6

Cross-Cutting Approaches to Improve Quality

Key Points Made by Individual Speakers

- The evidence presented at the workshop was among the best in the field, but not as high-quality as anyone would like. (Heiby)

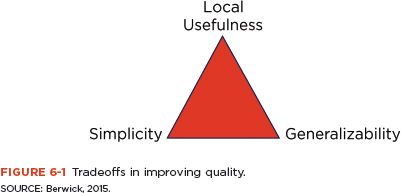

- Quality improvement work confronts tradeoffs among generalizability, simplicity, and local usefulness; though all three are desirable, it is not possible to have them all in one program. (Berwick)

- A “select and censure” approach to quality gives the field a bad name. A better method encourages innovation and continual improvement. (Berwick)

- Berwick saw evaluations and randomized trials as toxic and impeding progress. Randomization in particular he saw as a way to lose valuable contextual data. (Berwick)

At the start of the next session, meeting participants broke into three groups to discuss the practice, policy, and research of quality improvement. Afterward, a representative from each group summarized the main points of the discussions (see Boxes 6-1, 6-2, and 6-3).

PRACTICE TO IMPROVE QUALITY: HOW TO ACCELERATE PROGRESS?

Pierre Barker relayed the key themes from the discussion on practice. Members of the group were concerned that a failure to recognize successes

and learn from them has held back quality improvement as a field. They observed that people working in quality improvement lack a common forum in which to discuss their experiences. The paucity of collaboration can lead to practitioners wasting time and repeating mistakes. Many participants thought it would be valuable for quality improvement teams to have a way to learn from each other. One simple option would be writing up careful case studies of programs that work well. Another possibility, put forth by William Tierney, would be to establish a peer learning group to encourage collaboration. Setting up such a network would be a logistical challenge, but the challenge could be overcome with the proper support.

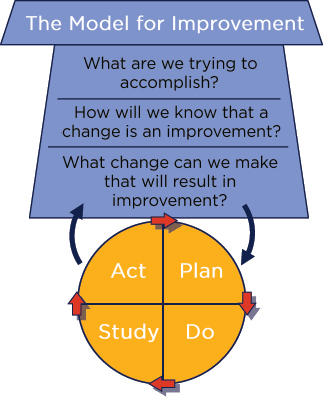

If there were a forum for collaboration, one of the first topics it might broach is motivation. Though almost everyone in the field uses plan-do-study-act cycles and collects data about their projects, understanding what motivates people to change is a serious question. There is growing interest among international organizations in giving incentives for quality improvement to providers and managers. Some participants welcomed this interest, but wondered how to select the best incentives. Without better understanding what motivates providers, it is hard to say what incentives to offer them.

Barker also described how the group had addressed questions of capacity building. As the meeting made clear, there are many different quality improvement strategies in use. Barker reported a common concern that quality improvement programs neglect patient-centeredness—respecting the patient’s needs and supporting them to make good decisions regarding their health. This problem could be corrected with more explicit attention to patient-centeredness in capacity building programs.

BOX 6-1

Main Points of Practice Discussiona

- People working in quality improvement have trouble recognizing their successes and learning from them. There is no clear forum for people working at different organizations to collaborate. One simple way to advance the field would be to give some attention to sharing detailed case studies of successful programs.

- International organizations are increasingly interested in using incentives to improve quality of care. This is a promising strategy, but depends on a better understanding of what motivates providers.

- Patient-centeredness can be neglected in quality improvement work, partly because patient empowerment and respectful treatment is a complicated skill to build. Quality improvement programs are good venues for capacity building, and building the ability of providers to give patient-centered services is essential.

a As summarized by breakout group rapporteur.

POLICY TO IMPROVE QUALITY: HOW TO CREATE AN ENVIRONMENT TO IMPROVE QUALITY?

Kedar Mate summarized the policy group’s discussion on how to create an environment conducive to improving quality of care. The group talked about policy implementation as a process that starts with evidence, which is then translated into a policy and implemented. Many participants thought that community stakeholders could be better included in this process. Quality improvement is often concerned with patient-centeredness, and Mate reported how some group members saw patient-centered policy as an outgrowth of involving patient groups and providers in policy making.

The group members recognized room for improvement in the way program staff interact with policy makers. Some suggested that, when involved with any quality program, whether implementing a collaborative or accrediting a clinic, the technical experts could include policy makers as part of the effort. This would ensure that policy makers are better informed of the quality strategies used in their countries and better able to translate quality improvement programs into policy.

Mate explained that policy makers need data to understand the effects of their efforts. He described this as a learning system, one that can be used to understand how well policies are working and how they might be adjusted. Members of the group acknowledged that it is difficult to say exactly what systems should be in place to support policy makers in translating evidence into policy; this could be an area for further research.

BOX 6-2

Main Points of Policy Discussiona

- Policy implementation is a cycle. Building evidence is the first step; evidence is then translated into policy.

- Policy should be made in close collaboration with communities. Patient groups are important stakeholders, as are providers.

- Policy makers need data and a good understanding of research to translate evidence to practice. This requires regular involvement with research and implementation staff.

- A learning system provides policy makers with regular feedback about quality improvement. Learning systems also hold promise for researchers as they attempt to understand why some policies succeed and others fail.

a As summarized by breakout group rapporteur.

RESEARCH TO IMPROVE QUALITY: HOW TO ADVANCE THE FIELD?

Margaret Kruk of the Harvard School of Public Health presented the main points from the research discussion. First, a number of group members were concerned that many thoughtful, evidence-based policies are never implemented. One useful goal for research would be to explain why some policies never come into force. Kruk advised that such research need not be heavily theoretical, but could be a practical comparison of settings where implementation succeeds with those where it fails.

The group members also discussed the importance of better measurement, both to the field of quality improvement and to health systems research more broadly. Many of the previous workshop speakers had emphasized the importance of process indicators in quality improvement. Kruk pointed out that there is good consensus on meaningful outcome measures in health, such as child mortality rates, but process indicators are less standardized. She explained how donor needs and competing project priorities have littered health systems research with hundreds, if not thousands, of indicators; researchers could do better work, and compare their results across studies, if there were a smaller, more tightly defined group of indicators.

Along the same lines, better guidelines on how to report the process of implementing quality improvement programs would help the researchers involved with program evaluation. Kruk described a common problem of evaluations in the peer-reviewed literature containing copious detail on everything except the meat of the project: the actual change implemented is not described. A good description of the process contributes to a better understanding of a program’s generalizability and external validity. In general, clearer guidelines on the best methods for evaluating quality improvement programs would be beneficial. Many participants in the research discussion were positive about using standardized patients to test providers, but acknowledged that observation may work better in some settings. In any case, the lack of gold standard research methods is holding back the field.

Improving measurement is linked to improving study designs. Kruk emphasized the value of prospective studies with evaluations incorporated into the design of the study from the start. Likewise, there was support for involving the evaluation staff from the start of a project to set up a rigorous evaluation. Several group members observed that study designs would be improved by applying a longer time frame; 6 months is too little time to observe a system and determine the effects of a change. Researchers would also do well to replicate the same study in different settings to observe the effects of contextual variables on outcomes and establish whether findings are generalizable.

Research on quality improvement requires investigators to first diagnose the problem in the health system and only then identify solutions. This ensures that the problem and the solution work at the same level. So, if a quality of care problem is caused by a policy or a regulation, then the solution would aim to correct that policy, rather than change the management of a particular clinic. Similarly, if the improvement method relies on management, it should first be clear that there are enough capable managers in the system to support the change. Kruk reported that the group members discussed the importance of establishing baseline performance before rushing into any improvement program because baseline data has a strong influence on possible effect sizes.

Members of the group were interested in having better data, especially from low-income countries. Some suggested that USAID could play a meaningful role by investing in a common information infrastructure in the poorest countries. Kruk commended the agency for insisting that data paid for by the taxpayers are a public good and should be publicly available. Similarly, many of the research group participants argued for better data sharing across projects. This would include more openness about projects that do not work, thereby allowing researchers to avoid repeating mistakes.

Lastly, the research discussion considered some of the obstacles in the organization of research at national and international levels. Some participants were concerned that the increasing interest in quality puts stress on the grassroots staff to do more without proper support from the government. They suggested that important decisions about how research is organized should be confronted at higher levels. This would give governments clear ideas about the responsibility of the data collectors and their authority over the data. For example, if projects are to be peer-reviewed, that arrangement would be formally recognized before the program begins.

BOX 6-3

Main Points of Research Discussiona

- Researchers would do well to explore what makes policy implementation a success or failure. Illustrative case studies may be a constructive way to do this.

- Quality of care research, and health systems research more broadly, has no consensus on a set of meaningful process indicators that could be reported across studies, allowing more direct comparisons of results.

- The rigor of quality research could be improved with more prospective studies, research over a longer time frame, and agreement on methodological gold standards.

- Clarity on the nature and potential causes of a quality problem should precede action on the solution. Establishing baseline performance is also an indispensable early step for researchers.

- A common data infrastructure would ease sharing of information across projects, enabling learning from other groups’ successes and failures.

- There is a need for more attention to governance of research, including the role of national and global stakeholders, researcher independence, peer review, and mechanisms for policy uptake.

a As summarized by breakout group rapporteur.

REACTIONS TO THE WORKSHOP

Heiby then shared his reflections on the workshop. He opened by noting that quality improvement in low- and middle-income countries is no longer in its infancy. Quality experts have collected considerable experience over the past 10 to 15 years. Heiby thanked the workshop participants for summarizing the experience that brought them to that point and identifying the problems that confront the field. Though the discussions had mostly looked at the evidence on quality improvement outcomes, he asked them to also consider how those results come to pass. One of the goals of quality improvement work is to build understanding as to what makes a program successful and how to replicate that success.

Heiby reiterated the opinion of many participants that the quality of the evidence presented at the workshop, though the best available in the field, was not as high as it could be. Most data came from program evaluations, a relatively new field. Heiby encouraged more research on program implementation—that is, on how programs work on the ground and how they can be improved. As an example, he described a large-scale quality improvement program in East Africa, which was faced with a decision about how to structure the supervision and coaching of its teams. One option was to place the central office, with its highly trained and intelligent staff, in charge; the alternative was to delegate responsibility to the provincial offices, where staff would be more familiar with local conditions. Through a field test comparison, they determined that the central office and provin-

cial offices had the same effect. But using teams from the latter cost only one-fifth of what it would to use the central teams.

Heiby used this example to illustrate the importance of examining the design of quality improvement programs, an area of research that warrants further study. He stressed the value of the depth of knowledge in quality improvement programming and encouraged the audience to unlock more transferable lessons from this data, adding that it would be unfair to suggest the field of quality improvement does not have data or understand the effectiveness of its interventions. Rather, the challenge is to improve the usefulness of the available data and evaluations and enhance monitoring and reporting.

Quality improvement tends to produce a good amount of information about effectiveness, but weaker data in other areas. Future projects could benefit from more attention to cost-effectiveness, non-clinical processes (e.g., human resources management), scalability, and sustainability (i.e., how to foster a culture of quality improvement in health organizations). Heiby cited the role of external advisors in quality programs as an area of particular concern for USAID, as programs that depend on foreign support are not sustainable. Program evaluations often blur the work of host country nationals and outside technical experts, to the detriment of the analysis.

Heiby shared his vision for the workshop’s outcomes, including briefing USAID’s senior management on the key messages. Because quality improvement is a relatively young field, there are opportunities to influence program design and capture the knowledge generated by quality programs. Heiby agreed that the thousands of professionals working in the field would benefit from a public clearinghouse on quality improvement programming and data. He saw the failure to share this data with people who would benefit as a profound waste of both existing and future resources because more time and money will be spent duplicating work.

Heiby closed by affirming a point made in the policy breakout discussion, that there is considerable room for improvement in how quality experts communicate their work to the public. Calling the discussion on research refreshing and overdue, he underlined the need to examine failures, not only successes, and to build research into quality improvement programs. Finally, he welcomed the suggestion that donors fund more prospective studies, as well as longer studies, on quality of care.

CLOSING REMARKS

Don Berwick, president emeritus and senior fellow at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, gave closing remarks for the workshop. Patrick Kelley, who directs the IOM Board on Global Health, briefly introduced the session, telling the audience how Berwick, along with Heiby and Sheila

Leatherman, had begun encouraging the IOM to work on quality of care in developing countries 12 years ago. Kelley reflected on how global health had changed during that time, especially with the billions of dollars spent through U.S. programs like PEPFAR and the President’s Malaria Initiative. The 2014 Ebola epidemic further underscored the value of developing strong health systems around the world. All of which, Kelley concluded, have shown the world that quality of care should be a priority for international action. But the question remains as to how quality can best be advanced in poor countries. The often-cited 2001 IOM report Crossing the Quality Chasm changed the way people think about quality of care in the United States, and Kelley described the challenges of adapting the earlier report to a global audience. Quality improvement in the United States makes certain assumptions—the stability and safety of the drug supply, for example—that do not always apply in low- and middle-income countries.

Kelley then introduced the IOM president Victor Dzau. Dzau added his reflections on the importance of strengthening systems for health, quality, and patient safety around the world. He observed that, for some time, the focus in global health has been to create better access to care and to keep services affordable. Only recently has the discussion turned to quality. It is not enough, he asserted, to invest money in access without paying attention to quality.

Dzau described how Crossing the Quality Chasm changed the practice of medicine in the United States, and he agreed that the dimensions of quality identified in that report (safety, effectiveness, timeliness, patient-centeredness, efficiency, equity) are universal. But he also echoed Kelley’s point that a larger set of quality issues is at work in low- and middle-income countries. He commended the workshop participants for their commitment to the field and expressed his support for a global quality of care project.

After an introduction by Dzau, Berwick began his presentation by thanking the participants, reiterating that such a meeting would not have been held 5 or 10 years earlier. The interest that has grown in the meantime is driven, he felt, by a desire to identify simple, generalizable methods that can be used to improve quality of care locally. Berwick described the tradeoffs among the three qualities shown in Figure 6-1, saying that it is not possible to find methods for quality improvement that meet all three conditions. When a solution is generalizable and simple, it is usually not useful locally and must be adapted. If something is generalizable and locally useful, then it will not be simple. Berwick encouraged the audience to keep this tension in the back of their minds.

Like other aspects of modern public policy, quality improvement rests on the assumption that inspection and attention will drive improvements. Berwick compared it to a Ghanaian proverb, “Weighing a pig doesn’t make it fatter.” He proposed that not only does measurement not cause improve-

FIGURE 6-1 Tradeoffs in improving quality.

SOURCE: Berwick, 2015.

ment, it can have a demoralizing effect on workers, the people who most need encouragement. Bill Scherkenbach of General Motors identified this problem in the 1960s, calling it a “cycle of fear” (Scherkenbach, 1991). When workers in a hospital system know that an inspection is coming, the anxiety interferes with their performance because invariably inspection results in the culling, or at least retraining, of some workers. The concept of removing poor performers from a system goes back to the 1920s: it was Henry Ford’s method of keeping production lines consistent. Berwick explained that modern quality improvement has moved beyond that in every field but health.

He conceded that systems do need to be accountable; especially in public or politically managed organizations, it is important to catch thieves and sack them. But he cautioned against a culture of inspection that poisons the well against quality improvement. At the same time, Berwick praised measurement as essential for learning. He explained that measurement can go down two paths. The first is the “select and censure” path that gives quality improvement a bad name; the second is measuring from a safe place, encouraging innovation and continual improvement while protecting employees and, in the case of health care, patients (Berwick et al., 2003).

In reflecting on the previous 2 days, Berwick concluded that quality defects are pervasive and problems with the health system drive these defects. As Barker had pointed out earlier, every system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets. So problems with quality of care are systems problems, particularly distressing ones in poor countries because that is where people can least afford poor quality. He asserted that improvement is often a nonlinear process in which effective learning requires both clear aims and iterative testing (see Figure 6-2). All six models that the workshop participants discussed depend on repeated testing to determine if the program is bringing the health system closer to a clearly articulated aim.

FIGURE 6-2 Combining three key questions with a plan-do-study-act cycle is a model for improvement.

SOURCE: Langley, G. J. 2009. The improvement guide: A practical approach to enhancing organizational performance. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. © John Wiley & Sons, Inc. As presented by Berwick on January 29, 2015.

While Berwick saw repeated testing and the emphasis on goals as positive influences on quality improvement, he described evaluation as toxic and actively impeding progress. First, he lamented the amount of time evaluation cycles require. Clinic managers do not have several years to wait before knowing how their changes are affecting patients; they need fast results. Along the same lines, he saw evaluations, particularly randomized trials, as being insensitive to local context. The goal of randomization is to remove the influence of confounders, which Berwick saw as a loss of valuable data. In quality improvement, the process by which some changes take root and others do not is as important as the final effects on health. Berwick suggested that both methodological rigor and the utility of evaluation would be enhanced with deeper understandings of local contexts and how they influence processes and outcomes.

Some of the meeting participants had reservations about placing too much emphasis on local context, however. They brought up the cost and

staffing constraints that get in the way of doing detailed implementation research or qualitative analysis. Jishnu Das pointed out that researchers are not inclined to work on large, messy public datasets for which there is little publication market, and major funders, including USAID, are not interested in funding large research projects. Some alternatives to traditional evaluations might give more attention to real-time data and feedback or use anthropology and ethnographic methods to understand how a system works.

An interest in local learning and context could help build will for a new global initiative in quality of care. Berwick spoke of how the IOM reports Crossing the Quality Chasm and To Err Is Human changed the way Americans think about medical error and quality of care. Although progress on the reports’ recommendations has been variable, the influence they had in terms of making managers aware of safety, timeliness, effectiveness, patient-centeredness, efficiency, and equity is undeniable. Outside of the United States, the reports’ effects have been less pronounced. Although Berwick noted progress in Denmark, Scotland, and Singapore, very little attention has been given to the topic in low- and middle-income countries. He asked for a well-considered statement about the nature and urgency of the gaps in the performance of health systems. This kind of information would call attention to the waste of resources that health markets are capable of and would motivate public interest in change.

Crossing the Quality Chasm identified a chasm between the care people have and what they could have. Berwick acknowledged that, while this gap still exists in developed countries, it is far worse in developing ones. He thought the time was right for more attention to quality problems in the parts of the world least able afford them and to encourage governments and donor organizations to action.

This page intentionally left blank.