|

WORKSHOP IN BRIEF |

INSTITUTE OF MEDICINE Advising the nation • Improving health |

Crisis Standards of Care: Lessons from Communities Building Their Plans—Workshop in Brief

At the April 2014 Preparedness Summit in Atlanta, Georgia, the Institute of Medicine’s Forum on Medical and Public Health Preparedness for Catastrophic Events hosted a session to further the work on Crisis Standards of Care (CSC) and the fair and ethical allocation of scarce resources during a medical or public health emergency. The purpose of this learning session was to share lessons and examples from communities who have been working on developing their plans and to provide a venue allowing participants to discuss challenges they experienced or are anticipating as they begin this type of planning in their own communities. After hearing lessons from various perspectives including state health, local health, health care coalitions, and emergency medical services (EMS), participants had discussions on specific challenges and opportunities for advancement within different disciplines.

The discussions highlighted the critical role key stakeholders and facilitators play in developing CSC frameworks within each discipline, and how integrating medical surge plans into the emergency management system could improve disaster preparedness.

Background on Crisis Standards of Care

Dan Hanfling, Special Advisor for Emergency Preparedness and Response at Inova Hospital, provided an overview of the IOM’s continuum of care and an update on its most recent CSC report on indicators and triggers (IOM, 2013). Hurricane Katrina was the galvanizing moment that moved CSC to the forefront and made it clear that there was need for focus and attention on these issues, said Hanfling. He discussed the lack of situational awareness, absence of planning, and focus on reactive decision making that had occurred during previous catastrophic events, and how these situations highlighted the need for better CSC planning across jurisdictions.

In 2009, the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) asked the IOM to convene a committee to develop guidance for crisis standards of care in disaster situations. The report focuses on the key principles and guidance that can assist public health officials, health care facilities, and others in the development of systematic policies and protocols that can be applied in a disaster situation with scarce resources (IOM, 2009). The Haiti Earthquake in 2010 occurred shortly after its release and served as an evidence base for the application of some of the concepts highlighted in the first report, Hanfling noted.

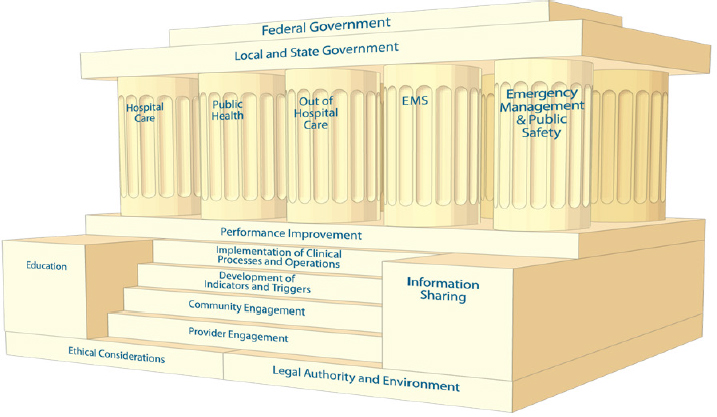

Following this, ASPR, the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) commissioned the IOM to reconvene the committee to develop practical templates and toolkits for specific disciplines to apply a systems framework to their CSC planning and implementation. The 2012 report Crisis Standards of Care: A Systems Framework for Catastrophic Disaster Response, was designed to help authorities operationalize the concepts of CSC (IOM, 2012). Hanfling noted that for the system to be a success, buy-in and participation from all sectors across the health care and emergency preparedness spectrum within a community is necessary. Engaging the community in these important decisions is also an integral part of the process, he said, so they included a “public engagement” template specifically to guide communities in hosting meetings and including citizens in their policy process. As shown in Figure 1, the foundation for successful

FIGURE 1 The foundation for CSC planning comprises ethical considerations and legal authority and environment, located on either side of the steps leading up to the structure. The steps represent elements needed to implement disaster response; education and information sharing are the means for ensuring that performance improvement processes drive the development of disaster response plans. The response functions are performed by each of the five components of the emergency response system: hospitals and acute care, public health, out-of-hospital and alternate care systems, pre-hospital and emergency medical services, and emergency management/public safety. While these components are separate, they are interdependent in their contribution to the structure; they support and are joined by the roof, representing the overarching authority of local, state, and federal governments.

SOURCE: Hanfling presentation, April 2, 2014; IOM, 2012.

planning and delivery of health care during disasters relies on all components of the emergency response system and community working together.

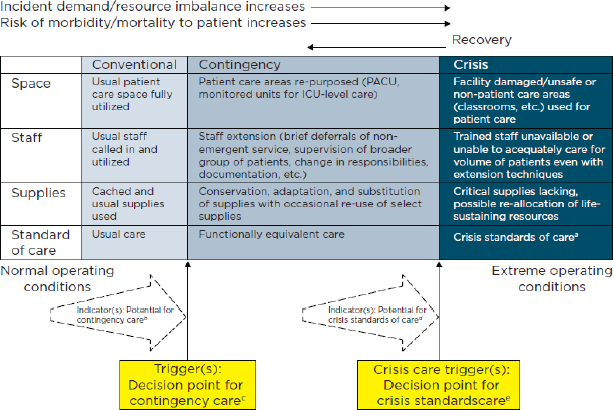

Finally, for the third phase of the study, the IOM convened a committee to more specifically define and distinguish the indicators and triggers (see Figure 2) that would cause a health system to shift from Conventional to Contingency to Crisis modes of care and back, including changes for staff, space, and supplies (IOM, 2013). The 2013 report considers the roles of each discipline in response to two scenarios: (1) a sudden-onset, no-notice earthquake, and (2) a slow-onset, pervasive pandemic. Hanfling noted the report also contains a discussion toolkit to help professionals begin conversations with stakeholders in their own communities, as well as specific toolkits tailored to: Behavioral Health, Emergency Management, Emergency Medical Services, Hospital and Acute Care, Out-of-Hospital and Alternative Care, and Public Health. The toolkits contain key concepts, guidance, and practical resources to help actors across the emergency response system develop plans for CSC and response to a catastrophic disaster. They are designed to help each discipline recognize actionable indicators in order to make more proactive decisions in their jurisdictions and guide implementation of transitions in modes of care that occur before, during, and after disaster strikes.

FIGURE 2 Allocation of specific resources along the care capacity continuum.

a Unless temporary, requires state empowerment, clinical guidance, and protection for triage decisions and authorization for alternate care sites/techniques. Once situational awareness achieved, triage decisions should be as systematic and integrated into institutional process, review, and documentation as possible.

b Institutions consider impact on the community of resource use (consider “greatest good” versus individual patient needs—e.g., conserve resources when possible), but patient-centered decision making is still the focus.

c Institutions (and providers) must make triage decisions balancing the availability of resources to others and the individual patient’s needs—shift to community-centered decision-making.

d Institutions continue to implement select adaptive strategies, but also may need to prepare to make triage decisions and shift to community-centered decision making.

e Institutions (and providers) must make triage decisions—balancing the availability of resources to others and the individual patient needs—and shift to community-centered decision making.

NOTE: ICU = intensive care unit; PACU = postanesthesia care unit.

SOURCE: Hanfling presentation, April 2, 2014; IOM, 2012.

Perspectives from Experience

State Health

Bruce Clements, Director of the Community Preparedness Section at the Texas Department of State Health, gave an overview of the Texas experience as they work to put CSC planning in place throughout the state. Texas began developing CSC in 2009 in response to H1N1, and started by developing an ethical framework to aid in decision making associated with the allocation and distribution of scarce state-owned resources. In 2010, with the help of University of Texas Medical Branch ethics staff, they were able to produce a comprehensive literature review and overarching document. In 2012, Texas drafted ICU and hospital triage guidelines, and finally in 2013, they were approved to develop the CSC initiative for the state.

To help with the project kickoff, Clements described a panel advisory group of subject matter experts, made up of both Texas State Health staff and non-staff members. This panel is charged with developing a medical ethics framework document for Texas that will serve as a compass to guide informed decision-making and the distribution of scarce medical resources during an emergency response, he explained. Beginning with this basic framework in late 2014, they hope to move next to creating appendices for state and local health, hospitals, and EMS by early 2015. Clements noted that Texas is also planning to begin holding community engagement meetings in 2015 and hopes to have a finalized plan by January 2016.

BOX 1

Michigan Hospital Scenario, as Presented by Linda Scott

There isn’t always a sentinel event or large disaster that indicates when to switch between conventional, contingency, and crisis phases of care, said Linda Scott, Health Care Preparedness Program Manager at the Michigan Department of Health. She used Michigan’s experience in the meningitis outbreak in fall 2013 to describe how one organization utilized the CSC framework when shifting from conventional to contingency care and back again. With 264 total cases and 19 deaths, Michigan had the highest number of meningitis cases in the country during this outbreak.a The particular facility she described had their first sign of shift to contingency status when they began incident command system (ICS) operations. Because of the patient load, they also had to use old patient units that were still available following a recent move, surge staffing, and move providers to 12-hour shifts, as well as seek additional requests placed through the health coalition to supplement staff during this contingency phase of care. Incident commanders at the hospital, state, and coalition levels had calls every day in order to build and then share situational awareness with other coalition members.

Additional pharmacy technicians were also needed, but since they are not typically included in the coalition request system, a special request had to be made for that type of assistance. Affected patients also required complex resources, she noted, including advanced technology and diagnostics. With 450 potentially impacted patients who needed follow-up and MRI tests, the hospital required double the capacity of staff to perform and analyze MRIs. Through the state, the hospital was able to request and obtain extra MRI machines to meet this increased need. An unexpected problem, however, involved insurance, which typically does not allow more than one MRI in less than 30 days. For all of the patients requiring multiple follow-ups, staff needed to connect with insurance companies to obtain approval.

Planning really impacted care delivery and improved outcomes, said Scott. There is also no clear line between the contingency care phase and a return to conventional care, she added. However, some indicators and triggers became apparent during the transition back to conventional care, including:

- Closing of extra medical units

- Decrease in patient volume

- Additional MRI machines available for return

- Reduction in necessary medical staff

ahttp://www.cdc.gov/hai/outbreaks/meningitis-map-large.html (accessed April 30, 2014).

Opportunities

- Progress in developing policies and guidance demands strong, independent subject matter experts as facilitators for meetings among stakeholders, explained Clements.

- Engaging licensing organizations early and having the right balance of legal representatives (both government and private sector) at the table can help move the process forward, Clements suggested.

Local Health

Suzet McKinney, Deputy Commissioner at the Chicago Department of Health, gave an explanation of why a local health department would begin difficult CSC planning efforts in Chicago and Illinois. CSC planning is now a part of both Public Health Emergency Preparedness (PHEP) and Hospital Preparedness Program (HPP) agreements under the medical surge capability requirement, she explained, linking it to funding sources. In addition this fiscal requirement, McKinney pointed out anecdotal stories, such as those in the book Five Days at Memorial: Life and Death in a Storm Ravaged Hospital (Fink, 2013) give emotional and personal reasons for completing this type of scarce resource planning. In order to be more prepared in a crisis, McKinney said providers should be able to rely on established protocols and community engagement connections made prior to an event, not individual decisions they make on an ad-hoc basis. She discussed the critical role of state leadership and involvement in the process, and how integrating coalition emergency operations plans into the city emergency plan framework could improve disaster management and response.

McKinney acknowledged that starting to develop CSC guidance and plans can seem daunting and overwhelming at first, even with the wealth of resources that the IOM provides, but encouraged session participants to start small and build progressively. The Chicago Healthcare System Coalition for Preparedness and Response developed a core planning team made up of members from a variety of disciplines, including public health, clinical emergency response, urban and rural health care, first responders, ethics, and poison control. Each member of the team was required to read the CSC reports produced by the IOM as well as Five Days at Memorial. Other recommended readings for planning team members included Muddy Waters: The Legacy of Katrina and Rita and Code Blue: A Katrina Physician’s Memoir to place their goals and objectives in context. In addition to this group, McKinney added that having an independent facilitator not beholden to a specific agenda or stakeholder group was important to help guide the process successfully.

Given the regulatory concerns that extend beyond a local level, McKinney explained that the city worked with the Illinois state health department from the beginning to ensure that CSC efforts were not duplicative. Once the core planning team was created, they mapped out a plan for conducting stakeholder engagement meetings in different regions throughout the state in the latter part of 2014. Using the Q-sort methodology, their goal is to determine sector specific values and opinions on CSC and allocation of scarce resources.1 A larger stakeholder conference is scheduled for early 2015, and McKinney said that the group has expectations for a final product in 2017.

A question about regulatory issues was posed by a participant from New Mexico about a past situation in which there was a NICU concern in the state and fines were given to hospitals who “overreached their licensing requirements” since the governor did not declare an official emergency. McKinney noted that this example underscores the importance of having these conversations ahead of time and collaborating at the state level so those kinds of accommodations can be made. Hanfling and Clements also pointed out emergency declarations can be retroactive and backdated if need be, and that regulations should not stand in the way of immediate and needed patient care in a crisis situation. They emphasized the importance of communication with legislators in order to craft broad liability protections during disaster circumstances.

Opportunities

- As more public health departments are included in coalitions, McKinney said developing CSC becomes the next step in “surge planning” and offers an opportunity for collaboration across sectors.

- Multidisciplinary planning that involves state leadership could ensure that CSC efforts are not duplicative, McKinney explained.

Health Care Coalitions

Linda Scott also emphasized the importance and relevance of the HPP agreement and meeting the Medical Surge Capability 10 from Healthcare Preparedness Capabilities: National Guidance for Healthcare System Preparedness, released by ASPR in 2012.2 She described how Michigan has developed a framework for incorporating collaborative CSC guidance into their work plan, particularly to satisfy Function 4 in the agreement. An important milestone was reached with the state’s development of its Guidelines for Ethical Allocation of Scarce Medical Resources and Services during Public Health Emergencies in Michigan, released to health care coalitions in July 2013. These guidelines were established as a set of criteria that can be implemented by decisionmakers in various circumstances during a disaster or other public health emergency. She explained that they are designed to be utilized in each region throughout the state, with assistance from health care coalitions in providing consistent planning and messaging across local environments. The guidelines are publicly accessible and can be found at http://mimedicalethics.org.

_____________

1 More on this type of community engagement can be found in the IOM workshop summary: http://iom.edu/Reports/2013/Engaging-the-Public-inCritical-Disaster-Planning-and-Decision-Making.aspx (accessed April 30, 2014).

2 For the full guidance on the 2012 Healthcare Preparedness Capabilities, see http://www.phe.gov/preparedness/planning/hpp/reports/documents/capabilities.pdf (accessed April 30, 2014).

Each region in Michigan is required to conduct educational sessions at advisory committees to introduce these ethical guidelines, explained Scott. Each health care coalition has been asked to focus at least one of their regional meetings on CSC and utilize indicators and triggers to facilitate localized planning and implementation exercises. Regional coordination by coalitions in the CSC planning stages is essential, she said, to facilitate a consistent standard of care for patients after a disaster across a geographic area. According to the phase 2 IOM report, “coordination allows the maximum use of available resources; facilitates obtaining and distributing resources; and provides a mechanism for policy development and situational awareness that is critical to avoiding crisis situations and, when a crisis does occur, ensuring fair and consistent use of resources to provide a uniform level of care across the region” (IOM, 2012).

Scott explained that regional operational guidelines also help to better understand the services, capacities, and capabilities of individual health care organizations within each coalition, and exploring this ahead of time can allow more efficient allocation and response. Additionally, health care organizations have been asked to establish organizational committees to facilitate crisis standards of care planning within their institutions. These clinical care committees, with diverse membership backgrounds, may work on an ongoing basis with emergency managers to identify and address scarce physical resources and assets as well as scarce specialist expertise that could be needed in an emergency. A participant from California added that they are doing similar work in their state with advisory committees and emphasized the need for an objective facilitator, as well as the critical need (and challenge) of engaging licensing boards to develop a strong and inclusive framework. Scott concluded by saying guidelines for a medical coordinating center have been created to provide assistance allocating scarce medical resources within the eight health care coalitions throughout Michigan.

Opportunities

- Health care coalitions have an important operational role in the fair and equitable treatment of patients, said Hanfling. They have the ability to assess and communicate situational awareness among providers to create a common operating platform, as well as broker patient load by lessening the burden on one hospital so that it is shared among various organizations.

- Since coalitions are at various stages of maturity, Scott noted, it may be helpful to identify subject matter experts who can engage key leaders within their respective sectors to participate and ensure that legal and legislative concerns are addressed at the state level. Hanfling added that this is also an opportunity for coalitions to come together and organize around what different planning principles look like within and across coalitions around the country.

Emergency Medical Services

Carol Cunningham, Medical Director for the Division of EMS within the Ohio Department of Public Safety, underscored the importance of EMS and first responders as critical partners in the CSC planning process and how well-developed medical coordination plans integrate them as partners throughout. She described the primary interfaces for EMS, including EMS medical directors, emergency medical dispatchers, health care system agencies, public safety agencies, and the local community. Dispatchers serve as the primary gateway between the public and the dispatch of resources, explained Cunningham, and it is their responsibility to ensure that scarce resources are appropriately delegated during an emergency response, so they should absolutely be included in this important planning process. “We have to stress the system to test the system,” said Cunningham. She noted that disaster training and drilling exercises can be a critical component of the preparedness process and that state EMS offices are essential partners in CSC planning.

Cunningham noted a few challenges from the perspective of EMS and first responders. These included

- Varying EMS scopes of practice by state.

- Communication systems—both internal and external may vary. Contingency communication systems, such as cell phone and radio communications, need to be examined, as they often fail during disasters.

- Incident command structure (internal and external).

- Varying protocols between counties and states—including dispatch, triage, treatment, transport.

The key to success, said Cunningham, is to employ collaborative, multi-agency planning that includes tiered, expanded protocols; multi-agency training exercises and drills; community engagement and education; and regular interfacing with surrounding jurisdictions.

Opportunities

- Including EMS at the beginning of the planning process would improve CSC management during an emergency response, Cunningham stated.

- Since EMS is a part of different agencies and departments depending on the state, it is important to address potential silos between state agencies, Cunningham explained, as well as differences between private and public ambulance services to form better and more efficient collaborative relationships during the development of CSC policies and guidance.

BOX 2

Crisis Standards of Care Resources, as Presented by Suzet McKinney

Visit http://www.iom.edu/crisisstandards for all of the IOM consensus reports and their templates, as well as related workshop summaries focusing on barriers to creating standards of care and public engagement guidance.

ASPR developed a “Communities of Interest” SharePoint site (i.e., a clearinghouse) to share ideas and resources regarding CSC and the allocation of scarce resources. Visit http://www.phe.gov/coi for all of the reports, as well as resources from HHS/ASPR, the RAND Corporation, and sample documents and tools from various jurisdictions to support this work.

![]()

Participants explored challenges and potential strategies for overcoming them from the perspective of each discipline in ensuing discussions. These strategies included engaging key leaders and stakeholders in developing medical surge plans and identifying independent, objective facilitators that could propel the CSC planning process forward, mentioned earlier by McKinney and Clements. McKinney referenced resources participants could use for more information in their planning process, which include sample plans and documents from jurisdictions that have begun this type of work (see Box 2). Several participants noted that additional guidance in stakeholder engagement would be useful for those just starting this type of planning and community outreach. As more and more jurisdictions begin conducting their own implementation, it would be helpful to capture these processes through meetings and published articles to ensure that various lessons are expressed and shared widely. Hanfling thanked the session panelists for sharing their insights and noted how motivating it was to see CSC planning be put to use in various disciplines. He encouraged participants to take what they had learned in the session back to their communities and let it shape their ongoing work in CSC.![]()

References

Fink, S. 2013. Five days at Memorial: Life and death in a storm ravaged hospital. New York: Crown Publishing.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2009. Guidance for establishing crisis standards of care for use in disaster situations: A letter report. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2012. Crisis standards of care: A systems framework for catastrophic disaster response. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2013. Crisis standards of care: A toolkit for indicators and triggers. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Forum on Medical and Public Health Preparedness for Catastrophic Events

Robert P. Kadlec (Co-Chair)

RPK Consulting, LLC, Alexandria, VA

Lynne R. Kidder (Co-Chair)

Consultant, Boulder, CO

Alex J. Adams

National Association of Chain Drug Stores, Alexandria, VA

Roy L. Alson

American College of Emergency Physicians, Winston-Salem, NC

Wyndolyn Bell

UnitedHealthcare, Atlanta, GA

David R. Bibo

The White House, Washington, DC

Kathryn Brinsfield

Office of Health Affairs, Department of Homeland Security, Washington, DC

CAPT. D. W. Chen

Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs, Department of Defense, Washington, DC

Susan Cooper

Regional Medical Center, Memphis, TN

Brooke Courtney

Office of Counterterrorism and Emerging Threats, U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Washington, DC

Bruce Evans

National Association of Emergency Medical Technicians, Upper Pine River Fire Protection District, Bayfield, CO

Julie L. Gerberding

Merck Vaccines, Merck & Co., Inc., West Point, PA

Lewis R. Goldfrank

New York University School of Medicine, New York

Dan Hanfling

INOVA Health System, Falls Church, VA

Jack Herrmann

National Association of County and City Health Officials, Washington, DC

James J. James

Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, Onancock, VA

Paul E. Jarris

Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, Arlington, VA

Lisa G. Kaplowitz

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC

Ali S. Khan

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA

Michael G. Kurilla

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Washington, DC

Donald M. Lumpkins

Federal Emergency Management Agency, Department of Homeland Security, Washington, DC

Jayne Lux

National Business Group on Health, Washington, DC

Linda M. MacIntyre

American Red Cross, San Rafael, CA

Suzet M. McKinney

Chicago Department of Public Health, IL

Nicole McKoin

Target Corporation, Furlong, PA

Margaret M. McMahon

Emergency Nurses Association, Williamstown, NJ

Aubrey K. Miller

National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD

Matthew Minson

Texas A&M University, College Station

Erin Mullen

Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, Washington, DC

John Osborn

Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN

Andrew T. Pavia

Infectious Disease Society of America, Salt Lake City, UT

Steven J. Phillips

National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD

Lewis J. Radonovich

Department of Veterans Affairs, Washington, DC

CAPT Mary Riley

Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC

Kenneth W. Schor

Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD

Roslyne Schulman

American Hospital Association, Washington, DC

Margaret Vanamringe

The Joint Commission, Washington, DC

W. Craig Vanderwagen

Martin, Blanck & Associates, Alexandria, VA

Jennifer Ward

Trauma Center Association of America, Las Cruces, NM

John M. Wiesman

Washington State Department of Health, Tumwater

Gamunu Wijetunge

National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, Washington, DC

DISCLAIMER: This workshop in brief has been prepared by Megan Reeve, Meghan Mott, Bradley Eckert, and Bruce Altevogt, rapporteurs, as a factual summary of what occurred at the meeting. The statements made are those of the authors or individual meeting participants and do not necessarily represent the views of all meeting participants, the planning committee, or the National Academies.

REVIEW: This workshop in brief was reviewed by MAJ Rodger Dale Jackson, Michigan Army National Guard, and Susan Finelli, California Department of Public Health; and coordinated by Chelsea Frakes, Institute of Medicine, to ensure that it meets institutional standards for quality and objectivity.

SPONSORS: This workshop was partially supported by the American College of Emergency Physicians; American Hospital Association; Association of State and Territorial Health Officials; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Department of Defense; Department of Defense, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences; Department of Health and Human Services’ National Institutes of Health: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institute of Environmental Sciences, National Library of Medicine; Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response; Department of Homeland Security’s Federal Emergency Management Agency; Department of Homeland Security, Office of Health Affairs; Department of Transportation’s National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; Department of Veterans Affairs; Emergency Nurses Association; Food and Drug Administration; Infectious Diseases Society of America; Martin, Blanck & Associates; Mayo Clinic; Merck Research Laboratories; National Association of Chain Drug Stores; National Association of County and City Health Officials; National Association of Emergency Medical Technicians; Pharmaceutical Research and Manufactures of America; Target Corporation; Trauma Center Association of America; and United Health Foundation.

For additional information regarding the workshop, visit http://www.iom.edu/Activities/PublicHealth/MedPrep/2014-APR-02.aspx.

Copyright 2014 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.