3

The Science-Information Climate

“There is no unframed information.”—Dominique Brossard

The scientific community has one of the many voices involved in public discussions about the societal applications and implications of GMOs. In addition to research on how a person thinks and makes decisions, social-science research focuses on the information climate that influences public opinions and societal discussions about science. Workshop presenters discussed both broad characteristics of the information climate and the publics, the groups of people that participate in societal conversations about science and technology.

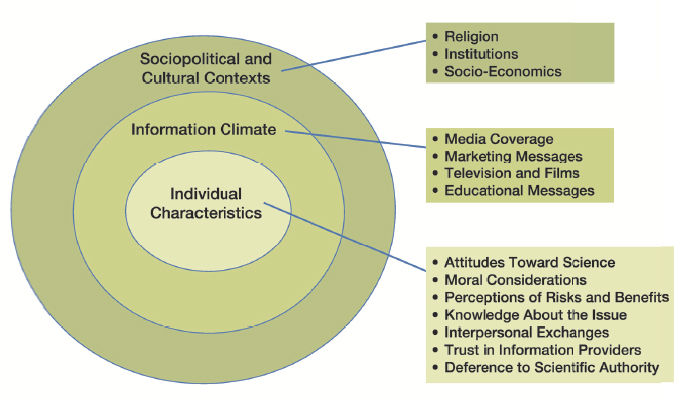

Dominique Brossard of the University of Wisconsin-Madison (UW Madison) described influences on public perceptions of science as having three layers: individual characteristics, the information climate, and sociopolitical and cultural contexts (Figure 3-1). Often, people focus only on individual characteristics, such as how the political ideology of one citizen may influence how that person perceives biotechnology, Brossard said. Indeed, research on how people think and make decisions has led to the finding that mental shortcuts (Chapter 2) influence a person’s perception of science more strongly than knowledge about the science. However, she underscored that the information climate—including messages from the mass media, commercial marketers, the entertainment industry, and schools—often shapes the mental shortcuts that people use.

“We think that we have some form of communication monopoly when it comes to new technologies—that if science speaks, the different publics will listen—and that is not the case,” said Dietram Scheufele of UW Madison. The assumption that the public is listening only to scientists about scientific issues is rooted in the deficit model, he stressed. The deficit model posits that people lack information and that when they gain more information from the scientific community, they will make better decisions that are based on their new knowledge. With that one-way science-to-public communication model being largely debunked by social-science research, others have worked to develop bidirectional conversations between scientists and members of the public. The underlying assumption of this approach is that the problem is with how scientists communicate and that ultimately this conversation will lead to a more effective way to tell people what will work better. However, according to Scheufele, many voices are competing to be heard: “Very often, we may not be perceived as the most credible voice unless we manage to position ourselves well in that overall [information] environment.”

Scientists lack a monopoly on communicating about new technologies, such as GMOs, in part because various groups can be effective in quickly and simply framing their viewpoints. Frames like visual imagery, headlines, or labels (such as “Frankenfoods”) can be quickly and easily understood because they play to perceptions that already exist in people’s minds. The concept of framing, originally described by Nobel laureates Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, is that all information is reference-dependent and is based on the beliefs that people hold, Scheufele said. People view complex science issues, such as GMOs, in many ways, said Scheufele. He emphasized that framing is an important tool that helps people to make sense of ambiguous information. “Frames help

Figure 3-1 Tiers of influence on public perceptions of science. SOURCE: Brossard workshop presentation slides 6, 9, and 10.

us to determine why an issue matters and to process highly complex information,” he stated.

“There is no unframed information,” Brossard stressed. In addition, the most powerful frames tend to be negative, she said. Still, a given frame can mean different things to different people because of how each person filters communication. How people react to a frame depends on who they are and on their perceptions of the person who shared information with them.

Frames can have unintended consequences, Scheufele explained, as in the case of the 1999 Washington Post headline, “Biotech versus the Bambi of Insects: Gene-Altered Corn May Kill Monarchs.”17 Framing the issue that way activated the existing image that most people have of the baby deer Bambi and quickly portrayed biotechnology in a negative way. Such frames are difficult to eliminate, and people may question the motivation of those who try to reframe them, Scheufele said. Because it is so challenging to “unframe” an issue, ideally scientists should think early on about how they will present their science in such ways that laypeople can attach the new information to what they already know, he concluded.

In the context of genetic engineering, many stakeholders contribute to the information climate through a variety of frames, including the mass media, policy-makers, scientists, research institutions, extension staff, farmer groups, industry, activity groups, and consumer groups, Brossard noted. Interpretations are affected by people’s culture, political dispositions, interest in science, world views, the source of the message, and a host of other factors.

The words that people use and associate with new technologies both create and shed light on the way in which new technologies are framed. William Hallman of Rutgers University discussed the particular associations that people mention when they think of GMOs and the effects of using particular words to describe them. Some of his research has involved asking people the first things that came to mind when he used various terms, including GMO, biotechnology, and genetic engineering. He found that the term used for the technology was important in determining the types of responses that people gave to the question. He examined whether people named objects or products or whether they provided responses linked to

________________________

17Weiss, R. 1999. “Gene-Altered Corn May Kill Monarchs,” Washington Post, 20 May 1999, Page A3.

emotions. The term agricultural biotechnology preferred by the Food and Drug Administration evokes the most neutral responses associated with stereotypical images of scientists. However, genetic engineering and genetic modification lead to many more negative responses, such as “mutant”, “monster”, and “nasty”.

MEDIA EFFECTS ON THE INFORMATION CLIMATE

The information climate is influenced through several media effects. First, scientific information can be framed in different packages, Brossard explained.

A second mass-media effect is what communication researchers call a spiral of silence. It occurs when a vocal minority receives increasing attention in the mass media. That attention is amplified as people talk about what the press is reporting. She said that ultimately people begin to believe that the minority opinion represents a majority opinion— in effect, it silences anyone who does not share the minority opinion.

Cultivation is another mass-media effect that has an impact on perceptions of science, Brossard said. “The more we watch entertainment media, the more we are embedded in a specific portrayal of reality that people end up thinking is the true one,” she stated. For example, the extensive amount of violence on television leads people to believe that the world is a meaner place than it actually is, she explained. Scheufele also discussed the powerful effects of cultivation as related to science, stating that most people do not interact with scientists or spend time in laboratories. Therefore, often their only images of scientists come from how they are portrayed in the mass media. People’s ideas of nanotechnology come from such movies as Terminator 3, and their images of scientists come from such television shows as The Big Bang Theory or such movies as Back to the Future. Scheufele has found that those effects persist even among science majors at his university—a demonstration of how powerfully the cultivated images shape perceptions.

Each mass-media effect exists within a broader information climate, Broussard stated. The broader climate is shaped by a wide array of stakeholders, including the mass media. In the context of GMOs, policy-makers, press offices in academic institutions, agricultural associations, industry, and consumer groups are among the actors shaping the information climate. Individuals in each also shape the debate as they converse with friends, family members, and colleagues. Mass-media effects within and among those groups are also important to consider when developing approaches to public engagement, according to Brossard.

Stephen Palacios of Added Value Cheskin discussed the role of consumer opinion about GMOs in forming industry marketing strategies and business decisions. From a marketing perspective, the debate around GMOs has already been framed negatively, Palacios asserted. Evidence of that can be seen simply by conducting an Internet search on the term GMO, he said. In a quick Web search, Palacios found that Google results yielded more Web sites against GMOs than in favor of them. Similarly, Palacios found that available movies and books on the topic of GMOs are largely from an anti-GMO perspective. That suggests that the average person who looks for information about GMOs will be presented with negative associations, Palacios said.

Anti-GMO groups have communicated thoughtfully and effectively, Palacios stated. Web sites are often sophisticated and multimodal with both short-form and long-form narrative portions and video. They may have components that appeal to various learning styles and include the ability to engage in “click advocacy” by facilitating direct donations to a specific anti-GMO cause. Some Web sites facilitate registering votes against particular companies through another form of click advocacy, he explained. Other sites, such as Netflix, include the title GMO OMG, an award-winning foreign film. Palacios opined that the title and style of the film target the millennial generation, and these forms of communication suggest a level of sophistication and an understanding of the messages’ targets.

Palacios indicated that although anti-GMO Web sites appear to have had little effect on the current application of genetic-modification technology in food, some evidence suggests that some food industries are changing their behavior. For example, Chipotle, which had the most successful quick-service restaurant initial public offering in the last 20

years, recently became the first restaurant to label GMOs and develop a plan to go non-GMO in the future, he explained. The Chipotle brand focuses on food integrity, so it has the potential to signal a trend in consumer interests that could influence others, he emphasized.

Food manufacturers and food-industry executives are influenced by consumer opinion regardless of whether the science demonstrates that genetically modified foods are safe, Palacios stated. To illustrate that point, he presented redacted data from a nationally representative consumer study that were shared with the chief marketing officer of a large food and beverage company. The survey focused on determining what consumers want with regard to natural and organic food and beverages and included a set of questions specifically about GMOs. Palacios stated that the summary headlines of the results of the consumer study include such statements as these:

- “Four out of ten consumers today are avoiding or reducing GMOs in their daily diet.”

- “GMOs have become potent symbols of the ills of the American food industry.”

- “Regardless of organic usage, all consumers express concern about the impact of GMOs on their health.”

Palacios noted that the concern over losing relevance and consumers is leading some food industries to have serious discussions about GMOs—whether to consider alternative sources of ingredients, labels, and public-relations activities that might need to occur if consumers become increasingly anti-GMO.

Palacios emphasized that at times both consumers and industry leaders have to make decisions before the science is conclusive. To major industries, consumer perception and opinion are the most important factors, and the fear of losing trust or relevance can drive what and how products are taken to market, a point also expressed by Hallman. Palacios suggested that the science community should focus conversations on targeted applications of GMOs more than working to change wholesale opinions.

Daniel Kahan of Yale University expressed skepticism about whether the results of the industry market survey discussed by Palacios are predictive of consumer behavior. Palacios responded that performance of market-research firms indicates that they are providing value to the industries that they serve. He reiterated that the reality of businesses is that they need to be prepared for changing consumer sentiment, although he did note that information from such surveys is merely taken into consideration in broader strategic discussions. Kahan cautioned that some people want to anticipate public reaction and start a debate where it is not currently happening and that this can have adverse effects on science communication.

ENGAGING PUBLICS IN THE INFORMATION CLIMATE ON GENETICALLY MODIFIED ORGANISMS

As several presenters noted, information that people consume is framed, but the meaning of the frames can be interpreted differently by different groups of people. Delborne of North Carolina State University addressed the notion of who the “the public” is and what this means for the science information climate.

The public is something of a misnomer. Delborne suggested that the plural term publics is more appropriate because it “acknowledges that out there in the world there are many different groups of stakeholders, interest groups, people with different accesses to information, different opinions, and so on.” However, he argued that audiences might be an even more fitting term.

“Audiences are created. The group of publics isn’t just out there waiting to be discovered. We construct publics or construct audiences when we attempt to engage them”—a concept that Delborne described in his 2011 publication Constructing Audiences in Scientific Controversy.18

Delborne discussed the results of a small scale unpublished study that he and his colleagues conducted on public perceptions of genetically engineered mosquitoes. The research team conducted door-to-door interviews with residents of Key West, Florida, in January 2013. First, interviewers explained the genetically engineered mosquito technology. Next, they asked the residents open-ended questions about the perceived hazards and benefits of introducing a genetically engineered

________________________

18Delborne, J. A. 2011. Constructing Audiences in Scientific Controversy. Social Epistemology 25(1):67-95.

mosquito to reduce the population of the mosquito species that are capable of transmitting dengue fever. Results of the study showed 60% of respondents in favor of introducing the genetically engineered mosquito, 23% opposed, and 17% neutral. Those results have different meanings to different people, Delborne explained. For example, Oxitec, the developer of the technology, might react positively to the findings but wonder how it will reach the 23% percent. Alternatively, anti-GMO advocates may be concerned about the findings and wonder, how do we define our message in a better way to make people more concerned? However, Delborne insisted what the results of the study demonstrate is the power and the superficiality of such measures of “support of” and “opposition to” a technology. “The public is constructed in this survey,” he said, in terms of who was home when the interviewers knocked on the door, what they were asked, what sort of information they were given, what they expected the results to do, and whether they thought that they were going to be affected by the mosquitoes. Delborne suggested that participatory forms of engagement are better mechanisms to learn about public perceptions of science and how the public navigates the information climate.

Delborne explained that there are three basic types of public engagement—public communication, public consultation, and public participation (Box 3-1).19 He emphasized public participation means that both members of the public and the scientists might be moved as a result of communicating. The openness of public participation requires both parties to accept some risk, he added.

The consensus conferences developed by the Danish Board of Technology (DBT) are an example of public participation, Delborne said. Experts and lay audiences interact at these conferences with the overt acknowledgment that facts and values are intertwined and inseparable. The purposes of the conferences are to promote learning through deliberation; to develop more thoughtful public opinions; and to generate new ideas and policy alternatives and affect governance decisions. “If you let people deliberate about an idea with good information and you ask them what they think about it, you get a kind of result that is different from what you get if you ask them briefly at their door what they think about GE mosquitoes,” Delborne asserted.

BOX 3-1

Three types of public engagement

- Public communication: one-way with information flowing from sponsor to publics in the form of education or outreach.

- Public consultation: one-way with information flowing from publics to sponsor through such mechanisms as opinion polls.

- Public participation: two-way flow of information between sponsor and publics.

SOURCE: Based on Delborne, workshop presentation, slide 11

Delborne shared several lessons learned about useful ways to conduct public engagement through his experiences at two consensus conferences, the 2008 National Citizens’ Technology Forum and the World Wide View on Global Warming organized by DBT. First, he found that it is possible to engage in high-quality deliberations with members of various publics. Second, framing the task and questions is important. During the World Wide View on Global Warming, the task was not framed as a debate about whether climate change was real but was bounded in terms of policy options that could be considered at the 2015 Copenhagen Climate Conference. Third, the logistics of constructing publics has an effect on who is in the room. For example, the amount of time that people were asked to use to take part in the National Citizens’ Technology Forum meant that the organizers had to offer a substantial stipend. That had the effect of attracting people for whom the stipend was substantial. The composition of the group helps to determine how seriously its deliberations may be taken. Fourth, Delborne noted that “some people are very willing to discount these types of engagement mechanisms because we don’t have a perfectly representative sample in the room” even though they will accept the results of an election in which not everyone votes. Delborne’ fifth lesson was that empowering participants in public engagement requires skilled facilitators. Facilitators must figure out the degree to which to empower

________________________

19Rowe, G., and L. J. Frewer. 2005. A Typology of Public Engagement Mechanisms. Science, Technology and Human Values 30(2):255.

participants to shift the agenda, decide what to discuss, and decide which experts they want to interact with, Delborne explained. “You risk not only being pulled in your position but being pulled off your agenda and pulled off what you want to talk about.” Sixth, for the ideas, decisions, or questions raised in public participation to be useful, “we have to find ways to connect them to real decision-making processes,” Delborne said. That brings to the forefront the tension between democracy and expertise, “two values that we hold very high in American society”. For many, “turning over some decision-making power to a public that might not align with experts’ views is scary and difficult,” he concluded.