3

Toward Personal Health: Going Home and Beyond

Eric Dishman

Intel

Dishman described his long association with the problems of the provision of health care in the patient’s home and home-based primary care and the ways in which Silicon Valley–style technologies can help from his perspective as general manager of Intel’s Health Strategy & Solutions Group. Despite the accomplishments with which others credit him, Dishman began by talking about what he termed his failures. “I’ve spent 30 years trying to take health care home and have mostly failed at doing so, because it hasn’t scaled yet.” These capabilities—from care models to payment models and technologies—have not become widely available to enough people.

Misdiagnosed with a rare form of kidney cancer at age 19 years, Dishman spent the next 23 years being told he would die within 1 year (until a correct diagnosis and a subsequent successful kidney transplant in 2012) and sitting in cancer clinics and dialysis clinics with people who were mostly in their 70s and 80s. As a result, he developed an interest in aging. He had the youthful “tenacity and ferocity” to try to “change the barriers that were making the experience of illness worse than it needed to be.” Professionally, he began on this path studying nursing homes and two decades ago attempted a telehealth start-up for chronic care. Now he is involved in research and development at the corporate level, running a global health and life sciences business.

Three years before his cancer was diagnosed, Dishman became personally familiar with the panic that family caregivers feel when his grand-

mother, who had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, nearly burned his grandparents’ house down. He used his early-days computer to try to create an alert system (“an intelligent sensor network with remote connectivity”) that would trigger when his grandmother went into the kitchen and turned on the oven in the middle of the night. Although this early experiment in the development of a technology to help seniors live independently actually failed, he said, “That was the hook. I took the bait at that moment and have never let it go.” There have to be ways to change care models and use technologies to help with the exact problems that Karen Marshall mentioned (see Chapter 1, Box 1-3), he said, “and that I was experiencing back then.”

His first experience with chemotherapy taught him more about asserting “consumer control.” He was given a dose that was too high, and it was physically devastating. Thereafter, in 21 more rounds, he insisted that the chemotherapy be low dose, given over long periods of time, and delivered at home as much as possible.

One difficulty that Dishman has encountered is that neither paper records nor the emerging electronic health records of today include a field for patient goals. He taught his providers to use the file nickname field to insert a few words about the goals he wanted his care organized around: snow and exercise. This was to remind them that when they developed his evolving treatment plan, they were not to aim for longevity but for preserving his opportunities to ski and get exercise.

Dishman was adamant about maintaining control because over the long course of his illness he nearly died three times, each time because of system-related problems and not the cancer per se. First was the “too-much-at-once” initial chemotherapy, second was a hospital-borne infection, and third was overmedication from a care team whose members “weren’t keeping track of each other.” It took determination to get care provided in the way in which he wanted. As recently as 8 years ago he was told, “We can only do home care for people age 65 and above. That’s all we’re set up for.”

The next-to-last round of chemotherapy took place at home, by self-infusion, and cost one-tenth of what a center-based procedure would have, Dishman said. He learned to operate remote patient-monitoring technologies. Yet, he says the system—from the hospital to the oncologist to the payers—fought him every step of the way. He told them, “You have the studies now, thanks to the [Institute of Medicine] and others, that show hospitals are dangerous places. I’m incredibly immune compromised, and you’re insisting I continue to make the pilgrimage to the medical mainframe to do this?”

These two seeds—independent living technologies for seniors and patient-centered goals, both of which are focused on doing as much care as possible at home for as long as possible—have grown and intertwined.

In Asia, where Dishman has recently been working intensively, the need to invent home-based care models is a necessity because of the demographics of the population and other challenges. For example, Intel is helping Japanese communities that were devastated by the Fukushima earthquake and tsunami recover. Their former centralized health care services and clinical records system was destroyed. As they rebuild, Dishman said, they are working toward a home- and community-based care model that is not centralizing its capacity, technologies, and documentation.

In China, the scale of the population and the concomitant challenges can be hard to imagine. By 2020 or 2025, China will spend more than the United States on health care, Dishman said, even though they are spending far less per capita than the United States. One of the challenges in dealing with the aging population in China is the one-child family. “They now have an average couple trying to take care of four, sometimes eight people, if the great grandparents are alive.” Despite a centuries-long cultural tradition of filial piety and ancestor worship, the Chinese government in 2013 joined some other countries in adopting a law saying that people had to take care of their aging parents’ financial and spiritual needs.

China’s growing elderly population, combined with its extreme economic challenges, “is driving some really innovative things,” Dishman said. For about a decade, Intel staff have been thinking about old-age-friendly cities and the technology infrastructure that would enable such cities. A policy challenge that the Chinese face, as do many countries, is the separation of the medical care and social care sectors. The sectors need to combine their resources with private family funds to enable a team to decide in a comprehensive, flexible way what an individual or family needs most. This is in contrast to payment systems that require funds to be used in specific ways.

Analysis of the numbers of doctors and nurses in China, especially ones trained in geriatric care, stacked up against the growing need indicates such a sizable gap that it is clear that the country cannot rely on a physician- and nurse-driven model. “Most of these people will never even come close to a physician or nurse in their lifetimes,” Dishman said. The country will need to adopt a community health worker–driven model that can also enlist family members and neighbors “in some pretty intensive ways.” China’s second big challenge is how to finance long-term care services and supports, he said. They do not have any program akin to Social Security, for example.

Intel brought in experts from around the world to demonstrate different community-based care models, focusing on the quality of the result and not the payment model or technologies employed. That exercise built Dishman’s appreciation for the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs home-

based primary care program and convinced him that “the future of care is team based, collaborative, holistic, and in the community.” According to Dishman, China is now trying to develop a strategy focused on creating a community care workforce, infrastructure, and business model. In truth, such a model can serve people of all ages, so the argument for it can be based on universal design principles, he said. The model that the Chinese are trying to build is a “care-flow services network” that will allow many different agencies and companies—government service providers, benefit providers, medical service providers, or family—to use a common infrastructure to deliver care in the community and, at the same time, allow substantial innovation in the applications used and services provided. They are trying to go to scale—especially to economic scale—with such a model.

The Chinese are already building smart platforms based on activities of everyday life—railway use, communications, shopping, and phones and other devices—and want to build platforms to provide services of daily living, like housing, laundry, and food, plus health management and medical services, Dishman said. They are not thinking about health care in isolation, as often happens in the United States, assuming that “everything else” is somehow taken care of. They have in mind a whole social engagement platform that includes the services needed for safe and secure living. The desire for such a comprehensive and integrated service system has emerged in Intel’s ethnographic work in the 92 nations where it has studied the aging experience, he said, and in conversations with seniors, their family members, and health care professionals.

In the beginning, the Chinese envisioned a system that would be operationalized at the street level. It was difficult for the people at Intel to envision a viable entity and infrastructure at that level of the social hierarchy, but they went along with the idea for a while, finally asking, “How many older people do you have on this particular street?” When the answer came back 893,000, “street-level” organization began to make a lot of sense. Dishman, using U.S. marketing terms, said that in urban areas, the Chinese hope to “build a branded sense of identity” among all the people who live on a particular street.

In villages, in contrast, one infrastructure would serve the entire population. Indeed, part of the challenge for the Chinese in designing this comprehensive service system is dealing with the scale differences from small rural settings to medium-sized towns to the existing large cities. One approach is to start over. Some 20 new megacities that will have this old-age-friendly city infrastructure in place are being built from scratch. The national government’s current 5-year plan includes starting these old-age-friendly cities initiatives, and by 2020, the Chinese hope to provide 90 percent of care for older people in their homes.

Both in Japan—where a tsunami erased the existing system—and in

China—where there is little installed infrastructure—planners are not burdened by past care models and can think about service delivery anew, along with the business model that will support it, and, finally, the technology needed to make the new models a reality. In contrast, the historic need to defend existing industries that do not want to disappear and that may be reluctant to transform is entrenched in the United States.

FROM MAINFRAME TO PERSONAL HEALTH

In the United States, what business processes and innovation techniques can change the model of care?, Dishman asked. “For a long time, I’ve been calling this a shift from mainframe to personal health,” Dishman said. Many workshop participants described the impetus for such a shift: the demographic imperative. By 2017, Dishman said, “we will have more people on the planet who are over the age of 65 than under age 5 for the first time in human history.” Aging populations and rising health care costs are phenomena worldwide. Many countries are “dealing with the triple aim [improving the quality of patient care, improving population health, and reducing the overall cost of care],” he said, even if they do not call it that. They worry about preventing the same costly chronic conditions that they see today in the cohorts that follow. They see the need for elder services outstripping the workforce, producing health care worker shortages and creating immigration challenges around the world.

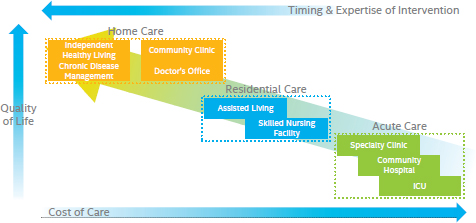

What they desire is to “shift left,” that is, to get more people on the end of the health continuum with lower levels of chronic disease, lower levels of functional impairment, lower costs of health care, and a higher quality of life (see Figure 3-1). Even for people with health problems, care can often be moved left in the diagram in Figure 3-1, he believes, from acute and residential care to home health care.

Innovations in policy or technology may help accomplish the move to the left in the diagram in Figure 3-1. The migration of technologies that help that happen is already occurring, Dishman said, especially in other parts of the world. He suggested that this migration of technologies raises significant questions for the United States, including the following:

- What are the safety and security implications?

- What does this migration mean from a regulatory perspective?

- How can skills be shifted so that people can start performing tasks considered to be the purview of the people on the right of the diagram in Figure 3-1, because there will not be enough capacity on the right?

- How is time shifted to the left in the diagram in Figure 3-1 so that preventive care and fundamental primary care can be done to pre-

vent those bad events that force people to the right of the diagram from ever happening?

Dishman noted that when his Intel team proposes any research or product development or policy work, it is held against this model and assessed for whether it will move care toward the left of the diagram in Figure 3-1 or help keep it on the left. It is not that hospitals and other institutions will disappear, he said, but they will be smaller, and capacity will exist elsewhere in the community. Capacity will be distributed to the home, the workplace, and elsewhere.

The Intel workforce was a test population for this concept, which was tested in three phases. At first, the effort was to encourage employees to sign up for consumer-directed health plans and to start to think differently about their relationship with their health plans. The second phase was the establishment on the Intel campus of Health for Life centers that included primary care and provided employees with risk assessment and follow-up coaching, as desired. Now, the company requires its providers to deliver home-based health care as the default model, to use telehealth and mobile technologies, and to track quality goals for individual employees and the workforce as a whole, which are the basis for payment.

Dishman acknowledged that Intel is learning as it goes along and is still “struggling to figure out this distributed capacity.” However, the workplace is a key node of care now and will become larger. He noted that this approach flies in the face of some 230 years of hospital history, which says

FIGURE 3-1 Intel strategy for innovation: shifts in place, skills, and time from the mainframe model to the personal health model.

NOTE: ICU = intensive care unit.

SOURCE: Reprinted with permission from Eric Dishman, Intel.

that, if you have a medical problem, you “make a pilgrimage to a place where the experts can be with their experts’ technology, and you time share that system, just like we used to time share the early computers.” Continuing the analogy, he said, “We couldn’t conceptualize back then that the power of personal computing was going to be that it would become truly personal. . . . It’s yours and you can do with it what you want.”

Health care needs to move similarly from a mainframe model to a personal health model, Dishman said. The mainframe model is simply the wrong tool for the job for the vast majority of care, he said. Around the world, Intel social scientists have mapped out people’s key nodes of health care, and although they mention their local hospital—for the most part, in a positive way—as their node of care, many other nodes of care exist. Furthermore, the people who are key to their care are not just hospitalists but also therapists, gerontologists, and the librarian who is helping them find information on the Internet. Every person has a different configuration for their “lived reality of health.”

In the future, the health care system will not be sustainable, he said, unless it first has an information system, a reward system, and a model of care that takes into account that sort of community-based care, with the home—and probably the workplace—being key nodes. Step one of moving from the mainframe to the personal health approach is distributing the capacity, he said, which depends on skill shifting, place shifting, and time shifting toward the activities that are leftward in the diagram in Figure 3-1.

The second requirement, he said, is for all the separate body parts and systems and for all the cellular-level understandings to be reintegrated into whole-person care. Even though the development of specialty care has been important in providing an understanding of the science behind health and illness, specialists easily become unintentionally biased by the drugs that they study, the problems that they understand, and the treatment approaches that are making their careers successful, he said. Patients who understand that their clinicians may have different backgrounds and motives seek second, third, fourth, and fifth opinions. “You don’t know what blinders any individual who is making these life-and-death decisions for you have,” he said.

The application of big data analytics to claims data may produce more robust risk assessments at the population level but may not inform the choices of an individual patient, Dishman continued. Consumer-generated data coming from smart phones and health applications can also feed the system to develop a model of care for the individual patient. For example, Intel is working with The Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research to capture consumer-generated data on Parkinson’s disease in a search for ways to monitor disease progression more carefully, to titrate medications more accurately, and to differentiate the different kinds of

Parkinson’s disease to look for treatment targets. “We have to have an informatics that can personalize care down to that level,” he said.

Finally, the inclusion of family members and neighbors as part of the care team requires new kinds of training and creates new kinds of care workers, as is happening in China, he said. Also required are incentives to track the quality of care that neighbors and family members provide. Technology can help with both monitoring and “anticipatory analytics” to assess the likelihood of problems, such as falls or medication lapses, before they happen. At the same time, efforts are needed to shore up social support and social networks. “If you can’t maintain the social network, then you have to rely on institutional systems,” he said.

Dishman identified the three pillars of personal health to be care anywhere, care networking, and care customization. The care anywhere concept represents the shift from institutions to mobile, home-based, and community-based care, with the understanding that today home health care can include a much broader range of options and produce care whose quality is much higher than that of traditional notions of home health care, tightly circumscribed as they are by policy, staff training, reimbursement, and client expectations.

Care networking includes the technology infrastructure, business models, and organizational models that allow care to be shifted from solo to team-based practice, along with the information technology systems that connect all these people and devices. Clinical decision support tools today are geared to the information needs of individual clinicians and not to teams of providers and not to trained family members and neighbors. Ideally, everyone in a care network for an individual should receive data updates and information on any changes in the care plan as the patient’s goals change or new clinical data or caregiver observations emerge. Dishman said, “Groupware for care decision support will be a key capability going forward.”

Care customization manages the shift from population-based to person-based treatment. Although that includes personalization based on genomics, it also means the use of people’s smartphones with intelligent algorithms that help them, for example, take their medications on time. Early experiments demonstrated that consistent positive behavior change is possible, as long as clinicians communicate with people in the way in which they prefer. Delivering the support for behavior change is easy to do now; “the hard part is figuring out what works and what does not” in the context of mass customization.

Several shifts of the health care system that would shore up the three

pillars are needed, Dishman said, and they can be supported by technology. Some examples include the following:

- Moving from professional care to more self-care. Dishman’s group has taught frail seniors to do self-care. These individuals are able to provide self-care if the technologies are usable and the benefits (the value proposition) to them are clear. Even if only 20 percent of patients can take on self-care, it would move the needle on cost, quality, and access, Dishman indicated. That 20 percent of patients would be the classic early adopters, and over time, more people will be able to take on the self-care tasks.

- Moving from transaction-based care to care coordination. Software tools can facilitate such a move by supporting teams, as mentioned above, and providing status reports in real time.

- Moving from “medical-ized” records to “life-ized” ones. Data that are broader than the data that are traditionally of interest to the medical community need to be included in the records for the patient, although whether those data will be included in different data systems or in some way combined into a single system has yet to be determined.

- Moving from stand-alone technologies to integrated ones. Telehealth and remote patient monitoring increasingly will not rely on specific devices but will be embedded into everyday devices. Technical and policy challenges exist, Dishman said, “but that world is coming.”

“We have to get out of this mind set that everything we need to do needs to be expensive, purpose built, and started from scratch.” Dishman said the future will also leverage technologies already on the diffusion-of-innovation path. They also will become increasingly less expensive and more widely available. An example is the automated external defibrillator, now a not-uncommon piece of consumer electronic equipment. The result is the consumerization of medical devices and the medicalization of consumer devices.

Another trend, he said, will be to enable clinicians to provide care wherever they are: in the clinic, in the hospital, in someone’s home, or in a community health center. The tablet computers that they carry will use an infrastructure that gives them access to all the information that they need, although he said that the technology industry will need to develop ways to facilitate the work flow for highly mobile clinicians.

For care customization, the shift to genomics and proteomics is happening rather quickly in cancer and rare inherited disorders, Dishman said, and the computing power needed is also becoming less expensive and more

widely available. Predictive modeling will enable more precise and therefore more effective therapies. Analysis of the information obtained by sequencing of a patient’s genome and analysis of the parts of the body that control the immune system, metabolism, or any other system that has gone wrong will allow custom drugs to be delivered.

The incorporation of patient goals and care plans into a medical record “is actually a pretty difficult machine-learning problem,” Dishman said. Although the creation of a database field called “patient goals” is relatively simple, the analytics that would allow the system to adapt to these goals and suggest ways to achieve them are not. Another data management problem that technology may be able to solve is automation of at least parts of the lengthy documentation tasks that home health care workers are currently required to perform. The time that it takes to complete these tasks subtracts substantially from the time that they have to spend with their clients, or if they hurry the job, the care activities that they perform may not be recorded—or reimbursed.

The results from the first attempt to use any of these systems have not been 100 percent accurate, even though they may have been a vast improvement over those obtained at the baseline, before implementation of the new system, Dishman said. This is another lesson from this work: “Will we wait and say the technology has to be perfect before we can actually use it?” he asked. The better approach will be to iterate over time, and even “the ‘good enough’ may provide some powerful interventions in quality.”

PRINCIPLES FOR THE EVOLUTION OF HEALTH CARE

Rather than a focus on technology, Dishman suggested a set of principles that will facilitate the evolution of health care and the previously described “shift to the left” (see Figure 3-1):

- Shift the place of care to the least restrictive setting.

- Shift skills to patients and caregivers and stop fighting the licensure and protectionism turf wars.

- Shift the time of care so that it is proactive and not reactive.

- Shift payments from individual providers to teams of providers of care and shift payments so that outcomes that reflect the use of a holistic approach are achieved.

- Shift the technology used from specialized equipment to everyday life technologies, but do it within a framework that does not start with technology.

The starting point for these changes, Dishman said, is the social covenant that asserts, “We as a culture have decided this is how we’re going to

set ourselves up for people who need care and those who provide it.” From that, evolve government policy and a framework that includes a financial system. Within that framework is a networked model of care that has a work flow. Within that model of care is embedded the technology. In other words, to use innovation to overcome the demographic dilemma, the social covenant and care models need to be used as the starting point, he said. All the other fundamental decisions about care models, work flows, workforce needs, and optimization of resources for results, followed by determination of sustainable business and payment models, need to come before it is determined what technology infrastructure is needed to support it.

Dishman said that home health care today is “relegated to a niche,” to an additional capability to be added to the mainframe model. His challenge to the workshop participants was to think about the workforce and business models that will be needed so that home- and community-based health care can become the default and hospital-based care—according to the mainframe model—becomes the exception.

An open discussion followed Dishman’s presentation. Workshop participants were able to give comments and ask questions. The following section summarizes the discussion session.

Steven Landers, Visiting Nurse Association Health Group, asked about the immediate opportunities to achieve benefits from the expansion of home health care, short of conceptually changing the whole health care system, even, he said, if the kind of evolution toward “care everywhere” is the ultimate goal. Dishman responded that those who provide home health care and long-term services and supports, even though they are sort of a backwater for mainframe care and are often not taken seriously, are the parts of the system that actually understand what needs to happen in the new care model. Dishman said that at Intel he teaches a course on leadership and that one of the principles that he teaches is that great leaders balance between practical thinking and possibility thinking and must be able to do both. He believes that home health care could be one of the disruptive forces that make the rest of the health care industry recognize that whole-person care is needed, especially for older people but also for people of all ages.

Erin Iturriaga, National Institutes of Health, noted that Washington, DC, has 14 villages that are part of the village movement, according to the World Health Organization’s age-friendly city model, and that each village is attached to a wellness center. Nationally, she said, the movement is looking for support from cities and states rather than support from the federal government. She asked Dishman if he thought that this model, which sounds similar to what is happening in Japan, could work in the United

States. Dishman responded that by use of the village model, it should be possible to innovate in terms of the care model, the payment model, and the technology used and that if the village model is used long enough this mode of organization will become natural for the people who are involved. He suggested that these villages can become locations for real-life experiments. In general, real-life experiments are hard to come by, he said. Instead, people merely test pieces of a model or test them for too short a period of time and with workers who have to do their old jobs as well as whatever new components that the experiment includes.

Gail Hunt, National Alliance for Caregiving, said that on the previous day of the workshop it became clear that a lot of pressure exists to push more and more of the caregiving tasks off onto the family caregivers, whether or not they are willing or able to handle them. Shifting of skills must require an assessment of the primary caregiver’s capacity, Hunt said, as well as that of other family members who would be able to help. Dishman agreed, stating that this is part of his model. The term “family caregiver” can include neighbors and, in some cases, community health workers with various levels of training. Whoever it is, he said, that person is assessed for both their ability and willingness to perform needed tasks, and there are some incentives for them to be assessed. They may be trained in multiple areas—a little home repair, some social work, and clinical care relevant to chronic disease. “I don’t know what to call that person,” he said. The multiple demands that come into play are part of why the system that assesses quality needs to track the care being provided and make sure that caregivers are not overwhelmed.

Amy Berman, The John A. Hartford Foundation, expressed concern that progress toward supporting good-quality care at home is moving too slowly. In part, she said, this is because not enough geriatric expertise with which to develop the core of these infrastructures or the decision-making support exists and that not enough physicians and nurses are available to care for the older population. Dishman agreed that when no standards are in place, experts from mixed disciplines should be brought in to identify best practices. “One of the things that health care is not good at, almost anywhere in the world, is having a formal and iterative innovation process,” he said. In pilot tests, people focus on the wrong problems, they do not learn from past innovations, and they do not have an iterative mind set that, once they have met a baseline set of safety and security standards, says, “We don’t have to get it all right in the beginning.”