and (2) pays insufficient attention to the critical problem of effective communication with risk managers and the public. The opinion of the committee, however, is that these deficiencies are not unique to ecological risk assessment. Differences in the functions of different regulatory agencies clearly influence the types of data and inference guidelines used in health risk assessments, and effective risk communication is as important (and often as inadequately performed) in health as in ecological risk assessment.

DEFINITION OF FRAMEWORK COMPONENTS FOR ECOLOGICAL RISK ASSESSMENT

Hazard identification is redefined to be the determination of whether a particular hazardous agent is associated with health or ecological effects that are of sufficient importance to warrant further scientific study or immediate management action.

This change in definition is intended to account for the influence of regulatory mandates and other policy considerations on the conduct of risk assessments. Examples of such influences are restrictions on data acquisition or response time (e.g., premanufacture notification assessments under the Toxic Substances Control Act), standardized data requirements and regulatory criteria (pesticide registration under the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act), and the scoping provisions of the National Environmental Policy Act. Other aspects of hazard identification, such as investigation of cause-effect relationships and preliminary screening, would remain essentially unchanged.

Exposure-response assessment is defined as the determination of the relation between the magnitude of exposure and the probability of occurrence of the effects in question. Replacement of the term "dose" with a more general term is required, because "dose" has a distinctly medical connotation and cannot be effectively applied to nonchemical stresses, such as habitat change or harvesting. The "responses" addressed in ecological risk assessments include direct effects of exposure and the much broader indirect effects, such as secondary poisoning of raptors due to accumulation of pesticide residues in their prey and effects of harvesting on fish-community structure.

Exposure assessment is defined as the determination of the extent of

exposure to the hazardous agent in question before or after application of regulatory controls. In the committee's view, the term "exposure" can legitimately be applied to nonchemical stresses, including physical stresses (such as habitat and UV radiation) and biological stresses (such as species introductions). The committee considered changes in terminology on the grounds that the term "exposure" is too closely associated with chemical risks. However, the alternative terms discussed (e.g., stress and stressor) were unsuitable because of conflicts with medical uses of the same or similar terms.

Risk characterization is defined as the description of the nature and often the magnitude of risk, including attendant uncertainty, expressed in terms that are comprehensible to decision-makers and the public. Extension of the definition provided in the 1983 report is needed to permit more explicit discussion of uncertainty, to facilitate expression of risks in management-relevant terms (including valuation), and to emphasize the importance of communication between scientists and managers. The committee believes that improved communication is as important for health risk assessment as it is for ecological risk assessment.

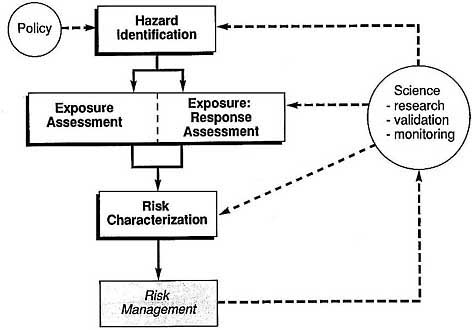

The revised framework is summarized in Figure 3-2. The relationships among the four components are unchanged from the Red Book: hazard identification is the initial step in an assessment. Exposure assessment and exposure-response assessment occur roughly in parallel and must be closely linked. The arrangement of those components in Figure 3-2, within a single box divided in half by a "permeable membrane," is intended to emphasize the ties between them. Risk characterization synthesizes the results of technical analyses and expresses them in a form suitable for valuation studies or other policy analyses that are carried out as part of risk management.

In addition to the four basic components, Figure 3-2 depicts two aspects of risk assessment that the committee wants to emphasize. As previously noted, it is essential to recognize that management considerations (e.g., regulatory constraints on the scope or time available for an assessment or legally prescribed definitions of acceptable or unacceptable uses) can shape the hazard identification step. The committee would also like to emphasize the need to create a connection between the results of today's risk assessments and the science base for future risk assessments. The risk assessment process should not end when a regulatory decision is made. Followup in the form of monitoring (where