2

Human Health, Public Health Practice, and Community Resilience

BOX 2-1 Important Points Highlighted by the Keynote Speaker

- Environmental health management approaches increasingly will emphasize resilience and sustainability to address complex environmental health issues.

- To guide policy development and planning, researchers should develop and use metrics for resilience that include factors related to health, socioeconomics, the environment, and community structure.

- The scientific literature remains inadequate to answer many of the questions clinicians and members of the public have about the health effects of the Deepwater Horizon (DWH) oil spill or the risks of future oil spills.

- Psychosocial impacts may be the most important negative outcomes of an oil spill. Research is needed to understand the factors that contribute to and mitigate these impacts.

- Activities initiated after the DWH disaster have led to the development of research cohorts, academic–community partnerships, and programs to build health capacity that the Gulf Research Program can learn from and build upon.

- Research opportunities for the Gulf Research Program include advancing the science of community resilience, oil spill toxicology, individual exposure assessment, and cumulative risk assessment.

- The public health community needs to make sure they are at the table during the response to an oil spill and demonstrate that it can play a valuable role.

In his keynote presentation, Bernard Goldstein, emeritus professor of environmental and occupational health and former dean of the University of Pittsburgh School of Public Health, provided an overview of the major concepts and issues to be discussed at the workshop, including the relationship between public health and resilience and lessons learned from the DWH oil spill and other disasters. He also discussed some possible areas of research that could support the strategic vision of the Gulf Research Program

HEALTH, RESILIENCE, AND SUSTAINABILITY

Goldstein began by noting the difficulty of addressing today’s environmental health management challenges using standard approaches of “command and control” and “risk assessment and management.”1 While these approaches will remain useful, he said, the field also needs new ways to think about the many existing—and emerging—complex environmental health challenges. He predicted that over the Gulf Research Program’s 30-year duration, environmental health management approaches will increasingly emphasize the concepts of resilience and sustainability.

To ground discussion at the workshop, Goldstein characterized the concepts of resilience, health, and sustainability. The Gulf Research Program, in its strategic plan, characterizes resilient communities as human

____________

1 According to Goldstein, command and control refers to the prescriptive approaches derived from the first wave of environmental laws passed by Congress and signed by President Richard Nixon that accompanied the formation of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 1970. As measurements of pollutants and their effects became more sophisticated, and the value of pollutant control more evident, additional focus was placed on assessing the widely ranging risks of individual agents and mixtures. The risk assessment and risk management paradigm began to be codified through a framework provided by a 1983 NRC report (NRC, 1983). More recently, the EPA has moved toward incorporating sustainability considerations while continuing to employ command and control and risk assessment and risk management.

communities that “anticipate risk, limit impacts, recover quickly, and successfully adapt when faced with adverse events and change” (Gulf Research Program, 2014). The Gulf Research Program also uses the definition of health developed by the World Health Organization: “Health is a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” (WHO, 1946). With regard to sustainability, Goldstein referenced the classic definition of sustainable development established by the Brundtland Commission of the United Nations: “Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (Brundtland Commission, 1987). Quoting Howard Frumkin (Dean of the University of Washington School of Public Health), Goldstein noted an important distinction among these definitions related to time. Definitions of resilience and sustainability acknowledge what could happen in the future whereas the same concept of time is not built in to the definition of health, although it is implicit in the focus on maternal and child health. The involvement of public health in the multigenerational aspects of maternal and child health issues highlight the importance of sustainability and of resilience.

The concept of resilience has helped researchers understand a variety of complex systems, from companies and ecosystems to the human body. Common characteristics of resilient systems can be summarized by the following basic principles developed by Joseph Fiksel at Ohio State University:

- Resilience is an intrinsic characteristic of all complex, self-organizing systems.

- A system is influenced by cycles of change at multiple temporal and spatial scales.

- Resilient systems respond to shocks or stresses by absorbing, adapting, or transforming.

- Resilient systems have feedback loops that help to maintain a dynamic equilibrium.

- A system may cross a threshold and shift to a different equilibrium state, or “regime.”

As an example of a threshold, Goldstein pointed to the extra energy in Hurricane Katrina that caused levees to be overtopped or breeched. “A little bit of a shift can make an enormous difference,” he said.

Goldstein also referenced key concepts of resilience identified by Bruneau and Reinhorn (2007) from their analysis of seismic resilience for acute care facilities:

- Robustness: The ability to withstand a given level of stress or demand without suffering loss of function

- Redundancy: The extent to which systems are substitutable

- Resourcefulness: The capacity to identify problems, establish priorities, and mobilize resources when conditions exist that threaten to disrupt

- Rapidity: The capacity to meet priorities and achieve goals in a timely manner in order to contain losses, recover functionality, and avoid future disruption

One way to think about the relationship between sustainability and resilience is to consider the classic question of whether the glass is half full or half empty, Goldstein said. For sustainability, the glass is twice as large as it needs to be and capacity needs to be “rightsized” because more effort is too costly. For resilience, the glass needs to be larger than half size because contending with unanticipated disruptions and change will require extra capacity. The question, asked Goldstein, is, “How much larger does it have to be?” Definitions are only important if they have an impact on actions, and planning is the mediator between definitions and actions.

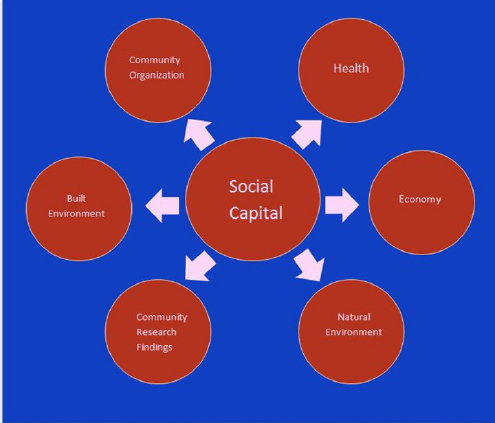

In a complex and turbulent world, resilience may be a prerequisite for achieving sustainability. Indeed, resiliency plays an important role in achieving certain sustainability targets, Goldstein said. For terrestrial biomes,2 the key determinant of resilience is human activities—with more and more people competing for fewer and fewer resources. Human activities have decreased the resilience of many biomes, with potentially negative implications for sustainability. However, this trajectory can be reversed if the appropriate actions are undertaken. For communities, the key determinant of resilience is social capital,3 which can lead in many directions, both positive and negative. Social capital consists of many components, including community organizations, health, the economy, and the built environment (Figure 2-1). “Put all these different things together and you end up with a community that is more resilient,” Goldstein said. For example, in Chicago during a heat wave, communities with more social structure tended to do better than those with less (Klinenberg, 2002). There are also data suggesting that increased social capital is correlated with lower suicide rates (Kunst et al., 2013).

Research on social capital and resilience is being conducted all over the world, but we need metrics to better understand how different factors influence resilience, he said. How can resilience be measured? It is easy to talk in generalities, but we need to get specific about resilience in a way that provides guidance for

____________

2 A biome is a major ecological community type, such as tropical rain forest, grassland, or desert.

3 Social capital can be defined as the features of social organization—such as civic participation, norms of reciprocity, and trust in others—that facilitate cooperation for mutual benefit.

FIGURE 2-1 A variety of factors influence social capital, which is a key determinant of community resilience. SOURCE: Presented by Bernard Goldstein on September 23, 2014.

planning and practice. “If, at the end of 30 years, we are still talking about it and don’t have something we can measure as having been accomplished, it is not going to be a meaningful exercise,” he said.

Public health does many things well that are relevant to advancing the science of resilience. For example, understanding how environmental, health, economic, and social factors influence resilience is an interdisciplinary undertaking, an approach that is inherent to public health. Complex public health problems, Goldstein noted, can only be solved by collaboration among its component disciplines–behavioral and community health sciences, biostatistics, environmental health, epidemiology, and health care policy and management. Public health can be instrumental in developing models and metrics for understanding resilience, especially if it can effectively engage with a broader set of disciplines.

Some sources of variability or change for which resilience can improve outcomes are not controllable at the source by humans (e.g., sunspots, hurricanes, earthquakes), but others are. In “public health-speak,” Goldstein said, “accidents are events that cannot be prevented, but incidents can.” In the case of oil spills, public health should target prevention of incidents by working with engineers and others to promote a safety culture within the offshore oil industry. The DWH oil spill was an incident, he said, not an accident.

HEALTH AND RESILIENCE AFTER THE DEEPWATER HORIZON OIL SPILL

Understanding the context of the DWH oil spill is of overwhelming importance when thinking about its impacts, Goldstein said. For example, the Gulf States tend to rate very poorly when compared with the rest of the United States on major health indicators, such as the percentages of adults with poor or fair health, low-birth-weight babies, smoking rates, obesity, or insurance coverage. This background of poor health conditions, which is linked in part to socioeconomic status, does not create optimal conditions for response or recovery, he said. “If the same kind of oil spill occurred off the coast of Puget Sound and you had these very upscale communities or islands being affected, you would have a very different level of resilience.”

Two months after the DWH oil spill the Institute of Medicine held a workshop to examine effects on human health. Take-home points from the workshop included (IOM, 2010):

- The DWH oil spill represented a failure of safety culture.

- Exposure assessment is central to linking chemical toxicity and effect.

- Psychosocial impacts may predominate.

- Lack of trust or transparency has psychosocial impacts.

- Risk communication must be tailored to community understanding.

- Seafood safety is a central short-term and long-term issue.

Goldstein noted that traditional toxicology and environmental health concerns are reflected in just two points (exposure assessment and seafood safety) and the other four points highlight broader cultural and psychosocial issues. The importance of these aspects of the disaster is underscored by the following observation made by the workshop summary authors, Goldstein said:

In addition to the physical stressors, the Deepwater Horizon oil disaster has disrupted delicate social, economic, and psychological balances in communities across the Gulf region. Local fishermen and fisher-women … are grappling with possibly permanent disruptions to their long-standing livelihoods … Communities question the safety of their most vulnerable populations and worry about the effects that the Gulf oil disaster will have on their immediate and long-term health. The resulting uncertainty about physical, social, and economic health has profound implications for the psychological well-being of individuals in affected communities. (IOM, 2010, emphasis added)

In Goldstein’s view psychosocial impacts have predominated to date. As an example of factors that can contribute to psychological distress, Goldstein observed that a major component of a dispersant widely used in the Gulf was initially not disclosed because it was proprietary. This component turned out to be the most widely sold over-the-counter laxative in the United States. Goldstein said that, as a toxicologist, he was not worried about something that Americans consume in such large quantities. But keeping this information secret weighed heavily on the community.

The same effect can be seen in surveys done in communities affected by shale gas development, Goldstein noted. For example, Ferrar et al. (2013) found that the top six stressors in Pennsylvania residents who believe their health has been affected by shale gas activities are: being denied information or being provided with false information, corruption, having their concerns or complaints ignored, being taken advantage of, financial damages, and noise pollution. As this survey indicates, lack of familiarity and lack of trust can potentially amplify health impacts. In Texas, people are more familiar with oil and gas production than in Pennsylvania. Over time, familiarity may increase in Pennsylvania, said Goldstein, but trust may not. With oil spills, people will always be angry because of perceptions of what was done to them. “We can’t ignore this social amplification of risk, and we need to know more about it,” Goldstein said.

Goldstein also pointed to boomtown effects that are secondary to cleanup activities when an incident occurs. Boomtown effects are due to sudden influxes of mostly young males from outside of the community, who earn money and can bring with them problems of alcoholism, drug abuse, traffic incidents, violence, and sexually transmitted diseases. Some places are better able to deal with these problems than others, he said, depending on the extent to which a jurisdiction is willing to acknowledge, understand, and counter them.

Goldstein highlighted several health-related studies and activities that have been initiated with funds related to the DWH oil spill (Table 2-1; see also Appendix E), including the Gulf Long-term Follow-up study (GuLF STUDY) funded by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS). He stated that this is a crucial activity that the Gulf Research Program should not duplicate. However, it may be possible to build upon this study by developing new protocols to gain additional information from the established cohorts.

Goldstein pointed out an important limitation of the GuLF STUDY: the lack of a system to quickly set up the study and to collect critical baseline data. As Lurie et al. (2013) pointed out, “Federal agencies and nongovernmental entities developed and rapidly established a roster of exposed workers and conducted important research, but there was no uniform, systematic collection of baseline data through surveys and biospecimen archives. Ultimately, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) supported a longitudinal study of exposed workers, but data collection did not begin until nearly 10 months after the spill.” Some important biological markers for benzene exposure, Goldstein noted, would not be present 10 months after exposure. NIEHS is working on protocols to be set up before an event occurs so that relevant data can be collected immediately.

Goldstein also highlighted the work of four NIEHS-funded Deepwater Horizon Research Consortia grantees; these are based at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, Louisiana State University, Tulane University, and the University of Florida. These centers have formed partnerships with community organizations and are taking a transdisciplinary approach to answer community health concerns. The Tulane University Center for Gulf Coast Environmental Health, for example, encompasses community engagement, environmental health sciences, maternal and child health, psychosocial health, cultural anthropology, and physiology.

TABLE 2-1 Selected DWH-Related Programs with a Focus on Health and Resilience

| Gulf Long-term Follow-up Study (GuLF STUDY) | NIEHS intramural program: prospective study of nearly 33,000 adults involved in oil spill cleanup or support. The study cohort was enrolled between March 2011 to March 2013 and received baseline interviews on cleanup jobs, symptoms, and health. |

| DWH Research Consortia |

NIEHS extramural program ($25.2 million over 5 years): Four university–community partnerships working to determine if there are or were harmful contaminants in air, water, and seafood stemming from the oil spill and assessing their health impacts.

|

| Gulf Region Health Outreach Program |

A capacity-building program, funded through the Deepwater Horizon Medical Benefits Class Action Settlement at $105 million over 5 years, with the goal of creating more resilient communities through regional partnerships. Primary Care Capacity Project: Louisiana Public Health Institute (Eric Baumgartner) Mental and Behavioral Health Capacity Project: University of Southern Mississippi (Timothy A. Rehner) University of South Alabama (Jennifer Langhinrichsen-Rohling) University of West Florida (Glenn E. Rohrer) Louisiana State University (Howard J. Osofsky) Environmental Health Capacity and Literacy Project: Tulane University (Maureen Lichtveld) Community Health Workers Training Project: University of South Alabama (J. Steven Picou) Community Engagement: Alliance Institute (Stephen Bradberry) |

SOURCE: Presented by Bernard Goldstein on September 23, 2014.

Goldstein also reviewed work that he has been involved with as part of the Gulf Region Health Outreach Program (GRHOP). GRHOP will use $105 million from the Deepwater Horizon Medical Benefits Class Action settlement to integrate primary care, mental and behavioral health, and environmental health, he said, with the goal of promoting health and resilience in the Gulf region. While GRHOP is not a research program, its activities are being evaluated. He noted that the findings from these evaluations may provide important guidance for the Gulf Research Program on how to build resilient communities.

Many of the scientists and public health professionals involved in GRHOP were also involved with the response to Hurricane Katrina. In essence, these earlier experiences have served as a baseline for the DWH responses, and “having these baselines are crucial if you are going to measure impact and see what works and what doesn’t work.”

The Gulf Research Program can also learn from other disaster centers across the country, such as those that conducted research in the aftermath of other disasters, for example, 9/11 and Hurricane Sandy in 2012.4 In addition, relevant research is being conducted around the world, such as that of Kim et al. (2013) to determine the burden of disease attributable to the Hebei oil spill in Korea. The Gulf Research Program needs to take advantage of such efforts to understand the health effects of oil spills, he said, by working with and learning from this developing international community.

____________

4 “Sandy, as a hurricane and a posttropical cyclone, killed at least 117 people in the United States and 69 more in Canada and the Caribbean. Sandy ranks as the second-costliest storm on record at $68 billion. Hurricane Katrina of 2005 is the highest at $108 billion” (see http://oceantoday.noaa.gov/makingofasuperstorm).

POTENTIAL RESEARCH OPPORTUNITIES

Since the DWH oil spill, numerous publications have identified important research and capacity needs for improving the protection of human health related to oil spills. Goldstein began his discussion of research opportunities for the Gulf Research Program by reviewing findings from a selection of these publications. He concluded his presentation by discussing several broad areas of research that will benefit communities impacted by future oil spills

Learning from the DWH Oil Spill

Goldstein highlighted several important considerations for future research that emerged from the IOM’s 2010 workshop summary (IOM, 2010):

- Public health surveillance is essential.

- Worker health and community health are linked and must be considered together.

- Vulnerable populations should be the focus.

- Communities must be involved in research planning and execution, early and often.

- Public health research and evaluation must be disaster ready.

- Basic toxicological evaluation of weathered oil and dispersants is necessary.

- Exposure assessment should directly focus on the potentially exposed population.

Goldstein noted that the literature is still inadequate to respond to the many questions asked by clinicians and the public about the potential health impacts of the DWH oil spill. As summarized in an article he coauthored in 2011,

several initiatives are urgently needed, before similar disasters occur in the future: rapid development and implementation of protocols for baseline clinical evaluations, including respiratory function; biospecimen banking; short- and longer-term medical surveillance and monitoring of workers; and development of psychosocial interventions … especially for vulnerable populations. (Goldstein et al., 2011)

“We simply do not have a good database that can help researchers and clinicians answer these important questions,” he said. And, research is needed across four general categories of potential health effects of oil spills: (1) worker safety; (2) toxicologic effects in workers, visitors, and community members; (3) mental health effects from social and economic disruption; and (4) ecosystem effects that have consequences for human health (Goldstein et al., 2011). Understanding ecosystem effects, in particular, will require collaborative research with other disciplines he observed.

As a specific example of the difficulties that can arise in implementing these recommendations, Goldstein pointed to several research needs related to health risk for pregnant women:

- What are the reproductive and developmental risks of exposure to crude oil, “weathered”5 crude oil, dispersants, and mixtures?

- How do these compare with the risks of evacuating pregnant women from their community, including living elsewhere?

- Should pregnant women be advised against working on oil spill cleanups?

These questions are often more complex than they seem, he observed. For example, there may be a great deal of literature on the occupational health of workers in the crude oil industry, but not all spills are of crude oil, and crude oil workers are largely male. “We know next to nothing about the effects of weathered oil”, he said, or, about the kinds of risks faced by populations that are evacuated to an unfamiliar location away from their usual health care supports. “We need to know more about these risks to make better decisions when responding to oil spills”, he said.

Community Health and Resilience

Goldstein also pointed to requirements for research on determinants of community health and resilience related to responses to coastal oil spills. This research requires:

- Cross-cutting multidisciplinary approaches

- Community cooperation and involvement

- Public health agency cooperation and involvement

- Longer-term research support

- Interdependent projects

- Valid metrics of community resilience

Oil Spill Toxicology

Goldstein also pointed to major research needs related to understanding the toxicology of oil spills in gen-

____________

5 “Following an oil spill or any other event that releases crude oil or crude oil products into the marine environment, weathering processes begin immediately to transform the materials into substances with physical and chemical characteristics that differ from the original source material … Processes involved in the weathering of crude oil include evaporation, emulsification, and dissolution, whereas chemical processes focus on oxidation, particularly photo-oxidation. The principal biological process that affects crude oil in the marine environment is microbial oxidation” (NRC, 2003).

eral, particularly how these change over time. For acute effects, little is known about the acute human toxicology of “weathered” crude oil, dispersants, or mixtures. Research into subacute effects is also needed to inform better responses to concerns about whether seafood is safe for human consumption. And, very few studies have advanced understanding of the chronic effects of oil spills. For example, what are the long-term implications of exposure to weathered crude oil, Goldstein asked.

Cumulative Risk Assessment

Cumulative risk assessments attempt to integrate across all of the chemical risk factors to which an individual is exposed and through all of the pathways of exposure. Developing this capacity is seen as particularly relevant to environmental justice issues.6 However, Goldstein noted, the field does not yet have the right tools and methods to do this well.

Recent research has shown that social and behavioral factors can moderate an individual’s response to chemical exposures. For example, epigenetics—the study of heritable changes in gene expression caused by chemical modifications7 of DNA—can mediate effects of chemical and nonchemical stressors. Goldstein noted that accumulating evidence suggests that both chemical (e.g., methylmercury, cigarette smoke, benzene, lead) and nonchemical (e.g., psychosocial stress, famine, exercise, nutrition) stressors can induce epigenetic changes.

Former NIEHS administrator and director of the EPA’s National Center for Environmental Assessment Ken Olden has advanced the hypothesis that an individual’s set of epigenetic changes (their epigenome) may serve as a biosensor to monitor cumulative effects of exposure to multiple chemical and non-chemical stressors over the life course, Goldstein said. And, epigenetic modifications have been associated with a variety of diseases and disorders, such as cancer, diabetes, neurodevelopmental disorders, and mental health disorders, among others (Olden et al., 2014).

This is an emerging area of research that may help future generations to understand some of the health issues that arise during an oil spill, Goldstein noted. As this field develops over the Gulf Research Program’s 30-year duration, Goldstein said, it may contribute to capacity to conduct cumulative risk assessments and to a better understanding of important linkages between an individual’s health and their environment.

Individual Exposure Assessment

Goldstein concluded his presentation by discussing “what we can be doing, should be doing, but aren’t doing.” The following five elements, he said, are part of a complete exposure pathway:

- Source—How the material gets in the environment

- Media—Soil, water, or air in which a material moves from its source

- Exposure point—Where people contact the media

- Exposure route—How the material enters the body (e.g., eating, drinking, breathing)

- Receptor population—People who are exposed or potentially exposed

Environmental health researchers can predict what people are exposed to after an oil spill by looking at the first four elements, he observed, and while we do not really need to measure exposure in populations exposed or potentially exposed (receptor population), we should. The public is concerned and does not believe that researchers can take measurements made in the offshore environment and translate these measurements into exposure levels for individuals, based on wind or water currents or other factors, he said. “It doesn’t work that way. You have to measure where people are, and you have to measure people.”

Goldstein also emphasized the importance of consulting with the receptor population.

A good industrial hygienist … will not just measure at a place where the model shows the highest level of exposure will be. That good industrial hygienist will go to the workers who are concerned and say, “Where do you think the exposure is greatest? Where is area you are most concerned about?” It is important that the measurement be made there if one is really going to address the issue.

Making the Case for Public Health

Finally, Goldstein commented on the role of public health in the response to the DWH oil spill. “We in public health have not done the job we need to do in making sure that we are at the table, in pushing into these areas, in paying attention to the broader range of activities that can occur,” Goldstein said. With the DWH, insightful reviews have been done on the ways that science and engineering can contribute to the

____________

6 Environmental justice is achieved “when everyone enjoys the same degree of protection from environmental and health hazards and equal access to the decision-making process to have a healthy environment in which to live, learn, and work.” (see, http://www.epa.gov/environmentaljustice/).

7 Epigenetic changes include modifications to the cytosine residue of DNA (DNA methylation) and histone proteins associated with DNA (histone modification). These changes alter the expression of certain genes and are distinct from genetic mutations, which are chemical changes that alter the sequence of DNA.

response to the oil spill (Lubchenco et al., 2012; McNutt et al., 2012). But public health typically has not been represented in these studies. “This is a situation in which we have not made the case. We have not tried hard enough to be sure that we can be involved.”

The Gulf Research Program, with its 30-year duration and its clear statement of the importance of including public health, gives the public health community an opportunity to prove that it can play a valuable role in responses to oil spills, Goldstein concluded.