Highlights from the Speaker’s Presentation*

- An equitable society is one in which all people can participate and prosper. Achieving equity requires intentionality, focus, and a commitment to community participation.

- Achieving equity also requires concentrating resources in the places of greatest need.

- An explicit focus on the issue of health equity when drafting policy, practicing solutions, and developing research agendas and policy options can help organizations make progress on the issue.

- Programs that involve people from the community in decision-making roles have the most impact in achieving their goals.

______________

*Highlights identified during the presentation and discussions attributed to Mildred Thompson of PolicyLink.

Health is not just the absence of illness but an overall state of physical, economic, social, and spiritual well-being, said Mildred Thompson, director of the Center for Health Equity and Place at PolicyLink, a national research and action institute working for economic and social equity (WHO, 1948). This definition has a critical influence in the context of health equity.

PolicyLink defines equity as just and fair inclusion for all. An equitable

society is one in which all people can participate and prosper, said Thompson. In turn, achieving equity requires intentionality, focus, and a commitment to community participation.

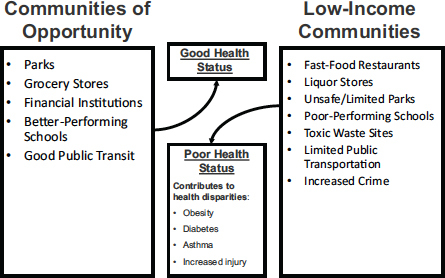

The contrast between communities of opportunity and low-income communities demonstrates the ways in which inequity comes into play in America (see Figure 2-1). Communities of opportunity have parks, good grocery stores, financial institutions, better-performing schools, and good public transit, explained Thompson. Low-income communities, by contrast, have fast-food restaurants, liquor stores, unsafe or limited parks, toxic waste sites, limited public transportation, and increased crime. These attributes of low-income communities contribute to health disparities in such areas as obesity, diabetes, asthma, and rates of injury, Thompson observed.

Schools are a prime example of the differences between communities of opportunity and low-income communities. In communities of opportunity, well-performing schools offer advanced placement courses to their students so they are ready for college. In low-income communities, many schools do not even offer advanced placement classes. Thus, when students get As in their courses, they think they are ready for college, but they later real-

FIGURE 2-1 For communities, an abundance or lack of opportunities and income plays a direct role in influencing health outcomes. Differences in opportunities and income result in health inequities.

SOURCE: Thompson, 2014. Reprinted with permission.

ize that they are underprepared. “It’s not because they are not smart; it’s because they didn’t have opportunities provided to them,” said Thompson.

Not all residents in communities of opportunity have good health. But they have better opportunities to be healthy, Thompson suggested, while those who do not have such opportunities tend to be at greater risk for poor health. Furthermore, when those in low-income communities are provided with such opportunities, everyone benefits. For example, the Harlem Children’s Zone, which has been expanded to a large-scale federally funded initiative known as Promise Neighborhoods,1 is premised on the belief that all children can do well, Thompson noted. An emphasis of this initiative is that all children deserve equal opportunities to lead healthy lives, graduate from high school, and have economic opportunities throughout their lives, regardless of the zip code in which they live. “If you go on the website and you read about Harlem Children’s Zone,” said Thompson, “you will see the remarkable number of kids who are going to college, because there was someone who really believed in them and had a vision of how to make that real.”

Disparities in opportunity show up clearly in national statistics on obesity, Thompson noted. Today, 22.0 percent of all U.S. children live in poverty, but the percentages are 35.0 percent and 38.2 percent for Latino and African American children, respectively, compared with 12.4 percent for non-Hispanic white children. These percentages, suggested Thompson, reflect a relative lack of opportunity for populations of color (DeNavas-Walt et al., 2011). At the same time, 20.2 and 22.4 percent of African American and Latino children and adolescents, respectively, are obese, compared with 14.1 percent of white children and adolescents. These same differences by population group can be seen in adults: 47.8 percent of African American, 42.5 percent of Latino, 32.6 percent of white, and 10.8 percent of Asian American adults are obese (Ogden et al., 2014). Furthermore, the gaps among these population groups have been growing over time (Trust for America’s Health and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2014).

Inequities also exist geographically. The physical inactivity rate for all adults in the United States is 25.4 percent, while Mississippi and Tennessee have the highest rates of inactivity at 36.0 percent and 35.1 percent, respectively. At the other end of the spectrum, the physical inactivity rate is 19.1 and 18.9 percent in California and Utah, respectively (CDC, 2014). By

____________________

1Promise Neighborhoods is a U.S. Department of Education program that intends to improve educational outcomes for students in distressed urban, rural, and tribal communities. The program funds nonprofit organizations and higher education institutions to design comprehensive community programs and “cradle-to-career” services. PolicyLink assists communities participating in the program through its Promise Neighborhoods Institute. More information can be found at http://www.promiseneighborhoodsinstitute.org and http://www2.ed.gov/programs/promiseneighborhoods/index.html.

looking more closely at population segments, said Thompson, it becomes clear that population-level data can mask underlying inequities. Achieving greater equity, she suggested, means that “we have to concentrate resources in the places that have the highest incidences of these issues.”

INSTITUTIONAL APPROACHES TO CREATING HEALTH EQUITY IN A CHANGING U.S. POPULATION

Reducing inequities requires changing the environment, said Thompson. More than 20 years ago, she began working with the Oakland Healthy Start Program to reduce infant mortality. “We realized back then, in the 1990s, that the condition of infant mortality was not going to be solved by just having more clinicians, by just extending the clinic hours. We did all of those things, but what was really clear was that we [had] to change the environment in which those babies were dying.”

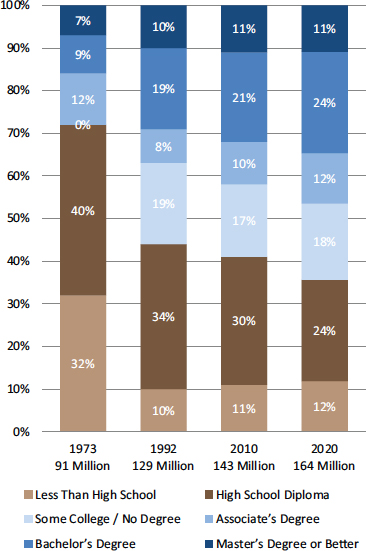

Many of the communities that have high infant mortality rates also have high rates of obesity, diabetes, and crime. The consequences for the children growing up in those communities are dire, said Thompson: “Our children are not getting the kind of attention that they need in order to thrive and to be the future leaders that we need for them to be.” As an example, she returned to education. Most new jobs require education beyond high school (see Figure 2-2). “We have to make sure that we are training and preparing our students to meet those needs,” Thompson said.

By 2040, the majority of the U.S. population will be made up of people of color. This is already the case in four states: California, Hawaii, New Mexico, and Texas (U.S. Census Bureau, 2013). If the children in these population groups are not being prepared for the future, the future will suffer, Thompson said. If the future workforce lacks the education needed for the available jobs, the result will be poor economic outcomes not only for people with low educational attainment but also for businesses and employers that lack adequately skilled workers, she noted.

PolicyLink has been studying institutions and organizations across the United States that are working on issues of health equity, asking about their work, their funding, their outcomes, and their partners. For example, some progressive public health departments have been going well beyond their mandates. “What we’re learning from them is how they have been able to change those institutions to address health equity,” said Thompson. This research has led to several observations about what works:

- inserting goals for achieving health equity into policies, programs, and practices;

- focusing on race and place in crafting policy and practice solutions;

FIGURE 2-2 Jobs in the United States require increasingly high levels of education.

SOURCE: Carnevale et al., 2013. Reprinted with permission from the Georgetown Center on Education and the Workforce.

- acknowledging health equity when developing research agenda and policy options; and

- supporting the creation of institutes or centers with a focus on specific health equity outcomes.

The challenge in practice, said Thompson, is how to make such changes happen.

Thompson offered several questions for organizations to consider when undertaking the necessary changes in addressing health equity related to race, ethnicity, and economic status.

First, in the area of data collection and analysis:

- What indicators are you using to better understand health inequities in your communities?

- Who is most impacted by these inequities? Where are these inequities the most severe?

In the area of strategy development:

- What equity outcomes are you seeking to achieve through the proposed strategy?

- Who is intended to benefit from this strategy?

- How will this strategy benefit low-income communities and communities of color?

- How does this action help to achieve greater racial and economic equity?

- What organizational practices may create barriers to achieving racial and economic equity?

Finally, in the area of community engagement:

- How are those most impacted by inequities involved in your initiatives?

- What opportunities are you creating to have community members actively participate?

Expanding on this final area as an example of how to move forward, Thompson noted that consensus exists on the value of community engagement, but the challenge lies in engaging communities in a substantive way.

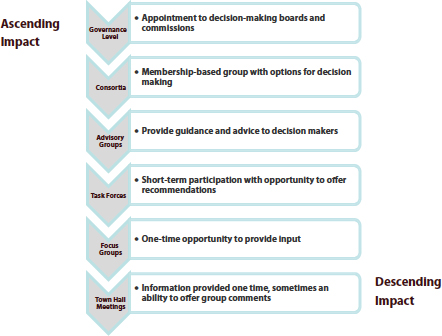

FIGURE 2-3 The community can be engaged at different levels with different impacts.

SOURCE: Thompson, 2014. Reprinted with permission.

Community engagement has different levels with different impacts (see Figure 2-3). According to research with which Thompson has been involved at PolicyLink, programs that incorporate governance-level involvement, meaning that people from the community are in decision-making roles, have the most impact in achieving their goals. “All involvement is not equal,” Thompson said. However, community engagement also requires capacity building, so that community members will have the skills and the opportunities to understand the need to focus on racial and economic equity.

“How do you create an environment where everyone’s voice is valid?” Thompson asked. “It’s up to us to create an environment that is open and receptive so that we all see each other as having as much value and contribution as everybody else.”

A variety of programs are demonstrating what can be achieved, Thompson observed. For example, the Healthy Food Financing Initiative

and California FreshWorks Fund have established “a wonderful example of cross-team collaboration and public–private partnerships.” California FreshWorks Fund addresses equity by targeting its resources to communities that experience low access to healthy foods because of the market-based assumption that poor communities do not have adequate resources to support a grocery store. With seed money from The California Endowment that leveraged additional financing—including both investments in the fund of as little as $20 by individuals and private-sector contributions from Chase Bank and Bank of America—the FreshWorks Fund has raised more than $250 million (California FreshWorks Fund, 2014). As examples of the steps being taken by these and other organizations to promote place-based approaches to equity through local action, Thompson cited:

- working with neighborhood corner stores in those communities experiencing health inequities to help them adopt and sell healthier products while remaining profitable;

- increasing farmers’ markets;

- linking farmers to consumers through such measures as urban agriculture, community-supported agriculture, and community gardens;

- establishing stronger nutrition standards in schools; and

- increasing the number of grocery stores in low-income communities.

Thompson also described a policy strategy developed by Kaiser Permanente known as Exercise as a Vital Sign (EVS) (Sallis, 2011). To monitor, measure, and improve activity levels, Kaiser health care providers in 2009 began asking patients two questions:

- How many days per week do you engage in moderate to strenuous exercise (like a brisk walk)?

- On average, how many minutes per day do you exercise at this level?

EVS has become a basis for ongoing conversations about patients’ exercise habits, Thompson said. Asking these questions has motivated patients to want to be healthier and make a difference in their own health care. These conversations provide encouragement and can result in referrals to such activities as Zumba classes, yoga, hiking clubs, and other community resources. Most important, Thompson noted that a 2014 study found that asking patients about their exercise habits was associated with modest weight loss in overweight patients and some improved glucose control among diabetics (Grant et al., 2014).

Thompson drew several lessons from her overview of health equity issues.

First, framing is important. For example, work on health equity has to focus not on the individual but on the environment, she said—“less blaming the victim and [more] figuring out what the things are in the environment that must be changed.”

Second, partnerships matter. Businesses, funders, governments, and communities all have roles to play.

Third, the context needs to be understood. “When is it going to be productive to introduce a new idea? When do you involve partners? When can you move a strategy forward? It’s all based on the environmental context.”

Fourth, assessment is critical. “We have to continually figure out how we are monitoring our work and doing things differently.”

Fifth, capacity needs to be built continually, not only within the environment but also among staff and partners.

Finally, “how do we tell our story in our own way?” Those working on health equity need to control the narrative and not leave that to others, Thompson said.

As an example of how these lessons can be applied, Thompson described the evaluation of the Healthy Eating, Active Communities initiative (Samuels & Associates and The California Endowment, 2010). This place-based initiative helped six low-income communities approach environmental and policy changes and build health equity. These steps included

- adopting new physical education curricula to improve the quality of physical education classes;

- implementing teacher training to maximize adherence to state standards;

- adopting physical activity standards in after-school programs to improve the quality and quantity of physical activity;

- advocating for park development, maintenance, or improvement, thus creating safe and appealing spaces for physical activity; and

- instituting pedestrian safety improvements—installing traffic signals, employing crossing guards, establishing walking clubs, and creating safe walking paths between residential areas and schools—to encourage walking to and from school in all sites under the Healthy Eating, Active Communities program in California.

“We saw major changes happen as a result of these strategies that were put in place across the state of California,” Thompson said.

Finally, Thompson listed a number of ingredients for success in working for health equity:

- strong, sustained leadership;

- commitment across sectors;

- bold risk takers who can think outside the box;

- equity-focused strategies;

- creative, compelling use of data;

- government–community partnerships;

- adequate resources;

- long-term involvement; and

- continuous assessment of impact and modifications as needed.

The programs that have the greatest impact all have, to some degree, these elements of success, Thompson said. Furthermore, success requires humility: if we all acknowledge that we do not know everything and are open to continuously learning, everyone benefits. When a community says a particular approach is not working, programs need to be willing and able to adjust.

“I’m somewhat optimistic that the [obesity] crisis is solvable, but I’m also worried. I think in the population that is aware and has resources, we can probably solve this crisis in the near term. But what I’m worried about is that in the high-risk populations or the socially disadvantaged populations—which include many ethnic minority populations and people in disadvantaged communities—the [obesity crisis] will either get worse, or it won’t get any better. This means that the disparity between the advantaged and the disadvantaged groups will increase. That’s the part I’m worried about. We need some very deliberate solutions to make sure that we [address] why the rates are higher in certain populations.”

—Shiriki Kumanyika of the University of Pennsylvania