2

National Flood Insurance Program History and Objectives

This chapter begins with discussion of the history leading up to the 1968 legislation that created the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP). It is important to recognize that the original concept for the NFIP was a risk-sharing partnership with the private sector. With this history as background, this chapter discusses the enabling NFIP legislation and specific financial roles for the NFIP in the partnership. The changing nature of that partnership helps explain the motivation for provisions in BW 2012 and Homeowners Flood Insurance Affordability Act of 2014 (HFIAA, 2014).

INITIAL PROPOSALS FOR A NATIONAL PROGRAM OF FLOOD INSURANCE

Flood insurance was offered by private insurers between 1895 and 1927, but losses incurred from the 1927 Mississippi River floods and additional flood losses in 1928 led insurers to stop offering flood policies (Brown and Halek, 2010). In the absence of private insurance, post-flood financial aid took the form of flood disaster relief. Over time, the federal government was increasingly asked to provide aid to flood victims as a humanitarian action (Moss, 1999). It was in that context that President Truman proposed a national program of flood insurance. Initially, when requesting aid to victims of Midwest floods in 1951, Truman also asked Congress to “establish a national system of flood disaster insurance” (Truman, 1951a). Truman conceived of a flood insurance program “based upon private insurance with reinsurance by the Government,” and if such insurance were available,

“there should be no need in the future for a program of partial indemnities” (Truman, 1951a). Truman submitted draft legislation to Congress in 1952 that envisioned a central role for the private sector, noting that the program “should not compete with private insurance companies” and furthermore, the proposed legislation prohibited federal flood insurance where it was available privately at “reasonable rates” (Truman, 1952). Congress could create a reinsurance fund to “. . . make it possible for private companies to write flood insurance at reasonable rates” (Truman, 1951b) and he noted that rates could be lowered by a “nationwide pooling system” (Truman, 1951b). The proposed bill also put a cap on coverage and hence premiums, imposed a 10 percent deductible, and authorized federal agencies that guaranteed mortgage loans to require the purchase of flood insurance. Thus, as originally conceived, a federal program for flood insurance was designed to replace disaster aid and make private sector insurance more affordable by capping rates, pooling risks geographically, and offering reinsurance to private companies. However, no legislation was passed.

After the 1955 hurricane season, President Eisenhower proposed the creation of an “indemnity and reinsurance program, under which the financial burden resulting from flood damage would be carried jointly by the individuals protected, the States, and the Federal Government” (American Institutes for Research, 2005). That wording suggests that Eisenhower was especially interested in homeowners sharing future disaster aid costs with the government. Congress responded by passing the Federal Flood Insurance Act of 1956, which created the Federal Flood Indemnity Administration and established a flood insurance program, a reinsurance program, and a loan contract program. In 1957, specific implementation proposals were put before Congress, but Congress found them impractical and did not appropriate any funds. The Federal Flood Indemnity Administration was terminated on July 1, 1957.

Following Hurricane Betsy in 1965, Congress passed the Southeast Hurricane Disaster Relief Act. President Johnson pointed out that it was the “sixth law passed in 18 months for the specific purpose of broadening Federal aids for the victims of the unusually severe succession of disasters experienced since the spring of 1964” (Knowles and Kunreuther, 2014). In addition to relief, Congress called for “immediate initiation of a study . . . of alternative permanent programs which could be established to help provide financial assistance in the future to those suffering property losses in floods and other natural disasters, including but not limited to disaster insurance or reinsurance” (Knowles and Kunreuther, 2014).

In August 1966, President Johnson transmitted a task force report to Congress that was to set the stage for broad reforms to the federal role in flood risk management. The task force’s report, A Unified National Program for Managing Flood Losses, described multiple strategies for

managing flood risks. One section addressed “. . . steps toward a national program for flood insurance” and concluded that flood insurance was “feasible” and could “promote the public interest” and could be used both to help victims bear the risk of floods, and discourage “unwise occupancy of flood-prone areas.” Other subjects of reform included improving knowledge about flood hazards, coordination and planning for new development in floodplains, technical services to floodplain managers, and adjustment of flood control policy based on “sound criteria” (Task Force on Federal Flood Control Policy, 1966).

The report argued that the choice to locate in a floodplain might be an individual choice, and that those who chose to locate in floodplains should understand the risk and bear the full costs of their decision.1 That sentiment was endorsed and elaborated upon in a report from the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) issued in the same year. That report stated the following:

If the new occupant of such areas bears the full cost of flood insurance premiums, then he has to balance up the advantages and the costs of such occupancy. In some circumstances, it may be economic to occupy an area with relatively high hazard of flood damage, because the advantages more than offset the unavoidable costs. This may often be true for summer homes along the coast. . . . In many situations, however, the full costs of occupying high-hazard areas are simply greater than the probable advantages. Under those circumstances, flood insurance premiums which place the full costs on those benefiting from the location can operate to keep unwarranted occupancy to a minimum (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, 1966).

In accordance with earlier proposals, that report argued that flood insurance should be offered in partnership with the private sector. Congressional testimony by HUD, and ultimately the original NFIP legislation, was based on the findings of that report and its appendixes.

__________________

1The 1966 report described this “occupancy charge” as an ideal policy instrument, but for practical reasons recommended a program of flood insurance. It further stated that “The full costs of flood plain occupance would be shifted to the prospective occupants themselves through the imposition of mandatory, risk-related, annual occupancy charges. The charge would be equivalent to the occupant’s estimated annual damages plus any costs his occupancy causes others. These payments would be made to an indemnification fund which would be used to compensate those suffering flood damages.”

THE NATIONAL FLOOD INSURANCE PROGRAM: A BRIEF HISTORY

The National Flood Insurance Act of 1968 (Public Law 90-448) created the National Flood Insurance Program, which was to be administered by HUD. Although modified many times, the act remains the legislative foundation of the NFIP. In creating the NFIP, Congress identified two primary objectives: to encourage state and local governments to use land-use adjustments to constrict development of land exposed to flood hazards and guide future development away from such locations, and provide flood insurance through a cooperative public–private program with equitable sharing of costs between the public and private sectors (42 US Code, Section 401 Congressional Findings and Statement of Purpose). With respect to insurance, the law provided that local communities limit new development in some areas of the floodplain, which later were known as Special Flood Hazard Areas (SFHAs; see Appendix E). Once a community agreed to such limits, its citizens would be able to purchase flood insurance policies offered by private insurers in a partnership with the federal government. The mechanism for the partnership was the flood insurance risk pool. The Senate Committee on Banking and Currency described the pool as follows (U.S. Senate Committee on Banking and Currency, 1967):

Insurance industry pool

The insurance pool authorized by this bill will be an association of private insurance carriers formed to make flood insurance available. It will be open to all qualified companies licensed to write property insurance under the laws of the separate States who meet minimum requirements prescribed under the bill. Relations between the Government and the insurance pool will be governed by an agreement which will set forth in detail the conditions of operation.

Participation in the pool by private companies can take the form of risk capital participation. Some companies can elect to operate as fiscal agents for risk-taking members of the pool. The significance of this arrangement is that small companies with limited capital resources will not be prevented from participating.

Operation of the pool

Participating member companies of the pool, either as risk bearers or as fiscal agents, will sell and service policies in much the same way as they now sell insurance against fire and other perils. Their relationship with the pool will be governed by an agreement, the conditions of which will be subject to approval by the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development. As fiscal agents they will be paid fees for selling and servicing of policies. As risk bearers, they will share in the aggregate profits or losses of the pool’s operation for a particular accounting period. Risk-bearing member

companies will be jointly liable for the payment of claims by insolvent members. The Government-pool relationship will be governed by an agreement setting forth financial and other arrangements.

The agreement governing the pool partnership would make private risk-bearing possible, but would at the same time be designed to keep premiums reasonable.2 In practice, the desire to keep rates “reasonable” resulted in two NFIP design features. First, the legislation gave the NFIP authority to borrow from the US federal Treasury, which allowed it to make loans to the pool so it would be able to honor claims for noncatastrophic events. Such loans would be repaid in years when premium revenues exceed claims. That was especially important in the early years of the program before a reserve had been built up. More importantly, as a financial matter, the legislation designated the federal Treasury as the reinsurer and allowed it to bear the cost of catastrophic-loss events; these are low-probability—high-damage storms that result in widespread damage and total claims that greatly exceed the reserves (in the case of the NFIP the borrowing authority) available to pay claims. Because the Treasury was to be the reinsurer once claims in a given year exceed a specified level, an NFIP risk-based premium would not need to include expected claims from catastrophic-loss events, thus keeping NFIP risk-based premiums at reasonable levels.3

Second, premiums would be based on less than NFIP risk-based rates for some properties. At the time of the legislation, structures had been constructed in the nation’s floodplains with little understanding of or regard for flood risk, in part because flood risks had not been adequately delineated by public agencies and in part because many local governments had not enacted zoning or other regulations to take flooding into consideration when providing permits for new construction. NFIP risk-based premiums for those existing structures would have been extremely high. The legislation deemed such premiums to be unreasonable and created two rating systems for setting premiums. Owners of buildings constructed in the floodplain after flood insurance rate maps (FIRMs) were issued would pay NFIP risk-based rates to the private member of the pool that offered policies. A second rate structure would be used for pre-existing development so that the owners of existing structures would pay less than NFIP risk-based rates. The expectation was that these properties eventually would be lost to floods and storms, and that the need for premiums lower than NFIP risk-based rates would phase out by that attrition.

__________________

2See Chapter 1, Box 1-2, for elaboration of the term “reasonable” in the NFIP policy premium context.

3The financial rules governing the pool could result is some premium receipts being paid for reinsurance, but as a practical matter reinsurance was being offered at no charge to the pool.

The same 1967 report from the Senate Committee on Banking and Currency explained the pool’s financial arrangement:

Financial arrangements with Government

Testimony of witnesses at the hearings developed the fact that, for a number of months, discussions had been going on between the Department of Housing and Urban Development and industry as to the financial arrangements which could be made for operating the proposed joint flood insurance program. An understanding has been reached on the broad features of expenses, losses, and profits.

Among the broad features of the financial arrangements which have been discussed, one key feature is that the Government and the industry will both share in expenses and losses of the insurance operation. The basis for this sharing will be the same as the sharing in the risk.

The sharing in risk will be measured by the relationship between chargeable premiums—that is the premiums which policyholders pay—and the estimated risk premiums—that is, the premium needed to cover the actuarial risk plus operating costs and allowance. The Government will assume that proportion of the risk represented by the difference between these policyholder-paid premiums collected and the estimated (actuarial) premium amounts for all policies written and in force under the program.

In practice, at the end of each year the federal Treasury would make a subsidy payment to the pool equal to the difference between the revenue that would have been earned from sale of NFIP risk-based premiums and the premium charged for existing properties. Once properties eligible for pre-FIRM rates were no longer part of the portfolio, the only payments from the Treasury to the pool would be for loans, or in the event of a catastrophic loss. Taken together, those two provisions provided the underlying financial structure for ensuring that premium revenues would equal claims paid plus expenses over time. The 1967 report of the Senate Committee on Banking and Currency stated:

As the program develops, it can be expected that the industry’s risk and share of losses will become greater. This is because existing properties will be substantially improved or replaced by new properties, and therefore, more and more of the chargeable premiums will become full cost premiums. At some time in the future, therefore it is possible for the chargeable premiums to equal the estimated premiums. At that time, the Government will have no liability for expenses or losses, except with respect to reinsurance that may be needed against catastrophic losses. This feature of the proposed arrangement seems to the committee to be desirable from the standpoint of the Federal Government, the private insurance industry, and the public as a whole.

Within a decade, however, the original concept of partnering with the private sector was replaced by the NFIP taking full responsibility for rate setting and risk bearing. In 1979, President Carter signed an order creating the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). The Federal Insurance Administration (FIA) and the NFIP were moved from HUD and placed under the aegis of FEMA. FEMA almost immediately took action to provide technical floodplain management assistance in communities that had no state or local offices equipped for such work.

FEMA moved to implement the NFIP without a private risk-sharing partner. Instead, it engaged private “write your own” (WYO) companies to act as NFIP policy servicing agents. The WYO program allowed insurance companies to sell and manage flood insurance policies in their own names, which encouraged sales. The companies also would process claims but would not bear any risk or set rates. Even though the risk pool and private partnerships were no longer in effect, communities still had to take the floodplain management actions required to enroll in the program before property owners could purchase insurance.

Eligibility in the program required a community’s flood exposure and probabilities to be assessed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in order to create FIRMs and flood hazard boundaries, with FEMA calculating the insurance rates. Significantly, the imperative to keep premiums low for existing properties carried over to the NFIP in its new role. With the pool no longer in place, however, the Treasury had no obligation to transfer funds each year to the NFIP (instead of to the pool) to make up for revenues foregone by offering some properties less than NFIP risk-based rates. Revenues from the former fund transfer were replaced by a process of implicitly adding a charge to premiums on all policies (see Chapter 3 for discussion of the historical average loss year). Equally important, the fundamental premise that premiums should be kept reasonable to encourage purchase retained its level of importance in the federally administered NFIP.

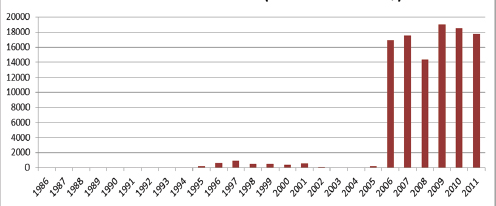

Another provision that carried forward was that a loan from the Treasury was taken to pay claims in high-loss years and was paid back in low-loss years. Hurricane Katrina and other storms in 2005 resulted in unprecedented NFIP payments to settle claims. In fact, the NFIP paid out more claims from 2005 than it had paid over the life of the program to that point (Kousky and Kunreuther, 2014), and this required substantial borrowing. Hurricane Ike in 2008 and Hurricane Sandy in 2012 further deepened the debt. Figure 2-1 shows debt peaking in 2009 and falling to less than $18 billion by the end of 2011. As of December 31, 2013, however, debt had risen again to $24 billion. The increase in debt stimulated congressional debate and led to the BW 2012 reform legislation that in part focused on the revenue adequacy of NFIP premiums.

FIGURE 2-1 NFIP cumulative debt (millions nominal $).

SOURCE: King, 2013.

LEGISLATIVE CHANGES: BIGGERT-WATERS 2012 AND HOMEOWNER FLOOD INSURANCE AFFORDABILITY ACT OF 2014

Through a number of specific provisions, BW 2012 emphasized the need to have premium revenues and associated fees eventually cover payouts for claims and NFIP program expenses. To that end, FEMA was directed to change the premiums it was charging to reflect more fully the risks for all classes of policyholders. FEMA was to replace the lower rates for existing properties (which FEMA had called pre-FIRM subsidized rates) that had been offered since the beginning of the program with NFIP risk-based premiums.

The practice of grandfathering had been introduced by FEMA to allow property owners who met specific conditions to keep a lower rate in the event that an updated FIRM showed that they were at a greater flood risk than originally believed. Under BW 2012, following a change to a local FIRM, grandfathered rates were to be phased into NFIP risk-based rates over five years. Other provisions of BW 2012 directed FEMA to review and report on reserves and purchase of private reinsurance presumably with the costs to be recovered by adding to NFIP risk-based premiums.

BW 2012 acknowledged concern for whether NFIP risk-based premiums for all would make premiums unaffordable for some in Section 100236, which called on FEMA to conduct an affordability study. The FEMA study was to be concurrent with implementation of the rate-increasing reforms; thus, the reforms moved forward with no program of assistance in place for policyholders who were required to purchase a policy and might face an unaffordable premium increase.

As implementation of BW 2012 began, the premium increases became a topic of testimony and letters that argued that the proposed changes would result in premiums that were unaffordable to many, and possibly cause economic disruption in communities across the nation. In response, Congress passed HFIAA 2014, which repealed or modified many (but not all) of the rate reform changes that had been enacted in BW 2012. Notably, HFIAA 2014 reinstated the policy of grandfathering premiums. It did not change the sections of BW 2012 that directed FEMA to review aspects of its program that might affect NFIP risk-based rates. A concern expressed in HFIAA 2014 was that the higher premiums would no longer be reasonable, and they would be so high as to discourage purchase of NFIP policies. Section 9 of HFIAA 2014 expressed a concern about “The impact of increases in risk premium rates on participation in the National Flood Insurance Program.”

TAKEUP RATES: A CONTINUING CONCERN

The original intent of the NFIP was to set premiums and have rules for insurance purchase that would serve the nation’s broad flood risk management goals. The NFIP was expected to minimize taxpayers’ costs of disaster recovery by substituting insurance payouts for aid. One NFIP objective was to encourage community floodplain management. The NFIP also sought to advance public understanding of flood risks through risk mapping and risk communication programs. NFIP risk-based insurance premiums were going to help households understand the flood risk at particular locations (or at least the cost of living in such locations), and ensure that the floodplain occupant bore the cost of locating in places that had appreciable flood risks. In order for those goals to be realized, however, the insurance needed to be purchased.

Therefore, in designing the NFIP to help attain these broad flood risk management objectives, Congress always has emphasized the need for high takeup rates, and one means to that end is to keep NFIP premiums reasonably priced. As the NFIP was being created, Congress presumed that once communities learned about the low-cost premiums for existing homes, they would adopt the regulations needed to join the program, and allow residents to purchase coverage under the NFIP. It also was presumed that homeowners and small businesses in eligible communities would enroll eagerly in the NFIP.

Hurricanes in 1969 (Camille) and 1972 (Agnes), however, revealed that only a few communities at risk of flooding had enrolled in the program. When Hurricane Agnes caused extensive damage to Pennsylvania and other East Coast states in June 1972, few parties had purchased insurance, and the NFIP paid $3 million in claims of a total of $3 billion of estimated dam-

ages (Anderson, 1974). To encourage additional NFIP policy purchases, in 1973 Congress passed the Flood Disaster Protection Act (FDPA), which required property owners who were receiving mortgages from federally backed or regulated lenders and whose properties were located in a 100-year floodplain (the SFHA) to purchase flood insurance. Further, to ensure eligibility for all forms of disaster assistance, the new law required communities to participate in the NFIP. The same act reduced the rates for existing properties for the following 7 years in the hope of encouraging participation in the program.

Nonetheless, in 1993, after large floods on the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers, it was found that less than 20% of the flooded structures had been insured (Galloway, 1995). That low takeup rate was part of the impetus for passage of the National Flood Insurance Reform Act of 1994. Provisions of that bill (and which continue today) that were expected to increase enforcement of the mandatory purchase requirement included the following: coverage now is required over the life of a loan, lenders must escrow flood insurance payments when they require escrows, lenders need to obtain flood insurance policies if borrowers do not, and failure to comply with the mandatory purchase requirement can result in the fining of lenders. In addition, to prevent last-minute purchase only when flooding is imminent, the time between purchase of flood insurance and its going into effect was increased to 30 days. The law also prohibited further flood disaster assistance for any property for which flood insurance was not maintained after having been mandated as a condition for receiving disaster assistance. The latter measure was added in recognition of the fact that loan or grant programs, to the extent that they parallel the insurance mechanism, can undermine the ability of the insurance program to operate efficiently and equitably (Hayes, 2003; Knowles and Kunreuther, 2014).

Throughout its history, the NFIP has been asked to set premiums that are simultaneously “risk-based” and “reasonable.” Different administrations and successive sessions of the U.S. Congress have placed varied emphases and priorities on those goals for premium setting. The tensions between these goals are noted in a comment from FEMA that reflect on the early years of the NFIP (Hayes and Neal, 2011):

Providing certain statutory amounts of insurance at less than full-risk rates was justified as public policy for the following reasons:

(1) Lower premiums for existing construction made it easier to convince communities to join the NFIP. It was very important in the early years of the NFIP to increase community participation so that sound floodplain

management was implemented and the nation’s exposure to flood would thereby be slowly but significantly reduced.

(2) It was anticipated that very high premiums would cause great resistance to insurance purchase. However, with reasonable premiums, property owners purchasing insurance at less than full-risk rates would still be funding at least part of their recovery from flood damage. This was considered preferable to the previous arrangement of disaster relief that came solely from taxpayer funding.

(3) In the public policy discussions leading to the authorization of the NFIP, it was determined to be undesirable to potentially force, through high flood insurance premiums, the abandonment of otherwise economically viable buildings.

- From the inception of the NFIP, and continuing until BW 2012, Congress sought to achieve multiple objectives for the program. The objectives have been to (1) ensure reasonable insurance premiums for all, (2) have NFIP risk-based premiums that would make people aware of and bear the cost of their floodplain location choices, (3) secure widespread community participation in the program and substantial numbers of insurance policy purchases by property owners, and (4) earn premium and fee income that, over time, covers claims paid and program expenses. These objectives, however, are not always compatible, and at times may conflict with one another.

- The premium-setting practices and procedures that were in place before Biggert-Waters 2012 reflected the multiple objectives of the NFIP, and in some cases reflected premium-setting practices that were put in place when the NFIP was created. BW 2012 increased the emphasis on setting NFIP rates that reflected flood risk, and on charging premiums that would cover claims paid and other related expenses.

This page intentionally left blank.