3

Conceptual Framework for Measuring the Impact of IPE

To date, the interprofessional education (IPE) literature has generally focused on formal and intentionally planned education and training programs (Freeth et al., 2005a,b; Nisbet et al., 2013). Most models of IPE have emphasized the characteristics of educational activities (e.g., type and duration of exposure) and learning outcomes. Some have addressed when IPE should occur (e.g., before or after licensure or certification) (Reeves et al., 2011). Fewer have explicitly considered where IPE occurs (e.g., classroom, clinical practice, or community settings) or what type of learning is most suited to a particular environment (D’Amour and Oandasan, 2004; Purden, 2005). Fewer still have examined patient, population, or system outcomes (Reeves et al., 2011, 2013).

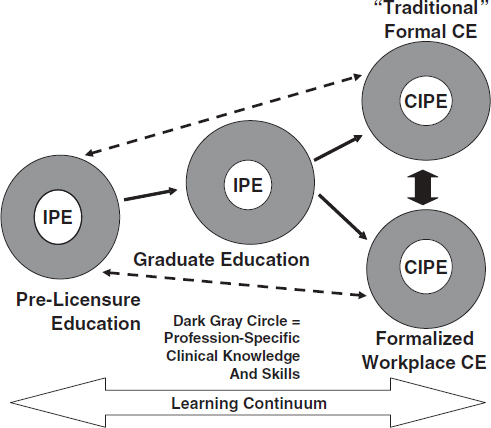

One model reviewed by the committee links a number of concepts related to IPE (see Figure 3-1) (Owen and Schmitt, 2013). This model builds on earlier thinking about a patient-centered approach to learning in the health professions and describes the intersections of IPE with basic education, graduate education, and continuing IPE; it also captures the understanding that point-of-care learning is a key component of lifelong learning (Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation, 2010). This broad definition of continuing education encompasses all learning (formal, informal, workplace, serendipitous) that enhances understanding and improves patient care (IOM, 2010; Nisbet et al., 2013). All of these elements are important in linking IPE to individual, population, and system outcomes.

This model became the basis for the committee’s consideration of more complex concepts than those generally used in designing IPE, understanding the role and utility of informal learning, and evaluating the outcomes of

FIGURE 3-1 An enhanced professional education model capturing essential concepts of interprofessional education.

NOTE: CE = continuing education; CIPE = continuing interprofessional education; IPE = interprofessional education.

SOURCE: Owen and Schmitt, 2013.

© 2013 The Alliance for Continuing Education in the Health Professions, the Society for Academic Continuing Medical Education, and the Council on Continuing Medical Education, Association for Hospital Medical Education. Published online in Wiley Online Library (wileyonlinelibrary.com). doi: 10.1002/chp.21173.

both formal and informal types of IPE. These concepts include the developmental stages of a professional’s career across the learning continuum, the incorporation of IPE into formal professional education across the developmental stages of a career, and the distinction between traditional formal continuing education (e.g., “update” models) and planned or serendipitous workplace learning (Lloyd et al., 2014; Nowlen, 1988). In addition, identifying the many activities that drive the need for effective evaluation of

collaborative patient-centered practice is viewed as important by a number of groups and individuals (Baldwin et al., 2010; IPEC, 2011; Schmitt et al., 2011). These activities include those focused on patient safety, quality improvement, and team-based care, as well as population health and cost considerations. To date, these concepts have not been explicitly delineated in a comprehensive, well-conceived model of IPE.

The importance of context and the role of informal learning have been acknowledged by many authors (Eraut, 2004; Freeth et al., 2005a). In the United States, for example, leaders of U.S. health care systems (Fihn et al., 2014; Jones and Lunge, 2014; Department of Vermont Health Access, 2014) describe efforts to create teams, engage new types of workers, implement quality improvement, and collect population data in their health systems. In these efforts, a variety of positive outcomes have resulted from the deployment of new interprofessional models of care that stress the value of workplace learning rather than formal educational activities. These large-scale system redesign efforts underline the importance of incorporating what has been called the untapped opportunity for learning and change within practice environments offered by workplace learning, individual and organizational performance improvement efforts, and patient safety programs (Nisbet et al., 2013). However, participants in such transformative initiatives do not always recognize informal activities as “learning” when those activities are part of everyday practice (Eraut, 2004). Moreover, education and health system leaders may fail to consider the possibility of using workplace learning at earlier stages of the education continuum.

The need for better alignment between education and health systems and across the various phases of the education continuum is reinforced

by large-scale transformative efforts. Without purposeful alignment, there is no feedback loop between education and practice or across the education continuum itself, and informal activities are not recognized or maximized as learning for everyone involved (students, health professionals, patients, families, and others). Too often students are directed to the classroom for their formal or foundational learning and only later to practice environments for short periods of time for application of those concepts, without a structured approach for learning in different environments.

“Too often students are directed to the classroom for their formal or foundational learning and only later to practice environments for short periods of time for application of those concepts, without a structured approach for learning in different environments.”

AN INTERPROFESSIONAL MODEL OF CONTINUOUS LEARNING

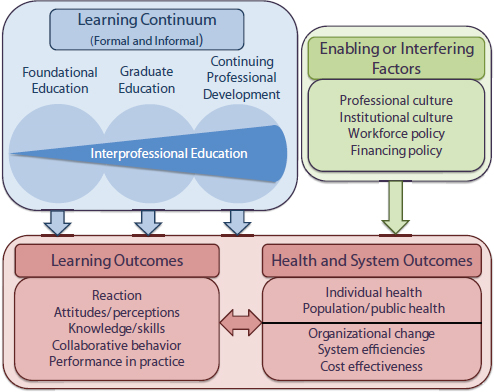

Following an extensive literature search for interprofessional models of learning, the committee determined that no existing models sufficiently incorporate all of the components needed to guide future studies. As a result, the committee developed a conceptual model that encompasses the education-to-practice continuum; a broad array of learning, health, and system outcomes; and major enabling and interfering factors. The committee puts forth this model with the understanding that it will need to be tested empirically and may need to be adapted to the particular settings in which it is applied. For example, educational structures and terminology differ considerably around the world, and the model may need to be modified to suit local or national conditions. However, the model’s overarching concepts—a learning continuum; learning-, health-, and system-related outcomes; and major enabling and interfering factors—would remain.

Enabling and interfering factors can impact outcomes and influence program evaluation directly or indirectly. Diverse payment structures and differences in professional and organizational cultures generate obstacles to effective interprofessional work and evaluation, while positive changes in workforce and financing policies may enable more effective collaboration and foster robust interprofessional evaluation.

An Interprofessional Conceptual Model for Evaluating Outcomes

The interprofessional learning continuum (IPLC) model shown in Figure 3-2 encompasses four interrelated components: a learning continuum; the outcomes of learning; individual and population health outcomes; system outcomes such as organizational changes, system efficiencies, and cost-effectiveness; and the major enabling and interfering factors that influence implementation and overall outcomes. It must be emphasized that successful application of this model is dependent on how well the interdependent education and health care systems, as described in the previous chapter, are aligned.

This model illustrates the developmental and ongoing nature of organized (formal) IPE and workplace (informal) learning that occur as health professionals prepare for practice and progress throughout their careers. IPE is an all-encompassing term for both formal and informal learning interventions across the education-to-practice continuum; however, the model also distinguishes among the different stages and types of professional development (foundational education, graduate education, and continuing professional development) (Reeves et al., 2011), as well as the ideally increasing percentage of overall IPE that occurs across these stages.

IPE activities generally comprise a small fraction of overall educational

FIGURE 3-2 The interprofessional learning continuum (IPLC) model.

NOTE: For this model, “graduate education” encompasses any advanced formal or supervised health professions training taking place between completion of foundational education and entry into unsupervised practice.

activities early in the learning continuum, when students are being immersed in the values and information of their chosen profession and when the formation of professional identity is critical (Buring et al., 2009; Wagner and Reeves, 2015). As learning shifts from the classroom to the practice or community environment, interprofessional work takes on greater significance. Learning becomes more relationship based and involves increasingly more complex interactions with others, including patients, families, and communities. While the model does not visually display the integral role these individuals and groups play, they increasingly are emerging as important members of the collaborative team.

IPE may be formal or informal at any point across the education-to-practice continuum, but informal learning (planned or serendipitous workplace learning) increases as students progress in their education and as graduates become fully licensed and certified practitioners. This is one

area in which local or national adaptation of the model would be necessary. Although the vast majority of health professionals are licensed and/or certified to practice, for example, there are emerging professions and individual country health workforce circumstances that would necessitate ongoing adjustments to the model. Some health professions are not licensed because licensure is not required for employment. Other emerging professions, such as integrated health and health coaching, have certification requirements, while health educators and social service workers have variable requirements depending on where the work is taking place (Healthcare Workforce Partnership of Western Mass, n.d.; SocialWorkLicensure.org, 2015; U.S. Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2014). By incorporating individual adaptations, the model allows for mapping the specific characteristics of an IPE intervention—timing, setting, and approach—to intermediate learning outcomes, and these, in turn, to specific types of health and system outcomes (Goldman et al., 2009; Oandasan and Reeves, 2005; Reeves et al., 2011). The model also takes into account the key factors (context, culture, and policy) that strongly influence, and in many cases confound, the design and analysis of any education intervention. Again, specific enabling and interfering factors will vary by setting and country. Specific health and system outcomes may also differ based on location and may include additional key indicators of health system performance, such as access to care and quality of care, possibly as they relate to the social determinants of health.

Furthermore, the model emphasizes that formal curricular interventions need to be designed intentionally to align specific interprofessional competencies with the professional’s developmental stage (Dow et al., 2014; Wagner and Reeves, 2015). Some refer to this as the “treatment and dose” of IPE, denoting what the intervention should be and how much of it is needed to produce a measurable learning outcome. Whether an intervention leads to a measurable health or system outcome will likely depend on the interplay of multiple factors with particular confounding influences (see Chapter 4 for more detailed discussion of this topic).

Education and Training Pathways

The required education and training pathways for health professionals vary greatly in length, complexity, and sequencing and can differ within professions around the world. But in many places and for most health professions, formal education is highly regulated by accreditation, while informal workplace learning is influenced by the practice environment, including certification and licensing standards that are specific to each profession. In the committee’s model, these concepts are incorporated in the three core developmental stages for health professionals: foundational

education, graduate education, and continuing professional development (both formal and informal).

Foundational education is the educational entry point to a profession. Learners are novices who are provided basic content foundational to their profession. With the introduction of core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice and new accreditation standards, IPE increasingly is being introduced at this early stage (CIHC, 2010; Curtin University, 2011; IPEC, 2011) and has been shown to have positive learning outcomes (Barr et al., 2005; Hawkes et al., 2013; Nisbet et al., 2008). Organized, formal IPE activities provide the basic underpinnings of collaborative competence. They generally are didactic or simulated or occur in highly supervised clinical environments.

For some professions, additional preparation is required in the form of graduate education or specialty training that is characterized by growing levels of independence. During this stage, supervisors or preceptors provide more complex situational learning experiences, while supervision for less complex situations decreases. Required competencies at this stage increasingly incorporate interprofessional practice skills such as practice-based learning and improvement and system-based practice (ACGME, 2013).

As health systems become more complex, there is increasing impetus to incorporate continuous improvement strategies so the system can evolve into a “learning organization” (deBurca, 2000; IOM, 2010). Accordingly, traditional approaches to continuing health professions education are moving beyond updating an individual professional’s knowledge or skills in an area of specialization toward competency development and performance improvement in practice, including interprofessional collaborative practice skills in integrated systems of care and in community settings (ABMS, 2015; Cervero and Gaines, 2014). Increasingly, models for health professions competence and performance link learning to organizational outcomes, including patient and population benefits (e.g., improved individual and community health and system efficiencies such as cost reduction) (Davis et al., 1999; Forsetlund et al., 2009; Moore et al., 2009; WHO, 2010).

This shift in focus is fueling renewed interest in the role of workplace learning as part of everyday practice in the continuing professional development stage of a health professional’s career (Gilman et al., 2014; Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation, 2010; Kitto et al., 2014; Marsick and Volpe, 1999; Regehr and Mylopoulos, 2008; Teunissen and Dornan, 2008). Nisbet and colleagues (2013, p. 469) propose a concept involving various types of workplace learning ranging from “the implicit unplanned learning . . . to more deliberative explicit focus on learning, where learning occurs through and is a central part of everyday work practice.” This notion encompasses formal continuing education activities for maintaining licensure or certification as well as interprofessional development activities for informal on-the-job learning.

Charting Expectations for Interprofessional Learning

Against the backdrop of educational stages that guide IPE programming and evaluation, the planning for learner competency and performance benefits from charting developmental expectations for mastery of competencies, including interprofessional skills linked to particular learning outcomes (Dow et al., 2014; Wagner and Reeves, 2015). Charting expectations for individual learners along the learning continuum provides markers for planning, implementing, and evaluating IPE activities at appropriate times and intervals that align with the educational path of other learners, and establishes the basis for a progression of learner assessments.

As used by some health professions, the concepts of expectations, competencies, and entrustable professional activities are outcome markers (e.g., knowledge, skills, attitudes, behavior) that can be achieved progressively along the continuum of a learner’s professional development (Mulder et al., 2010; ten Cate, 2013). These concepts take the learner from the earliest point of education and training through graduation and on to unsupervised practice. Assessment should be ongoing and feedback continuous to ensure that students achieve and demonstrate the competencies needed to move on to the next level of learning and development. Such an approach also can have value in resource-poor settings provided the educational design is adapted to address local health needs (Gruppen et al., 2012).

Levels of Learner Outcomes for Impact

Donald Kirkpatrick’s (1959, 1967, 1994) training evaluation model has frequently been referenced as a model for the evaluation of formal IPE interventions (e.g., Gillan et al., 2011; Grymonpre et al., 2010; Hammick et al., 2007; Robben et al., 2012; Theilen et al., 2013). Kirkpatrick’s four levels of outcomes—reaction, learning, behavior, and results—have been adapted by others (Weaver and Rosen, 2013), but the expansions of Barr et al. (2005) and Hammick et al. (2007) to include additional levels is increasingly being used in IPE (Mosley et al., 2012; Reeves et al., 2015) (see Table 3-1).

While the typology in Table 3-1 has provided a useful way of categorizing possible outcomes linked to IPE, the committee found it helpful to look back to Kirkpatrick’s original model and its intent in developing the new interprofessional learning model depicted in Figure 3-2. For Kirkpatrick (1959), as well as Miller (1990), the highest form of learning outcome is performance in practice on a daily basis in complex systems—a learned ability linked to formal training or the development of expertise over time. While the model retains its focus on most of the learning outcomes in Table 3-1 (reaction, changes in attitudes/perceptions, changes in collabora-

TABLE 3-1 Kirkpatrick’s Expanded Outcomes Typology

|

|

|

| Level 1: Learner’s reaction | Learners’ views on the learning experience and its interprofessional nature |

| Level 2a: Modification of attitudes/perceptions | Changes in reciprocal attitudes or perceptions between participant groups; changes in attitudes or perceptions regarding the value and/or use of team approaches to caring for a specific client group |

| Level 2b: Acquisition of knowledge/skills | Including knowledge and skills linked to interprofessional collaboration |

| Level 3: Behavioral change | Individuals’ transfer of interprofessional learning to their practice setting and their changed professional practice |

| Level 4a: Change in organizational practice | Wider changes in the organization and delivery of care |

| Level 4b: Benefits to patients, families, and communities | Improvements in health or well-being of patients, families, and communities |

|

|

|

SOURCE: Adapted from Reeves et al., 2015. For more information, visit http://tandfonline.com/loi/ijic.

tive behavior), it reinstates the outcome of performance in practice. In the model, performance is seen as an outcome beyond collaborative behavior, focused on working in complex systems using a complex set of skills to potentially impact changes in health care delivery (see Figure 3-2).

Use of the Kirkpatrick model has been questioned by some who argue that it was not originally designed to look at complex organizational or consumer change (Bates, 2004; Yardley and Dornan, 2012). In recognition of this complexity, the committee decided to differentiate (intermediate) learning outcomes from (final) health and system outcomes. In doing so, the committee incorporated a range of health outcomes (individual health, population/public health) and system outcomes (organizational change, systems efficiencies, cost-effectiveness) to show the possible (final) impact of IPE.

Having a comprehensive conceptual model provides a taxonomy and framework for discussion of the evidence linking IPE with learning, health, and system outcomes. Without such a model, evaluating the impact of IPE on the health of patients and populations and on health system structure and function is difficult and perhaps impossible.

The committee’s proposed model (see Figure 3-2) is the type of model needed to highlight desired system outcomes, such as those noted in Chap-

ter 1 (health, responsiveness, and fairness in financing), that can be attributed to IPE. While this particular model requires empirical testing, the further development and widespread adoption of this type of model could be driven by professional organizations with a stake in promoting, overseeing, and evaluating IPE. Its adoption would require the active participation of the broader education, regulatory, and research communities, as well as of health care delivery system leaders and policy makers.

In sum, adoption of a conceptual model of IPE could focus related research and evaluation on individual, population, and system outcomes that go beyond learning and testing of team function. By visualizing the entire IPE process, such a model illuminates the different environments where IPE occurs, as well as the importance of aligning education and practice, enabling more systemic and robust research. Wider adoption of a model of this type could bring greater uniformity to the design of IPE studies and allow consideration of the entire IPE process within its very complex environment.

Conclusion 2. Having a comprehensive conceptual model would greatly enhance the description and purpose of IPE interventions and their potential impact. Such a model would provide a consistent taxonomy and framework for strengthening the evidence base linking IPE with health and system outcomes.

ABMS (American Board of Medical Specialties). 2015. Promoting CPD through MOC. http://www.abms.org/initiatives/committing-to-physician-quality-improvement/promoting-cpd-through-moc (accessed March 17, 2015).

ACGME (Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education). 2013. ACGME program requirements for graduate medical education in internal medicine. https://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PFAssets/2013-PR-FAQ-PIF/140_internal_medicine_07012013.pdf (accessed December 29, 2014).

Baldwin, M., J. Hashima, J. M. Guise, W. T. Gregory, A. Edelman, and S. Segel. 2010. Patient-centered collaborative care: The impact of a new approach to postpartum rounds on residents’ perception of their work environment. Journal of Graduate Medical Education 2(1):62-66.

Barr, H., I. Koppel, S. Reeves, M. Hammick, and D. Freeth. 2005. Effective interprofessional education: Argument, assumption, and evidence. Oxford and Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

Bates, R. 2004. A critical analysis of evaluation practice: The Kirkpatrick model and the principle of beneficence. Evaluation and Program Planning 27:341-347.

Buring, S. M., A. Bhushan, A. Broeseker, S. Conway, W. Duncan-Hewitt, L. Hansen, and S. Westberg. 2009. Interprofessional education: Definitions, student competencies, and guidelines for implementation. The American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 73(4):59.

Cervero, R. M., and J. K. Gaines. 2014. Effectiveness of continuing medical education: Updated syntheses of systematic reviews. Chicago, IL: Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education.

CIHC (Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative). 2010. A national interprofessional competency framework. Vancouver, BC: CIHC.

Curtin University. 2011. Curtin interprofessional capability framework, Sydney, Australia. http://healthsciences.curtin.edu.au/local/docs/IP_Capability_Framework_booklet.pdf (accessed December 29, 2014).

D’Amour, D., and I. Oandasan. 2004. IECPCP framework. In Interdisciplinary Education for Collaborative, PatientCentred Practice: Research and Findings Report, edited by I. Oandasan, D. D’Amour, M. Zwarenstein, K. Barker, M. Purden, M.-D. Beaulieu, S. Reeves, L. Nasmith, C. Bosco, L. Ginsburg, and D. Tregunno. Ottawa, Canada: Health Canada. http://www.ferasi.umontreal.ca/eng/07_info/IECPCP_Final_Report.pdf (accessed March 17, 2015).

Davis, D., M. O’Brien, N. Freemantle, F. M. Wolf, P. Mazmanian, and A. Taylor-Vaisey. 1999. Impact of formal continuing medical education: Do conferences, workshops, rounds, and other traditional continuing education activities change physician behavior or health care outcomes? Journal of the American Medical Association 282(9):867-874.

deBurca, S. 2000. The learning health care organization. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 12(6):457-458.

Department of Vermont Health Access. 2014. Vermont blueprint for health: 2013 annual report (January 30, 2014). Williston, VT: Department of Vermont Health Access.

Dow, A., D. Diaz Granados, P. E. Mazmanian, and S. M. Retchin. 2014. An exploratory study of an assessment tool derived from the competencies of the interprofessional education collaborative. Journal of Interprofessional Care 28(4):299-304.

Eraut, M. 2004. Informal learning in the workplace. Studies in Continuing Education 26(2):247-273.

Fihn, S. D., J. Francis, C. Clancy, C. Nielson, K. Nelson, J. Rumsfeld, T. Cullen, J. Bates, and G. L. Graham. 2014. Insights from advanced analytics at the Veterans Health Administration. Health Affairs (Millwood) 33(7):1203-1211.

Forsetlund, L., A. Bjorndal, A. Rashidian, G. Jamtvedt, M. A. O’Brien, F. Wolf, D. Davis, J. Odgaard-Jensen, and A. D. Oxman. 2009. Continuing education meetings and workshops: Effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2:Cd003030.

Freeth, D., M. Hammick, S. Reeves, I. Koppel, and H. Barr. 2005a. Effective interprofessional education: Development, delivery and evaluation. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, Ltd.

Freeth, D., S. Reeves, I. Koppel, M. Hammick, and H. Barr. 2005b. Evaluating interprofessional education: A selfhelp guide. London: Higher Education Academy Health Sciences and Practice Network.

Gillan, C., E. Lovrics, E. Halpern, D. Wiljer, and N. Harnett. 2011. The evaluation of learner outcomes in interprofessional continuing education: A literature review and an analysis of survey instruments. Medical Teacher 33(9):e461-e470.

Gilman, S. C., D. A. Chokshi, J. L. Bowen, K. W. Rugen, and M. Cox. 2014. Connecting the dots: Interprofessional health education and delivery system redesign at the veterans health administration. Academic Medicine 89(8):1113-1116.

Goldman, J., M. Zwarenstein, O. Bhattacharyya, and S. Reeves. 2009. Improving the clarity of the interprofessional field: Implications for research and continuing interprofessional education. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions 29(3):151-156.

Gruppen, L. D., R. S. Mangrulkar, and J. C. Kolars. 2012. The promise of competency-based education in the health professions for improving global health. Human Resources for Health 10(1):43.

Grymonpre, R., C. van Ineveld, M. Nelson, F. Jensen, A. De Jaeger, T. Sullivan, L. Weinberg, J. Swinamer, and A. Booth. 2010. See it–do it–learn it: Learning interprofessional collaboration in the clinical context. Journal of Research in Interprofessional Practice and Education 1(2):127-144.

Hammick, M., D. Freeth, I. Koppel, S. Reeves, and H. Barr. 2007. A best evidence systematic review of interprofessional education: BEME guide no. 9. Medical Teacher 29(8):735-751.

Hawkes, G., I. Nunney, and S. Lindqvist. 2013. Caring for attitudes as a means of caring for patients improving medical, pharmacy and nursing student’s attitudes to each other’s professions by engaging them in interprofessional learning. Medical Teacher 35(7):e1302-e1308.

Healthcare Workforce Partnership of Western Mass. n.d. Healthcare workforce partnership of Western Mass website: Health educators. http://westernmasshealthcareers.org/local-careers/office-research/health-educators (accessed January 27, 2015).

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2010. Redesigning continuing education in the health professions. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IPEC (Interprofessional Education Collaborative). 2011. Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: Report of an expert panel. Washington, DC: IPEC.

Jones, C., and R. Lunge. 2014. Blueprint for health report: Medical homes, teams, and community health systems. Montpelier, VT: State of Vermont Agency of Administration Health Care Reform.

Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation. 2010. Lifelong learning in medicine and nursing: Final conference report. New York: Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation.

Kirkpatrick, D. L. 1959. Techniques for evaluating training programs. Journal of American Society of Training Directors 13(11):3-9.

Kirkpatrick, D. L. 1967. Evaluation of training. In Training and development handbook, edited by R. L. Craig and L. R. Bittel. New York: McGraw-Hill. Pp. 87-112.

Kirkpatrick, D. L. 1994. Evaluating training programs: The four levels. 1st ed. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc.

Kitto, S., J. Goldman, M. H. Schmitt, and C. A. Olson. 2014. Examining the intersections between continuing education, interprofessional education and workplace learning. Journal of Interprofessional Care 28(3):183-185.

Lloyd, B., D. Pfeiffer, J. Dominish, G. Heading, D. Schmidt, and A. McCluskey. 2014. The New South Wales Allied Health Workplace Learning Study: Barriers and enablers to learning in the workplace. BMC Health Services Research 14:134.

Marsick, V. J., and M. Volpe. 1999. The nature and need for informal learning. Advances in Developing Human Resources 1(3):1-9.

Miller, G. E. 1990. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Academic Medicine 9(Suppl.):S63-S67.

Moore, D. E., Jr., J. S. Green, and H. A. Gallis. 2009. Achieving desired results and improved outcomes: Integrating planning and assessment throughout learning activities. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions 29(1):1-15.

Mosley, C., C. Dewhurst, S. Molloy, and B. N. Shaw. 2012. What is the impact of structured resuscitation training on healthcare practitioners, their clients and the wider service? A BEME systematic review: BEME guide no. 20. Medical Teacher 34(6):e349-e385.

Mulder, H., O. ten Cate, R. Daalder, and J. Berkvens. 2010. Building a competency-based workplace curriculum around entrustable professional activities: The case of physician assistant training. Medical Teacher 32(10):e453-e459.

Nisbet, G., G. D. Hendry, G. Rolls, and M. J. Field. 2008. Interprofessional learning for prequalification health care students: An outcomes-based evaluation. Journal of Interprofessional Care 22(1):57-68.

Nisbet, G., M. Lincoln, and S. Dunn. 2013. Informal interprofessional learning: An untapped opportunity for learning and change within the workplace. Journal of Interprofessional Care 27(6):469-475.

Nowlen, P. M. 1988. A new approach to continuing education for business and the professions. New York: Macmillan.

Oandasan, I., and S. Reeves. 2005. Key elements for interprofessional education. Part 2: Factors, processes and outcomes. Journal of Interprofessional Care 19(Suppl. 1):39-48.

Owen, J., and M. Schmitt. 2013. Integrating interprofessional education into continuing education: A planning process for continuing interprofessional education programs. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions 33(2):109-117.

Purden, M. 2005. Cultural considerations in interprofessional education and practice. Journal of Interprofessional Care 19(Suppl. 1):224-234.

Reeves, S., J. Goldman, J. Gilbert, J. Tepper, I. Silver, E. Suter, and M. Zwarenstein. 2011. A scoping review to improve conceptual clarity of interprofessional interventions. Journal of Interprofessional Care 25(3):167-174.

Reeves, S., L. Perrier, J. Goldman, D. Freeth, and M. Zwarenstein. 2013. Interprofessional education: Effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes (update). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 3:CD002213.

Reeves, S., S. Boet, B. Zierler, and S. Kitto. 2015. Interprofessional education and practice guide no. 3: Evaluating interprofessional education. Journal of Interprofessional Care 29(4):305-312.

Regehr, G., and M. Mylopoulos. 2008. Maintaining competence in the field: Learning about practice, through practice, in practice. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions 28(Suppl. 1):S19-S23.

Robben, S., M. Perry, L. van Nieuwenhuijzen, T. van Achterberg, M. O. Rikkert, H. Schers, M. Heinen, and R. Melis. 2012. Impact of interprofessional education on collaboration attitudes, skills, and behavior among primary care professionals. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions 32(3):196-204.

Schmitt, M., A. Blue, C. A. Aschenbrener, and T. R. Viggiano. 2011. Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: Reforming health care by transforming health professionals’ education. Academic Medicine 86(11):1351.

SocialWorkLicensure.org. 2015. Social work licensure requirements. http://www.socialworklicensure.org (accessed January 27, 2015).

ten Cate, O. 2013. Nuts and bolts of entrustable professional activities. Journal of Graduate Medical Education 5(1):157-158.

Teunissen, P. W., and T. Dornan. 2008. Lifelong learning at work. BMJ 336(7645):667-669.

Theilen, U., P. Leonard, P. Jones, R. Ardill, J. Weitz, D. Agrawal, and D. Simpson. 2013. Regular in situ simulation training of paediatric medical emergency team improves hospital response to deteriorating patients. Resuscitation 84(2):218-222.

U.S. Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2014. How to Become a Health Educator or Community Health Worker. http://www.bls.gov/ooh/community-and-social-service/health-educators.htm#tab-4 (accessed June 5, 2015).

Wagner, S., and S. Reeves. 2015. Milestones and entrustable professional activities: The key to practically translating competencies for interprofessional education? Journal of Interprofessional Care 1-2.

Weaver, S. J., and M. A. Rosen. 2013. Team-training in health care: Brief update review. In Making health care safer II: An updated critical analysis of the evidence for patient safety practices (evidence reports/technology assessments, no. 211). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Pp. 472-479.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2010. Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. http://www.who.int/hrh/resources/framework_action/en/index.html (accessed March 4, 2013).

Yardley, S., and T. Dornan. 2012. Kirkpatrick’s levels and education “evidence.” Medical Education 46(1):97-106.