INSTITUTE OF MEDICINE

INSTITUTE OF MEDICINE

OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES

Advising the nation • Improving health

Collaboration Between Health Care and Public Health—Workshop in Brief

Drawing on the experience of practitioners and stakeholders in health and nonhealth fields, the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM’s) Roundtable on Population Health Improvement fosters interdisciplinary dialogue about factors and actions needed to improve the nation’s health. Population health refers to health outcomes across geopolitical jurisdictions that are shaped by access to clinical care, as well as behavioral, social, and environmental determinants of health (Kindig and Stoddart, 2003; Jacobson and Teutsch, 2012).

On February 5, 2015, the roundtable held a workshop in Washington, DC, titled “Opportunities at the Interface of Health Care and Public Health.” The event focused on how collaboration can facilitate conversation and action to achieve more meaningful population health solutions. The workshop was co-hosted with the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO)–Supported Primary Care and Public Health Collaborative.1 Both roundtable co-chair George Isham, senior advisor at HealthPartners, and ASTHO Executive Director Paul Jarris made short introductory remarks and welcomed participants.

This brief summary of the workshop highlights presentations and discussion sessions that followed, and it should not be viewed as conclusions or recommendations from the workshop. Statements made and opinions expressed are those of individual presenters and participants, and are not necessarily endorsed or verified by the IOM or the roundtable, and they should not be construed as reflecting any group consensus. A more detailed summary of the workshop proceedings will be available in 2015.

Context and Overview of the Day

José Montero, director of the New Hampshire Division of Public Health and planning committee co-chair, spoke of the broader array of partnerships between health and nonhealth sectors necessary to improve population health. He called for a conversation that goes beyond the discussion of payment reform and requires talking about finances in a broader sense. He added that improving asthma and high blood pressure control clearly requires not only high-quality care, but also consideration of the social determinants of health, including air quality, access to good housing, and the ability to partake in physical activity in a safe environment. These changes in multiple dimensions cannot happen “if we do not have a health care delivery system that really partners with everyone else.”

Julie K. Wood, vice president for health of the public and interprofessional activities at the American Academy of Family Physicians and a co-chair to the planning committee, provided the context and overview for the day. She introduced the four organizing topics: payment reform, the Million Hearts initiative, the hospital and public health relationship, and collaboration for asthma care.

Case Study 1: Payment Reform

In the first session, Sarah Linde, chief public health officer at the Health Resources and Services Administration, moderated the presentations and discussion about payment reform. Health care payment reform is the process of

____________

1 The collaborative was established in response to the IOM report Primary Care and Public Health: Exploring Integration to Improve Public Health (2012).

changing the payment system from one based on volume to one based on value, a shift accelerated in recent years because of the passage of the Affordable Care Act.

Ted Wymyslo, former director of the Ohio Department of Health and current chief medical officer of the Ohio Association of Community Health Centers, and Mary Applegate, medical director of the Ohio Department of Medicaid, spoke about partnering to advocate for health care delivery system reform in addition to payment reform in their home state. According to Wymyslo, the establishment of the Ohio Office of Health Transformation (OHT) brought health care services in the state under the direction of a single leader and allowed for joint decision making. This resulted in opportunities for greater collaboration between health care and public health practitioners. Applegate emphasized how consolidation exemplified by OHT allows communication to occur more easily so that stakeholders can work toward the same “end game.” Applegate cautioned, however, that communication may slow progress if participants take too long before acting on their agreed-upon goals.

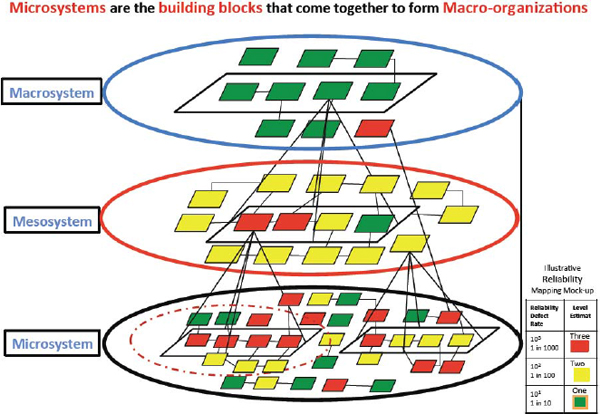

Applegate offered a familiar three-level framework, represented in Figure 1, for thinking about collaboration on a given health challenge: the microsystem (the service provider level), the mesosystem (the health system, hospital, or health plan level), and the macrosystem (state and national levels).

Applegate outlined challenges to alignment at the microsystem level. For example, laws to protect privacy such as the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act can prevent information sharing between a child’s school and a child’s health care provider (see, e.g., Barboza, 2008). But the person-to-person interaction at this level is fundamental in tracking and addressing health problems. Legal, cultural, and social challenges can be solved by bringing to the table community advocates, attorneys, and individuals with cultural competencies.

During the discussion, Jeffrey Levi from Trust for America’s Health asked how clinicians can link patients to social services in addition to determining patients’ needs, and how the health care and social services systems connect locally and at a higher level to close the gaps. Applegate replied by describing Ohio’s approach to lowering infant mortality rates by taking action targeted at the neighborhood level in partnership with local providers, health departments, and nonprofit organizations. To forge partnerships, she added, the first step is to communicate about the goal (e.g., decrease infant mortality), then show a path (e.g., ways to prevent preterm birth, seize opportunities to intervene), and also identify a few measures that will work across systems and that can be mapped geographically to help ascertain improvement.

FIGURE 1 The building blocks of macro-organizations.

SOURCE: Applegate presentation, 2015.

Wymyslo commented that another action step might be to better train health care providers to consider social determinants of health as a routine part of their practice. In Ohio, state legislation has helped facilitate interprofessional curriculum reform for physicians and other health providers who learn to provide team-based care. Initiatives like modernizing primary care and health care payment reform require retraining physicians, which is difficult and costly. Wymyslo suggested that it would be more efficient to change the curriculum of health care professionals during training, incorporating the teaching of newer methods for care of vulnerable populations.

Case Study 2: Million Hearts

The day’s second panel was moderated by Jarris and focused on the national Million Hearts initiative, which aims to prevent 1 million heart attacks and strokes by 2017. Million Hearts “brings together communities, health systems, nonprofit organizations, federal agencies, and private-sector partners from across the country to fight heart disease and stroke.”2 Partners include ASTHO, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), state and local health departments, and many others.

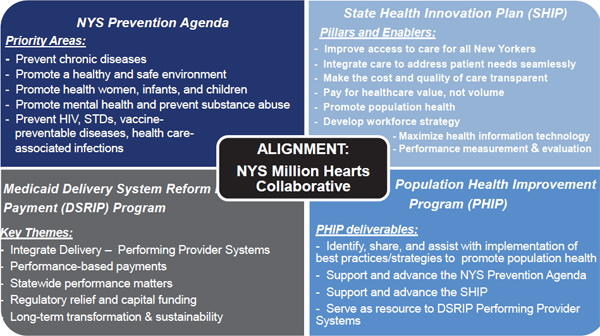

Jarris said that the sustainability of large-scale collaboratives like Million Hearts depends on funding that addresses nonhealth factors that contribute to cardiovascular disease instead of more traditional (i.e., disease-based) public health funding. Guthrie Birkhead of the New York State Health Department said successful cross-sector collaboration requires “leadership involvement at all levels.” Figure 2 illustrates how Million Hearts has been aligning goals and actions in New York state.

Birkhead explained how Million Hearts established new clinical treatment protocols, resulting in the delivery of better, more standardized care. These changes were innovative, for example, reconfiguring an exam room so blood pressure could be read without moving around, resulting in a more accurate reading, or standardizing blood pressure cuffs across clinical settings. Another marker of the collaboration between health care and public

FIGURE 2 Alignment of the New York State Million Hearts Collaborative.

SOURCE: Birkhead presentation, 2015.

____________

2 See http://millionhearts.hhs.gov (accessed April 22, 2015).

health this initiative pioneered was implementing a quality improvement (QI) process. Using a standardized QI measure to evaluate hypertension proved difficult at first; Jarris explained that many health departments and clinical systems were not prepared to use this metric. The initiative’s leaders and clinical providers collaborated openly, ensuring that patients reached through the Million Hearts initiative were entered into a registry using QI measures to demonstrate the initiative’s success.

Because payers asked what providers needed and incorporated those needs into goal metrics, the Million Hearts initiative has strengthened relationships and established a more successful collaborative. Integrating the National Quality Forum’s Measure 18 (NQF18)3 as a Million Hearts guideline (e.g., promoting the quality of hypertension care through aspirin therapy, blood pressure control, cholesterol management, and smoking cessation), helped physicians improve patient adherence.

Birkhead said that implementing the Million Hearts initiative at the state level depended on cooperation among city, suburban, and rural health centers. Electronic health records (EHRs) have limitations because they do not function as a registry; New York state had the good fortune of having its statewide network of health centers using the same EHRs package, which was a contributor to success. EHRs do not necessarily work well for patient management purposes because it is difficult to efficiently share data. For example, a managed care system will get a notification for reimbursement when a patient presents at the emergency department for care, but the patient’s primary clinician may not. Birkhead and others expressed hope that the data sharing could function as a “patient management tool,” better engaging those at the micro- and macrosystem level for individual and population care.

Jarris made the distinction between data and information. “There are tons of data out there,” he said, “just no information.” Jarris then pointed out that just having information does not directly translate into having the capacity for data-driven action. For example, Joseph Cunningham, vice president of health care delivery at Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Oklahoma, said his employer has one of the largest medical databases in the nation. Currently it has only claims data collected in a clinical setting, which is not helpful for predicting future trends or for planning.

Community outreach was a key ingredient to the success of Million Hearts; Jarris reported that about 89,000 people were reached during the initiative’s first year. Innovation went beyond the clinical setting to conducting blood pressure readings at public libraries. The increase in patients reached allowed clinics to have a more complete picture of health conditions in their community. In addition, several clinics enrolled in the program nationwide reported up to a 12 percent increase in their hypertension patients. In Washington, DC, alone, efforts to engage the community at this microsystem level identified 4,000 new hypertension patients in socioeconomically disadvantaged wards of the city.

During the discussion, Isham cautioned against drawing a community’s boundaries too wide, stating that sometimes national initiatives do not take into account geographic and regional differences. For instance, Million Hearts was difficult to implement in Minnesota because localized efforts had removed hypertension as a priority in local health plans. Jarris stated that future efforts will seek to remedy these types of problems.

Lunch and Conversation: Enhancing a Culture of Collaboration to Build a Culture of Health

During an interactive lunchtime session briefly reviewing the evidence on collaboration and highlighting some best practice methods, Paul Mattessich, executive director of Wilder Research, led a conversation with Lloyd Michener, professor and chair in the Department of Community and Family Medicine at Duke School of Medicine. Mattessich defined culture as involving “norms, values, attitudes, standards of behavior, assumptions, language, and vocabulary,” adding that there is not necessarily one common culture or definition that stakeholders use in their discussion of similar problems.

Michener emphasized the importance of the language he uses, noting that some words such as collaboration, alignment, network, and even population health have different meanings in different fields. Michener emphasized the need for careful communication planning to avoid confusion, making partnerships easier and more effective.

____________

3 The National Quality Forum is a not-for-profit, nonpartisan, membership-based organization that works to catalyze improvements in health care. For more information on NQF18, see http://www.nacdd1305.org/docs/NQF18slides.pdf (accessed April 22, 2015).

The language barrier can be even greater when working with nonhealth stakeholders in trying to improve population health, added Mattessich. Language, said Mattessich, “reflects disciplinary and cultural differences that have grown and evolved over long periods of time,” and he underscored the importance of consistency. For example, a health care provider, a social worker, and a teacher will all use different words to talk about the same individual—patient, client, and student.

Michener and Mattessich also talked about the importance of experiencing failure in partnerships, although those stories are told less often. Michener said that not experiencing failure may mean “you are not trying hard enough. In fact, I think it is the fear that gets in the way [of action].” He advocated for a change in thinking, saying that failure should be seen as “practice,” just like playing a game or riding a bike as a child. Failing, said Michener, “is learning to work together.”

Although it is important for a leader to be committed and possess political will to collaborate in health improvement efforts, Phyllis Meadows of the Kresge Foundation told attendees that “a huge amount of skill and competency and readiness” are needed to be effective. She added that will is not equivalent to skill, and partners also need the opportunity, “the space, and the resources” to collaborate.

Case Study 3: Collaboration Between Hospitals and Public Health Agencies

During the day’s third panel, Sunny Ramchandani, medical director of the Healthcare Business Directorate at the Naval Medical Center San Diego, moderated the discussion with Lawrence Prybil, Norton Professor in Healthcare Leadership and associate dean at the College of Public Health at the University of Kentucky, and Nicole A. Carkner, executive director of the Quad City Health Initiative. Echoing previous definitions, Prybil defined collaborations, or partnerships, as “independent parties coming together to jointly address a common purpose.”

Prybil presented a study that set out to identify successful partnerships among hospitals, public health agencies, and other population health stakeholders to offer lessons learned and recommendations based on these data and analyses (Prybil et al., 2014). After seeking nominations, the researchers analyzed the partnerships to find 157 that met baseline criteria for effectiveness and inclusion. Using this analysis, the study then identified 63 hospital–public health partnerships from across the nation. Fifty-five partnerships then responded to in-depth questions about goals, performance metrics, and partnership impact within the community. From among these 55 respondents, the study identified 12 exemplary and diverse partnerships. The study made 11 evidence-based recommendations for cultivating partnerships that place a high value on nurturing a culture of health and building trust within their communities (Prybil et al., 2014).

One of these 12 model partnerships was Quad City Health Initiative, which brought together five cities across Iowa and Illinois in 1999, and was inspired by the Healthy Communities Movement in the late 1990s.4 Ramchandani introduced Carkner’s presentation by saying that the initiative shows how to “engage a broad range of parties; build and maintain trust; state mission and goals; anchor institutions; [establish a] clearly defined charter; [and develop a] clear mutual understanding of population health, community health measures, and policy positions” through joint action. Carkner said that the partnership’s collective impact is made possible by its three core values of commitment, collaboration, and creativity.

Carkner indicated that the Quad City Health Initiative relied on a charismatic leader; a physician who was “very passionate about improving the health of the community” started the enterprise by talking with his board colleagues at two local nonprofit health systems. These systems became founding members. Carkner emphasized that the initiative aims to be the region’s “center for community health improvement.”

Carkner recounted that one of the first joint projects of the Quad City partnership was a community health assessment in 2002. In 2007, the partnership conducted another assessment, but this time incorporated the local United Way and civic organizations to better address the area’s nonclinical needs. As the initiative continues, the partnership is growing to facilitate better collaboration to meet the needs of its community.

____________

4 See http://www.preventioninstitute.org/press/highlights/1122-celebrating-25-years-of-the-healthy-communities-movement.html (accessed April 22, 2015).

Quad City Health Initiative has had fundraising success at the regional and national levels, but Carkner commented that sustainable collaboratives require committed leadership at the local level to ensure stable support over time. Prybil agreed, saying that the successful partnerships in the study found that an anchor institution able to make a long-term commitment can become a consistent base of support. Prybil added that having impact statements can provide evidence that anchor institutions’ involvement is improving the collaborative, making their continued participation more likely.

The conversation after the presentation turned to the cultivation of public–private partnerships. Several workshop participants voiced the opinion that while hospitals can be a stakeholder in population health partnerships, it should not be the responsibility of the hospital to be the sole initiator of population health efforts, especially when there are possibilities for public and private partnerships through public health departments, philanthropic associations, and government organizations.

Case Study 4: Asthma

The fourth and final panel of the day focused on asthma as a case study of public health–health care collaboration in a local context. Terry Allan, health commissioner of the Cuyahoga County Board of Health, moderated presentations and discussion with Margaret Reid, director of the Division of Healthy Homes and Community Supports at the Boston Public Health Commission and the Boston Asthma Home Visit Collaborative, and Shari Nethersole, executive director for community health at Boston Children’s Hospital and assistant professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School.

Data from the 2012 National Health Interview Survey show that more than 10 million children in the United States have asthma (National Center for Health Statistics, 2012). Allan indicated that the problems of asthma can “pile onto the compounding disadvantages of poverty,” contributing to lost school and work days for children and parents, contributing to cyclical economic disadvantages and a widening opportunity gap. In Boston, a program funded by community benefits, grants, and philanthropy to target the base social asthma triggers has begun to tackle population health matters.

Asthma treatment provided by the Boston Asthma Home Visit Collaborative involves clinicians referring patients for care in concert with public health and partner agencies to identify and mitigate in-home triggers of asthma attacks. Each child with asthma receives three free home visits to assess and address conditions in the home (e.g., clutter, mold, dust, pests, tobacco smoke, and household chemicals). Community health workers are trained to work with family members, helping them adhere to medical treatment, set goals for asthma control, and keep the home environment free of triggers. The families’ goals for asthma control are taken into account in this collaboration. According to Reid, the community health workers making the home visits are “full participants in the collaborative,” and these efforts to be inclusive contribute to the program’s success.

The initiative relies on data; for example, Nethersole said that 70 percent of hospitalized children came from six specific zip codes in Boston, and having these data allows the collaborative to target areas of greatest need. Nethersole also indicated that there was a high return on investment, making the case for developing payment models to make the program sustainable. When the initiative began, 1 year’s worth of asthma treatment cost insurers $3,000 per person with asthma. After 2 years, this cost dropped to $750. Within 1 year, there was a 57 percent decrease in emergency room visits and 80 percent decrease in hospital admissions. Missed school days were decreased by half. Improvement has continued during the program’s 8 years.

Reid noted that the collaborative extends to payers—Neighborhood Health Plan, a New England-based Medicaid managed care organization plan, pays for a small part of the services. Additionally, Asthma Center Partners, Tufts Medical Center, the federal Housing and Urban Development Healthy Homes program, and the federal EPA all provide funding for the collaborative. Another partner, the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, has hired a consultant to conduct a needs assessment and make recommendations for infrastructure requirements to sustain a statewide system of reimbursed community health workers for asthma home visits. Needs identified include standardizing training—including knowledge and skills assessment—and easy referral mechanisms for the service.

During the panel discussion, Nethersole indicated that the collaborative is increasingly looking to the future, for example, by providing training to new medical residents to incorporate social services referral into their care.

Reflections and Reactions to the Day

Mattessich closed the day by providing his summation of meeting highlights, listed below. Following this, he elicited audience reflections.

- Collaboration between health care and public health requires interaction with nonhealth sectors, and in the case of collaborative coalitions, members must reach out to partners to demonstrate the collaborative’s worth as an investment (Isham, Nethersole, Ramchandani).

- Data sharing is necessary for better collaboration between health care and public health. Though difficult in part due to the size and diversity of the population that public health agencies serve, data sharing and methods are central for quantifying the outcomes of collaborative efforts. It is important for future planning and ensuring sustainable funding (Allan, Carkner, Cunningham, Jarris).

- There is little published evidence describing and examining failures of collaborative efforts. Reports on failures can inform current efforts and planning for future collaborations (Isham, Mattessich, Montero).

- The current funding structure of the health care delivery system is such that it pays for sick care, and this can be a challenge to public health–health care collaboration, which by its very nature promotes a culture of wellness, not just treatment of disease (Applegate, Cunningham, Mattessich).

- Leaders must have common goals from the beginning for successful collaborative efforts. A skilled leader can find creative ways to leverage and align existing resources toward the collaborative effort (Applegate, Carkner, Meadows).

- Communication is important for any collaborative effort. It unifies definitions to help partners speak the same language, and facilitates both vertical and horizontal integration. Communication must extend beyond practitioners and providers to the populations they serve, and this requires trust (Applegate, Mattessich, Michener).

Links

ASTHO (www.astho.org)

Blue Cross Blue Shield of Oklahoma (www.bcbsok.com)

Boston Asthma Home Visit Collaborative (www.bphc.org/whatwedo/healthy-homes-environment/asthma/Pages/Boston-Asthma-Home-Visit-Collaborative.aspx)

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services State Innovation Models Program (http://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/state-innovations)

Health Resources and Services Administration (www.hrsa.gov)

HealthPartners (www.healthpartners.com)

Kresge Foundation (www.kresge.org)

Million Hearts (http://millionhearts.hhs.gov)

National Quality Forum (www.qualityforum.com)

Naval Medical Center San Diego (http://med.navy.mil/sites/nmcsd/Pages/default.aspx)

New Hampshire Public Health (http://dhhs.nh.gov)

New York State Department of Health (www.health.ny.gov)

Ohio Office of Health Transformation (http://healthtransformation.ohio.gov)

Quad City Health Initiative (www.genesishealth.com/qchi)

U.S. Public Health Service (http://usphs.gov)

Wilder Foundation (www.wilder.org)

References

Barboza, S., et al. 2008. HIPAA goes to school: Clarifying privacy laws in the education environment. Internet Journal of Law, Healthcare, and Ethics 6(2).

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2012. Primary care and public health: Exploring integration to improve population health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Jacobson, D. M., and S. Teutsch. 2012. An environmental scan of integrated approaches for defining and measuring total population health by the clinical care system, the government public health system, and stakeholder organizations. Washington, DC: National Quality Forum.

Kindig, D., and G. Stoddart. 2003. What is population health? American Journal of Public Health 93(3):380-383.

National Center for Health Statistics. 2013. National Health Interview Survey public use data release 2012. Washington, DC: National Center for Health Statistics.

Prybil, L., F. D. Scutchfield, R. Killian, A. Kelly, G. Mays, A. Carman, S. Levey, A. McGeorge, and D. W. Fardo. 2014. Improving community health through hospital–public health collaboration: Insights and lessons learned from successful partnerships. Commonwealth Center for Governance Studies.

Roundtable on Population Health Improvement

George Isham (Co-Chair)

HealthPartners, Inc.

David A. Kindig (Co-Chair)

University of Wisconsin

Terry Allan

National Association of County and City Health Officials and Cuyahoga County Board of Health

Catherine Baase

The Dow Chemical Company

Gillian Barclay

Aetna Foundation

Raymond J. Baxter

Kaiser Permanente

Raphael Bostic

University of Southern California

Debbie I. Chang

Nemours

Carl Cohn

Claremont Graduate University

Charles Fazlo

HealthPartners, Inc.

George R. Flores

The California Endowment

Jacqueline Martinez Garcel

New York State Health Foundation

Alan Gilbert

GE Healthymagination

Mary Lou Goeke

United Way of Santa Cruz County

Marthe R. Gold

New York Academy of Medicine

Garth Graham

Aetna Foundation

Peggy A. Honoré

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Robert Hughes

Missouri Foundation for Health

Robert M. Kaplan

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

James Knickman

New York State Health Foundation

Paula Lantz

The George Washington University

Michelle Larkin

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

Thomas A. LaVeist

Johns Hopkins University

Jeffrey Levi

Trust for America’s Health

Sarah R. Linde

Health Resources and Services Administration

Sanne Magnan

Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement

Phyllis D. Meadows

Kresge Foundation and University of Michigan School of Public Health

Bobby Milstein

ReThink Health

Judith A. Monroe

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

José Montero

Association of State and Territorial Health Officials and New Hampshire Division of Public Health Services

Mary Pittman

Public Health Institute

Pamela Russo

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

Lila J. Finney Rutten

Mayo Clinic

Brian Sakurada

Novo Nordisk, Inc.

Martín José Sepúlveda

IBM Corporation

Andrew Webber

Maine Health Management Coalition

Roundtable Staff

Alina B. Baciu

Director

Colin F. Fink

Senior Program Assistant

Amy Geller

Senior Program Officer

Lyla Hernandez

Senior Program Officer

Andrew Lemerise

Research Associate

Darla Thompson

Associate Program Officer

Rose Marie Martinez

Director, Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice

DISCLAIMER: This workshop in brief has been prepared by Jessica Nickrand, rapporteur, as a factual summary of what occurred at the meeting. The statements made are those of the authors or individual meeting participants and do not necessarily represent the views of all meeting participants, the planning committee, or the National Academies.

REVIEW: To ensure that it meets institutional standards for quality and objectivity, this workshop in brief was reviewed by Lila Rutten, Mayo Clinic, and Laura Snebold, National Association of County and City Health Officials. Chelsea Frakes, Institute of Medicine, served as review coordinator.

This workshop was jointly hosted by the Institute of Medicine and the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials–Supported Primary Care and Public Health Collaborative.

This workshop was partially supported by contracts between the National Academy of Sciences and the Aetna Foundation (#10001504), The California Endowment (20112338), Kaiser East Bay Community Foundation (20131471), Kresge Foundation (101288), Missouri Foundation for Health (12-0879-SOF-12), New York State Health Foundation (12-01708), and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (70555). The views presented in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the organizations or agencies that provided support for the activity.

For additional information regarding the workshop, visit www.iom.edu/PHandHC.

For more information about the Roundtable on Population Health Improvement, visit www.iom.edu/pophealthrt or e-mail pophealthrt@nas.edu.