6

Lessons Learned from the Schizophrenia Field

Highlights

- As in depression, cognitive impairment is a core feature of schizophrenia. Lessons learned from the schizophrenia field thus have relevance for the treatment of cognitive dysfunction in depression (Green, Harvey).

- Many of the same strategies for assessing cognition and function in schizophrenia can be used successfully in depression, although patients differ considerably from a functional standpoint (Harvey).

- Several workshop participants identified concerns about developing a composite cognitive battery for cognition in depression similar to that developed through a consensus process for schizophrenia (Fava, Keefe, Sahakian).

NOTE: These points were made by the individual speakers identified above; they are not intended to reflect a consensus among workshop participants.

As in depression, cognitive impairment is a core feature of schizophrenia and a predictor of poor functional outcome (Green, 1996; Heinrichs and Zakzanis, 1998). According to Philip Harvey, much of what we know about cognition in schizophrenia may apply to studies of cognition in depression, particularly as the field grapples with issues of assessment. Just as cognitive assessments needed to be tailored for use in schizophrenia, they need to also be tailored for mood disorders, said Harvey.

The schizophrenia field tackled the issue of assessment as part of the MATRICS initiative, which was established by NIMH in 2003 in response to the recognition that antipsychotic medications for schizophrenia do not improve cognition. Michael Green said the initiative was undertaken to address the bottlenecks that had slowed the development of treatments targeting cognition in schizophrenia, namely (1) a lack of consensus regarding cognitive targets, (2) lack of widely accepted endpoints, (3) ambiguity regarding the optimal designs for clinical studies, and (4) an unclear path to FDA approval and labeling.

While the steps undertaken by MATRICS to address these challenges may offer lessons for the depression field, some workshop participants expressed concerns about strictly following the MATRICS model. For example, the initiative developed a consensus cognitive battery (the MCCB) using the RAND panel method, which included input from individuals from academia, NIMH, industry, FDA, and consumers (Buchanan et al., 2005). However, several workshop participants, including Maurizio Fava, suggested that the depression field may not yet be ready to reach consensus on outcome assessments.

One of the first challenges encountered by the MATRICS team was the problem of pseudo-specificity or, for a drug treatment, an artificially narrow claim of a drug effect, Green said. As mentioned in the previous chapter, for the treatment of cognitive dysfunction in depression, pseudo-specificity is likely to be a major regulatory concern and design challenge, several workshop participants said. For example, regulators are likely to reject a claim that a drug improves cognition in depression if it actually works in general for cognition, or if depressive mood is driving poor cognition. Similarly, if cognitive impairment in schizophrenia is driven by some other feature of the illness, such as psychosis, an antipsychotic treatment would be considered pseudo-specific for cognition in schizophrenia. Pseudo-specificity was discussed in more detail in Chapter 5.

MATRICS addressed this challenge by presenting data showing that the pattern of neuropsychological cognitive deficit scores in schizophrenia differs from the pattern in Alzheimer’s disease, that is, cognition in schizophrenia was not pseudo-specific. They later reached consensus that to isolate a change in cognitive function from a change in other clinical

features, studies should restrict symptom severity in subjects prior to randomization and select clinically stable patients (Buchanan et al., 2005).

Harvey said studies of schizophrenia may help to inform efforts to assess cognition and function in depression. Indeed, Harvey cited the conclusions of a bipolar consensus group that cold cognition can be assessed with the same strategies in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, and a study by Harvey and colleagues showed that cold cognitive domains were similar in both schizophrenia and depressed patients who were stabilized after a first episode of their illness (Harvey et al., 2015; Reichenberg et al., 2009). However, these patients differed considerably from a functional standpoint, said Harvey.

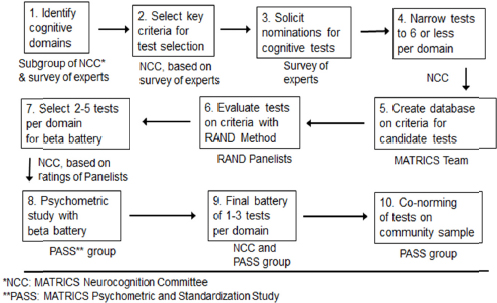

Also, as mentioned in Chapter 4, many studies of tools for assessing cognition in depression compared patients with schizophrenia to those with mood disorders, using a combination of subjective and objective measures aimed at both cognition and everyday function. One of the most common objective tests used in these studies is the MCCB. In developing this tool, MATRICS employed a multistep process (see Figure 6-1), which began by identifying the relevant cognitive domains to be tested, selecting the criteria for appropriate tests of those domains, soliciting nominations for tests, narrowing the number of tests to six or fewer per domain, creating a database and evaluating the tests using the criteria defined earlier, selecting two to five tests per domain for the “beta” battery, conducting a psychometric study with this battery, finalizing the battery, and then co-norming the tests of a community sample.

According to Green, selecting the criteria for test selection and collecting the data to evaluate the tests proved to be problematic in that it required an inherent trade-off between balancing the need for data from existing studies and the desire to find novel but more sensitive tests that might provide more power for clinical trials. To address these challenges, a separate initiative, CNTRICS (Cognitive Neuroscience Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia), was launched to move the field beyond standard tasks to those that reflect the state of the art in cognitive neuroscience.

FIGURE 6-1 Steps to MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery.

SOURCE: Adapted from Green et al. (2004, fig. 1). Presented by Michael Green at the IOM Workshop on Enabling Discovery, Development, and Translation of Treatments for Cognitive Dysfunction in Depression, February 24, 2015.

MCCB, which emerged from the MATRICS initiative, included 7 domains and 10 tests (see Box 6-1). Following development of the battery, the team addressed challenges related to copyright, intellectual property, publication and distribution of the battery, and eventually starting a nonprofit company to publish the battery. This enabled the test publishing companies that own the rights to individual tests to distribute the battery.

An unexpected roadblock that emerged was FDA’s insistence on a co-primary measure that was functionally meaningful (Buchanan et al., 2005). Green thought that FDA might be inclined to take a similar stance with regard to cognition in depression. The need for a co-primary measure in schizophrenia trials led to the launch of another initiative, MATRICS-CT.

Workshop participants discussed whether the field should apply the MATRICS approach to building an assessment tool to measure cognitive impairment in depression. Several participants made arguments against taking such an approach. Barbara Sahakian, for example, said that it is important to utilize neuropsychological tests that are not only sensitive to

BOX 6-1

MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB)

- Speed of processing—category fluency, Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia (BACS) symbol coding, trail making A

- Attention/vigilance—continuous performance test (identical pairs version)

- Working memory—Maryland letter number span, Wechsler Memory Scale (WMS) spatial span

- Verbal learning—Hopkins verbal learning test

- Visual learning—brief visuospatial memory test

- Reasoning and problem solving—Neuropsychological Assessment Battery (NAB) Mazes

- Social cognition—Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test) (MSCEIT) Managing Emotions

SOURCE: Green presentation, February 24, 2015.

cognitive dysfunction in depression, but also demonstrably sensitive to change. This sensitivity to change will be important for assessing the efficacy of treatments for cognitive dysfunction in depression. She emphasized it was essential to not stifle progress in the field. Richard Keefe suggested that for depression clinical trials, the focus should be more on cognitive neuroscience processes or practicality for use in trials, yet he noted that none of the elegant and exquisite neuropsychological tests derived from the CNTRICS program have yet been used in a Phase II clinical trial. Green commented that the perspective of both academics and clinical trialists will be needed to settle the question of which tests are suitable for evaluating cognitive dysfunction in depression in multi-site clinical trials.

With regard to practicality, Catherine Harmer mentioned that if a battery were to be constructed, it would need to be deployable through general practitioners rather than psychiatrists in order to conduct clinical trials data in a more heterogeneous group of patients. Similarly to the MCCB, for international clinical studies it would also need to be translated into multiple languages, and norms would need to be established that account for variants in age, gender, culture, language, etc. According to Green, the MCCB is now available in more than 20 languages. He said that by starting with an international focus, some of the substantial translation challenges that MATRICS faced might have been avoided; however, he also

noted that multisite clinical trials pose additional challenges in terms of detecting a signal.