Larger contextual issues (e.g., population health, payment policy) have implications for how home health care may need to change to meet future needs. This chapter describes three presentations that explored overarching trends currently being seen and how they may affect planning for the future role of home health care.

Tricia Neuman

Kaiser Family Foundation

Home Health Care Under Medicare and Medicaid

In home health care, the typical silos of Medicare and Medicaid do occasionally interact and overlap, but they are not truly integrated, affirmed Neuman. Medicare is an entitlement program that covers Americans ages 65 years and older and people under age 65 years with permanent disabilities in a uniform way across the country. Medicaid, by definition, is more complicated because of the combination of federal requirements and the different eligibility and benefit rules of each of the 50 states. The low-income people who are eligible for Medicaid and who receive home health care services often are also covered under Medicare (and are referred to as dually eligible), which is their primary coverage.

Medicaid is frequently thought of as a program for long-term services and supports (LTSS), but home health care is not really that entity, Neuman

said. Home-based medical services (including nursing services; home health aides; and medical supplies, appliances, and equipment) are mandatory benefits under Medicaid, but the broader array of home- and community-based services is optional.1 Even so, states may impose limits on their Medicaid home health care programs. Five states have put limits on program costs, and 25 states and the District of Columbia limit service hours. The benefit is typically covered under fee-for-service arrangements, although many states are moving toward the use of capitation, she said. As in Medicare’s home health care program, a physician needs to provide a written plan of care for recipients to be eligible for home health care services.

Mandatory benefits for individuals who qualify for Medicaid home health care include part-time or intermittent visits by a registered nurse; home health aide services provided by credentialed workers employed by participating home health agencies; and appropriate medical equipment, supplies, and appliances. Physical and occupational therapy and speech pathology and audiology services are optional benefits. Fifteen state Medicaid programs allow recipients to arrange their own services, including providing payment to family caregivers. These self-directed services programs have generally proved successful in reducing unmet patient needs and improving health outcomes, quality of life, and recipient satisfaction at a cost comparable to that of traditional home health agency–directed service programs.

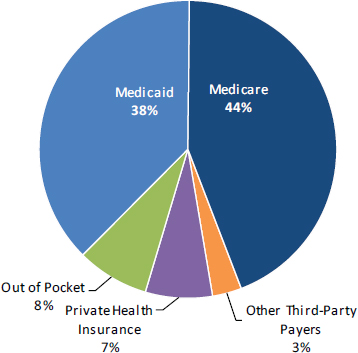

In the traditional Medicare program, which uses fee-for-service payments, it has been relatively easy to track how much that public insurance pays for various types of services, including home health care, Neuman said. However, as increasing numbers of Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries are moving into capitated plans, estimation of the number of people receiving services, how much they are receiving, and what government source is paying for these services becomes harder. Under fee-for-service programs, Medicare currently pays the largest share of home health care expenditures (44 percent), even with its relatively narrow eligibility criteria, followed by Medicaid (38 percent) (see Figure 4-1). Private health insurance and other third-party payers pay about 10 percent, and another 8 percent is paid out-of-pocket. Neuman noted that the amount of out-of-pocket spending is probably understated, because no reliable ways of capturing these data exist.

Home health care remains a relatively small piece of total Medicare and Medicaid spending. As noted above, the Medicaid expenditure may be an underestimate because such a large percentage of Medicaid recipients

______________

1 The broad category of home- and community-based services includes assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs), such as eating, bathing, and dressing; assistance with instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), such as preparing meals and housecleaning; adult day health care programs; home health aide services; and case management services.

FIGURE 4-1 Total home health care spending, 2012: $78 billion.

NOTE: Estimates of national health care expenditures on home health care also include spending on hospice by home health agencies. Total Medicaid spending includes both state and federal spending. Home health care includes medical care provided in the home by freestanding home health agencies. Medical equipment sales or rentals not billed through home health agencies and nonmedical types of home care (e.g., Meals on

Wheels, the services of workers who perform chores, friendly visits, or other custodial services) are excluded.

SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of National Health Expenditure Data, by type of service and source of funds, calendar years 1960 to 2012. Reprinted with permission from Tricia Neuman, Kaiser Family Foundation.

are in managed care plans, which are paid on a per capita and not a per service basis.

Who Is Served?

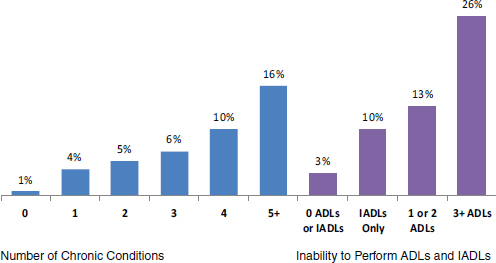

The utilization of home health care rises with the number of chronic conditions and the functional impairments that people have, Neuman said (see Figure 4-2).

About two-thirds of all Medicare home health care users have four or more chronic conditions or at least one functional impairment. “When

FIGURE 4-2 Percentage of beneficiaries using home health care, by characteristic,

2010.

NOTE: ADLs = activities of daily living; IADLs = instrumental activities of daily living.

SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of Medicare Current Beneficiary

Survey, 2010. Reprinted with permission from Tricia Neuman, Kaiser Family

Foundation.

you are talking about [people receiving] home health care,” Neuman said, “you’re talking about a population that is often physically compromised and cognitively compromised. These are people with multiple challenges.” Although most of these challenges arise in the context of aging, they also face the population of people with disabilities covered by Medicare.

Neuman presented data indicating that home health care usage overall, the number of home health care visits per user, and Medicare spending per user all rise with age, as does the use of many other health care services, including inpatient care, skilled nursing care, and physician services, and the use of some drugs (but not hospice care). The age–per capita spending curve for each of these services has a peak. For example, Neuman noted that physician services and outpatient drug spending peak at age 83 years, declining thereafter, and that after age 89 years, hospital expenditures start to drop. Spending on home health care does not peak until age 96 years, and spending on skilled nursing facilities peaks at age 98 years.

Although only 9 percent of the traditional (i.e., non-managed care) Medicare population receives home health care services, the health care spending for these individuals accounts for 38 percent of traditional Medi-

care spending. This is another reflection of their high degree of impairment and need. Neuman posed fundamental questions about these patterns of care, including the following:

- Are beneficiaries receiving care in the most appropriate setting?

- Are they receiving good-quality care in the place where they want to be?

- Does this pattern of care optimally balance federal, state, and family budgets?

- How will the nation finance care for an aging population?

Overall, the use of home health care services has increased in recent years, Neuman said, reflecting both an aging population and the rise in the incidence of chronic conditions noted earlier. However, spending on home health care, which had been rising concomitantly, has leveled off in recent years, even though home health care serves more people. It is not absolutely clear why this is, Neuman said, and then suggested that it may be due in part to payment reductions from the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA)2 and greater recent efforts to address fraud in some pockets of the country.

Effects of Policy Changes

Neuman stated that policy changes can spur innovations affecting home health care. These innovations are often aimed at the integration of systems of acute care and LTSS for dually eligible individuals and the development of team-based geriatric care. An example of such innovations, she said, includes the American Academy of Home Care Medicine’s Independence at Home initiative.3

How well home health care will fit into emerging models of care remains uncertain, Neuman said. Home health care is a relatively small player in these system reforms, and it will take effort to ensure that it can continue to play its important role, she said.

______________

2 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, Public Law 111-148, 111th Cong., 2nd sess. (March 23, 2010).

3 See http://www.iahnow.com (accessed December 24, 2014).

Douglas Holtz-Eakin

American Action Forum

Holtz-Eakin began his remarks by underscoring the “fundamentally unsustainable health care cost trajectory” that the nation is on, “even with the good news we have had about the pace of health care spending in recent years.” Federal budget deficits will grow relative to the gross domestic product, and in a decade, interest payments are projected to be larger than the U.S. Department of Defense budget, producing a tight money environment.

At the center of these difficulties, he said, are the programs that pay 80 percent of the home health care bills: Medicare and Medicaid. Medicare is spending its funds faster than payroll taxes and premiums are replenishing them and will come under increasing financial pressure. Medicaid faces similar pressures, especially at the state level.

The home health care industry’s financial condition looks especially precarious, said Holtz-Eakin, with some 40 percent of home health care providers expected to be in debt in just a few years. Moreover, new U.S. Department of Labor rules mandating overtime pay for workers not previously receiving it will boost agency costs, he said, if and when they go into effect. In the home, LTSS have been provided by family members, but in the future, this source of care will be less available, because family members will be working.

Despite this combination of pressures, opportunities also exist, Holtz-Eakin said. Keeping frail elders with chronic diseases and disabilities out of acute care could save a lot of money, so “the opportunity at the front end to really solve the Medicare cost problem is a serious one.” Research also suggests that home health care can play a substantial cost-saving role in post-acute care as well. To take advantage of such opportunities, the home health care sector will be required to document not just their cost savings but also the quality of the care that they provide. The combination of lower cost and high quality creates a value proposition for policy makers and taxpayers, Holtz-Eakin said. Further, the traditional dichotomy between health care services and LTSS needs to end, he believes.

Holtz-Eakin said that policy makers are “trying to fix these programs at the margins,” when what is needed is “a fundamental rethinking of how we deliver all these services.” Further, he believes, the voters will want to go with comfortable proposals, and “I’m not sure that will be enough to get this right going forward.”

Although technological advances have helped resolve a large number of major policy problems, in this situation, it is not clear what such an

advance would be, he said. For example, what agency will approve new health technology devices? Are health care applications going to be regulated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or by the Federal Communications Commission? When a service crosses state lines (as with telehealth), difficulties with state-based licensing and scope of practice regulations may arise.

Barbara A. McCann

Interim HealthCare

Several trends help describe the reality of U.S. home health care, as McCann sees it from her perspective as a medical social worker.

Limitations in the Design of the Medicare Home Health Care Benefit for Today’s Population

Most people are unaware of home health care services until a moment of crisis, when a staff member from the hospital, inpatient rehabilitation center, or nursing home advises them that their loved one is being discharged and arrangements for care in the home need to be made, McCann said. Thousands of Medicare beneficiaries who are older or have disabilities and their families have had to face this crisis and are receiving home health care, but the benefit is a poor fit to their needs, McCann said. Designed almost 50 years ago, the home health care benefit emphasizes recovery from acute illness and the opportunity for health improvement, and it presumes that the beneficiary’s health problems will end. It does not emphasize wellness or prevention, and it does not pay for comfort care or palliation at the end of life.

Patients receiving Medicare home health care services must be homebound, and once they are no longer confined to home, the benefit ends. However, “chronic disease goes on, [and] medications continue to come into the house,” McCann said. At that point, home health care providers have no one to hand the patient over to or transition to for ongoing care and coordination. Patient-centered medical homes solve this problem, she said, but they are far from universal.

Managing Continuous Transitions

Despite these challenges, home health care is being reinvented to serve as an important piece in the continuum of chronic care. In accountable care organizations, with their capitated structure, some providers are working

around the strictures of the Medicare home health care benefit and ensuring that patients receive the needed services. Transitions not only between care settings—especially hospital to home—but also during the period of time after a physician’s visit are times when patients definitely need help, even with an issue as basic as communication. “They can’t remember what they talked about or who they told about which symptom,” McCann said, “and they certainly can’t remember what the doctor told them to do or what medications to take.”

McCann noted that the home health care nurse can sit with the patient and family member or other caregiver and review medications, dosage schedules, and other medical instructions to help the family become organized about the patient’s health care needs. “The reality of health [care] in the home is the reality of the kitchen table. That’s where health decisions are made, and that’s where health is managed,” she said. Later in the workshop, Thomas E. Edes, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, agreed with this characterization, saying “the gold standard of medication reconciliation happens at the kitchen table.”

The most typical problems, McCann said, are

- Remembering to take medications,

- Knowing what the symptoms of problems are and when and from whom to seek help,

- Verifying that the individual or family member(s) makes an appointment with the community physician within 1 to 2 weeks post-discharge and that the individual has transportation,

- Making sure that reliable arrangements for meal preparation are in place, and

- Checking the patient’s ability to perform ADLs safely or whether arrangements are needed to make these activities easier or safer so that the individual can stay at home.

Finally, as a social worker, McCann emphasized the need for socialization by asking, “How [do] we keep people engaged daily?” Taking care of all of these important dimensions of care will be important to each patient and family well past the 30 or 60 days of Medicare’s home health care benefit or a post-acute care service.

Data Shortfalls

McCann said that many health care data exist but that almost no information on home health care is available. Since 2000, whenever a Medicare or a Medicaid patient has received skilled care, nursing services, or therapy at home, providers have had to collect more than 100 pieces of

data about that patient and service. This requirement holds whether the patient is covered by traditional fee-for-service Medicare, Medicare Advantage, Medicaid skilled care, or Medicaid managed care. “We have data on millions of episodes of care sitting in a database somewhere that have not been analyzed,” she said.

Although home health care providers receive some performance information, they do not know what combination of service timing, staff specialty, or coverage type results in better (or worse) patient outcomes. Nor do the available data reflect what additional personal care and support services not paid for by Medicare and Medicaid that the patient has obtained privately. It may be that these services make crucial differences to patient well-being.

New Program Models

McCann has encountered a number of hurdles to collaborative work in home health care that need to be overcome. For example, physicians assess pain differently than do physical therapists, and physical therapists assess pain differently than do home health agency personnel, she said. Nor do these three groups assess dependence in ADLs in the same way, making it more difficult to assess change or improvement. Furthermore, little common language for the establishment of outcome measures exists, she said.

Collaboration is likewise a feature of the demonstration programs for dually eligible individuals, she noted, in which the goal is better programmatic coordination throughout the continuum of care. This is to be accomplished through the integration and alignment of federal Medicare and state Medicaid funds into a single source of financial support for social as well as medical needs.

Home health care does not mean that a person is always in the home, McCann said. It may mean having a smartphone application that reminds a person to take medication;4 it may be the availability of a nurse or pharmacist via email or the telephone. Responsive cognitively appropriate and age-appropriate communication systems would help avoid unnecessary 911 calls.

This work involves more than managing illness; it means taking a wellness, preventive, and habilitation approach. She said, “I may not be able to [offer full rehabilitation to you], but I can help you live better in your home.” McCann concluded, “This is what we have to remember about the beauty of home care: it’s at home.”

______________

4 A participant noted that FDA has a guidance on mobile applications.

An open discussion followed the panelists’ presentations. Workshop participants were able to give comments and ask questions of the panelists. The following sections summarize the discussion session.

Definitions

Mary Brady, FDA, said that a standard definition of home health care is needed. The definition used by FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health includes concepts of wellness and the usefulness of devices not only in the home but also at school, during transport, or wherever a person is and includes whatever devices are needed to keep healthy those who are living well outside of a clinical facility, she said.

Families

Amy Berman, The John A. Hartford Foundation, asked how home health care should respond to the declining numbers and availability of family caregivers. In current policy, she said, these individuals are not part of the unit of care. Innovations to address that problem have not worked well, said Holtz-Eakin, but “the key to solving it is to get away from the silos” and to provide a broader range of services. Neuman emphasized that the data on the performance of some innovative models may not be available for a number of years. She said, “We need to get more evidence about how well those systems are working for seriously impaired people before we think that managed care and capitation will be a solution for care, even though they may be clearly a solution for budgets.”

One workshop participant commented that home health care needs to address not only cognitive and physical impairments but also the emotional needs of patients dealing with a new diagnosis and family members dealing with the exigencies of patient care.

Chris Herman, National Association of Social Workers, commented that difficult transitions do not end for families when hospice or home health care services appear. They reemerge each time that a new practitioner in that program goes into the patient’s home. Practitioners must continue to weave those programmatic connections together and help people understand them, she said. Neuman agreed, stating that the issue of transitions also needs to be thought about outside the hospital-to-home context. People in retirement communities, assisted living facilities, and other settings may not have family nearby for the kitchen-table conversations that McCann described.

Cynthia Boyd, Johns Hopkins University, asked about what is being

done to improve communication among patients and caregivers at home, home health care providers, and the rest of the health care system. McCann reiterated the importance of making sure that patients and their families understand their situation, what can be done about it, and whom to call. This information can be conveyed in multiple languages, through the use of drawings, or in other imaginative forms of communication so that individuals and families understand what is happening and what options they have. However, what is often needed, she said, is to have someone available to answer questions at the moment that they arise. Call centers that are linked to pharmacies can help individuals get answers to questions about medications. Sometimes, just having a live person to talk to can reduce a person’s anxiety. Communication of patient and family concerns back to other parts of the health care system is relatively easy in some of the more progressive patient-centered medical homes but is not so easy in other care environments. Said McCann, it should be explicit “who is responsible for those transitions and staying coordinated across time.”

Jimmo v. Sebelius

Herman also asked about the anticipated impact of the Jimmo v. Sebelius case5 and the resultant changes to Medicare for beneficiaries. Workshop participant Judith Stein, Center for Medicare Advocacy and a lead counsel in the case, responded. The case was brought on behalf of Ms. Jimmo and others as a national class action, she said, to address a long-standing problem that Medicare coverage is regularly denied on the basis of beneficiaries’ restoration potential and not on the basis of whether they require skilled care. For many people with long-term and chronic conditions, the likelihood of health restoration may be negligible, yet skilled care may well be required for them to maintain their condition or to prevent or slow its worsening. Stein said that the Jimmo case should help people receive the benefits that they are entitled to under the Medicare law and that will allow them to stay at home.

Cost of Care

Several workshop participants raised the issue of cost throughout the workshop. Namely, is home health care less expensive than the equivalent

______________

5 “On January 24, 2013, the U.S. District Court for the District of Vermont approved a settlement agreement in the case of Jimmo v. Sebelius, in which the plaintiffs alleged that Medicare contractors were inappropriately applying an ‘improvement standard’ in making claims determinations for Medicare coverage involving skilled care (e.g., the skilled nursing facility, home health, and outpatient therapy benefits)” (CMS, 2014).

care in a nursing home setting? Neuman responded that no good studies of this question have been conducted. The provision of comprehensive services full-time in the home would be more expensive than the provision of those services in a nursing home. Holtz-Eakin said that the focus should be on value and not just cost. What is needed, he said, is acquisition and analysis of the data on home health care to identify quality outcomes and best practices. As an illustration, Andrea Brassard, American Nurses Association, noted that her research on intensive home health care services in New York City in the 1990s found that these services did delay nursing home admissions and mortality among the sickest population. Holtz-Eakin noted that many studies have documented successful provider experiences and cost-saving business models with particular patient populations. However, to be suitable for adoption as part of the Medicare benefit, a study’s positive findings need to be generalizable to the population as a whole, he said, because “Medicare is for everybody.”

According to Brassard, the requirement that a physician sign off on orders for home health care or have a face-to-face encounter with the patient is inefficient and creates delays in dealing with patients’ problems. In most instances, she said, a nurse practitioner (NP), clinical nurse specialist, or physician assistant should be able to do this certification. Although the U.S. Congress has been concerned that allowing other health care professionals to certify that a patient requires home health care would increase costs by increasing the demand for home health care, the current inefficiencies are also costly, she said. Brassard asserted that the problem will become more acute in 25 to 30 years, when predictions indicate that one in every three primary care providers will be an NP; today that number is one in five. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO), which determines the cost of proposed legislation, has difficulty with projections that are long term, given that congressional policy making is mostly short term. Moreover, said Holtz-Eakin, CBO measures only costs, and if proposed legislation has nonmonetary benefits, organizations need “to get policy makers to advocate on behalf of those benefits.”

Erin Iturriaga, National Institutes of Health, raised the issue of the growing population of aging individuals in prisons. To save money, she said, states are releasing older long-stay prisoners early, shifting the costs of their care from the prison system to other payers, including Medicaid. Data on inmate health are not part of typical health care databases, and states have no way of budgeting for this influx.

Combining Medical Care and Social Needs

Michael Johnson, BAYADA Home Health Care, noted that different definitions of home health care seem to be constricted by the requirements of the programs that are paying for it. A broader conceptualization of

home- and community-based services may be needed. He asked how the Medicare focus on disease and drugs can be rebalanced with considerations about prevention and pre-acute care or about improving function, nutrition, and maybe even cognition. Holtz-Eakin responded that the current programs, as they exist, are not built for the future. The country’s approach is ad hoc, he said, and was invented through regulation and minor policy changes. Although it makes sense to take outcomes, including functional outcomes, as the focus, the Medicare program was designed almost five decades ago to serve people with acute-care stays and is now being asked to serve a population whose biggest problems are chronic diseases. The recent Senate Commission on Long-Term Care6 concluded that although significant program changes are needed, to provide more LTSS, there is no clear way to pay for them, Neuman said. She agreed that working with people early (providing pre-acute care instead of only post-acute care) to prevent functional decline would be an important strategy. Which provider will do this is uncertain: “There are a lot of people competing for that space,” she said. The mind set that long-term care is nursing home care must change, said McCann. Today, long-term care is simply the reality of chronic disease, aging, and disability. The evaluation of models from other countries—especially Australia—may help change that perception.

Bruce Leff, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, asked if the breakdown of silos among programs will emerge from new business models, including a greater penetration of managed care, or if it will require another big political battle. Holtz-Eakin predicted that both are likely but that change can certainly build on some of the essential organizational innovations currently under way. Regardless of the delivery model, however, payment should be made on the basis of patient outcomes. Meanwhile, it should be possible to build on Medicare Advantage and expand what it covers to include not just traditional health care services but also a continuum of health and social supports.

Terrence O’Malley, Massachusetts General Hospital, asked if realigning health care payments through accountable care and managed care organizations is increasing awareness of the importance of social factors in health. That does not seem to be happening as quickly as anticipated, he said. The panelists counseled patience, because promising new models are still only promising and it is too soon to pick winners. If these new models are allowed to run a while, the ones that are successful in reducing costs and improving quality will be revealed, Holtz-Eakin said. The ACA was just the beginning of a health care reform process that will continue for many years. What this workshop is about, he said, is getting home health care right in the end.

______________

6 See http://ltccommission.org (accessed December 24, 2014).