5

Locations of Potential National Flood Insurance Program Affordability Challenges

Before passage of Biggert-Waters 2012 (BW 2012), the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) used different premium setting practices for different groups of policies: NFIP risk-based (including preferred risk), grandfathered, pre-flood insurance rate map (pre-FIRM) subsidized, and Community Rating Service discounted (CRS discounted). BW 2012 would replace pre-FIRM subsidized and grandfathered premiums with NFIP risk-based rates. The removal of subsidies, and the move toward risk-based rates, can raise premiums for pre-FIRM subsidized and grandfathered policies. BW 2012 also directed FEMA to report on the feasibility of purchasing private reinsurance, to pay down the debt to the Treasury, and to take actions to build up the NFIP reserve fund. Those actions may require FEMA to increase NFIP risk-based premiums, and this would affect all classes of policies.1

As premiums increase, the changes in premiums may make insurance unaffordable to some households. There may be locations where increases have adverse effects on a community if premiums increase for a large number of its residents. Before detailed discussion of how affordability might be defined (Chapter 6), and how aid programs might be developed if there are affordability concerns (Chapter 7), this chapter discusses the geographic distribution of policies for each policy group. The result is to provide a perspective on the location and extent of potential affordability challenges if all

__________________

1The Homeowner Flood Insurance Affordability Act of 2014 reinstated grandfathering. The present committee’s task statement, however, which was derived from BW 2012, presumes that all premiums eventually would be NFIP risk-based, which is the presumption of this chapter.

provisions of the BW 2012 legislation were implemented. This information has important implications for decisions regarding national level affordability policy design. For example, if a large portion of the potential premium increases was concentrated in a few counties, affordability policy options might be different from what they might be if the potential increases were spread across the entire nation.

This chapter presents several maps that describe the spatial distribution of policy groups. The data used to generate these maps was as follows:

- FEMA Flood Insurance Policy Database. This database contains the location of all the flood insurance policies as of October 2013. It provides such information as the address of the policy, the current premium, and the zone in which the policy was rated. This restricted dataset cannot be released to the public because of privacy issues. Results are reported in such a way that privacy is protected.

- U.S. Census Geographical Area. This dataset provides the geographic boundaries of approximately 220,000 census-block groups from the 2010 census that form the area of the United States and all territories.

- FEMA National Flood Hazard Layer. This dataset has the flood boundaries of all the digital maps that exist in FEMA’s inventory as of 2010.

Maps, tables, and data compilations in this chapter were prepared by the AECOM firm, which used FEMA 2013 data that it acquired under a separate contractual agreement (AECOM, 2014). The data above were combined to create the maps in this chapter. Data analysis generally was performed within a spreadsheet, and the results were mapped with a geographic information system (GIS). For example, to show locations of policies, a spreadsheet is used to summarize the Flood Insurance Policy Database, and the summary is then imported into a GIS to be mapped. The spreadsheet used for the present report is Excel 2010 and the GIS used was ArcGIS10.2.2.

The chapter first describes the current NFIP policy portfolio. The geographic distribution of policies included in each policy group is then reported. That reporting is at the state, county, or US Census block group of aggregation as needed to understand the location of a policy group.

NATIONAL FLOOD INSURANCE PROGRAM POLICIES IN FORCE: AN OVERVIEW

Overview

The NFIP had 5,544,629 standard policies in force2 as of October 2013. A FEMA standard flood insurance policy3 can be issued for several types of properties:

- Single family housing units, which account for 3,793,421 of the policies in force

- Properties that contain two to four housing units, which account for 264,650 of the policies in force

- Properties that contain more than five housing units, such as apartment buildings and assisted living facilities, which account for 1,192,402 of the policies in force

- Nonresidential properties (buildings for businesses) and residential facilities, such as hotels with short-term guests; Residential Condominium Building Association Policy properties (this applies to condominium complexes whose individual units are separately owned), which account for 294,156 of the policies in force.

Those distinctions are important in understanding the policy database and the presentation of the data in this chapter. Note that a policy may be for a property that has more than one housing unit; an example would be an apartment building.

For residential properties, a further distinction is made concerning whether the property is a primary or non-primary residence. “FEMA defines a primary residence as a building that will be lived in by an insured or an insured’s spouse for more than 50% of the 365 days following the policy effective date.”4 Also, a separate category of properties—Severe Repetitive Loss (SRL) properties—are ones that have had four or more separate claim

__________________

2The information and maps describing NFIP policies in this chapter are derived from data provided to the committee by FEMA. This is the most recent detailed data (October 2013; see FEMA, 2013b) available on flood insurance policies. FEMA policies in force vary from year to year so policy counts made at other times may differ from the counts reported here. The basic unit of consideration for representing the location of these policies is the housing unit, defined by the US Bureau of the Census as follows: “A housing unit is a house, an apartment, a mobile home, a group of rooms, or a single room that is occupied (or if vacant, is intended for occupancy) as separate living quarters. Separate living quarters are those in which the occupants live and eat separately from any other persons in the building and which have direct access from the outside of the building or through a common hall.”

3NFIP Flood Insurance Manual, General Rules Section, p. GR-2, 1 June 2014.

4Source: NFIP Flood Insurance Manual, Definitions Section, p. DEF-7, 1 June 2014.

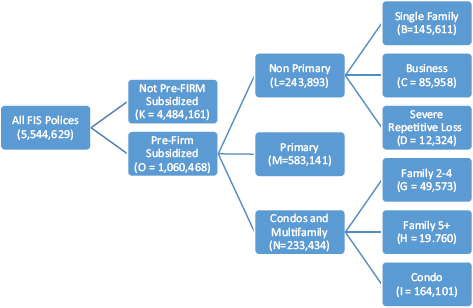

FIGURE 5-1 Classification of flood insurance policies.

SOURCE: AECOM, 2014.

payments that each exceed $5,000 or two or more separate claim payments, the total of which exceeds the current value of the property.5

Figure 5-1 depicts a classification of these types of policies. The total number of policies in force in the NFIP portfolio is divided into “not pre-FIRM subsidized” and “pre-FIRM Subsidized.” Included in the not pre-FIRM subsidized group are NFIP risk-based policies, grandfathered policies (discussed separately below), and CRS discounted polices. About 20% of the policies are subject to pre-FIRM subsidized premiums.

Figure 5-1 subdivides pre-FIRM subsidized policies into categories. Non-primary properties (designated by L) consist of single family homes (B), businesses and nonresidential buildings (C), and severe repetitive loss properties (D); L = B + C + D. L properties cover policies that under BW 2012 would see increases in rates of 25% per year until the NFIP risk-based premium was paid; the Homeowner Flood Insurance Affordability Act of 2014 (HFIAA 2014) did not change that BW 2012 requirement.

____________________

5Source: NFIP Flood Insurance Manual, Severe Repetitive Loss Section, p. SRL-1, 1 June 2014.

The second category of policies is for primary residences (M), which total 583,141 policies. This is the category of policies that under BW 2012 would have seen increases in rates of the NFIP risk-based premium when the property was sold. However, HFIAA 2014 replaced that provision by requiring that rates increase by 5-18% per year until the NFIP risk-based premium was being paid. HFIAA 2014 also allowed the NFIP risk-based premium to phase in over time even if the property was sold.

The third category of policies is for multifamily residences (N), which total 233,434. It includes residences with two to four housing units (G), five or more housing units (H), and Residential Condominium Building Association Policy (RCBAP) units (I); N = G + H + I. The condominium category includes units that are owner-occupied and rental properties; most of the condominium units that have pre-FIRM subsidized policies (150,226) are not primary residences. The total number of properties with pre-FIRM subsidized policies that would be affected by BW 2012 is O = L + M + N. This total of 1,060,468 is displayed later in discussions of pre-FIRM subsidized policies.6

All National Flood Insurance Program Policies

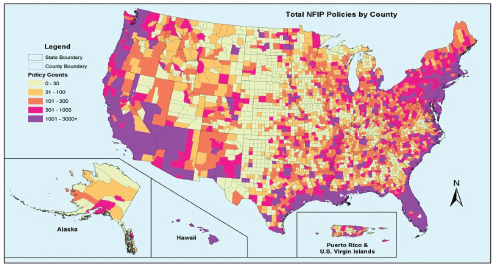

Figure 5-2 shows the distribution of all 5.5 million policies throughout the nation by county. As the figure shows, NFIP polices are distributed widely, but there are areas of high concentration.

Table 5-1 lists the numbers of NFIP policyholders throughout the nation by state or territory. The table shows the concentrations of policy holders in select areas of the United States. For example, Florida contains 40% of the policies, and Texas and Louisiana together contain 20% percent of the policies.

BW 2012 would affect premiums levels for all these policy types in all these places and in different and undetermined ways. Thus, its effects may be concentrated in some states but be present throughout the nation.

The roughly 5.5 million policies in force today are both in and outside the FEMA-mapped Special Flood Hazard Areas (SFHA; 1% floodplain), but not all the properties in SFHAs have purchased insurance. Estimating takeup rates is difficult because of the lack of data on households and policies in floodplains around the country. It appears that takeup rates are particularly low in areas where purchase is voluntary, but it also seems that many people who are required to purchase the coverage do not. The RAND

__________________

6Although those distinctions are important for understanding the changes that HFIAA 2014 made in BW 2012, the focus of this report is the NFIP premiums charged to all policyholder under the rating and premium-setting process before BW 2012 and under the rating and premium-setting process after BW 2012.

FIGURE 5-2 NFIP policies in the United States by county.

SOURCE: AECOM, 2014.

Corporation estimates that about half a random sample of single-family homes in 100-year floodplains across the country have flood insurance, but this masks high regional variation; the Midwest has the lowest takeup rates—20-30%—and the South and West having takeup rates closer to 60% (Dixon et al., 2006). An examination of coastal properties estimated takeup rates at 50% (Kriesel and Landry, 2004). And a calculation of takeup rates in census tracts (not only in floodplains) along the New Jersey and New York coasts immediately before Hurricane Sandy suggests that market penetration was in the range of 50%, with a few tracts along the coast having rates up to 75% (Kousky and Michel-Kerjan, 2012).

In July 2014, FEMA reported to Congress that 4.9 million housing units are in the riverine or SFHA floodplain (or 1% floodplain) and 3.8 million in the coastal SFHA, for a total of 8.7 million housing units in floodplains (Doug Bellomo, 2014, Federal Emergency Management Agency, personal communication). About 5.5 million NFIP policies are in force in and outside the SFHA; given that over 11 million housing units are in the SFHA alone, it appears that many of the housing units in the nation’s floodplains do not have flood insurance. These analyses based on available data suggest that meeting the long-standing goal of high takeup rates for flood insurance would require a significant increase in insurance policy purchases.

TABLE 5-1 NFIP Polices by State or Territory

| STATE | NUMBER OF POLICIES |

| Alabama | 58,256 |

| Alaska | 3,014 |

| American Samoa | 2 |

| Arizona | 34,885 |

| Arkansas | 21,065 |

| California | 273,339 |

| Colorado | 22,913 |

| Connecticut | 43,400 |

| Delaware | 25,585 |

| District of Columbia | 2,361 |

| Florida | 2,029,025 |

| Georgia | 96,872 |

| Guam | 253 |

| Hawaii | 59,315 |

| Idaho | 6,937 |

| Illinois | 49,232 |

| Indiana | 29,573 |

| Iowa | 16,410 |

| Kansas | 12,867 |

| Kentucky | 25,051 |

| Louisiana | 483,218 |

| Maine | 9,319 |

| Maryland | 73,995 |

| Massachusetts | 59,773 |

| Michigan | 25,185 |

| Minnesota | 12,093 |

| Mississippi | 74,095 |

| Missouri | 26,206 |

| Montana | 5,876 |

| Nebraska | 12,709 |

| Nevada | 14,611 |

| New Hampshire | 9,489 |

| STATE | NUMBER OF POLICIES |

| New Jersey | 246,498 |

| New Mexico | 16,200 |

| New York | 196,717 |

| North Carolina | 139,121 |

| North Dakota | 13,755 |

| Northern Mariana Islands | 10 |

| Ohio | 41,676 |

| Oklahoma | 17,742 |

| Oregon | 34,085 |

| Pennsylvania | 73,950 |

| Puerto Rico | 43,959 |

| Rhode Island | 16,101 |

| South Carolina | 206,611 |

| South Dakota | 5,456 |

| Tennessee | 32,780 |

| Texas | 629,862 |

| US Virgin Islands | 2,090 |

| Utah | 4,511 |

| Vermont | 4,579 |

| Virginia | 115,481 |

| Washington | 44,804 |

| West Virginia | 20,915 |

| Wisconsin | 16,104 |

| Wyoming | 2,506 |

| (Records Missing Geocoding) | 2,192 |

| Grand Total | 5,544,629 |

SOURCE: AECOM, 2014.

Grandfathered Policies

Grandfathered policies7 are created when a new version of the FIRM is released and current policyowners want to be rated on the basis of the map that was in effect when the policy was initially purchased. For example, consider a homeowner whose house has a first-floor elevation of 52 ft. In 2008, the owner purchased flood insurance, and the maps show the 100-year flood at an elevation of 53 ft on the basis of a map dated 1983. The homeowner is charged an insurance rate for a first floor that is 1 ft below the 100-year base flood elevation. In 2012, a new FIRM shows a 100-year flood elevation to be at 55 ft, or 3 ft above the first-floor elevation of the house. The policyowner can keep the lower rates of first floor elevation 1 ft below (vs 3 ft below) the 100-year flood elevation if specific conditions exist. Thus, rates may increase, and the design of an affordability framework would be well served if the number and location of grandfathered policies were known.

The FEMA policy database does not contain information on whether a current policy is grandfathered. It does contain the zone that was used at the time the policy was purchased; if the elevation of the structure was obtained, that information is also in FEMA’s database. In addition, FEMA maintains a National Flood Hazard Layer (NFHL) for areas where the paper map inventory has been converted to a digital format. NFHL are available for communities that include approximately 88% of the US population and approximately 60% of the land area of the continental United States (see NRC, 2009 for further discussion of FEMA floodplain mapping modernization). The NFHL is the combination of all the community flood hazard information into one database layer in which digital flood maps exist. FEMA also has addresses of policies. The flood policies can be geocoded and intersected with the current map to determine the current flood zone of properties. The following indicators can then be used to determine whether a policy is grandfathered:

- Policy is rated as a Zone X (outside the 100-year floodplain) and now is shown in Zone A (inside the 100-year floodplain).

____________

7“Under NFIP administrative grandfathering, post-FIRM buildings in the Regular Program built in compliance with the floodplain management regulations in effect at the start of construction will continue to have favorable rate treatment even though higher Base Flood Elevations (BFEs) or more restrictive, greater risk zone designations result from Flood Insurance Rate Map revisions. Policyholders who have remained loyal customers of the NFIP by maintaining continuous coverage (since coverage was first obtained on the building) are also eligible for administrative grandfathering” (FEMA, 2014b).

- Policy is rated as a Zone X (outside the 100-year floodplain) and now is shown in Zone V (inside the 100-year floodplain and in an area of high wave action).

- Policy is rated as a Zone A (inside the 100-year floodplain) and now is shown in Zone V (inside the 100-year floodplain and in an area of high wave action).

In addition, grandfathering occurs when the flood map elevation increases. The current elevation of the 100-year flood map can be determined with available information. A calculation to locate and map grandfathered premiums was beyond the data and time resources available to the committee for the present report. FEMA has, however, made preliminary estimates of grandfathering and has concluded that, at a national level, approximately 10% of all policies (excluding pre-FIRM subsidized) are grandfathered (Andy Neal, Federal Emergency Management Agency, personal communication, 2014).

Policies Other Than Pre-FIRM Subsidized

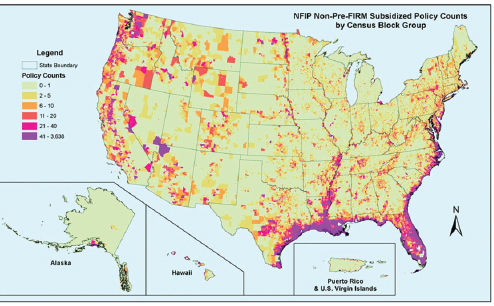

BW 2012 called on FEMA to report to Congress on the possibility of making changes that might raise NFIP risk-based premiums. Figure 5-3 maps the distribution of all policies other than pre-FIRM subsidized, according to US Census block group;8 these are policies that might be affected by changes in premiums even if they are not currently paying pre-FIRM subsidized premiums.

Although there are areas of concentration these policies in this group (purple in Figure 5-3), policies in this group are found in large numbers in census block groups around the nation (pink and red shading in Figure 5-3).

Pre-FIRM Subsidized

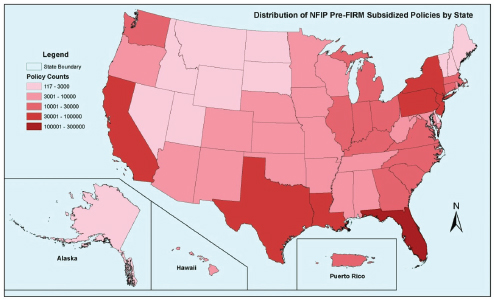

Holders of pre-FIRM subsidized policies may see significant increases in premiums. The spatial pattern of significant premium increases for NFIP pre-FIRM subsidized policies is shown by state in Figure 5-4. The states that have the largest populations—California, Texas, New York, and Florida—have large numbers of pre-FIRM subsidized policies and high numbers of

__________________

8A census block group has a population of 600-3,000 people, or an average of 533 housing units. As of 2013, the US population was approximately 316 million, and there were approximately 133 million housing units. To assemble data on the population, counties are assembled or divided into census tracts, of which there are about 74,000. Those are subdivided into census block groups (220,000) and then into census blocks (11 million). A US census block Group contains an average of 600 housing units (for more information see https://www.census.gov/geo/maps-data/data/tallies/tractblock.html).

FIGURE 5-3 NFIP non—pre-FIRM subsidized policy counts by US Census block group.

SOURCE: AECOM, 2014.

FIGURE 5-4 Distribution of NFIP pre-FIRM subsidized policies by state.

SOURCE: AECOM, 2014.

all policies. Louisiana, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania round out the top seven states of NFIP pre-FIRM subsidized policy numbers.

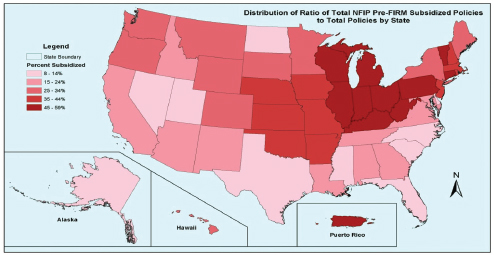

Another perspective on the location of pre-FIRM subsidized premiums is presented in Figure 5-5. The figure illustrates the spatial pattern of the ratio of pre-FIRM subsidized to total flood policies [(O/(K+O)] in each state. It shows that the Midwest and Great Lakes regions have higher percentages of pre-FIRM subsidized policies, and the South and West regions have lower percentages. That is not surprising inasmuch as the southern and western United States is where population growth is creating newer housing stock (compared to the Midwest and Great Lakes regions), presumably built after the local FIRM was issued. Depending on perspective, possible affordability concerns due to removing pre-FIRM subsidies could be concentrated in different areas of the nation. If both perspectives are used, however, the possible affordability problem appears to be national in scope.

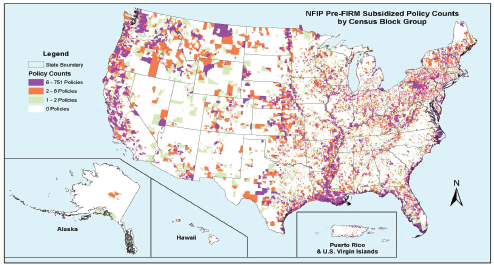

An even finer level of spatial detail can be used by allocating the policies to census block groups and then mapping the distribution of pre-FIRM subsidized policies at the census block group level. The impression from Figure 5-6 is that the pre-FIRM subsidized policies are spread widely, but an important calculation based on the data underlying the map shown is that 80% of NFIP polices are concentrated within 6% of the US census block groups. Focusing on the purple areas suggests that there are

FIGURE 5-5 Distribution of the ratio of total NFIP pre-FIRM subsidized policies to total policies.

SOURCE: AECOM, 2014.

FIGURE 5-6 NFIP pre-FIRM subsidized policy count rankings by US Census block groups.

SOURCE: AECOM, 2014.

small geographic areas (recall that an average census block group contains approximately 600 housing units) in which removing pre-FIRM subsidized premiums may affect a large percentage of households in a single community.

Determining whether there are concentrations of NFIP policies may be useful for designing a national affordability framework.

- About 60% of the approximately 5.5 million NFIP polices are in three states: Florida, Texas, and Louisiana. The rest are distributed widely throughout the nation. Any effects of BW 2012 therefore will be more concentrated in some places, but will appear throughout the nation.

- Available estimates of takeup rates suggest that they are low, especially outside Special Flood Hazard Areas. Meeting the long-standing goal of high takeup rates for flood insurance therefore would therefore require a large increase in purchases.

- The extent and location of premium increases that might result from elimination of grandfathering can be determined by further analysis of the policy data, but cannot be estimated now.

- Slightly more than 1 million—or 19% of the policyholders—are paying pre-FIRM subsidized rates and will potentially see rate increases if the provisions of BW 2012 remain in effect. Pre-FIRM subsidized polices are found throughout the nation, but there are areas of concentration.

6

Affordability Concepts and a Framework for Assistance Program Design Decisions

Section 9 of the Homeowner Flood Insurance Affordability Act of 2014 (HFIAA 2014) required FEMA to propose an affordability framework for the National Flood Insurance Program. That legislation requesting this framework asked FEMA to propose options for “Targeted assistance to flood insurance policy holders based on their financial ability to continue to participate in the National Flood Insurance Program.” A similar requirement is found in Section 100236 of the Biggert-Waters Act of 2012 (BW 2012), which called on FEMA to analyze “methods for establishing an affordability framework for the National Flood Insurance Program, including methods to aid individuals to afford risk-based premiums under the National Flood Insurance Program through targeted assistance rather than generally subsidized rates, including means-tested vouchers.”1

This chapter describes different concepts of affordability and associated ways of measuring the cost burden on a property owner or renter from purchasing flood insurance. Metrics for measuring affordability can be described, but the threshold for defining when an insurance premium creates a cost burden requires making a policy judgment. Given that some affordability criterion is chosen, the chapter presents a decision framework that could be used in the design of targeted assistance programs for flood insurance affordability. This framework presents a list of choices to be made by program designers: who will receive assistance, what type of assistance

__________________

1BW 2012 phased out grandfathered premiums, but HFIAA 2014 reinstated them. For purposes of this chapter and to be consistent with the committee’s task statement, this discussion assumes that all premiums have been raised to NFIP risk-based levels.

will be provided, how assistance will be provided, how much assistance will be provided, who will pay for assistance, and how an assistance program will be administered.

MEASURING THE COST BURDEN OF FLOOD INSURANCE PREMIUMS AND DEFINING AFFORDABILITY

Although a lower insurance premium clearly is more affordable than a higher premium, there is no objective threshold that separates affordable premiums from unaffordable premiums, and thus defines affordability, either for an individual property owner or renter, or for any group of property owners or renters. Instead, there are many subjective concepts of affordability that are influenced by social norms and can be informed by, for example, data on income and expenditure patterns or experience in operating social assistance programs. Those concepts reflect concerns about how premium increases might affect both willingness and ability to purchase insurance. The concern about the ability to purchase was especially relevant in the BW 2012 and HFIAA 2014 language in light of legal and regulatory provisions that make purchase of insurance mandatory if a property in a Special Flood Hazard Area has a federally backed mortgage.

This section discusses three of the many potential approaches to the concept of affordability: a capped-premiums approach, an income approach, and a housing-cost approach. Those approaches specify different ways of measuring the cost burden on a property owner or renter of having to buy flood insurance. According to each approach and its associated cost burden measure, flood insurance is assumed to become unaffordable when the cost burden becomes excessive. What constitutes “excessive” must be specified by policymakers, who must also choose the affordability concept(s) that will be used for the NFIP. As discussed later, a chosen affordability concept and cost burden measure can be used to establish eligibility criteria for a program that provides financial assistance to make flood insurance more affordable. The cost burden measure also can be used to monitor changes in affordability of flood insurance and differences in affordability of insurance between areas or types of households.2

__________________

2Although as discussed in this report, flood insurance is considered to be unaffordable to a household if and only if the household is cost burdened by having to pay for flood insurance, being cost burdened does not necessarily imply that a household would be eligible for financial assistance. Further, a household could be eligible for assistance without being cost burdened, as surely has been the case for some households under NFIP pre-FIRM subsidy and grandfathering provisions.

Capped Premiums Approach

In Section 16 of HFIAA 2014, Congress proposed a capped premiums approach. Under this concept of affordability, a flood insurance premium is defined as not affordable if it is greater than a specified percentage of the coverage of the policy. HFIAA 2014 suggested that this threshold value be 1%. The capped premiums approach does not consider household income, assets, or expenditures on housing, food, medical care or other goods and services in determining whether a flood insurance premium imposes a cost burden.

Income Approach

Many federal and state assistance programs, as well as provisions of the federal income tax code, provide assistance with housing costs and other expenses that is based on household income. For example, eligibility for public housing is limited to low-income and moderate-income households whose incomes do not exceed 80% of the median income in their county or metropolitan area. Housing assistance through rent subsidies (housing vouchers) administered by local housing authorities generally is limited to low-income households (those whose income does not exceed 50% of the median income of the county or metropolitan area in which it is located), and by law, 75% of vouchers must be provided to households whose income does not exceed 30% of the area median income. To be eligible for benefits under the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly the Food Stamp Program), a household—with some important exceptions—is eligible if its monthly gross income is at or below 130% and its monthly net income is at or below 100% of the applicable federal poverty guideline.

On the basis of the concepts underlying the designs of these and other programs, an income approach to affordability assumes that flood insurance imposes a cost burden and is thus unaffordable for any household whose income is below a specified standard. That standard could be based on median income for the area or federal poverty guidelines, for example, and could be set to include not only low-income but also a substantial fraction of moderate-income households among those judged to be cost burdened by the new flood insurance premiums. In any case, the standard chosen would have to be specified by policymakers.3

__________________

3Although this discussion refers to a “standard,” the standard could be a set of thresholds that vary by geographic area, household size and composition, and other characteristics.

Housing Cost Approach

This approach considers not only a household’s income but also housing costs, and assesses the ratio of housing costs to income when the NFIP premium is added to other housing costs. If the ratio exceeds a specified value, the flood insurance premium is regarded as cost burdensome and deemed unaffordable.

As its name implies, this concept of affordability has been used in research and assistance programs pertaining to housing (Hulchanski, 1995; Tighe and Mueller, 2013). In applying the concept to homeowners, housing costs typically include payments for mortgage principal and interest, property insurance (including flood insurance), property taxes, homeowner association or condominium fees, utilities (fuel for heating and air conditioning, water and sewer, and trash collection), and maintenance. In the case of renters, many of those costs are not paid separately but are combined in landlords’ calculations of monthly rent.

To use the housing cost approach for measuring the cost burden of NFIP premiums, policymakers would have to select the threshold—usually expressed as a percentage—at which the ratio of housing costs to income is judged to become burdensome and thus unaffordable. The US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) identifies households that experience housing costs of 30% of income or more as cost burdened and those who pay 50% or more as severely cost burdened.4 That affordability standard has been described as follows (Glaeser and Gyuorko, 2008):

A consensus seems to have arisen that housing becomes “unaffordable” when costs rise above 30 percent of household income. This is not only the standard used by the Millennial Housing Commission in its recent reports, but also is the basis for a number of U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) policies.

If policymakers were to choose the 30% threshold for the NFIP, for example, a household would be flood insurance cost burdened if its housing costs, including the NFIP premium, exceeded 30% of its income. Under that policy choice and criterion, the size of the burden would be the dollar amount beyond 30% of household income that would be required to pay for housing because of the amount of the flood insurance premium. For a household already housing cost burdened—because its housing costs without flood insurance exceed 30% of its income—the entire NFIP premium would be viewed as a flood insurance cost burden. For a household

__________________

4According to national Consumer Expenditure Survey data for 2013, the share of income spent on housing is 27.9% for the median homeowner without a mortgage, 34.1% for the median homeowner with a mortgage, and 38.5% for the median renter (http://bls.gov/cex/2013/combined/tenure.pdf).

that spends less than 30% of its income on housing, the flood insurance premium would be viewed as affordable as long as overall housing costs remain no higher than 30% of income.

A chosen affordability concept and cost burden measure can be used to monitor changes in the affordability of flood insurance and differences in the affordability of insurance between different areas or types of households. In addition, the concept and measure can be used to establish eligibility criteria for a program that provides financial assistance to make flood insurance more affordable. Choosing an affordability concept and cost burden measure, however, is only one decision that must be made in designing such a program. Additional decisions required of policymakers are discussed next.

A DECISION FRAMEWORK FOR DESIGNING TARGETED ASSISTANCE TO MAKE FLOOD INSURANCE MORE AFFORDABLE

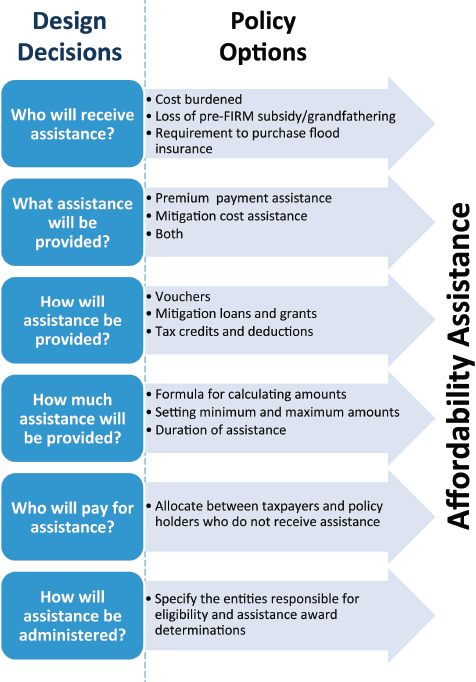

This section discusses decisions that policymakers must make when designing a flood insurance affordability assistance program. These design decisions are as follows:

- Who will receive assistance?

- What type of assistance will be provided?

- How will assistance be provided?

- How much assistance will be provided?

- Who will pay for assistance?

- How will an assistance program be administered? (See Figure 6-1.)

As described below, many of those decisions entail tradeoffs that involve incentives to purchase flood insurance, incentives to undertake mitigation activities, direct costs of assistance to make flood insurance more affordable, and administrative costs of providing such assistance. The present report discusses the nature of these tradeoffs in general terms. Possible analytic methods for assessing the tradeoffs will be described in this committee’s second report (which will be issued later in 2015).5

__________________

5Assistance program costs can be paid from general government revenues and can be recovered by charging cross-subsidies as added surcharges on all NFIP policies (such as temporary surcharges put into place by HFIAA 2014) or by raising levels of all premiums as is done to support Community Rating System and grandfathered premiums. There will be limits on general revenues made available, and substantial cross-subsidies that violate actuarial principles may cause concern. For those reasons, the consequences for the size of the required assistance budget will be a constant consideration in how the questions will be answered.

FIGURE 6-1 Considerations and policy options for designing an assistance program for a flood insurance affordability framework.

Decision 1: Who Will Receive Assistance?

In specifying who is eligible to receive assistance, policymakers could initially select an affordability concept and associated measure of cost burden. They could then consider whether to impose additional eligibility criteria. For example, should eligibility be limited to policyholders who previously received assistance through pre-FIRM subsidies or grandfathering? Should assistance be limited to low-income and moderate-income policyholders? Should assistance be considered for households that have experienced dramatic increases in flood insurance policy premiums? Those specific questions and broader issues in the specification of eligibility criteria are discussed next.6

Eligibility Based on Being Cost Burdened by Flood Insurance

Three affordability concepts and associated measures of cost burden were discussed in the first section of this chapter. Policymakers could select one of those concepts or measures or some other alternative. Once a concept and a measure have been selected, it will be necessary to define the components of the cost burden measure and specify any applicable thresholds. With the capped premiums approach, the percentage (premium relative to coverage) that identifies burdensome premiums would have to be selected. For the income approach, income has to be defined, and policymakers have to specify the income threshold (or set of thresholds) below which households are considered cost burdened by flood insurance.7 The housing cost approach requires a definition of housing costs, a definition of income, and a threshold that identifies the ratio of housing costs to income at which housing costs are considered burdensome.

After a cost burden measure has been selected, its components have been defined, and the applicable thresholds have been specified, whatever data needed to measure a particular household’s flood insurance cost burden would have to be obtained and used by the agency that is administering the assistance program to determine whether the household is cost burdened. The housing cost approach could impose substantial reporting burden on households that have to provide data on income and expenses and entail substantial administrative costs to collect, process, and verify the data. That might also be true of the income approach, although it would

__________________

6This discussion focuses on which households are eligible for assistance, but policymakers also will have to decide which properties are considered when determining a household’s eligibility. One option would be to consider only primary residences.

7A definition of income specifies the components of income that are counted. Household membership must also be defined. For more information about definitions used to determine SNAP eligibility, for example, see htttp://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/eligibility.

not require data on housing expenses.8 In contrast to the income and housing cost approaches, the capped premiums approach requires no additional data beyond what is needed to calculate premiums.9 That offers the potential for administrative cost savings. However, unless income is considered as an additional eligibility criterion (as discussed below), the capped premiums approach has no means testing that would target assistance to those who would have the greatest need according to the income and housing cost approaches (the issue of whether assistance should be more specifically means tested and the issue of administrative burden and costs are discussed later in this chapter).

After the selection and full specification of a cost burden measure, several questions remain to be answered by policymakers. Will any households that are not cost burdened be eligible for assistance? If so, how will they be identified? Will all cost-burdened households receive assistance? If not, what additional criteria will be used to target assistance? Additional criteria that could be used to expand or restrict eligibility for assistance are discussed next. As policymakers consider these or other criteria, one issue arises consistently: If funds available for assistance are largely fixed, policymakers who are specifying eligibility criteria face a tradeoff between providing greater assistance on average to a smaller number of eligible households and providing less assistance on average to a larger number of eligible households.10

Eligibility Based on Loss of Pre-FIRM Subsidized or Grandfathered Premiums

Pre-FIRM subsidies and grandfathering have served as forms of assistance to policyholders, lowering premiums and making flood insurance more affordable. One possible eligibility criterion for a new assistance program would make assistance possible only for those policyholders who previously paid pre-FIRM subsidized or grandfathered premiums (perhaps as of a specified date)—that is, policyholders who previously were receiving assistance. Alternatively, any household that was eligible for a pre-FIRM subsidized or grandfathered premium (as of some date)—regardless of whether it purchased insurance—could be eligible for assistance under a new program. Because pre-FIRM subsidies and grandfathered premiums

__________________

8The income and housing cost approaches are familiar to housing program administrators and might offer opportunities to link and potentially integrate flood insurance assistance with existing housing assistance programs.

9If a household is losing a pre-FIRM subsidy, data on the household’s property that had not been previously obtained may be needed to calculate the risk-based flood insurance premium.

10If funds are not limited, assistance costs may rise as the number of households eligible for assistance grows.

were offered to households without regard to income or housing expenses, limiting eligibility for a new assistance program to households that received or could have received pre-FIRM subsidies or grandfathered premiums would probably prevent some households from receiving assistance even though they would be cost burdened by risk-based premiums according to the income or housing cost approaches.

Although payment of or eligibility for a pre-FIRM subsidized or grandfathered premium might be used as a criterion to reduce the number of flood insurance cost burdened households that are eligible to receive assistance, such a criterion could also be used to expand the number of households that are eligible for assistance. For example, in addition to households that are cost burdened by flood insurance, any households that are not cost burdened but previously paid pre-FIRM subsidized or grandfathered premiums might be made eligible for assistance. A broadening of the eligible pool in this way could be justified by, for example, interpreting a curtailing or elimination of pre-FIRM subsidized or grandfathered premiums as a breach of an implied promise to owners of NFIP-insured properties who had counted on continuation of subsidized or grandfathered premiums (for themselves and for potential buyers of their properties), especially those who were subject to the mandatory purchase of flood insurance.11

Eligibility Based On Requirement To Purchase Flood Insurance

A household that is subject to mandatory purchase of insurance and that pays a pre-FIRM subsidized or grandfathered premium, has three choices when its premium rises to a new risk-based rate: discontinue compliance with the purchase requirement, continue compliance and pay the higher premium, or purchase a different quantity of insurance to the extent a bank authorizes it (higher deductible and lower limit).

To encourage continued compliance, policymakers might choose to target assistance to households that are flood insurance cost burdened and are required to purchase flood insurance. Such targeting of assistance might encourage compliance of some households that were not previously compliant. At the same time, households that purchased flood insurance voluntarily but are not eligible for assistance might drop their coverage if premiums rise.

__________________

11Even with this interpretation, policymakers may choose to limit the duration (and amount) of assistance that would be provided to such households. Policymakers may also specify that eligibility for assistance based on previous eligibility for pre-FIRM subsidized or grandfathered premiums would cease when a property is sold. Potential restrictions on eligibility for assistance or limitations on assistance amounts based on the duration of assistance are discussed further under “How much assistance will be provided?” (Decision 4).

Eligibility Based on Housing Tenure

Housing tenure refers to whether a household owns its home or rents. As noted previously, the share of income spent on housing by the median renter is over 38% percent, so increases in rent due to higher flood insurance premiums passed on by landlords (or higher premiums for personal property coverage) might create a substantial need for financial assistance to renters. However, targeting assistance only to homeowners has advantages. First, in addition to the immediate costs of higher premiums if pre-FIRM subsidies and grandfathering are eliminated—costs that are borne by homeowners and potentially renters—homeowners are affected when costs of increased premiums are capitalized into property values and lower resale prices.12 Second, limiting eligibility to homeowners may ease the administration of an assistance program that uses the housing cost approach to measuring the cost burden of flood insurance. It is relatively straightforward conceptually (even though burdensome to policyholders and administratively expensive) to identify flood insurance cost burdens for homeowners.

The targeting of assistance for renters would require developing estimates of the percentage of rent attributable to the cost of flood insurance passed forward to tenants.13 It will be especially challenging when renters are residents of multi-family buildings and a single premium is paid for the entire building. There are over 233,000 such buildings across the nation (about 25% of all pre-FIRM polices; see Chapter 5), and there are areas, especially urban locations, where there are likely to be concentrations of such buildings. Although the most straightforward approach would be to base assistance on total rental housing costs, such an approach would probably provide assistance for housing costs that have nothing to do with flood insurance premiums. Some states that have property tax circuit breaker programs14 provide property tax assistance to renters on the basis of the

__________________

12Resale prices may reflect the market’s assumptions regarding future premium levels. Eliminating a premium subsidy reduces resale value by the increment of value that reflects the subsidy. However, the economic impact on the seller is essentially the same as the impact of the future higher insurance premiums if the property had not been sold. The former is merely the capitalized value of the latter. In short, the so-called asset value shock is not different from the shock of higher premiums extending into the future. In contrast, in the absence of a sale, reduced property value.

13Renters can pay directly for flood insurance covering their personal possessions and already pay NFIP risk-based rates for contents coverage. However, they still would be affected by elimination of pre-FIRM subsidized rates and grandfathering provisions if increased premiums on structures were passed along as rent increases.

14Programs in which state governments provide property tax refunds to those whose property taxes are deemed too high. For more information see http://www.cbpp.org/cms/?fa=view&id=51.

assumption that a portion of their rent (typically 15-35%) is attributable to property taxes paid by landlords (Anderson, 2012). Similar reasoning could be used in providing assistance to ease flood insurance cost burdens borne by renters, but it would still require much analysis to determine the percentage of the rent that is attributable to flood insurance costs.

Eligibility Based on Household Income

As in some of the housing assistance programs described earlier, policymakers designing a flood insurance assistance program might seek to provide greater assistance to households of low or low-to-moderate income. Although policymakers can use the income approach to measuring cost burden to target assistance to any particular income class (such as households whose income is below 50% of the area median), they can do that with the other two cost burden approaches only by making income a separate eligibility criterion or by basing assistance amounts on income (see Decision 4 below: How Much Assistance Will Be Provided?). As noted previously, the capped premiums approach takes no account of household income, whereas the housing cost approach identifies as cost burdened households whose housing costs, including flood insurance, exceed a specified percentage of their income. With both approaches, eligibility for assistance among cost-burdened households could be further restricted to households that, for example, have low-to-moderate incomes.15

Eligibility Based on Mitigation

FEMA-approved methods of mitigation of flood risks to insured properties could be used to reduce insurance premiums (discussed in greater detail in Chapter 7). To reduce any disincentive to mitigate and, more generally, encourage mitigation, the performance of specified mitigation activities could be a requirement for eligibility to receive flood insurance assistance.16 As will be discussed in Chapter 7, the reduction in risk attributable to mitigation could be reflected in reduced premiums.

_____________

15If such a provision were adopted, administrative burden and costs could be reduced for some households through the use of adjunctive eligibility, that is, automatic eligibility for flood insurance assistance based on participation in another means tested assistance program, such as SNAP.

16Assistance for undertaking mitigation activities is discussed under Decision 2: What Assistance Will Be Provided? and in Chapter 7.

Eligibility Based on Community Characteristics

All the eligibility criteria discussed so far pertain to characteristics of individual households—whether the household is cost burdened, whether it has paid a pre-FIRM subsidized or grandfathered premium, and so forth. However, community characteristics also can be considered as eligibility criteria for individual households, restricting or expanding the eligible pool.17

One criterion that would reflect a concern for the effects of increased premiums on neighborhood vitality would be the prevalence of households whose premiums become cost burdensome when pre-FIRM subsidies and grandfathering are eliminated. Households that benefitted from such subsidies and grandfathering might be especially prevalent in some communities whose vitality could be threatened by the elimination of pre-FIRM subsidies or grandfathering. Policymakers could make all households in a community eligible for assistance if a specified (or higher) percentage of them would likely be eligible on the basis of their individual circumstances. In addition to protecting the vitality of a community, this eligibility criterion could reduce administrative burden and costs by removing the need to establish eligibility of every household, as discussed further under Decision 6: How Will an Assistance Program Be Administered?18

Another potential eligibility criterion could be the engagement of state and local governments in certain mitigation activities. Activities that have been or could be undertaken are discussed in detail in Chapter 7. This criterion could provide an incentive to undertake mitigation and promote cost sharing of efforts to reduce premiums and enhance the affordability of flood insurance (an issue discussed under Decision 5: Who Will Pay for Assistance?).

As suggested by this discussion, household and community characteristics can be used jointly to determine eligibility. For example, assistance could be provided to cost-burdened households only if they are in communities where the prevalence of cost-burdened households is high, concentrating assistance where it is judged to be most needed.

__________________

17Availability of NFIP flood insurance to property owners in a community is already conditioned on the community’s willingness to adopt and enforce various regulations to reduce vulnerability to flooding (for example, requirements to elevate new construction to the elevation of the 100-year flood).

18National school meals programs have special provisions that allow districts to serve free meals to all students in schools in low-income areas without certifying the eligibility of individual students for free meals.

Decision 2: What Type of Assistance Will Be Provided?

In addition to specifying criteria for determining whether a property owner or renter is eligible for assistance, policymakers must identify the form(s) in which assistance will be provided. Two broad types of assistance that might be made available to individual property owners or renters are

- Premium assistance that directly reduces the amount that a property owner or renter pays for flood insurance,

- Mitigation assistance that indirectly reduces the amount that is paid by helping a property owner to finance mitigation activities that reduce risk in ways that will be reflected in a lower insurance premium.

Decision 3: How Will Assistance Be Provided?

Premium or mitigation assistance can be delivered in many ways. Discussion of a variety of options is presented in Chapter 7; the focus here is on application burden and administrative costs of an assistance program. Providing premium assistance at the time of purchase, for example, might ease the application burden on the property owner relative to some other modes of delivering assistance. However, with any mode of delivering assistance, administering premium assistance to a specific group of property owners might entail substantial costs if extensive efforts are required to verify eligibility. That might suggest providing assistance through an existing administrative process. For example, providing premium or mitigation assistance through an income tax credit could rely on existing tax compliance activities but would require changes in the tax code, tax forms, and return processing procedures. It also would impose a burden on property owners who are eligible for assistance but are not otherwise required to file tax returns.

Decision 4: How Much Assistance Will Be Provided?

In addition to determining who is eligible for assistance, policymakers must specify a formula or algorithm for calculating the amount of assistance for which an eligible property owner (or renter) qualifies. Different formulas or algorithms might be specified for premium and mitigation assistance. The methods selected to calculate assistance will reflect normative standards regarding the expected contribution of the property owner toward purchasing flood insurance or paying for mitigation and how the property owner’s personal circumstances (such as household income and

housing expenses) affect the amount of assistance provided. Choices also will reflect the consideration of tradeoffs. For example, providing more generous assistance will make flood insurance more affordable and potentially increase takeup rates (see Chapter 4 for further discussion). However, it will also increase the total budget for the assistance program (for a given number of property owners receiving assistance).

The central input into a formula for calculating, for example, the amount of premium assistance might be the same measure of cost burden that is used to determine eligibility for assistance. If so, the amount of assistance could equal the entire cost burden or some proportion of it, where the proportion might vary with the property owner’s household income or according to whether the property owner is required to purchase insurance, has undertaken mitigation activities, or is elderly or disabled. Concerns about burden or the administrative costs of providing assistance might lead to the specification of a guaranteed minimum amount of assistance provided to an eligible property owner. The minimum could be a fixed dollar amount, or a percentage of the NFIP risk-based premium. The amount of assistance might also be capped, for example, at a fixed dollar value, a percentage of the NFIP risk-based premium, or the difference between the NFIP risk-based premium and the premium previously paid under pre-FIRM subsidy or grandfathering provisions.

A related design question is the amount of assistance to provide if housing costs excluding flood insurance exceed whatever affordability standard has been adopted (for example, a household is cost burdened if housing costs are greater than 30% of income). In that case, the following questions must be addressed: Will the flood insurance assistance program be responsible for eliminating any of the cost burden that is not due to flood insurance? If a household is cost burdened in the absence of insurance, will the amount of assistance equal the entire NFIP risk-based premium? Or will the amount of assistance be capped if it is determined that the household could afford more expensive housing than the standard? If many households are in this situation, the eligibility criteria and assistance formula could be reviewed to assess, for example, whether the standard is too generous or does not appropriately reflect geographic differences in expenses or whether the measure of income used understates available resources.

In determining the amounts of assistance that will be provided, additional questions that arise pertain to the duration of assistance. Will assistance be provided indefinitely to a property owner who remains eligible under whatever criteria have been specified? Or will assistance be time limited? Will the formula or algorithm for calculating assistance amounts

reflect the number of years for which assistance has been provided to a property owner, potentially reducing the amount of assistance over time?19

In addition to considering whether to limit eligibility or assistance amounts on the basis of the duration of assistance, policymakers will need to consider how year-to-year variation in the amount of assistance might affect a property owner’s decisions to purchase flood insurance and maintain coverage. For example, should the eligibility criteria and formula or algorithm for determining assistance amounts be specified so that the amount of assistance provided to a property owner is relatively stable or, changes in a highly predictable way? In addition, how can such stability or predictability be obtained while maintaining a high degree of accuracy in targeting assistance to those most cost burdened by flood insurance premiums?

In deciding how much assistance will be provided to eligible property owners, an important question is whether premium or mitigation assistance will be an entitlement or will be limited by the amount appropriated by Congress. If assistance is considered to be an entitlement, anyone eligible will receive the full amount of assistance for which they qualify. If assistance is not an entitlement, it may be necessary to limit the amount of assistance provided so that the total for all recipients does not exceed what is available. One possible approach in such a case is a priority system that provides assistance to property owners on the basis of severity of the cost burden, income, whether the purchase of insurance is mandatory, elderly or disabled status, or other household or community characteristics; property owners at higher priority would receive assistance before property owners at lower priority. An alternative would be a pro rata reduction in all assistance awards that is based on the expected shortfall in available funds.

Making decisions about each of those matters may require development of formulas and algorithms that balance the different considerations in offering aid. With such complexity, it can be important to maintain as much “smoothness” as possible in the formula or algorithm (Zaslavksy and Schirm, 2002). Ideally, property owners facing similar circumstances receive similar amounts of assistance, and situations in which one property owner receives substantially less assistance than a property owner who has only slightly less income or slightly higher housing expenses and roughly the same flood insurance premium are avoided.

__________________

19Limitations on the duration of assistance could also be specified through eligibility criteria. For example, a property owner could become ineligible for assistance after a specified number of years or after receiving a specified total amount of assistance.

Decision 5: Who Will Pay for Assistance?

The decision about who pays for assistance entails two main choices. The first is the degree to which costs are borne by federal taxpayers versus NFIP policyholders who do not receive assistance but pay for assistance to others through a cross-subsidy (see Chapter 3). The second is the degree to which aid program costs are borne broadly (for example, nationally) versus more locally (by states, tribal nations, or communities) or are shared by federal and local governments.

One consideration in making the first choice is the capacity of policy holders who do not receive assistance to pay for assistance to other policyholders through premium surcharges or implicit loadings. That capacity will fall as the fraction receiving assistance or the average amount of assistance rises. A consideration is whether some who do not receive assistance might drop coverage if their premiums increase substantially to pay for this assistance. If the federal taxpayer is going to be paying for assistance, such payment will require congressional authorization and appropriation(s).

In determining how much of assistance costs to allocate nationally, versus locally, a relevant consideration is the incentive for local authorities to undertake mitigation efforts that broadly benefit residents in the community. There is a greater incentive to undertake such efforts if a greater share of the assistance costs is to be borne locally, in which case a local government can reduce its costs for assistance by undertaking mitigation activities that reduce premiums and the need for assistance.

Decision 6: How Will an Assistance Program Be Administered?

In administering a program of targeted assistance, policymakers must identify which entities are responsible for determining whether a property owner is eligible and how much assistance that property owner will receive under the established eligibility criteria and assistance formula or algorithm. In addition to the broad decisions that must be made about how to determine, for example, eligibility for assistance, many more detailed decisions will need to be made, including how to define a household, how to define income, how to treat a household’s assets in determining its need for assistance, and whether to take into account the effects on unusually high nonhousing expenses (such as medical expenses) on household resources. Policymakers also will have to determine how the necessary data will be obtained from households (for example, through an application for assistance).

To enhance program integrity, policymakers may also specify procedures for monitoring the accuracy of eligibility and assistance award determinations, and designate an entity that will perform such functions.

Candidates for those various administrative activities include FEMA; HUD; state, local, and tribal government organizations; and private insurers that administer the write your own (WYO) flood insurance policy program (see List of Terms).

Another important consideration in determining how to administer one or more assistance programs is the balance between maximizing access among those who are eligible and minimizing administrative costs. Striking such a balance requires the tradeoff between the accuracy of targeting assistance and the cost of administration. Generally, to target means tested assistance, detailed data are needed on income, expenses, and other characteristics of individual households. Obtaining and processing such data are burdensome and costly. These activities can be prone to error, and it might be prudent to verify the accuracy of the data (on at least a sample basis), which entails another administrative cost.20 Strategies that seek to minimize data needs include community eligibility options and homeowner eligibility based on extant public data.

One community eligibility option would be to make all homeowners in a community eligible for assistance if, for example, the community’s poverty rate is sufficiently high, the median income is sufficiently low, or many homeowners that previously paid pre-FIRM subsidized or grandfathered premiums.21 This approach will sacrifice some accuracy in targeting, providing assistance to homeowners who are not flood insurance cost burdened based on the basis of their individual circumstances and failing to provide assistance to cost-burdened homeowners in communities that are not eligible for assistance.22 In addition, even if a community eligibility approach identifies exactly the homeowners to whom policymakers wish to provide assistance, a remaining challenge is to determine the amount of assistance that will be provided to each individual homeowner without data specific to each homeowner. Community eligibility also raises the issue of whether to define a community on the basis of census geography (described in Chapter 5) or jurisdictional boundaries. If, instead, eligibility were based on publicly available data on characteristics specific to individual homeowners, such

__________________

20For SNAP, a quality control system has been developed to monitor the accuracy of eligibility and benefit determinations. See http://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/quality-control.

21For such a community, it is assumed that the eligibility rate of individual homeowners would be sufficiently high to make it cost-effective to dispense with individual eligibility determinations; that is, the administrative cost savings would exceed the costs of providing assistance to the relatively few homeowners who would not be eligible on the basis of their own circumstances. As noted previously, national school meals programs have special provisions that allow districts to serve all students in schools in low-income areas without certifying student eligibility. This practice allows the districts to process fewer applications and thereby reduces administrative costs.

22If an entire community is ineligible for assistance, eligibility could be determined household by household, which would incur higher administrative costs.

as assessed property values, a homeowner could be eligible for assistance if their property values were less than a specific dollar amount or below a particular percentile for the community. Of course, if that criterion does not reflect a given homeowner’s flood insurance cost burden and thus the need for financial help, assistance will not be accurately targeted.

Clearly, strategies that seek to minimize data needs have limitations. Nonetheless, some consideration of those approaches is warranted if for no other reason than to provide context for considering limitations of and justification for using more complex and costly approaches. In addition, it might be possible to use streamlined eligibility procedures in some areas, and more complex procedures elsewhere to strike a balance between the objectives of targeting and the goal of minimizing administrative costs.

This chapter discussed concepts of affordability and presented a decision framework for designing assistance programs to make flood insurance more affordable—the affordability framework called for by recent legislation. The discussion of affordability describes three potential measures of the cost burdens imposed on households by NFIP premiums. In HFIAA 2014, Congress proffered a capped premiums measure, and suggested that a premium exceeding 1% of the insurance coverage is burdensome and thus unaffordable. A second measure of cost burden uses an income test, and identifies a flood insurance premium as unaffordable for any household whose income is below a specified threshold. A third measure considers not only a household’s income but also its housing costs, and assesses the ratio of housing costs to income when the NFIP premium is added to other housing costs. If the ratio exceeds a specified value, the flood insurance premium is regarded as cost burdensome and therefore unaffordable. Those three measures reflect different subjective judgments about the cost burden of flood insurance premiums and about whether such premiums are affordable. More generally:

- There are no objective definitions of affordability. Although the concept is substantially subjective, the choice of a definition can be informed by research evidence and experience in administering means-tested programs that, for example, provide housing and other assistance.

- There are many ways to measure the cost burden of flood insurance on property owners and renters. Policymakers have to select which measure(s) will be used in the NFIP for targeting assistance to enhance flood insurance affordability. This decision is not amenable solely to technical analysis.

Choosing a cost burden measure, however, is not the only policy choice in designing a financial assistance program. The many considerations, and some policy options, in designing a means tested assistance program for an affordability framework are summarized in Figure 6.1.

- To design a program that provides assistance in making flood insurance more affordable to NFIP policyholders, policymakers face several choices, including who will receive assistance, what type of assistance will be provided, how assistance will be provided, how much assistance will be provided, who will pay for assistance and how an assistance program will be administered.

Not surprisingly, tradeoffs arise in making policy choices. For example, providing assistance to more policyholders will require cutting the average amount of assistance provided if the total cost of the assistance program is to be held steady. If instead, more generous assistance is provided, insurance takeup rates might increase, but the total cost of the assistance program might also increase and incentives to mitigate might decrease. As another example, in specifying eligibility criteria for assistance, more specific and accurate targeting of assistance based on policyholders’ characteristics will require policyholders to provide more personal data, and this will increase the burden on policyholders and raise administrative costs of processing and verifying data provided.

- The decisions that must be made in designing an affordability assistance program entail tradeoffs that will have to be resolved by policymakers.

This page intentionally left blank.