3

Six Widely Used Methods to Improve Quality

Key Points Made by Individual Speakers

- The six strategies under consideration have much in common, including an interdisciplinary grounding, the use of assessments to identify problems, and benchmarking to measure progress. (Atun)

- The quality movement has grown out of the attempt to take the vast amount of evidence and guidelines afforded by modern science and capture them in practical ways. (Barker)

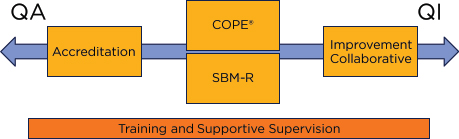

- Quality assurance tools are those that calibrate the performance of a system to certain standards. Quality improvement tools are more concerned with changing one area of a system, less with routine measuring against normative standards. The six methods discussed at the workshop fall across the continuum from quality assurance to quality improvement. (Barker)

- There is a need for rigorous evaluations on quality of care programs, but evaluating complex social interventions presents challenges, and there is limited funding for such work. (Cordero, Necochea, vanOstenberg)

- Implementers and funders of global quality programs would benefit from clear guidelines about what portion of spending to direct to programming and what portion to amassing evidence. (Necochea)

The next session introduced the six methods listed in Box 1-1: accreditation, clinical in-service training, COPE®, improvement collaborative, SBM-R, and supervision. Rifat Atun of the Harvard School of Public Health

gave an orientation to these six methods based on the standing committee’s November 2014 meeting. The methods have two distinct components: the hardware, meaning the pieces of the intervention and the way those pieces fit together, and the software, meaning each intervention’s unique design and the style with which it is implemented in different places.

Atun stressed some common elements of the six methods under question. All are multi-disciplinary, drawing on processes from social science, medicine, and management. They all rely on the use of assessments to identify problems and benchmarking to measure progress. Each one has an element of ongoing problem solving. In some of the methods, this means consciously employing a plan-do-study-act cycle; in others, the recursive element is the re-training or re-accreditation process. Facilitators or external advisors have a place in all the methods, though the prominence of the local team in solving problems varies.

Atun identified six criteria on which the methods could be evaluated. First is the cost-effectiveness, the results the intervention elicits relative to its price. The method’s affordability is a similar concern, referring to the overall costs incurred by the host country. The feasibility of the method—whether it is realistic to implement the program in a range of settings where there are different resources—is another important factor to discuss. Along the same lines, the replicability of results in new settings and the scalability, or ease of expansion, are two features that funders need to understand. Lastly, the sustainability of the method, or the extent to which a program can be integrated into a health system, is of particular value both to external aid agencies and to the countries that host them.

Managers often struggle to identify what tools work in which contexts, a difficult task when the tool in question is a complicated social intervention. Randomized trials have recently gained prominence outside of health, with Jeffrey Sachs and others undertaking innovative cluster randomized designs to test development projects. Although randomized trials are still the gold standard evaluation technique, they are a bit reductionist in relation to complex quality improvement programs. Even if cluster randomized trials of the different interventions show success, it is not always possible to say which process or tool drove the success, or to isolate effect sizes for different pieces of the intervention. A careful step-wedge design, with elements of the intervention introduced in sequence, would be a suitable design, but in practice may be difficult to achieve given the interdependence of the constituent elements of quality improvement interventions. Further, the people who work most closely with the methods do not see the components as different pieces that can be broken apart, but rather as a whole program. Identifying the best methods to evaluate quality improvement and other complex interventions is a challenge facing the field.

THEORIES OF CHANGE

Evaluating interventions requires first understanding how they work, specifically the theories of change that explain how different actions cause behavior change. Pierre Barker of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement gave the audience a theoretical grounding on the topic. Quality improvement aims to change the performance of a system not by adding or reducing the resources directed to it, but by rearranging them, much the way roads and traffic laws rearrange the motor traffic in a city. The quality movement, as Barker described it, has grown out of an attempt to take the vast amount of evidence and guidelines afforded by modern medicine and capture them in practical ways.

Taking guidelines and implementing them, particularly at large scale, was a concern of W. Edwards Deming, a founder of modern quality improvement. Barker explained that scale and feasibility depend on what Deming described as the psychology of change, the way of marrying the knowledge of the evidence with the knowledge of management. In Deming’s model, which was not designed for health, the first step in quality improvement is to define the system and its limits—the specifications within which the system works. The quality controllers are responsible for making constant, small changes to keep the system working within defined parameters.

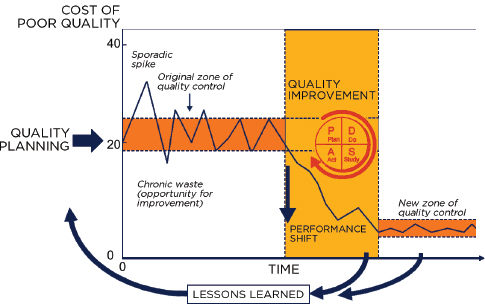

A complementary influence on quality improvement came from Joseph Juran, who described a trilogy of quality control, quality planning, and quality improvement. Barker placed these terms in the health context, explaining that quality planning refers to policy decisions affecting the way resources are coordinated and the checks in place to ensure accountability, while quality control refers to national guidelines and systems for professional oversight and accreditation and uses tools such as checklists and standards. Figure 3-1 shows how all three pieces of the Juran trilogy drive changes in the way systems perform.

Barker then explained the difference between quality assurance and quality improvement methods (see Table 3-1). Quality assurance has an overarching goal of calibrating the performance of a system to certain standards; managers drive this change and enforce compliance targets as much as possible. Quality improvement tends to give attention to change in one area of the system; it is less about routine measuring against normative standards and more about all participants teaching and learning from each other.

Quality assurance and quality improvement techniques differ in how they take shape on the front line, Barker continued. He described how managers of quality assurance programs often hit systemic barriers when implementing programs. The barriers are then reviewed in a plan-do-study-act cycle. The information from this cycle influences future iterations of the

FIGURE 3-1 All three elements of the Juran trilogy are needed to improve outcomes.

SOURCE: Juran, J. M., and A. B. Godfrey. 1999. Juran’s quality handbook. New York: McGraw-Hill. © McGraw-Hill Education. As presented by Barker on January 28, 2015.

TABLE 3-1 Differences Between Quality Assurance and Quality Improvement Methods

| Quality Assurance (QA) | Quality Improvement (QI) | |

| Performance goal | Perform to standards (controls) across multiple parts of the system | Aspire to a best performance goal for a focused improvement area |

| Measurement | Periodic inspection of past events (large set of measures of inputs and/or processes) | Continuous tracking of current activity (few key processes linked to outcome) |

| Data tracking | Before and after change | Continuous (e.g., run charts) |

| Data system | External (e.g., inspection tools) | Internal (e.g., registers and tally sheets) |

| Changes | Standards driven; normative; can be linked to frontline system analysis | Theory driven; adaptive; always linked to frontline system analysis |

| Motivation for change | Management-led; compliance; incentives; competition | Shared governance; internal motivation; “all teach all learn” |

| Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) | Management planning with single “slow” (months) intervention cycle; can use frontline rapid cycle to respond to defects | Frontline planning; rapid cycle (days/weeks) is core activity |

SOURCE: Barker, 2015. Reproduced by permission of Pierre Barker, Institute for Healthcare Improvement (unpublished).

program, as well as changes to the normative standards. In quality improvement programs, the problem is taken straight to the front lines, where staff are asked to plan the necessary changes and there is great emphasis put on rapid plan-do-study-act cycles. Staff implement the proposed changes, and the success or failure is shared among all parties at the same time. Almost all modern quality improvement programs draw on the concepts of the Juran trilogy. The methods under discussion at the workshop set clear aims, establish terms for what should be considered improvement, and determine actions that will elicit the desired improvements. All the methods are grounded to some extent in the plan-do-study-act cycle, although the length of the cycle may vary. The six methods from the workshop fall across the quality assurance and improvement spectrum (see Figure 3-2). Barker admitted that all the methods have aspects of what might be considered a quality assurance orientation and a quality improvement slant. Depending on how it is implemented, each method could be placed differently along the continuum. In general, however, he thought that COPE® and SBM-R would tend to fall in the middle, with a slight tendency toward quality assurance, while improvement collaborative is meant to be more of an improvement tool, though it does reach into quality assurance at times. Barker saw training and supervision as general support to the whole continuous process; it is not possible to say exactly where any particular training or supervision program might fall.

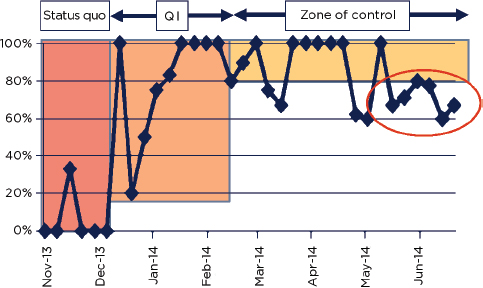

Barker used an example from his fieldwork in sub-Saharan Africa to illustrate these theories. One way to decrease neonatal mortality is to give women who go into preterm labor a dose of the corticosteroid dexamethasone to mature the baby’s lungs, but this intervention was not happening at a hospital in Malawi in late 2013 (see Figure 3-3). After a quality improvement program, the percentage of eligible women receiving the corticosteroid increased rapidly and stayed that way, with a few lapses during manage-

SOURCE: Barker, 2015. Reproduced by permission of Pierre Barker, Institute for Healthcare Improvement (unpublished).

FIGURE 3-3 Percentage of eligible women receiving dexamethasone before, during, and after a quality improvement (QI) intervention. The red circle indicates a drop in compliance that should be seen as a warning signal.

SOURCE: Barker, 2015. Reproduced by permission of Pierre Barker, Institute for Healthcare Improvement (unpublished).

ment changes, until mid-2014, when compliance started to dip. This dip in compliance occurred at the flagship hospital as well as the other program hospitals. On a later visit to Malawi, Barker found the program almost abandoned. The government had, for many reasons, decided not to pursue the corticosteroid program, so women were no longer even being assessed for gestational age (necessary to determine if their labor is preterm), and supplies of the necessary drug had run out. The program’s success could not be sustained because it depended on larger systemic factors, including the commitment of management up to the national level and the procurement of essential medicines. In this example, the hospital is something of a micro-health system, but sustaining success depends on factors beyond the hospital itself, such as the district policies, management’s commitment, and a reliable medicines supply.

The sustainability of different quality improvement programs is a priority in global health, and some participants struggled with the extent to which successful techniques can be generalized. Barker concluded that, within a country, there is some generalizability of implementation approaches and that emphasis on context, though helpful, should not obscure these common threads.

TOOLS AND PROCESSES FOR QUALITY IMPROVEMENT

In the next session, experts in each of the six methods shown in Box 1-1 oriented the audience to their tool: the causal pathway through which it works, the key processes, and the relative strengths and weaknesses.

Client-Oriented, Provider-Efficient Services (COPE®)

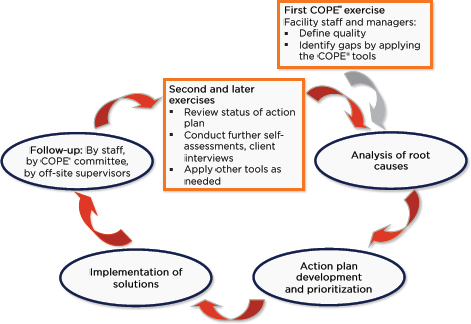

Carmela Cordero of EngenderHealth started the session with a description of COPE®. COPE® is one part of EngenderHealth’s suite of quality improvement interventions. It was developed in Kenya and Nigeria in the late 1980s, drawing on the work of Deming as well as other contemporary thinkers who were interested in clients’ rights and providers’ needs. Organizational psychology is important to COPE®; the method assumes that problems are more meaningful and solutions more effective if they come from facility staff.

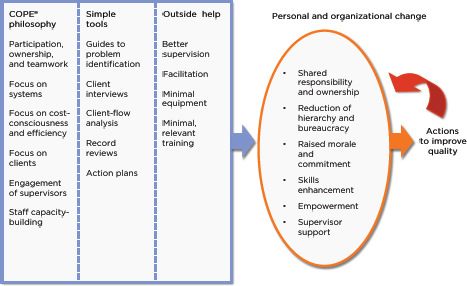

The COPE® package has four main pieces: a handbook; a self-assessment guide that requires a systematic analysis of how services are provided; client interview guides that set out how staff members should talk to clients and identify what clients consider to be good quality care; and a client flow analysis to monitor how long clients are waiting and how long their contact with providers lasts. Figure 3-4 shows how the process and tools used in COPE® support continuous assessment of health services.

FIGURE 3-4 The processes and tools in COPE®.

SOURCE: Cordero, 2015. © Reproduced by permission of EngenderHealth.

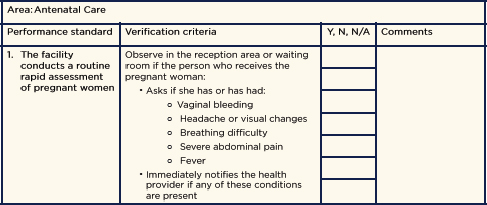

COPE® exercises put a good deal of emphasis on local understanding, including how patients and providers perceive good quality care. External facilitators do not influence these discussions: their role is to help the local team analyze their service processes and identify the root causes of their problems. The COPE® facilitator is responsible for supporting local staff in developing an action plan. This includes establishing a local COPE® committee to start the process of implementing changes to the system. The process is meant to be highly participatory, based on the assumption that participating in the process gives workers a stake in the results (see Figure 3-5). The process also requires attention to recordkeeping and data analysis. Figure 3-6 shows the conceptual pathway through which COPE® elicits change.

Cordero described the emphasis on clients and communication as being among COPE®’s main strengths. Often the COPE® process is the staff’s first introduction to the concept of quality, and it helps that a set of tools for problem solving accompanies the process, as does an introduction to relevant standards and guidelines. On the other hand, the process requires a lot of energy and commitment from both the organization’s leaders and the local government, which can be seen as weaknesses. She closed her

SOURCE: Bradley, J., and S. Igras. 2005. Improving the quality of child health services: Participatory action by providers. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 17(5):391–399. Reproduced by permission of Oxford University Press and the International Society for Quality in Health Care. As presented by Cordero on January 28, 2015.

SOURCE: Cordero, 2015. © Reproduced by permission of EngenderHealth.

presentation by observing that COPE®, like all quality interventions, is not the only way to effect change and that the method works best when it is a piece of a larger quality strategy.

Standards-Based Management and Recognition (SBM-R)

Edgar Necochea of Jhpiego opened his presentation by reiterating Cordero’s point that all of the methods being discussed can work under certain circumstances, and his presentation described what circumstances encourage success with SBM-R. He described SBM-R as a standardization approach, one that attempts to bridge a gap between the evidence and practice in low- and middle-income countries. In low- and middle-income countries, staff are typically overworked in poor conditions. They have to make the most of limited resources and often have had weak pre-service education. Management can be dysfunctional and morale low. In such environments, there is no shortage of evidence about what works or failure to translate evidence into concrete guidelines. Rather, the main problem is that guidelines are shelved by overworked staff and not translated into tools for daily use.

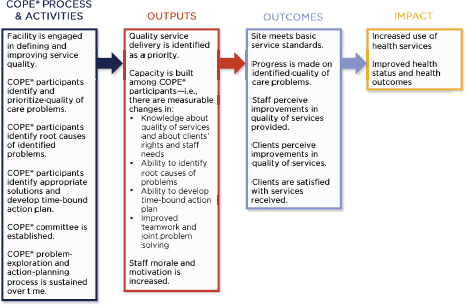

SBM-R builds on the Deming theory of quality improvement, modifying the plan-do-study-act cycle to standardize-do-study-reward as shown in Figure 3-7. The goal is to identify desired outcomes and processes that will lead to those outcomes. Clear written standards are key to SBM-R; these standards are developed with the host country counterparts and take considerable input from local stakeholder groups. Necochea shared an example of a standard (see Figure 3-8) from his fieldwork and called the audience’s attention to the standard’s emphasis on effective and respectful care, including details about both the substance of the intervention and the manner in which it should be done.

The first step in SBM-R is the training of supervisors and teams on the content of the standards and the quality improvement process. SBM-R facilitators then take a baseline assessment and work with teams, usually at health facilities, to analyze what obstacles are impeding implementation of standards. Interventions that correct these gaps must address all the factors that affect performance, including things like the provider’s knowledge, the available resources, and the health workers’ motivation. During the next stage in the process, internal and external supervisors monitor and measure the staff’s progress, so there can be ongoing recognition of success. Necochea emphasized the importance of external recognition for both the workers and the supervisors, sharing examples of how ministers, managers, and other community leaders take part in the recognition process—a way of mobilizing the community for health.

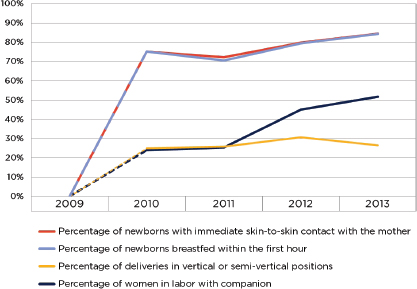

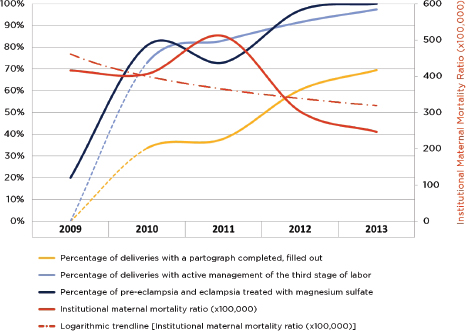

Comparative studies on the effectiveness of SBM-R show some encouraging results. Data from 102 Mozambican hospitals showed substantial

FIGURE 3-7 The modified plan-do-study-act cycle that forms the basis of SBM-R.

SOURCE: Necochea, 2015. Reproduced by permission of Jhpiego Corporation.

FIGURE 3-8 An SBM-R standard for antenatal care.

SOURCE: Necochea, 2015.

improvement in maternity practices, including treatment of eclampsia and pre-eclampsia, active management of the third stage of labor, and use of the partograph during labor, thereby reducing maternal mortality (see Figures 3-9 and 3-10). LiST1 models confirm that the observed reduction in mortality at project hospitals is consistent with the measured improvement in practice.

Necochea reviewed SBM-R’s strengths: it is a simple, intuitive, and systematic approach based on standardization of care. It also gives good attention to the human side of management: worker motivation, political will, and involvement of community leaders. Its emphasis on standards encourages the use of information technology. At the same time, the method does not work on all problems: some interventions do not lend themselves to standardization. SBM-R also takes time. Honing process efficiency and building support among local leaders can take months. This may be why SBM-R’s sustainability and integration into national health systems remain a challenge.

Accreditation

Next, Paul vanOstenberg presented on accreditation. His remarks were not limited to the accreditation process of his organization, Joint Commission International, but he did draw some examples from their work. VanOstenberg defined accreditation as “a voluntary process by which a

_________________

1 LiST, or the Lives Saved Tool, uses national demographic projections, burden of disease, and information about program effectiveness to estimate the effects of changes in the coverage of different maternal and child health interventions.

SOURCE: Necochea, 2015. Reproduced by permission of Jhpiego Corporation.

SOURCE: Necochea, 2015. Reproduced by permission of Jhpiego Corporation.

government or nongovernment agency grants recognition to health care institutions which meet certain standards that require continuous improvement in structures, processes, and outcomes.” In English, the terms accreditation, certification, and licensure are often mistakenly used as synonyms. Although the meaning of each term varies in different countries, accreditation often differs from certification in that the latter establishes an organization’s (or a person’s) competence in a particular procedure (e.g., a certified mammography center).

Accreditation is essentially a risk-reduction strategy, one that works by applying standards and evaluating adherence to them. Each institution chooses its own path to meet the accreditation standard; in that way, the process is a vehicle for different quality improvement methods. Because accreditation requires regular re-review, it encourages a culture of continuous quality improvement. Table 3-2 shows the steps in the accreditation process and estimates the amount of time they take in developed countries; in low- and middle-income countries, certain steps can take much longer.

VanOstenberg explained that accreditation’s main strengths lie in its emphasis on the whole health system: accreditors look at all the processes, materials, and staff involved with an institution and evaluate them against consensus standards. The process can encourage new working relationships across different parts of the system and in different provider networks. It also lends itself to public–private partnerships: the government often sets the standards, but leaves the evaluation and survey of them to a private accrediting body.

The emphasis on standards can be a double-edged sword, especially in low- and middle-income countries, he continued. Meeting hundreds of standards can seem impossible and overwhelming in places where resources are limited. To complicate the matter, accreditation standards can vary in their content and the way they are described, even when the standard comes from the same accrediting body. The evaluation process can also vary

TABLE 3-2 The Accreditation Process, Including the Typical Timeline in Developed Countries

| Step in the process | Amount of time to complete |

| Obtain and study standards | 6 months |

| Implement standards and prepare for the evaluation | 12–18 months |

| External evaluation | 3–5 days |

| Decision and recognition | 1 month |

| Re-review | 2–4 years |

SOURCE: vanOstenberg, 2015.

widely: some accrediting bodies allow a brief self-evaluation, while others require weeks of staff time with the external reviewers.

VanOstenberg gave an example of how the accreditation process can be adapted for very basic clinics. The SafeCare Initiative, a partnership among the South African accreditor, Joint Commission International, and PharmAccess Foundation, aims to distill the essence of accreditation—the external, standards-based quality evaluation—to more than 1,500 clinics in rural South Africa. The program recognizes clinics for reaching different levels of compliance with standards, providing loans and incentives to help the clinic management meet each level. By the time a clinic has reached the highest intermediary level, it is in a good position to try for formal accreditation.

Most of the research about the effectiveness of accreditation as a quality improvement tool comes from developed countries. VanOstenberg mentioned the dearth of literature from the rest of the world and cautioned that accreditation is a tool for continuous quality improvement, not a substitute for a national licensure system that codifies the national minimum standards for health.

Discussion

In the discussion following their presentations, the panelists gave their views on what makes a quality program sustainable. Cordero and Necochea agreed that integrating quality assurance into routine management is the essence of sustainability. Regardless of the method used, they saw continual, deliberate monitoring as essential for sustainability, as are communication and involvement of all local stakeholders. VanOstenberg noted that, when community members understand the value that quality control adds to health services, they will advocate for more attention to the problem.

Some participants discussed their experiences with implementing programs, and one person questioned whether ministries of health ever ask to see evidence that the program should work. In the early days, counterparts might ask for an explanation of how the process would work and, if it made good sense, they agreed to try it. Lately there is more demand for evidence, which the organizations are starting to amass, but the panelists agreed that the available evidence is generally weak. They have common problems identifying the best methods to evaluate their work. As a result, the evidence base is limited to small studies, studies without a comparison group, and studies demonstrating non-causal associations.

According to the panelists, one barrier to more rigorous evaluations is the limited funding for such research. The need for evidence poses difficult questions for implementing organizations and their funders. If there were clear consensus about what portion of spending goes to programming

and what portion goes to building the evidence base, some of the problem could be solved. There is also the risk that opportunities for establishing the effectiveness of quality programs are lost through insufficient attention to evaluation in the program’s planning stage. Implementing and funding agencies need to identify the intended outcomes of their program and concrete measures of its success before the project is under way. Too often they wait until the program implementation phase, at which point it is too late.

The other three methods under consideration (improvement collaborative, clinical in-service training, and supervision) were discussed in the next panel.

Collaborative Improvement

Rashad Massoud of University Research Co., LLC (URC) gave the first presentation on collaborative improvement. Although the knowledge exists, life-saving services still fail to reach patients in low- and middle-income countries. Deficits in the clinical processes and organization of the health system are at the root of the problem that collaboratives aim to correct. In the collaborative model, multiple sites work on the same problem at the same time. The method encourages learning from peers, who are all testing different ways to improve on common indicators. Collaboratives support analysis of the process for delivering care and data collection on the outcomes being studied. They use plan-do-study-act cycles and measure the effects of changes to the procedures. Collaborative improvement can address clinical or managerial topics, such as recordkeeping and waiting times. As URC implements them, the collaboratives work on problems the host country and the USAID mission have identified as priorities.

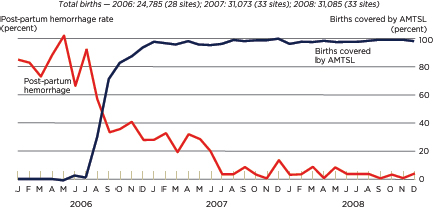

Massoud illustrated this point with an example from Niger of a collaborative that aimed to reduce post-partum hemorrhage, a major cause of maternal death worldwide, with active management of the third stage of labor (see Figure 3-11). Thirty-three participating hospitals formed quality improvement teams. URC worked with these teams, training them on technical material and on ways to make the process run more smoothly. One team promptly identified a problem with the availability of oxytocin, a uterotonic drug used to treat post-partum hemorrhage. Oxytocin is not stable at room temperature; for this reason, it is always stored in the dispensary refrigerator. Deliveries happen around the clock, but the dispensary is usually locked when the pharmacist is not on duty. After identifying this problem, the teams found creative ways to make the drug available during deliveries, such as storing a single dose on ice or putting some aside in a cooler.

The dramatic reduction in post-partum hemorrhage, shown in Figure 3-11, persisted even after the program ended in 2008. External evalu-

SOURCE: Data from Maina Boucar, URC, as presented by Massoud on January 28, 2015.

ators and a records audit both showed adherence to active management of the third stage of labor, and the consequent reduction in hemorrhage up to 2 years after the end of the collaborative. A cost-effectiveness analysis of the project found that the cost per delivery fell from $35 to $28, with an incremental cost-effectiveness of $147 per DALY averted (Broughton et al., 2013). As further evidence of the program’s sustainability, Massoud discussed how the Nigerien team replicated their work in neighboring Mali without technical assistance from URC headquarters (Boucar et al., 2014).

Other collaborative improvement programs have also shown good sustainability over time. A collaborative to improve HIV care in Uganda continued to improve adherence to treatment and clinical outcomes 2 years after the intervention phase. Similarly, the evaluation of a collaborative on compliance with best practices for management of noncommunicable diseases in the Republic of Georgia found that 40 to 91 percent of the improvement in practice could be attributed to the collaborative (see Table 3-3).

In describing the pros and cons of collaboratives, Massoud mentioned the breadth of expertise necessary to run them: experts in medicine, implementation science, and group process need to work together at the patient care, management, and policy levels. The process is time consuming, and some would say that it takes away from delivering services. At the same time, the intensity of local involvement can be seen as one of the method’s strengths. Solutions identified through collaboratives are already suited to the local context; the process of identifying and implementing these solutions builds local capacity and empowers managers to pursue con-

| Indicator | Attributable difference | p-value |

| % of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients given evidence-based medications for management on discharge | 40% | <0.001 |

| % of coronary artery disease patients put on secondary prevention (aspirin, beta-blocker, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker, statin) with all four medications | 56% | <0.001 |

| % of acute coronary syndrome patients with initial treatment (morphine, oxygen, nitrate, aspirin) recorded | 44% | <0.001 |

| % of COPD patients where all risk factors recorded (smoking, body mass index, physical activity) | 91% | <0.001 |

| % of charts of patients with COPD where all risk factors recorded anywhere in the chart (smoking, body mass index, physical activity) | 60% | <0.001 |

| % of pneumonia patients assessed for respiratory status severity | 43% | <0.001 |

SOURCE: Data from Tamar Chitashvili, URC, as presented by Massoud on January 28, 2015.

tinuous quality improvement. Other strengths of the method are its cost-effectiveness and emphasis on data management.

Clinical In-Service Training

Mike English of KEMRI Wellcome Trust gave the next presentation on clinical in-service training. He asked the group whether or not training works and then cited a systematic review from the early 2000s that showed a 10 percent median effect of training on changing provider behavior (Forsetlund et al., 2009). English conceded that training clinicians is not a particularly effective way to improve health, or at least it is far less powerful than one might assume. He concluded that training may be necessary when providers’ knowledge is not up to par, but it is almost never sufficient to sustain changes in care, especially given how quickly the training material is forgotten.

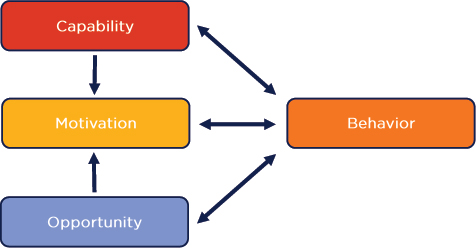

In general, training is understood as a tool that works when providers are not well informed: once they have the knowledge, they will change their practice. Many of the other presenters showed through their examples, however, that provider knowledge may have a relatively small influ-

ence on the standard of care in low- and middle-income countries. When a country runs out of dexamethasone, for example, women in preterm labor cannot be treated regardless of the provider’s knowledge. Training as a way to reliably improve practice may be an oversimplified understanding of the relationship between knowledge and behavior. English compared it to alcohol use: we all know that drinking alcohol is unhealthy, but people drink it anyway. Training can give clinicians the competence to do a task, but it cannot change larger problems with their motivation or work environment.

It is not inexpensive to run in-service training programs. In English’s experience in Kenya, a training program with qualified teachers costs about $100 per person per day. When foreign governments run the programs, the costs only increase. This analysis does not even account for the opportunity costs associated with keeping both providers and their trainers out of work for the duration of the program. Aggravating the problem is the authority of managers to choose training participants. English’s experience, seconded by many in the room, was that the same people are re-trained multiple times per year while most of their co-workers are never trained once. Students earn generous per diems at trainings, an incentive that donors have encouraged.

English explained that, in an attempt to minimize the costs of training, global health programs often use a cascading model for in-service training in which the student who attends a training is responsible for educating a larger group at his or her home office. Educational theory offers little evidence to support this model. It is extremely difficult for one person to change the behavior of a group of 25 or 30 peers. This might be contrasted with pre-service training, wherein one skilled professor, working with the right curriculum, can have a powerful influence on a large group of students.

At the same time, training can be an important part of a larger management intervention. Figure 3-12 shows the relationship between behavior change and the provider’s capability, motivation, and opportunities to practice. Clear thinking about exactly which behaviors the training intervention is meant to change and how it should change them can allow for a more efficient program evaluation. At the moment, there is not enough data about how training influences the relationships shown in Figure 3-12. English recommended more attention to the related conceptual problem of measuring quality. He cautioned that, by not investing in data, we perpetuate the lack of understanding about how management and quality interventions work.

FIGURE 3-12 The capability, opportunity, motivation model of behavior change.

SOURCE: Michie et al., 2011. As presented by English on January 28, 2015.

Supervision

Xavier Bosch-Capblanch of the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute gave the final presentation of the session, examining the role of supervision in quality improvement. His comments drew heavily from a 2008 literature review and a 2011 Cochrane review on the effects of supervision on quality of care, as well as from a more recent summary paper on improving the quality of integrated community case management programs (Bosch-Capblanch and Garner, 2008; Bosch-Capblanch and Marceau, 2014; Bosch-Capblanch et al., 2011). These papers drew on evidence published from observational and experimental studies as well as programmatic literature.

Supervision can take many forms. In health care, the term most often refers to the managerial duties of a district health officer or head of a hospital. Supervisors deal with information, such as the volume of activity in the system and caseloads reported from the periphery to the headquarters. Usually, supervision involves visits from the central office to the field offices. The frequency of such visits varies widely but is generally about every other month. Logistics and costs pose serious obstacles to more frequent supervision. In the 2008 and 2011 reviews, Bosch-Capblanch and his colleagues found that quality changes are more meaningful and sustainable when supervision is part of a bigger program that includes health worker training, incentives, and improved supply chain management.

The 2011 Cochrane review found nine studies of suitable rigor for in-

clusion: five cluster randomized trials and four controlled before-and-after designs. Bosch-Capblanch conceded that the quality of the evidence was poor; most studies had a high risk of bias. It was also essentially impossible to summarize the comparisons across the nine studies because the control and intervention groups differed in every study (see Table 3-4). The outcomes chosen also varied widely from health worker performance to the quality of chart documentation in hospitals. The review concluded that supervision elicits no certain, long-term effect on quality of care. Ultimately, supervision is a complicated intervention; it is implemented in many different ways and usually accompanied by other quality improvement measures. The literature is not always clear about separating the supervision intervention from the incentives that go along with it, such as bonus pay or supply chain reform.

Bosch-Capblanch echoed English’s sentiment that it is difficult to articulate the causal pathway by which supervision changes health outcomes, a problem his team has been struggling with as they update the Cochrane review on supervision and quality of care. The health systems framework that some experts refer to is descriptive: it identifies the components of a health system. It is not an analytical framework that would allow researchers to estimate the effects of submitting the system to different stresses. The

| # | Intervention | Control |

| 1 | Supervision and monitoring with feedback | No supervision |

| 2 | Training of providers, cascade training package, one supervisory visit | Same, without supervisory visit |

| 3 | Two supervisory visits on adherence to guidelines and stock management | No supervision |

| 4 | Training on Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI), enhanced supervision, enhanced package of support | Training on IMCI, routine supervision, usual support package |

| 5 | Training of supervisors with Modified Matrix model or the Centre for Health and Social Studies (CHESS) model | Routine training of supervisors |

| 6 | Community leaders involvement in supervision | Routine supervision |

| 7 | Intensive monthly supervision | Routine supervision |

| 8 | Supervision with training and checklists | Routine supervision only |

| 9 | Quarterly supervision | Monthly supervision |

SOURCES: Bosch-Capblanch, 2015; Bosch-Capblanch et al., 2011.

lack of a clear analytic framework prevents any meaningful understanding of supervision or its effects. Bosch-Capblanch cited the development of such a framework as his group’s top priority; otherwise there is the risk of doing pointless research on outcomes that turn out to be irrelevant to the intervention.

This page intentionally left blank.