4

Use and Delivery of Health Care

The workshop’s second panel session included four speakers. Michael Paasche-Orlow, associate professor of medicine at the Boston University School of Medicine, opened the session by reviewing the progress that the health care delivery enterprise has made over the past decade at incorporating the concepts of health literacy into its interactions with patients. George Isham, senior advisor at HealthPartners, then discussed the link between health literacy and quality of care, and Russell Rothman, director of the Center for Health Services Research at Vanderbilt University, described ongoing efforts to create health-literate health care delivery. Victor Wu, managing director for clinical transformation at Evolent Health, provided some insights into the effects of the ACA on the health literacy field. An open discussion moderated by incoming roundtable chair Bernard Rosof, CEO of the Quality in Healthcare Advisory Group, followed the three presentations.

Before providing an overview of the progress that has been made over the past decade incorporating the concepts of health literacy into the use and delivery of health care, Paasche-Orlow noted the tremendous amount of social capital present at the workshop. He also noted the vast amount of

_______________________

1 This section is based on the presentation by Michael Paasche-Orlow, associate professor of medicine at the Boston University School of Medicine, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the IOM.

educational privilege in the room and the responsibility to use that privilege, as those present at the workshop have demonstrated that they are committed to working to create a system that cares about the most vulnerable populations.

In thinking about the topic of use, it is important to remember that there is no use without access, said Paasche-Orlow, and he pointed out that over the past decade, there has been improvement with regard to access in those states that have taken the necessary steps. He also remarked, though, that access will once again become a problem because of a limited capacity of the health care system to absorb more patients given the looming shortage of primary care physicians.

One of the lessons that comes from reviewing the literature that has evolved over the past decade, he said, is that when talking about access, use, and delivery of health care, it is important to use the lens of health literacy to do so. As the literature shows, health literacy is a significant mediator in the nexus between the relationship between individuals and systems, between the use side and the delivery side of health care. Health literacy is clearly an important core value for increasing equity, addressing disparities, promoting patient-centeredness, improving outcomes and quality, and reducing costs. “It is financially perilous to ignore the effects of health literacy,” said Paasche-Orlow.

Over the past decade, there has been a move from primarily observational work toward interventional work, though this evolution of the field is still in its early stages. There has also been a move from local exploration toward some examples of broader implementation, and he commented that the implementation of quality findings in health care in general is itself an emerging science that has developed over the past decade and is still developing. The incorporation of health literacy principles into training standards is also just beginning, and he added that, “you can build a workforce, but you also have to train providers to communicate effectively and this will require cultural transformation.” Paasche-Orlow said that the inclusion of core health literacy concepts such as universal precautions and teach-back that Howard Koh mentioned in his presentation are an important part of this cultural transformation, one that all clinicians are going to have to endorse and embrace and see as part of their mission.

Paasche-Orlow said there is still a great deal that this field needs to accomplish in the years ahead, and he listed three specific areas that need work. There is going to need to be a massive increase in education and support for patients, families, and social networks to understand and use health care effectively. Health care systems have to be activated and empowered to deliver a decent product while greatly reducing unnecessary complexity in every aspect of their interactions with patients, along the lines of the discussions in the previous panel about creating health-literate organizations.

Finally, while policy is starting to emerge that will advance health literacy and access in some areas, “policy that actually has teeth will have a bigger impact than just unfunded mandates. Figuring out where to put additional leverage points to promote health literacy behavior up and down the spectrum is going to be critical,” said Paasche-Orlow.

Closing on an optimistic note, he recounted the days when he would go to the heads of his hospital and talk about reducing readmission rates, they would tell him to leave, that their job was to keep hospital beds full. Today, this is no longer true; he credited policies with teeth for this cultural transformation. What he would like to see next are high-stakes testing policies that not only require new doctors to know how a kidney works but also to have to demonstrate the communication skills needed to confirm understanding. “In the end, that is going to end up moving the needle,” he said.

George Isham began his presentation by reiterating Koh’s remarks that it is important to move the conversation about health literacy from the clinical domain into the broader scope of health and public health. He then commented that there is some confusion about the definitions that those in the health literacy field use and about whether the field’s target is health care services or the outcome of health itself, which is affected by factors beyond health care services.

Several decades ago, said Isham, the IOM defined the quality of health services as the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge. To this definition, he would add interventions broader than health services and that the professions the definition refers to go beyond just doctors and nurses to include those professionals who interact with the community beyond health care delivery in ways that affect health more broadly. The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) quality toolbox website defines quality improvement as the systematic and continuous improvement in health services or health care services and the health status of targeted patient groups. Finally, there is the IOM definition of health literacy, which is the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.

In practice, health literacy is the place where skills and abilities meet the demands and complexity of health systems. There are opportunities on both sides of this equation, said Isham, and the field is now recogniz-

_______________________

2 This section is based on the presentation by George Isham, senior advisor at HealthPartners, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the IOM.

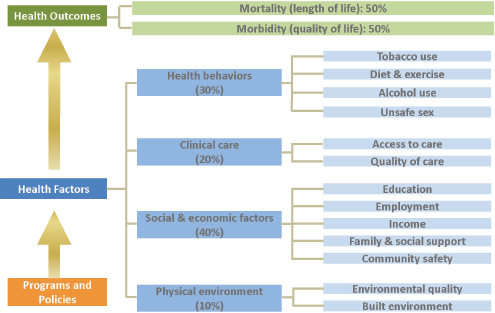

ing the impact of demands and complexity as a complement to addressing individual skills and abilities. In terms of how broad the definition of health services should be, he referred to data from the University of Wisconsin’s county health rankings and noted how much factors beyond clinical care impact health (see Figure 4-1). He recounted how even just a couple of decades ago, factors such as tobacco use, diet, and exercise were not even on the radar screen of health care delivery systems. Today, with the advent of the ACA and the increasing stress on community-wide efforts to improve health, the definition of health services needs to include other socioeconomic factors such as culture, education, and employment.

As an example, Isham remarked that his organization has an emphasis on children’s health that goes far beyond clinical care to include how to work with other agencies in the community around education and early childhood development. This broader focus, he explained, was stimulated by research findings as well as from thinking about the relationship between health and the physical environment.

Turning to the subject of health and quality improvement, Isham said it is important to have good focus when trying to improve quality, whether it is quality of health more broadly or quality of health care services. He

FIGURE 4-1 Many factors beyond those provided in the clinic impact health outcomes.

SOURCE: County Health Rankings, 2013.

noted that it is also important to consider that quality improvement work is about focusing on systems and processes and how they impact individuals. The basic framework for quality improvement work is to consider the available resources—people, infrastructure, materials, information, technology, and the like—what is done with those resources and how they are used, and what their impact will be in terms of the services delivered and on the satisfaction of patients, or more broadly that of individuals outside of the doctor’s influence (Donabedian, 1980).

Isham then referred to the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s model for improvement, which talks about aims, measures, tests of change, implementing change, and spreading change (Langley et al., 2009). He commented that there is still a long way to go in terms of developing measures of health literacy and how they are applied, and how the Plan, Study, Do, Act principle of testing and scale-up applies to any quality improvement effort. He then focused on the National Quality Strategy, a product of the ACA, and its three big areas of emphasis related to the triple aim of better care, affordable care, and healthy people and communities. Better care means improving the overall quality of care by making health care more patient-centered, reliable, accessible, and safe, while the focus on healthy people and communities aims to improve population health by supporting proven interventions to address behavioral, social, and environmental determinants of health, in addition to delivering higher quality care. The effort to provide affordable care aims to reduce the cost of quality health care for individuals, families, employers, and government.

One piece of the National Quality Strategy is the National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy, which includes the following goals:

- Develop and disseminate health and safety information that is accurate, accessible, and actionable.

- Promote changes in the health care system that improve health information, communication, informed decision making, and access to health services.

- Incorporate accurate, standards-based, and developmentally appropriate health and science information and curricula in child care and education through the university level.

- Support and expand local efforts to provide adult education, English-language instruction, and culturally and linguistically appropriate health information services in the community.

- Build partnerships, develop guidance, and change policies.

- Increase basic research and the development, implementation, and evaluation of practices and interventions to improve health literacy.

- Increase the dissemination and use of evidence-based health literacy practices and interventions.

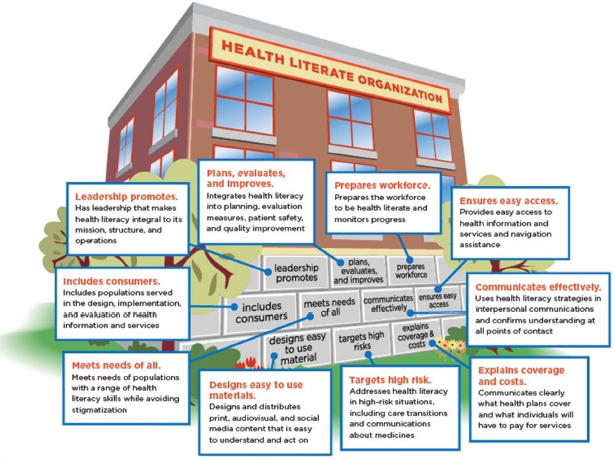

Brach and colleagues (2012) identified 10 attributes of a health-literate organization (see Figure 4-2). These attributes could be areas that the field could look at in terms of activities that influence health quality. “If we changed these features, it might result in a more health-literate result and better outcomes for our patients,” said Isham.

The basic strategy for improvement, said Isham, is the universal precaution strategy, which emphasizes structuring the delivery of care as if everyone may have limited health literacy. This strategy also recognizes that higher literacy skills in general do not necessarily equal better understanding, that health literacy is a state rather than a trait, and that everyone benefits from clear communication regardless of their health literacy status. AHRQ, Isham added, has developed the health literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit, which includes 20 tools, a quick start guide, a path to improvement, and more than 25 resources such as sample forms, PowerPoint presentations, and worksheets (DeWalt et al., 2010). “We have a number of elements for quality improvement as it relates to health literacy already in place,” said Isham, who noted that quality improvement in health care is a powerful tool in and of itself. He said that since it was introduced in the late 1980s by a number of large organizations, it has produced substantial improvements in health care that have impacted millions of people. Now, with the advent of the ACA and the development of ACOs, the infrastructure is being put into place to broaden that impact even more.

Isham then referred to an article by Koh and his colleagues (2012) that raises several important points. First, despite its importance, health literacy has until recently been relegated to the sidelines of health care improvement efforts aimed at increasing access, improving quality, and better managing costs. However, recent federal policy initiatives have brought health literacy to a tipping point. As a result, if public and private organizations make it a priority to become health literate, the nation’s health literacy can be advanced to the point at which it will play a major role in improving health care and health for all Americans. The key, said Isham, is indeed making health literacy a priority.

Isham concluded his presentation with some suggestions on how to move forward with quality improvement efforts that include health literacy. They included

- Link quality of care with improving broader health and health literacy. The concepts need improved clarity and definition.

- Systems need to make health literacy a priority.

- The issue would be more salient locally if the health literacy problem could be described contemporaneously and regularly in regional, state, and community populations.

FIGURE 4-2 Ten attributes of a health-literate organization.

SOURCE: IOM, 2012, p. 5.

- The established link between limited health literacy and poor outcomes needs repetitive communication and linkage to system’s emerging accountabilities and risk for population outcomes.

- The issue would be more visible on local health system agendas if they had the tools to personalize the issue to local enrolled, or patient, or ACO populations.

- The lack of valid, reliable, useful, and affordable practical public accountability and improvement health literacy performance measures are a relative barrier to action and accountability for that action.

- More examples of local action using evidence-based health literacy interventions to improve outcomes are needed.

- Accreditation programs for health organizations should include more items directly related to health literacy, such as the 10 attributes enumerated in a paper published by the IOM (Brach et al., 2012).

- Financial and non-financial incentives need to be developed and deployed to motivate action.

CREATING HEALTH-LITERATE HEALTH CARE DELIVERY3

The subject of Russell Rothman’s presentation was the 10 attributes of a health-literate organization that Isham mentioned in his presentation (see Figure 4-2) and a paper commissioned by the Roundtable that he and his colleagues at the Vanderbilt Center for Effective Health Communication authored (Kripalani et al., 2014). He noted the many studies to date in health literacy that have demonstrated that patients with lower health literacy can have poor knowledge and self-care, and even worse self-outcomes. The majority of these studies, he explained, focused only on individual health literacy or patient-provider communication and did not consider larger system-level challenges related to health literacy despite the paradigm shift that Koh referred to regarding the need to think about health literacy at the health system or organizational level. “When a patient interacts with a health care system, yes they are communicating directly with a provider, but there are many other facets of that organization that are at play and that impact the patient’s health,” said Rothman.

Patients, he explained, may interact with support services such as translators or patient navigators. They may be getting something in the mail to tell them about their appointment and they have to understand that

_______________________

3 This section is based on the presentation by Russell Rothman, director of the Center for Health Services Research at Vanderbilt University, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the IOM.

to know when to come to their appointment and how to get there. When they arrive at their appointment, they receive a clipboard of materials, such as HIPAA disclosures and permission to bill insurance companies, that they need to sign. Eventually, they see their provider, but they may also see nurses, dieticians, and other health care team members. Then they go home and may deal with billing statements and insurance benefits statements. “There really is a system level of activities going on that patients or families need to navigate that can impact their understanding of their health, their ability to perform self-care activities and have good health outcomes,” Rothman explained. The result, he added, is that the health literacy field needs to think about what is going on at the organizational level and whether or not an organization has policies in place, appropriate staff training, and understandable materials available for their patients so they can have the optimal experience that best benefits their health.

After recounting the definition of a health-literate organization as one that makes it easier for people to navigate, understand, and use information and services to take care of their health (Brach et al., 2012), Rothman listed the following 10 attributes of a health-literate organization:

- Has leadership that makes health literacy integral to its mission, structure, and operations;

- Integrates health literacy into planning, evaluation measures, patient safety, and quality improvement;

- Prepares the workforce to be health-literate and monitors progress;

- Includes populations served in the design, implementation, and evaluation of health information and services;

- Meets the needs of populations with a range of health literacy skills while avoiding stigmatization;

- Uses health literacy strategies in interpersonal communications and confirms understanding at all points of contact;

- Provides easy access to health information and services and navigation assistance;

- Designs and distributes print, audiovisual, and social media content that is easy to understand and follow;

- Addresses health literacy in high risk situations, including care transitions and communications about medicines; and

- Communicates clearly what health plans cover and what individuals will have to pay for services.

The aim of the work that the Roundtable commissioned was to identify and evaluate current measures for assessing organizational health literacy, and to try to reach out to health care organizations to understand how they are measuring and addressing organizational health literacy. Toward that

end, Rothman and his colleagues performed a systematic review to identify measures of organizational health literacy. The first conducted a MEDLINE search for abstracts and articles in which researchers were trying to measure organizational health literacy. This search included all English-language articles from January 2004 to February 2014 and focused on measures of health literacy at the organizational level, excluding those papers and abstracts that looked at measures of individual health literacy and review articles. Recognizing that this is a young field, the Vanderbilt team also searched the so-called gray literature using Google search and by reaching out to experts in the field using listservs and a snowball sampling process to try to identify additional measures that organizations might be using.

Once Rothman and his colleagues identified potential measures, one member of the team reviewed all of the abstracts and papers to identify eligible measures, which were then reviewed by two team members to see how well these measures addressed the 10 attributes of organizational health literacy and to see what kind of work had been done to validate the measure that was developed. Reviewers also looked at whether the measure was being used and how it was being used by organizations. A third member of the team was brought in when needed to reach consensus, said Rothman. The team also used snowball sampling to try to understand how organizations would use these measures in the real world.

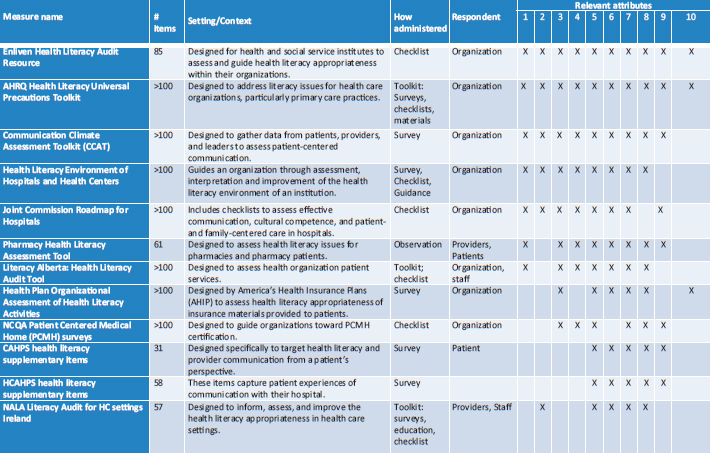

The team reviewed 1,926 articles and 59 other sources of information that the team received through the snowball sampling and gray literature. From that initial pool, the team identified 68 measures that were addressing organizational health literacy in some capacity. They considered 12 of the measures as very comprehensive, addressing 5 or more of the 10 attributes (see Figure 4-3), with 2 of them addressing all 10 attributes. Another 27 measures addressed between 2 and 4 of the attributes and 29 more measures focused on just one attribute, usually interpersonal communication. Rothman pointed out that only 3 of the measures addressed attribute 10, which has to do with how patients understand cost or billing information related to their health, an issue that is becoming more important as patients are being asked to pay for a greater share of their health care. He commented, too, that there is a growing demand for transparency in cost, yet the billing forms that a patient receives are often far from understandable. “There are huge opportunities to look at what organizations are doing around explaining cost issues,” he said.

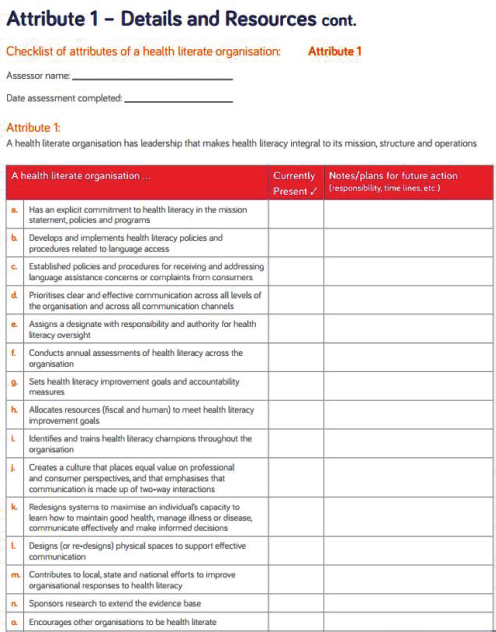

The Enliven tool, one of the more robust measures the team identified, addresses all 10 of the attributes. Consisting of 85 items, it is basically a checklist to ask an organization if it is addressing the 10 attributes. It is designed to be completed by an organization, Rothman explained. For example, a checklist of 15 items is used to measure attribute one—whether

FIGURE 4-3 Measures with five or more attributes of a health-literate organization.

SOURCE: Kripalani et al., 2014.

the organization has leadership that makes health literacy integral to its mission, structure, and operations (see Figure 4-4).

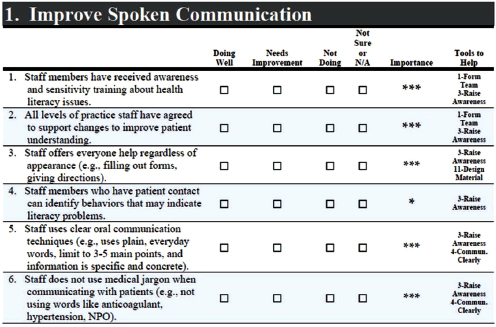

Another robust tool measuring all 10 attributes is the AHRQ Universal Toolkit. This 227-page compendium of more than 20 tools and measures is designed to be completed by staff and the organization. Within the toolkit is a 49-item health literacy assessment questionnaire that covers whether an organization is addressing spoken communication (see Figure 4-5), written communication, self-management, and empowerment in support of systems.

The Communication Climate Assessment Toolkit, developed by a team at the American Medical Association, measures all but the 10th attribute and is referred to as a 360-degree measure because it has different forms for different participants. The forms can be completed by organizational leaders, physicians and other providers, and patients. The toolkit is available in 11 languages and can be administered in person, online, or via phone. Rothman noted that the team that developed this toolkit has done some research demonstrating that it has some good construct validity with positive correlations between performance on the tool or the measurement scale and patient-reported quality of care and trust in the health care system. The researchers also demonstrated that the toolkit has good internal reliability.

The Health Literacy Environment of Hospital and Health Centers Toolkit, developed by Rima Rudd and her colleagues, has been field tested in hospitals, clinics, and other health care organizations in the United States, as well as in Australia, Europe, and New Zealand. This toolkit includes assessments for navigation, print communication, oral exchange, availability of patient facing technologies, policies and protocols, the use of plain language, and other measures of health literacy.

Rothman said that the 12 robust measures for addressing organizational health literacy are more than he expected to find when he and his colleagues started this project. “Several of the measures were developed specifically to address organizational health literacy, but others were originally developed to try to address how patient-centered an organization was or whether or not an organization was meeting criteria for patient-centered medical home. In that process, they were also addressing a lot of the attributes related to organizational health literacy,” said Rothman. He added that most of the measures they identified have good content validity, meaning that they seem to be measuring the right things, but that there has been limited work to date to truly assess the construct validity or reliability of these tools. “There has not been a lot of robust work to see if they have utility in predicting health outcomes over time,” Rothman added.

The second aim of this project was to determine how organizations are using these measures and specifically if they were using them for reporting, accountability, management, quality improvement, and research. He said

FIGURE 4-4 The Enliven tool’s checklist measuring whether an organization is meeting the definition of attribute one.

SOURCE: Thomacos and Zazryn, 2013.

FIGURE 4-5 One component of a health literacy assessment in the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Universal Toolkit.

SOURCE: AHRQ, 2010.

that at this point, not much has been published about how organizations are using them, but he added that he believes these measures can be used for reporting, accountability, management, quality improvement, and research. “Actually, we would really encourage that. We think there are fantastic opportunities for organizations to use the measures that are out there to apply it to their system to improve how they assess health literacy in all of these different areas,” said Rothman.

Some of these measures have been widely distributed. The Joint Commission Roadmap for Hospitals, for example, has been downloaded more than 40,000 times, and the Health Literacy Environment of Hospitals and Health Centers, as he had mentioned, has been used both nationally and internationally. The Communication Climate Assessment Tool has been accessed widely and the Health Plan Organizational Assessment of Health Literacy, which was developed by American Health Insurance Plans, has also been distributed nationally. This assessment tool was developed by a health literacy task force drawn from the organization’s 65 member plans to look at how health plans address health literacy. The organization has been able to push this tool out to their health plans and encourage its use as a way to assess how they are addressing health literacy and try to drive improvement in this space.

From their snowball sampling, the Vanderbilt team concluded that many health care systems are trying to address organizational health literacy in some way, but that they are early on in the process. They may have gotten a tool or a few tools or they may have pulled together some questions from several different tools, explained Rothman. Most of these organizations are starting to assess health literacy, but they may not yet have taken action to address health literacy or validate the tools they are using. Many groups are, however, starting to hire staff in the patient education, patient engagement, or patient experience sections of their health systems to start addressing organization health literacy, which he characterized as very encouraging.

Sutter Healthcare in California is just one example of an organization that mixed and matched measures, taking some materials from the AHRQ Universal Precautions Toolkit and adapting other materials from the IOM paper on the 10 attributes as well as some measures from the Consumer Assessment of Health Providers and Systems (CAHPS) health literacy supplementary items. Sutter Healthcare is now using this amalgam to try to measure how it is addressing organizational health literacy to help drive organizational change. Other examples include Novant Health and Carolinas HealthCare System, both of which are using the AHRQ Universal Precautions Toolkit and the CAHPS measures to try to assess health literacy at their organizations and make changes in their organizations to address it.

In conclusion, Rothman said that he and his colleagues found a robust array of measures that are now available that could be used or adapted for use by organizations. While many of these measures are meant to be completed by the organizations, he said his personal belief is that the measures that try to address organizational health literacy from all perspectives—the organization’s, the provider’s, and the patient’s perspective—are going to be the most useful and the most robust measures. He also said that these measures can and should be used today for measurement, for accountability, and for quality improvement even though the current data on the validity and reliability of these tools is still somewhat limited.

Rothman also commented on the limitations of this study, noting that the team relied on identification of measures that were published or referred to them and on those written in English. He acknowledged, too, that it can be difficult to assign the individual measurement items to the specific attributes. He also cautioned against picking measures from different instruments or toolkits because that reduces validity. The ideal situation, he said, would be to have a unified adopted measure that was used by many different organizations at the same time and over time to look at what the variation is and how organizations are addressing health literacy, both in the United States and internationally. This ideal situation would also allow

the tool to be validated in terms of how well it predicted health outcomes over time.

“I do feel we are at a crossroads here,” said Rothman, “given the opportunities created by the Affordable Care Act’s focus on population health, the wave of individuals getting insurance coverage for the first time, and the large and growing number of organizations and groups that understand the importance of patient-centered care and patient-centeredness.” As a result, he added, there is a tremendous opportunity to push organizations to measure and address organizational health literacy, and he hoped the Roundtable can continue to lead that effort.

HEALTH LITERACY AND THE AFFORDABLE CARE ACT4

In this session’s final presentation, Victor Wu focused on the impact of the ACA on vulnerable populations, particularly with regard to how the concept of health literacy is being brought to bear to address the demands and complexities of health insurance enrollment. The ACA, he noted, has transformed access to health insurance, which comes as no surprise given all of the attention devoted to trying to enroll individuals who had previously been locked out of the health insurance marketplace. As a result, the number of Americans without health insurance is now at a historic low (Sommers et al., 2014). Some 8.5 million new individuals accessed and purchased health insurance through federal and state insurance exchanges, and there are another 5 million or so enrollees in Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program.

Wu explained that vulnerable populations are overrepresented among the newly enrolled, just as they were disproportionately represented in the uninsured population. After the first open enrollment period, two out of three of the newly insured who enrolled through the marketplaces reported that they had difficulty understanding terms such as provider network, deductible, and premium. He added that of those who bought insurance through the marketplaces, 6 of 10 were previously uninsured and 8 of 10 were eligible for tax credits.

To better understand the challenges facing these individuals, Wu and colleagues Ruth Parker and Kavita Patel interviewed organizations across the country at the local, state, and national levels who have had direct contact with new enrollees through assisters, navigators, certified application counselors, and others who work on the frontlines with those applying for health insurance for the first time. In particular, he and his collaborators have focused on identifying success strategies for hard-to-

_______________________

4 This section is based on the presentation by Victor Wu, Evolent Health, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the IOM.

reach or vulnerable populations as defined by the organizations themselves. These populations included, but were not limited to, those with limited English proficiency; African Americans, Hispanics, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders; immigrants; lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) populations and homeless and run-away youth; and low-income populations.

Before discussing the strategies these organizations used to reach these vulnerable populations, Wu provided some anecdotal examples. For example, the best assisters for the LGBTQ community were, perhaps not surprisingly, individuals who identified as LGBTQ. Similarly, in some groups the head female in the household was the health decision maker, but that was not the case in the Asian American and Pacific Islander community. These organizations reported that there was no substitute for an in-person encounter with someone who spoke the potential enrollee’s language. Some organizations also reported that having data about the communities they were trying to reach was key, and others noted that even after successfully signing up individuals and families for insurance they were contacted several times with questions on how to use it. Several organizations reported that their communities needed multiple “touches” before being ready to sign up for insurance.

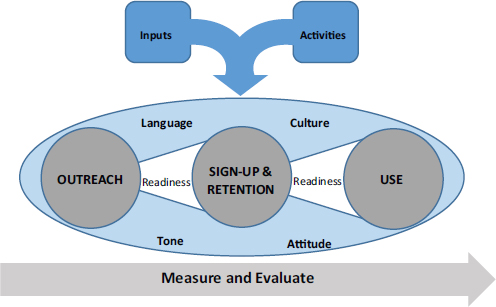

Based on these interviews, Wu said that a new framework for thinking about health insurance enrollment is in order. Rather than dividing the process into two components of outreach and enrollment, there should be three components: outreach and education, sign-up, and then use. These three are interconnected and integrated in many ways, Wu explained (see Figure 4-6). The consumer needs to become comfortable with one component before moving to the next. Thinking about the enrollment process as an integrated system means that those who work in outreach need to think about how to get people ready for the next step, sign up, and similarly, those who help people actually fill out the enrollment forms need to get their clients ready to ask questions about how to use their new insurance, find a provider in their network, and use health services that will improve their health.

Underlying all three of these bins, Wu continued, are issues related to language and culture, and to the tone and attitude of those people in the health insurance system and health system with whom these new enrollees interact. These four underlying inputs drive the ways in which people navigate and go through what is broadly called health insurance enrollment. In addition, there are what Wu called inputs and activities, the organizations and people that interact with the uninsured and the plan of attack that they use to reach those individuals and bring them into the system. Finally, said Wu, a framework for health insurance enrollment should also include measurement and evaluation that provides helpful, meaningful, and actionable information to improve the entire enrollment process.

FIGURE 4-6 A model for engaging consumers in getting and using health insurance.

SOURCE: Parker et al., 2015.

One of the high-level strategies that came from the interviews is that three major components in this framework should be integrated into a mutually supportive, iterative process, Wu said. Oftentimes, individuals go back and forth between these bins at different points in the enrollment process until they reach a level of understanding that is meaningful and empowering. One of the strategies that organizations have taken in response to this type of learning behavior is to create opportunities for multiple touch points during the enrollment process, and to go along with that, they establish multiple convenient and consistent times and locations at which individuals can get help. Wu noted that it may take at least four interactions before an individual will sign up and think about using their health insurance, which makes it important for individuals to know where and when in their community they can interact with the enrollment process.

Wu said that another important lesson is that in-person assistance is essential for vulnerable populations. As Wu and colleagues learned from the interviews, those working in the field consider in-person assistance as the gold standard for helping individuals in vulnerable populations navigate through the three components of the enrollment process. Organizations also reported a need for a standardized process for information exchange among local partners and between state and federal officials to share best practices and to collaborate on solving problems that occur on the frontlines of the enrollment process.

The second high-level strategy that successful organizations use is to equip the assisters with information, training, and materials that will enable them to engage in conversations about the value of health insurance, the options available, how to use it, and what it will cost. Assisters need to be prepared to have difficult conversations with anyone who is looking for insurance access for the first time, but in particular those in vulnerable populations. “Comprehensive conversations regarding the cost and affordability of health insurance must be constructed and incorporated to help ensure successful signup and retention,” said Wu, who explained that in practice this means equipping the navigators and assisters with the right material for the right consumer at the right encounter.

Diagnosing and filling knowledge gaps to help better approach and meet consumers where they are in terms of their level of understanding is, Wu said, essential. As an example, Wu said that many immigrants come from countries where there may be universal care or where there is no health insurance system at all. “Forget talking about how to use it, forget talking about premiums, and forget talking about deductibles. They are not even familiar with the concept of health insurance,” said Wu. Along those lines, it can help to prepare understandable analogies and anecdotes that assisters can use to help explain complex concepts. Cost, for example, is an incredibly complicated and sensitive subject, and organizations that were successful in having conversations about cost found that anecdotes and analogies to which individuals could relate were vital to the process.

The third strategy identified during the interviews was to meet individuals where they live. “We learned that identifying data describing uninsured populations, preferably by zip code, and making those data available to assisters was one of the best strategies to find and target those individuals,” said Wu. These geo-coded data also helped frontline workers have the right materials and information available for specific populations. One organization in Florida, for example, found that such data allowed it to target specific groups with materials that reflected culture, ethnicity, language, age, gender, literacy levels, and income.

The fourth strategy involves building trust and to do that by intentionally designing processes that will build trust with targeted populations and provide actionable steps for consumers. It was vital, Wu explained, to identify and use trusted community sources and “unofficial” trusted advisors in outreach efforts. One lesson learned from those working with immigrant populations is that individuals who spoke English well and had connections in the communities were viewed as trusted sources. Using them as extensions into the community and spreading information that was accurate were important factors in boosting enrollment in those communities. For many vulnerable populations, it was also important to choose physical locations that are neutral or trusted sites that help reduce the stigma associated

with some terms being used to describe who was eligible for insurance for the first time under the ACA.

The final strategy is to create health-literate materials, which Wu said goes without saying, but is incredibly difficult to do in practice. He noted that while many tools are available for achieving this, there is a need to facilitate the development of culturally sensitive, accurately translated, and actionable health-literate materials for vulnerable populations. For example, there are so many translated documents available for Spanish-speaking individuals that they become confusing because they use different definitions for premiums and deductibles. Having action-oriented materials and checklists was also instrumental for helping people move through the stages of enrollment.

Concluding his presentation, Wu said the projections for 2015 estimate there will be 5 million new enrollees. “We are positive they are going to be even harder to reach,” said Wu, noting that the projections suggest these individuals will have an even lower level of education, be concentrated within Spanish-speaking communities, and be geographically concentrated in the southern United States. Wu concluded by saying that, in addition to the outreach efforts that will be needed to reach these populations, it will also be important to retain those who were new enrollees in 2014 and to now provide those individuals with the health-literate materials and information they need to make the best use of their new insurance to benefit their health.

Session moderator Bernard Rosof started the discussion by agreeing with Isham that the National Quality Strategy, which encompasses the triple aim of providing better care, improving health care of the community and the population, and making care affordable, depends heavily on health literacy. He also agreed with Rothman that the measures his team identified will be helpful for driving the transformation of systems into health-literate systems, and he wondered if there are metrics to demonstrate whether organizations are improving in that regard and if they are identifying gaps where they can improve. He also wondered if that was something the Roundtable could discuss and catalyze. Rothman replied that the Roundtable should encourage and move forward with pushing for organizations to measure organizational health literacy and to do so in a way that helps organizations make these measurements in a robust way that optimizes the opportunity for evaluation. It would also be important to try to get multiple sites using the same metrics in order to have more power to look at the predictive utility of measuring and addressing health literacy.

Rothman also commented that one of the challenges in doing quality

improvement is to not just rush in and start measuring things without a robust evaluation plan in mind, and that perhaps the Roundtable could help organizations think through what they should be measuring at baseline so they can conduct their quality improvement assessments with an improvement plan in mind. Ideally, he added, these measures will be linked to improved patient satisfaction, patient self-care behaviors, and patient health. “Ultimately, we need to make the link that addressing organizational health literacy does ultimately lead to improved patient health outcomes,” said Rothman.

Isham remarked that the Vanderbilt group’s work and the resulting paper has been helpful in describing where the field is with respect to measurement, and he agreed with Rothman that until there are organizations using a subset of these measures in a way that is consistent and that they can share with one another, the field will not quite be at the point to have broad-scale assessment of organizational health literacy. He noted, though, that many of the tools identified are labor-intensive to deploy within an organization, particularly if they are used repetitively to assess improvement efforts, and that work remains to enable organizations to deploy these measurement tools in a manner that will meet the needs of each specific organization. Reflecting this state of affairs is the fact that there are no measures that are ready for submission to the National Quality Forum or other regulatory or accountability organizations for broad use. “That doesn’t mean we should be discouraged, just that we have a long way to go,” said Isham.

The other point he raised was that the field needs to be aware that health literacy is an issue in different ways for different populations and different geographies. Although national survey data show how prevalent low health literacy is in the nation and how that is related to outcomes, those data need to be duplicated at local and organizational levels in order to get the attention of those who need to focus on health literacy where it intersects with real people. “Those components of measurement are critical to getting organizations to devote resources and actually improve the situation,” said Isham. Paasche-Orlow added that these measurements will eventually have to be made at the individual level as well to really determine if these interventions are having an effect on the disparities that need addressing.

Catina O’Leary, president and chief executive officer of Health Literacy Missouri, asked Rothman for his thoughts about possible internal biases from asking people to evaluate themselves on measures that are sensitive and complicated. Rothman agreed with her concern about bias and said it is an important challenge with some of the organizational health literacy assessment tools that are available, which is why he believes that the tools that measure from multiple perspectives are likely to be more robust.

He acknowledged that there is subjectivity in many of the measures and that there has not been enough work done assessing the validity of those measures. Even when the measures try to be more objective there can be subjectivity, he said. For this example, the question “What percentage of your staff has received health literacy training?” may seem objective, but without a definition for what training is, one organization might consider 20 minutes of training as enough, while another would only consider staff trained with regular classes. Paasche-Orlow added that it is time to engage with an accrediting organization that can serve as outside eyes.

Rima Rudd, senior lecturer on health literacy, education, and policy at the Harvard School of Public Health, noted that many of her colleagues in Europe are moving from patients to consumers to communities in their deployment of measures of health literacy, and perhaps that is something the U.S. research community should consider. Isham remarked that the universal precaution strategy is one way, albeit a blunt one, to address that challenge, but that it can be used to tailor an approach to individuals based on health literacy skills. He also noted that information technologies will be a big help with moving from the individual to the community.

Rudd then brought up what she called the elephant in the room—the lack of assessments for health professionals. While there are fairly robust measures of patient skills or deficits and the link between those and outcomes, there is a need for measures of the communication skills of health professionals and their link to outcomes. “I would venture a guess that we cannot easily move ahead with assessments of institutions until we have those measures and the assessments of the professionals working within the institutions,” said Rudd. Isham, Paasche-Orlow, and Rosof all agreed that this was an important point. Rothman said there has been some focus on the communication skills of the physician or key provider in the room, but little if anything has been done with the other members of the health team with whom the patient may interact. “We don’t look at it from a full system level. We tend to get down to the one patient, one provider level,” said Rothman.

Following up on the point about assessing the entire health care team, Betsy Humphreys said that it is more important to look at the team as a whole rather than ensuring that every member of the team has to be a great communicator.

Parker asked the panelists who they thought might be good partners for attribute 10, the issue of having transparency around cost or what might be considered as making the business case. Rothman said that the most obvious partner is government given that state and federal governments are major payers for health care. In particular, he said, Medicare has started to get involved in making cost transparent, but there is a huge need to improve the clarity of the message around some of these cost issues. He noted that

there are private organizations that are moving into the cost space, including one company that he knows of that was founded around transparency of cost for laboratory tests for individuals.

HealthPartners, said Isham, “has been very active in terms of promoting measures of cost of care,” and has developed a measure for total cost of care.5 The reason why there are not many measures available goes beyond the area of health literacy, and there is resistance from a number of sources about making costs transparent. The attitude of many in health care is that the preferred state is one in which there is the freedom to deliver quality care regardless of cost. Because of political pressure, Isham added, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute is prohibited from looking at cost in its comparative effectiveness research. Some private organizations, such as the National Committee for Quality Assurance and the National Quality Forum, are starting to look at cost transparency and cost measures. There is an emerging appreciation for cost of services, not just performance, thanks to the ACA, Isham added. Rosof said his firm has been active in this space for some time and his opinion is that a public–private partnership would be an obvious approach to take. To the two organizations that Isham listed, he suggested The Brookings Institute or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation as potential partners in such an effort.

Michael Villaire, CEO of the Institute for Healthcare Advancement, reiterated Wu’s point that retention is just as important as enrollment. He added that his organization has developed some best practices that address retention. He also commented that there is an interesting aspect to the issue of informing people how to use their new health insurance, and that has to do with the behaviors that the chronically uninsured have developed and that may be barriers to getting the care they needed. These barriers may include failure to obtain preventive care, lack of a primary care physician, or use of the emergency room for routine care. By understanding these behaviors, it may make it easier to change those behaviors so that these individuals get better care now that they have insurance.

_______________________

5 See http://www.healthpartners.com/tcoc (accessed May 11, 2015).

This page intentionally left blank.