4

Coordination of a Community Response

Highlights and Main Points Made by Individual Speakers and Participants1

- There is a need to define what is meant by a “true collaboration” across sectors. Collaboration depends first on understanding an organization’s partners, then making commitments, communicating, cooperating, and coordinating. (Jones)

- Creating an all-volunteer registry for managing volunteer inflow during a disaster event can allow for better accessibility across jurisdictions and states. (Hick)

- Developing a system that allows nongovernmental organizations to target their services and resources to local communities through a type of “resource catalog” can simplify the procurement process for state and local health departments during a disaster. (Hick, Prats)

- Loss of Hospital Preparedness Program funding has threatened the regional partnerships and coordinating entities built over the previous decade. (Prats, Upton)

- Elements of successful coordination following the 2014 chemical spill in West Virginia include promoting interagency communication, building trust and relationships, holding mutual interests and objectives, and developing local decision-making capacity. (Gupta)

As disasters have continued to occur throughout the United States and the greater global community, an increasing number of organizations have realized a role during disaster response and recovery to promote healthier outcomes in communities and regions. Successful response to a large-scale disaster includes coordination horizontally and vertically

________________

1This list is the rapporteurs’ summary of the main points made by individual speakers and participants, and does not reflect any consensus among workshop participants.

within and across the public sector. Additionally, partnerships between the public and private sector (cross-sector collaborations) have become more common and help to serve a greater portion of the population across cultures, geographic locations, age, and other demographics. This chapter discusses the importance of promoting cross-sector collaborations to enhance information management and communication, effectively use volunteers, build sustainable coalitions, and coordinate streamlined health messages to the public.

PROMOTING CROSS-SECTOR COLLABORATION

Michael “Mac” McClendon, the director of the Office of Public Health Preparedness of the Harris County Public Health and Environmental Health Services in Texas, spoke of the need to involve leadership of health care organizations to promote cross-sector collaboration. He noted that many “C-suite” level executives may not be concerned about resources and planning for disaster until it occurs to their facility or within their region. Receiving support from the top level of leadership at hospitals can be influential, he commented, in promoting the importance of preparedness activities within an institution, including the allocation of funding, staffing, and support. To assist in overcoming this challenge, participants suggested using business-oriented channels such as chambers of commerce or trade groups to relay the importance of preparedness resources. Osborn noted that this approach is currently active in Minnesota through partnerships with the Minnesota Hospital Association.

Defining and Understanding the Meaning of “Collaboration”

The key to cross-sector collaboration is ensuring that partnerships are sustainable before, during, and after disasters. Ana-Marie Jones gave an overview of cross-sector collaboration from her experience as executive director of Collaborating Agencies Responding to Disasters (CARD). CARD is a nonprofit agency, based in Oakland, California, that was created in the wake of the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake by local nonprofit agencies to address the preparedness and response needs of service providers. The Loma Prieta earthquake demonstrated that despite great effort and billions of dollars invested, traditional disaster response agencies simply could not address all of the emergency preparedness,

planning, and response needs of an increasingly diverse society, Jones said. CARD complements traditional disaster response agencies by providing safe, accessible, emergency services tools and programs designed for nonprofits, faith agencies, related service providers, and the communities they serve.

Jones pointed out that the concept of “collaboration” across sectors has long been assumed, expected, advocated, romanticized, and even scapegoated in the face of failure. True collaboration, she claimed, remains largely misunderstood. Jones asserted that most of the struggles and failures around collaboration stem from unrealistic expectations and a lack of understanding of the component pieces involved. Collaboration is made all the more insurmountable because of silos created by nonprofits, academia, utilities, health, government, and business. The “people” involved make or break collaboration, with personal and institutional relationships being essential. Collaboration depends first on understanding an organization’s partners, then making commitments, communicating, cooperating, and coordinating.

In terms of lessons learned, forming true collaborations requires at least eight elements, observed Jones:

- Choose to collaborate: enter a collaboration with eyes wide open by making the collaboration an intentional act, alert to its pitfalls, costs, and multiple steps in a pathway.

- Be honest: be brutally honest because without honesty there is no trust between partners; acknowledge the weaknesses of each collaborating partner.

- Celebrate/leverage differences: understand and honor each collaborating organization’s diversity as a genuine competitive advantage.

- Stay focused on common goals, values, and needs: do not deviate from these shared purposes. Avoid veering off into goals that only the strongest voice wants.

- Protect your collaborators from idiosyncrasies of one’s own bureaucracy: when entering a collaboration, it is essential to know each collaborating organization’s pitfalls, and then actively protect collaborative partners from experiencing them.

- Create micro-successes: most organizations cannot sustain a long process to reach a goal; each collaborating organization has to break down the long process into tiny steps along the way for which they can achieve success.

- Embrace technology: use technology to create an electronic “place” (e.g., Google Docs, Dropbox, or “the Cloud”) that every collaborating partner can access.

- Seek clarity: spell out the path for all collaborating partners and agree on the level and depth of each organization’s responsibilities, procedures, and communication standards.

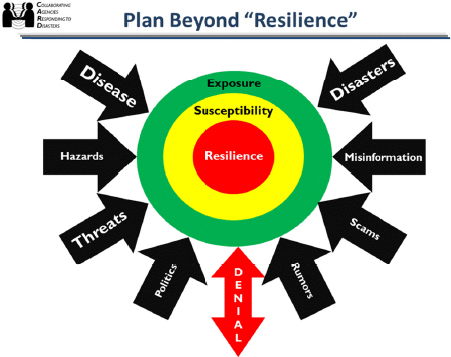

Especially in a regional response or planning effort, Jones said it is important to balance the needs of each community, and include diverse perspectives within and among urban, rural, and frontier settings. This is essential for successful day-to-day partnerships and the operation of the incident management structure with multiple jurisdictions involved. Finally, with a hint of disaster risk reduction concepts, Jones urged participants to “plan beyond resilience.” She said the emergency management and health preparedness field should look beyond just helping communities “bounce back” after disasters and spend more time thinking about how to reduce exposure to the disaster and work across communities to make them less susceptible to the effects (see Figure 4-1).

Private-Sector Engagement

Kellie Bentz, the team lead of global crisis management at Target Corporation, explained that great strides have been made in forging public–private partnerships to coordinate activities during a disaster. Public–private partnerships were given a boost when the national emergency operations center (EOC) created a seat at the table for Volunteers Active in Disaster (VOAD). They were also given additional support through Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA’s) creation of a National Business Emergency Operations Center (NBEOC),2 a virtual organization that serves two-way information sharing between public- and private-sector stakeholders in preparing for, responding to, and recovering from disasters.

Bentz also spoke about her corporation’s robust system of global crisis management. Target created a centralized corporate command center supporting a crisis management team that coordinates internally (nearly 1,800 stores and 37 U.S. distribution centers nationwide) and coordinates with public-sector partners through public–private

________________

2NBEOC was first activated in 2012 during Superstorm Sandy. For more on NBEOC, see http://www.fema.gov/media-library-data/20130726-1852-25045-2704/fema_factsheet_nbeoc_final_508.pdf (accessed October 13, 2014).

partnerships. If the crisis involves a disease epidemic, the command center turns for guidance to its medical director or medical team; if the crisis is a hostage situation, the command center turns for guidance to its corporate security team. The command center maintains weather tracking through real-time weather alerts and 24/7 access to a consulting meteorologist. The command center also conducts tracking of its 1,500 employees who are traveling domestically on any given day and 600 employees who are traveling globally, some of whom are using corporate aircraft. Target also has at its disposal more than 100,000 surveillance

FIGURE 4-1 Planning beyond “resilience” frameworks for cross-sector collaboration.

SOURCE: Jones presentation, March 26, 2014.

cameras, with live and archived video. When asked, Target gives public-sector partners access to these cameras. As a real-life example of public-sector partners needing surveillance cameras, Gary Schenkel, executive director of the Chicago Office of Emergency Management and Communication (OEMC), described their cross-sector coordination during the Chicago Marathon each year. OEMC maintains a public–private partnership using the Facility Information Management System

(FIMS), which houses building plans, emergency points of contact, and emergency operations plans for buildings throughout the city. They are made accessible to OEMC and the police and fire departments during emergencies. The city also tapped into FIMS to cover the Chicago Marathon. Because the city’s existing camera system did not cover all 26.2 miles of the race, FIMS coordinated with the private sector to take over private cameras so that the entire route could be surveyed by emergency managers. Bentz reiterated Schenkel’s message, saying Target’s command center is run by a crisis management team that works with the private sector, public sector, and its internal staff to create a common operating picture. The command center establishes all emergency-related communications to Target’s employees. The crisis management team seeks to build relationships with public-sector partners before disaster strikes.

During preparations for Superstorm Sandy in 2012, 265 Target stores were in the path of the storm, Bentz said. A challenge for a company spread across a region like this is trying to plug in to all of the local operating EOCs and understanding priorities. However, Bentz mentioned that FEMA’s recently developed NBEOC was activated during the Superstorm Sandy response and was able to consolidate all incoming information from across the country into an extremely useful report. Because of this, along with other data provided through NBEOC such as a regional map of active utility power, they were able to quickly prioritize generators and other resources to the stores and communities that needed them.

MANAGING VOLUNTEERS ACROSS A REGION

Cross-sector collaborations nearly always involve the activities of volunteers. Captain Robert Tosatto, director of the Medical Reserve Corps (MRC) program now housed within Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR), delivered an overview of volunteerism. He pointed out that in 2012, 64.5 million Americans (26.5 percent of the U.S. population) volunteered, generating 7.9 billion hours, worth $175 billion. The largest share of volunteers served in the religious sector (34.2 percent), followed by the educational sector (26.5 percent), social services (14.4 percent), and health (8.0 percent). Tosatto said whether or not a volunteer has a positive experience depends on the quality of volunteer management practices, that is, whether volunteers

are organized, used appropriately, comfortable, and engaged in the roles in which they are placed.

There are at least three common misperceptions about volunteers. The first misperception, said Tosatto, is that they cannot be counted on to do the work. The more that is done to engage volunteers, he noted, the higher the likelihood is of them responding when needed. The second misperception is that volunteers are amateurs—unskilled, undisciplined, and unprofessional. In fact, many bring expertise that might otherwise be inaccessible, such as veterinary training, pharmacy management, or mortuary expertise. Additionally, volunteers’ enthusiasm often carries the dividend of motivating paid staff. Volunteers are committed to recovery of the community because it is often the community where they live. The third misconception is that volunteers are free. This is not the case, as there are certainly costs associated with their training, supplies, equipment, and management, said Tosatto.

There are three general types of volunteers. The first is “generic” versus skill-based volunteers. The second is planned versus spontaneous, and the third is affiliated (e.g., American Red Cross, MRC) versus unaffiliated. Spontaneous unaffiliated volunteers—people who just show up to volunteer during an emergency without any pre-registration or notification—are the most problematic. Emergency managers must prepare for them with just-in-time training, rapid screening, rapid background checks, and rapid verification of credentials, especially for health care professionals. While adding these processes during a stressful response phase seems cumbersome, even spontaneous volunteers could be a critical support piece of the response and should not be overlooked. It is incumbent upon emergency managers to have a system in place for volunteer management, according to Capability #15 of the PHP (Public Health Preparedness) Capabilities, published in March 2011.3 This Capability specifies four functions: coordinate; notify; organize, assemble, and dispatch; and demobilize volunteers.

The Medical Reserve Corps

Tosatto then turned to the MRC, a national network of medical and public health volunteers sponsored by ASPR in support of strengthening public health, improving emergency response, and building community resilience. There are some 200,000 MRC members in nearly 1,000 units

________________

3See http://www.cdc.gov/phpr/capabilities/DSLR_capabilities_July.pdf (accessed April 10, 2014).

nationwide. About 90 percent of the U.S. population lives in jurisdictions served by an MRC unit, Tosatto added. Generally, each unit has a distinct composition that is based on local needs for integrating medical volunteers within existing programs and resources. All MRC units have a particular organizational structure, pre-identified members, verified professional licensure/certification, and trained/prepared volunteers. (However, as discussed later in this chapter, their skill sets are not standardized across units.)

When a disaster strikes, state medical and public health volunteers come into play through the Emergency System for Advance Registration of Volunteer Health Professionals (ESAR-VHP) system. ESAR-VHP is a national network of state-managed registries that allows health professionals the chance to get their licenses and credentials verified before a disaster. The program is also administered under ASPR. Thus, in regional disasters, emergency managers usually have two sources of medical volunteers at their disposal, MRC and those in ESAR-VHP.

Including Nongovernmental Organizations (NGOs)

Volunteers from NGOs are also key to emergency response, noted Bruce Clements, preparedness director for Texas State Health Services. The Salvation Army is usually counted on to set up meals, while the American Red Cross is usually relied on to open and staff shelters. Clements said that in Austin, most of the faith-based NGO coordinating is done under one entity called the Austin Disaster Relief Network, which combines volunteers from hundreds of churches statewide, allowing coordinators to allocate volunteers to needed areas that may have been without help. He added that Texas has an NGO representative at the state EOC who acts as a liaison for local and regional NGOs, providing transparent coordination among state agencies leading Emergency Support Function (ESF)-6 and ESF-8 functions. This can also be used as an entry point for NGOs coming into the system.

BUILDING SUSTAINABLE COALITIONS AND COLLABORATIONS

The most significant challenge to cross-sector collaborations is to sustain collaborations during “peace time,” that is, the period between disasters. Rosanne Prats, the executive director of emergency

preparedness at Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals, warned of loss of collaborations with ongoing cuts to federal disaster response programs. Many public disaster agencies have lost key staff, she said, and are scrambling with fewer staff to maintain public–private partnerships. She added that the entire edifice of a regional response, which has been built over the past decade through dedicated funding and programs, is under threat unless new approaches are devised to sustain these regional cross-sector collaborations. For example, funding for the Hospital Preparedness Program (HPP), which is administered by ASPR, has been dramatically reduced in recent years and continues to be under threat of further reduction. The cooperation of hospitals and health care coalitions is needed in terms of sending staff to participate in the regional planning process, supporting full-scale and tabletop exercises, and encouraging training. Loss of federal funding translates to losing leverage to show hospital leadership there is commitment to regional preparedness at the federal level and makes it difficult to ensure that hospitals contribute to important disaster planning elements.

Prats added that collaborations are sustainable as long as they operate through institutional relationships that are independent of individuals. John Hick of Hennepin County Medical Center noted that the role of large NGOs being engaged in preparedness activities, including full-scale and tabletop exercises, is one way for cross-section collaborations to remain intact. Engagement in one preparedness activity generally motivates engagement in other disaster-related activities. Preparing for one threat, in short, helps to prepare for others. Using preexisting relationships as a way to connect with new agencies was highlighted by Aubrey Miller, senior advisor at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS). He said NIEHS relationships with academic centers and other grantees across the country opened up a network of opportunities to build relationships with NGOs that want to contribute to the cause, whatever that might be at the time. Miller said building those relationships ahead of time, and having the ability to tap into those resources at a moment’s notice, will help accelerate response time. Adding to this, Jim Craig of the Mississippi Department of Health called for a long-term, sustainable process for developing models for NGO relationship building. So often in the past, he said, short-term capabilities have been the focus, and the models and relationships disintegrate time and time again.

Coordinating Messages to the Public

The chemical spill in West Virginia in 2014 was examined to identify some of the challenges in disseminating important health and safety information across a large region during a real event with uncertain health consequences. Rahul Gupta, executive director, Kanawha-Charleston Health Department, spoke about the accidental release in January 2014 of 10,000 gallons of the chemical methylcyclohexanemethanol (MCHM) and eight other chemicals into the Elk River. The contaminants were released upstream of the drinking water intake, treatment, and distribution center. Within hours of the spill’s detection, members of the public complained of a black licorice-like odor emanating from the water. At that point in time, little was known about the chemicals or their human health effects. The main toxin, MCHM, is a chemical used to wash coal and remove its impurities that contribute to pollution during combustion. Although no human data were available about MCHM, it is considered hazardous by the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) indicates that no MCHM should be detectable in drinking water. Simply finding information alone was a challenge, said Gupta, because there was so much unknown about the chemical and its health effects. There was not enough information available to know the full scope of the problem, nor ease the ensuing panic of the public.

Within hours of the spill, Gupta said the health department decided to launch an unprecedented “Do Not Use” (DNU) tap water order. This meant launching an exceptional health response to inform local residents and enforce closure orders for schools and businesses. The DNU order affected all 300,000 people served by the water utility across nine counties surrounding the river and the state capitol, Charleston. Two days after the DNU order was lifted and the water was deemed safe to drink, CDC advised pregnant women not to drink the water. The West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection also alerted the public that more chemical was released than was originally reported. At the same time, a second wave of illnesses occurred because the chemicals in the hot water storage tanks began to vaporize. The vapors condensed on the skin, leading to primary complaints of skin and mucosal irritation. Some people also reported migraines, nausea, vomiting, and respiratory tract symptoms. The water still smelled foul. These conditions created mistrust between the public health agencies and citizens, and propelled

many to avoid using the water that was deemed safe. Some participants commented that when multiple stakeholders are involved, common challenges in information sharing and dissemination include issues of message coordination and information access, resources and staffing, and message adaptability and customization for the target audience. Gupta explained that this large operation was organized by an interagency task force that included representatives from multiple levels: CDC, the Environmental Protection Agency, FEMA, the National Institutes of Health, the National Guard, the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection, West Virginia (WV) governor’s office, the WV-American Water Company, city and county governments, local boards of education, hospital systems, law enforcement, and local health departments. What became apparent through the response, he noted, was the importance of effective negotiation skills, and using those and credible science to inform decision-making capacity and mutual objectives among that many stakeholders.

Identified Challenges and Lessons

Gupta cited several other challenges following the incident, particularly issues with conflicting public messaging. “This resulted in issues of trust, communication, and negative perception of water safety within the community,” he said, while also noting the evolving role of social media in disaster management and how it can be leveraged as a means of digital surveillance. He suggested that it should absolutely be used when possible to see what is and is not working, and actions should be immediately changed, if needed, instead of simply waiting for an After Action Report to be released. He added that some of the other elements of successful coordination they found were promoting interagency communication, building trust and relationships, holding mutual interests and objectives, and developing local decision-making capacity.

To help ensure that public health information is up-to-date and included in broader communications, Gupta also suggested having a public health information officer provide daily talking points to municipal leadership, even if not requested. He also noted that legal and competing interests can create additional challenges that hamper decision-making following an incident, as may occur when economic decisions start to outweigh public health priorities. Several participants suggested that circulating a structured, short report periodically after

disasters, among all entities within the ESF-spectrum can improve awareness, inform about work being done, and provide an opportunity for dialogue.

Scientific Response Units

Captain Deborah Levy, chief of healthcare preparedness activity in the Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion at CDC, described CDC’s use of Scientific Response Units, which bring together technical experts in various fields to offer their expertise or develop guidance as an event unfolds. These units create a structured approach for incident management. Daily updates are released in a scheduled, consistent fashion to partners and media outlets so that data and information are disseminated at set times every day. Some participants noted that having a common structure to bring together silos of technical experts offers an opportunity to strengthen interagency partnerships and craft more consistent messages to the public.4 In addition, the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO) has developed risk communication tools5 to plan for an emergency, create effective messages, and interact with the community and the media during a disaster (NACCHO, 2014).

HIGHLIGHTED OPPORTUNITIES FOR OPERATIONAL CHANGES

Successful coordination of a regional emergency response continues to be a dynamic goal as more sectors and entities find themselves with a role to help prepare, respond, or assist in recovery of their communities. Nonetheless, several participants and speakers had additional ideas for improving the management of volunteers, easing the manner in which NGOs are brought into responses, and enhancing partnership structures to enable a more resilient region:

________________

4CDC’s Healthcare Preparedness Activity hosts stakeholder meetings with a “whole of community” approach and builds in partnership activities. For more resources on communication, outreach, and building partnerships, see http://www.cdc.gov/phpr/healthcare/tools-resources.htm (all websites listed were last accessed October 13, 2014).

5For risk communication tools, visit some of NACCHO’s Advanced Practice Center products: http://tinyurl.com/qf2dvt6, http://tinyurl.com/nbgaaum, http://tinyurl.com/nbko7ar, and http://tinyurl.com/p65wtfa (accessed October 13, 2014).

- Several participants commented that developing a structure for management of spontaneous unaffiliated volunteers could improve use of volunteers during an event and asked whether federal stakeholders could assist in development of a toolkit. Currently, there is no standardized method for managing spontaneous volunteers across organizations. Individual participants noted that by setting up a standard process of registering volunteers across organizations and allowing physical and virtual means of registration, prospective volunteers could be solicited across counties and integrated into existing volunteer databases. From here, their documented skill sets could be matched to the situational needs in different areas (Fernandez et al., 2006).

- Hick pointed to the need to develop a method for NGOs to identify services and resources they have available to communities, so when needed, regional and local leaders can reach out to them for those particular services, and multiple jurisdictions will not be counting on the same limited number of assets.

- Resource “typing,”—that is, categorizing what assets and specific types of personnel organizations can provide, and setting a basic minimum standard, can also help to manage expectations of what types of resources are immediately available. Prats saw a need for a better statewide “resource catalog” that describes the volunteer groups and associated skills, capabilities, and resources available before, during, and after a disaster. A standardized assessment for state and local authorities to use would be additionally valuable. Seeing the larger picture up front and knowing what is available can help state and regional authorities plan and coordinate the response better.

- Create a standardized capabilities framework for medical and public health volunteer response agencies, voiced Hick. Given that there are no recognized definitions for voluntary organization capabilities in a public health and medical response, sharing volunteers across jurisdictions can be challenging. Hick added that there are important variations within groups sometimes that should be known in advance. For example, one MRC unit in a state may have 100 volunteers and be able to give vaccinations, but another MRC in the same region may only have 20 volunteers and not have that immunization expertise.

-

Several participants suggested defining a research agenda on capabilities and expectations and developing a pilot categorization tool to optimize use and sharing of volunteers across organizations. This could be done in partnerships among groups such as the American Red Cross, MRC, and the National VOAD.

- Hick also emphasized creating better, more reliable systems monitoring that can be used consistently between partners when an incident happens. Some participants agreed that shared systems monitoring offered an easy information-sharing opportunity for broadening networks and accessing new data streams that could have significant importance during an event. Active information mining and sharing on a routine basis is valuable to identify the pertinent stakeholders and allow them to provide expertise during an emergency.