3

Measurement Systems to Assess Individual- and Population-Level Change

Many data systems already exist that can be used to monitor changes in children’s health and well-being. Experience with these systems has revealed how innovations can improve health at the individual and population levels. Five presenters described examples of these systems and pointed toward how they could be replicated and expanded.

EVALUATING SUBSTANCE ABUSE PREVENTION ON A LARGE SCALE ACROSS STATE POPULATIONS

Robert Orwin, a senior study director in the Behavioral Health Group at Westat, led off the session by describing results from a national public health initiative to counter substance abuse: the Strategic Prevention Framework State Incentive Grant (SPF-SIG), an ongoing program of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Its goals are to prevent the onset of substance abuse problems and to reduce their progression; to reduce substance abuse-related problems and their consequences in communities, such as alcohol-related motor vehicle incidents; and to build capacity and infrastructure for prevention work at state and local levels. Orwin and his colleagues conducted an evaluation of the first two cohorts of SPF with funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse in partnership with SAMHSA (Orwin et al., 2014). The study, which linked state, community, and intervention factors with population changes relating to substance abuse, is a major advance because of its use of large-scale population data, he said.

The SPF model features an interative process involving:

- Assessment of assets and needs at the local and state levels;

- Building, assessing, and increasing capacity;

- Strategic planning driven by data analysis;

- Funding of communities to implement and carry out intervention programs at the local level based on the assessment, capacity building, and planning process;

- Ongoing evaluation throughout the process, resulting in additional assessment and capacity building; and

- Sustainability and cultural competence that are woven throughout all steps of the program.

The SPF program differs from previous federal prevention efforts in two novel ways that are related to the workshop theme, Orwin said. One is that the initiative requires using population-based information to set state priorities and justify how resources are allocated to communities. This approach, known as “data-driven planning,” had not yet been applied in a major way to substance abuse prevention at the time SPF began in 2004, he said. A second distinctive aspect is that SPF measures its effectiveness by relying on population-based outcomes, unlike the traditional approach of examining effects on individuals at the program level.

Twenty-four states and 2 territories participated in cohorts I and II of SPF, which funded 450 communities that initiated 2,534 interventions with goals such as reducing alcohol and marijuana use, underage drinking, binge drinking, and driving after drinking. Orwin summarized the results as generally being “very positive.” For example, out of 174 communities that targeted 30-day alcohol use, 132 showed improvement; 79 performed significantly better, while 15 did significantly worse. Similarly, efforts to reduce driving after drinking in high school students led to improvements in 56 out of 78 communities (Diana et al., 2014). Aggregating those community-level findings to look at statewide effects revealed even stronger outcomes, he said.

The time period of the analysis—around 2006 to 2012—coincided with a secular downward trend in substance abuse across the United States. However, some states in the SPF project collected data from communities that did not offer intervention programs, which allowed for a comparison against the nationwide shift. “Even when the secular trend was taken into account, the results were generally quite impressive over a large scale,” Orwin said. About two-thirds of the 450 communities and states targeting substance abuse improved relative to their comparison communities. Seven states that ran intervention programs reaching more than 50 percent of their populations achieved improvements relative to the national downward trend on most outcome measures (Diana et al., 2014).

The researchers examined which predictors at the state, community, and intervention levels might explain success in reducing substance abuse and its consequences. Generally, state-level factors relating to implementation, infrastructure development, and population were not all that predictive of the variations in outcome performance. “The communities were really where the action was,” he said, referring to community-level factors such as funding and organizational support, coalition capacity, SPF step scores, and intervention variables.

Communities that used their SPF grants to leverage additional prevention funding from other sources were more likely to achieve significant reductions in substance abuse measures. However, the results depended on the sources of that extra money. Block grants and community or municipal funds appeared to predict significant favorable changes in outcomes, whereas financing from foundations, corporations, or private donors did not. With few exceptions, factors relating to organizational support, such as state-provided technical assistance, had no effect on the variations in outcomes.

Community partners that were well-structured coalitions with good processes in place, paid leadership, membership diversity, and supportive communities achieved greater reductions in underage drinking outcomes. As far as intervention variables, an interesting question was which kinds of prevention strategies can promote population-level changes. Whereas traditional programming approaches try to change individuals’ behaviors, currently there is a major emphasis on so-called environmental strategies for health prevention, such as large-scale education campaigns and community-level actions such as changing zoning laws for liquor stores. The researchers found that the number of environmental strategies that a community implemented predicted more reductions in substance abuse outcomes. Tailoring interventions to the needs of the target population also predicted decreases in underage drinking outcomes (Diana et al., 2014).

The take-home messages from SPF are that researchers should do more evaluations with population data, do it better, and explain the results more simply, Orwin said. Protecting and expanding the data systems are also important goals, he added.

CLOSING RESEARCH DATA GAPS TO PREVENT YOUTH SUICIDES

According to the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), as of 2012, suicide accounted for 40,600 deaths in the United States—and 5,178 were young people from 10 to 24 years old, making it the second leading cause of death in that age group. For the past 3 years, Jane Pearson, associate director for preventive interventions in the Division of Services and Intervention Research at the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)

and chair of the NIMH Suicide Research Consortium, has been working on a prioritized research agenda for suicide prevention, a project being implemented by a task force of the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention (NAASP). Experts have been looking at youth suicide numbers for decades, Pearson told the workshop audience, and “It was time to try to do something about it.”

The task force set out to prioritize research objectives that, if implemented, could reduce all suicides — including youth suicides — by 20 percent in 5 years (NAASP, 2014). While the task force of course understands how long it takes to do research, it wanted to push to “find something that looked tractable, something that we should be able to do.” The task force identified several gaps in research data around key questions: What causes suicide? How does one detect risk? What are adequate interventions? What kinds of prevention could work?

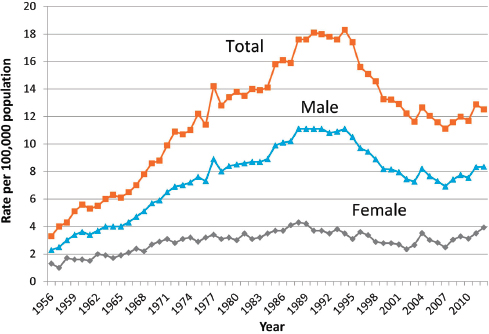

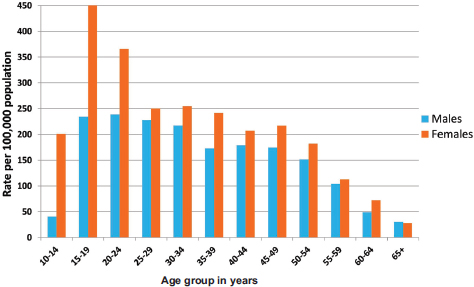

Pearson walked through several examples of data that are currently available. She started with the 2012 youth suicide numbers from NCHS, which were the most recent data available at the time of the workshop (see Figure 3-1). The suicide statistics are available online (and via downloadable app) through the CDC’s Web-Based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS).1 WISQARS makes it possible to examine data at the state level and filter by gender, age, race, and ethnicity. The system also includes information on injury morbidity, which includes the numbers of suicide attempts as captured by a survey of hospital emergency departments (see Figure 3-2). Another source of suicide data is the recently expanded National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS), which offers an opportunity for state health departments to put together rich data around a death, such as linking to police or hospital records that may indicate stressors in an individual’s life.

Looking at a graph of suicide statistics for the U.S. population, Pearson pointed out that there were upticks in the numbers in 2008 and 2009, perhaps reflecting the effects of the recession. What is disturbing is that the numbers for 2012 continue to show an uptick. “This is troublesome,” she said. For 15- to 19-year-olds in particular, suicide rates declined in the early 2000s but have shown an uptick since then.

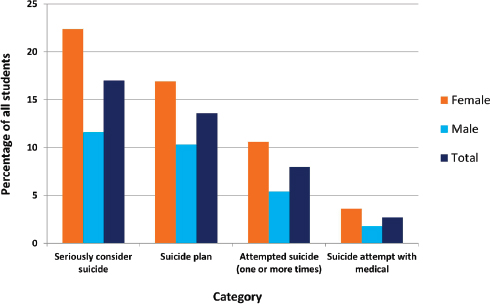

In the teenage and young adult years (ages 10 to 24), many more females attempt suicide than males do, but then that discrepancy evens out over time. Remarkably, Youth Risk Behavior surveys show that as many as 20 percent of youths seriously consider suicide. “What does that mean?” Pearson asked. “We just don’t have a good sense of why there are some kids who think about it and nothing happens, and some kids think about it and do something.” Experts talk about suicide in terms of a continuum

__________________

1 Available at www.cdc.gov/ncipc/wisqars/default.htm (accessed March 25, 2015).

FIGURE 3-1 Suicide rates among persons aged 15 to 19 years. Suicide in the United States has risen slightly in recent years after a substantial decline.

SOURCE: CDC vital statistics; courtesy of Alex Crosby.

FIGURE 3-2 Emergency department self-inflicted injuries by age and sex. Data are shown for 2012 in the United States.

SOURCE: CDC WISQARS, 2012; courtesy of Alex Crosby.

FIGURE 3-3 Suicidal ideation and behavior among high school students.

NOTE: Data from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) 2013, for the 12 months preceding the survey.

SOURCE: CDC Youth Risk Behavior Survey: http://www.cdc.gov/HealthyYouth/yrbs/index.htm (accessed March 25, 2015); courtesy of Alex Crosby.

that starts with people thinking about killing themselves, then planning an act, and attempting it (see Figure 3-3), but more longitudinal and phenomenological data are needed to understand those attempts, she said.

What can be done to reach youth at risk for suicide? The emergency room is a promising place for intervention.2 A recently launched program called Emergency Department Screen for Teens at Risk for Suicide (ED-STARS)—funded by NIMH—is studying high-risk youth who receive care at 14 participating emergency departments.3 Researchers will develop innovative new approaches for predicting suicide attempts, including a computerized adaptive screening tool similar to one created for identifying depression, and an implicit association task that has been adapted to screen for suicidal thinking (Cha et al., 2010; Gibbons et al., 2013).

The justice system is another route for addressing youth suicides. In

________________

2 For details, visit http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nedsoverview.jsp (accessed March 25, 2015).

3 For more information, see http://www.nimh.nih.gov/news/science-news/2014/personalizedscreen-to-id-suicidal-teens-in-14-ers.shtml (accessed March 25, 2015).

Utah, a 2002 study found that 63 percent of youths who died by suicide had had run-ins with the juvenile justice system (Gray et al., 2002). In a subsequent pilot program, University of Utah researchers screened youths going through the juvenile court system and found high rates of mental illness. Providing preventative interventions for the juvenile offenders improved their mental health and reduced new offenses (Moskos et al., 2007). Funding for that project was dropped, but the Utah researchers then applied for money from the Garrett Lee Smith (GLS) grants administered by SAMHSA.

The GLS grants support programs that train gatekeepers such as teachers and juvenile justice personnel on how to help a young person who is suicidal. A 2013 SAMHSA report to Congress found that in counties that implemented GLS training programs, the suicide rate went down in 10- to 24-year-olds, with 237 deaths prevented between 2007 and 2010 (SAMHSA, 2013). “It gives us hope that some of these programs that SAMHSA is implementing are making a difference,” Pearson said.

An important issue for prevention is measuring suicidal youth’s help seeking and getting them to the right kind of assistance. Studies indicate that “suicidal youth have pretty bad approaches to their own coping and getting help,” she said. They are more likely to reach out to their peers than adults (Gould et al., 2004; Pisani et al., 2012). “You have a lot of kids who get told about somebody who is suicidal, but they are asked to keep it a secret: Don’t tell anybody. This is a big issue.”

The National Science Foundation (NSF) and National Institutes of Health (NIH) have started funding research to explore how social media might be used to help youths with mental health issues such as substance abuse or depression. For example, a recent NSF-funded study of an online social network for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) youth suggested that users with fewer social connections were at greater risk for depression (Homan et al., 2014).

HOW DATA REPOSITORIES ARE OPENING ACCESS TO RESEARCH DATA ON AUTISM AND MENTAL HEALTH ILLNESSES

Greg Farber, director of NIMH’s Office of Technology Development and Coordination, described an innovative infrastructure, called the NIMH Data Archives, that collects information about research on human subjects. The infrastructure started with the National Database for Autism Research (NDAR), which Farber’s office oversees, and which recently expanded to include all data supported by NIMH from clinical trials as well as data related to the Research Domain Criteria initiative. In addition, NDAR has developed a “deep federation” in linking with other data repositories ranging from the Autism Tissue Program to the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative. “Qualified researchers can access

the data,” he said. “You can launch a query from the NIMH website”—or from several other sites—“and cover all of these other data repositories simultaneously.”

NDAR was originally created in late 2006 as a joint initiative of the NIMH, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. “Putting data into a repository is like filling a pool with a garden hose. It takes a while before you have enough data to be interesting. At this point, the pool is pretty full. We have data from over 77,000 subjects. We are holding around 500 terabytes, a variety of different types of data.”

Two principal building blocks shape how the data are organized: data dictionaries (which define the language characterizing research on autism and other illnesses) and the global unique identifier (GUID). The NDAR data dictionary provides a flexible and extensible framework for data definition by the research community and makes more than 500 instruments freely available for download from ndar.nih.gov. As data aggregates in the federal repositories, the community can begin to compare various data dictionaries and “start to pick winners,” Farber said.

Another benefit of aggregating data is that if a researcher tries to send in an answer that falls outside the value range defined by a particular data dictionary, “We send it back and say, ‘No, that is not quite right.’” At first, researchers hate being told their data are incorrect, he said, but they appreciate discovering errors sooner rather than later, and fix them. “The quality of data across the field is improved.” The data repositories’ query tool also allows investigators to quickly perform quality control checks on their data by comparing their results to the large samples of data in the repository.

Meanwhile, the GUID (rhymes with fluid) is a key building block designed to avoid including within the data repositories any information—such as Social Security numbers—that could personally identify individual study subjects. Using the GUID software, any researcher can enter information from a person’s birth certificate (such as first name, last name, date, and place of birth) to generate a unique identifier number for that individual. If the same information is entered by other researchers in different laboratories, the same GUID number will be generated.

The GUID thus allows data from multiple research labs to be aggregated on the same research participants without having to share personally identifiable information about them. “This is a useful tool that we are happy to make available to a wide array of research communities,” Farber said.4

The querying systems on the NDAR website let investigators easily

________________

4 For a video about informed consent issues, see http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tb6euCVoous (accessed March 25, 2015).

search the data repositories in various ways: by laboratory sources, by published scientific papers (linked to citations in PubMed), by data dictionary definitions, or by research concepts. Being able to access the shared datasets can enable real science. By running queries, scientists also can observe that many research participants are seen in many different laboratories, which was surprising, Farber said. Researchers usually assume “that we are drawing from a random sample when, in fact, we are drawing from a much smaller sample. That has real possibilities for biasing the sorts of results that we are getting.”

How much is NDAR being used so far? “One question about these databases always is, if you build it, do they really come?” Farber said. But “Once [the pool] is full, people really do come.” More than 270 users have been granted access to NDAR, and Farber’s office has started seeing papers published based on data that came from the data registry (Richman et al., 2013; Sansone et al., 2012; Supekar et al., 2013). All in all, NDAR has made autism data useful and accessible, said Farber, and his office is happy to work with researchers on taking in data they have collected and making the information accessible and searchable through the NIMH Data Repositories.

USING DATA TO INFORM DECISION MAKING IN MARYLAND PUBLIC SCHOOLS

Catherine Bradshaw, professor and associate dean for research and faculty development at the University of Virginia’s Curry School of Education, next presented a glimpse of how end-users are using datasets in real-world practice within the school setting. She described two federal initiatives in education: the Maryland Safe and Supportive Schools (MDS3) project and the Race to the Top. They offer examples of how data are being collected on children’s academic performance and behavioral and mental health and applied to decisions about individual children or the adoption of evidence-based practices.

This work is in collaboration with the Maryland State Department of Education and is guided by a conceptual framework for prevention that builds upon multitiered systems of support. Maryland follows a well-known noncurricular, schoolwide tiered prevention model called Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS), which focuses on improving systems and practices through data-based decision making (Sugai and Horner, 2006).5 The PBIS model applies a public health approach, wherein it is generally understood that about 80 percent of children will respond to universal interventions, while 20 percent need additional services. As the

________________

5 For more details, see http://www.pbis.org (accessed March 25, 2015).

magnitude of a problem rises, the level of intensity of support, resources, and data collection needed to address it increases as well.

Many schools do a good job in getting a universal level of supports into place, such as implementing schoolwide behavior management strategies, Bradshaw said. But when schools find that a student is not responding to that universal program and they want to understand why and which kinds of services might help, data-based decision making is necessary. Response to intervention is a data-based decision making framework used in education to guide that program selection process.

MDS3 is a collaboration among Johns Hopkins University, the Maryland State Department of Education, and Sheppard Pratt Health System, a large nonprofit mental health provider. Funded with $13.7 million from the U.S. Department of Education and around $1 million from the William T. Grant Foundation, MDS3 has three broad aims. One is to improve the school environment by cutting down on violence, bullying, and substance use and by improving connections among youth. The second is to develop a sustainable Web-based survey system for assessing school climate to guide the decision-making process. The third is implementing a continuum of evidence-based programs or practices to meet students’ needs. In a pilot project, 58 schools implemented the school climate assessment system, and then half of the schools were randomized to a condition in which they selected from a menu of evidence-based programs. The model was tested as part of a 4-year randomized controlled trial. “We were very interested in how to improve the school climate in these school settings,” Bradshaw said. Schools in the group that received interventions adopted the PBIS model and also chose to implement evidence-based programs such as Botvin’s Life Skills Program for substance abuse prevention, or Check-In/Check-Out to boost student engagement and attendance. Schools received training and coaching by an implementation support provider, referred to as a school climate specialist. The overall framework for helping schools select and implement evidence-based programs is akin to the Communities That Care community-wide implementation model.

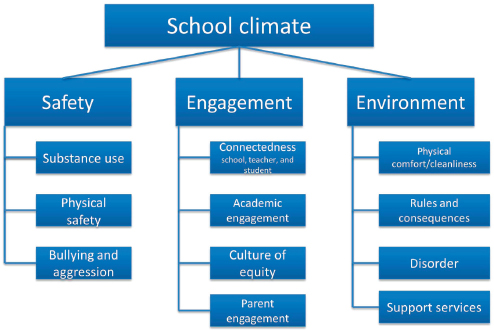

The MDS3 project uses the U.S. Department of Education’s model of school climate, which outlines the three key areas of safety, engagement, and environment (see Figure 3-4). Many experts on school climate focus on students’ perceptions of the school environment, but Bradshaw and her colleagues also wanted to examine behavioral issues, such as bullying or substance abuse, which can influence—or be influenced by—those perceptions.

The trial is currently in its final year of data collection, which includes gathering data on fidelity of implementation; observations of the school environment; and measures of school climate assessed via a Web-based surveillance system, called the MDS3 School Climate Survey, that allows students, parents, and school staff to complete a voluntary, anonymous

FIGURE 3-4 The U.S. Department of Education’s School Climate Model. The model considers safety, engagement, and the school climate.

SOURCE: Adapted from Bradshaw et al., 2014b.

online questionnaire (Bradshaw et al., 2014a). School administrators can access the survey data in real time and instantly generate status reports through the password-protected website. The MDS3 initiative has expanded into middle and elementary schools, and more than 200 Maryland schools are now participating. Preliminary results from the randomized trial indicate significant improvements in several behavioral outcomes and aspects of school climate (Bradshaw et al., 2014a).

Meanwhile, Bradshaw and her colleagues worked with the Maryland State Department of Education to develop a data dashboard for Maryland’s participation in the Race to the Top initiative. Goals included identifying which of 19 different indicators or risk factors could predict key outcomes, such as whether students graduated from or dropped out of high school, and whether students progressed to fifth or eighth grades on time or were held back. The researchers analyzed state data on three cohorts—each with more than 60,000 students—across elementary, middle, and high school. The 19 indicators included measures such as proficiency on standardized tests, yearly retention data, and yearly absences; demographic or racial information were not included in the initial analysis because the state did not want the resulting algorithm to be driven largely by demographic-based risk factors.

The data dashboard made it easy to visually stratify each student cohort into categories by the number of risk factors they had, and to see what the “cutpoints” were for the different outcomes. For instance, a high school student with zero risk factors is likely to graduate, but a teen with three or more risk factors is not. Faced with such a high-risk student, a school principal might respond by saying, “We have got to get to this kid and start thinking about ways that we can support [him or her],” Bradshaw said. The researchers found their model fit best for predicting the outcome of whether students did not graduate; academic achievement and retention were the best predictors (Pas and Bradshaw, 2014).

Wrapping up, Bradshaw highlighted several common themes from the two data-based initiatives in Maryland schools: The focus and framing of the data dashboard varies by user need, which may include different interests in school climate, dropout rates, particular types of data (e.g., academic performance or behavior), or decision making at the school level versus for individual cases. Predictive modeling can be helpful for guiding decision making. Incentives for data collection and use are important. Lastly, it is important to provide training and a framework for using that information to support decision making.

MEASURING POPULATION-LEVEL PROGRESS IN THE FIGHT FOR DRUG-FREE COMMUNITIES

In the last presentation of the panel, Kareemah Abdullah, director of the National Community Anti-Drug Coalition Institute and vice president of training operations at Community Anti-Drug Coalitions of America (CADCA), shared a perspective on measurement systems that assess population-level change through the context of coalitions. Based in Alexandria, Virginia, the nonprofit CADCA supports data-driven strategic planning and prevention of illicit drug use, underage drinking, and youth tobacco use for coalitions across the United States and its territories.6 CADCA represents more than 5,000 community coalitions and affiliates nationwide and has helped build coalitions in 29 countries. Its goal is to unite these partners in bringing about population-level reductions in substance abuse rates.

The National Coalition Institute is the arm of CADCA that provides high-level training and technical assistance, evaluation and research, and capacity building for coalitions that receive funding through the Drug Free Communities (DFC) Support Act passed by Congress in 2001. The institute is charged with “making coalitions smarter faster,” Abdullah said. CADCA’s Community Problem-Solving Model aims to help coalitions achieve population-level change. Realizing programs are necessary but not

________________

6 For more information, see http://www.cadca.org (accessed March 25, 2015).

sufficient, coalitions focus on environmental strategies to achieve significant youth behavioral outcomes.

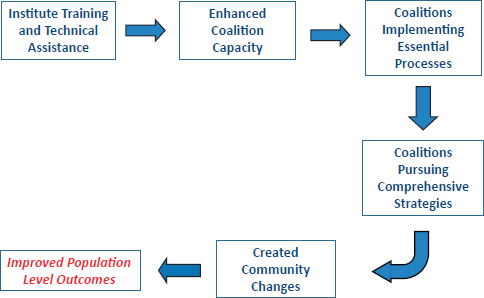

Its research shows that “one of the most important indicators for achieving population-level outcomes is engaging in essential processes and having the capacity to do so.” The institute operates from a conceptual “framework for community change” in which training and technical assistance trigger coalitions to improve their capacity, which in turn enables them to implement essential processes that lead to a set of comprehensive intervention strategies (see Figure 3-5). Such strategies create community change that resonates at the population level, driving population-level improvements. This is the model that CADCA uses in providing the training that all DFC-funded coalitions are required to undertake.

CADCA has found that communities need a problem-solving process to be able to ask critical questions and identify the “local conditions” and risk factors for which interventions can be developed to reduce problem behaviors. “We are identifying the problem. We are then asking why that problem exists, what are the causal factors about the problem behavior among youth in your particular neighborhood. . . . Then, your comprehensive intervention strategies must be mapped, measured, and monitored at that local condition level.” One example of a local condition is when youths are gaining access to alcohol because neighborhood merchants are not carding them.

FIGURE 3-5 Framework for community change of the National Coalition Institute.

SOURCE: Abdullah, 2014.

CADCA focuses on seven strategies for behavioral change: providing information, enhancing skills, providing support, enhancing access or reducing barriers, changing consequences or incentives, changing physical design, and modifying or changing policies. The last four areas target changes in environment and are necessary for achieving the greatest improvements in youth behavioral outcomes, Abdullah explained. All seven strategies must be applied to each local condition that is fueling a substance abuse problem.

CADCA’s Institute has been independently evaluated since its inception in 2002. An independent evaluation led by Pennie Foster-Fishman of Michigan State University examined the impacts of CADCA’s institute training and technical assistance.7 This longitudinal 4-year analysis tracked coalitions that had received DFC funding in 2008–2009. Overall, the percentage of coalitions that engaged in creating policy changes grew significantly in the 3 years following their CADCA training. Policy change was a major indicator for positive outcomes in youth behaviors, Abdullah said.

However, the analysis also revealed that the increase in policy-changing work dropped off at 4 years’ posttraining (Foster-Fishman, 2014), indicating that coalitions “at this stage needed additional training and technical assistance,” she said. Many coalitions needed to revisit their collective work and begin to focus on new local conditions because, in many cases, their strategies for addressing previously identified local conditions had succeeded.

Another evaluation conducted by ICF International studied the extent to which pursuit of CADCA’s problem-solving approach had an impact on youth substance abuse. In a cross-site analysis of middle school and high school students, this study measured how many of the teens reported perceptions of parental disapproval of alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco use and perceptions of risk associated with substance use; and how many had used substances in the past month. Communities with DFC-funded coalitions that engaged in the problem-solving approach showed better outcomes in youth behaviors than did communities without DFC coalitions (DFC National Evaluation, 2013).

Overall, of all the elements in the CADCA’s framework for change, the amount of “community change”—that is, program and policy changes—that coalitions produce has the strongest impact on population outcomes. Given the complex, messy nature of communities and coalition work, Abdullah recommended that measurement systems for assessing coalitions’ effect on youth behavioral outcomes have three components: They should be simple, with a linear logic model. They should be able to capture varied

________________

7 For more information, see http://www.cadca.org/resources/detail/coalitions-trained-cadcainstitute-are-more-effective-community-problem-solvers (accessed March 25, 2015).

interactions and outcomes, she added, because “dynamics need to be considered where multiple coordinated pathways are part of the outcomes and very complex.” Lastly, they should look at complexity-based theories for both action and change, Abdullah said.

DFC coalitions have a real impact through their work in communities, she concluded, because the prevalence of substance abuse among young people increases or decreases based on their perceptions of harm and use.

Abdullah, K. 2014. Measurement systems to assess individual- and population-level change. Presented at Institute of Medicine and National Research Council Workshop on Innovations in Design and Utilization of Measurement Systems to Promote Children’s Cognitive, Affective, and Behavioral Health, Washington, DC.

Bradshaw, C. P., K. J. Debnam, S. Lindstrom Johnson, E. Pas, P. Hershfeldt, A. Alexander, S. Barrett, and P. J. Leaf. 2014a. Maryland’s evolving system of social, emotional, and behavioral interventions in public schools: The Maryland Safe and Supportive Schools Project. Adolescent Psychiatry 4(3):194-206.

Bradshaw, C. P., T. E. Waasdorp, K. J. Debnam, and S. L. Johnson. 2014b. Measuring school climate in high schools: A focus on safety, engagement, and the environment. Journal of School Health 84(9):593-604.

Cha, C. B., S. Najmi, J. M. Park, C. T. Finn, and M. K. Nock. 2010. Attentional bias toward suicide-related stimuli predicts suicidal behavior. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 119(3):616-622.

Diana, A., R. G. Orwin, and J. Park. 2014 (February). Outcomes from the SPF SIG cross-site evaluation, Cohorts I and II. Presented at the Community Anti-Drug Coalitions of America Annual Meeting, National Harbor, MD.

Drug-Free Communities Support Program 2012 National Evaluation Report. 2013 (June). Fairfax, VA: ICF International. http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/dfc_2012_interim_report_annual_report_-_final.pdf (accessed March 25, 2015).

Foster-Fishman, P., and Y. Mei. 2014 (September 15). Longitudinal evaluation of the impact of CADCA’s institute’s training and TA on coalition effectiveness. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University. http://www.cadca.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/institute/lastestfindingsinstituteeval.pdf (accessed March 25, 2015).

Gibbons, R. D., G. Hooker, M. D. Finkelman, D. J. Weiss, P. A. Pilkonis, E. Frank, T. Moore, and D. J. Kupfer. 2013. The computerized adaptive diagnostic test for major depressive disorder (CAD-MDD): A screening tool for depression. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 74(7):669-674.

Gould, M. S., D. Velting, M. Kleinman, C. Lucas, J. G. Thomas, and M. Chung. 2004. Teenagers’ attitudes about coping strategies and help-seeking behavior for suicidality. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 43(9):1124-1133.

Gray, D., J. Achilles, T. Keller, D. Tate, L. Haggard, R. Rolfs, C. Cazier, J. Workman, and W. M. McMahon. 2002. Utah youth suicide study, phase I: Government agency contact before death. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 41(4):427-434.

Homan, C. M., N. Lu, X. Tu, M. C. Lytle, and V. M. B. Silenzio. 2014. Social structure and depression in TrevorSpace. Proceedings of the 17th ACM Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing. February 15, 2014. Baltimore, MD.

Moskos, M. A., S. R. Halbern, S. Adler S, H. Kim, and D. Gray. 2007. Utah Youth Suicide Study: Evidence-based suicide prevention for juvenile offenders. Journal of Law and Family Studies 10:127-145.

NAASP (National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention Research Prioritization Task Force). 2014. A prioritized research agenda for suicide prevention: An action plan to save lives. Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health.

Orwin, R. G., A. Stein-Seroussi, J. M. Edwards, A. L. Landy, and R. L. Flewelling. 2014. Effects of the Strategic Prevention Framework State Incentives Grant (SPF-SIG) on state prevention infrastructure in 26 states. Journal of Primary Prevention 35(3):163-180.

Pas, E., and C. Bradshaw. 2014. Student Risk Trends Dashboard Project. A report prepared for the Maryland State Department of Education, Baltimore, MD.

Pisani, A. R., K. Schmeelk-Cone, D. Gunzler, M. Petrova, D. B. Goldston, X. Tu, and P. A. Wyman. 2012. Associations between suicidal high school students’ help-seeking and their attitudes and perceptions of social environment. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 41(10):1312-1324.

Richman, D. M., L. Barnard-Brak, A. Bosch, S. Thompson, L. Grubb, and L. Abby. 2013. Predictors of self-injurious behaviour exhibited by individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities Research 57(5):429-439.

SAMHSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration). 2013. Report to Congress: Garrett Lee Smith Youth Suicide Prevention Program. Rockville, MD: SAMHSA.

Sansone, S. M., K. F. Widaman, S. S. Hall, A. L. Reiss, A. Lightbody, W. E. Kaufmann, E. Berry-Kravis, A. Lachiewicz, E. C. Brown, and D. Hessl. 2012. Psychometric study of the Aberrant Behavior Checklist in Fragile X Syndrome and implications for targeted treatment. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 42(7):1377-1392.

Sugai, G., and R. H. Horner. 2006. A promising approach for expanding and sustaining school-wide positive behavior support. School Psychology Review 35:245-259.

Supekar, K., L. Q. Uddin, A. Khouzam, J. Phillips, W. D. Gaillard, L. E. Kenworthy, B. E. Yerys, C. J. Vaidya, and V. Menon. 2013. Brain hyperconnectivity in children with autism and its links to social deficits. Cellular Reproduction 5(3):738-747.