Cardiac arrest can strike seemingly healthy individuals of any age, race, ethnicity, or gender at any time in any location, often without warning. The person who experiences a cardiac arrest may be a co-worker at the office; a child on a soccer field; a friend in a hospital; a stranger on the sidewalk; or a parent, grandparent, or spouse in a home. In an instant, a person’s pulse or blood pressure disappears, leading to a loss of consciousness and collapse, which is followed by death if treatment is not provided quickly. The risk of irreversible brain and organ injury and major disability increases the longer the delay in restoring a heart rhythm and blood flow. However, if the heart can be restarted shortly after arrest, then it is possible for individuals to make a complete recovery without any long-term effects.

Death and disability from cardiac arrest are prominent public health threats. Using conservative estimates, cardiac arrest is the third leading cause of death in the United States, following cancer and heart diseases (see Taniguchi et al., 2012). In 2013, the estimated incidence of total cardiac arrests in the United States occurring outside the hospital (i.e., out-of-hospital cardiac arrests [OHCAs]) was approximately 395,000 (Daya et al., 2015).1 The most recent estimates document an additional 200,000 cardiac arrests occurring in hospitals (i.e., in-hospital cardiac

________________

1The 2013 OHCA incidence statistic (395,000) includes patient of all ages and cardiac arrests events with both cardiac and noncardiac (e.g., trauma, drowning, and poisoning) etiologies (Daya et al., 2015). This figure is an approximation based on analysis of data from the Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium-Epistry, the limitations of which are described in Chapter 2. The calculation of incidence is available in the commissioned paper by Daya and colleagues (2015).

arrests [IHCAs]) (Merchant et al., 2011).2 Pediatric OHCAs are less common, and make up between 2 to 3 percent of all cardiac arrests in the country (Daya et al., 2015).

Despite nearly 50 years of advocacy to improve cardiac arrest treatment, overall survival rates remain low, and disability with poor neurologic and functional outcome affect communities throughout the United States. Nationally, less than 6 percent of people who experience an OHCA and 24 percent of patients who experience an IHCA survive to hospital discharge (Chan, 2015; Daya et al., 2015). One notable study found that overall survival-to-discharge rates for adults suffering OHCA in the United States had not increased during the past 30 years (Sasson et al., 2010), although emergency medical services (EMS) systems and hospitals enrolled in specific cardiac arrest registries have found positive survival trends in more recent years (Chan, 2015; Daya et al., 2015). Relative to other conditions, the cost of care and the number of productive years of lives lost due to cardiac arrest death and disability are also large (Stecker et al., 2014).

Wide disparities in cardiac arrest outcomes have also been documented. Many of these disparities may be a result of variation in local response to cardiac arrest (e.g., bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation [CPR] rates) and variation in care processes and protocols—factors that can be modified. For example, a study by Nichols and colleagues (2008) found that survival rates from OHCA ranged from 7.7 percent to 39.9 percent across 10 North American sites. Seattle and King County, Washington, have demonstrated survival rates for OHCA of 62 percent, among patients who had witnessed cardiac arrest, caused by a specific cardiac rhythm, compared to single-digit survival rates in other urban areas in the United States (Chatalas and Plorde, 2014). Risk-adjusted survival rates for IHCA also vary by 10.3 percent between bottom- and top-decile hospitals (Merchant et al., 2014). Similar variation exists for children who experience an IHCA (Jayaram et al., 2014). A wide range of factors may contribute to documented variations, including differences in patient demographics and health status, geographic chacteristics, and system-level factors affecting the quality and availability of care.

Effective treatments for specific types of cardiac arrest are known and, if more efficiently implemented on a broader basis, could avoid

________________

2The reported statistics are based on a 2011 analysis, using the most recently available data (years 2003 through 2007) from the Get With The Guidelines-Resuscitation (GWTG-R) registry. The study used three separate approaches to calculate the estimated range of annual IHCA events in the United States.

needless deaths and disability each year. Decreasing the time between the onset of cardiac arrest and the first compression is essential. Similarly, timely delivery of electrical shocks (i.e., defibrillation) can revive heart muscles for specific types of cardiac arrest and significantly increase the likelihood of survival to hospital discharge (Caffrey et al., 2002; Chan et al., 2008; Field et al., 2010). Bystander-administered CPR is associated with substantial increases in survival rates and with better neurologic outcomes after cardiac arrest (Bobrow et al., 2010; Kitamura et al., 2012; McNally et al., 2011; Sasson et al., 2010). Unfortunately, only a small fraction of the public receives CPR training in the United States annually (Anderson et al., 2014). Recent public awareness campaigns are engaging more bystanders in discussions about the importance of being prepared to respond to a cardiac arrest (see Heart Rhythm Society, 2015), and new technologies offer promising advancements in training to reduce that time to first compression and improve the quality of delivered care.

High-performing communities provide examples of how functional public health infrastructures and well-organized health system responses can facilitate timely treatments and formal transitions of care across informally defined teams (including bystanders, first responders, emergency medical technicians, paramedics, and hospital-based health care providers) to significantly improve survival and neurologic function following cardiac arrest. Within systems of care, continuous quality improvement initiatives that are based on process evaluation and observed outcomes can serve as a foundation for the development of more proactive and responsive care models, thus benefiting patients.

The solution to improving outcomes from cardiac arrest, however, does not end with better implementation of known treatments and therapies. Even if all communities and hospitals were to maximize performance based on current evidence and clinical practice guidelines, sustained support for continuing basic, clinical, and translational research is necessary to generate more effective treatments and care paradigms, and a more nimble system is needed to update care processes and treatment protocols based on evidence. Approximately 8 out of 10 cardiac arrests occur in a home setting (Vellano et al., 2015), and only 46 percent of OHCAs are witnessed by another person (Daya et al., 2015), requiring new thinking about how technologies could be used to alert possible responders to a cardiac arrest. Because approximately 70 percent of OHCAs are caused by rhythms that do not typically respond to electrical shock (Daya et al., 2015; Vellano et al., 2015), it is also important to

support and translate basic and clinical research discoveries that can provide new insights about etiology, pathophysiology, causation, and therapies. Recent advancements in available cardiac treatments (e.g., percutaneous coronary interventions, emergency cardiopulmonary bypass, cardiac revascularization, and post-resuscitation care algorithms) have also demonstrated favorable impacts on cardiac arrest outcomes. New drug combinations that target reperfusion injury may prevent cardiovascular and neurologic decline that occurs in many patients after resuscitation. Efforts to personalize medicine and improve prognostication are also leading to new models of care and reshaping discussions with patients and their families (Chan et al., 2012; Melville, 2015).

Generating the necessary momentum to foster meaningful change in cardiac arrest practice, policy, and prioritization is possible, despite many social, political, and practical challenges. Throughout the report, the committee emphasizes the need to consider the overarching system of response to cardiac arrest, which is affected by and influences other factors, including data collection, research infrastructure, public and professional training and education, program evaluation, accountability, and civic and community leadership. Leveraging existing and developing capabilities could strengthen the system of response to cardiac arrest throughout the United States, raising public awareness and stimulating action that is needed to advance the resuscitation field as a whole and preserve the length and quality of life for individuals who experience a cardiac arrest.

COMMITTEE SCOPE OF WORK

In 2013, the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association, the American Red Cross, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes of Health, and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs asked the Institute of Medicine (IOM) to conduct a consensus study on the factors currently affecting cardiac arrest treatment and outcomes in the United States. Specifically, the IOM’s Committee on the Treatment of Cardiac Arrest: Current Status and Future Directions was charged with evaluating the following five areas: CPR and use of automated external defibrillators (AEDs), EMS and hospital systems of resuscitation care, national cardiac arrest statistics, resuscitation research, and future therapies and strategies for improving

health outcomes from cardiac arrest within the next decade. Box 1-1 provides the committee’s complete statement of task.

BOX 1-1

Statement of Task

Treatment of Cardiac Arrest: Current Status and Future Directions

The Institute of Medicine will conduct a study on the current status of, and future opportunities to improve, cardiac arrest outcomes in the United States. The study will examine current statistics and variability regarding survival rates from cardiac arrest in the United States and will assess the state of scientific evidence on existing lifesaving therapies and public health strategies that could improve survival rates. Additionally, the study will include a focus on promising areas of research and next steps to improve the quality of care for cardiac arrest.

The study will focus on the following topics and questions:

- Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and use of automated external defibrillators (AEDs). What are the data on the effectiveness and use of CPR and AEDs? What is hindering use of these methods by the general public? What efforts have been conducted to improve the implementation of CPR and AEDs by the general public? What training efforts should be explored in schools or through other public initiatives?

- EMS and hospital resuscitation systems of care. What is the quality and performance level of out-of-hospital EMS providers and in-hospital resuscitation care teams? What is known about whether each patient is getting the care that they need? What challenges and barriers exist for teams and systems to more quickly implement best practices?

- Resuscitation research. What is the state of resuscitation research in the United States, including research on therapeutic hypothermia, emergency cardiopulmonary bypass resuscitation, and aggressive post-resuscitation critical care for cardiac arrest patients? Where are the research, technology transfer and innovation, and implementation gaps?

- Next steps. What are the new therapies and strategies on the “near horizon” (next 5 to 10 years) that hold the most promise to significantly enhance survival rates or to be the next paradigm in resuscitation care? How can resuscitation science discoveries be optimized for the rapid implementation of new therapies?

To respond to this charge, the IOM convened a committee of 19 experts with backgrounds in clinical medicine, health care services and delivery, epidemiology, statistics, research methods, health disparities, public education and outreach, cardiac electrophysiology, and ethics (see Appendix C). The committee held five meetings and two public workshops during the course of its work (see Appendix B) to solicit input from a variety of stakeholders and experts. In addition to input received through public workshops, the committee examined the available scientific literature, and also commissioned analyses of the most recently available data from the following registries: the Cardiac Arrest Registry to Enhance Survival, the Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium Epistry, and the Get With The Guidelines-Resuscitation registry.

Although both prevention and treatment of cardiac arrest are important to reduce the impact of cardiac arrest in the United States, the committee’s scope of work was explicitly limited to an analysis of how to improve outcomes following cardiac arrest. Additionally, because of concerns about the quality and availability of evidence about cardiac arrest, in general, the committee limited its analysis of treatments up through hospital discharge and outcomes through 90-days post discharge, which excluded a detailed analysis of rehabilitation. The committee acknowledges the important roles that prevention and rehabilitation play and notes that both topics merit separate and dedicated analyses. With this in mind, elements related to prevention and rehabilitation are mentioned throughout this report. Some of the committee’s recommendations related to cardiac arrest treatment will also affect cardiac arrest prevention, as well as rehabilitation.

The lack of data and currently available resources to study cardiac arrest etiology, causation, and treatment presented substantial barriers to the committee when trying to determine the effectiveness of either new or existing therapies. Moreover, the committee did not want to duplicate the work of guideline-issuing organizations that are currently conducting large-scale and comprehensive literature reviews for all existing cardiac arrest treatment and care protocols. As such, this report focuses more heavily on identifying short- and long-term strategies to propel the overall field of resuscitation. This includes discussions about strategies to encourage the development of new therapies and treatments, increase public awareness and willingness to intervene, as well as catalyze immediate system-level responses and quality improvement activities related to cardiac arrest in communities.

DEFINING CARDIAC ARREST

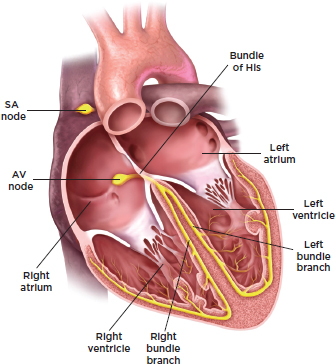

Cardiac arrest is a severe malfunction or cessation of the electrical and mechanical activity of the heart.3,4 Under normal circumstances, the sinoatrial node initiates and sends an electrical signal to the right and left atria, causing the atria to contract and pump blood into the ventricles (see Figure 1-1). The electrical signal then travels from the atrioventricular node to the right and left ventricles, causing them to contract in a coordinated sequence and pump blood out of the heart to the lungs and the rest of the body. When the signal dissipates, the ventricles relax, and the process begins again after a normal delay.

Although the terms are often used interchangeably in the media and casual conversation, cardiac arrest is different and medically distinct from a heart attack (i.e., a myocardial infarction). Cardiac arrest results in almost instantaneous loss of consciousness and collapse, which will uniformly lead to death if not promptly reversed. Other symptoms may include absent or abnormal breathing (e.g., gasping or agonal breaths). Cardiac arrest may be due to a primary loss of cardiac pumping function, a variety of blood vessel-related factors (e.g., mechanical obstruction to arrest, usually as a consequence of a disturbance in the electrical activity of the heart that results in loss of mechanical function [commonly referred to as “sudden cardiac arrest”]), and to a lesser extent on causes that are primarily vascular or respiratory.

Compare this to a heart attack, a condition in which blood flow to an area of the heart is blocked by a narrowed or completely obstructed coronary artery. This causes inadequate oxygenation and subsequent injury or death to a portion of the heart. Acute symptoms of a heart attack include chest pain, shortness of breath, sweatiness, and dizziness, but do not necessarily include the pattern of immediate loss of consciousness that characterizes a cardiac arrest. A heart attack, large or small, can affect the electrical signaling and cause a cardiac arrest. However,

________________

3In its broadest definition, the term “cardiac arrest” refers to the loss of blood flow needed to maintain organ function and ultimate viability.

4Sudden cardiac death is defined as death due to a cardiac etiology or cardiac involvement in a noncardiac disorder, in a person with or without a known preexisting disease, and in whom the time and mode of death are unexpected (Myerburg and Castellanos, 2015). The committee selected to use the term “cardiac arrest” rather than “sudden cardiac death” to emphasize the broad range of factors that affect treatment of a clinical event as well as health outcomes beyond survival or death.

FIGURE 1-1 Anatomy of the heart’s electrical system.

NOTE: AV = atrioventricular; SA = sinoatrial. The bundle of His is “the specialized tissue in the heart that transmits the electrical impulses and helps synchronize contraction” (Roquin, 2006, p. 480).

SOURCE: Adapted illustration reprinted by the IOM, with permission from Medmovie Copyright 2015.

a cardiac arrest does not cause a heart attack. Table 1-1 provides an overview of the differences between cardiac arrest and heart attack.

The distinction between cardiac arrest and heart attack is important because the goals and timing of treatment and the individuals qualified to perform specific treatments for these conditions are very different. The primary goals of cardiac arrest treatment are to facilitate return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) and to avoid death and any physical or neurological damage.5 This requires reestablishing circulation (either manual or spontaneous) as quickly as possible, because survival decreases by approximately 10 percent per minute following arrest (Boineau, 2014).

________________

5Chapter 5 provides a more comprehensive explanation of possible outcomes from cardiac arrest.

TABLE 1-1 Differences Between Cardiac Arrest and Heart Attack

| Characteristics | Cardiac Arrest | Heart Attack |

| Average age | 63 (OHCA)a:65 (IHCA)b | 65 (men): 72 (women)c |

| Male:female incidence ratio | 3:2a,b; occurs in all ages, although frequency increases with increasing age | 2:1c; less likely to occur in people younger than 35 years of age |

| Immediate cause | Cessation of mechanical activity of the heart, caused by a malfunction in the heart’s electrical system | Blockage or significant narrowing of a coronary artery, causing tissue damage to an area of heart muscle due to lack of oxygen |

| Early warning symptoms | Some patients may experience palpitations, dizziness, chest pain, or shortness of breath momentarily before loss of consciousness and collapse | Patients may experience chest pain or upper body discomfort, unusual fatigue, weakness, nausea, shortness of breath; symptoms may occur days or weeks before |

| Loss of pulse, blood pressure, consciousness | Yes—in all cases | Heart attack may lead to cardiac arrest |

| Breathing | No, although gasping and agonal breaths may be mistaken for normal breathing | Yes |

| Cardiac rhythm | Characterized by complete lack of a heart rhythm or one incapable of generating a mechanical heart beat | May be accompanied by arrhythmias that do not cause loss of mechanical heart beats |

| Characteristics | Cardiac Arrest | Heart Attack |

| Risk factors/medical history | Noncardiac causes include electrolyte imbalance, severe blood loss, drug use, and drowning | |

| Treatment |

|

|

NOTE: IHCA = in-hospital cardiac arrest; OHCA = out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.

SOURCES: aVellano et al., 2015; bChan, 2015; cMozaffarian et al., 2015.

The likelihood of irreversible brain injury resulting in brain death, coma, vegetative state, or significant neurologic disability increases with delay in ROSC. Alternatively, neurologic and organ ischemia are less likely with a heart attack unless blood pressure is severely decreased. The primary goals of treatment for a heart attack are to reopen blocked arteries and restore blood flow to the heart before irreversible death of the heart muscle is present—usually 20 to 40 minutes after onset of inadequate oxygenation (Pierard, 2003).

Unlike with a heart attack, bystanders can perform CPR to treat cardiac arrest. CPR mechanically restores blood circulation and traditionally includes “integrated chest compressions and rescue breathing [i.e., mouth-to-mouth resuscitation]” to optimize circulation and oxygenation until ROSC is achieved (Travers et al., 2010, p. s677). The exact CPR performance specifications depend on the rescuer (e.g., some training courses now teach compression-only CPR, whereas courses for health professionals still emphasize ventilation and chest compression). Regardless of method, the basic actions can be performed by most adolescents and adults and should be delivered as soon as possible after recognition of a cardiac arrest. Although CPR can provide sufficient blood flow to protect the heart and the brain for some minutes—and can be effective in attaining ROSC—CPR typically is used to buy critical time until more effective treatments can be initiated.

A second treatment option is defibrillation, which is the provision of an electrical shock to the heart muscle, with the intent of restoring normal cardiac electrical activity and contractions (Travers et al., 2010). AEDs are devices that can be used by bystanders, as well as trained professionals. An AED analyzes heart rhythms and advises rescuers to administer a shock or resume CPR as appropriate. The devices are designed to be user friendly, provide easy-to-follow visual and auditory signs, and prevent the accidental or intentional administration of inappropriate shocks.

Not all cardiac arrests will respond to defibrillation. Four primary alterations in electrical activity of the heart may be associated with cardiac arrest: ventricular fibrillation (VF), pulseless ventricular tachycardia (pVT), pulseless electrical activity (PEA), and asystole (see Table 1-2). VF results from a faulty electrical signal in heart tissue resulting in loss of a coordination of contracting heart cells, and pVT is a failure of contraction during a very rapid heartbeat, originating in the ventricles. Cardiac arrest may also occur as a result of a primary mechanical function failure, in which the electrical signal fails to initiate a mechanical response (PEA) or when there is complete loss of an electrical signal so that no mechanical response can occur (asystole). “Shockable” arrhythmias (i.e., pVT and VF) may respond to defibrillation or electrical cardioversion, whereas “nonshockable” arrhythmias (i.e., PEA and asystole) usually do not. In addition to mechanism, cardiac arrest is also generally categorized by location of the arrest—OHCA and IHCA). The majority of both OHCAs and IHCAs are attributed to nonshockable rhythms, which may require development of new treatments and therapies to significantly improve outcomes, as discussed in Chapter 6.

In the context of OHCA, emergency medical systems professionals and/or bystanders may perform basic life support (BLS), which includes recognition of cardiac arrest, activation of the emergency response system, and performance of CPR and defibrillation. Advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) is used to complement BLS interventions, usually during transport to medical facilities by treating the cardiac arrest and stabilizing patients who achieve ROSC (Neumar et al., 2010). ACLS can be performed in the field or in hospital settings by trained professionals and often includes CPR, intravenous medications, advanced airway management, and physiological monitoring (Neumar et al., 2010). The effectiveness of specific ACLS interventions is debated, as described in greater detail in Chapter 4.

TABLE 1-2 The Types and Characteristics of Primary Cardiac Arrest Arrhythmias

| Ventricular Fibrillation | Pulseless Ventricular Tachycardia | Pulseless Electrical Activity* | Asystole | |

| Definition | Uncoordinated electrical activation of heart, resulting in loss of organized contraction of the ventriclesa | Organized electrical activation of heart, with absent or ineffective contraction of the ventricles, due to rate or extent of diseasea | The heart’s electrical activity is present, often slow and/or irregular, but the signal fails to initiate a mechanical response in the cells, resulting in no ventricle contractiona | Absence of electrical activity of the heart; no signal to initiate contraction of the ventriclesa |

| ECG appearance | Grossly irregular electrical pattern on ECG, without identifiable QRS complexesa | Regular QRS complexes, usually wide and fasta | Usually wide QRS complexes, often slow and irregular;a sometimes narrow QRS complexes | No electrical activity—flat linea |

| Electrical activity | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Palpable pulse | No | Usually not; occasionally present but weak | No | No |

| Responds to shock | Yes (usually) | Yes (usually) | No | No |

| Total CA in adults by first documented CA rhythm (%)** | OHCA 22.0b |

OHCA Included with VF |

OHCA 23.5b |

OHCA 46.9b |

| IHCA 10.0c |

IHCA 7.4c |

IHCA 54.6c |

IHCA 28.0c |

|

| Ventricular Fibrillation | Pulseless Ventricular Tachycardia | Pulseless Electrical Activity* | Asystole | |

| Total CA in children by first documented CA rhythm (%) | OHCA 4.9b |

OHCA Included in VF |

OHCA 12.9b |

OHCA 68.9b |

| IHCA 14.0d |

IHCA Included in VF |

IHCA 24.0d |

IHCA 40.0d |

|

| Adult patients with first documented CA rhythm who survive to hospital discharge (%) | OHCA 28.7b |

OHCA Included in VF |

OHCA 8.7b |

OHCA 2.0b |

| IHCA 46.2c |

IHCA 44.9c |

IHCA 19.8c |

IHCA 20.2c |

|

* This term was previously “electrical-mechanical dissociation.”

** This table does not present a small percent of unknown OHCA rhythms.

NOTE: CA = cardiac arrest; ECG = electrocardiogram; IHCA = in-hospital cardiac arrest; OHCA = out-of-hospital cardiac arrest; QRS complexes = “the series of deflections in an electrocardiogram that represent electrical activity generated by ventricular depolarization prior to contraction of the ventricles” (Merriam-Webster.com, 2015); VF = ventricular fibrillation.

SOURCES: aMann et al., 2014; bDaya et al., 2015; cChan, 2015; dNadkarni et al., 2006.

Upon ROSC, post-arrest care is administered to reduce the risks of post-cardiac arrest syndrome, which includes cerebral and cardiac damage and dysfunction (Morrison et al., 2013; Neumar et al., 2008; Stub et al., 2011). Early post-arrest care includes prognosis assessments and integrated treatments designed to “optimize cardiopulmonary function and vital organ perfusion,” transport a patient to an appropriate care facility (either hospital or unit within a hospital), and “identify and treat the precipitating causes of arrest and prevent recurrent arrest” (Peberdy et al., 2010, p. s768). Treatments and therapies may include oxygenation and ventilation, targeted temperature management (e.g., hypothermia), cardiovascular management, cardiac catheterization, hemodynamic support, vasopressor therapies, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, anticonvulsants, and metabolic management. Post-arrest care protocols also differ for OHCA and IHCA. For example, in post-arrest care, targeted temperature management is rarely used after IHCA, which may be due to

concerns of additional acute illnesses in these patients that may have unpredictable systemic responses to widespread temperature changes (Mikkelsen et al., 2013). Although the majority of post–cardiac arrest care is delivered in the hospital setting, EMS personnel may also provide some elements of post-arrest care, such as targeted temperature management and administration of specific pharmaceuticals and intravenous saline (Pinchalk, 2010). These treatment and therapies, which are described in greater detail in Chapters 5 and 6, have varying degrees of effectiveness.

THE CARDIAC ARREST CHAIN OF SURVIVAL

In 1991, the American Heart Association introduced the “chain of survival” model (Cummins et al., 1991) (see Table 1-2), which has served as the dominant operational model for the resuscitation field since its publication and has been influential in affecting the delivery of efficient and effective care within discrete systems of some pioneering communities.

The chain, which originally evolved in the resuscitation field for use by EMS systems, includes five key, time-sensitive, and interdependent links: early access, early CPR, early defibrillation, early ACLS, and early post-resuscitative care (see Box 1-2). All of these links must rapidly and efficiently occur, sometimes sequentially or in parallel, to maximize the likelihood of survival and favorable neurologic and functional outcomes from cardiac arrest. The likelihood of successful resuscitation decreases if any link is delayed or improperly performed. Moreover, “separate specialized programs are necessary to develop strength in each link” (Cummins et al., 1991, p. 1832). In recent decades, many organizations,

FIGURE 1-2 The cardiac arrest chain of survival.

NOTE: ACLS = advanced cardiac life support; CPR = cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

SOURCE: Resuscitation Academy, 2014.

BOX 1-2

Definitions of the Five Links in the OHCA Chain of Survival

Early Access: Early access to care comprises all events that are initiated after the patient’s collapse until the arrival of EMS providers. Access includes recognition of the event, activation of the emergency medical system (i.e., calling 9-1-1), discussion with a dispatcher, and the decision to send an emergency response vehicle (Cummins et al., 1991).

Early Advanced Cardiac Life Support: Beyond CPR and defibrillation, paramedics may need to deliver early advanced care life support (e.g., drug therapies, airway management, and other intravenous treatment and monitoring) to achieve spontaneous resuscitation (Cummins et al., 1991).

Early CPR: Early CPR includes the initiation of basic CPR immediately after recognition of the event. It may overlap with efforts to activate the EMS system (Cummins et al., 1991).

Early Defibrillation: Early defibrillation includes the provision of electrical shock to the heart to reestablish a normal, spontaneous heart rhythm (Cummins et al., 1991). Several options for rapid defibrillation exist, including automated external, semi-automated external, or manual defibrillators (AHA, 2000).

Early Post-Resuscitative Care: Early and effective post-arrest care following resuscitation has the potential to restore and preserve the cognitive and functional health status of cardiac arrest patients. It may include more advanced treatments, such as prognosis assessments, oxygenation and ventilation, targeted temperature management (e.g., hypothermia), cardiovascular management, cardiac catheterization, hemodynamic support, vasopressor therapies, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, and metabolic management (Neumar et al., 2010).

departments, and individuals have developed myriad strategies and interventions to strengthen the chain, specifically aimed at improving recognition of cardiac arrest and increasing the timeliness and quality of care. For example, some communities have implemented dispatcher-assisted CPR training to improve rates of bystander CPR performance. Other communities have implemented programs designed to promote high-quality CPR by EMS personnel and have demonstrated significant improvement in patient outcomes.

The principles of early recognition and early treatment are relevant to both OHCA and IHCA. Although the basic concepts involved in response to OHCA and IHCA are similar, there are specific differences between the events—both in terms of the health of the patient population and the treatment protocols—and these differences can affect the links within the chain and the provision of care at each stage. Patients who have an arrest in a hospital, particularly those in critical care units, are sicker than the average person who has an arrest in a community setting, and the arrest is frequently due to the heart’s response to severe systemic illness rather than being the primary event. Thus, IHCA may be marked by observable deterioration of a patient in the hours leading up to the arrest, allowing for earlier and different interventions (Chan, 2015; Morrison et al., 2013). Response times are shorter and medical personnel can provide advanced screenings and immediate and simultaneous treatments in team environments in response to IHCA.

Because the chain is an operational model, it has a limited ability to identify objectives for the broader resuscitation field or strategies to synchronize interrelated components within the field. Furthermore, the current chain of survival model does not explicitly emphasize the importance of proactive leadership; transparency of, and accountability for, care quality and outcomes; or mechanisms to promote continual evaluation of existing treatments and systems of response. For example, the positive trends of cardiac arrest survival in selected communities may be a result of better feedback to EMS personnel, particularly in regard to meeting performance standards of care (Chan et al., 2014; McNally et al., 2011). Although the chain of survival does not exclude these actions, it also does not explicitly identify specific key actions to encourage efforts to enhance cardiac arrest outcomes.

A SYSTEMS FRAMEWORK

Effective care for cardiac arrest requires a proactive and coordinated system of response. Across this system, various actors may deliver care in succession or simultaneously. These actors may include the general public; local emergency services organizations; health care facilities; federal, state, and local health, education, and emergency services agencies; national nonprofit organizations; schools; and employers. Regardless of the order of care provided, high-quality performance and treatments

must be maintained across all actors and settings to ensure patient survival and good neurologic and functional outcomes following cardiac arrest.

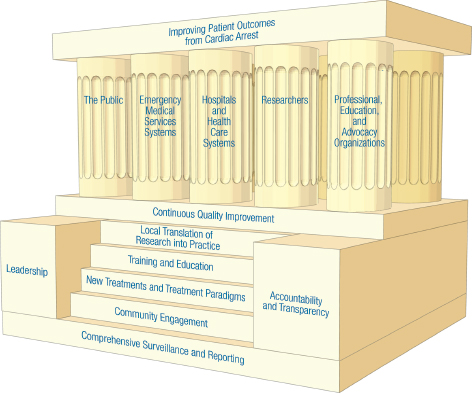

To facilitate productive discussion between federal, state, local, and community representatives, a comprehensive systems-level framework is needed to guide the development of cohesive short- and long-term strategies, which are necessary to reduce the public burden of cardiac arrest. Figure 1-3 illustrates a systems-level framework that can be used to identify and describe the relationships between critical components (i.e., actions and actors) that affect treatment of cardiac arrest. One goal—to increase the likelihood of survival with good neurologic function for any person who suffers a cardiac arrest (i.e., improved patient outcomes)—provides the roof. Together, the foundation and pillars are part of an integral, comprehensive system-level response that is necessary to revitalize the resuscitation field and improve population health and patient outcomes from cardiac arrest in the short and long terms.

Effective cardiac arrest response requires the actions of five groups (represented by the five columns in the figure) that directly and indirectly affect patient outcomes. The public includes bystanders, who are at the forefront of the response and have the opportunity to report the event and initiate the response. The public also includes individuals who experience a cardiac arrest, friends, and families, along with individuals in industry, the workplace, schools, care facilities, and community organizations. EMS systems include 911 call takers, dispatchers, first responders, emergency medical technicians, and paramedics, who respond to cardiac arrests and transport patients to local hospitals and emergency medical facilities after initiating resuscitation treatment. Similarly, individuals within EMS systems have the opportunity to instruct bystanders on how to administer CPR through dispatcher-assisted CPR.6 Hospitals and broader health care systems (which

________________

6Dispatcher-assisted CPR (also referred to as dispatcher-assisted bystander CPR, just-in-time instruction, and telecommunicator CPR) is a term that includes the identification of cardiac arrest and the provision of CPR instructions to a 911 caller prior to the arrival of EMS providers at the scene of a cardiac arrest (see Chapter 4). Because dispatchers and 911 call takers may not be the same person, especially in large 911 centers, “telecommunicator” is used as an umbrella term to refer to any individual who works in a 911 center and has responsibility for receiving calls and/or sending help. To remain consistent with recent Utstein core measures and with terminology generally used in emergency medicine and by the public, this report uses the term “dispatcher-assisted CPR” to mean CPR instruction provided over a phone to a rescuer by a trained individual.

FIGURE 1-3 A unifying framework for improving patient outcomes from cardiac arrest.

NOTES: This figure is based on a figure from the Institute of Medicine’s Crisis Standards of Care series, which proposed a framework for catastrophic disaster response to assist in crisis standards of care planning (IOM, 2013, p. 18). Although the purpose and specific elements are different, the committee found the general approach useful in framing the principles, actions, and actors relevant to improved cardiac arrest response.

may include rehabilitation services) respond to cardiac arrests, provide essential post-arrest care for patients, and facilitate critical care transitions between EMS systems and various departments within the hospitals. Basic, clinical, and translational researchers generate hypotheses and new insights about the mechanisms and pathophysiology of cardiac arrest, identifying novel pathways that can lead to the delivery of innovative treatments and treatment models. Finally, professional, training, and advocacy organizations can provide opportunities to educate and train various actors across the system, promoting valuable interdisciplinary dialogue, better informed policies, and a culture of action through increased accountability. Improved patient outcomes are more likely when

these actors come together to collaborate and coordinate their activities to strengthen the field and kindle progress.

The foundation of the figure comprises six steps, each representing fundamental key actions: (1) comprehensive surveillance and reporting, (2) community engagement, (3) new treatments and treatment paradigms, (4) training and education, (5) local translation of research into practice, and (6) continuous quality improvement programs. Leadership, along with accountability and transparency, serve as the cornerstones that establish the position and direction of the entire structure.

Comprehensive Surveillance and Reporting

Given the large health burden of cardiac arrest, a national responsibility exists to facilitate dialogue about cardiac arrest that is informed by comprehensive data collection and timely reporting and dissemination of information. Reliable and accurate data are needed to empower states, local health departments, EMS systems, health care systems, and researchers to develop metrics, identify benchmarks, revise education and training materials, and implement best practices. Furthermore, increasing public awareness about disparities in care and opportunities to improve outcomes can lead to greater public engagement in education and training, larger advocacy networks, and stronger community leadership efforts related to cardiac arrest.

Community Engagement

The urgent nature of cardiac arrest and the risks of mortality and disability without immediate response imply a societal obligation of bystanders to be prepared and willing to deliver basic life support before the arrival of professional emergency responders. Communities can foster a culture of action by promoting easy access to CPR and AED training and active engagement in response to cardiac arrest. Communities can also cultivate community engagement through public advocacy, local awareness events and campaigns, and leadership opportunities that create a platform for dialogue within the community.

New Treatments and Treatment Paradigms

Strategic investment in research will increase the understanding of disease processes that can expand the availability of new therapies and

drive beneficial changes in the resuscitation field. Traditional treatments for cardiac arrest do not fully account for the complex pathophysiology of cardiac arrests. For example, although an effective treatment for some cardiac arrest rhythms (e.g., pVT and VF), defibrillation is not effective for all cardiac arrest rhythms (e.g., those with PEA and asystole) nor does it address the effects of global ischemia. Treatment strategies for cardiac arrest need to evolve further based on new information generated from basic and clinical research.

Training and Education

Successful resuscitation following cardiac arrest requires a series of synchronized, exacting responses, often involving complex transitions between different caregivers, including bystanders, trained first responders, EMS personnel, and health care providers. Given the need for reliable competency and consistent care quality to improve health outcomes across sites of care, all caregivers must be educated about the burden of cardiac arrest and trained (and retrained) to provide rapid and effective treatment for cardiac arrest.

Local Translation of Research into Practice

Efficient translation of resuscitation science and research into care delivery practices is essential to optimize patient outcomes from cardiac arrest. National guidelines should be viewed as baseline standards from which regional and local practice and care delivery protocols may evolve based on emerging evidence (e.g., continuous monitoring of local data and published literature), local challenges (e.g., disparities in outcomes and low bystander response rates), state regulation and governance structure of EMS and health care systems, and available resources (e.g., trained EMS or health care personnel, and funding).

Continuous Quality Improvement Programs

Widespread adoption of continuous quality improvement programs throughout the field of resuscitation would encourage data collection across all sites of care, enable comparisons within and between EMS and health care systems, and lead to the identification of best practices to improve population health and patient outcomes following cardiac arrest. Public policies encouraging such programs for other systems of care

(e.g., learning health care systems) should serve as models for the field of resuscitation, which includes a broader range of individuals responding to cardiac arrest.

Leadership

Cardiac arrest outcomes are affected by leadership across a wide range of settings, including federal agencies, state and local government (including health departments), EMS systems, health care organizations, and community clinics and advocacy organizations. Communities that have demonstrated higher cardiac arrest survival rates and favorable neurologic outcomes typically have strong civic, EMS, and health care system leaders, who establish accountability for these outcomes to their communities through increased public awareness efforts, widespread training in CPR and AED use, and sustained investment in outcome measurement, data reporting, and self-assessment. With appropriate leadership, effective treatments and strategies can be adopted in other communities to save thousands more lives across the country each year.

Accountability and Transparency

Enhanced accountability and transparency can increase operational effectiveness and efficiency by building trust among stakeholders, engaging individuals and organizations in continuous quality activities, and fostering innovation. Currently, the resuscitation field lacks appropriate transparency and accountability for cardiac arrest incidence and outcomes. As more detailed and larger data sets become available, new opportunities will emerge to increase public awareness, enhance training across different sectors, and modify local system treatment protocols and service delivery models related to cardiac arrest. These opportunities will require explicit responsibility to collect and disseminate data to the public in order to establish accountability for system performance through various social and policy mechanisms.

OVERVIEW OF THE REPORT

This report examines the complete system of response to cardiac arrest in the United States and identifies opportunities through existing and new treatments, strategies, and research to improve survival and

recovery of patients. This chapter provides an overview of issues that are discussed throughout the report, highlights important overarching themes, and suggests a more explicit systems framework to help guide discussions and strategies to advance the field of resuscitation and to improve cardiac arrest outcomes. Chapter 2 discusses the public health burden of cardiac arrest, summarizes available data registries for the evaluation of cardiac arrest, and suggests opportunities to improve cardiac arrest surveillance in the United States. Chapter 3 explores barriers to public engagement and education and training opportunities that encourage active response to cardiac arrest in the community. Chapter 4 examines current EMS system responses to improve outcomes from OHCA. Challenges to providing high-quality resuscitation for IHCA and postarrest care and high-quality resuscitation for IHCA are discussed in Chapter 5. Chapter 6 considers current research infrastructure and highlights innovative research methods, design, and technology to advance the science of resuscitation. Finally, Chapter 7 highlights the key messages within this report, and concludes with recommendations and priorities, aimed at individual citizens, government agencies, professional organizations, and private industry, to improve health outcomes from sudden cardiac arrest across the United States.

REFERENCES

AHA (American Heart Association). 2000. Part 12: Science to survival: Strengthening the chain of survival in every community. Circulation 102(Suppl 1):I358-I370.

Anderson, M. L., M. Cox, S. M. Al-Khatib, G. Nichol, K. L. Thomas, P. S. Chan, P. Saha-Chaudhuri, E. L. Fosbol, B. Eigel, B. Clendenen, and E. D. Peterson. 2014. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation training rates in the United States. JAMA Internal Medicine 174(2):194-201.

Bobrow, B. J., D. W. Spaite, R. A. Berg, U. Stolz, A. B. Sanders, K. B. Kern, T. F. Vadeboncoeur, L. L. Clark, J. V. Gallagher, J. S. Stapczynski, F. LoVecchio, T. J. Mullins, W. O. Humble, and G. A. Ewy. 2010. Chest compression-only CPR by lay rescuers and survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Journal of the American Medical Association 304(13):1447-1454.

Boineau, R. 2014. NHLBI-related activities on the treatment of cardiac arrest: Current status and future directions. Presented at the third meeting of the IOM’s Committee on Treatment of Cardiac Arrest: Current Status and Future Directions, Washington, DC.

Caffrey, S. L., P. J. Willoughby, P. E. Pepe, and L. B. Becker. 2002. Public use of automated defibrillators. New England Journal of Medicine 347(16):1242-1247.

Chan, P. S. 2015. Public health burden of in-hospital cardiac arrest. Paper commissioned by the Committee on the Treatment of Cardiac Arrest: Current Status and Future Directions. http://www.iom.edu/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2015/GWTG.pdf (accessed June 30, 2015).

Chan, P. S., H. M. Krumholz, G. Nichol, and B. K. Nallamothu. 2008. Delayed time to defibrillation after in-hospital cardiac arrest. New England Journal of Medicine 358(1):9-17.

Chan, P. S., J. A. Spertus, H. M. Krumholz, R. A. Berg, Y. Li, C. Sasson, and B. K. Nallamothu. 2012. A validated prediction tool for initial survivors of in-hospital cardiac arrest. Archive of Internal Medicine 172(12):947-953.

Chan, P. S., B. McNally, F. Tang, and A. L. Kellermann. 2014. Recent trends in survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in the United States. Circulation 130(21):1876-1882.

Chatalas, H., and M. Plorde, eds. 2014. Division of Emergency Medical Services 2014 annual report to the King County Council. Seattle, WA: Emergency Medical Services Division of Public Health Department—Seattle and King County. http://www.kingcounty.gov/healthservices/health/%7e/media/health/publichealth/documents/ems/2014AnnualReport.ashx (accessed June 8, 2015).

Cummins, R. O., J. P. Ornato, W. H. Thies, P. E. Pepe. 1991. Improving survival from sudden cardiac arrest: The “chain of survival” concept. A statement for health professionals from the Advanced Cardiac Life Support Subcommittee and the Emergency Cardiac Care Committee, American Heart Association. Circulation 83(5):1832-1847.

Daya, M., R. Schmicker, S. May, and L. Morrison. 2015. Current burden of cardiac arrest in the United States: Report from the Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium. Paper commissioned by the Committee on the Treatment of Cardiac Arrest: Current Status and Future Directions. http://www.iom.edu/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2015/ROC.pdf (accessed June 30, 2015).

Field, J. M., M. F. Hazinski, M. R. Sayre, L. Chameides, S. M. Schexnayder, R. Hemphill, R. A. Samson, J. Kattwinkel, R. A. Berg, F. Bhanji, D. M. Cave, E. C. Jauch, P. J. Kudenchuk, R. W. Neumar, M. A. Peberdy, J. M. Perlman, E. Sinz, A. H. Travers, M. D. Berg, J. E. Billi, B. Eigel, R. W. Hickey, M. E. Kleinman, M. S. Link, L. J. Morrison, R. E. O’Connor, M. Shuster, C. W. Callaway, B. Cucchiara, J. D. Ferguson, T. D. Rea, and T. L. Vanden Hoek. 2010. Part 1: Executive summary: 2010 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation 122(18 Suppl 3):S640-S656.

Heart Rhythm Society. 2015. Sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) awareness. http://www.hrsonline.org/News/Sudden-Cardiac-Arrest-SCA-Awareness#axzz3dLw2mEkD (accessed June 17, 2015).

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2013. Crisis standards of care: A systems framework for catastrophic disaster response. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Jayaram, N., J. A. Spertus, V. Nadkarni, R. A. Berg, F. Tang, T. Raymond, A. M. Guerguerian, and P. S. Chan. 2014. Hospital variation in survival after pediatric in-hospital cardiac arrest. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality Outcomes 7(4):517-523.

Kitamura, T., T. Iwami, T. Kawamura, M. Nitta, H. Nagao, H. Nonogi, N. Yonemoto, and T. Kimura, for the Japanese Circulation Society Resuscitation Science Study Group. 2012. Nationwide improvements in survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in Japan. Circulation 126(24):2834-2843.

Mann, D. L., D. P. Zipes, P. Libby, and R. O. Bonow. 2014. Braunwald’s heart disease: A textbook of cardiovascular medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences.

McNally, B., R. Robb, M. Mehta, K. Vellano, A. L. Valderrama, P. W. Yoon, C. Sasson, A. Crouch, A. B. Perez, R. Merritt, and A. Kellermann. 2011. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest surveillance—Cardiac Arrest Registry to Enhance Survival (CARES), United States, October 1, 2005–December 31, 2010. MMWR Surveillance Summary 60(8):1-19.

Melville, N. A. 2015. “Personalized” CPR increases survival from cardiac arrest. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/838730 (accessed June 15, 2015).

Merchant, R. M., R. A. Berg, L. Yang, L. B. Becker, P. W. Groeneveld, and P. S. Chan; for the American Heart Association’s Get With The Guidelines-Resuscitation Investigators. 2014. Hospital variation in survival after in-hospital cardiac arrest. Journal of the American Heart Association 3(1):1-7.

Merchant, R. M., L. Yang, L. B. Becker, R. A. Berg, V. Nadkarni, G. Nichol, B. G. Carr, N. Mitra, S. M. Bradley, B. S. Abella, and P. W. Groeneveld. 2011. Incidence of treated cardiac arrest in hospitalized patients in the United States. Critical Care Medicine 39(11):2401-2406.

Merriam-Webster.com. 2015. Definition of QRS complex. http://www.merriamwebster.com/medical/qrs%20complex (accessed June 17, 2015).

Mikkelsen, M. E., J. D. Christie, B. S. Abella, M. P. Kerlin, B. D. Fuchs, W. D. Schweickert, R. A. Berg, V. N. Mosesso, F. S. Shofer, J. F. Gaieski, for the American Heart Association’s Get With The Guidelines-Resuscitation Investigators. 2013. Use of therapeutic hypothermia after in-hospital cardiac arrest. Critical Care Medicine 41(6):1385-1395.

Morrison, L. J., R. W. Neumar, J. L. Zimmerman, M. S. Link, L. K. Newby, P. W. McMullan, Jr., T. V. Hoek, C. C. Halverson, L. Doering, M. A. Peberdy, and D. P. Edelson, for the American Heart Association Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee; the Council of Cardiopulmonary, Critical Care, Perioperative and Resuscitation; the Council on Cardiovascular and

Stroke Nursing; the Council on Clinical Cardiology; and the Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease. 2013. Strategies for improving survival after in-hospital cardiac arrest in the United States: 2013 consensus recommendations: A consensus statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 127(14):1538-1563.

Mozaffarian D., E. J. Benjamin, A. S. Go, D. K. Arnett, M. J. Blaha, M. Cushman, S. de Ferranti, J-P. Després, H. J. Fullerton, V. J. Howard, M. D. Huffman, S. E. Judd, B. M. Kissela, D. T. Lackland, J. H. Lichtman, D. Lisabeth, S. Liu, R. H. Mackey, D. B. Matchar, D. K. McGuire, E. R. Mohler III, C. S. Moy, P. Muntner, M. E. Mussolino, K. Nasir, R. W. Neumar, G. Nichol, L. Palaniappan, D. K. Pandey, M. J. Reeves, C. J. Rodriguez, P. D. Sorlie, J. Stein, A. Towfighi, T. N. Turan, S. S. Virani, J. Z. Willey, D. Woo, R. W. Yeh, M. B. Turner; on behalf of the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. 2015. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2015 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 131:e29-e32.

Myerburg, R. J., and A. Castellanos. 2015. Cardiac arrest and sudden cardiac death. Chapter 39 in R. O. Bonow, D. L. Mann, D. P. Zipes, P. Libby, eds., Braunwald’s heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine, 10th ed. Oxford, UK: Elsevier.

Nadkarni, V. M., G. L. Larkin, M. A. Peberdy, S. M. Carey, W. Kaye, M. E. Mancini, G. Nichol, T. Lane-Truitt, J. Potts, J. P. Ornato, and R. A. Berg. 2006. First documented rhythm and clinical outcome from in-hospital cardiac arrest among children and adults. Journal of the American Medical Association 295(1):50-57.

Neumar, R. W., J. P. Nolan, C. Adrie, M. Aibiki, R. A. Berg, B. W. Bottiger, C. Callaway, R. S. Clark, R. G. Geocadin, E. C. Jauch, K. B. Kern, I. Laurent, W. T. Longstreth, Jr., R. M. Merchant, P. Morley, L. J. Morrison, V. Nadkarni, M. A. Peberdy, E. P. Rivers, A. Rodriguez-Nunez, F. W. Sellke, C. Spaulding, K. Sunde, and T. Vanden Hoek. 2008. Post-cardiac arrest syndrome: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, treatment, and prognostication. A consensus statement from the international liaison committee on resuscitation (American Heart Association, Australian and New Zealand Council on Resuscitation, European Resuscitation Council, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, InterAmerican Heart Foundation, Resuscitation Council of Asia, and the Resuscitation Council of Southern Africa); the American Heart Association Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee; the Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; the Council on Cardiopulmonary, Perioperative, and Critical Care; the Council on Clinical Cardiology; and the Stroke Council. Circulation 118(23):2452-2483.

Neumar, R. W., C. W. Otto, M. S. Link, S. L. Kronick, M. Shuster, C. W. Callaway, P. J. Kudenchuk, J. P. Ornato, B. McNally, S. M. Silvers, R. S. Passman, R. D. White, E. P. Hess, W. Tang, D. Davis, E. Sinz, and L. J. Morrison. 2010. Part 8: Adult advanced cardiovascular life support: 2010

American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation 122(18 Suppl 3):S729-S767.

Nichol, G., E. Thomas, C. W. Callaway, J. Hedges, J. L. Powell, T. P. Aufderheide, T. Rea, R. Lowe, T. Brown, J. Dreyer, D. Davis, A. Idris, and I. Stiell. 2008. Regional variation in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest incidence and outcome. Journal of the American Medical Association 300(12):1423-1431.

Peberdy, M. A., C. W. Callaway, R. W. Neumar, R. G. Geocadin, J. L. Zimmerman, M. Donnino, A. Gabrielli, S. M. Silvers, A. L. Zaritsky, R. Merchant, T. L. Vanden Hoek, and S. L. Kronick. 2010. Part 9: Post-cardiac arrest care: 2010 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation 122(18 Suppl 3):S768-S786.

Pierard, L. A. 2003. Assessing perfusion and function in acute myocardial infarction: How and when? Heart 89(70):701-703.

Pinchalk, M. E. 2010. Managing post cardiac arrest syndrome in the prehospital setting. Journal of Emergency Medical Services, online. http://www.jems.com/articles/2010/03/managing-post-cardiac-arrest-s.html (accessed June 15, 2015).

Resuscitation Academy. 2014. Strategies to improve survival from cardiac arrest: An evidence-based analysis. Seattle, WA: Resuscitation Academy. http://www.resuscitationacademy.com/downloads/RA-35-Strategies-to-ImproveCA-Survival.pdf (accessed June 8, 2015).

Roquin, A. 2006. Wilhelm His Jr. (1863-1934)—the man behind the bundle. Heart Rhythm 3(4):480-483.

Sasson, C., M. A. M. Rogers, J. Dahl, and A. L. Kellermann. 2010. Predictors of survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes 3(1):63-81.

Stecker, E. C., K. Reinier, E. Marijon, K. Nayayanan, C. Teodorescu, A. Uy-Evanado, K. Gunson, J. Jui, and S. S. Chugh. 2014. Public health burden of sudden cardiac death in the United States. Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology 7(2):212-217.

Stub, D., S. Bernard, S. J. Duffy, and D. M. Kaye. 2011. Post cardiac arrest syndrome: A review of therapeutic strategies. Circulation 123(13):1428-1435.

Taniguchi, D., A. Baernstein, and G. Nichol. 2012. Cardiac arrest: a public health perspective. Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America 30(1):1-12.

Travers, A. H., T. D. Rea, B. J. Bobrow, D. P. Edelson, R. A. Berg, M. R. Sayre, M. D. Berg, L. Chameides, R. E. O’Connor, and R. A. Swor. 2010. Part 4: CPR overview: 2010 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation 122(18 Suppl 3):S676-S684.

Vellano, K., A. Crouch, M. Rajdev, and B. McNally. 2015. Cardiac Arrest Registry to Enhance Survival (CARES) report on the public health burden of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Paper commissioned by the Committee on Treatment of Cardiac Arrest: Current Status and Future Directions. http://www.iom.edu/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2015/CARES.pdf (accessed

June 30, 2015).

Wright, D., C. James, A. K. Marsden, and A. F. Mackintosh. 1989. Defibrillation by ambulance staff who have had extended training. British Medical Journal 299(6691):96-97.