10

Community Transformation in the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians in Michigan1

Highlights from the Presentations of Individual Speakers*

- The Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians’ (Sault Tribe) Community Transformation initiative has been strategically expanding and building upon successful cross-cutting strategies to improve health and reduce disparities among communities of Sault Tribe members living in the Sault Tribe service area of Michigan’s eastern Upper Peninsula. (Norkoli)

- A collaborative and participatory approach has helped engage and bring change across tribal and nontribal sectors. (Laing)

- A participatory, respectful, and culturally sensitive approach to data collection was key to earning the Sault Tribe leadership’s cooperation in sharing the community’s health assessment information. (Laing)

- Population health survey data are enabling the tribe to tailor its strategies and planning, such as its efforts to target obesity in schools and early childhood programs. (Laing)

______________

*Highlights identified during the presentations and discussions; presenters to whom statements are attributed are indicated in parentheses.

____________________

1See Appendix F for additional information.

The eastern half of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan is an 8,500-square-mile region sparsely populated by 179,000 residents. Roughly 14,000 of them are members of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians (Sault Tribe) who live in communities across the region rather than in a reservation area. For the past decade, tribal leaders have been working on a cross-sector initiative aimed at reducing the high rates of obesity and other health disparities in the tribe’s service area. The workshop participants heard a description of this initiative from Donna Norkoli, project coordinator for the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe’s Community Transformation Grant; Shannon Laing, program coordinator for tribal health and wellness in the Center for Healthy Communities at the Michigan Public Health Institute; and Sault Tribe planning and development director, Jeff Holt, who also chairs the Sault Ste. Marie Economic and Development Commission.

LEVERAGING GRANT DOLLARS ACROSS SECTORS FOR HEALTHIER, SAFER COMMUNITIES

Norkoli summarized the history of the Sault Tribe Community Transformation Grant (STCTG) initiative.2 Its lead convening agency, the Sault Tribe Community Health Department, began a project in 2006 in Sault Ste. Marie with a small grant from the Steps to a Healthier Anishinaabe Project. In 2008 this work was broadened to include the communities of Munising, Manistique, and St. Ignace with funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as part of the Strategic Alliance for Health Project. In 2011 the tribe obtained a Community Transformation Grant allowing it to expand the work further into Kinross and Newberry. Since then, the initiative has partnered with other existing coalitions and partners to promote shared goals in communities across the entire seven-county service area.

The initiative is overseen by a tribal leadership team of decision makers who are instrumental in bringing policy, systems, and environmental changes to the tribal agencies where they work. Represented sectors include health, housing, transportation, economic development, enterprise (including casinos), early childhood, and youth education and activities. Among the challenges to be overcome are the broad geographic area and small population numbers, Norkoli said—as well as winters with a great deal of snow.

Norkoli highlighted three successful STCTG coalition-building strategies. The first entailed creating relationships with local public schools (because the tribe does not have its own schools). “When we first started this work, the tribe was kind of in isolation,” Norkoli said. “The schools were in their own little silo, and local government worked on its own.

____________________

2For more information, see the STCTG website at http://www.up4health.org.

Nobody really was collaborating, especially with the tribe.” With funding in hand, the tribe organizers cautiously approached the local schools. “We were very careful not to say ‘we would like you to improve your school lunches,’ or ‘we would like you to offer more [physical education] time,’” Norkoli said. Rather, the tribe offered some funding to help the schools build capacity and infrastructure to form coordinated school health teams and conduct assessments of their environments. The schools could create an action plan and tell the tribe what they wanted to do, Norkoli said. “We wanted to make sure that they owned the project.” Five schools went on to develop action plans that included participating in the Safe Routes to School project, which aims to increase students’ physical activity and get them walking and biking to school. The STCTG initiative has worked with 17 school districts across the region to implement some form of coordinated school health.

A second strategy involved approaching local governments on transportation issues. A major problem was that the largest employers of tribal members are casinos, but those businesses are connected to tribal housing sites and health centers only via “dangerous highways with a lot of fast-moving traffic,” said Norkoli. The collaboration brought the tribal transportation planner together with city engineers, downtown development authority directors, and other stakeholders to look at transportation infrastructure, conduct walking audits and workshops, and create a nonmotorized transportation plan covering the seven-county service area. “A vision was created not just about increasing physical activity but how we could make walkable, bikeable, vibrant communities,” a move that local governments saw as offering economic advantages, Norkoli said.

That success also led to partnerships with the Village of Newberry and the city of Manistique to promote healthy eating. The tribe started two farmers’ markets in those communities and then added two others in smaller communities.

Norkoli and her colleagues worked hard to build sustainability into these efforts. Through workshops with the local governments, they worked to educate seven communities about the benefits of “complete streets” policies of the National Complete Streets Coalition in making streets safer and friendlier to pedestrians and bicyclists. The tribe provided some funding to local government agencies in implementing those policies by collaboratively creating nonmotorized transportation plans. For example, when the Sault Tribe gave one community $3,000, the village council matched the funding, drew up the transportation plan, and then used it to apply for additional state funding to put the plan into action. “That leveraged $230,000 for construction of sidewalks and shared-use paths and for the school to do some encouragement, education, and enforcement activities to promote walking and biking to school,” Norkoli said. The local public school and the village

used the funds to install a sidewalk and a crosswalk so that students could get to class safely.

During the discussion, panel facilitator Amelie Ramirez of the University of Texas in San Antonio asked about STCTG’s future plans for expanding or scaling up. Norkoli said the organizers hope to expand their work into some of the more western areas of the service region. In addition, the Sault Tribe recently extended its work on improving nutrition and physical activity at tribal early childhood education sites to nontribal sites across the region through partnerships with Great Start Collaboratives.

BUILDING TRUST WITH TRIBAL LEADERSHIP TO MEASURE COMMUNITY HEALTH

Laing described how she and her colleagues have worked systematically to improve the way in which community assessment data are gathered. She leads the evaluation team that is tracking outcomes of the STCTG initiative.

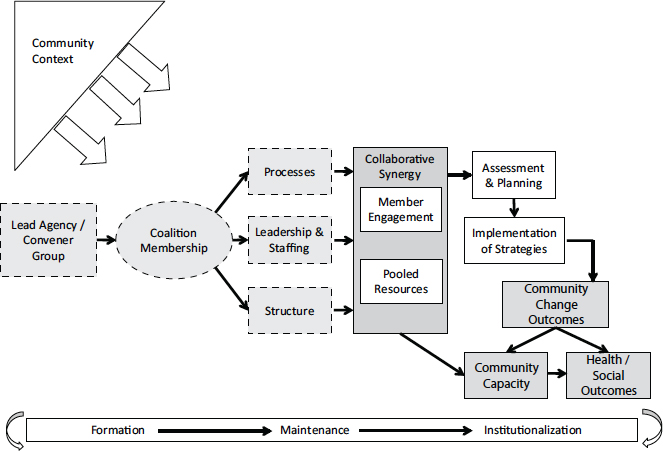

Laing explained that STCTG is based on the community coalition action theory model (Butterfoss and Kegler, 2002), in which “there is significant effort invested in coalition building over the life span of the work” (see Figure 10-1). Dedicated employees work to recruit and mobilize community members, help establish infrastructure in local communities and build their capacity, plan and implement strategic plans, evaluate outcomes, and support the ongoing institutionalization of strategies.

“The community context is very important,” Laing emphasized. For the Sault Tribe, contextual factors that have heavily influenced the successes and challenges of the STCTG initiative include the sociocultural and political environment, the local geography history, social norms, and the broader history that American Indians have experienced in the United States.

Essential to success, Laing said, has been the process of “putting data into action”—the collection, interpretation, and prioritization of data and their dissemination and translation into strategies. However, organizers initially faced many significant barriers to carrying out this process, such as the lack of reliable population-level data for obesity-related measures in the Sault Tribe. Available data showed wide disparities in the tribal community’s overall health as compared with the state population, “but what we didn’t know was whether disparities existed within the tribal population,” Laing said. “We were afraid that health inequities could continue to exist, or could worsen, if we couldn’t measure and monitor disparities with reliability and precision.” However, she also noted that “sharing data can be difficult for tribes because data has historically been misused, misconstrued, or misrepresented.” Thus, determining how to approach data collection for health indicators was critical; a participatory and respectful approach was key.

FIGURE 10-1 Community coalition action theory builds on the synergy of cross-sector collaboration.

SOURCE: Butterfoss and Kegler, 2002. Reproduced with permission of John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, in the format republished in a book via Copyright Clearance Center.

Since 2008, more than 100 assessment tools in different sectors across the service area have shown positive increases in measures of the physical, built, and food environments. These data were integral to a participatory prioritization and action planning process that local coalitions have used on an annual basis, Laing said.

In 2013, the Sault Tribe completed a population health survey. This survey provided data that will allow the communities to tailor their strategies in a targeted way. The survey results showed that rural areas and urban “clusters” differ in their adult obesity rates, physical activity levels, and consumption of fruits and vegetables. The survey also provided representative data for the first time on tribal children’s daily physical activity; screen time; and consumption of produce, junk food, and sugary beverages. This information is enabling the tribe to conduct long-term planning for obesity prevention by targeting modifiable factors in schools and early childhood programs, Laing said.

A key achievement has been the ongoing support of the tribal leadership for measurement and evaluation efforts “when protections are put in place, when the work is done in a culturally sensitive way,” Laing emphasized. In an unusual move, the Tribal Board unanimously approved a resolution that allows for the sharing of tribal health data to support the project’s goals.

Core elements of STCTG that have been essential to its success include a strong cross-sectional leadership team, with champions who are “willing to stick their neck out to reach across sectors, to create those linkages, to build this synergy,” Laing said. Also important has been carrying out well-designed and culturally sensitive assessment and formative evaluation activities on an ongoing basis, early and often. Good evaluation is necessary for strategic planning, Laing said.

To scale up and extend this work requires building community capacity, Laing noted. Dedicated, experienced staff who can provide technical expertise, support, guidance, and resources to help communities establish their own infrastructure and local leadership are crucial. Coaching and mentoring of these local teams are critical as well “to ensure that the early successes help build momentum and also long-term sustainability,” Laing said.

TAKING A SEAT AT THE DECISION-MAKING TABLE

Holt offered a perspective on STCTG from the tribal Leadership Team, which he said has provided an essential connection to the communities in working across sectors and serving as a conduit for communication. One barrier that the initiative encountered involved “turf issues” across sectors. For example, Holt explained, “Leaders of one sector may ask, Why is health involved to lead a business or a transportation issue?” STCTG organizers learned that “it is important to engage all the partners in assessments, prioritization of needs, and decisions about what and how best to carry out the strategies and to address identified needs,” Holt said. A collaborative process creates greater buy-in and commitment over the long term.

Other barriers included the usual red tape and limited resources of local governments. To break down those barriers, STCTG focused on taking its resources straight to key players to gain their support for creating action teams within their agencies, Holt said.

A driving motivation for the initiative was that in the past, the Sault Tribe often “did not have a seat at the table in a lot of the local communities,” Holt said. Its needs were not being met, and not enough open communication and trust existed between tribal and nontribal entities. But the situation is different now. Whereas for many years the tribe lacked the budget to maintain staff in key positions, the federal community health grants made it possible to hire a grants project coordinator and four local community coordinators; around the same time, the tribe hired a transpor-

tation planner. The tribe worked to create formal agreements with local governments, and tribal members provided more input for local decision-making processes by serving on committees and advisory boards. “Now that we are at the table, we can afford to speak up, and we are not afraid to,” Holt said.

A decade ago, Holt observed, Sault Tribe leaders were the ones going to nontribal communities asking for help. Now the tribe itself can offer assistance, expertise, and leadership: “When we go into a community, we now expect the communities to collaborate with us,” he said.

“No one entity has the resources to invest in a singular type of way to address the issue. No one. And so with that, everybody has to come together on this issue. It is solvable. It is solvable. It’s complex, but it’s solvable, and I believe that.”

—Yvonne Cook of Highmark, Inc.

This page intentionally left blank.