5

Improving Research Methodologies

Previous chapters have identified three major barriers to the maturation of interprofessional education (IPE) and collaborative practice: lack of alignment between education and practice (see Chapter 2), lack of a standardized model of IPE across the education continuum (see Chapter 3), and significant gaps in the evidence linking IPE to collaborative practice and patient outcomes (see Chapter 4). This chapter presents the committee’s analysis of how best to improve the evidence base and move the field forward.

ENGAGING TEAMS FOR EVALUATION OF IPE

Collaboration is at the heart of effective IPE and interprofessional practice. Likewise, researchers and educators working effectively together in teams could provide a solid foundation on which to build IPE evaluation. As noted in Chapter 4, evaluation of IPE interventions with multiple patient, population, and system outcomes is a complex undertaking. Individuals working alone rarely have the broad evaluation expertise and resources to develop or implement the protocols required to address the key questions in the field (Adams and Dickinson, 2010; ANCC, 2014; Ridde et al., 2009; Turnbull et al., 1998). In the absence of robust research designs, there is a risk that future studies testing the impact of IPE on individual, population, and system outcomes will continue to be unknowingly biased, underpowered to measure true differences, and not generalizable across different systems and types and levels of learners. One possible root cause of poorly designed studies may be that the studies are led by educators who have limited time to devote to research or who may not have formal

research training. Therefore, teams of individuals with complementary expertise would be far preferable and have greater impact on measuring the effectiveness of IPE. An IPE evaluation team might include an educational evaluator, a health services researcher, and an economist, in addition to educators and others engaged in IPE.

EMPLOYING A MIXED-METHODS APPROACH

Understanding the full complexity of IPE and the education and health care delivery systems within which it resides is critical for designing studies to measure the impact of IPE on individual, population, and system outcomes. Given this complexity, the use of a single research design or methodology alone may generate findings that fail to provide sufficient detail and context to be informative. IPE research would benefit from the adoption of a mixed-methods approach that combines quantitative and qualitative data to yield insight into both the “what” and “how” of an IPE intervention and its outcomes. Such an approach has been shown to be particularly useful for exploring the perceptions of both individuals and society regarding issues of quality of care and patient safety (Curry et al., 2009; De Lisle, 2011). Creswell and Plano Clark (2007) describe the approach as “a research design with philosophical assumptions as well as methods of inquiry”1 (p. 5).

The iMpact on practice, oUtcomes and cost of New ROles for health profeSsionals (MUNROS) project (see Box 5-1) is an example of a longitudinal, mixed-methods approach for evaluating the impact of health professional teams organized to deliver services in a more cost-effective manner following the recent financial crisis experienced by most European countries.

Comparative Effectiveness Research

Comparative effectiveness research2 is one approach for combining different study methods used in complex environments such as health

____________

1 “As a methodology, it involves philosophical assumptions that guide the direction of the collection and analysis of data and the mixture of qualitative and quantitative approaches in many phases in the research process. As a method, it focuses on collecting, analyzing, and mixing both quantitative and qualitative data in a single study or series of studies. Its central premise is that the use of quantitative and qualitative approaches in combination provides a better understanding of research problems than either approach alone” (Creswell and Plano Clark, 2007, p. 5).

2 The Institute of Medicine (IOM) Committee on Comparative Effectiveness Research Prioritization defines comparative effectiveness research as “the generation and synthesis of evidence that compares the benefits and harms of alternative methods to prevent, diagnose, treat, and monitor a clinical condition or to improve the delivery of care” (IOM, 2010, p. 41).

BOX 5-1

The iMpact on practice, oUtcomes and cost of New ROles for health profeSsionals (MUNROS) Project

With support from the European Commission, the MUNROS project is a 4-year systematic evaluation of the impact of changing health professional roles and team-based delivery of health services (MUNROS, 2015). Universities from nine different European countries make up the consortium designing the cross-sectional and multilevel study. They employ a mixed-methods approach to evaluate the impact of the newly defined professional roles on clinical practice, patient outcomes, health systems, and costs in a range of different health care settings within the European Union and Associate Countries (Czech Republic, England, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Scotland, and Turkey).

The study is divided into 10 research processes as follows:

1 and 2: Develop an evaluation framework for mapping the skills and competencies of the health workforce, which will be used in the economic evaluation of the data.

3: Collect information that can aid in the development of questionnaires for health care professionals, managers, and patients. This is done using case study methodology to identify the contributions of the new health professionals.

4: Develop the questionnaires.

5 and 6: Implement the surveys. The survey of the health professionals is aimed at determining the impact of new professional roles on clinical practice and the organization of care; the survey of patients assesses the impact of the new professionals on patient satisfaction and personal experiences.

7: Collect secondary data on hospital processes, productivity, and health outcomes. The data will be helpful in assessing the impact of the new professionals.

8: Conduct an economic evaluation that includes costs and benefits of the new professional roles and identifies incentives for increasing their impact.

9: Based on the collected data, provide examples of optimal models of integration of care and the associated costs, and offer detail on how the new professional roles might be carried out to improve the integration of care.

10: Build a workforce planning model for all levels of care that reflects the dynamic interaction between the workforce skill mix and the quality and cost of care for patients.

Following analysis of the data on the costs of these newly organized health care teams, European and country-level stakeholders will be engaged to maximize the impact of the results at the policy and practitioner levels.

care that, according to a previous Institute of Medicine (IOM) committee, can “assist consumers, clinicians, purchasers, and policy makers to make informed decisions that will improve health care at both the individual and population levels” (IOM, 2010, p. 41; Sox and Goodman, 2012). An important element of comparative effectiveness research is determining the benefit an intervention produces in routine clinical practice, rather than in a carefully controlled setting. Through such studies, it may also be possible to evaluate the financial justification for IPE—an important part of any return-on-investment analysis, as discussed below.

Return on Investment

Demonstrating financial return on investment is part of comparative effectiveness research and a key element for the sustainability of all health professions education, including IPE (Bicknell et al., 2001; IOM, 2014; Starck, 2005; Walsh et al., 2014). Proof-of-concept studies demonstrating the impact of IPE on individual, population, and systems outcomes, including a return on investment, will likely be necessary if there are to be greater financial investments in IPE. This is where alignment between the education and health care delivery systems becomes critical so that the academic partner (creating the IPE intervention/activity) and care delivery system partner (hosting the intervention and showcasing the outcomes) are working together. High-level stakeholders, such as policy makers, regulatory agencies, accrediting bodies, and professional organizations that oversee or encourage collaborative practice, will need to contribute as well. These stakeholders might, for example, provide incentives for programs and organizations to better align IPE with collaborative practice so the potential long-term savings in health care costs can be evaluated.

“Demonstrating financial return on investment is part of comparative effectiveness research and a key element for the sustainability of all health professions education, including IPE.”

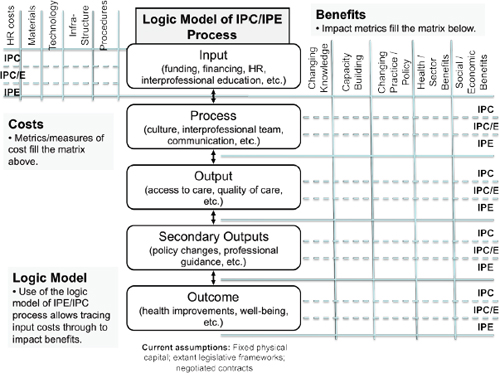

The framework developed by the Canadian Institute on Governance (see Figure 5-1) and described by Nason (2011) and Suter (2014) was created to facilitate analysis of the return on investment of specific IPE interventions or collaborative care approaches. This framework includes a logic model for tracing input costs through to benefits, and although as yet untested, may prove useful as a framework for investigating the return on investment of IPE.

Based on the evidence and the committee’s expert opinion, it is apparent that using either quantitative or qualitative methods alone will limit the ability of investigators in both developed and developing countries to

FIGURE 5-1 A framework for analysis of return on investment of IPE interventions or collaborative care approaches.

NOTE: HR = human resources; IPC = interprofessional collaboration; IPE = interprofessional education.

SOURCE: Nason, 2011. Used with kind permission of the Institute on Governance and the Health Education Task Force.

produce high-quality studies linking IPE with health and system outcomes. The committee therefore makes the following recommendation:

Recommendation 2: Health professions educators and academic and health system leaders should adopt mixed-methods study designs for evaluating the impact of interprofessional education (IPE) on health and system outcomes. When possible, such studies should include an economic analysis and be carried out by teams of experts that include educational evaluators, health services researchers, and economists, along with educators and others engaged in IPE.

Once best practices in the design of IPE studies have been established, disseminating them widely through detailed reporting or publishing can strengthen the evidence base and help guide future studies in building on a

foundation of high-quality empirical work linking IPE to outcomes. These studies could include those focused on eliciting in-depth patient, family, and caregiver experiences of collaborative practice. Sharing best practices in IPE study design is an important way of improving the quality of studies themselves. Work currently under way on developing methods for evaluating the impact of IPE—such as that of the U.S. National Center for Interprofessional Practice and Education—could inform the work of those with fewer resources provided that the concepts and methodologies employed are used appropriately and adapted to the local context in which they are applied. Box 5-2 offers suggestions for a potential program for evaluative research connecting IPE to health and system outcomes.

More robust evaluation designs and methods could increase the number of high-quality IPE studies. The use of a mixed-methods approach would be

BOX 5-2

Connecting IPE to Health and System Outcomes: A Potential Program of Research

A. Identify and Secure Key Program Elements

- Ensure that education and health system leaders are supportive of the program and that sufficient resources will be available to accomplish and sustain the work (see Chapter 2). Without these elements in place or clearly identified, the feasibility, scope, and substance of the program will be open to question.

- Assemble an interprofessional evaluation team as early as possible. The design of the evaluation plan should proceed concurrently with the development of the education interventions.

- Select and be guided by a conceptual model that provides a comprehensive framework encompassing the education continuum; learning, health, and system outcomes; and confounding factors (see Chapter 3).

- Although classroom and simulation activities are valuable early in the learning continuum, and their evaluation can be informative, the clinical or community workplace is the preferred site for evaluating the effects of IPE on health and system outcomes.

- Identify workplace learning sites (practice environments) in which interprofessional activities are built on sound theoretical underpinnings and add value to the overall work of the site. Connecting students with team-based quality improvement and patient safety activities may be especially valuable.

- Learning teams should include the appropriate professions and levels of learners for the clinical tasks required of them and should be adequately prepared for the workplace learning opportunities provided.

particularly useful. Both “big data” and smaller data sources could prove useful if studies are well designed and the outcomes well delineated. It will be important to identify and evaluate collective (i.e., team, group, network) as well as individual outcomes.

In addition and where applicable, the use of randomized and longitudinal designs that are adequately powered could demonstrate differences between groups or changes over time. Using the realist evaluation approach could provide in-depth understanding of IPE interventions beyond outcomes by illuminating how the outcomes were produced, by whom, under what conditions, and in what settings (Pawson and Tilley, 1997). This information could be particularly useful for maximizing resource allocation, which might also be informed through comparative effectiveness research.

Organizing studies to elicit in-depth patient, family, and caregiver experiences related to their involvement in IPE could promote alignment between education and practice to impact person-centered outcomes. A similar design could be used in studying the impact of IPE on specific com-

- Faculty, preceptor, and staff development generally is necessary to ensure positive experiences and exposure of learners to applied interprofessional activities.

- Ensure that the IPE interventions being evaluated are competency-based and linked to team behaviors that support interprofessional collaborative practice. If this is not the case, preliminary studies should be conducted to establish these relationships.

B. Select a Robust Evaluation Design

- Select the most robust evaluation methods for the health and system outcomes being addressed. The particular evaluation methods will depend on the specific question(s) being examined, but give serious consideration to using both qualitative and quantitative methods (as described in Table 4-1). Using a single data set can limit the level of detail a study is able to produce. A mixed-methods approach can generate more comprehensive information about an IPE intervention/activity.

- Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are still considered the “gold standard” but may not always be feasible in practice settings because of the relatively small numbers of subjects, as well as difficulties in assigning learners to control and intervention groups. Controlled before-and-after studies have similar limitations.

- In some cases, cluster randomized designs (involving groups of teams or individual practices) can be used to overcome difficulties in assigning subjects to control and intervention groups, but intermixing may still be a problem.

- Although commonly employed in education research, uncontrolled before-and-after studies generally do not have the power or precision to link education interventions to health and systems outcomes.

munity and public health outcomes to build the evidence base in this area. Studying systems in which best practices in IPE cross the continuum from education to health or health care (e.g., the Veterans Health Administration and countries where education and health ministries work together) could illuminate a path for greater alignment between systems in different settings.

Disseminating best practices through detailed reporting or publishing could also strengthen the evidence base and help guide future research. Both formal publication and informal channels such as blogs and newsletters can be powerful platforms for getting messages to researchers. The use of tools such as Replicability of Interprofessional Education (RIPE) could facilitate greater replicability of IPE studies through more structured and standardized reporting (Abu-Rish et al., 2012). Journal editors might require researchers to publish supplemental details on their IPE interventions and outcomes online, and well-designed and well-executed studies could be used as exemplars on websites. Given time and resource constraints, having access to robust study designs and better descriptions for replicability could greatly assist faculty in meeting IPE accreditation standards. For standardization, research teams could be encouraged to draw on the modified Kirkpatrick typology (Barr et al., 2005) and available toolkits when designing evaluations of IPE interventions. Another resource is the work of Reeves and colleagues (2015), who provide guidance on how to design and implement more robust studies of IPE.

In recognition of the importance of placing individual and population health at the center of health professions education, the committee has offered three major conclusions: (1) on the need for better alignment of education and health care delivery systems, (2) the need for a standardized model of IPE, and (3) the need for a stronger evidence base linking IPE to health and system outcomes. The committee also has put forth two recommendations for consideration by research teams: (1) the development of measures of collaborative performance that are effective across a broad range of learning environments; and (2) the adoption of a mixed-methods approach when evaluating IPE outcomes.

The committee recognizes “the importance of placing individual and population health at the center of health professions education.”

Collectively, these conclusions and recommendations are aimed at elevating the profile of IPE in a rapidly changing world. The committee hopes this report will shed additional light on the value of collaboration among educators, researchers, practitioners, patients, families, and communities, as well as all those who come together in working to improve lives through treatment and palliation, disease prevention, and wellness interventions. Only through

the publication of rigorously designed studies can the potential impact of IPE on health and health care be fully realized.

Abu-Rish, E., S. Kim, L. Choe, L. Varpio, E. Malik, A. A. White, K. Craddick, K. Blondon, L. Robins, P. Nagasawa, A. Thigpen, L. L. Chen, J. Rich, and B. Zierler. 2012. Current trends in interprofessional education of health sciences students: A literature review. Journal of Interprofessional Care 26(6):444-451.

Adams, J., and P. Dickinson. 2010. Evaluation training to build capability in the community and public health workforce. American Journal of Evaluation 31(3):421-433.

ANCC (American Nurses Credentialing Center). 2014. The importance of evaluating the impact of continuing nursing education on outcomes: Professional nursing practice and patient care. Silver Spring, MD: ANCC’s Commission on Accreditation.

Barr, H., I. Koppel, S. Reeves, M. Hammick, and D. Freeth. 2005. Effective interprofessional education: Argument, assumption, and evidence. Oxford and Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

Bicknell, W. J., A. C. Beggs, and P. V. Tham. 2001. Determining the full costs of medical education in Thai Binh, Vietnam: A generalizable model. Health Policy and Planning 16(4):412-420.

Creswell, J. W., and V. L. Plano Clark. 2007. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Curry, L. A., I. M. Nembhard, and E. H. Bradley. 2009. Qualitative and mixed methods provide unique contributions to outcomes research. Circulation 119(10):1442-1452.

De Lisle, J. 2011. The benefits and challenges of mixing methods and methodologies: Lessons learnt from implementing qualitatively led mixed methods research designs in Trinidad and Tobago. Caribbean Curriculum 18:87-120.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2010. Redesigning continuing education in the health professions. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2014. Graduate medical education that meets the nation’s health needs. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

MUNROS (iMpact on practice, oUtcomes and cost of New ROles for health profeSsionals. 2015. Health care reform: The impact on practice, outcomes and costs of new roles for health professionals. https://www.abdn.ac.uk/munros (accessed March 17, 2015).

Nason, E. 2011. The “ROI” in “team”: Return on investment analysis framework, indicators and data for IPC and IPE. Ontario, Canada: Institute on Governance.

Pawson, R., and N. Tilley. 1997. Realistic evaluation. London: Sage Publications.

Reeves, S., S. Boet, B. Zierler, and S. Kitto. 2015. Interprofessional education and practice guide no. 3: Evaluating interprofessional education. Journal of Interprofessional Care 29(4):305-312.

Ridde, V., P. Fournier, B. Banza, C. Tourigny, and D. Ouedraogo. 2009. Programme evaluation training for health professionals in Francophone Africa: Process, competence acquisition and use. Human Resources for Health 7:3.

Sox, H. C., and S. N. Goodman. 2012. The methods of comparative effectiveness research. Annual Review of Public Health 33:425-445.

Starck, P. L. 2005. The cost of doing business in nursing education. Journal of Professional Nursing 21(3):183-190.

Suter, E. 2014. Presentation at open session for measuring the impact of interprofessional education (IPE) on collaborative practice and patient outcomes: A consensus study. http://www.iom.edu/Activities/Global/MeasuringtheImpactofInterprofessionalEducation/2014OCT-07.aspx (accessed December 8, 2014).

Turnbull, J., J. Gray, and J. MacFadyen. 1998. Improving in-training evaluation programs. Journal of General Internal Medicine 13(5):317-323.

Walsh, K., S. Reeves, and S. Maloney. 2014. Exploring issues of cost and value in professional and interprofessional education. Journal of Interprofessional Care 28(6):493-494.