

- Allows for identification of the community’s capacity to cope with adverse effects and where improvements are needed

- Fosters a culture of self-sufficiency, helping-behavior, and betterment

- Fosters cooperation among all members of the community

FIGURE 1-1 Four overarching target categories, components, objectives, and measures used in identifying elements for community resilience. SOURCE: Dr. Susan Cutter, presentation, September 5, 2014, Washington, D.C.

FIGURE 1-2 An example of components, objectives, and measures identified using the critical infrastructure target category. SOURCE: Dr. Susan Cutter, presentation, September 5, 2014, Washington D.C.

In addition, communities need a resilience measures tool that can:

- Assess and help prioritize needs and goals

- Establish baselines for monitoring progress and recognizing success

- Evaluate costs (investments) and benefits (results)

- Assess the effects of different policies and approaches

Dr. Cutter concluded by stating that a single, one-size measure for all facets of resilience is unlikely to work because the goals and aspirations, compositions, and threats and hazards of communities are different. Rather, a suite of tools with several indicators is needed. Many tools have been developed; however, few are actually used by communities because they are too complex, too computationally intensive, or too simple and do not provide the right information. These tools need to be adjusted and modified to fit communities’ needs, as well as be promoted in a way that makes the business case for why resilience is important.

Question & Answers

A member of the audience asked about how hazard and disaster planning are different from identifying measures. Dr. Cutter clarified that planning includes measures and indicators, and involves assessing the physical infrastructure and land used for zoning, but does not necessarily take into account the adaptive capacity, the social networks, or the perceptions of the community with respect to risk. Planning is a tool that can be used to help achieve resilience, but resilience is a much broader framework. Similarly, mitigation is a tool that can be used to achieve resilience, but does not take into account different elements within a community that are important in achieving resilience. Leadership, for example, is an element not accounted for under planning or mitigation yet is an integral part of why some communities are more resilient than others.

Another member of the audience asked about the incorporation of temporal scales into the use of measures or indicators. Dr. Cutter responded that the interval between the use of measures is how the temporal scale is generally addressed. The BRIC index, for example, was measured in 2000 and again in 2005, which allowed for the progression over time to show changes in the inherent resilience (inherent characteristics of a community that contribute to resilience include social and economic capital, ecosystems, infrastructure, and institutional capacity) of the regions assessed. Once there is a consistent measure, Dr. Cutter stated, it can be implemented in a timeframe that allows for the evaluation of changes over time—either short- or long-term; the drivers causing those changes can then be identified by the community. Often the occurrence of a large event, such as a hurricane, provides an explanation for the changes that have occurred; incorporating the temporal scale is important in order to understand that timeframe clearly.

Dr. Cutter was asked about including risk as part of measures and indicators as opposed to just resilience—a relative versus absolute measure of resilience. She explained that the BRIC index, for example, describes the inherent resilience in a community irrespective of the risk. Risk would need to be overlain by a resilience layer in order to assess the intersection of risk with resilience. Some locations may have elements that result in them having high resilience, but may also have high risk for a natural disaster, such as being in proximity to a coastline. This highlights the ongoing challenge of choosing measures and indicators, because the BRIC index, for example, was not designed to assess risk. It was designed to evaluate those characteristics in communities that can help them move towards resilience irrespective of risk.

A final question was asked about future steps that could help to clarify the landscape of the different tools and measures available to communities. Dr. Cutter responded that one of the objectives of the Resilient America Roundtable is to partner with pilot communities to begin the process of identifying critical elements of different tools and make those tools more accessible, to help communities prioritize resources and better reach their resilience goals.

REFERENCES

National Academy of Sciences. 2012. Disaster Resilience: A National Imperative. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.