Much has happened since 2007, when the District of Columbia gave control of its public schools to its mayor and made other governance changes through the Public Education Reform Amendment Act (PERAA). Then-Mayor Adrian Fenty acted promptly, filling the new office of chancellor of the District of Columbia Public Schools (DCPS) with an individual who used her authority and flexibility to make bold changes. The new leadership of DCPS and the other education agencies—the Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE), the D.C. State Board of Education, the Office of the Deputy Mayor for Education, and the Public Charter School Board (PCSB)—followed by implementing the changes called for by the law.

PERAA reflected high hopes that a significant shake-up of the public schools and a leader with a free hand would allow D.C. to break through decades of stagnation and poor outcomes for the most disadvantaged students. Recognizing that many people—parents, education officials, and teachers, as well as many other citizens—would be eager for reliable information about how the schools fared after the new law was implemented, the Council of the District of Columbia included in PERAA a requirement for an independent evaluation. This report describes the results of the second phase of that evaluation. It was carried out by the Committee for the Five-Year (2009-2013) Summative Evaluation of the District of Columbia Public Schools, appointed by the National Research Council of the National Academy of Sciences.

The first phase of the evaluation resulted in the report, A Plan for Evaluating the District of Columbia’s Public Schools (National Research

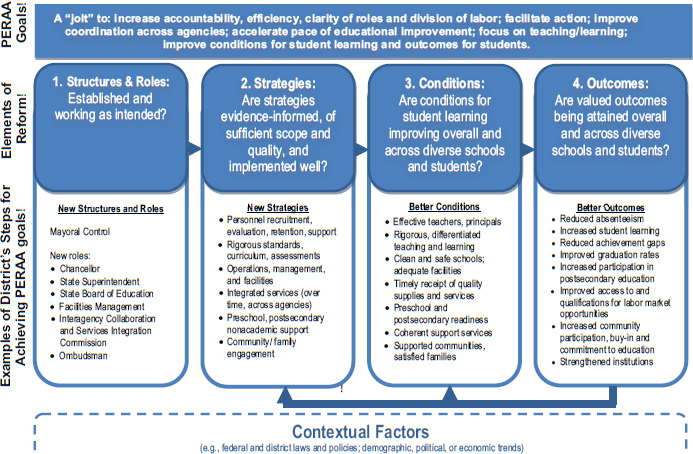

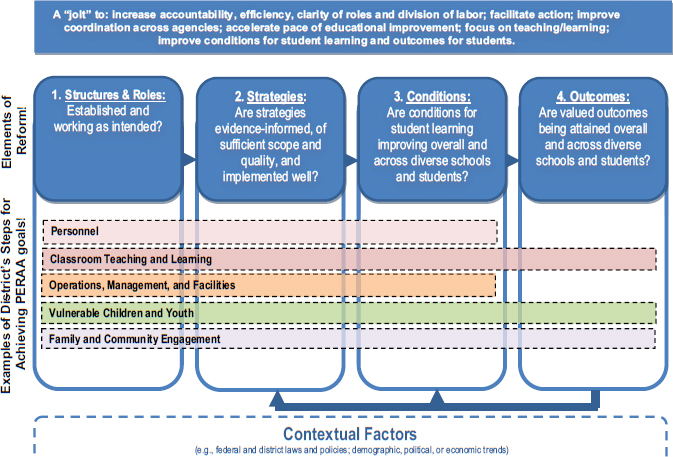

Council, 2011). That report (which we refer to as the Phase I report) recommended that the District of Columbia develop a plan for a sustainable, ongoing program of evaluation that yields reliable information, which can be used to support continued improvements to the school system: see Box 1-1. The report noted that there is no well-established model for ongoing evaluation of school districts, and that any district would benefit from a stable source of such information, whether it makes bold changes in governance or not.1 The report also provided a model for structuring the information an evaluation might collect: see Figures 1-1 and 1-2.2

The charge to the authors of this second report was to evaluate changes in the D.C. public schools during the period from 2009 to 2013, addressing the questions outlined in PERAA concerning the primary areas of school system responsibility. The complete charge is shown in Box 1-2.

In carrying out its charge, the committee was guided by the evaluation framework from the Phase I report and by specifications of the D.C. Council, which, with the concurrence and cooperation of the mayor, the chancellor of DCPS, and the State Superintendent of Education, funded this study. The sponsors requested that the evaluation address the questions in the framework covering four broad areas: see Box 1-3. Thus, for each of those areas, this evaluation addresses the following questions:

Structures and Roles: Were all structures and roles outlined in PERAA implemented and working as planned? Did “clearer functions and lines of authority” lead to better coordination and more efficient operations, which in turn promoted improvements in teaching and learning?”

Strategies: Did D.C. education officials “do what they said they would do, and how well did they do it”? Were the strategies in use developed out of best practices and executed well?

Conditions: Did conditions improve overall and across diverse schools and students?

________________

1D.C. public schools are now governed by 62 entities that function as districts, DCPS and the 61 entities that operate the charter schools, an aspect of school governance in the city that we discuss throughout the report.

2We refer readers to the earlier report for a more detailed description of the proposed evaluation model and other background and contextual information for this second phase of the evaluation.

BOX 1-1 Principal Recommendation from Phase 1 Report, A Plan for Evaluating the District of Columbia’s Public Schools

We recommend that the District of Columbia establish an evaluation program that includes long-term monitoring and public reporting of key indicators as well as a portfolio of in-depth studies of high-priority issues. The indicator system should provide long-term trend data to track how well the programs and structure of the city’s public schools are working, the quality and implementation of key strategies undertaken to improve education, the conditions for student learning, and the capacity of the system to attain valued outcomes. The in-depth studies should build on indicator data to answer specific questions about each of the primary aspects of public education for which the District is responsible: personnel (teachers, principals, and others); classroom teaching and learning; vulnerable children and youth; family and community engagement; and operations, management, and facilities.

SOURCE: National Research Council (2011, p. 5).

Outcomes: Were valued outcomes attained overall and were they equitably achieved for diverse schools and students?

This evaluation is different, in its broad scope, from the more targeted evaluations school districts often undertake. The committee could not look in depth at every issue of importance in the city’s schools—any of which might yield a book-length report—or conduct systematic audits of city offices and schools. Our charge required us instead to explore key questions in each broad area and develop reasonable conclusions about the progress of public education in the District of Columbia. For example, our charge included financial management. A thorough evaluation of budget expenditures and management would require resources and expertise that were beyond the committee’s scope but we focused on the transparency of the budgeting process, and on the distribution of other sorts of resources, such as learning opportunities and highly qualified teachers.

We examined the major goals the law was designed to achieve, some of the strategies that the city’s education leaders pursued to achieve those goals, and changes in learning conditions and outcomes since PERAA was enacted. However, given a complex and constantly changing system, we emphasize that it is not possible to trace any particular change in conditions or in outcomes for students directly to the effects of PERAA. Countless factors have affected developments in D.C.’s public schools since 2007. It is

FIGURE 1-1 A framework for evaluating DC public education under the Public Education Reform Amendment Act.

SOURCE: National Research Council (2011, p. 7).

FIGURE 1-2 Evaluation priorities in key areas of district responsibility.

SOURCE: National Research Council (2011, p. 8).

BOX 1-2

Committee Charge

The National Research Council (NRC) will establish an ad hoc committee to write a comprehensive 5-year summative evaluation report for Phase II of the initiative to evaluate the District of Columbia’s public schools. Consistent with the recommendations in the 2011 NRC report entitled A Plan for Evaluating the District of Columbia’s Public Schools, the NRC will commission a local research consortium, DC-EdCORE, to carry out a set of studies that will provide input to the summative evaluation report. The issuance of the 2011 report completed Phase I of the initiative, and DC-EdCORE was formed in response to the recommendations of that report. The new NRC committee will commission studies by DC-EdCORE and hold open meetings to discuss the results of DC-EdCORE studies and other relevant research. The committee will write a consensus evaluation report that describes changes in the public schools during the period from 2009 to 2013 and also addresses the questions outlined in the PERAA legislation about effects on business practices; human resources operations and human capital strategies; academic plans; and student achievement.

BOX 1-3

The Four Subject Areas to Be Covered by the Evaluation

- Business practices and strategies: including organizational structure and roles, financial management, operations management, facilities and maintenance; resource allocations; public accountability, interagency collaboration, stakeholder engagement and responsiveness.

- Human resources operations and human capital strategies: including the number of and percentage of highly qualified teachers under No Child Left Behind and IMPACT, retention rate for effective teachers, and the schools and wards served by effective teachers. The length of time principals and administrators serve, types of leadership strategies used, and responsibilities of central office versus school-level leadership.

- Academic plans: including integration of curriculum and program-specific focus into schools, grade progression, and credit accumulation.

- Student achievement: including a detailed description of student achievement that includes academic growth, proficiency, and nonacademic values.

not possible to compare what has happened in the schools with what would have happened had PERAA not changed their governance. Nor is it possible to disentangle the changes brought about by PERAA from the many other developments and reforms that occurred at the same time that PERAA was being implemented. Instead, we conducted a top-level examination of what is working well and which areas need additional attention, and we offer questions for the city to consider.

The Committee for the Five-Year (2009-2013) Summative Evaluation of the District of Columbia Public Schools was composed of 10 individuals with expertise in relevant areas, including program evaluation, school governance and organization, urban education reform, teaching and learning, teacher training and evaluation, and student achievement and preparedness. Their backgrounds and experience include district governance, policy making, teaching, and research. None of the committee members resided in the District of Columbia or had any direct links with the D.C. government.

Data Sources

The committee held six meetings in 2013 and 2014. Four of those meetings included public sessions at which the committee heard from many individuals who came to share their perspectives on public schooling in the city, describe challenges and problems they had observed, and answer the committee’s questions about their experiences and district functions. The committee also collected and synthesized a wide range of other information, including the results of complex statistical analyses, information obtained from D.C. agencies, external analyses, and structured interviews. Our use of these sources varies by chapter, depending on the questions that the chapter addresses and the nature of the available information. In each of the following chapters, we discuss the specific information on which our analyses are based.

When drawing conclusions from the evidence, we gave precedence to results from empirical analyses published in peer-reviewed journals. However, as is often the case with evaluations, reports of this type that addressed the D.C. schools were scarce. To compensate for this limitation, we placed the greatest weight on evidence that could be corroborated through multiple sources.

D.C. Agencies and Websites

The committee was highly dependent on information and data either provided by city agencies in response to our requests or available on their public websites. Appendix A summarizes the requests we made to education agencies and the materials we received. We sent individual requests to the offices that were most likely to hold particular information, and we submitted all of the requests as a package to the heads of all relevant agencies, along with a request for their support in providing the information. All the written materials the committee received from city agencies are available in the public access file of the National Academy of Sciences.

Overall, we were hampered by difficulty in obtaining some of the information we sought from the city. As Appendix A shows, many of our requests for information from the education agencies were not filled for more than a year, and some were never filled. The D.C. government has seen considerable staff turnover in the years since PERAA was passed, and several current staff members had difficulties locating data and records that predated their tenure. We are grateful for the efforts of many city employees who assisted us, but we note the lack of a central source for most information and of personnel available to assist us in coordinating the information we sought.

It was surprisingly difficult to obtain even the data needed to present a clear picture of some basic trends in the years since PERAA was enacted. Though data, reports, and other materials are posted across several websites, there is no one resource among the city’s many websites where complete information about the entire jurisdiction is posted.

The DCPS website provides summary data characterizing its own students, schools, and educators (these data do not cover the charter schools), but as we discuss in Chapter 3, neither the home page of the OSSE nor a new website called LearnDC, which provides some data for DCPS and the charter schools, guides the user to summative data about all public school students and schools.3 The website of the PCSB provides some useful information about the charter schools, but it offers little summative data about the students, schools, and educators in that sector.4 In addition, some of the data we received from the agencies were difficult to reconcile.

________________

3See http://dcps.dc.gov/DCPS/About+DCPS/Who+We+Are [May 2015]; http://dcps.dc.gov/DCPS/About+DCPS/DCPS+Data [May 2015]; http://osse.dc.gov/service/data [May 2015]; and http://www.learndc.org/ [April 2015].

4See http://www.dcpcsb.org/resource-hub [April 2015].

Commissioned Analyses

The committee also had access to data analyses conducted by an independent group, the Education Consortium on Research and Evaluation (DC-EdCORE) The Phase I report (National Research Council, 2011) recommended that the city support the development of an independent research consortium that could carry out ongoing data collection and analysis to use in evaluating the education system. George Washington University sponsored the development of DC-EdCORE as a first step in establishing such a consortium.

The National Academy of Sciences’ contract with the city for this evaluation included a subcontract for DC-EdCORE to collect and analyze quantitative and qualitative data on particular topics of interest to the city: see Box 1-4. DC-EdCORE produced five reports that address specific questions related to those topics; those reports were submitted to the city before this report was published. We have drawn on data in these reports that were relevant to our evaluation questions, particularly in Chapters 4 and 6 (Education Consortium for Research and Evaluation, 2013a, 2013b, 2014a, 2014b, 2014c, 2014d).

BOX 1-4

The Role and Products of DC-EdCORE

Because the committee was not in a position to conduct primary data collection and analysis, the design for the evaluation included subcontracts for a new entity, DC-EdCORE, to perform this work on selected topics and prepare reports on its findings. DC-EdCORE is entirely independent of the National Research Council and the committee. Other research organizations, including the American Institutes for Research, Mathematica, and Policy Studies Associates, collaborated with DC-EdCORE to carry out this work.

EdCORE produced five annual reports, plus one supplement. The Office of the D.C. Auditor determined the scope of these reports based on the contents of PERAA. Members of the EdCORE team attended meetings of our committee to discuss the development of its reports, and it made drafts of the reports available to the committee for comment, but the reports are solely the product of EdCORE. The committee notes throughout this report when it used information from the DC-EdCORE reports.

The DC-EdCORE reports are available on the website of the D.C. Auditor, at http://dcauditor.org/reports [May 2015]. To find a report, it is necessary to search the report list by year. Below is a synopsis of the contents of the five reports.

Report No. 1: School Year 2010-2011 (submitted July 15, 2013): Snapshot descriptions of events and indicators associated with three of the primary evaluation topics (business practices, human resources, and academic plans) as of school year 2010-2011, plus description of selected indicators of student achievement between 2006-2007 and 2010-2011 (Education Consortium for Research and Evaluation, 2013a).

Report No. 2: School Year 2011-2012 (submitted September 6, 2013): Snapshot descriptions of events and indicators associated with two of the primary evaluation topics (business practices, human resources) as of school year 2011-2012; description of academic plans for years 2006-2007 through 2011-2012; and description of selected indicators of student achievement between 2006-2007 and 2011-2012 (Education Consortium for Research and Evaluation, 2013b).

Report No. 3: Trends in Teacher Effectiveness in the District of Columbia Public Schools (submitted August 22, 2014): Presentation of data on DCPS teacher effectiveness, as measured by IMPACT, and teacher retention, and data on trends in teacher effectiveness by ward and socioeconomic statusa (Education Consortium for Research and Evaluation, 2014a).

The Impact of Replacing Principals on Student Achievement in DC Public Schools (DCPS) (submitted December 3, 2014; supplement to the third report): Analysis of changes in student achievement that occurred when principals who left DCPS schools were replaced, for school years 2007-2008 through 2010-2011 (Education Consortium for Research and Evaluation, 2014b).

Report No. 4: A Closer Look at Student Achievement Trends in the District of Columbia (submitted September 5, 2014): Analysis of trends in student achievement in D.C. public schools between 2006-2007 and 2012-2013 (Education Consortium for Research and Evaluation, 2014c).

Report No. 5: Community and Family Engagement in DC Public Education: Officials’ Reports and Stakeholders’ Perceptions (submitted November 5, 2015): Summary of findings from interviews with city education officials and community members on the subject of city efforts to improve public engagement (Education Consortium for Research and Evaluation, 2014d).

________________

a The committee noted the potential conflict of interest that arose when Mathematica was asked to conduct the analyses related to IMPACT because that organization had played a role in designing the system, and we called that issue to the attention of EdCORE. The committee had the opportunity to review and comment on the research plan for the task Mathematica was given, as well as a rough draft of the report.

In addition, the committee commissioned three papers to explore several topics in greater depth. One paper (Henig, 2014) analyzed reforms in other urban districts that provide useful comparisons with what D.C. has done. The other two papers addressed aspects of the new teacher evaluation system, IMPACT, that was one of the first improvement strategies adopted by DCPS after PERAA: one (Koedel, 2014) explored technical questions associated with value-added modeling (used in the calculation of quantitative ratings of teachers used in the evaluation), and the other (Gitomer et al., 2014) examined the system as a whole in the context of similar efforts around the country.

Interviews

To understand D.C.’s responses to PERAA and the structure and functioning of the city’s education agencies, the committee conducted 15 structured interviews in 2014 with leaders and staff in each of the entities with a role in school governance (see Appendix B for a sample interview protocol):

- the D.C. Council,

- the District of Columbia Public Schools,

- the Office of the Deputy Mayor for Education,

- the Office of the State Superintendent of Education,

- the Public Charter School Board, and

- the State Board of Education.

These interviews included many of the officials who shaped major policy and programmatic decisions under PERAA. A main focus of the interviews was to learn how D.C. officials and staff understood and interpreted their agency’s mission and their reasons for making the programmatic choices they made.

The committee was not able to expand its interviews to include teachers, principals, parents, or students. We were able to talk with 3 instructional superintendents, each of whom oversees a cluster of approximately 12 schools. In addition, teachers and parents shared their experiences and perspectives at public meetings held by the committee. Community leaders, advocates, and others interested in public education issues also presented their views during open sessions of the committee’s meetings.

Throughout the course of the study, committee members and staff also spoke with staff members in city offices to ask specific questions and request materials, as well as with city residents who have specialized knowledge of the areas we examined. These conversations were not structured interviews; they were generally used to clarify or elaborate a particular topic that the committee was examining.

We are committed to protecting the privacy of everyone who spoke with us. We use information from the interviews to supplement and illuminate the other evidence we present in the report; that information is anonymous but when we present a specific quote or refer to an individual, we describe the individual’s general role (e.g., city official, DCPS staff).

Other Reports and Analyses

The committee also examined relevant research and policy analyses. Although peer-reviewed research specifically on D.C.’s education system was scarce, the committee drew on scholarly literature related to the topics we were examining (e.g., teacher evaluation, mayoral control). In addition, we obtained information from reports prepared by research and policy organizations about specific aspects of education in the District of Columbia (e.g., a report on the adequacy of funding for D.C.’s public schools, an analysis of special education issues in D.C.).

This evaluation is a synthesis of available information about the progress of the schools that covers the years since PERAA was enacted. The structure of the report follows the primary questions we were charged with addressing, which in turn were based on the model for evaluation described in the Phase I report (see Figures 1-1 and 1-2, above).5Chapter 2 gives an overview of the context for this evaluation, including a brief discussion of the basic features of the school district as it was when PERAA became law and as it is now and then a detailed discussion of mayoral control as a reform strategy and as it developed in D.C.

Chapters 3 through 6 address the specific questions in our charge: Chapter 3 addresses the questions about structures and roles, discussing the way in which the city carried out the key provisions of PERAA and the current governance structure. Chapter 4 focuses on the strategy DCPS adopted with respect to a key goal, improving human resources, which is also one of the key topics in our charge. Chapter 5 discusses the current conditions for learning across the system, and Chapter 6 discusses outcomes for students. In these chapters, we review specific PERAA goals, assess some of the major actions the agencies have taken, and explore available evidence about how circumstances and outcomes may have changed.

The final chapter pulls this information together to provide answers to basic questions about which efforts seem to be working well 7 years after

____________________

5Our charge lists five questions, which are a reframing of the four questions in the evaluation model.

PERAA’s adoption and which need additional attention. We offer recommendations with respect to both the progress of the schools under PERAA and the city’s ongoing data collection and evaluation needs.

This evaluation addresses all public schools in the District of Columbia, both DCPS and the public charter schools. We discuss data for DCPS and the charter sector whenever it is available, but significantly less information was available about the charter schools and students than those in DCPS. Moreover, the shifting populations of the two sectors made it difficult to compare trend data. Because one of PERAA’s major provisions was to create a chancellor for DCPS, it is also possible that DCPS students, schools, and staff have been more directly affected by PERAA than their counterparts in the charter sector. As a result, some of our discussions focus more on DCPS than on charter schools; however, it is important to keep in mind that the students who attend charter schools are an equally important component of the city’s education system.

We hope this report will be useful to the city not only for the conclusions we have drawn and the recommendations we make, but also for the context and analysis the committee provides. Reliable evaluation is essential to improvement, and all states and school districts confront similar challenges in finding ways to sustain the needed data collection and analysis. We therefore hope that this report will also be valuable beyond the District of Columbia, to policy makers and others concerned with the challenges of school improvement.