3

State of the Science: Treatment Development

Highlights

- Cognition should be a target for treatment in depression (Sahakian).

- Studies of the effectiveness of pharmacologic treatment of depression have failed to show consistent benefits for cognition, in part because of variability in trial design and assessments (Keefe).

- Pharmacological treatment of depression has only small beneficial effects on certain aspects of cognition, such as verbal and visual memory, and may even worsen others such as processing speed (Keefe).

- Innovative pharmacotherapy approaches may improve therapy for cognitive dysfunction in depression (Harmer, Sahakian).

- Non-invasive neuromodulation has shown some effectiveness for the treatment of depression, but effects on cognition are unclear (Etkin, Pizzagalli).

- Very few studies have assessed the effects of psychotherapy, cognitive behavior therapy, or cognitive remediation on cognition in depression (Bowie, Pizzagalli).

- Effective treatment of cognitive dysfunction in depression will likely require a multimodal approach and stratification of patients to enable more individualized therapy (Areán, Bowie, Pizzagalli, Sahakian).

NOTE: These points were made by the individual speakers identified above; they are not intended to reflect a consensus among workshop participants.

As outlined earlier, depression is associated with neuropsychological dysfunction across multiple domains, including executive function, attention, memory, and psychomotor speed. Although there are many approaches to target cognition in depression—including both pharmacological and nonpharmacological approaches—developing new treatments has proved challenging. Amit Etkin, assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford University, framed the challenges with three key questions:

- Does treating depression improve cognition?

- How do we know if cognition is improved?

- What would a cognition-improving treatment target look like?

Antidepressant medications developed in the 1950s have been largely supplanted by second generation antidepressants that modulate the monoamine neurotransmitter system by increasing the availability of serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine. However, even these newer drugs have limited efficacy, with only modest superiority over placebo in most clinical trials (Undurraga and Baldessarini, 2012). Moreover, no drugs have been approved by FDA or the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for the treatment of cognitive impairment in MDD, although many clinical studies of antidepressants have included cognitive endpoints and have shown either improvements in cognition or treatment-associated cognitive impairment as an adverse event (Keefe et al., 2014). Because mood symptoms and cognition track with one another in patients with depression, particularly during treatment, it has proved challenging to design studies that assess cognition independently from changes in mood, said Richard Keefe, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Duke University. These challenges relate to selection of the appropriate study design, patient population, and assessment tools, as well as the method of data analysis. Keefe discussed a meta-analysis of the literature that he and his colleagues conducted to assess the effects of antidepressant monotherapy and augmentation therapy (i.e., adding a second drug to existing antidepressant therapy) on cognition (Keefe et al., 2014). Forty-three studies were included in this analysis, yet they varied in terms of the study design (e.g., placebo controlled versus active comparator versus open label), study participants, sample size in the individual study, study duration,

agents tested, and primary and secondary outcomes. Most of these studies had cognition as a primary outcome, although some had it as a secondary outcome or safety report. Most studies also assessed cognitive function in the presence of mild to severe depressive symptoms, which made it difficult to determine whether treatment directly affected cognition or if effects were secondary to changes in mood. Furthermore, the studies used a wide variety of tests across multiple domains, including processing speed, psychomotor function, attention, verbal learning and memory, verbal fluency, visuospatial awareness, and executive function. The categorization of an individual test to a domain varied from study to study, said Keefe, reflecting the lack of consensus across the field. All of this variability made it challenging to compare studies, he said.

Most of the studies demonstrated at least some statistically significant cognitive benefit, particularly in the domains of verbal memory, working memory, and processing speed. However, the effects were small, and for only 12 percent of the cognitive measures did the analyses favor active treatment over placebo; 4 percent percent favored placebo. One question Keefe asked is whether these results exceed “the file drawer problem,” by which investigators tend to publish positive results, but not negative results. He noted that all cognitive tests were included in the analysis, with no attempt to support a specific hypothesis, such as that certain domains would be affected more than others. Nor was the question of clinical meaningfulness addressed in this analysis. Nonetheless, some tentative trends emerged: Monotherapy resulted in slight improvements in verbal memory, while augmentation therapy resulted in improvements in visual memory, verbal memory, processing speed, executive function, and cognitive control.

Keefe also noted that all of these studies looked only at cold cognition because the literature on hot cognition is new and sparse. However, it may be that hitting hot cognition is necessary to improve cognition as well as to alleviate depressive symptoms and experiences. He also mentioned another study of lisdexamfetamine, which included self-reports and informant reports as well as a cognitive battery as outcome measures. Interestingly, in this study, the computerized battery did not demonstrate significant improvement with the active compound compared to placebo, although both self- and informant reports did (Madhoo et al., 2014).

With regard to determining whether a drug affects cognition directly or indirectly, Keefe described a recent study comparing vortioxetine and duloxetine using both objective and subjective assessments: the digit

symbol substitution test (DSST) to measure a direct effect on cognition, the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) to assess improvement in depressive symptoms that could directly affect cognition, and improvement on a functional capacity measure, the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), performance-based skills assessment (UPSA). Both drugs improve cognition, as has been demonstrated in other trials, but path analysis in this trial indicated that vortioxetine does so through a direct effect of the treatment, whereas the cognitive improvement from duloxetine is mediated by a consequence of improvements in depressive symptoms (Katona et al., 2012; Mahableshwarkar et al., 2015; Raskin et al., 2007).

Keefe concluded that no firm conclusions can be drawn about the effects of antidepressants on cognition using pharmacotherapy. Although tentative trends toward cognitive improvements from both monotherapy and augmentation therapy emerged, the studies were limited by a high degree of variability in study design, numbers of patients enrolled, duration of treatment, outcome measures, and heterogeneity among patients (e.g., comorbidities and the severity of depression). He further noted that while antidepressants may have very small beneficial effects on some aspects of cognition such as verbal and visual memory, they may worsen others, such as processing speed. These effects may be limited only to certain subgroups of patients, he added.

Barbara Sahakian and others called for innovation in the development of new treatments. For example, cognitive-enhancing drugs represent a class of drugs that may be beneficial in patients with depression. Modafanil, a putative cognitive-enhancing drug, has been shown to enhance working memory and task-related motivation in healthy volunteers, and emotional processing (hot cognition) in patients with first episode psychosis, according to Sahakian (Muller et al., 2013; Scoriels et al., 2012). A meta-analysis demonstrated that as an augmentation therapy, modafanil improved overall depression scores, remission rates, and fatigue symptoms (Goss et al., 2013). Sahakian commented that the multimodal drug vortioxetine has been reported to improve performance on tests of cold cognition (McIntyre et al., 2014). Sahakian also advocated for further research on the use of fast-acting antidepressants, such as ketamine, a glutamate NMDA receptor agonist that induces synaptogenesis (Duman and Aghajanian, 2012). Indeed, studies suggest that a single dose of intravenous ketamine significantly improves symptoms of depression within 2 hours (Zarate et al., 2006). Other novel drugs are also in development. For example, Catherine Harmer is using experimental

medicine approaches (discussed in Chapter 4) in studies with Eli Lilly on the development of a nociceptin receptor agonist for the treatment of depression.

Based on findings discussed earlier about the neurobiological basis of cognitive dysfunction in depression, a variety of nonpharmacologic treatments are being considered as potential treatments, including transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), especially repetitive TMS (rTMS); transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS); psychotherapy; and cognitive remediation.

Neuromodulation with rTMS or tDCS provides a non-invasive way to stimulate regions of the brain that function abnormally in depressed patients. However, although many studies have demonstrated effectiveness in treating depression, their effects on cognition remain unclear. TMS delivers stimulation via a coil placed over the DLPFC. Etkin said TMS appears to normalize connectivity between brain networks involved in cognition and emotional regulation, that is, the left DLPFC and the DMN, although the specific targets within these networks have yet to be elucidated (Liston et al., 2014). Neuromodulation with tDCS uses a different approach, applying a very low-intensity direct current over the scalp between two electrodes, which generates a current flow that can elicit cortical excitability changes (Demirtas-Tatlidede et al., 2013; Nitsche et al., 2003). Again, the neurophysiologic response to this excitation is unclear, although some studies have suggested that it may modulate synaptic plasticity (Marquez-Ruiz et al., 2012).

Diego Pizzagalli discussed many studies of TMS. In one review of 16 randomized, sham-controlled studies, only 3 showed beneficial effects on executive function (Tortella et al., 2014). In another review of 13 sham-controlled studies, 5 showed significant differences in measures of cognitive function (Demirtas-Tatlidede et al., 2013). While methodological differences between the studies may account for these varying results, another possibility is that sham TMS itself produces an effect, or that very strong placebo effects mask the effectiveness of the approach, said Pizzagalli. Sham-controlled studies of tDCS have produced somewhat more promising results in terms of beneficial effects on some domains of cognitive function, such as working memory and attention (Demirtas-Tatlidede et al., 2013; Mondino et al., 2014; Tortella et al., 2014).

Another factor may help to explain the variable results using neurostimulation, said Etkin. Nearly all data available on rTMS for depression targets the left DLPFC with high-frequency stimulation; however, the literature supporting this as the best target in depression is weak. The field has settled on this target without, for example, rigorously testing whether left or right DLPFC high frequency rTMS is better. For post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), most rTMS studies have targeted the right side, and some of these studies have shown cognitive improvement, he said. He also noted that other brain regions, such as the basal fore-brain or the amygdala, might also be interesting targets; however, tools to reach those targets are not available.

PSYCHOTHERAPY AND COGNITIVE REMEDIATION

Very few studies have tested the effects of psychotherapy or cognitive behavioral therapy on cognition in depression, said Pizzagalli. One study he cited found that a combination of psychodynamic therapy plus fluoxetine was superior to either one alone (Bastos et al., 2013). A new type of treatment called metacognitive therapy, which targets perseverative thinking and includes an attentional training component, has shown some promise in improving spatial working memory and executive functioning in patients with depression. However, there were substantial individual differences among the 48 subjects tested, and changes in cognition did not correlate with changes in mood symptoms (Groves et al., 2015).

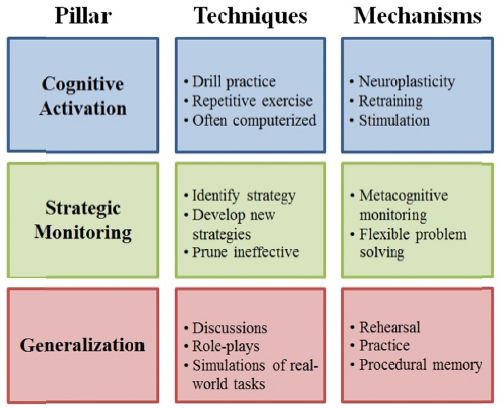

Another approach, cognitive remediation, has proved to be both efficacious and effective in treating schizophrenia, yet has been applied infrequently and with mixed results for the treatment of depression, according to Christopher Bowie, clinical psychologist and associate professor at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, Canada (McGurk et al., 2007). Cognitive activation—such as the computerized drill and practice puzzles and games popularized by Lumosity and other companies—represents only one pillar of cognitive remediation. The other two pillars are strategic monitoring, which involves helping people to identify the strategies they use to solve problems, and generalization, often referred to as bridging, which aims to help people envision or practice how they would use their improved cognitive skills in an everyday environment. Bowie said that for people with depression, strategic monitoring and generalization represent perhaps the most important aspects of cognitive

remediation because patients lose their incentive to participate if they are unable to see benefits in their everyday lives (see Figure 3-1).

Early studies of cognitive remediation in depression have, for the most part, failed to address all three pillars, but have involved computerized cognitive training in small, minimally controlled studies. Although patients saw improvements in cognitive measures, everyday behaviors remained relatively unchanged (Alvarez et al., 2008; Elgamal et al., 2007; Meusel et al., 2013; Morimoto et al., 2014; Naismith et al., 2010). Bowie’s group conducted a study that used all three pillars of cognitive remediation in a group of patients with treatment-resistant depression.

FIGURE 3-1 The three pillars of cognitive remediation.

SOURCE: Presented by Christopher Bowie at the IOM Workshop on Enabling Discovery, Development, and Translation of Treatments for Cognitive Dysfunction in Depression, February 24, 2015.

Following 90-minute sessions that included computer-based exercises and working with a therapist for 10 weeks, patients were given homework: two 20-minute online sessions per day with the same computerized

tasks they had done with the therapist as well as taking notes about their strategies for using cognitive skills in their everyday life (Bowie et al., 2013). Large effects were observed on cognitive tests for learning and memory, attention, and information-processing speed, but not for executive function, and there were no improvements in self-rated everyday behavior. These results prompted the researchers to explore how to focus cognitive remediation approaches on acquisition of everyday skills and behaviors and how to help people understand how to use new-found abilities in everyday life.

In response to the lack of improvements in self-rated behavior seen in these studies, Bowie and colleagues developed an “Action-Based Cognitive Remediation Program,” which takes a holistic behavioral therapy approach. The program aims to help patients develop and prune strategies so they can use their cognitive skills optimally to solve problems. It teaches skills procedurally using a computer-based cognitive training program and then immediately puts those skills to use in simulated real-world environments. Participants showed robust and durable improvements in verbal memory, verbal fluency, and functional capacity, said Bowie, as well as statistically significant increases in the number of people working 3 to 6 months post-treatment, and less job stress among those who were already working.

COMBINING AND PERSONALIZING THERAPIES

The choice of optimal treatment for an individual patient varies depending on a number of factors, many of which have yet to be clearly defined. Sahakian said cognitive treatments are important for top-down control, while pharmacologic interventions are important for treating negative affective bias and reinstating positive attitudes (Roiser et al., 2012). Multiple treatments may be needed, including use of pharmacologic treatments to put people into the right state so they can learn and change the way they are thinking using cognitive-behavioral approaches. Such approaches also may enable patients to identify when their mood is being dysregulated. Bowie agreed that combination treatments may be needed to synergistically improve both cognition and function. He also suggested that the different treatments may have variable levels of effectiveness at different stages of disease. For example, those with depression but very mild cognitive impairment may respond differently to a treatment than the typical population recruited into research studies.

Identifying people with certain neural abnormalities is another approach to personalizing treatment, said Pizzagalli. For example, individuals who have difficulty switching off the DMN and engaging task-positive networks might benefit from neurostimulation or cognitive remediation. Prescreening and stratifying patients may be the way forward to deal with the problem of heterogeneity, he said. However, stratifying patients into different subgroups based on symptomatology, neurobiology, and biomarkers remains a substantial challenge. Etkin concurred, adding that while many participants supported the idea of subtyping, it points to the need for many more targets and tools to match subgroups to mechanisms to interventions.

Patricia Areán, then professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco, School of Medicine, suggested that cognitive responses to treatment may help identify subgroups of depression as well as appropriate therapeutic approaches. For example, behavioral problem-solving approaches may be particularly efficacious in patients with depression and executive dysfunction.

This page intentionally left blank.