BOX 7-1 Points Highlighted by Individual Speakers

- Transdisciplinary research to understand socioecological responses and recovery following disasters can inform the development of best management practices to promote sustainable and healthy communities (Blum).

- Ecosystem services have emerged as a means to characterize ecosystems and link their functions with human health and well-being. This concept can be used to characterize baseline health of ecosystems and measure impact of stressors (e.g., oil spills, climate change) (Sandifer).

- Consortia that support interdisciplinary traineeships and are connected to Gulf communities could enable students to work with specific populations (Sandifer).

- Members of communities who work with fisheries and other coastal ecosystems can grasp complex ideas quickly and are a valuable resource for researchers (Peterson).

- Because their livelihoods are at stake, people from communities have the drive and passion to create change (Peterson).

- A forum for information exchange between the Gulf Research Program and other relevant programs, such as the oceans and human health centers could make needed links between related programs (Stegeman).

- Dedicated funds that can be mobilized quickly to support immediate postevent research are lacking. The 30-year window of the Gulf Research Program provides a unique second opportunity to document baseline health indicators in communities living in disaster-prone areas (Lichtveld).

- Leadership development across sectors, disciplines, and communities is a key opportunity for building lasting impact (Lichtveld).

The final panel discussion at the workshop considered two broad questions relevant to long-term planning of the Gulf Research Program: (1) Given the Program’s 30-year duration, what are some key opportunities to advance understanding of the connections between human health and the environment?, and (2) How can the Gulf Research Program support the development of health, scientific, community, and policy leaders who can address complex issues at the intersection between human and ecosystem health?

Presentations summarized in this chapter explore the possibility of funding a center in the Gulf region for integrative, cross-boundary research; identify opportunities to build upon important models and concepts that can drive cross-boundary approaches; and suggest funding mechanisms and other approaches that can help support the Gulf Research Program’s strategic vision.

A GULF CENTER LINKING HEALTH, SOCIETY, AND THE ENVIRONMENT

New Orleans, the southeastern Louisiana coast, and the Gulf Coast in general provide many opportunities to better understand socioecological responses and recovery following catastrophic events, observed Michael Blum, Eugenie Schwartz Professor of River and Coastal Studies and director of the Tulane/Xavier Center for Bioenvironmental Research. Such research can advance understanding of post-trauma conditions and yield outcomes that promote sustainable and healthy communities. He characterized three broad categories of opportunity—synthesis, coordination, and pipelines—for the Gulf Research Program to contribute to this work.

Examining how communities responded to and recovered from events like Hurricane Katrina or the DWH incident provides an opportunity to understand the

processes and drivers that lead to or promote healthy and sustainable communities, said Blum. Because the Gulf region encompasses tightly coupled human and natural ecosystems, research on post-trauma conditions can yield critical and novel understanding of how economic outcomes are tightly linked to environmental integrity (i.e., ecosystem services) and how community resilience is linked to the resilience of natural systems (i.e., socioecological resilience). Such interactions are dynamic and can lead to emergent processes and properties, he said. Ultimately, such research can lead to the development of best management practices, like restoring damaged wetlands, that incorporate and enhance the value of endemic ecosystem services (e.g., storm protection and water filtration) provided by coastal environments.

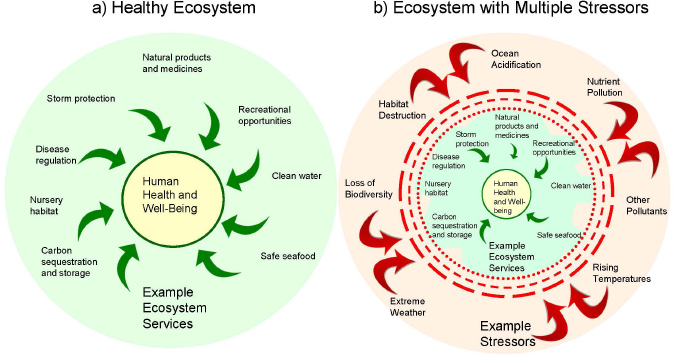

Blum illustrated the impact of interacting human and natural systems by briefly discussing research on the distribution and prevalence of pathogens in post-Katrina New Orleans. A traditional linear perspective draws a line from land use change to pathogen prevalence to disease incidence, but this view is “very outdated,” said Blum. A more realistic perspective is one that recognizes the coupled dynamic of human dimensions and natural dimensions and the processes that link those two categories. This kind of approach can also be applied to the DWH oil spill (Figure 7-1), where decisions made to remediate and restore coastal environments following the incident have influenced exposure pathways that put human and ecological communities at risk.

Developing this kind of perspective requires transdisciplinary research perspectives, which necessitates breaking out of disciplinary silos that are perpetuated by separate funding agencies with distinct missions. Providing support for transdisciplinary research through well-conceived grant competitions and supporting a center to encourage such cross-boundary work are distinctive opportunities for the Gulf Research Program. Existing national centers focused on oceans and human health probably come closest to filling this gap at present, but “There is no national center that effectively links health, society, and environment. The Gulf Research Program has the opportunity to do something unique here,” he said. For example, he said, we currently have silos of environmental assessments conducted by EPA and environmental analyses funded by the NSF, but “It is very rare that health assessments are linked and integrated from the get-go with environmental assessments.” This “strategic gap” is one that the Gulf Research Program could fill by providing support for integrative environmental and health assessments, he observed.

Blum urged the NAS to “step beyond its comfort zones” and look at opportunities other than its traditional workshops and consensus studies. For example, the Gulf Research Program could support leadership acad-

FIGURE 7-1 Opportunities for transdisciplinary research on socioecological responses and recovery following catastrophic events. SOURCE: Presented by Michael Blum on September 24, 2014; Image Credits: U.S. Coast Guard (upper right and left); Scott Zengel, RPI/NOAA (lower right and left).

emies that engage academics, community members, and others, or risk communication training for scientists, policy makers, and others. Such academies could offer training in community resilience and build awareness of human–environment interactions. These and other complementary activities, including the junior policy and senior research fellowships that have been created by the Gulf Research Program, could be centered on a new cross-boundary research center located in the Gulf.

The National Academies can succeed where others might fail because it is known for its transparency and trust, but it will have hurdles to overcome. For example, the organization is not an embedded member of the Gulf Coast community. Blum noted, “There needs to be a push for embedding the NAS into the community. The Gulf Research Program can play a strategic role in stewarding the community. It can provide guidance in ways that other institutions on the Gulf Coast haven’t done yet … You have 30 years. That’s a long period of time to become a rich and deep partner.”

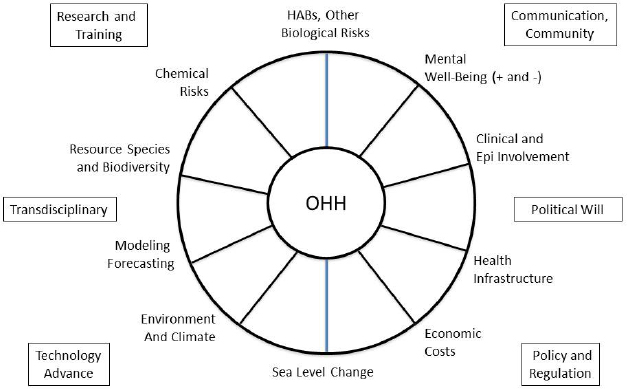

Speaking in his personal capacity, Paul Sandifer, chief science advisor for NOAA’s National Ocean Service, urged the Gulf Research Program to focus on ecosystem services and to quantify the values of these services to humans. Human health and well-being is the cumulative or ultimate ecosystem service, he said. Health and well-being result from a number of services provided by healthy ecosystems, many of which can be impacted by a variety of stressors (Figure 7-2) (Sandifer and Sutton-Grier 2014). For example, exposure to nature and biodiversity provides multiple health values to humans including a variety of psychological and physiological benefits, decreased inflammatory and other noninfectious diseases, tangible materials and resilience, and aesthetic, cultural, recreational, socioeconomic, and spiritual benefits. Thus, the loss of natural biodiversity may have important consequences for human health and well-being (Bernstein, 2014; Hough, 2014; Rook, 2013; Sandifer et al., 2015).

The mechanisms by which ecosystems provide these services are still poorly understood, said Sandifer, and present an important research opportunity for the Gulf Research Program. Specifically, he suggested four key foci for research:

- Determine ecological mechanisms by which natural biodiversity supports the production and delivery of ecosystem services in the Gulf of Mexico ecosystem.

- Increase understanding of the ways in which nature and biodiversity in the Gulf of Mexico ecosystem support human health, including biological mechanisms of action (e.g., effects on the human immune

FIGURE 7-2 Conceptual representation of human health and well-being as the focal point of cumulative ecosystem services in healthy and heavily stressed ecosystems. In a healthy ecosystem (a), the area that provides optimal ecosystem services of all kinds for the support of human health and well-being is large, regular and more or less stable. In heavily stressed ecosystems (b), multiple stressors simultaneously and cumulatively impact numerous ecosystem services, resulting in reduced amount, quantity, and stability of services for humans. SOURCE: Sandifer and Sutton-Grier (2014). Presented by Paul Sandifer on September 24, 2014.

-

system and other physiological and psychological processes) as well as how natural infrastructure confers storm protection and other benefits.

- Quantify how intact ecosystems and habitats within ecosystems can assist in the adaptation or mitigation of the effects of climate change and extreme events and how stressed systems may exacerbate climate change effects.

- Invest in the development of environmental health early warning systems such as expanded ocean observations and ecological forecasting capabilities (Sandifer et al., 2013).

Such research is essential to establishing baselines for healthy ecosystems, he said. “If you do not understand what a healthy ecosystem is, and what that means in terms of ecosystem services, you cannot understand the impact of incidents such as DWH or sea-level rise.” Over a 30-year period, the Gulf Research Program could significantly advance understanding by developing measurable and meaningful metrics for ecosystem services and the processes through which they affect human health and well-being.

Sandifer also discussed the Gulf Research Program’s potential role in training. One extremely successful component of the former NOAA Oceans and Human Health Initiative was its support for competitively designated university consortia that funded interdisciplinary trainees at the master’s, doctoral, and postdoctoral levels. Once trained in the ocean and health sciences, these trainees have gone on to work in academia; federal, state, and international agencies; nongovernmental organizations; and private business.

Sandifer suggested that the Gulf Research Program should support the development of similar interdisciplinary traineeship consortia, including social science and policy components. These traineeships should be connected to Gulf of Mexico communities to enable students to work with specific populations. In addition, support for a few internationally recognized distinguished scholars could help raise the visibility of the Gulf Research Program, provide role models and mentors for these students, and represent the Program’s science in high-level, high-impact situations. These scholars could also draw community, congressional, philanthropic, and private business attention to needed investments, policies, and actions, Sandifer said.

TAPPING INTO THE KNOWLEDGE OF COMMUNITIES

The traditional ecological knowledge that can be found in local coastal communities is in fact a manifestation of complex systems thinking (Rihani, 2002), said Kristina Peterson, an anthropologist and community-engaged scholar at the Lowland Center and the University of New Orleans. In the Gulf, for instance, the ways in which communities work with fisheries and other coastal systems enable them to grasp complex ideas very quickly—“far more so than what I have found academics to be able to grasp, because academics are so siloed,” Peterson said. “That’s a gift that communities can give to this process over the next 30 years.”

Another goal of communities is the conservation and comanagement of natural resources, said Peterson. Comanagement means that the community brings its local and traditional ecological knowledge into the discourse over resource management and resource recovery, as an equal partner. They have an equal voice in the oversight and protection of the “commons,” she said (Berkes 1999, 2008; Berkes and Folke, 1998; Berkes et al., 2005, 2003). For example, many people in the Gulf region have knowledge both of the oil industry and the fishing industry. “They know the complexity between the two, and they understand the regime change and the challenges that [these interactions] present.” Several examples of the community understanding include the participation of the expert commercial fishers in a state-funded research program carried out by University of New Orleans called Sci-TEK. The fishing community developed lesson plans that included fisheries, water flow, historic and proposed reclamation projects, and navigation. These lesson plans were part of the knowledge exchange that occurred between the fishers and state agency personnel that contributed to a new understanding of dynamic changing systems and restoration needs. Another instance that demonstrated the multidimensional understanding of oil and fisheries occurred after the BP oil disaster. The leaders of the “oiled” communities were quick to understand what potential impact the oil would have on estuaries; thus, they gathered fishers, political leaders, business owners, students, and others for investigative trips to the Prince William Sound Citizens Advisory Council. The exchange between the Alaskans and the coastal communities lead the Louisiana coastal communities to advocate for such an entity in the Gulf States region so there could be community-directed science that would address concerns communities see as present and potential risks between oil and the estuaries. The Gulf folks appreciated the science that has been and continues to be carried out for the Prince William Sound region through the Regional Citizens’ Advisory Council (RCAC), Peterson said.

Communities are also actively contributing to research in such areas as phenology; ethnobotany; shoreline erosion; biomimicry; monitoring and sampling of air, land, and water; climate change; adaptation strategies; mitigation; and experimentation, she said (Koppel-Maldonado et al., 2013; Laska et al., 2015; Peterson, 2014; Peterson et al., 2014; Peterson and Maldonado, 2015).

Community members from the Louisiana parishes of Lafourche, Plaquemines, and Terrebonne, for example, contributed to the National Climate Assessment. In another example cited by Peterson, a Gulf community is doing experiments with mushrooms that can eat oil and clean soil. “These are things that communities have taken on, on their own and on their own dime, without academics coming in or supporting them.”

In response to a question, Peterson noted that her organization has been studying how to effectively engage communities for more than 13 years. A key finding, she said, is that academics and representatives from state, local, and federal agencies learn more from community members when community members are peers at professional meetings, rather than when academics and agency representatives are “in the field,” visiting communities. Financial support of participation of community members at professional meetings or other venues where decisions are being made would be helpful, she said, and training programs to support engagement are also needed. Agencies and academics often speak in very different languages, she said, and it is often entirely on the shoulders of communities to become “multilingual.” Communication is a bridge that needs to be built, she said.

Because their lives and livelihoods are at stake, people from communities have the drive and passion to create change. “If they are not involved, you are missing a huge potential.” Community members need to be equal partners in research and interventions, said Peterson, with equally funded and equally represented voices. Peterson suggested that RCAC is a potential model for integrating members of the community, academy, and leadership in a very innovative and adaptive way. This would be an incredible resource for the Gulf region, she concluded.

LINKAGES TO OCEANS AND HUMAN HEALTH PROGRAMS

The Oceans and Human Health (OHH) Program, which is funded by NIEHS and NSF, supports activities to understand how coastal water systems and human populations interact and influence one another. In his presentation, John Stegeman, director of the OHH Center at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (http://www.whoi.edu/whcohh), reviewed the breadth of activities the program has been involved in over the past 10 years (Laws et al., 2008), and suggested that these activities could inform the development of Gulf Research Program initiatives.

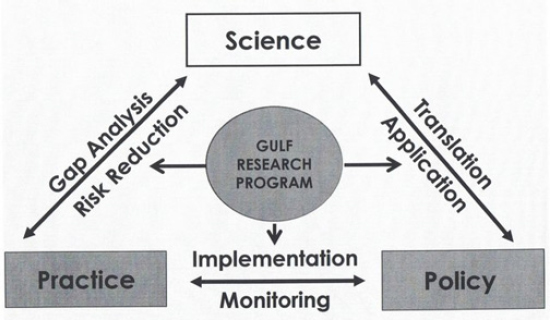

Oceans influence human health in a variety of ways (Figure 7-3), he said. In this complex system, drivers (e.g., environment and climate, biological and chemical risks) and targets (biodiversity, human physical and mental health) interact in complex ways that have both

FIGURE 7-3 Spectrum of Oceans and Human Health Program activities (outside boxes) and focus areas. SOURCE: Presented by John Stegeman on September 24, 2014.

positive and negative outcomes for coastal populations and ecosystems (Bowen et al., 2006). OHH programs have developed models of some of these interactions that can be used to forecast outcomes and protect human health from negative influences, such as Harmful Algal Blooms (HABs), he said. Some outcomes are much harder to evaluate, he said, such as the positive health benefits of recreational activities near the ocean, though studies do support such benefits (White et al, 2013). Research on the linkages, outcomes, and forecasting are among important needs, he said. OHH research topics are necessarily transdisciplinary, involving oceanographers, physicists, economists, epidemiologists, and genomic scientists, among others. Another program strength is its focus on technological advances to improve methods for sampling, measuring, and modeling. Beyond research and development, OHH program activities include communications, community involvement, political will, and policies and regulations.

The Gulf Research Program should take advantage of the work of the OHH program and of similar centers that are beginning, worldwide, such as in the European Centre for Environment and Health , he said. Establishing a forum for information exchange with OHH programs and others, such as the NIEHS DWH consortia and divisions of the CDC, (the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry and the Division of Environmental Hazards and Health Effects in the National Centers for Environmental Health) could explore possible connections among programs and opportunities to build upon existing data and activities. Stegeman further suggested that a committee or a forum might be a useful mechanism for gathering and synthesizing information from these programs.

INVESTING IN PEOPLE, PELICANS, AND PUPILS

The Gulf Research Program can be seen as operating in a “sandbox” with many related programs, players, and portfolios of research, said Maureen Lichtveld, professor and chair in the Department of Global Environmental Health Sciences at the Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine. In her presentation, she reviewed elements of the existing landscape and lessons learned, and offered suggestions for the Gulf Research Program to consider as it develops its research portfolio, approaches to research conduct and funding, and training and education programs.

Lichtveld began by matching topics from the current workshop with the objectives and recommendations drawn from a recent conference hosted by the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GOMRI):1

Objective 1: Health and resilience

- Strengthen the science of resilience.

Objective 2: Disaster and ecosystem change management

- Assess baseline health status of different target communities.

Objective 3: Environmental health risks

- Characterize background exposure levels in communities to examine health status trends over time.

- Design a new generation of cumulative exposure models.

- Promote the use of locally collected data to inform the risk assessment decision-making process.

- Prioritize inter- and transgenerational health studies in at-risk communities.

Objective 4: Innovation and partnerships

- Invest in cross-disciplinary partnerships.

- Develop effective methods to advance environmental health literacy.

Some of these recommendations have come up in the workshop, Lichtveld pointed out, but some have not and should be included in the Program’s research portfolio. She emphasized the need to prioritize taking advantage of “the work that is going on, but will end, such as the continuation of existing cohort studies.” Cohorts of pregnant women and their infants could support inter- and transgenerational studies, she said, and “We can’t miss that opportunity; it will be a crime to let those cohorts go.”

In addition, the research portfolio could include the development and testing of a recently proposed resilience activation network framework, which suggests that resilience can arise through community or individual resilience attributes or through exposure to harm, which in turn affects the mental health of individuals (Abramson et al., 2014). This framework is a potential resource to guide practice. For example, social indicators of community resilience could be developed, as described by Ross (2014), and used to guide responses.

Lichtveld also identified critical challenges hampering human health research design, implementation, and translation into meaningful, actionable findings benefiting vulnerable communities. For example, from a design perspective, environmental epidemiological investigations require baseline indicators to determine risk levels and ascertain how exposures potentially adversely affect a specific outcome or disease condition over time. Obtaining baseline measures soon after an event or exposure to chemical and nonchemical stressors is not feasible unless an “off the shelf,” field-ready approved research protocol can be activated. Efforts

____________

1 2014 Gulf of Mexico Oil Spill and Ecosystem Science Conference. See http://2014.gulfofmexicoconference.org/wp-content/uploads/2014_GulfConferenceReport.pdf.

currently underway by the Department of Health and Human Services and the National Library of Medicine may assist in overcoming this challenge. An equally important challenge is the lack of dedicated funds that could be mobilized in days rather than months or years to support immediate postevent research. The 30-year window of the Gulf Research Program provides a unique second opportunity to document baseline health indicators in communities living in disaster-prone areas. Disasters have four phases, Lichtveld explained: pre, during, post, and inter. The last phase, interdisaster, is the one that needs the most attention, she contended. For example, she pointed to seven factors that influence disaster readiness and capabilities:

- Density of predisaster populations

- Levels of isolation versus proximity to large metropolitan areas

- Extent of local infrastructure strength

- Robustness of local economy

- Availability of public transportation

- Consistent access to health and basic services

- Special population needs addressed

All seven—and especially the needs of special populations—are considerations in the interdisaster phase. Funding interdisaster research can provide a reasonable health status baseline upon which studies in the postevent response phase can build. Timing, Lichtveld indicated, not only affects the scientific yield of a disaster-related study but equally importantly also affects the establishment of viable, trust-based community–academic partnerships (Lichtveld, 2014). Engaging community partners at the earliest possible time, ideally not during or after, but in between disasters not only gives the partnerships time to mature but also creates a greater likelihood that communities are engaged in the research from design to translation and dissemination.

Because of its 30-year duration, the Gulf Research Program should carefully consider which activities need to be initiated early in its lifetime, she said. In her view, the Gulf Research Program should prioritize developing a transdisciplinary pipeline, across industry, policy, community, and academic spheres. There are many models that could guide the development of this pipeline, such as programs that embed college students in middle schools2 (service learning), support “emerging scholars” that are junior and seniors in high school,3 training to link research with practice skills, link training with research funding, support bi-directional policy scholars—to bring science to policy makers and policy makers to the academic setting—and developing a leadership academy to develop “research navigators.” The Gulf Research Program could support innovations by building on such existing programs through new projects funded under its education and training theme or providing opportunities to embed such pipeline projects as part of career development within both the human health research and ecosystem monitoring portfolios.

The Gulf Research Program should also carefully consider a funding strategy that is holistic and transdisciplinary in nature and deliberately designed to maximize the return on investment in a synergistic fashion, she said. For example, early rounds of funding could take advantage of the interdisaster period by supporting the development of tools to expedite comprehensive immediate postdisaster research (e.g., from a research capacity-building perspective, tools to accelerate field-ready protocols, predictive risk models, community-based participatory research, and environmental health literacy). Another urgent need, particularly suited for intramural exploration through a workshop, is to define, measure, and communicate about “exposure.” The yield of such interdisaster projects sets the stage for comprehensive human health research including inter- and transgenerational studies in future funding rounds.

Lichtveld concluded with a proposed paradigm for the Gulf Research Program based on science, policy, and practice (Figure 7-4). The Program could focus on the linkages among these three components through gap analysis and risk reduction, translation into applications, and implementation and monitoring.

CLIMATE CHANGE AND SEA LEVEL RISE

During the discussion period, several participants noted the anticipated impact that climate change and sea level rise will have on the Gulf region. Paul Sandifer noted that “[health and environmental] baselines will be affected by changing climate, so this should be an issue that cross-cuts the Gulf Research Program’s activities.” Cornelis Elferink, University of Texas Medical Branch, agreed, noting that “a 30-year period is probably long enough to start seeing those impacts in the most vulnerable coastal areas around the Gulf of Mexico.” Both remedial and preventive measures will be needed to deal with the problem, he said. Stegeman agreed,

Thirty years will be long enough. We’ll know a fair amount about the degree to which this will be a disaster in the making and how strong of a disaster it will be … If there is a 3-foot increase in the next 15, 20, 30 years, you’re going have to rebuild a lot of the coast. A lot of the infrastructure that you now live with will not be livable. There will be an accommodation to a slow and progressive change that will adversely impact all communities and all of the mental health and community resilience features that have been spoken about.

____________

2 See http://tulane.edu/cps/students/servicelearningcourses.cfm.

FIGURE 7-4 A possible paradigm for the Gulf Research Program would be to mediate the linkages among science, policy, and practice. SOURCE: Presented by Maureen Lichtveld on September 24, 2014.

The remarks of the presenters in the final panel led to an extended discussion of community engagement, which also came up many other times in the workshop.

As Lichtveld pointed out, community engagement can mean different things. To inform is to provide balanced and objective information. To consult is to obtain feedback on analysis, alternatives, and/or decisions. To involve is to work with the public to understand and consider issues and concerns. To collaborate is to work together to develop alternatives and identify solutions. And to empower is to place the final decision in the hands of the public. All of these approaches require funding, she observed, and this funding needs to be in hand before rather than after a disaster if it is to be fully effective in building sustainable community–academic partnerships.

Bernard Goldstein, University of Pittsburgh, pointed to a similar three-tiered approach to community engagement. One level is letting the community know before they read in the newspapers about research results derived from the community. A second level is hiring community people and setting up community advisory committees to help with the research. And a third level is meaningful community involvement in setting the research agenda. This takes a lot of time to develop relationships with community members, he said, especially because it needs to be done before a disaster occurs rather than after a disaster strikes.

Sharon Gauthé, executive director of Bayou Interfaith Shared Community Organizing in Louisiana, argued for the most inclusive option possible, treating communities as “a partner rather than as a subject.” When they are partners rather than subjects, communities can identify the gatekeepers in a community. “What we know, we want to share,” she said. “We want to be considered as equal partners in addressing the situation, and we want to learn and teach all of our community how to be successful.” Along those lines, Kim Anderson, Oregon State University, noted that she had sometimes worked with communities that owned the data generated in a research project, rather than having the data reside solely with a research team (Harding et al., 2012).

As Lynn Goldman and others pointed out, disaster research has shown that people who are more recently arrived in a community are the least likely to understand the things that need to be done in the case of disaster. Many communities around the Gulf Coast are relatively new and filled with people who have not lived in the area a long time, along with “snowbirds” who live in the Gulf region for just part of each year.

Several participants, pointed to the need for research that demonstrates the value of community engagement. “We need data to show how outcomes from disasters are better if people participate in the development of plans and other policy documents,” said Jennifer Horney, Texas A&M University. Aubrey Miller, NIEHS, raised the possibility of conducting research to understand the effect of participation in a participatory research program on a community’s response to a disaster. This is critical to understand, he said, but it is not currently studied using systematized or standardized approaches.

Finally, LaDon Swann, Mississippi-Alabama Sea Grant Consortium, referenced a seven-part test developed by the Kellogg Commission on the Future of State and Land-Grant Universities (Kellogg Commission, 2001) and noted that “understanding engagement isn’t that difficult for those who work with it on a daily basis,” such as those engaged in extension programs. These programs are always concerned about workforce development within the water-dependent industries they serve, which provides an important leveraging opportunity for the Gulf Research Program.

At many points during the workshop, several participants highlighted the need to develop cross-sector leaders who are able to address complex issues at the intersection of health and the environment.

Paul Sandifer underscored the need for a long-term investment strategy to develop academic leaders, who are “much more capable than most of us have been, in working across disciplines.” Linda McCauley, Emory University, observed that such leadership and education development programs need to be linked to research funding. “We have the responsibility to provide a funding pathway that can support trained individuals to do this work after they graduate,” she said. The Gulf Research Program cannot encourage individuals to think across boundaries but expect them to obtain funding from agencies that have specific missions, she said.

Several workshop participants emphasized the need for researchers to engage policy makers as well as communities. Maintaining a connection between research and policy makers makes it more likely that research recommendations will be implemented. And, as with communities, such engagement can transform outreach to dialogue. Linda Usdin, of SwampLily, suggested the need to better understand the process of decision making and how to include community members in ways that are meaningful. “I think we all know that policy makers, politicians, and community members can have the best information available.” But it is having the tools to make sure that information is used in decision making that matters.

Several participants suggested the creation of a leadership academy in the Gulf region to support cross-boundary education, training, and interactions for academics, policy makers, and community members. Michael Blum, Tulane University, noted that there are models of disaster resilience leadership academies, but that they are generally focused on educating policy makers; the Gulf Research Program could build upon these models and develop a curriculum that could be extended to a broader constituency.

Several participants also discussed the need to think about how to sustain the Program over the long term. Stegeman observed that the Gulf Research Program has the opportunity to put something in place that will help communities rebound successfully from disasters. However, he observed, the need for resiliency is more than a 30-year problem, and the Gulf Research Program needs to also begin to put things in place to ensure that the important aspects of the program can be sustained after 30 years. Stegeman also challenged the audience to think more broadly: “Can we develop something that enhances human health and the environment in the Gulf that also pertains to other communities, national and globally? Let’s figure out how to do research that creates something that is of lasting importance, well beyond 30 years.”