6

Taking the Census II: The Uses of Sampling and Administrative Records

The charge to the panel called for assessment of the uses of sampling and administrative records to improve the cost-effectiveness of the decennial census. Recent census methodology has incorporated both of these techniques into one or more aspects of census operations, but there may well be room to extend their use. This chapter evaluates a range of uses of sampling for obtaining the count and characteristics and also considers the joint use of administrative records and sampling to improve the quality of certain census items.

Sampling has been employed since the 1940 census to obtain additional useful data without the burden and expense of asking all questions of the entire population. Sampling has also been used as part of census operations for purposes of quality control and has been extensively used in postcensal programs of coverage and content evaluation. Recently, it has been suggested that sampling could prove cost-effective in helping to fulfill the basic purpose of the decennial census—obtaining the population count for the nation, states, and small areas.

The panel examined the merits of the following potential uses of sampling for the count: (1) taking a sample census, (2) conducting follow-up of a sample of households that do not return their questionnaires, and (3) implementing coverage improvement programs for hard-to-count areas and population groups on a sample basis. The panel also reviewed issues in sampling for content, including criteria for deciding when to include ques-

tions on the short form administered to 100 percent of the population and when to include questions on one or more long forms administered to a sample. The panel also considered the merits of a follow-on sample survey to obtain additional information. Finally, the panel reviewed the uses of sampling in conjunction with administrative records for verification and improvement of the quality of subject items collected in the census. Sampling is also discussed in Chapter 8 in the context of coverage evaluation methods. Because we believe that the use of sampling in an operational context for quality control is a well-understood application, we do not comment on these uses of sampling in the census, despite the great importance of careful control of all aspects of census procedures.

The panel reviewed two papers prepared by staff of the Census Bureau outlining proposed research on uses of sampling for the head count and content in 1990. The paper by Miskura et al., “Uses of Sampling for the Census Count” (1984), describes four applications of sampling for the decennial census and proposes research projects for each type of use: (1) obtaining the census count on a sample basis, (2) using sampling for follow-up of unit nonresponse in the census, (3) using sampling for coverage improvement operations, and (4) using sampling for verification and possible correction of specific subject items during the census.

A package of papers prepared in summer 1984, “Interim Census Manager Reports on 1986 Pretest Objectives” (Johnson, 1984), describes proposals for the round of 1990 census pretests to be conducted in spring 1986. Proposed tests that involved the use of sampling for the count or content included: (1) a split panel test of sampling for unit nonresponse follow-up, (2) simulating the use of sampling for one of the coverage improvement programs—the Vacant/Delete Check, and (3) testing a general-purpose follow-on survey of 1-2 percent of short-form recipients conducted a few months after completion of the census enumeration. However, the Census Bureau has dropped the first two projects listed from the current 1986 pretest plans (see Bureau of the Census, 1985b).

Any evaluation of the costs and benefits of a particular sampling procedure must endeavor to assess the gains or losses on several dimensions compared with an alternate procedure. The comparison procedure could be a complete enumeration or another variant of sampling, for example, the use of a larger or smaller sampling fraction or a different sample selection procedure. Criteria considered by the panel include:

- Accuracy of the information obtained. Errors in surveys traditionally are thought of as having two components: sampling and nonsampling. Sampling error is inherent in sample surveys and necessarily increases the random variation of observed values from true values, compared with a complete enumeration. Nonsampling

-

error may arise from question wording, field techniques, or many other sources and can occur both in samples and in complete enumerations. It is possible that a well-designed and executed sampling operation can reduce nonsampling error compared with a complete enumeration because the staff may be better trained and procedures more uniformly applied. It is, of course, also possible for the sample survey design to introduce nonsampling error. Furthermore, certain components of nonsampling error appear as variances that decrease with increasing sample size.

- Cost. In the context of the decennial census, which cost over $1 billion in 1980, the cost impact of any proposed methodology is an important consideration. Sampling is usually expected to reduce costs compared with a complete count, and small samples are expected to cost less than large samples; however, this is not always the case. The use of sampling introduces costs associated with sample design, selection of the sample, quality control of the sampling operation, processing of the data to estimate universe totals, and assessment of the quality of the information obtained.

- Timing. The length of time required for an operation is important in the census context. Shortening the time between Census Day and completion of the enumeration has positive implications for cost savings, for earlier availability of the data, and for improved accuracy of the numbers. (For example, the shorter the field operation, the less opportunity there is to miscount movers.) Sampling may have the benefit of reducing the calendar time required to complete the census field work.

- Feasibility. The enormous scale of census operations places a high premium on the feasibility of proposed methodologies in the field. Sampling may have drawbacks on this dimension if it proves more difficult to implement a sample operation than to conduct a complete enumeration. Because the census is a massive undertaking conducted within a brief time span only once every 10 years, there are not the opportunities to refine sampling procedures and to train field staff afforded in a continuing sample survey.

- Respondent burden. Sampling reduces the aggregate time the public must spend filling out questionnaires as well as the survey costs. Since the decennial census is conducted only once every 10 years, the panel does not view reducing respondent burden as an important argument for increased use of sampling to obtain the basic census counts. However, burden reduction has historically been an important justification for obtaining responses for most content items from samples of households. It is possible that greater use of sampling for content, with the consequent further reduction

-

in burden, could have the benefit of improving the quality of the response.

- Legislative and political considerations. Although the panel was explicitly instructed to set aside legal considerations in examining choice of methodology for the decennial census, such considerations cannot be totally ignored. At present, clear legislative authority exists for the Census Bureau to use sampling to obtain answers to any and all items on the form, but there is a question whether this authority would extend to the use of sampling in determining population head counts for purposes of congressional reapportionment.

The decision to adopt a particular application of sampling in the decennial census must rest on a careful assessment of the net gain or loss (compared with the alternatives) on each of the above dimensions. Because an assessment is unlikely to show net pluses on every dimension (or net minuses for that matter), it will be necessary to make trade-offs and to answer hard questions such as how much reduction in accuracy is tolerable to achieve a specified level of cost savings. Quantification of the relative importance of the dimensions is difficult. In considering promised changes in methodology, the panel has attempted to make explicit the degree to which various factors are affected.

The panel reviewed several possible applications of sampling for the count, ranging from replacement of the census with a large sample survey to the use of sampling in the final stages of follow-up. The panel concluded, for a variety of reasons, that sampling appears more likely to be cost-effective at the end of the census process than in the earlier stages. The panel supports further research directed toward evaluating the merits of limited use of sampling as part of the census enumeration process.

Taking a Sample Census

Currently, decennial census methodology involves collecting the majority of population and housing characteristics from a sample of households, who receive the “long-form” census questionnaire. (Sample sizes for the long-form items in recent censuses have ranged from 3.3 to 50 percent and are typically 20 or 25 percent.) However, counts of persons and housing units and basic characteristics such as age, race, sex, and marital status, are obtained from 100 percent of the population.

The concept of taking a sample census, that is, taking a large sample survey instead of a full census to obtain the count of the population and re-

lated basic characteristics, has been suggested as a means to effect a reduction in costs while satisfying the primary information needs served by a full census (see, for reference, Bureau of the Census, 1982a; Kish, 1979). Kish has also suggested, as a variant on the basic concept of a sample census, taking “rolling samples,” whereby a different fraction of households is enumerated each year (Kish, 1979; Congressional Research Service, 1984:175).

Miskura et al. (1984) propose several research projects intended to result in a possible design for a sample census. These include projects to develop appropriate sampling error estimates for alternative designs, to develop total error models (including sampling and nonsampling error), to investigate the theoretical reduction in nonsampling error required to obtain overall accuracy at least equal to that of a complete count, and to develop cost models and estimate their parameters for a sample census. At present, however, the Census Bureau has no plans to proceed with extensive research on a sample census, a decision the panel supported in its interim report (National Research Council, 1984:Ch. 2).

Problems Involved in a Sample Census

The panel believes that the concept of replacing the census with a large sample survey should be excluded from the Census Bureau’s 1990 research and testing program for a number of reasons that relate principally to census purposes, costs, and coverage.

The decennial census is the only comprehensive source of data for very small geographic areas such as towns, census tracts, and city blocks (see the discussion in Chapter 2). There are important needs for data about small areas, including: redistricting of national, state, and local legislative districts, which requires block counts by race to meet court-mandated criteria for equal size and compactness of districts (Bureau of the Census, no date-b), and revenue sharing, which requires population and income data for 39,000 political jurisdictions that include many very small towns, villages, and special districts. Small-area census data are also used in public planning and by the private sector for many purposes. Moreover, the model-based estimation techniques that are used to produce small-area data postcensally for revenue sharing and other purposes are recalibrated periodically against the census.

To obtain small-area population counts and basic characteristics from a sample survey to satisfy the uses outlined above with an acceptable level of accuracy would require a large sampling rate, probably 50 percent or greater for small jurisdictions. Moreover, it would not be acceptable to design a clustered area sample that included the population of only some geographic areas, such as selected counties or cities, because small-area data are needed for every political jurisdiction in the country. Hence, it would

not be possible to reduce the number of field offices and thereby effect significant savings in administrative overhead costs. Moreover, while the size of the interviewer staff could be reduced somewhat, a large sample survey would entail additional costs for drawing and controlling the sample. Finally, to select a large unclustered sample would probably require complete address listing. Given a large sampling rate, an unclustered design, and 100 percent address listing, the panel is doubtful that costs could be significantly reduced in comparison with a full census.

The panel has reviewed Census Bureau cost estimates prepared in the mid-1970s for conducting a mid-decade census on a sample basis compared with a complete enumeration. These estimates appear to bear out the contention that there would be only minor cost savings in sampling on the scale necessary for satisfaction of present demands for small-area data (see Appendix 6.1 for details).

Finally, there is the issue of completeness of coverage obtained by a large sample survey compared with the full census. There is a large body of evidence in both the United States and other countries that the census obtains more complete population coverage than even the best-executed sample survey (Redfern, 1983; Yuskavage et al., 1977). Furthermore, the coverage deficiency of sample surveys relative to censuses affects differentially precisely those population groups that are least well counted by the census in the first place. In fact, even the samples taken in conjunction with the census generally produce lower population figures than the complete census (Waksberg et al., 1973). One possible reason for this finding is that the publicity surrounding a census elicits greater cooperation from the public than can be obtained in surveys. While, of course, the Census Bureau would mount a publicity campaign for a sample census, it would be difficult to include a question like “Were you counted?” when only a fraction of the population is supposed to respond. Similarly, the field operations of a census, including follow-up and special coverage improvement programs, are geared toward finding every housing unit and person and adding missed units to the address list developed in advance of the census. For a sample census, it is unlikely that the same effort would or could be put into adding units to the sampling frame, and less complete coverage may result.

The less complete coverage obtained by a sample census compared with current methodology would have adverse implications for many important uses of census data. Concerns about inequities resulting from differential undercoverage of important subgroups of the population are already very strong. Substituting a large sample survey for the census would deepen these concerns still further—and probably with every good reason, given, as we noted before, that sample surveys appear to undercount even more disproportionately precisely those population groups already disproportionately undercounted by the census. The decennial census is also used as the basis

for the design of current surveys in both the public and private sectors and to benchmark current population estimates. Less complete coverage would adversely affect these uses of census information as well.

We believe that rolling samples would also suffer from the disadvantages just discussed for a large-scale decennial sample survey compared with a complete enumeration, namely less complete coverage and either significantly reduced reliability of small-area data or only modest cost savings. Rolling samples may offer some advantages, such as improved ability to recruit and retain high-quality field staff, but have the added disadvantage that data are not available for comparative analysis across areas and population groups at a point in time. As described in Chapter 2, many uses of census data, including redistricting, fund allocation, and public policy analysis, depend on cross-sectional measures.

Recommendation 6.1. We recommend that the Census Bureau not pursue research or testing of a sample survey as a replacement for a complete enumeration in 1990.

THE USE OF SAMPLING FOR FOLLOW-UP

Another proposed use of sampling for the count is to sample in the follow-up stage of census operations as a means of reducing costs (Bureau of the Census, 1982a, 1983a; Ericksen and Kadane, 1985; General Accounting Office, 1982). A census carried out with the use of sampling for follow-up could, for example, at a specified date after Census Day, draw a sample of addresses from which a completed census form had not been returned and follow up only those addresses. The total number of housing units and persons represented by the cases that were followed up would then be estimated and added to the number that returned questionnaires in the mail. The Miskura et al. (1984) paper outlines research projects intended to provide a sound methodological basis for designing follow-up operations to be carried out for a sample of nonresponding units. These projects are similar to those proposed in connection with conducting the entire census on a sample basis, namely to develop sampling error estimates and total error models for alternative sampling designs. These research endeavors were expected to lead to a pretest of sampling for follow-up and such a pretest was included in the Census Bureau’s initial plans for 1986 (Johnson, 1984). The test would have used a split panel design, whereby census field staff in half the enumeration districts would follow-up every household not returning a questionnaire, but follow-up only a sample of nonresponding households in the remaining districts. Unfortunately, given the realization that not all objectives could be tested with a limited number of sites, the Census Bureau decided that other objectives took higher priority and dropped the test of sampling for follow-up in 1986.

Problems Involved in Sampling for Follow-up

The panel believes that the use of sampling for follow-up has some of the same drawbacks as the use of sampling for the entire census. The Miskura et al. (1984) and Johnson (1984) documents properly observe that, for sampling in follow-up operations to be effective, increases in total error (sampling plus nonsampling errors) must be counterbalanced by comparable cost savings. Because a heavily clustered design could not be used, given that follow-up operations must be carried out in every geographic area, there would be little opportunity to effect sizable savings by eliminating entire segments of field operations. Moreover, there would be the added costs of drawing and controlling the sample. The possibilities of confusion caused by a large sampling operation concurrent with the census should not be underestimated. For example, mail returns will come in after the cutoff date for drawing the follow-up sample and would introduce practical field problems and problems of integrating the late returns with the sample. Careful attention would need to be given to the sample design and determination of sampling fractions, given the likelihood of large variations in initial mail response rates across geographic areas. For example, in 1980, Madison, Wisconsin, had a mail return rate of over 90 percent, while the rate for the central Brooklyn district office was about 55 percent (Ferrari and Bailey, 1983:59). Carrying out follow-up operations on a sample basis would also add problems for coverage improvement and coverage evaluation programs that involved matching individual records. Furthermore, because low mail return rates very often characterize areas with relatively high coverage errors, sampling at this stage would probably introduce the largest sampling error into those estimates that already suffer from the largest coverage errors.

Sampling in the Final Stages of Follow-up

In light of the fact that it is never possible to obtain a 100 percent follow-up, there may be reason to believe that sampling could prove cost-effective in the final stages of follow-up operations. It is well known that the cost to count an additional person rises sharply as one moves toward those people who are harder to locate. That is, the per case cost to enumerate people requiring multiple follow-ups or special coverage efforts is many times the per case cost for those persons who mail back their questionnaires (Keyfitz, 1979; National Research Council, 1978; see also Chapter 5).

The administrative and recordkeeping problems associated with the use of sampling are much smaller if sampling is used only at later stages of follow-up. For example, it is anticipated that a much smaller fraction of persons in the final follow-up pool would subsequently return their

census forms by mail. Certainly the total number of individuals for whom records are required is smaller if sampling is restricted to the final stages of follow-up. Therefore, the selection of the sample and recordkeeping could be handled by a smaller number of higher-level Census Bureau employees.

There is also the possibility that the use of sampling in the later stages of follow-up could lead to a decrease in the nonsampling component of error that would exceed the error introduced by sampling, thus resulting in a decrease in total error. We can imagine a situation in some regional offices in which the personnel who are involved in final stage follow-up operations vary greatly in their abilities to elicit accurate information from the nonresponding units. Total error may be reduced if, rather than using the whole field force in follow-up, only those interviewers with superior skills are employed in a probability sample of the final follow-up cases. To the extent that field personnel have differential skill levels—and there is reason to believe that qualified and dedicated personnel are becoming increasingly difficult to hire and retain (Hill, 1984)—this approach might have payoffs.

Determining the Final Stages of Follow-up

In the 1980 census, the first stage of follow-up for nonresponding households called for enumerators to make as many as four attempts to locate the residents. If no one could be found but the housing unit appeared to be occupied, the enumerators were instructed to obtain basic information from other persons, such as neighbors, resident managers, and the like. Census Bureau field staff estimate that as many as 98 percent of households were enumerated by the end of this first stage. The second phase of follow-up included attempts to locate the remaining 1 or 2 percent of nonrespondents and implementation of special coverage improvement programs such as the Vacant/Delete Check and the Nonhousehold Sources Program discussed in Chapter 5. This second stage also included follow-up of households whose questionnaires had an unacceptable rate of missing data.

To obtain appreciable cost savings from sampling in the last stages of follow-up, it may be necessary to restructure the first and second stages. One possible scenario could be to restrict the first stage to perhaps two attempts to locate nonrespondents. The second stage could then encompass follow-up on a sample basis of the remaining nonresponding households, which would represent a larger fraction of all households than the second phase of the 1980 operation. Clearly, more study is needed before recommendations could be formulated.

It would also be possible, as discussed further below, to carry out the checking of vacant units on a sample basis in a combined operation with the second-stage follow-up of nonrespondents. (In fact, the checking of

vacant units is a particular type of follow-up.) Appendix 6.2 presents an illustrative scenario and gives crude estimates of possible cost savings.

Restructuring the first and second stages of follow-up in this manner and using sampling for the second stage could have beneficial effects on the quality of the data. The 1980 census procedures did not include any special quality control measures for households enumerated in the first follow-up stage based on responses of other persons such as neighbors (called “last resort” cases). If, after a limited number of initial follow-up attempts, sampling were initiated with higher-level staff and more stringent quality-control measures, there is the possibility that better data could be obtained in the second stage for a larger proportion of households.

The Merits of Research on Sampling

On balance we doubt that sampling the entire pool of nonresponding households for follow-up will prove cost-effective, but we believe there may be important benefits from the use of sampling for households that do not respond after one or two follow-up attempts. We urge the Census Bureau to study the feasibility of sampling and to estimate components of total error in the 1987 cycle of pretests. We also advise that maximum use be made of information that can be extracted by simulating sampling with data from the 1985 and 1986 pretests. The analysis should attempt to identify stages of follow-up (first round, second round, etc.) and, for each stage, determine cost structures and patterns of response, comparing these across different sized geographic areas and areas with differing initial mail response rates. In addition, we suggest that the Census Bureau investigate methods of making the most effective use of field staffs with varying skills and determine if there are new techniques that can be applied to reduce the nonsampling components of total error.

Recommendation 6.2. We recommend that the Census Bureau include the testing of sampling in follow-up as part of the 1987 pretest program. We recommend that in its research the Census Bureau emphasize tests of sampling for the later stages of follow-up.

A great deal can be learned about the nonresponse phenomenon from an analysis of past records of the number of callbacks and the time required to obtain information from various housing units. We have urged that this analysis be applied to the 1985 and 1986 pretests, for which we believe that increased automation should make it possible to capture the follow-up history of individual households. Analysis of the 1980 census experience would also be very useful, but the necessary data were not recorded in sufficient detail.

Recommendation 6.3. We recommend that the Census Bureau keep machine-readable records on the follow-up history of individual households in the upcoming pretests and for a sample of areas in the 1990 census, so that information for detailed analysis of the cost and error structures of conducting census follow-up operations on a sample basis will be available.

Telephone Follow-up

We noted with interest the report on the telephone follow-up experiment conducted during the 1980 census (Ferrari and Bailey, 1983). A sample of units in the address lists of seven district offices that were not in multiunit structures and had not sent back questionnaires by mid-April was selected for telephone follow-up using telephone directories organized by address. (In one district office, a sample of units in multiunit structures was also drawn.) The nonresponding units not in the sample were followed up by enumerators according to standard census practice. Preliminary results indicated several advantages for the telephone technique, namely lower costs per completed interview compared with personal follow-up, lower item nonresponse rates for many items, and fewer duplicate questionnaires. Refusal rates were similar for both techniques. A disadvantage of telephone follow-up was that the directories lacked listings or had out-of-date listings for many addresses. The Census Bureau’s 1990 census research program includes further tests of telephone follow-up in 1986 (Johnson, 1984; Bureau of the Census, 1985b).

The report of the 1980 experiment, in addition to documenting results, describes in some detail operational problems that were encountered in administering the experiment. For example, a higher than expected rate of return of mail questionnaires after the sample selection date reduced the actual sample size of the telephone follow-up samples. The regular field office staff and the experiment staff also had problems working smoothly together in some offices. These kinds of problems may affect not only telephone follow-up but also sampling for follow-up in general.

Recommendation 6.4. We support the Census Bureau’s plans for further testing of telephone follow-up procedures in 1986. We recommend that the Census Bureau review the implications for sample-based follow-up operations of the operational difficulties that were encountered in the 1980 telephone experiment.

SAMPLING FOR COVERAGE IMPROVEMENT

Along with proposals to follow up a sample of nonrespondents, proposals have been put forward to conduct specific coverage improvement

programs on a sample basis. It is suggested that using sampling for coverage improvement has the potential to reduce costs, speed the completion of the census, and reduce nonsampling error and total error. With regard to considerations of data quality, coverage improvement programs can result in erroneous enumerations (overcount) as well as adding missed households and persons to the census. If coverage improvement programs are carried out on a sample basis by higher-quality staff using careful procedures, it is possible that quality may be improved—although experience with post-enumeration coverage evaluation surveys would not appear to support this hypothesis. On the negative side there are problems of costs and delays in estimation raised by the use of sampling for coverage improvement programs.

In 1970 the Census Bureau carried out two coverage improvement programs, the National Vacancy Check and the Post-Enumeration Post Office Check, for samples of households. In 1980 there was a deliberate decision to implement all procedures on a 100 percent basis and minimize imputation of entire households. There is evidence that the 1970 National Vacancy Check, which involved revisiting a small sample of units originally classified as vacant and making a careful determination of their status as of Census Day, came close to measuring the actual net undercount of occupied housing units. The 1980 Vacant/Delete Check, while importantly reducing undercount, also contributed to overcount (see Chapter 5).

Miskura et al. (1984) propose to consider the benefits of sampling for coverage improvement and describe four research projects geared toward developing sample-based coverage improvement programs for 1990:

- Work on sample design issues, such as development of a sampling frame, choice of sample unit, and possible stratification;

- Investigation of selection and data collection methodologies;

- Research on estimation from the results of coverage improvement sampling operations; and

- Research directed at translating the findings from the estimation work into required additions to the census, for example, imputation procedures to add “persons” corresponding to the estimated undercount.

The Census Bureau’s 1986 pretest plans initially included a proposal to simulate implementing the Vacant/Delete Check on a sample basis. Simulation was proposed because a sample of vacant units at one pretest site would be too small to support reliable analysis (see Johnson, 1984). Current plans do not include this research (Bureau of the Census, 1985b).

In Chapter 5, the panel recommended that the Census Bureau carefully evaluate previously tried and proposed coverage improvement procedures

to select only the most promising for inclusion in the 1990 research and testing program and to drop the rest from further consideration. For the procedures that are retained in the test plans, the panel recommends that the Census Bureau consider whether sampling offers any advantages. In accord with prior recommendations in this chapter, the panel suggests that sampling will be advantageous only for those programs that are carried out in the later stages of follow-up and where there is the possibility to achieve substantial cost savings.

Reviewing the coverage improvement procedures discussed in Chapter 5, sampling is not recommended for any of the address checks carried out prior to Census Day. These programs are important for developing a complete list of housing units, which is an essential tool for obtaining complete population coverage. Among the coverage improvement procedures implemented after Census Day, the Vacant/Delete Check stands out as a procedure that: (1) proved effective in reducing undercount in both 1970 and 1980 and will undoubtedly be used in 1990, and (2) cost a large sum of money in 1980 (at least $36 million) and therefore offers the potential for cost savings.

The panel therefore supports research on the use of sampling for the Vacant/Delete Check, particularly as the experience in 1970 with conducting this operation on a sample basis suggests that a carefully controlled sample operation affords the opportunity to reduce erroneous enumerations (overcount) as well as add overlooked households and persons to the census count. The panel urges that such research be carried out as soon as feasible.

Recommendation 6.5. We recommend that the Census Bureau consider the use of sampling for those coverage improvement programs that are implemented in the final stages of census operations and where there is potential for significant cost savings. We recommend that the Census Bureau simulate sampling in the Vacant/Delete Check program in an upcoming pretest.

Every census since 1940 has obtained responses for some content items from samples rather than from 100 percent of the population. The use of sampling in 1940 was very limited, but by 1980 the majority of population and housing items were asked on a sample basis (see Bureau of the Census, 1978b). We briefly recapitulate the highlights of the use of sampling for content collection in recent censuses:

- The 1940 census obtained most items from everyone; a few items were asked of a 5 percent sample of the population.

- The 1950 census extended the use of sampling for content and featured a fairly complex sample design. About two-fifths of the questions were asked on a sample basis. Sample sizes for population items were 20 percent and 3.3 percent (one-sixth of the 20 percent sample). A matrix design was used for housing sample items—each one-fifth of households was asked one or two housing items in addition to the complete count questions.

- In 1960, about three-fourths of the population and two-thirds of the housing items were asked on a sample basis. Sample sizes were 25 percent for population items and 25, 20, and 5 percent for housing items. The 1960 census first introduced the concept of “short” and “long” forms. In the first stage of census enumeration, every household filled out the short form. At every fourth residence, the occupants were also asked to complete one of two versions of a long form, each version containing the 25 percent population and housing items but either the 20 percent or 5 percent housing questions.

- The use of sampling for content in 1970 was similar to that in 1960. There was a short form sent out to 80 percent of households and two different versions of the long form. Each version included the 100 percent population and housing items and a common set of items asked of 20 percent of households, but one version included as well a set of questions asked of 15 percent of households and the other a set asked of 5 percent of households.

- In 1980, there was only one long form, but different fractions of households received the long form depending on the population size of their place of residence. In places expected to exceed 2,500 population, one in every six households received the long form, while, in smaller places, one in every two households received the long form. The overall sampling rate was approximately 20 percent. The primary reason for changing from a uniform 20 percent sampling rate to rates of 50 percent for small places (about 5 percent of the population) and 16.7 percent for all other places was to provide reliable per capita income data for use in general revenue sharing allocations for all places.

The current short-form/long-form arrangement is the result, historically, of trading off, for each possible item, the costs of putting it on the short form, on the long form, or not including it at all against the benefits of acquiring responses on the item from either a sample or a complete enumeration. The costs of including items in census questionnaires comprise increased respondent burden and hence unit and item nonresponse, increased time and resources required for processing of the information, and, perhaps

above all, increased difficulty of census operations. The Census Bureau cannot hope to collect every item that users might want. Benefits depend on how the census information collected will be used.

The Census Bureau has a long-established process for evaluating proposals for content items to include on the questionnaire and for determining whether it is acceptable to ask them only on the long form or whether they must be included on the short form. Generally, the presumption is that items should be restricted to the long form, in order to reduce burden and processing costs, unless it can be demonstrated that the data are required for very small geographic areas such as city blocks or small places (see the discussion in Chapter 2).

Sampling Plans for Content in 1990

The Census Bureau is currently in the process of obtaining reactions from data users regarding proposed content for 1990. The Census Bureau has also completed a preliminary assessment of population data needs for the 1990 census by subject item and level of geographic area detail based on a survey of federal, state, and local agencies of mandated requirements for census information (Herriot, 1984).

Current plans for the 1990 census are to continue the use of two different sampling rates for the long form as in 1980. The Census Bureau (Johnson, 1984) is also considering conducting a follow-on sample survey that would collect additional items that are not on either the long form or the short form for about 1-2 million households (1-2 percent). The sample for the follow-on survey would be drawn from households receiving the census short form and would be fielded about 2 months after the completion of nonresponse follow-up in the census. Items being considered include noncash income, disability, and education. Follow-on surveys have been conducted in connection with previous censuses, but usually directed toward specific populations and not fielded until a year or more after the census. (In this regard, the Census Bureau is considering for 1990 a special follow-on survey of residents of mobile homes; see Bureau of the Census, 1985b.)

The proposed follow-on survey of a nationally representative sample of households enlarges the set of choices with regard to inclusion of items in the census. It adds the possibility of obtaining data for items not currently on the long form for which a lower sampling rate is acceptable. It also offers the possibility of moving some items currently on the long form to the follow-on questionnaire and thereby perhaps increasing unit and item response rates in the census. Finally, greater detail can be obtained for items on the follow-on survey given the much reduced sample size, compared with what is feasible for the long form. However, the need for a follow-

on survey should be carefully assessed, as should the appropriateness of including particular items. It should not be assumed that such a survey will provide the vehicle for obtaining all the detail that the census itself cannot accommodate.

The panel had available only sketchy information on the content and purpose of the proposed 1990 follow-on survey for which a pretest is planned in 1986. The panel is concerned that the Census Bureau has not applied the same stringent criteria for determining items to include in the follow-on survey as has been the practice with regard to the long form. For example, the panel is troubled by the proposal to ask questions on noncash income, given that respondents may react negatively and that alternative data sources currently exist for information on this topic, including the new Survey of Income and Program Participation and administrative records. The panel suggests that the Census Bureau articulate explicit criteria for an item’s inclusion on the follow-on survey. From there, decisions to include items on the follow-on survey (if it is carried out) can be made using a process that is similar to the one for including items on the long form.

Recommendation 6.6. We recommend that the Census Bureau refine and make more explicit its criteria for inclusion of items in the proposed follow-on survey that is being considered for the 1990 census.

Possible Alternatives

In considering issues of sampling for content, the panel noted a few alternatives to the current short-form/long-form breakdown with or without a follow-on survey:

- Modified status quo. The sampling rates for the long form could be something other than 16.7 percent and 50 percent based on size of place. There might be three or more strata with different sampling rates for each. Perhaps there would be only a change in the sampling rates in the current two strata. The panel is not aware of any consideration of such alternatives by the Census Bureau.

- Matrix sampling for the long form. There would be several long forms each containing some items in common and some different items. The sampling frame would be divided into several groups and each group would receive a different long form. This procedure, which was followed to some extent in the 1950, 1960, and 1970 censuses, would allow a greater total number of questions on the long form. The panel believes that the logistical problems of such an approach are formidable. Moreover, user experience with two sets of data products in the 1970 census—one set based on the

-

15 percent sample and the other on the 5 percent sample—suggests that it is preferable to have one set of data records that permit cross-classifications among all items.

- One-form census with follow-on survey. The short form might be lengthened to include items that were important for small areas, for example, income. The proposed follow-on survey could include the remaining long-form items. Data from 1980 census returns suggest that a longer short form might not reduce initial response rates appreciably. Overall, the mail return rate in 1980 for short forms was about 1.5 percentage points higher than the rate for long forms. In centralized district offices, which were responsible for central cities containing hard-to-count areas the difference was about 2.5 percentage points (Turner, 1984, 1985). However, the proportion of questionnaires requiring follow-up for item nonresponse was much higher for long forms than for short forms, based on data from an experiment in the 1980 census using alternative questionnaires (see Fansler et al., 1981; Mockovak, 1982a, 1982b, 1983).

The one-form census is such a substantial departure from the current practice that it is probably only of interest for decennial censuses in the year 2000 or later. Historically, of course, censuses used to consist of only one form. The two-form census came about in order to reduce costs and respondent burden, while retaining the capability of producing small-area detail and detailed tabulations for most items. A one-form census with a follow-on survey would be likely either to be more expensive than the current practice, if the census form should include a large proportion of questions currently on the long form (particularly income, occupation, and industry, which have the highest processing costs), or to result in a severe loss of small-area and subgroup detail, if the follow-on survey included all or most of the current long-form items.

The panel has not tried to put together a comprehensive list of alternatives to the current short-form/long-form arrangement in terms of content breakdown or sampling rates, nor has it extensively analyzed the several alternatives outlined above. The current content of both the long- and short-form questionnaires is the result of an elaborate process with widespread consultation among potential users, and the panel has no specific modifications to propose. However, particularly in view of the Census Bureau’s consideration of a follow-on survey, the panel believes it would be worthwhile for the Census Bureau to explore alternatives such as those listed above. If one or more alternatives look desirable, consideration should be given to pretesting them.

THE USE OF ADMINISTRATIVE RECORDS AND SAMPLING FOR IMPROVED ACCURACY OF CONTENT

Information on the wide range of content items covered in the census typically comes from individual responses to questionnaires (although a small proportion of responses are obtained in other ways, such as through imputation). One of the methods the Census Bureau has frequently used to evaluate the quality of reporting in the decennial census is to reinterview a sample of census respondents after Census Day. Matches with other surveys such as the CPS and with administrative records have also been used for content evaluation. To date, virtually all content evaluations have been carried out on a postcensal basis (Bureau of the Census, 1978b; Miskura and Thompson, 1983). The results have been used to improve questionnaire design in subsequent censuses as well as to inform users of census data about limitations in the statistics, but have not been used to alter responses to the census itself.

Miskura et al. (1984) discuss the possibility of making an integral part of the census enumeration the use of survey procedures to reinterview samples of households to verify their responses and perhaps adjust content items. They propose several research projects in this area. Most of their discussion, however, concerns reinterview operations, such as the Vacant/Delete Check, that are more properly characterized as coverage improvement programs designed to add occupied housing units and persons to the count rather than to change responses to content items.

Brown (1984) discusses several kinds of uses of administrative records for content collection and evaluation:

- Content evaluation. Administrative records are frequently used for this purpose. For example, an evaluation of reporting of utility expenditures in 1980 compared census responses with administrative records from utility companies.

- Content improvement. Brown discusses the possible use of administrative records as a source of values for imputation of missing data in the questionnaire.

- Content collection. Brown notes (p. 5) that “the use of administrative records as a source of some census data may reduce respondent burden and improve the quality . . . without incurring enumeration costs.”

- Administrative records census (ARC). Brown reviews proposals to replace the census both for the count and for content with data developed from administrative records, as is currently done in some European countries.

The panel considered the use of administrative records for content collection and improvement but did not consider the issue of an administrative records census. (Chapters 5 and 8 review uses of administrative records for coverage improvement and coverage evaluation.) The panel has made clear its belief in the importance, for 1990, of maintaining the traditional concept, of enumeration as the heart of census methodology. However, the panel believes that administrative records can make important contributions to the census, particularly in the area of improved accuracy of content.

The Importance of Improving Accuracy of Content

The concern over completeness of population coverage in the census can obscure equally valid concerns over the accuracy of the content. Analysis of the fund allocation formula for general revenue sharing, for example, has shown that the per capita income component of the formula is more important than the population component in determining the distribution of funds among jurisdictions (Robinson and Siegel, 1979; Siegel, 1975). Yet reports of income in the census, as in household surveys, are known to be subject to large errors (Bureau of the Census, 1970a, 1973a, 1975b). These facts suggest that some resources can be usefully directed to improving the accuracy of content.

Evaluation research has documented problems in the reporting of many other items in the census besides income. The panel believes that serious attention should be directed to research that might lead to improved accuracy of selected census content items. We believe a research program should include design of operations to verify responses as part of the census enumeration and, as a corollary, consider the issue of adjusting census reports based on the outcome of such verification operations. We also support research into the possibility of obtaining some data items by methods other than traditional census responses. The primary alternative source is administrative records. Obviously, not all items can or should be included in verification or alternative data collection operations. For the content improvement programs that appear worthwhile, sampling will often be necessary to make the process manageable in the field and to keep costs within reasonable bounds.

Because programs to adjust census reports based on verification or alternative data collection operations have rarely been a part of decennial census methodology, it would be prudent for the Census Bureau to set forth and follow a step-by-step research and testing program. Extensive research should be concentrated on a few key items.

Recommendation 6.7. We recommend that the Census Bureau conduct research and testing in the area of improved accuracy of responses to

content items in the census. We recommend further that the content improvement procedures examined not be limited to reinterviews of samples of respondents, but include the use of administrative records.

Improving the Accuracy of Housing Items

In considering the issue of content improvement, the panel looked most closely at questions on structural characteristics of housing units, particularly the item on age of the structure or year when the structure was built. We recognize that there are many other content items, such as income, that should be reviewed to identify means of improving their quality. However, time constraints precluded examining other items besides housing structure characteristics. The housing items offer the important advantage that concerns over possible invasion of privacy from using administrative records as a data source seen very unlikely to arise in contrast to the use of administrative records to obtain, for example, income data.

Age of structure is an important component of one of the two fund allocation formulas for the Community Development Block Grant Program. The intent of this formula is to direct funds to older, declining cities in which the housing stock includes a disproportionate share built prior to 1940 (Gonzalez, 1980). Reporting of this item in the census has observable problems (Bureau of the Census, 1972, 1975a; Katzoff and Smith, 1983). The nonresponse rate is fairly high, as is the index of inconsistency (a measure of the difference between census reports and reports obtained in reinterviews for a sample of census respondents). It has been observed that, in some cities, the proportion of housing reported as being built before 1940 has been increasing rather than decreasing.

It is not surprising that this item should be poorly reported. People who rent their living quarters, particularly if they recently moved into the unit, would be unlikely to have accurate information regarding the age of the structure. Even homeowners may be uncertain about when their homes were built. It would seem that buildings housing several families, such as apartments or condominiums, will be those for which response errors are largest. For these structures, information on age is likely to be available from administrative sources such as assessment and tax records. A specific suggestion for the use of administrative records for a sample of structures to obtain better data from the census on age and related items is outlined in Appendix 6.3.

A second set of items on the 1980 census form that deserves comment is the set of questions on utility bills. The discussion by Tippett and Takei (1983) establishes that there is an upward bias on the order of 50 percent in the responses to these items. A bias of this order strongly calls into question the usefulness of retaining such questions on the census form. Alternative

methods of collecting such data, in particular from the utilities, should be considered.

We understand that the Census Bureau is considering testing questionnaires that would ask owners or managers of apartment buildings the items on the structure, such as year built, number of units, condominium/cooperative status, heating equipment, fuels used, source of water, etc. This method is used in the censuses of several European countries at present (Redfern, 1983). We believe that it is worthwhile to explore this approach, but we do not feel it should replace research on the use of administrative records.

For some housing items it may be appropriate to consider obtaining data from administrative records and dropping the items from the census. For example, if the primary use for age of structure is as input to the community development block grant formula, and cross-tabulation of this item with other census items is of low priority for users, then a cost-effective approach would be to devote resources to gaining access to and improving administrative records for the date of construction and to eliminate this item from the census questionnaire.

There are problems in using administrative records to obtain housing structure items. Records are kept in different ways and vary in quality and accessibility in different jurisdictions. For example, records such as tax assessors’ rolls are highly computerized in some jurisdictions, while maintained on paper in other areas. The number and types of characteristics recorded for each property also vary (see Bureau of the Census, 1984a). Nonetheless, investment in research and testing of the use of administrative records for housing structure items offers the potential to improve the accuracy of the data while reducing respondent burden in the census (or, alternatively, permitting other useful items to be put on the questionnaire). Similarly, research into the feasibility of obtaining utility expenses from utility company records would appear very worthwhile.

Recommendation 6.8. We recommend that the Census Bureau investigate the cost and feasibility of alternative ways of obtaining data on housing structure items. Possibilities include: (1) obtaining housing structure information on a sample basis from administrative records and using this information to verify and possibly to adjust responses in the census; (2) obtaining structure information solely from administrative records and dropping these items from the census; and (3) asking structure questions of a knowledgeable respondent such as the owner or resident manager. We recommend that any trial use of a “knowledgeable” respondent procedure include a check of the data obtained from such respondents against data from administrative records.

APPENDIX 6.1

COST ESTIMATES FOR A SAMPLE CENSUS

At various times during the 1970s, the Census Bureau prepared cost estimates for conducting a mid-decade census. These estimates covered several different scenarios, including a large sample survey. The estimates were very rough and a mid-decade census has never been conducted, so that there is no experience with which to validate the numbers. Nonetheless, the estimates give a range for the proportionate cost of a large survey compared with complete enumeration.

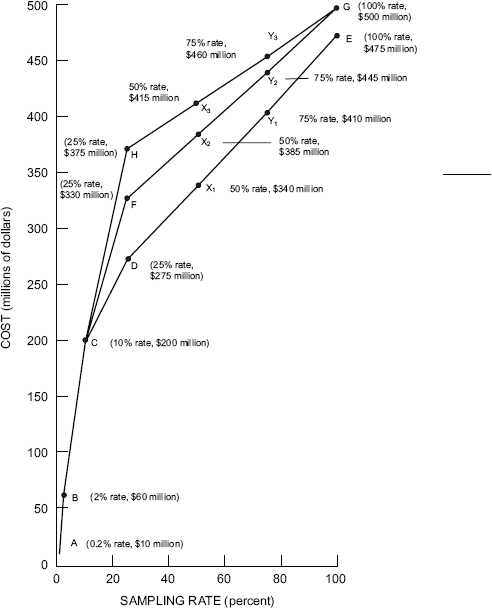

Figure 6.1 shows several lines plotting costs against sampling rates developed from the Census Bureau estimates for a mid-decade census. These lines indicate that a 50 percent sample survey (the x’s on the chart) would cost about 70 to 80 percent of the cost of a complete census and that a 75 percent sample survey (the y’s on the chart) would cost about 85 to 90 percent as much.

The coefficient of variation for an estimate of the number of blacks for places of different sizes based on sampling rates of 50 percent and 75 percent would be approximately as shown in Table 6.1. For each size place, it is assumed that the black population is about 12 percent of the total. The table also assumes that the sampling rate used would not vary by size of place.

FIGURE 6.1 Census costs estimated for varying sampling rates.

NOTE: All cost estimates were developed assuming 1976 dollars and estimated 1985 workloads (number of housing units).

SOURCE: Line ABCDE: Department of Commerce (1976:1-2, A-111; Bureau of the Census (1976c). Line ABCFG: Point F adjusts Point D costs of $275 million by $55 million, representing planned coverage and other improvements for the 1980 census that the Census Bureau factored into the Point E estimate but not the Point D estimate (see Bureau of the Census, 1976b:level 3 worksheet). Point G adjusts the Point E estimate of $475 million by $25 million, representing workload increase from 1980 to 1985 that the Census Bureau factored in for all estimates except that for Point E (see Bureau of the Census, 1976c:Explanatory Notes). Line ABCHG: Point H represents the result of multiplying the Point G estimate by an estimate, developed by the General Accounting Office in 1971, of the proportion that the cost for a 25% sample survey would be of the cost for a full census (General Accounting Office, 1971:1).

| Place Size | Coefficient of Variation for Estimate of Black Population (%) | |

| 50% Sample | 75% Sample | |

| 10,000 | 5 | 3 |

| 5,000 | 7-8 | 5 |

| 2,500 | 10 | 7 |

| l,000 | 15 | 10 |

NOTE: The black population is assumed to represent about 12% of the total for each area. The calculation of the coefficient of variation includes a factor of 2 for the design effect resulting from sampling entire households rather than conducting a simple random sample of persons.

SOURCE: Calculated from Herriot (1984:Table 1).

APPENDIX 6.2

ILLUSTRATIVE FOLLOW-UP SCENARIO USING SAMPLING

Census Bureau staff have estimated that unit nonresponse follow-up for the 20 percent of households that did not mail back their questionnaires in 1980 cost about $145 million.1 Follow-up was conducted in two stages in 1980. During the first stage, enumerators were instructed to make up to four callbacks to try to complete an interview. Households for which no information was obtained during this stage, even from neighbors or landlords as a last resort, were followed up as part of the second-stage operation.

Data are available for a few district offices in 1980 on the number of callbacks required for enumerators to obtain an interview from a nonresponding household and on the costs of completion. These data (Ferrari and Bailey, 1983) indicate that about 1.5 calls were required during the first follow-up stage for enumerators to complete an interview, that each completed interview cost about $3.90, and that about 3 percent of cases were not resolved during the first follow-up operation.

Table 6.2 uses the above, admittedly limited, data to develop a hypothetical distribution of households requiring follow-up by number of calls to obtain a filled-in questionnaire and the associated costs. The scenario shown assumes a two-stage follow-up operation with up to four callbacks allotted in the first stage.

If the first follow-up operation was restricted to two calls and the remaining nonrespondents were sampled at a 25 percent rate in the second stage of follow-up, the cost structure would appear as in Table 6.3. Net savings might be about $35 million ($146 minus $111 million) if the lower-bound estimate of the costs of a 25 percent sample compared with a complete effort is used (from Figure 6.1). If the higher-bound estimate is used, so that each call costs $12 in the second stage of follow-up with a 25 percent sample, then the total costs shown in Table 6.3 would be $126 million ($66 plus $60), and net savings might be about $20 million from the use of sampling ($146 minus $126). If the Vacant/Delete Check were also conducted on a 25 percent sample basis, savings for this program might be in the range of: $36 million × (100 – 58)/100 = $15 million, to $36 million × (100 – 75)/100 = $9 million. In total, the savings from conducting both nonresponse follow-up and the Vacant/Delete Check with the use of sampling might be in the range of $30 to $50 million, or about 3 to 5 percent of the total cost of the 1980 census. This scenario makes no

__________________

1 Personal communication from Peter Bounpane to the Panel on Decennial Census Methodology, March 9, 1984.

| Housing Units | Callbacks to Complete | Number of Callbacks | Cost ($) ($4/call) | ||

| Number | Percentage | ||||

| First follow-up | 8.5 | 9.7 | 1 | 8.5 | 34.0 |

| 4.0 | 4.5 | 2 | 8.0 | 32.0 | |

| 2.0 | 2.3 | 3 | 6.0 | 24.0 | |

| 1.0 | 1.1 | 4 | 4.0 | 16.0 | |

| Subtotal | 15.5 | 17.6 | 26.5 | 106.0 | |

| Second follow-up | 2.0 | 2.3 | 5 | 10.0 | 40.0 |

| Total | 17.5 | 19.9 | 36.5 | 146.0 | |

NOTE: Number of housing units, number of callbacks, and cost are in millions; 17.5 million housing units is about 20% of the total count of 88 million housing units in 1980.

SOURCE: See discussion in Appendix 6.2.

| Housing Units | Callbacks to Complete | Number of Callbacks | Costa ($) | |

| First follow-up | 8.50 | 1 | 8.5 | 34.0 |

| 4.00 | 2 | 8.0 | 32.0 | |

| Subtotal | 12.50 | 16.5 | 66.0 | |

| Second follow-up | 0.50 | 3 | 1.5 | 13.5 |

| 0.25 | 4 | 1.0 | 9.0 | |

| 0.50 | 5 | 2.5 | 22.5 | |

| Subtotal | 1.25 | 5.0 | 45.0 | |

| Total | 13.75 | 21.5 | 111.0 | |

NOTE: Number of housing units, number of callbacks, and cost are in millions.

aCosted at $4 per call in the first follow-up stage and $9 per call in the second follow-up stage, assuming that a 25% sample costs about 58% of a complete effort (see Appendix 6.1—note that 58% is the lower-bound estimate; 75% is the upper-bound estimate).

allowance for additional expenditure on each call that might be made to achieve higher quality through sampling.

The selection of a 25 percent sampling rate is purely for illustration. The impact of this rate and others on the quality of the population estimates for small areas would need to be assessed. We note that the overall rate of contact for the total population of an area using a 25 percent second-stage follow-up sample implemented after two calls in the first stage would be about 95 percent for an area with “average” unit nonresponse of 20 percent, while the rate of contact would be under 90 percent for an area with a 50 percent nonresponse rate.

APPENDIX 6.3

IMPROVING DATA ON HOUSING STRUCTURE ITEMS: A SUGGESTED METHOD

The panel offers the following scheme as a suggestion for obtaining more reliable data on age of structure and related housing items. The basic concept is to develop a sample of structures from the address lists compiled for the census and to obtain data from local administrative records about the characteristics of the structures in the sample. It may prove most feasible to carry out this scheme in urban areas in which census address listings and identifiers carried on local administrative records can most readily be matched.

Prior to the census, a reasonably complete list of housing unit addresses is constructed. Units that have the same basic address (such as Apt. A and Apt. B at the same street number) can initially be considered to be part of the same structure. Hence, it is possible to draw a sample of basic addresses that is a good proxy for a sample of structures.

The precise design and size of the sample would depend on the nature of the costs, among other considerations. We outline one possible procedure. Assume that the sample of basic addresses or structures is drawn with the probability of selection proportional to the estimated number of units in the structure. For concreteness, assume that single-unit buildings are sampled at a rate of 1 in 10, duplexes are sampled at a rate of 2 in 10, and so forth, up to structures with 10 or more housing units that are sampled with certainty. Administrative records data for age of structure and other items would then be obtained for the structures in the sample.

The sample of basic addresses or structures can be linked to the sample of housing units in the census as follows. Assume that one-fifth of the households are to receive the census long form, which asks for age of structure and related housing items. Given that the sample of basic addresses is specified at the time of the mailing of the census forms, all of the long-form households could be selected from those addresses. Specifically, one scheme would be to send long forms to: all single housing unit structures that are in the sample of basic addresses, two households in all other selected structures with less than 10 units, and one-fifth of the households in all structures with 10 or more units. Recalling the sampling rates for different sized structures, this will achieve a one-fifth long-form sample for structures with more than one unit. To achieve a one-fifth long-form sample of single-unit buildings, it will also be necessary to send long forms to single-unit structures not in the sample of basic addresses. This sampling scheme has the drawback of increasing sampling variance for the long form due to the clustered design. However, it has the great advantage that all of the long-form sample for people living in structures with two or more housing units

is included in the sample of basic addresses. Hence, data collected from administrative records for these structures are available to verify or to use in place of responses to the census.

Two options are available with respect to the question on age of structure in the census. It could be asked on the census form or it could be omitted. Assume that the question is retained on the census form. The simplest processing method would be to use the value obtained from administrative records for all individuals residing in the structures that are in the sample of basic addresses and to retain the answers of individuals not in the sampled structures. It would also be possible to use regression-type procedures to modify responses of individuals in structures that are not in the sample based on the information obtained for the sampled structures.

Now assume the question is not included on the census form. The values obtained from administrative records could simply be appended to the census data records for persons in structures that are in the sample of basic addresses. For persons not in sampled structures, it would be possible to assign values obtained from sampled structures located in the same area. This should be a very effective procedure in areas in which large groups of units, such as apartment complexes or suburban housing developments, were constructed at the same point in time.

This page intentionally left blank.