4

Developing a Decision-Making Framework

Following the panel discussions, participants were divided into breakout groups. The groups corresponded to four overarching categories that the 2012 Disaster Resilience report recommended any index of resilience measures or indicators should include:

- Vulnerable Populations

- Critical and Environmental Infrastructure

- Social Factors

- Built Infrastructure

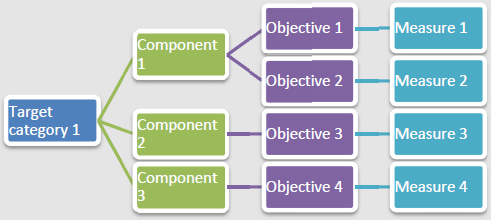

Each breakout group was tasked with identifying up to five key components within their category and providing objectives and goals for each component that could then be used to discuss specific resilience measures (See Box 4-1 for detailed instructions). Breakout groups were made up of participants at the workshop from diverse backgrounds, including academics and researchers, local decision makers and practitioners, and representatives from federal agencies, NGO’s, and the private sector. Effort was made to put together balanced groups that included experts in fields and disciplines directly related to the particular categories, as well as participants who work in other areas related to resilience that could provide alternate perspectives to the discussion. Using this workflow, each group was asked to develop a simple, hazard-neutral framework that could serve as a starting point for any community to begin to develop its own resilience measures. Tables with key points from each group’s discussion can be found in Appendix A.

Group One: Vulnerable Communities

The Vulnerable Communities breakout group began with the approach of trying to identify components as specific socially vulnerable groups, such as seniors, children, racial and ethnic minorities, low-income populations, non-English speakers, the homeless, the medically dependent, mobility impaired, persons in nursing homes, and persons with drug addictions. From the initial discussion, Group One discovered that this list of community groups did not provide the necessary overarching characteristics that would lead them to articulation of useful objectives. To address this issue, Group One identified characteristics that rendered certain population groups vulnerable through components that are based on the functional needs of an individual. For example, a person with special medical needs could be considered part of a vulnerable population if that individual had special communication needs, lacked independence, or required medical supervision. Other examples could include populations with transportation dependency, or that lack social and economic resources.

After identifying a series of components (see Appendix A), the group used the example of communication needs to begin to identify objectives for that component. Three objectives that were articulated included a) measuring the number of people in a community with special communication needs, b) identifying mechanisms to address communication needs with those who have a limited ability to receive or understand information, and c) identifying resources to assist these community members. Some of the representative communities that could be considered vulnerable due to communication needs included those who are non-English speaking, deaf/hearing-impaired, vision-impaired, illiterate, undocumented or documented immigrants, tourists, and/or students.

BOX 4-1 Breakout Group Instructions

The goal for each of the breakout group was to develop a simple, hazard-neutral framework to serve as a starting point for communities to begin to develop their own resilience measures. Workshop participants were divided into four pre-assigned groups, with 15 participants in each group. The breakout topics, based on the NRC report, Disaster Resilience: A National Imperative, represent four overarching categories fundamental to developing resilience indicators and measures (2012).

- Vulnerable Populations—factors that capture special needs of individuals and groups, related to components such as minority status, health issues, mobility, and socioeconomic status

- Critical and Environmental Infrastructure—the ability of critical and environmental infrastructure to recover from events, components may include water and sewage, transportation, power, communications, and natural infrastructure

- Social Factors—factors that enhance or limit a community’s ability to recover, including components such as social capital, education, language, governance, financial structures, culture, and workforce

- Built Infrastructure—the ability of built infrastructure to withstand impacts of disasters—including components such as hospitals, local government, emergency response facilities, schools, homes and businesses, bridges, and roads

A moderator and rapporteur facilitated and recorded the discussions. Each group was provided a workflow schematic (based on Dr. Susan Cutter’s presentation) with additional guidance to help frame the discussions. The workflow for each breakout group entailed identifying key components within that category and objectives/goals for each component that can then be used to discuss specific resilience measures.

Workflow Schematic

Basic Guidelines

Resilience measures should be:

- Open and transparent

- Replicable

- Well documented

- Simple enough to be used by a wide range of stakeholders

Approach to measuring resilience should:

- Address multiple hazards, and be adaptable to the specific communities and hazards they face

- Be place-based, rather than spatial and capable of dealing with a range of community sizes

- Be adaptable

Knowledge and Data questions to consider:

- What should be measured over what timeframe and geographic scale?

- Should resilience be assessed regularly or triggered by something?

- Should they be prescribed and uniform, or adapted for specific circumstances?

- Measured qualitatively or quantitatively?

Each group was provided a blank table (see below) in which to record the salient points of their discussion. The moderator and rapporteur were responsible for obtaining group input and recording it on two slides that were shared in the plenary session summary following the breakouts groups (Appendix A). Breakout group participants were specifically asked to:

- Identify up to 5 key components within each primary category.

- Identify up to 3 objectives (as statements or questions) for each of the components.

- Identify 1-2 measures (qualitative or quantitative) that could be used to assess progress with each objective.

- Discuss data, costs, incentives, challenges for objectives and/or measures

- Discuss information/data required, how baselines can be developed, how often measures might be used, and who is responsible for measuring and follow up.

- Discuss potential costs of implementing improvements and making use of measures (financial, time, personnel costs).

- Discuss 1-2 key incentives to ensure progress with each objective/measure.

- Discuss challenges, barriers (and/or successes).

Sample Table:

| Components | Objectives | Measures/ Indicators | Data, Frequency, Responsibility | Costs | Incentives |

Through the process of formulating the table, the group felt that an additional column was needed—resilience goals—to address the broader issues associated with reducing vulnerability and enhancing the capacity of the community. For communication needs, four goals were identified:

- Develop flexibility in the community’s communication systems to deal with uncertain events

- Have alternative means of communication/redundancy in the community’s systems to provide information to vulnerable populations in case main systems are inoperable

- Develop a network of translators who could reach out to people with special communication needs

- Implement training for organizations/community groups to address special communication needs

Overall, the group felt that the table was a useful mechanism to begin the process of developing an approach to identify vulnerable populations in a community, articulating the needs of those populations, and developing objectives for meeting those needs. Although time constraints did not allow participants to identify specific measures and indicators, the process was an entry point to moving towards that end goal. Group One participants also experienced several challenges in moving through this process. First, they had difficulty in defining what it means to be part of a vulnerable or at-risk group; different people had different definitions depending on their frame of reference. Participants also found that components could be too all encompassing, yet exclusive of particular individuals at the same time, and it could be difficult to account for individuals who move in and out of the defined categories due to changing life circumstances. Lastly, overlapping language between resilience and emergency management posed a potential barrier to a community’s ability to move from a response-only approach to an adverse event toward one of building resilience for the community.

Finally, one of the results of this exercise was articulation of awareness that, because resilience issues are complex, trying to move a community too quickly into the details of identifying indicators and measures for specific components can rapidly become complicated and overwhelming. Group One struggled with finding a starting point and deciding whether to first address the components or measures; for communities, it was noted that the starting point could be an even more difficult conversation that might also be politically charged. Nevertheless, most of the group participants observed that measures were an important tool in supporting efforts to become more resilient.

Group Two: Critical and Environmental Infrastructure

The Critical and Environmental Infrastructure group took a different approach to the exercise. Group Two focused on identifying key components and developing objectives for each of those components. As with Group One, definitions posed a challenge, particularly with how to define environmental infrastructure. While most group members agreed on elements of the term critical infrastructure, the term “environmental” was much more broadly interpreted. The group gravitated towards interpreting it as ecosystem services and green infrastructure.

The group considered classical preparedness components, such as water, energy, communication, transportation, and public health/services; the fifth component was the environment. Components were considered in context of short-term and long-term needs, and objectives were developed based on the critical elements of each component that would need to be maintained for continuation of service.

For water, objectives included: a) quality for human consumption, and for commercial and sanitation; b) containment of water sewage and wastewater treatment, and to address disruptions of service and inventory; and c) inventory to ensure a sufficient supply of drinking water and distribution to the public. These objectives proved to be similar for other components. Energy, for example, also had the objective of reliability and accessibility, which again relates to inventory. Long-term concepts addressed in regards to energy related to alternative energy supplies and being less dependent on fossil fuels, and alternative energy sources or technologies as a mechanism to provide households or communities a level of independence.

Transportation had mobility, accessibility, evacuation preparedness, and reliability as objectives. For communication, Group Two focused on mass communication, which is the ability to send out warnings and alerts, person-to-person communication, emergency responders and 911 functionality, and ensuring commercial activities. The group had extensive discussion around the environment component, and many group members stated that protection of community assets, such as wetlands as a buffer against severe storms, was critical, as was consideration of the quality for human and ecosystem health, interdependence of regions, and overall quality of life for residents.

Group Two spent most of the breakout session trying to tease out the various objectives for the components. Definitional issues were an ongoing challenge for making progress in completing the table. Besides the term “environmental,” other major points of discussion included what resilience means for communities and the role of jurisdictional domains in terms of who controls critical infrastructure. Infrastructure related to energy and communication is often held by private sector entities, which raised many questions about how to account and embed that infrastructure into the resilience process. Discussion also focused on the importance of bringing in and engaging the private sector in the resilience conversation. Part of that conversation includes issues around data, and identifying what data are relevant to assessing the resilience of a given region.

Group Three: Social Factors

The Social Factors group reframed the discussion of components by examining what social factors were critical to preserve and protect a community from a resilience perspective—in essence, the identity of the community. Group Three members identified leadership as an essential component, but did not attribute solely to government leadership. Most group participants agreed that leadership is found in many

sectors and can take on different forms depending on the organization or entity taking the leadership role; it is important that those leaders have awareness of risk factors and are able to connect with leaders in other networks.

Another critical component was social connectedness and cohesion, which includes attachment to place and social networks. There are formal and informal connections among businesses, government, and community organizations, group members observed, which are necessary in building social cohesion across a community. Resourcefulness was also a key component, particularly in reference to workforce in sectors such as healthcare, emergency services, and the private sector. The group broadened workforce to include the retired and unemployed since those groups can contribute skills to the community. Another objective of resourcefulness was to reduce vulnerabilities and minimize displacement, which requires an assessment of each group’s composition, distribution, and economic robustness.

A third component was interdependencies, particularly in consideration of a network, or networks, rather than a linear set of connections. This includes networks that move from the individual to community to regional scales, and the infrastructure needed to support these networks. Group Three discussed cultural diversity, including preparedness, individual capacity, and self-reliance as important cultural elements, and understanding the social and economic diversity of communities. The final component was education and schools. Although related and inseparable concepts, many Group Three participants made a case for considering them as separate – schools as a physical location and education as the prerequisite for developing skills, understanding risk, and improving livelihoods in the community.

In implementation of measures to address these components, they said, the community would need to tap into people with prior disaster experience within the community and who have influence with decision makers. If a community experienced a recent event, it might be more open to taking steps to increase resilience. The group discussed measures or indicators as investments that yield both short-term and long-term benefits. Finally, Group Three explored economic incentives and using rating systems to help drive resilience actions and mobilize members of a community.

Group Four: The Built Environment

Group Four identified housing, businesses, community facilities (e.g., schools, public administration, prisons), and health care facilities as four critical components of the Built Environment. The group focused on four “Rs” as objectives for each component: robustness, resourcefulness, recovery, and redundancy. For housing, the group discussed the presence of building codes, the percentage of buildings that meet the codes, presence of processes to bring housing up to code, and baseline assessments of housing stock to assess quality. Another important metric would involve a community’s ability to enforce the building codes. Members of the group from city management stated that codes are great tools, but can be challenging to enforce. Other important measures include how much of the housing stock participates in insurance and insurance-related programs, and available grants and permits as incentives for taxpayers.

Group Four discussed measures for businesses in terms of establishing baseline conditions and awareness. How aware is the business community of their risk to loss of property, or disruption of services and revenue? In assessing the current state of businesses, employee engagement is a critical factor, as is how much businesses provide for their employees, such as daycare services. From a broader perspective, factors to consider include determining the size of the businesses (e.g., nationally versus locally owned), foot-based traffic vs. mostly an online presence, percentage of the community’s population employed, and continuity plans. Baseline conditions include the state of community facilities: are they up to code and usable as shelters? Finally, the group discussed healthcare and the concept of “health deserts”: do all parts of a community have access to hospitals, urgent care clinics, general primary care, and other health facilities?

Most Group Four members agreed that baseline conditions represented a key overarching theme for all built structures, including an understanding of the level of community activity within those buildings, which helps to assess how participatory a community is in general. This participatory characteristic relates to how

cohesive a community will be and how much “buy-in” residents and businesses will have in taking steps to become more resilient. Participation and adoption of key initiatives are indicators of a community’s movement towards resilience, but the community also needs to identify short- and long-term actions to ensure that they are making progress in building resilience.