1

The National Flood Insurance Program and the Need for Accurate Rates

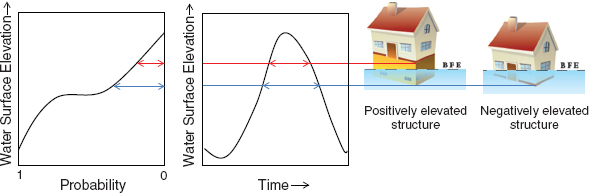

Floods take a heavy toll on society, costing lives, damaging homes and property, and disrupting businesses and livelihoods (e.g., Figure 1.1). Of all natural disasters, floods are the most costly (Miller et al., 2008) and affect the most people (Stromberg, 2007). Since 1953, nearly two-thirds of presidential disaster declarations—which trigger the release of federal funds for community recovery and relief—have been flood related. Moreover, the number of flood disaster declarations has increased over the past 60 years, from an average of about 8 per year in the 1950s to a record high of 51 in 2008 and 2010 (Figure 1.2). Flood losses are increasing because more people are living in harm’s way; more expensive homes are being built in the floodplain (Michel-Kerjan, 2010); and development in watersheds and climate changes, such as sea level rise and more frequent heavy rainstorms (IPCC, 2012; Melillo et al., 2014), are increasing flood risk (the likelihood and consequence of flooding) in some areas.

The National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) was created in 1968 to reduce the flood risk to individuals and their reliance on federal post-disaster aid. The program enabled residents and businesses to purchase federal flood insurance if their community adopted floodplain management ordinances and minimum standards for new construction in floodprone areas. Insurance rates for new structures were intended to reflect the risk of flooding (i.e., risk-based rates), with rates depending on structure elevation and other factors. Rates for existing structures were subsidized to keep property values from dropping immediately and to encourage communities to participate in the NFIP and manage development in the floodplain. Within NFIP participating communities, flood insurance is mandatory for homes and businesses with a federally backed or regulated mortgage in high flood risk areas (called Special Flood Hazard Areas), and is available for homes and businesses in moderate to low flood risk areas.

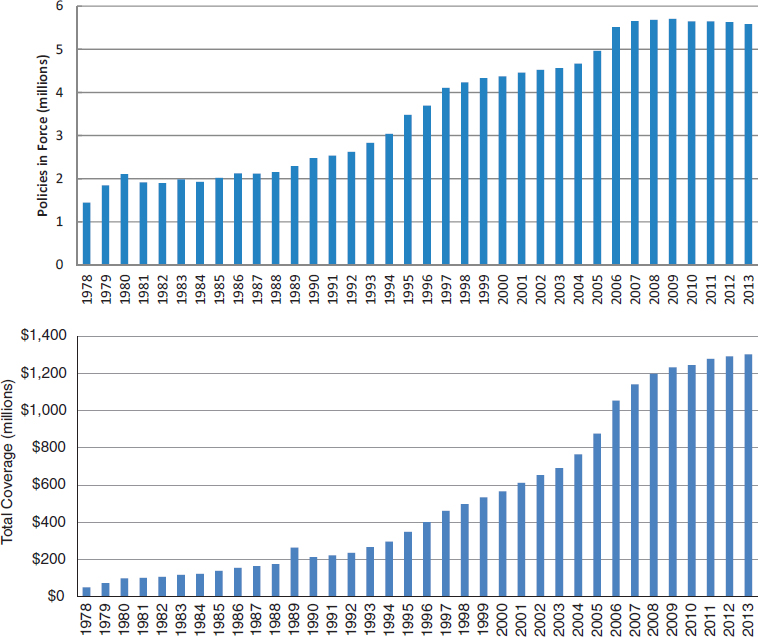

Today, about 20 percent of the NFIP’s 5.5 million policies receive subsidized flood insurance rates. Subsidized structures are located across the nation, with the largest concentrations along the coasts (NRC, 2015). Rates for subsidized structures do not depend on elevation (although elevation affects risk), and so only a few of these structures have been surveyed to determine their elevation. However, most subsidized structures are thought to be negatively elevated (see Figure 7.2 in PWC, 1999),1 that is, to have lowest floor elevations lower than the base flood elevation. This is the water surface elevation with 1 percent annual chance of being exceeded, and it is the NFIP benchmark for construction standards and floodplain management ordinances. Structures with lowest floor elevations equal to the base flood elevation have a 26 percent chance of flooding during the lifetime of a 30-year mortgage (compared with a 1–2 percent chance of catching fire; FEMA, 1998). Negatively elevated structures have a much higher chance of flooding over the same period and a greater potential for damage.

______________

1 Personal communication from Andy Neal, Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), on July 9, 2014. The NFIP has elevation data for only 2.2 million policies, most of which are charged actuarial rates.

FIGURE 1.1 Flooding of homes and businesses in Minot, North Dakota, in July 2011, when the Souris River (also known as the Mouse River) overflowed its banks. SOURCE: Photo by Patsy Lynch, Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Available at http://www.fema.gov/media-library/assets/images/59875.

FIGURE 1.2 Number of presidential disaster declarations (black line) and declarations associated with flood-related events (blue line) from 1953 to 2013. SOURCE: Data from FEMA, http://www.fema.gov/disasters/grid/year.

FIGURE 1.3 The flood risk to a structure depends in part on the elevation of the lowest floor of a structure (red and blue horizontal lines) relative to the base flood elevation (BFE). (Left) A typical water surface elevation–probability function. Compared to structures built above the base flood elevation, negatively elevated structures have a greater probability of inundation with shallower depths, and they are inundated to greater depths by lower probability events. (Center) A typical flood hydrograph for riverine flooding. Because negatively elevated structures are lower in the floodplain, a given flood will commonly inundate them for a longer period of time than structures above the base flood elevation.

With the passage of the Biggert-Waters Flood Insurance Reform Act of 20122 and subsequent legislation, subsidies are beginning to be phased out and premiums are expected to rise to levels that reflect the full risk of flooding (see “National Flood Insurance Program” below). Premium increases for those negatively elevated structures are likely to be substantial, given the high flood risk and loss of the large subsidy. The NFIP’s current method for calculating risk-based rates was developed for structures built at or above the base flood elevation, but negatively elevated structures are susceptible to different flood conditions (e.g., more frequent flooding) and drivers of loss and damage (e.g., deeper and longer duration of flooding; Figure 1.3). Adjustments to account for these conditions in the rate setting method may be necessary to ensure that rates for negatively elevated structures are credible and fair.

This report evaluates methods for calculating risk-based premiums for negatively elevated structures and examines data and analysis needed to support risk-based premiums for these structures, as well as issues of feasibility, implementation, and cost of underwriting risk-based premiums for negatively elevated structures (Box 1.1). As specified in the charge, the focus is on the methods for calculating premiums, not on what those premiums should be. A separate report (NRC, 2015) addresses the affordability of NFIP insurance premiums. At the request of the NFIP, the analysis focused on single family homes, which make up the majority of NFIP policies.

NATIONAL FLOOD INSURANCE PROGRAM

Insurance provides a means for an individual or business to transfer the risk of potential losses to another entity in exchange for payment of a premium. In the early part of the 20th century, private flood insurance was offered in some areas, but was not widely available because of inadequate information for projecting the cost of future flood losses, the potential for catastrophic losses for insurers, and the expectation that only those at high risk of flooding would seek insurance, thus diminishing the ability to spread risk (Pasterick, 1988). State regulation of insurance prices and tax policies limiting the ability to build adequate reserves added further disincentives for private companies to offer flood insurance. Private insurance companies stopped covering flood losses in 1929, a few years after a Mississippi River flood inundated 13 million acres of land and left more than 700,000 people homeless (AIR, 2005).

_______________________

2 Public Law 112-141.

BOX 1.1

Study Charge

An ad hoc committee will conduct a study of pricing negatively elevated structures in the National Flood Insurance Program. Specifically, the committee will

- Review current NFIP methods for calculating risk-based premiums for negatively elevated structures, including risk analysis, flood maps, and engineering data.

- Evaluate alternative approaches for calculating “full risk-based premiums” for negatively elevated structures, considering current actuarial principles and standards.

- Discuss engineering, hydrologic, and property assessment data and analytical needs associated with fully implementing full risk-based premiums for negatively elevated structures.

- Discuss approaches for keeping these engineering, hydrologic, or property assessment data updated to maintain full risk-based rates for negatively elevated structures.

- Discuss feasibility, implementation, and cost of underwriting risk-based premiums for negatively elevated structures, including a comparison of factors used to set risk-based premiums.

After devastating flooding from Hurricane Betsy triggered losses of more than $11 billion (in 2014 dollars; Michel-Kerjan, 2010) in 1965, the federal government began studying the feasibility of offering flood insurance (AIR, 2005). A few years later, Congress passed the National Flood Insurance Act of 1968,3 which established the National Flood Insurance Program. The program set minimum standards for development in the floodplain (i.e., elevating structures to at least the base flood elevation, limiting development in designated floodways) and offered federal flood insurance to residents and businesses in communities that agreed to adopt and enforce ordinances that meet or exceed NFIP standards. Under the program, federally funded engineering studies and modeling would be used to assess and map flood hazards. This information would be used to promote better land use and construction decisions, and thereby reduce future flood losses as the vulnerability to inundation diminished over time. It would also be used to support insurance rate setting. The Federal Emergency Management Agency currently administers the NFIP, sets insurance rates commensurate with program guidelines, and carries out floodplain mapping and analysis to support rate setting and floodplain management.

The NFIP was modeled after personal lines of insurance (e.g., homeowners, automobile), with risks grouped into classes and limited use of individual risk ratings. However, NFIP insurance differed from private insurance in three key ways. First, the NFIP was not initially capitalized. Rather than hold sufficient funds for eventual heavy flood losses, the program would receive an infusion of funds from the federal treasury when necessary. Limited borrowing authority from the federal treasury would provide a short-term backstop to enable insured claims to be paid in cases of high losses. Second, the NFIP could not choose who would be insured. All residents and businesses in a participating community would have access to NFIP flood insurance, even the high risk policyholders. Third, owners of existing homes and businesses (the majority of policyholders) were charged premiums that were significantly lower than warranted by their risk of flooding. It was anticipated that over time, older floodprone construction would be removed from the policyholder base, and the new policyholders would pay risk-based rates. No provision was made to cover the premium shortfall, such as routinely infusing funds into the program or building additional charges into premiums for newer construction.

Over the years, Congress made a number of adjustments to the NFIP. A changing mix of incentives and penalties, coupled with periodic reminders of the adverse consequences of flooding, led to significant growth of the program. The number of policies issued rose from about 1.5 million in 1978 to 5.5 million at

______________

3 Public Law 90-448.

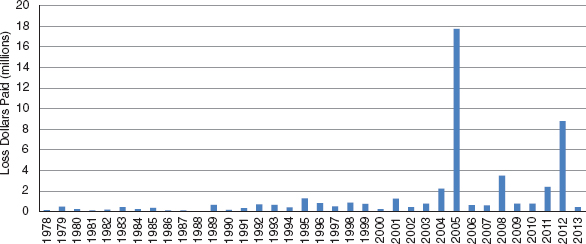

FIGURE 1.4 NFIP statistics by calendar year. (Top) Total number of policies in force. (Bottom) Total coverage of NFIP policies in millions, not adjusted to a common year. In 2012 dollars, coverage rose from $178 billion in 1978 to $1.3 trillion in 2013. SOURCE: FEMA, http://www.fema.gov/statistics-calendar-year.

the end of 2013 (Figure 1.4, top). In addition, the total value of property insured by the NFIP rose from $178 billion in 1978 (in 2012 prices) to $1.3 trillion in 2013 (Figure 1.4, bottom). The increase in insured value has been attributed to two factors: (1) policyholders purchase nearly twice as much flood insurance as they did 30 years ago4 and (2) the population and number of policyholders has increased substantially in coastal states, which now account for a large portion of the NFIP portfolio (Michel-Kerjan, 2010). Some important changes to the NFIP over its history are summarized below.

________________

4 Homeowners can obtain coverage up to $250,000 for structures and $100,000 for contents. Inflation-corrected data show that the average quantity of insurance per policy almost doubled over 30 years, from $114,000 in 1978 to $217,000 in 2009 (Michel-Kerjan, 2010).

Evolution of the NFIP

The NFIP began operations in 1969, and a consortium of private companies (the National Flood Insurers Association) was established to sell and service NFIP flood insurance policies (AIR, 2005). At the time, the purchase of flood insurance was not required. In 1972, Hurricane Agnes revealed that few property owners had availed themselves of NFIP flood insurance. The Flood Disaster Protection Act of 19735 made insurance purchase mandatory for any resident with a federally backed mortgage in an NFIP-participating community. Lenders were responsible for ensuring that this requirement was carried out. To encourage acceptance of the new insurance purchase requirements, insurance subsidies were expanded to cover structures built after initial floodplain mapping, but before 1975, and the subsidized rates were substantially lowered. As a result, community and state participation in the NFIP greatly expanded and the number of policies increased.

Other public policy decisions made in the 1970s concerned changing flood risks. Development in the floodplain and other factors (e.g., climate change) might increase the flood risk for some structures that had been built in compliance with NFIP standards. To prevent large increases in premiums, these structures were allowed to retain their lower risk rating classification if conditions beyond the control of the property owner later increased the flood risk. This practice is often referred to as administrative grandfathering. It was anticipated that the rates for classes with grandfathered properties would have to be adjusted over time to reflect the mix of some higher risk properties.

In the 1970s, most of the properties in the NFIP were older construction and received subsidized insurance rates. Consequently, the premiums collected were insufficient to cover the annual costs of the program. From 1981 to 1988, rates were increased and coverage was changed to reduce premium subsidies and to improve the financial condition of the NFIP. Another major change concerned private insurance company participation in the NFIP. In 1977, the National Flood Insurers Association dissolved its relationship with the NFIP because of disagreements about authority, financial control, and other operational matters (AIR, 2005). In 1983, the Write Your Own Program reestablished a relationship with insurance companies, allowing them to sell and service the standard NFIP policies in their own names, without bearing any of the risk, in exchange for a fee. The objective was to use insurance industry knowledge and capabilities to increase the size and geographic distribution of the NFIP policy base and to improve service to NFIP policyholders.6

In the late 1980s, it became clear that older floodprone construction was only slowly being removed from the policyholder base, and so mitigation began to be considered. The Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act of 19887 authorized funding for hazard mitigation projects aimed at reducing the risk of future flood damage or loss, such as elevating buildings, utilities, or roads; increasing the capacity of storm drainage systems; restoring wetlands or landforms that provide natural flood protection; or removing structures that are flooded repeatedly. In 1990, the NFIP implemented the Community Rating System, which rewarded community floodplain management efforts that go beyond minimum NFIP standards. Under the Community Rating System, communities receive points for taking additional actions related to flood hazard mapping and regulations, flood damage reduction, flood preparedness, and public education about flood risk in Special Flood Hazard Areas. These points are translated into discounts on insurance premiums for policyholders in that community.8

In 1993, record flooding in the upper Mississippi and lower Missouri River basins showed that only about 10 percent of properties eligible for flood insurance were insured (AIR, 2005). The NFIP Reform Act of 19949 introduced monetary penalties for lenders who do not enforce federal flood insurance requirements and denied future federal disaster assistance to property owners who allowed their flood insurance policy to lapse after receiving disaster assistance. In the late

______________

5 Public Law 93-234.

6 See http://www.fema.gov/national-flood-insurance-program/what-write-your-own-program.

7 Public Law 100-707.

8 Currently about two-thirds of all NFIP insurance policies in force are in Community Rating System communities. Approximately 56 percent of participating communities take actions that earn premium discounts of 5–10 percent, and 43 percent of communities earn discounts of 15–25 percent. Only a few communities earn premium discounts of 30–45 percent. See the Community Rating Fact Sheet, http://www.fema.gov/media-library-data/201307261605-20490-0645/communityratingsystem_2012.pdf.

9 Public Law 103-325.

FIGURE 1.5 Annual insured claims paid by the NFIP, unadjusted to a common year. SOURCE: FEMA, http://www.fema.gov/statistics-calendar-year.

1990s and early 2000s, Congress turned its attention to properties that flooded repeatedly. The Flood Insurance Reform Act of 200410 targeted mitigation funding toward the worst repetitive loss properties and denied subsidized premiums to property owners who refused mitigation assistance.

From 1987 to 2005, the NFIP had been able to use premium income to repay funds it borrowed from the U.S. Treasury to cover insured flood losses. Premium income was set to cover the historical average loss year, from 1978 to present. In 2005, hurricanes Dennis, Katrina, Rita, and Wilma struck, causing the first truly catastrophic losses to the NFIP in its history (Figure 1.5). In fact, NFIP claims from these hurricanes, which were nearly $19 billion, exceeded the total losses of the program over its history (AIR, 2005). In December 2013, the NFIP owed the Treasury $24 billion, primarily to pay claims associated with hurricanes Katrina and Sandy (GAO, 2014).

A recent review of the NFIP concluded that “the NFIP is constructed using an actuarially sound formulaic approach for the full-risk classes of policies, but is financially unsound in the aggregate because of constraints (i.e., legislative mandates) that go beyond actuarial considerations” (NRC, 2013, p. 79). The Biggert-Waters Flood Insurance Reform Act of 2012 aimed to put the NFIP on sounder financial footing by authorizing higher premiums to build up program reserves in advance of heavy loss years. The act also phased out subsidized and grandfathered insurance rates over several years. However, if a policy lapsed or the structure was sold, then the owner would then be charged the risk-based rate based on the latest flood maps.11 Premiums began increasing at the end of 2013, and some of these increases were large. The Homeowner Flood Insurance Affordability Act of 201412 rolled back these large, sudden increases and gave the NFIP the flexibility to set annual rate increases up to 18 percent for most policies.13 Although the goal of phasing in risk-based rates has not changed, the annual rate increase that the NFIP chooses will determine how long it will take to reach this goal.

______________

10 Public Law 108-264.

11 A recent analysis of the NFIP portfolio revealed that the average tenure of flood insurance is between 3 and 4 years, so this provision is likely to affect a significant number of homeowners (Michel-Kerjan et al., 2012).

12 Public Law 113-89.

13 See the overview of the Homeowner Flood Insurance Affordability Act, http://www.fema.gov/flood-insurance-reform.

This report examines methods for calculating risk-based rates for negatively elevated structures in the NFIP. Chapter 2 provides an overview of current NFIP methods for calculating flood insurance rates, as well as the flood studies and mapping used to support rate setting. Setting risk-based insurance rates depends on an accurate assessment of flood risk—the magnitude of flood loss and the likelihood that losses of that magnitude will occur. Chapter 3 compares the NFIP and other methods for assessing flood risk and calculating flood losses. Chapter 4 identifies factors that affect negatively elevated structures and changes to NFIP methods that could address them. Finally, Chapter 5 presents the committee’s conclusions and discusses data and implementation issues. Biographical sketches for the committee members (Appendix A), a glossary of technical terms used in this report (Appendix B), and a list of acronyms and abbreviations (Appendix C) appear at the end of the report.