8

PLACE MATTERS: Building People Power to Tackle Fundamental Causes of Obesity in Cook County, Illinois1

Highlights from the Presentations of Individual Speakers*

- Cook County PLACE MATTERS (CCPM) addresses the interconnection of systems of food production, distribution, marketing, and consumption by combining research documenting the inequitable distribution of health risks and resources across communities with grassroots organizing and activism and policy analysis. (Bloyd)

- People who are affected by health inequities are often the experts in their own challenges and are the ones who can develop effective solutions to the inequities. (Tendick-Matesanz)

- CCPM works to build the capacity of leaders and communities to address social, economic, and environmental conditions that shape health inequities. (Bloyd)

- CCPM’s community partners include a labor organization that fights inequities in the food service industry, such as by advocating for paid sick days for low-wage restaurant workers (Tendick-Matesanz).

______________

*Highlights identified during the presentations and discussions; presenter(s) to whom statements are attributed are indicated in parentheses.

____________________

1See Appendix D for additional information.

Cook County, Illinois, is the focus of a cross-sector effort that entails advocating for food justice as an essential way to target the fundamental causes of obesity. The work there is one of 19 regional projects participating in PLACE MATTERS, a national initiative of the National Collaborative for Health Equity (NCHE), which connects research, policy analysis, and communications with on-the-ground activism to advance health equity (Christopher et al., 2010; see also the discussion of health equity in Chapter 2).

NCHE executive director Brian Smedley explained that the collaborative’s mission is to build the capacity of leaders and communities to address social, economic, and environmental conditions that shape health inequities. PLACE MATTERS’ 19 teams across the country are beginning to build political and public will for “policy and systems change that will address the heavy concentration of health risks that are too often found in highly segregated communities of color around the country,” he said.

Food justice, the focus of Cook County PLACE MATTERS (CCPM),2 is not just about what people put into their bodies, Smedley said; it is also about how the systems of food production, distribution, marketing, and consumption interconnect. The Cook County initiative combines research documenting the inequitable distribution of health risks and resources across communities with grassroots organizing and activism and insightful policy analysis to identify solutions.

Smedley introduced the panel of three speakers who shared their accounts of the Chicago-area case study: Jim Bloyd, leader of the CCPM team, who co-leads the community health improvement and planning process at the Cook County Department of Public Health; Felipe Tendick-Matesanz, programs coordinator at Restaurant Opportunities Centers (ROC) United in Chicago, which seeks to create a sustainable food economy; and Bonnie Rateree, a community advocate who leads the Human Action Community Organization in Harvey, Illinois, and is school board vice president for Public School District 147.

THE CONNECTIONS AMONG FOOD, NEIGHBORHOODS, AND HEALTH INEQUITIES IN COOK COUNTY

Bloyd described the CCPM vision: “to build a health equity movement that works to eliminate structural racism3 and creates the opportunity for

____________________

2For more information, see https://www.facebook.com/ccplacematters and youtube.com/ccplacematters.

3This workshop summary provides a brief discussion of structural racism, but a deeper treatment of the topic is available in the 2003 Institute of Medicine report Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care (IOM, 2003).

all people of Cook County, Illinois, to live healthy lives.” The main point of the program is that the roots of the obesity epidemic lie in poverty; structural racism; education; and unhealthy neighborhood and living conditions, including a lack of access to healthy food that disproportionately affects people of color. Bloyd’s team wants to address these barriers, he said.

The CCPM strategy is informed by the research of Adam Drewnowski, who has observed that while studies of obesity in the United States have steered clear of the complex issues of poverty and social class, the quality of people’s diets is reliably predicted by education, occupation, income, and other indices of social class (Drewnowski, 2012). Organizing “people power” against the greater influences of money and privilege is the way to enact healthy public policy, Bloyd said. CCPM does that by working with ROC United—which aims to address racial segregation and improve labor conditions for restaurant industry workers—and by building alliances with social justice champions such as Rateree.

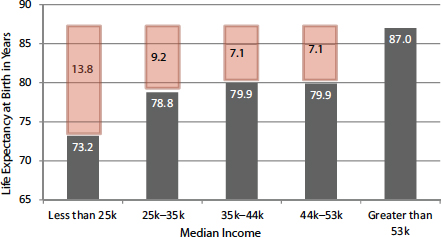

The program raises public awareness of health inequities through its newsletter, social media, and discussions of such films as the Unnatural Causes documentary series (California Newsreel, 2008). It also educates and builds relationships with policy makers such as Cook County board president Toni Preckwinkle. When CCPM released its 2012 report (Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies, 2012), Bloyd quoted Preckwinkle as commenting: “It is shameful that we live in one of the wealthiest countries in the world and that a person’s life can be cut short by more than a decade because of factors outside her or his control. People living in areas with a median income greater than $53,000 per year have a life expectancy that is almost 14 years longer than people living in areas with a median income below $25,000 per year” (see Figure 8-1). The CCPM report offers several recommendations, Bloyd said that sufficient funds be allocated to increase healthy food retail outlets in neighborhoods with low food access; that the voices and aspirations of neighborhood residents be reflected in solutions to hunger and poor nutrition; that workplace justice be ensured for workers throughout the food chain, including the restaurant industry; and that persistent poverty be addressed through the engagement of multiple sectors.

To illustrate how population demographics relate to income levels and diet, Bloyd noted that the child poverty rate in Harvey in south suburban Cook County—where two-thirds of residents are people of color—is 45.4 percent (Cook County Department of Public Health, 2008). That rate is six times greater than the rate in north suburban Cook County, where two-thirds of residents are white. Other data show that African American ninth graders in suburban Cook County reported eating less fruit, fewer green salads, and fewer carrots in the previous week compared with other racial groups (Cook County Department of Public Health, 2010).

FIGURE 8-1 Average life expectancy is lower for people who live in census tracts or municipalities in Cook County with lower median incomes. Life expectancy calculated by the Virginia Commonwealth University Center on Human Needs from 2003–2007 data provided by the Cook County Department of Public Health and the Chicago Department of Public Health; median income based on Geolytics Estimates Premium for 2009.

SOURCE: Adapted from Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies, 2012. Reprinted with permission.

Further evidence of how place matters to people’s living conditions is the dramatic effect of segregation in Metro Chicago: while 90 percent of poor white children live in low-poverty neighborhoods, about 75 percent of poor black children and 45 percent of poor Latino children are exposed to “the life-threatening environments of higher-poverty neighborhoods,” Bloyd said (Heller School for Social Policy and Management, 2011; IOM, 2008). He noted that this pattern “has some of its roots in the state-sponsored segregation of the 1930s Home Owners Loan Corporation” (California Newsreel, 2003; Jackson, 1980).

PROTECTING WORKERS IN THE FOOD SERVICE SECTOR

Tendick-Matesanz highlighted the social justice struggles of the 13 million workers who prepare, deliver, and serve the nation’s food in the restaurant industry. He hoped to “plant a little seed” to make listeners realize that “a lot of the conversation we have been having today is actually a human rights conversation, versus just a public health conversation.”

Tendick-Matesanz grew up in a family that owned a fine-dining restaurant and paid their employees relatively high wages, with sick days and benefits. In 2008, he co-founded ROC United, and since then he has been “building power with workers and addressing inequality and inequity in the food system.”

ROC United is the only national nonprofit dedicated to improving the wages and working conditions of U.S. restaurant workers. Its national worker center has more than 10,000 members. Its innovative approach to system change is based on research and policy, workplace justice, and promotion of the “high road” to profitability. “At our core is the human right to work with dignity,” Tendick-Matesanz said. “We provide this through building power and community organizing with workers, owners and entrepreneurs, and consumers to create what I like to call a shared prosperity outcome.”

The restaurant industry is one of the fastest-growing sectors of the U.S. economy and the country’s second-largest employer. Yet ROC United’s research has found that the industry has some of the nation’s lowest-paying jobs, with little access to benefits and career advancement. “Nearly 90 percent of workers do not receive paid sick days. And lower-wage positions within the industry are predominantly filled by women and people of color,” Tendick-Matesanz said.

Racial discrimination is widespread in the industry, Tendick-Matesanz noted: workers report being passed over for promotion because of their race, and employees of color are paid less than white employees (Restaurant Opportunities Centers United, 2014b). Other major problems include rampant labor violations, consistent failures to ensure occupational health and safety and public health, and wage stagnation (Restaurant Opportunities Centers United, 2010, 2011). The federal wage paid to tipped workers has been frozen since 1991. Although federal law requires employers to make up the difference between the tipped wage and the minimum wage, a U.S. Department of Labor investigation found that 84 percent of employers were noncompliant. Tipped workers live in poverty at three times the rate of the U.S. workforce, and 46 percent of them are single mothers (Restaurant Opportunities Centers United, 2014a).

To address such injustices, ROC United is tackling large players, including the Darden Company, which owns 13 brands, including the Olive Garden. “We have found consistently poor working conditions,” Tendick-Matesanz said. “We are putting a lot of pressure . . . to change the working conditions in the restaurants and then influence other players.”

Recently, ROC United helped a coalition pass the first law in Washington, DC, requiring paid sick days for restaurant workers. Paid sick days are “a very important and essential need for many of us if we are going to talk about health and health inequity,” Tendick-Matesanz pointed out.

FIGHTING FOR FOOD JUSTICE IN HARVEY, ILLINOIS

Rateree spoke about food justice issues facing the working poor of south suburban Cook County, where she has been active in cross-sector efforts involving partners ranging from her public school district and the county health department to Ingalls Hospital and the Harvey Community Center. She began by showing a photograph of a local playground for which she helped lay concrete. The playground was a collaborative project with KaBOOM! “We built the playground, we built the garden boxes, an outdoor classroom. . . . It is a wonderful experience to show what we can do when we collaborate.”

PLACE MATTERS research showed that Rateree’s community has suffered from discrimination through public policies and procedures, she said. Rateree is a school board member in the same school district where she was a student growing up. Between the time she was in kindergarten and the end of eighth grade, Rateree noted that the racial makeup of Harvey changed substantially, with African Americans increasing to 80 percent of the population (Cook County Department of Public Health, 2008). That shift changed how children were educated and provided with health care. “We stopped getting the quality education that we had before,” she recalled. “We stopped getting the funding because we [as a society] stopped caring about the children in the room.”

Those changes in education financing had consequences for school food, Rateree pointed out. She tries to teach students to plant their own gardens and eat more fruits and vegetables, but as a school board member, decision maker, and leader, she can only give the children what she can financially afford. Her neighborhood is a place where people “get the least amount of money for education,” a fact that dictates the school breakfast and lunch programs. Research by Ralph Martire at the Center for Tax and Budget Accountability shows that Illinois ranks 50th among states in the portion of public education funding covered by the state rather than by local resources, Rateree noted (Center for Tax and Budget Accountability, 2013).

Talking about race with a group such as the workshop attendees can be uncomfortable, Rateree said. Such talk “very often shuts you down,” she told them. “You do not want to talk about it. We often do not want to think about it. It is that ugly part of our history that we wish would just go away. But today we use geography to continue this unequal system that causes obesity, chronic diseases, and early death. Food deserts exist in a neighborhood where grocery stores and community gardens used to stand.”

Teaching children to grow gardens motivates them to eat healthfully, Rateree said. But it also teaches the importance of nutrition, the sciences, mathematics, and character development while exposing them to potential

future career opportunities in health and nutrition. Education is a right. Yet the laws, policies, and procedures in the United States have historically and to this day denied people of color their human rights, Rateree said. She ended with a plea: “I am asking you, all of you who are here who are in any policy-making positions . . . please realize that what these communities need more than anything else is the same resources you have in yours.”

During the discussion period, Smedley asked the CCPM speakers how they began the conversations with each other to connect across sectors. What did it take to help them come to the same table and then continue to work together?

The process was gradual, Bloyd recalled. He and his colleagues had been interested in looking at nutrition, food systems, and food justice and were excited to promote the Healthy Food Financing Initiative in Illinois. In the course of that work, he met Rateree because of her activities in organizing community gardens and a farmers’ market in Harvey. Meanwhile, CCPM’s steering committee had observed that labor in the food system often was absent from discussions about healthy food, but recognized that the people who produce and harvest food and who cook, prepare, and serve it to customers in restaurants “need to have the same ability to feed themselves and their family nutritious foods,” Bloyd said. So CCPM decided to pursue collaborations with labor, and ROC United was a perfect partner.

For his part, Tendick-Matesanz added that the CCPM partners all came from a “core of building together and from the ground up,” looking for new approaches to accomplishing change. They often talk about how to foster decision making on the ground for those who are affected, especially since “people who are affected are often the experts in their own challenges.” Building relationships “is easy,” Tendick-Matesanz said. “Just go into the community and ask them what they need . . . and they will come up with the solutions.”

“The great thing is that all of those different goals have convergent interests, convergent strategies, and that’s where the real juice is.”

—Loel S. Solomon of Kaiser Permanente

This page intentionally left blank.