4

Using Quality Measures to Facilitate System Change

Whether developed purely for research or to be applied in program improvement, measures have the potential to fundamentally change social service systems, including child care, juvenile justice, education, and health care. However, these changes are almost invariably complex and can have harmful as well as beneficial effects. Four speakers at the workshop examined the systemic changes that can occur as the result of the development and implementation of new measures and drew lessons on how to optimize the effects of such changes.

ENSURING HIGH QUALITY IN MEASURES OF CHILD CARE AND PRESCHOOL: A CAUTIONARY TALE

Quality rating and improvement systems, which link child care subsidy levels to quality ratings, emerged in the late 1990s and now operate in about three-quarters of the states (Child Trends, 2014). More recently, the Race to the Top Early Learning Challenge encouraged states to integrate quality-monitoring systems across funding streams, and the Improving Head Start for School Readiness Act of 2007 required lower-quality Head Start grantees to recompete for funding (though none were actually required to do so until 2011).1 These policy initiatives have accelerated a trend of adopting measures designed for other purposes for high-stakes

________________

1 Additional information can be found at the Federal Register 75, no. 183 [September 22, 2010]: 57717, and at http://www2.ed.gov/programs/racetothetop-earlylearningchallenge/index.html (accessed March 25, 2015).

uses, noted Rachel Gordon, professor in the Department of Sociology and associate director of the Institute of Government and Public Affairs at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

These initiatives also have directed attention to the use of measures that are valid and reliable. For example, the Race to the Top Early Learning Challenge required states to use “valid and reliable” indicators of the overall quality of the early learning environment and of the quality of adult–child interactions.2 Such use of the terms reliable and valid suggest that these are static properties of a measure for all time, all purposes, and all populations, Gordon observed, but noting “This isn’t consistent with our contemporary thinking about measurement.” Instead, the developers and users of measures need to consider the intents of each research and policy use and weigh the body of reliability and validity evidence against each use, she said, which is consistent with the latest Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing (AERA/APA/NCME, 2014). For instance, the body of evidence desired to demonstrate reliability and validity for program self-assessment may be different than that for teacher professional development, and both of these could differ for policy decision making and accountability. Similarly, the developers and users of measures need to build in continuous and local validation of measures selected for various uses and allow for the refinement of measures over time and place, Gordon said.

She used two examples to talk about these issues in greater detail. The first is the Early Childhood Environment Rating Scale (ECERS),3 and the second is the Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS).4 These are intensive observational measures where independent observers spend at least several hours in classrooms. Together, they are used in about 90 percent of states (Child Trends, 2014).

As the high stakes use of quality rating and improvement systems came into being, states aimed to assure that publicly funded programs were of high quality and to incentivize advancement. In response to a question, Gordon pointed out that at first it was hard to get child care centers to participate voluntarily. Some states then moved to include all centers in the program and started them out at the bottom level, after which they could move up in the rankings. “The rating and improvement is meant to partly be marketing” for the centers, she said, but “it is meant to also give information to consumers about making choices.”

__________________

2 Race to the Top Early Learning Challenge requirements can be found at https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2011/08/26/2011-21756/applications-for-new-awards-race-to-thetop-early-learning-challenge (accessed March 25, 2015).

3 Additional information on ECERS can be found at http://ers.fpg.unc.edu/early-childhoodenvironment-rating-scale-ecers-r (accessed March 25, 2015).

4 Additional information on CLASS can be found at http://teachstone.com/the-class-system (accessed March 25, 2015).

Earlier interpretations concluded that a strong association existed between these quality measures and student readiness outcomes. However, this evidence often focused on statistical significance and not the size of associations, did not rigorously adjust for selection (confounds), and may have reflected measures of quality levels typical several decades ago, prior to contemporary licensing and programmatic standards, Gordon noted. The emerging consensus is that the associations with readiness are not always significant and are generally small—typically 0.1 or smaller in effect size (Abner et al., 2013; Burchinal et al., 2011; Gordon et al., 2013; Keys et al., 2013).

How these measures were designed may relate to their limitations for high-stakes uses, Gordon explained. The ECERS-R emerged in the 1970s from a checklist to help child care practitioners improve the quality of their settings. It reflects developmentally appropriate practices, including a predominance of child-initiated activities selected from a wide array of options and a “whole child” approach that integrates physical, emotional, social, and cognitive components. The ECERS-R has more than 400 indicators across 43 items, grouped in a way that makes sense in the context of practice. These features of the measure may be valid from a philosophical perspective, Gordon said, but they do not necessarily focus on the kinds of intentional teaching that increasing evidence indicates is best for school readiness.

The CLASS was developed more recently based on research suggesting that interactions between students and adults are the primary mechanism of student development and learning (Pianta et al., 2008). Its predecessor was part of a research study, and it was later aimed at professional development and coaching before being adopted in high-stakes policy contexts. It has a very different structure than ECERS-R, because it requires observers to assimilate what they see in order to assign scores to just a few items in the categories of emotional support, classroom organization, and instructional support.

In a high-stakes context, a measure should provide very high agreement if it is being used for specific cutoffs, Gordon noted. However, a recent publication from the CLASS developers reveals that inter-rater reliability is low (Cash et al., 2012). The CLASS developers also recently found a bi-factor structure (Hamre et al., 2014), with one general dimension (responsive teaching) and two specific dimensions (proactive management and routines, and cognitive facilitation). These differ from the subscales written into policy, and domains may align differently than originally thought with aspects of quality specific to readiness for school. CLASS scores also tend to cluster in just a few scale categories, and this limited variation may make it difficult to reveal changes in quality over time and may attenuate associations between quality measures and cognitive outcomes. Because public investments

expect high-quality preschool promoting academic school readiness, these results could have the unintended consequence of discouraging investments in early child care, Gordon said.

The bottom line is that information about reliability and validity needs to be independently collected, Gordon concluded. For example, she briefly mentioned a pilot study at the University of Illinois known as the Early Investments Initiative that uses new technology to take a careful look at variation in quality within and across the school day and across quality definitions, measures, and standards. She also pointed out that technology can be leveraged to gather evidence, both for greater understanding and for feedback for teachers and parents. A major objective is to provide continuous feedback and learn from teachers about the reliability and validity of measures, Gordon said. “Quality is the right goal, but we want to be sure we have the tools aligned with our current high-stakes policy use.”

THE JUVENILE JUSTICE REFORM AND REINVESTMENT INITIATIVE

The Juvenile Justice Reform and Reinvestment Initiative (JJRRI) is a comprehensive approach to reforming the juvenile justice system using a research-based, data-driven, decision-making platform to inform system improvements and service delivery. The ultimate goal of the initiative, said Kristen Kracke, a social science specialist at the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, is to improve both outcomes and cost effectiveness.

Research in juvenile justice has demonstrated that early intervention is less expensive and more effective than involvement with the juvenile justice system. It also has shown that, for youth involved in the juvenile justice system, interventions focusing on control (such as detention) are less effective than therapeutic approaches for reducing recidivism, and that the deeper youth go into the system, the more likely they are to reoffend (Lipsey, 2009; Lipsey and Cullen, 2007; Loughran et al., 2009).

JJRRI,5 which is an innovation pilot funded by the Office of Management and Budget, involves three jurisdictions over a 3-year project period. Its short-term goals are improved program delivery, better matching of youth to services, system improvements, and reinvestment of cost savings to the front end of youth services in the community rather than in confinement. Its long-term goals are decreased recidivism rates and improved outcomes for youth, improved cost effectiveness of juvenile justice services, and a reduction in public cost and reinvestment in community services.

__________________

5 For more information on JJRRI, see http://www.ojjdp.gov/grants/solicitations/FY2012/JJRRI.pdf (accessed March 25, 2015).

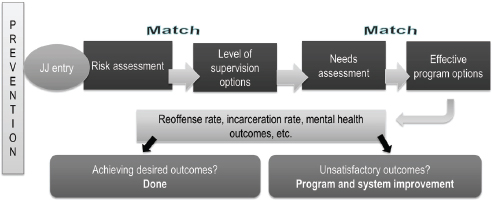

A major objective of the initiative is to create an evidence-based operating platform, which would increase the match between the risk assessment and supervision levels, and between needs assessments and program options (see Figure 4-1). Implementation of the platform has involved the installation of a program rating instrument known as the Standardized Program Evaluation Protocol (SPEP). Developed by Mark Lipsey at Vanderbilt University’s Peabody Research Institute based on a meta-analysis of more than 600 intervention studies, SPEP assesses how well current program practice matches the profile of programs with research evidence for effectiveness. Pilot programs are working with SPEP to derive an initial set of scores, which guide the program improvement process, and a second set of scores designed to reveal changes in program quality.

SPEP covers four key areas:

- Program or service type

- Quality of service delivery

- Amount of service, including duration and intensity of contact (face-to-face, group, etc.)

- Risk level of youth served

It is a holistic process, Kracke emphasized, designed to align all parts of the system, including risk and needs assessments, service selection, ongoing case management, and reinvestment in front-end outcome-driven community-based services. “It is a continuous improvement process for all of the partners involved—the courts, the agencies, the providers, and the youth themselves.”

FIGURE 4-1 Matching risks in an evidence-based operating platform for juvenile justice (JJ). An evidence-based operating platform for JJ matches risk to supervision and needs to effective programs.

SOURCE: Kracke, 2014.

As an example of how the alignment process works, Kracke described in greater detail a part of the system known as the dispositional matrix. The dispositional matrix is a structured decision-making tool for courts on dispositions for youth that matches risk levels and offense types to recommend a supervision level. In Florida’s implementation of the matrix, for example, low-risk offenders remain in the community with minimal supervision, moderate-risk offenders are placed in more structured community programs with intensive probation for higher risk youth, and residential placement is reserved for the highest risk offenders after community-based alternatives have been exhausted. The underlying principle is to place youth in an optimal placement while trying to meet the youth’s needs in the most cost-effective way.

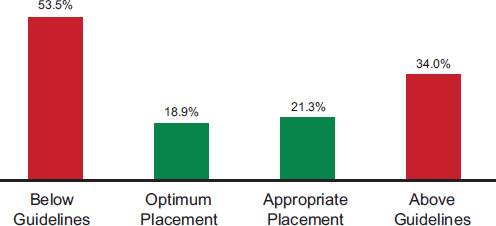

In Florida, when youth are placed in the least restrictive environment, their 12-month recidivism is lower than for placements that are either below or above the guidelines (see Figure 4-2) (Baglivio and Mark, 2014). These are “really powerful data,” said Kracke. The information also makes it possible to monitor the results of differential placement by jurisdictions while not taking away judicial discretion. “If a jurisdiction or a district is making discretionary decisions always above the guidelines or always below the guidelines, this gives them the data to show them the direct impact of that—and the state knows.”

“It is very exciting work,” Kracke concluded. “We think it is one of the next best things in terms of helping us meet our mission, which is to have the juvenile justice system be rare, fair, and beneficial.” Evidence-

FIGURE 4-2 All youth 12-month recidivism by matrix adherence level. Optimum placement in the least restrictive environment reduces recidivism.

SOURCE: Kracke, 2014, from Baglivio and Russell, 2014.

based practice takes money and time to cultivate, she noted. But evidence developed in one area also can have applications across the social sciences.

CAN CHILD MENTAL HEALTH CROSS THE QUALITY CHASM?

As with the educational system and juvenile justice system, the health care system is in the process of building an infrastructure of structural measures with associated process and outcome measures. In particular, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) contains a large number of provisions focused on quality measurement and accountability, observed Harold Pincus, professor and vice-chair of the Department of Psychiatry and codirector of the Irving Institute for Clinical and Translational Research at Columbia University, and also director of quality and outcomes research at New York-Presbyterian Hospital. To take just one example, within the area of mental health care, the value-based inpatient psychiatry quality reporting program is a pay-for-reporting, rather than a pay-for-performance system, that is having an impact on the mental health care provided by hospitals, Pincus said.

Part of the concern with quality in the health care system dates to the Institute of Medicine (IOM) reports To Err Is Human (IOM, 1999) and Crossing the Quality Chasm (IOM, 2001). The latter report established six domains of quality health care:

- Safe—Avoids injuries of care

- Effective—Provides care based on scientific knowledge and avoids services not likely to help

- Patient-centered—Respects and responds to patient preferences, needs, and values

- Timely—Reduces waits and sometimes harmful delays for those receiving and giving care

- Efficient—Avoids waste, including waste of equipment, supplies, ideas, and energy

- Equitable—Care does not vary in quality due to personal characteristics (gender, ethnicity, geographic location, or socioeconomic status)

A subsequent IOM report, Improving the Quality of Health Care for Mental and Substance-Use Conditions, looked specifically at the quality chasm for mental health and substance abuse, including care for children (IOM, 2005). The report identified a series of obstacles for mental health and substance abuse conditions, including obstacles to patient-centered care, poor linkages across the health care system, and an insufficient workforce capacity for quality improvement.

Pincus directed his attention to another obstacle—a weak measurement and improvement infrastructure—and cited the following six conclusions from the report:

- Clinical assessment and treatment practices are not well standardized and classified for use with administrative datasets. Data about the kinds of care being provided, the kind of conditions being treated, and outcomes are not readily available.

- Outcomes measurement is not widely applied despite the availability of reliable and valid instruments and the demonstrated value of measurement-based care (Harding et al., 2011).

- Not enough attention has been given to the development or implementation of performance measures for mental health and substance abuse care, especially for children.

- Quality improvement measures have not yet permeated the day-today operations of mental health services.

- The workforce is not trained in quality measures and improvement. 6. Policies have not effectively incentivized quality and efficiency.

In addition, Pincus pointed out that with the profusion of new measures being developed, the number particular to the mental health of children is small in proportion to the need. Efforts on behalf of children therefore are needed to develop reliable, valid, and feasible quality measures.

The ACA requires the establishment of a National Quality Strategy to implement better measurement and improvement of quality, and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) also has a number of quality programs for hospitals, physicians, payers, and health care settings. Pincus called attention to several key features of these quality measurement systems.

First, measures can improve performance by teaching people how to improve. Furthermore, this can be done across domains of safety, effectiveness, equity, efficiency, patient-centeredness, and timeliness.

Measurements also can be used for accountability. Such measurements require a higher threshold, said Pincus, when they are used for such purposes as public reporting and payment.

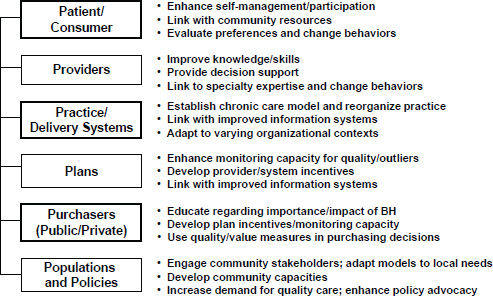

Measures can be used across the different silos of the health care system, including mental health, and at multiple levels. For example, Pincus outlined a “six P” conceptual framework at the level of patients, providers, practices or delivery systems, health plans, public and private purchasers, and populations and policies (see Figure 4-3). These levels can be analyzed in terms of five types of measures:

FIGURE 4-3 The “six P” conceptual framework. NOTE: BH = behavioral health.

SOURCE: Pincus, 2014.

- Structure—Are adequate personnel, training, facilities, security, quality improvement infrastructure, information technology resources, and policies available for providing care?

- Process—Are evidence-based processes of care accessible? Are they delivered with fidelity?

- Outcome—Does care improve clinical outcomes?

- Patient experience—What do users and other stakeholders think about the system’s structure, the care they have received, and their outcomes?

- Resource use—What resources are expended for the structure, processes of care, and outcomes?

Developing indicators in turn involves a series of steps:

- Establishing an evidence base

- Translating evidence to guidelines

- Translating guidelines to measure concepts

- Operationalizing concepts to measure specifications (which includes determining a numerator and denominator)

- Testing for reliability, validity, feasibility

- Aligning measures across multiple programs

- Stewardship, including updating measures over time

The data for quality measures can come from multiple sources, including administrative data, chart reviews, electronic health records, registries, and patient surveys. In addition, benchmarks need to be set, said Pincus. “What rate is right? If you are looking at adherence to certain types of medications, should everybody be 100 percent adherent to all their medications? Or are there some elements of patient preference, adverse effects and other kinds of issues that need to be taken into account?”

Multiple players are involved in the measurement process, including evidence developers (such as researchers, the National Institutes of Health [NIH], and Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute [PCORI]), guideline developers (such as professional associations), measure developers and stewards (such as the National Committee for Quality Assurance [NCQA] and CMS), measure endorsers (such as the National Quality Forum [NQF]), measure selectors and advisers (such as NQF, Measures Applications Partnership [MAP], and CMS), and measure users, including CMS, health plans, organizations, the media, and the public. Pincus focused on the endorsement criteria of the NQF, which include the following sets of standardized criteria6:

- Importance of measure—Extent to which the specific measure focus is evidence-based, important to making significant gains in health care quality, and improving health outcomes for a specific high-priority (high-impact) aspect of health care where there is variation in or overall less-than-optimal performance

- Scientific acceptability—Extent to which the measure, as specified, produces consistent (reliable) and credible (valid) results about the quality of care when implemented

- Usability—Extent to which potential audiences are using or could use performance results for both accountability and performance improvement to achieve the goal of high-quality, efficient health care for individuals or populations

- Feasibility—Extent to which the required data are readily available or could be captured without undue burden and can be implemented for performance evaluation

Finally, Pincus noted that indicators can be used to improve quality at the clinical level, the organizational level, and the policy level. Measurement needs to be built into the processes of care, he said, because successful interventions require that people be followed over time and that outcomes be

________________

6 Additional information about the NQF criteria for evaluation of measures can be found at http://www.qualityforum.org/docs/measure_evaluation_criteria.aspx (accessed March 25, 2015).

measured. For example, an accreditation process could incorporate within it an expectation of longitudinal measurement, which gets reported as a measure of outcomes. But a key question remains—accountability. “You have a lot of players,” Pincus noted, and then asked “How do you hold them accountable? What sort of shared accountability is necessary and how can it be operationalized?” Some innovations supported by the ACA, such as accountable care organizations, can specify accountability, but these provisions may not be operationalized in a way that has an impact on care for children.

QUALITY MEASURES AND IMPROVEMENT IN HEALTH CARE

As part of its accreditation process for health plans, NCQA looks at performance-based measures of health care quality. For example, a measure it has been using in recent years is the percentage of children who receive appropriate follow-up care when they are prescribed medications for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). “It is not very impressive performance,” said Sarah Scholle, vice president of research and analysis for NCQA, noting that only about 45 percent of children get appropriate follow-ups. Similarly, the number of people who receive a follow-up within 30 days of being hospitalized for a mental illness is worryingly low—only about 55 percent to 75 percent for different kinds of health plans, despite the seriousness of mental health hospitalization.

Having a quality measure does not necessarily focus attention on improvement in the area, Scholle pointed out. “Just because you have a quality measure, it doesn’t mean that it is going to galvanize the kind of attention, even when there is some accountability attached to it.”

In a recent review of behavioral health quality measures, NCQA found 496 such measures, though many are variations on a much smaller number of themes. But only 12 percent of these measures are nationally endorsed, and only 10 percent focus on children and adolescents. Most of the measures used data that can be captured from claims data, because it is much easier to capture that information than it is to derive data from medical records.

A good quality measure needs to be reliable and valid for the particular use of that measure, said Scholle, and it needs a good evidence base. The evidence is the foundation for a measure’s development, along with a review of the environment, guidelines, and important concepts surrounding that measure. Draft measure specifications need to be tested with feedback from the people who are going to be measured and the people who are going to use the measure.

As an example of this process, Scholle described the work that has been done to improve a measure for adolescent depression.7 First, the measure developers articulated a vision of what high-quality care for adolescent depression would look like. A screening process would lead to a good assessment to determine a diagnosis. Depending on the severity of illness, a patient might undergo brief supportive counseling or different kinds of treatment. Ideally, symptoms and functionality would be followed and assessed over time as they either respond to treatment or go into remission.

Using an existing measure in adults that is based on a patient health questionnaire, the group developed measures for monitoring, remission, and treatment adjustment for patients aged 12 to 17. Preliminary data indicate that a major challenge with the measure was the low rates of symptom monitoring for depressed adolescents, with 83 percent of a sample of 684 adolescents not being followed up 4 to 8 months after a diagnosis of major depression. Among those who were followed up, 5 percent of the total sample were in remission 4 to 8 months later, 4 percent had responded without remission, and 8 percent did not respond. Among those who were not followed up, many may have gotten better, but “you have to go out and find those kids and make sure they are okay,” said Scholle.

The logic model for quality measurement starts with structure, said Scholle, including training and ongoing supervision in evidence-based therapy, an infrastructure for collection of patient-reported data, and systems for sharing information across care teams (Lewandowski et al., 2013). It then progresses through various processes, including access to and use of behavioral health services, receipt of evidence-based therapy, and monitoring of symptoms and functioning using standardized tools. Outcomes include fewer harmful events, diminished symptoms, improved functioning, and school attendance.

According to this logic model, important issues for evidence-based therapies are which therapies to use, which populations to target, criteria for determining whether the evidence-based treatment is carried out, the data sources for capturing treatment, and access to confidential records.

This work on depression is following a model being used by other federal agencies to develop outcome measures for adults, both in the general medical sector and in behavioral health, Scholle stated. Key questions are whether tools are available, which tools to use or develop, methods for data collection, the expectations for improvement over time, and accountability. “For every measure, we would have to think about ‘what do you expect?’” said Scholle. “Who is accountable? Is it the individual clinician?

________________

7 This project was supported by grant number U18HS020503 (PI: Scholle) from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).

Is it the practice? Is it the delivery system? Is it the health plan?” Often, the responsibility belongs to the system as a whole, not just to the clinician or the patient, Scholle said. For example, a clinician may provide the care while a care coordinator makes sure that a patient returns for a scheduled appointment.

Scholle also pointed out, in response to a comment about the difficulties posed by electronic health record systems for clinicians, that much work needs to be done to make such systems more usable, both for clinicians and the care team in clinical care as well as for quality measurement. In part, a major challenge is rethinking who should be doing what within that system. For example, some pieces of the documentation can be done by other members of the care team. In addition, the model of the electronic health record is now based on paper records rather than thinking about the system as an electronic interface that includes clinical decision support and an interface to families and patients.

The ACA is changing the incentives for primary care providers and health care institutions. It is helping to create joint accountability through models like shared savings programs, health homes, patient-centered medical homes, and incentives for states and health plans, so improving mental health and substance use outcomes becomes a community responsibility. However, existing quality measures for mental health and substance use show only limited improvement, and measures assessing psychosocial interventions are lacking. Efforts to develop outcome measures for children and adolescents are under way but face challenges. New efforts to develop quality measures should focus on demonstrating how measures can inform clinical care and provide opportunities to monitor meaningful aspects of quality, Scholle concluded.

Abner, K., R. A. Gordon, K. Kaestner, and S. Korenman. 2013. Does domain-specific quality of child care mediate associations between the type of care and child development. Journal of Marriage and Family 75:1203-1217.

AERA (American Educational Research Association)/APA (American Psychological Association)/NCME (National Council on Measurement in Education). 2014. Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing. Washington, DC: AERA. http://www.apa.org/science/programs/testing/standards.aspx (accessed March 25, 2015).

Baglivio, M., and R. Mark. 2014. The Florida Department of Juvenile Justice Dispositional Matrix: A Validation Study. Bureau of Research and Planning, Florida Department of Juvenile Justice. February 2014. http://www.djj.state.fl.us/docs/research2/the-fdjjdisposition-matrix-validation-study.pdf?sfvrsn=0 (accessed March 25, 2015).

Burchinal, M., K. Kainz, and Y. Cai. 2011. How well do our measures of quality predict child outcomes? A meta-analysis and coordinated analysis of data from large-scale studies of early childhood settings. In Quality Measurement in Early Childhood Settings, edited by M. Zaslow, I. Martinez-Beck, K. Tout, and T. Halle. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing.

Cash, A. H., B. K. Hamre, R. C. Pianta, and S. S. Myers. 2012. Rater calibration when observational assessment occurs at large scale: Degree of calibration and characteristics of raters associated with calibration. Early Childhood Research Quarterly 27:529-542.

Child Trends. 2014. QRIS compendium. http://qriscompendium.org (accessed March 25, 2015).

Gordon, R. A., K. Fujimoto, R. Kaestner, S. Korenman, and K. Abner. 2013. An assessment of the validity of the ECERS-R with implications for assessments of child care quality and its relation to child development. Developmental Psychology 49:146-160.

Hamre, B., B. Hatfield, R. Pianta, and F. Jamil. 2014. Evidence for general and domain-specific elements of teacher-child interactions: Associations with preschool children’s development. Child Development 85:1257-1274.

Harding, K. J., A. J. Rush, M. Arbuckle, M. H. Trivedi, and H. A. Pincus. 2011. Measurement-based care in psychiatric practice: A policy framework for implementation. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 72(8):1136-1143.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 1999. To err is human: Building a safer health system. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2001. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2005. Improving the quality of health care for mental and substance-use conditions. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Keys, T. D., G. Farkas, M. R. Burchinal, G. J. Duncan, D. L. Vandell, W. Li, E. A. Ruzek, and C. Howes. 2013. Preschool center quality and school readiness: Quality effects and variation by demographic and child characteristics. Child Development 84(4):1171-1190.

Kracke, K. 2014. Juvenile Justice Reform and Reinvestment Initiative (JJRRI). Presented at Institute of Medicine and National Research Council Workshop on Innovations in Design and Utilization of Measurement Systems to Promote Children’s Cognitive, Affective, and Behavioral Health, Washington, DC.

Lewandowski, R. E., M. C. Acri, K. E. Hoagwood, M. Olfson, G. Clarke, W. Gardner, S. H. Scholle, S. Byron, K. Kelleher, H. A. Pincus, S. Frank, and S. M. Horwitz. 2013. Evidence for the management of adolescent depression. Pediatrics 32(4):e996-e1009.

Lipsey, M. W. 2009. The primary factors that characterize effective interventions with juvenile offenders: A meta-analytic overview. Victims and Offenders 4:124-147.

Lipsey, M. W., and F. T. Cullen. 2007. The effectiveness of correctional rehabilitation: A review of systematic reviews. Annual Review of Law and Social Science 3:297-320.

Loughran, T. A., E. P. Mulvey, C. A. Schubert, J. Fagan, A. R. Piquero, and S. H. Losoya. 2009. Estimating a dose-response relationship between length of stay and future recidivism in serious juvenile offenders. Criminology 47(3):699-740.

Pianta, R. C., K. M. La Paro, and B. K. Hamre. 2008. Classroom assessment scoring system manual, PreK. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing.

Pincus, H. 2014. Can child mental health cross the quality chasm? Children’s behavioral health, healthcare reform, and the “quality measurement industrial complex.” Presented at Institute of Medicine and National Research Council Workshop on Innovations in Design and Utilization of Measurement Systems to Promote Children’s Cognitive, Affective, and Behavioral Health, Washington, DC.