5

Alternative Data Sources and Collection Methods

As noted throughout this report, the data collection system for U.S. international capital transactions has relied heavily on manual reporting by large financial intermediaries located in the United States, with an emphasis on banking activities. However, liberalization of world capital markets, securitization of transactions, emergence of new financial products, the rise in nonbank participants in markets, and increased use of offshore financial centers have given rise to numerous transactions beyond the reach of the traditional system. Data gaps are most severe for international transactions of U.S. nonbanks, U.S. residents' direct sales and purchases of foreign securities overseas, and cross-border derivatives transactions. At the same time, data filers have noted the burden of having to complete numerous forms whose purposes they do not fully understand. Data compilers, for their part, have had to contend with outdated collection methods and demands to collect information on increasing volumes of transactions with limited resources.

Clearly, the existing system is under stress, and there is a need to develop alternative data collection methods to improve its efficiency and effectiveness. In view of the global nature of transactions and their rapid expansion, improvements over the medium term in the coverage and accuracy of data, without substantial increases in resources, lie in drawing on information from existing custodians of financial assets and from large-payment, clear-

ance, and settlement systems. Over the long-term, as rising numbers of multinational corporations and financial institutions commit large sums to develop in-house international information and communications systems to meet their operational needs, the possibility of collecting balance-of-payments data electronically increases, as has recently been analyzed by a task force of the Statistical Office of the European Community (EUROSTAT). This chapter explores the feasibility of gathering securities data from global custodians, payment and settlement organizations, and clearing houses in the medium term and from automated data exchange systems over the long-term.

DATA SOURCES

GLOBAL CUSTODIANS

Global custodians are institutions that manage the custody of financial assets in multiple markets for clients, most of which are institutional investors. Many global custodians are leading commercial and investment banks and large brokerage houses. Over the past decade, these financial institutions have invested heavily in automation. They use their automated data systems not only to meet their own operational needs, but also to offer various fee-earning services to other financial institutions and money managers. Global custody is one of these services. Actual physical custody of assets is usually maintained by foreign local subcustodians, who keep the assets in the country of origin. The main role of a global custodian is that of master record-keeper and reporter. Every client is provided a monthly or quarterly report detailing information on assets held, including value and transaction date. Information on the national residence of the client is also available. Global custodians therefore appear to have much of what is needed to compile data on the U.S. positions (holdings) of foreign securities and changes in those positions.

Economies of scale provided by information technology have given rise to a relatively small number of very large global custodians around the world. Some of these include Bankers Trust, Chase Manhattan, Citibank, Morgan Stanley, Salomon Brothers, and State Street Bank in the United States, as well as Barclays Bank in the United Kingdom. These global custodians could serve as prime sources of information on international portfolio invest-

ment positions and their changes; in addition, with such data the quality of transaction data would also be improved.1

Global custodians have highly automated record-keeping and reporting systems. It would appear, therefore, that they could retrieve the necessary information at relatively low costs. Although automated systems of global custodians vary, there is uniformity in information maintained because of the record-keeping requirements of the 1974 Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) pension fund laws and the requirements of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). 2

An advantage of developing this data collection method is that many custodians are now building large telecommunications and information networks. This bodes well for the future development of an automated data collection system (see the discussion on electronic data exchange, below). A drawback is that not all major U.S. investors use global custodians in the United States to manage the records of their financial assets; some rely on custodians in other countries. Thus, U.S. global custodians would not have coverage of all U.S. holdings of foreign securities. However, since major U.S. investors do have to report their holdings directly to the Treasury Department (with the assistance of their foreign global custodians), some of the data would be available.

FINANCIAL CLEARING HOUSES AND PAYMENT AND SETTLEMENT SYSTEMS

Payment, clearance, and settlement organizations are institutions that process financial transactions. These organizations settle trades (transactions) by delivering the asset and payment, or, in the case of financial derivatives, by satisfying the terms of the contract. Most of these organizations have highly automated record-keeping systems. Economies of scale made possible by advanced

telecommunications technology have led to a moderate number of large clearance and settlement organizations around the world that handle most of the transactions. Most countries have only one major clearance and settlement organization; in the United States, a small number of organizations provide clearance and settlement services for the various types of transactions.

Some of the U.S. organizations provide services to members at the ''retail" level, matching the orders of buyers and sellers, keeping track of accounts of clients, and settling the trades generally through major banking institutions. Others, the large-value payments systems, provide the "wholesale" settlement networks. There are 3 clearing houses and 3 depositories that serve the nation's stock exchanges and over-the-counter dealers; 9 that serve the 14 futures exchanges (such as the Commodity Clearing Corporation); and 1 that serves equity options markets (the Options Clearing Corporation) (U.S. Office of Technology Assessment, 1990:81). These organizations typically serve their clients at the retail level and interact with (settle with and obtain credit from) depository institutions or banks, which, in turn, have access to this country's two large-value payment and clearance networks: Fedwire and the Clearing House Interbank Payments Systems (CHIPS).3 Both Fedwire and CHIPS are on-line, real-time electronic payment systems. Fedwire is the wire transfer network of the Federal Reserve, which electronically transmits funds and Treasury securities (on a book-entry basis) among banking institutions. CHIPS is a private electronic payment system owned and operated by the New York Clearing House Association, whose members are 11 New York money-center banks.4 These systems have grown dramatically with the explosion of domestic and international financial activities. The feasibility of collecting data from Fedwire and CHIPS is discussed below.

Fedwire

According to the Federal Reserve, a depository institution can use Fedwire for access to its account at its local Federal Reserve

bank to transfer securities or funds to any other domestic depository institution that has an account with a Federal Reserve bank. Depository institutions include all domestic commercial banks, foreign banks with branches or agencies in the United States, trust companies, savings banks, savings and loans associations, and credit unions that are covered by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). These institutions can transfer cash and securities both for themselves and for their customers, which include correspondent banks, governments, corporations, institutional investors, and individuals.

The method by which depository institutions secure access to the Fedwire system generally depends on their volume of use. Institutions with large volumes of securities or fund transfers usually have a computer-to-computer link with their local Federal Reserve bank. Institutions with relatively low volumes are connected by telephone lines to their Federal Reserve banks through personal computer links that use the Federal Reserve software, known as Fedline. Institutions that use Fedwire infrequently can get access to Fedwire off-line, by telephone calls to personnel at the Federal Reserve banks (Federal Reserve Board of Governors, 1992:730-731).

A Fedwire fund transfer message identifies the sending and receiving institutions, the dollar amount of the transfer, and the beneficiary of the transfer (if the institutions itself is not the beneficiary). A securities transfer message identifies the sending and receiving institutions, describes the securities issue and amount of funds to be transferred, and records the actual payment (if the securities are delivered against payments). The computer verifies that the sending and the receiving institutions have the securities or funds in the designated accounts. When the processing is complete, both institutions receive acknowledgments.

CHIPS

CHIPS is the central clearing system in the United States for international transactions, handling more than 95 percent of all dollar payments moving between the United States and the rest of the world. In addition to the 11 members of the New York Clearing House Association, CHIPS users include many other commercial banks with headquarters in New York, more than 95 New York branches or agencies of foreign banks, and a number of other banking offices. Currently, about 140 financial institutions use

CHIPS. About two-thirds of all CHIPS participants are foreign banking institutions in the United States.

CHIPS payments executed during a day are irrevocable and made final through settlement at the end of the day. CHIPS settles its net balances each evening with the Federal Reserve Bank of New York (FRBNY). A CHIPS settlement account at FRBNY is funded by the settling participants in a net debit position and drawn down by the New York Clearing House Association to pay those participants in a net credit position. After completion of daily processing, records of transactions are sent to participants by CHIPS.

CHIPS transfers and settles in U.S. dollars for international and domestic business transactions. These transactions are conducted by banks for their customers and for their own accounts, supporting the various financial service and intermediary functions required by businesses and governments. CHIPS serves as the conduit for moving dollars between participant banks for a wide variety of transactions, including:

-

foreign and domestic trade services (letters of credit, collections, and reimbursements);

-

international loans (placements and interest disbursements);

-

syndicated loans (assembly, placement of funds, and interest);

-

foreign exchange sales and purchases (spot market, currency futures, interest and currency swaps);

-

Eurodollar placements;

-

sale of short-term funds;

-

funds movement and concentration; and

-

Eurosecurities settlement.

The operation of CHIPS is based on a structured record format that embodies fixed and variable data fields. It is highly conducive to computer automation at both originating and receiving banks. By taking advantage of this structure, many participants send payment messages between dissimilar systems without any manual intervention. CHIPS can accept, for example, identification numbers from SWIFT (Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications) and automatically cross-reference them to the CHIPS Universal Identification Numbers (UIN). SWIFT is a European-headquartered electronic payments system for international transactions; it is a cooperative company created under Belgian law.

According to a recent FRBNY study (Federal Reserve Bank of

New York, 1987-1988), CHIPS handles payments for almost all foreign exchange transactions. In contrast, Fedwire accounts for virtually all payments related to transactions for securities, purchases, redemptions, financing, and federal funds purchases and sales. Significant overlap between the two systems exists, however, in the categories of payments related to bank loans, commercial and miscellaneous transactions, settlements, and Eurodollar placements.

Three categories of information that can be gleaned from both systems:

-

transactors: brokers/dealers, investor customers, security issuers, own accounts, own trading accounts, own investment accounts;

-

kind of investments: commercial paper, bankers' acceptances, domestic certificates of deposit (CDs), book-entry securities (Fedwire), Euro CDs, mortgage-back securities, municipal securities, and other or unspecified; and

-

nature of transactions: secondary markets, new issues, payments at maturity, and unspecified. In addition, four other categories of information are sometimes available:

-

purpose of transaction: investment, trading, repurchase agreement, safekeeping, other or unspecified;

-

numbers of transactions and dollar amounts of each item: investment, trading, repurchase agreement, safekeeping, other or unspecified;

-

originating place of transactions: outside or inside the United States; and

-

transactions for foreign customers and for banks' own foreign offices.

Clearly, not all the data that would be needed to record international capital transactions for balance-of-payments purposes are currently available from Fedwire and CHIPS. The information in the payment and clearance networks is purposefully kept to a minimum to lower clearing and settlement costs. In some cases, not all of the information currently being requested is available to the sending and receiving institutions or supplied by them, and not all of the information requested is needed to execute the transfers.

Nonetheless, it is technologically feasible for the systems to add information, as illustrated by the SWIFT payment system, which allows 100 additional characters to be included for each transaction, either in numerical or alphabetical form. There are also optional fields available in both the Fedwire and CHIPS networks.5 Of course, to require a private electronic clearance system to obtain and provide new information would probably require new legislation and, possibly, compensation. According to the Federal Reserve staff, the development of such new data formats would require a lead time of 2-3 years at a minimum.

Large-value payment systems are integral parts of the monetary institutions in a country. They are also key mechanisms in the operations of the global financial system. As such, their safety and soundness are crucial to national and international financial stability. Currently, industrial countries are working toward a set of common practices and standards to improve clearing and settlement of global trading of securities and multilateral banking transactions.6 Uniform codes of operation and system design to be developed for these financial information networks, under these private and public initiatives, will facilitate the introduction of electronic data interchange as a method of data collection in the future (see below).

RECOMMENDATIONS

-

The potential for using global custodians as a new source of data appears promising. In addition to information on securities holdings, the Treasury Department and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York should actively explore the feasibility of gathering flow data on securities transactions from global custodians and assess its cost-effectiveness. (5-1)

-

On the basis of the information currently available on Fedwire and CHIPS, it appears that it would be possible to secure statistical data on U.S. international capital transactions from the two systems. The Treasury Department and the Bureau of Economic Analysis should conduct a rigorous study to explore such feasibility by undertaking an in-depth analysis of a sample of transactions that pass through Fedwire and CHIPS. They should also determine whether cost savings would result from using data from Fedwire and CHIPS. If data for analysis cannot be released by CHIPS or Fedwire to outsiders due to privacy concerns, the Treasury Department and BEA could request the staffs of Fedwire and CHIPS to devise ways of providing the data without violating individuals' privacy. (5-2)

COLLECTION METHODS

ELECTRONIC DATA INTERCHANGE

An important recent development in information technology with powerful implications for the automated collection of economic data has been the emergence of electronic data interchange (EDI). EDI refers to the electronic transfer of computer-processable business data among the computer systems of different organizations using an agreed standard to structure the data. EDI is especially useful for frequent substantive exchanges of routinized information. Under certain circumstances, through the use of standard formats, it can allow businesses to reduce the use of paper purchase orders, invoices, shipping forms, and technical specifications. EDI can improve data accuracy while reducing data entry, mailing, and paper handling costs. Indirect benefits also arise from modified business practices, including reduced inventory, better cash management, reduced order time, greater sales through improved customer satisfaction, and more accurate and timely information for decision support.

The data standard that is taking the lead in the EDI field is EDIFACT—which stands for EDI for administration, commerce, and trade. Developed by the United Nations, it has been adopted on an international level. More than 130 EDIFACT messages have been established for the purpose of preparing invoices, customs declarations, and the transfers of funds, among others. EDIFACT messages are increasingly used in Europe in various economic sectors (such as construction, the social and health fields, and national accounts). In addition to exporters and importers in mer-

chandise trade, the banking community is showing interest with pilot projects, both nationally and internationally. SWIFT uses the EDIFACT standard, and European business administrations increasingly communicate in EDIFACT terms.

In the United States, the Accredited Standards Committee X12 chartered by the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) has developed the X12 standard. Although EDIFACT and X12 are separately established, they are considered similar families of standards, and the ANSI-X12 committee has played a key role in the definition of the EDIFACT. The committee is also committed to the convergence of X12 with the EDIFACT standard.

Under the aegis of EUROSTAT, a task force since July 1991 has been exploring the feasibility of using EDIFACT messages for collecting data on balance of payments and international investment positions. The task force is led by experts from De Nederlandsche Bank (the Netherlands Central Bank). The anticipation that paper recording of individual transactions may cease, causing the existing transaction (ticket) data collection system used in continental Europe to break down (see Appendix A), has been a major driving force behind the European balance-of-payments compilers' interest in EDIFACT. The movement toward the creation of a single capital market in Europe has also provided an impetus toward harmonizing balance-of-payments data across member states of the European Community.

The rationale for this approach is that business organizations are the source of balance-of-payments data. If they increasingly use EDIFACT messages, it would seem efficient that these messages be used for reporting balance-of-payments data. It capitalizes on the development of EDIFACT messages for commercial purposes by requiring the commercial originators of such messages to send copies or extracts to the balance-of-payments compilers. In this way, the collection of data for the balance of payments should become, in principle, cheap, simple, and quick. For items of data needed for official but not commercial purposes, separate data would be collected: in principle, this can be achieved by including an extra field (or fields) on the commercial electronic messages for official purposes. The EUROSTAT task force is working on a system for implementing this approach and for exchanging aggregated data among official bodies using the same EDI techniques and the same EDIFACT standard. It would be possible, in theory, to collect data on all cross-border transactions as they occur.

Under this approach, data on balance-of-payments and interna-

tional investment positions would be filed with balance-of-payments data compilers using electronic messages. Messages could relate to transaction data or survey data as appropriate. For transaction data, messages would cover transactions reported by customers through a commercial bank or directly to the balance-of-payments compiler, as well as banks' own transactions and customer transactions reported by banks to the balance-of-payments compiler. Reporting by the balance-of-payments compiler to international statistical bodies can also be done in electronic format.

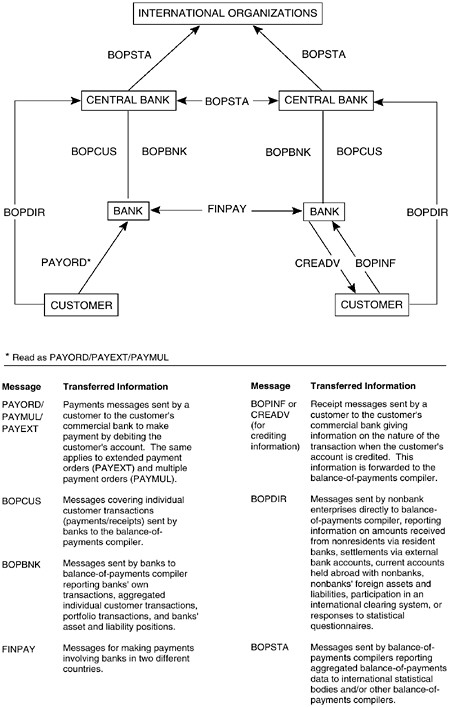

In researching the possibilities of using EDIFACT messages for reporting balance-of-payments data, the EUROSTAT task force developed a data flow analysis that traces the information exchanged between the various parties. A summary of the data flows identified by the task force is shown in Figure 5-1.

The balance-of-payments messages to be used fall in two categories: those that use existing, but slightly adjusted EDIFACT messages, and those for which new messages would be developed. The messages would cover all data collection systems and provide all information needed. The approach followed in developing messages would be flexible in that the use of all segments of the messages would be optional; however, national guidelines or regulations could make the use of all or part of these messages mandatory.

The compilation of balance-of-payments data requires the reporting of incoming and outgoing payments, that is, transactions between residents and nonresidents. The key, in most cases, is to allocate the transactions to the correct period, appropriate category, and geographic area. The principal data for balance-of-payments compilation in an electronic data system include:

-

identity of the resident engaged in the transaction [name and address, additional identification number, such as SIREN [in France], a VAT [value-added-tax] number, or other national registration number);

-

(industrial) activity of the resident engaged in the transaction;

-

country of the nonresident partner to the transaction;

-

date of the transaction;

-

total amount of the payment (possibly broken down, for instance, in the case of a composite payment on a loan, to interest and redemption payment);

-

currency of the transaction;

-

nature of the transaction, in code and in verbal description (about 200 kinds of balance-of-payments items are differentiated

-

according to regulations from EUROSTAT, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), and the International Monetary Fund (IMF); in some cases as, for example, that of outward direct investment, this might involve additional geographic data if the country of the payee differs from the country in which the direct investment took place, which is relevant for balance-of-payments data);

-

identity of the nonresident engaged in the transactions;

-

date of the message;

-

identification of the resident banking intermediary and of the banking intermediary of the nonresident; and

-

bank reference number.

The compilation of the data on international investment positions requires the reporting by residents of their stocks of foreign assets and liabilities, by value and function. The data needed include:

-

identity of the reporting resident;

-

debtor or creditor country;

-

value;

-

currency;

-

kind of stocks and flows;

-

date of the reported position;

-

type and sector of the reporting resident; and

-

identity of the nonresident.

A paperless process of reporting information to statistical authorities has potential benefits for both data compilers and data filers. The European compilers believe that automated reporting will be more timely and is likely to result in higher quality data. In addition, they expect that the switch from reporting by paper forms to reporting by electronic messages will bring about large cost savings because manual data transcription work, with possible typing errors, is significantly reduced. Increases in the accuracy and timeliness of data would also reduce follow-up costs. Banks, which act as intermediaries in collecting balance-of-payments data under an electronic reporting approach, can save costs by using EDIFACT messages. In the long run, the use of internationally exchanged EDIFACT balance-of-payments messages will save banks in a number of countries the costs of collecting forms to be used for reporting external transactions.

According to the EUROSTAT task force, savings also will ac-

crue to customers because they will in most cases no longer have to report the transactions to national compilers. This saving assumes that customers' resident banks will have all the necessary balance-of-payments information, which will be supplied by foreign payors in EDIFACT messages received through SWIFT or other international networks. Of course, this would require harmonized balance-of-payments data collection systems among countries and international networks, such as SWIFT, to transmit the messages.

An important aspect of this electronic approach is the development of standardized information codes and statistical systems for information extraction. It is important that national data compilers become involved in the development of the coding systems. It is crucial that the necessary information be coded so as to minimize retrieval costs. With regard to extraction systems, a crucial issue is the determination of how and when to aggregate information. This decision will affect costs because of the huge volume of information available. It will also bear on whether the anonymity of individual buyers and sellers can be maintained: in the absence of such anonymity, many buyers and sellers may be unwilling to reveal even their national origin. Confidentiality rules among nations will need to be set up for electronic data collection.

In the United States, the Bureau of the Census and the National Center for Education Statistics have laid the groundwork for using EDI to collect statistical data by developing transaction sets for economic and education information. Both approaches build on the standards established by ANSI. Under the proposed framework, these federal statistical agencies would be able to accept information based on different record-keeping systems (such as payroll, revenue, and cost data based on different definitions). Agencies could accommodate a variety of record-keeping formats used by individual businesses by translating the respondents' reports to agency standards. This approach is believed to have the potential to reduce reporting burden on both small and large businesses, increase response rates, and improve the quality of data collection (U.S. Office of Management and Budget, 1993).

To coordinate the U.S. work on EDI with international developments in this area, the U.S. Office of Management and Budget (OMB) has established liaison with the EUROSTAT task force. In addition, a working group of U.S. statistical agencies interested in EDI has been established to explore EDI capabilities in the private sector, develop plans for use of EDI to improve data collection

methods, and promote convergence of the national and international standards. Nonetheless, progress in this area is likely to take some time because of the complexity of harmonizing international standards, which entails commitment, resources, and consensus of market participants, regulators, and national governments.

INTERNATIONAL DATA EXCHANGE AND COORDINATION

Internationalization of financial markets has meant that data compilers can no longer rely solely on domestic data sources. Coordination and cooperation among countries to exchange data is needed to improve coverage of individual countries data. The IMF and the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) maintain extensive databases on international banking transactions that can be used to cross-check and improve national balance-of-payments data. The IMF/BIS databases are especially useful in improving information on transactions of domestic nonbank entities with banks abroad. As discussed in Chapter 3, BEA has recently increased utilization of data obtained by BIS from central banks, and it also exchanges data directly with authorities in other countries to improve the balance-of-payments data on portfolio transactions of nonbanks. BEA is reviewing the feasibility of further expanding the use of such data.

There are differences in definition and coverage among reporting systems of countries that submit banking data to the IMF and the BIS. Major differences exist in data reported by banks on their custody accounts, definitions of instruments (such as deposits and repurchase agreements), and geographic allocations. Placing these data on a basis consistent with U.S. concepts has required and will continue to require cooperative efforts of the IMF, BIS, central banks, and national statistical authorities.

RECOMMENDATIONS

-

In the United States, the Federal Reserve, the Treasury Department, and the Bureau of Economic Analysis should allocate resources to study the systems architecture of information technology adopted by financial institutions and multinational corporations and to investigate ways to facilitate the development of these automated data collection systems to prepare for the emerging electronic global trading environment. (5-3)

-

Data exchanges and the use of the databases of international

-

organizations require that the data of different countries be comparable in coverage, definitions, and concepts. Despite recent efforts of various countries to bring about greater convergence, significant conceptual differences and data inconsistencies among countries remain. This circumstance points to the need for careful and systematic comparisons of bilateral data, as well as for comparisons between national data and information contained in international databases, before substituting or making adjustments to national databases. This process is inevitably labor-intensive and time-consuming. One approach would be to focus on the countries of greatest quantitative importance and data that offer the most possibilities for improvement. Another promising approach is for U.S. statistical officials to consult closely with statistical experts in countries with which the United States is engaged in data exchanges. The aim would be to enhance understanding of how the bilateral statistical systems, definitions, and concepts can be modified to make the systems more consistent. (5-4)

-

An essential step toward harmonizing data on international transactions of various countries is to encourage national compilers to adhere to standards currently being developed by international organizations, such as the International Monetary Fund, the Bank for International Settlements, the United Nations, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, and other international securities and financial groups. In addition, different international organizations need to establish guidelines showing how their different databases can be reconciled. (5-5)

As national data compilers strive to adjust to the internationalization of capital transactions, the challenge is how to improve data collection systems to reflect several factors: the needs of data users; the growing number and diversity of institutional and private players engaging in international capital transactions; the changing role of intermediaries and financial instruments; the complexity of financial transactions; and the costs versus the benefits of collection. Only when this challenge is met will U.S. analysts, business people, and policy makers be in a position to adequately understand the impact of international financial activity on the U.S. economy and the role of U.S. financial institutions in the world economy.