2

Workshop Participant Observations

Over a series of three workshop sessions, the participants received briefings from 13 Service programs.1 Claude Bolton, Jr., executive-in-residence at the Defense Acquisition University, summarized these programs into two categories of technical baseline ownership: (1) the “clean sheet” situation with a new acquisition program, in which the government clearly owns the technical baseline, and (2) the situation where the program is in some process of “regaining” the baseline of an existing capability. The abstracts for these briefings are presented in Boxes 2-1 through 2-5.

The Advanced Pilot Training Family of Systems (next-generation trainer) program known as T-X was briefed at the workshop by Col. Peter Eide. He noted that this program was an example of doing things right. Bolton expressed his opinion that the implementation of the development planning approach, similar to the way things were done back in the Vanguard days, along with the pre-milestone B activities that included technical baseline ownership and activities, are well under way, ensuring that the “right people” appear to be in place along with the right resources (processes, tools, procedures, and techniques)—all supporting his assertion that the T-X program “gets it.” The only possible problem, he added, may be an ability to get or keep enough of the right people and funding in the future. Jon Ogg pointed out that the T-X session highlighted that owning the technical baseline (OTB) success is not because of policy, metrics, instructions, or processes. It takes smart people (knowledgeable and competent) making informed decisions to define the acquisition strategy of the program. He noted that they are using the proper tools to evaluate the alternatives while staying engaged with their customer, Air Education and Training Command, to keep them informed of the consequences, that is, development and production cost and schedule impacts as they evolve the T-X requirements.

Claude Bolton made the point that the Family of Advanced Beyond-Line-of-Sight Terminals (FAB-T) program presentation was in contrast to the T-X briefing, in that there was lack of leadership or ownership from its inception, from 2001-2009, which led the program to experience cost overruns of up to $1.2 billion and an 8- to 9-year delay. However, Bolton noted, under the leadership of the chief engineer for the past 3 years, the FAB-T program has been put on track. It appears now that the engineers do “real” engineering work by running analyses and models to verify contractors’ deliverables. Richard Roca concluded by adding that it was important to note

_______________

1 See Appendix B for a complete listing of presentations.

BOX 2-1

KC-46

Brig Gen Duke Richardson, Program Executive Officer

Tanker Directorate, Air Force Life Cycle Management Center (AFLCMC/WK)

The KC-46 tanker modernization program, valued at $52 billion, is one of the Air Force’s top acquisition priorities. KC-46 aircraft are expected to replace a portion of the Tanker fleet. In order to affordably sustain the KC-46 over its programmed 40-year life span, the Air Force acquisition community ensured adequate information is available to execute the weapon system’s acquisition and sustainment strategies. By militarizing a commercial freighter, the Air Force sought to reduce cost and technical risk by leveraging both commercial and military best practices. The Air Force utilized a contracting strategy that protected government interests through requirements development, acquisition of data and data rights, shared risk, and clearly defined technical baselines. Implementing these plans early in the life cycle is providing a technical baseline that balances both near-term fiscal responsibility and long-term sustainment needs.

BOX 2-2

Long-Range Stand Off

Mr. Ken Lockwood, Director of Engineering, Strategic Systems Division (AFLCMC/EBB)

The Long-Range Stand Off (LRSO) cruise missile program, valued at $8.7 billion, is a top Air Force acquisition priority. LRSO is the follow-on to the Air-Launched Cruise Missile (AGM-86B), focused on nuclear deterrent capability. In order to have a sustainable and robust system, the Air Force acquisition community will emphasize a robust design, mature manufacturing processes, and competitively priced production lots. The Air Force will realize a robust design via prescriptive design for reliability and design for manufacturing programs, with emphases on eliminating failure modes as well as increased government participation in the day-to-day activities of primes and suppliers. Beyond a robust design, the contracting effort will focus on clearly defined technical baselines and priced production lots to balance both near-term needs as well as the long-term sustainment of the LRSO cruise missile.

that every successful program presented at the workshop had a program office that had a deep technical insight into the operational environment in which the system would be used.

During the workshop, however, the participants also heard examples of programs that did not have control of their technical baseline. One of the best examples of why owning the technical baseline is important was provided by Col. Robert Strasser, system program manager, B-2 Division. He noted that neither the Air Force nor the prime contractor can reconstruct the inlet on the B-2 due to loss of the technical baseline. Strasser stated that only 18 percent of the organic system program office (SPO) personnel are science and engineering (S&E) professionals, and the prime is actually in the SPO as a systems engineering and technical assistance contractor, which he believes presents organizational conflict of interest and provides no ability for the government to independently challenge the prime’s technical risk assessments or cost estimates. And while the program has acknowledged that it understands that the lack of technical expertise within the program office is a fundamental flaw and has started to look for opportunities to hire a lead systems integrator contractor, Strasser stated that personnel policies have blocked any progress on this front.

BOX 2-3

Advanced Pilot Training Family of Systems

Col Peter Eide, Program Manager

The Advanced Pilot Training (APT) Family of Systems (FoS) acquisition program, commonly known as T-X, is one of the Air Force’s top acquisition priorities. By 2031, greater than 60 percent of the Combat Air Force fleet will be “5th generation.” APT aircraft and associated ground-based training systems, mission planning systems, and courseware will replace the aging 3rd-generation T-38 Talon fleet, thereby providing an essentially higher-quality training experience for our Airman. By leveraging mature designs—11 partner nations currently fly more advanced trainers—the Air Force plans to minimize developmental costs and reduce acquisition risk. Following in the footsteps of pathfinder programs like KC-46, the Air Force plans to maximize insight into and access to design-level data across the program life cycle. Tenets of owning the technical baseline (OTB) will help the Air Force be a more informed customer with the maximum opportunity to compete future modification and sustainment workload. Adopting OTB while also pursuing strategic agility at the outset of the APT program will help to ensure maximum capability at minimum cost.

BOX 2-4

Family of Advanced Beyond-Line-of-Sight Terminals

Dr. Thomas Kobylarz, Chief Engineer

The Family of Advanced Beyond-Line-of-Sight Terminals (FAB-T) presentation described a government chief engineer’s interpretation of a system’s technical baseline followed by evidence of how it is used to effectively execute a development and production program. The briefing starts with a definition of terms to place the work in context, then a brief background on the FAB-T, a satellite terminal program, which will be used to demonstrate the concepts. Examples specific to the program are given to quantify the system attributes that define the baseline as well as demonstrate the processes used to maintain control of that baseline and support informed programmatic decisions.

The Expeditionary Combat Support System program, Jeff Stanley noted, was designed to replace a multitude of disparate logistics information technology systems. Gary Kyle, however, claimed that the program clearly demonstrated lack of ownership of the technical baseline from inception. Kyle stated, “This program never had a good ‘as is’ baseline for the 200+ requirements it was supposed to replace.” Additionally, he stated, larger problems existed, such as lack of a clear understanding of the requirements; lack of proper tools, processes, techniques, and so on; and, most importantly, lack of the “right people,” defined as those who were educated or trained and had the appropriate mentored experience to do the job. Bolton pointed out that lack of the right people included people inside and outside the program management office. “They simply did not know what they didn’t know,” Ogg observed. Michael Griffin agreed, saying that “there was no technical baseline—no one owned it; it did not exist.”

Richard Roca expressed his amazement at the numerous examples of programs where the government funds the contractor for all the work yet does not retain rights to all the intellectual property generated by that funding: “If I understood the presentation, DCGS is an example where the Air Force does not have access to interface information yet is the sole funder of the work. This is incredible if true.” Furthermore, Roca noted, this issue is

BOX 2-5

Distributed Common Ground Systems

Mr. Steven Wert, Program Executive Officer

Presentation provided by Col Ray Wier, Chief, C2ISR Division

Battle Management Directorate, Air Force Life Cycle Management Center (AFLCMC/HB)

The Air Force Distributed Common Ground Systems (DCGS) weapon system is a top priority for Air Force acquisition. Air Force DCGS provides a global intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) capability that processes and exploits U.S. and coalition data. In order to ensure a secure and sustainable system, the Air Force will emphasize rigorous engineering processes, a government-owned integration process, and competitive contracting. By standing up the ISR Systems Engineering Center (ISEC), the Air Force will leverage original equipment manufacturer best practices and initiatives while maintaining government control of integration and testing. This will ensure that all new software and hardware will be vetted through a stringent Air Force-owned testing process before reaching the enterprise. Along with the ISEC, the Air Force will focus on decreasing sole source contracts, driving competition by acquiring data rights, and clearly defining technical baselines. Implementing these plans will balance both near-term needs, as well as the long-term sustainment of the Air Force DCGS Weapon System.

exacerbated by the fact that several of the Air Force’s acquisition programs are based on a commercial platform (e.g., the tanker), which clearly raises challenges compared to military programs that do not rely on a commercial system. In this case, Roca believes that defining the ownership of data rights in the early steps of establishing the technical baseline is critical. Ken Lockwood, director of engineering, Strategic Systems Division, Air Force Life Cycle Management Center (AFLCMC)/EBB, added that it is important to recognize that the technical baseline data may exist at many levels. To own it, he added, it is necessary to get to lower-tier suppliers. But, as Bolton pointed out, that leads to an even more fundamental concern for the Air Force—namely, how do we even know the current state of OTB in the Air Force? Because even for the ACAT-1 programs, which are by definition highly vetted and coordinated programs, Bolton thinks that many of the program offices do not have the organic technical capability to provide an independent assessment of the contractor’s claims.

Terry Jaggers, former chief engineer of the Air Force and former deputy chief engineer of the Department of Defense (DoD), asserted that the Air Force owns the technical baseline of all programs before contract award, at which time it “conscientiously” keeps or gives up [some or all] ownership to the prime contractor for the life of the program. However, he said, it is his understanding that there is no process to thoughtfully decide the extent of ownership for programs before the prime contract is awarded. While not all programs may require the same level of ownership of the technical baseline, there is no process to capture the trade studies as artifacts by which the Air Force decides how much to own and how much to cede to the prime contractor (or decide the level of some or any joint ownership), nor any evidence of risk management in terms of a reengineering capability or contract language to retrieve ownership, should it be required at some point in the program’s future. He thinks it would be important to do this decision process early and conscientiously before contract award, because regaining ownership is a resource-intensive (and perhaps impossible) task. Furthermore, Jaggers added that ceding any ownership to the prime at contract award requires a resource commitment to manage the risks from this decision, should unforeseen exigencies require ownership again (parts obsolescence and integration of subsystems being two prime examples).

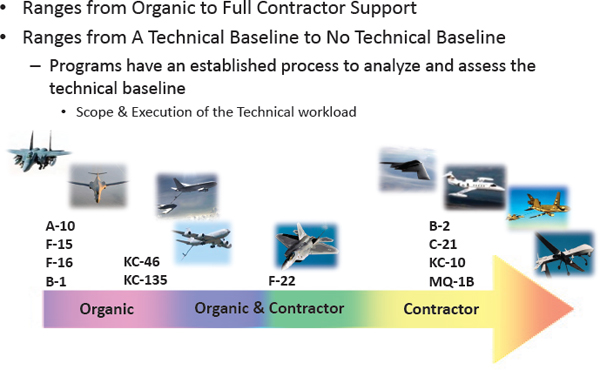

As seen in Figure 2-1, from Lt Gen John Thompson, commander of AFLCMC, current programs span the spectrum of ownership, which largely reflects decades of various acquisition reform initiatives where ownership was not a consideration but was rather “baked in” to the process. In other words, he pointed out, a program’s position on this spectrum of ownership is what it is as a result of the “acquisition reform” environment at that time, not what it should have been for the long-term life of the program after careful program-by-program delib-

FIGURE 2-1 Defining a program’s baseline. SOURCE: Lt Gen John Thompson, Commander, Air Force Life Cycle Management Center. Approved for release by SAF/PAO on December 18, 2014.

eration and decision. Jaggers thinks the Air Force should consider inserting a process of deliberations complete with trades and risk-reduction strategies during the pre-milestone A development planning process and perhaps capture these trades and decisions in the acquisition strategy plan for all future programs prior to contract award. In other words, he stated, ownership of the technical baseline should be a conscientious and deliberate decision process for every program.

Jaggers went on to say that ownership requires a standard and metrics to assess attainment and maintenance of ownership goals for an individual program. Based on the preliminary working definition provided by Col Strasser, he said that the A-10 could serve as one benchmark for a platinum level of ownership, not because the Air Force chose to own it at the beginning, but rather because Fairchild went out of business, and therefore the Air Force had to assume complete ownership at the end. Another participant asserted that there may be other benchmarks both within the Air Force and other services, but the limitations of a short workshop prohibited an in-depth discussion about the desired benchmark end-state vision and appropriate definition for full ownership of the baseline. Once a benchmark standard is created based on A-10 or other exemplar programs, Jaggers suggests that metrics be developed to ensure ownership is maintained and risk appropriately managed over the life cycle if ownership is ceded to the prime contractor. Furthermore, he believes that this should be a consistent status item at all major program reviews.

A recurring topic was the view, expressed by several workshop participants (Terry Jaggers, Trey Obering, Richard Roca), that the most important issue with respect to managing the technical baseline of a weapon system is for the PEO and PM to be able to oversee and manage the baseline with accountability, authority, and responsibility.

Throughout the workshop sessions, Claude Bolton repeatedly stated that “the Air Force was once the leader in the principles of program management.” Jon Ogg and Trey Obering, a former Director and Acquisition Executive for the Missile Defense Agency and currently a Booz Allen Hamilton executive vice president, highlighted that the loss of the technical baseline did not occur overnight; instead, they argued that the erosion of the fundamental ability to manage the technical baseline was the result of the leadership’s acquisition policies (e.g., total system performance responsibility, or TSPR) and organizational consolidations that occurred in the mid-1990s through early 2000. According to Obering, to regain ownership of the technical baseline, it will take unified leadership support to establish a policy that technical competence in the program offices is a strategic priority. Obering ended by stating, “absent strong leadership, the Air Force will not get out of its current state.”

As noted at the first workshop session by David Walker, initial steps are already under way, in that the Air Force has developed the Air Force Engineering Enterprise Strategic Plan 2014-2024.2 He stated that both the Secretary and the Chief of Staff of the Air Force define, as a high priority, the need to “address engineering enterprise workforce issues, including core competencies, structure, development and assignments.”3 Yet, according to other presentations, a recurring theme among all senior acquisition leaders is that they do not have the authority to rapidly hire and transfer critical engineering talent across programs and PEOs. A request for personnel action to move or hire a civil service engineer takes months to complete. Air Force Headquarters Deputy Chief of Staff for Personnel, HAF/A1, is in control of this, but A1 is not accountable for acquisition program success. Obering noted that reallocation of engineering resources to a higher priority is important to program success but currently has to be executed via the Unit Manpower Document (UMD), which, in his view, is very inflexible.

Lt Gen Thompson provided the workshop his perspectives during the second session (see Box 2-6). Following his presentation, Lt Gen Thompson stated that only the Secretary and Chief of Staff of the Air Force can change the current policy to direct that UMD management should reside at the AFLCMC level, which would provide the flexibility for his functional leads to control the movement, training, and promotions of their technical workforce. Obering noted that while the release of Air Force Engineering Enterprise Strategic Plan 2014-2024 represents a major and positive step forward, it remains to be seen how fully it will be implemented and what resources it receives.

Richard Roca agreed but stressed that to be effective, OTB must be a top-down cultural mindset originating at the highest levels of Air Force leadership and promulgated throughout the military ranks and the civilian staff. Sue Payton, president of SCI Aerospace, Inc., reminded the workshop that the presentations of RADM Dave Johnson, PEO Submarines, and VADM Terry Benedict, Director Strategic Systems Programs, were particularly powerful illustrations of the positive results that can be achieved when (1) there is a strategic long-term commitment from leadership to maintaining ownership of the technical baseline and (2) acquisition leaders are vested with the authority to retain, train, and plan personnel succession and are accountable and responsible for program success. This mindset, as expressed by Griffin, should include a core belief that the U.S. government, and particularly the Air Force, must fully embrace the need to control its destiny in regard to the acquisition, use, and support of its weapon systems and the organizational and logistical elements that support them. He continued that this mindset, if properly embraced, will necessitate changes in contracting, staffing, training, and promotion philosophies both within the military ranks and within AFLCMC support organizations, including the Air Force Research Laboratory, federally funded research and development centers (FFRDCs), university affiliated research centers, and professional service contractors.

Jon Ogg and Sue Payton believe the Air Force seems to be conflicted in its position on the value of a strong and effective engineering and technical workforce, for it is not clear that there is a unified position across Air Force program offices as to the need, role, or value of an organic engineering workforce. For example, as noted above by Lt Gen Thompson’s comments about the reorganization of Air Force Materiel Command (AFMC), the engineering functional home office (AFLCMC/EN), charged with training, organizing, and equipping AFLCMC’s engineering and technical workforce, does not retain the necessary control (UMD ownership) over its workforce

_______________

2 U.S. Air Force, Air Force Engineering Enterprise Strategic Plan 2014-2024, May 2014.

3 Ibid.

BOX 2-6

AFLCMC Initiatives and Perspectives

Lt Gen John F. Thompson, Commander, Air Force Life Cycle Management Center (AFLCMC)

For AFLCMC, our execution and functional portfolios span the spectrum from full organic support to full contractor support and everything in between. On the surface, the technical baseline is composed of data and information that provide the program office knowledge to establish trade-offs and verify, change, accept, and sustain functional capabilities, design characteristics, and quantified performance parameters at the chosen level of the system hierarchy, but “ownership” of it is much more. It ensures programs have established processes to analyze and assess weapon systems to enable informed decision making. Key points that influence the technical baseline in the Air Force are policy; types of funding; keeping appropriate knowledge, skills, and abilities; adequately resourcing programs and processes with manpower; and providing management and engineering tools on demand.

to allow him to make the moves or mandate and provide the training of AFLCMC engineers assigned to programs to ensure they are strong technical leaders that are seen by the PM and industry counterparts as “Heisman-level” players on their acquisition team.

However, Griffin observed that in spite of this absence of a clear Air Force mandate, there is a palpable sense of “ownership” by Air Force PEOs/PMs for their programs, which is clearly present in some, possibly even a majority, of workshop presentations. This sense of ownership is evidenced by some “should be” standard for all, Griffin asserted. Importantly, and very obviously, those PEOs/PMs who embraced such ownership were doing so not because of Air Force leadership policy, but in many cases almost despite the best efforts of Air Force and DoD seniors to militate against their efforts. Dedicated PEOs/PMs, Griffin noted, were clearly seeking “workarounds,” authorized or otherwise, to compensate for lowest price technically acceptable (LPTA) or small business set-aside procurement limitations, civil service hiring practices and limitations, or uniformed service staffing and promotion policies. He said that DoD, and particularly Air Force, policies and procedures should not be such as to impede PEOs/PMs from doing obviously correct things to enable mission success. However, during his presentation, Stan Soloway noted that there is a major disconnect between the messages from senior DoD leaders and the lower levels of management. One participant observed that it is no wonder the PEOs/PMs are confused, as it had been reported that Frank Kendall, the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics, had stated publicly that LPTA is not the way to contract for complex systems, while at the same time his subordinates were imposing LPTA as the solution for all things.

As Terry Jaggers previously noted, it appears that a “gold standard” for owning the technical baseline might be something like the A-10, and while the Air Force is forced to own it because the contractor is gone, it still serves as a much-needed standard or benchmark. Jaggers went on to say that whatever the gold standard, institutionalizing the ownership process and degrees of ownership is a leadership challenge. It will require a long-term cultural change before it is embraced by not only the acquisition cadre but the support functionals, and whatever standard is created should be institutionalized to outlast the current service acquisition executive (SAE). Jaggers voiced his greatest fear that the high standard set today by the current SAE will change in a few years and with each subsequent SAE. The Air Force, Jaggers believes, should try to set a technical baseline standard so that a foot of ownership equals 12 inches, not “the current king’s shoe size,” and this standard should be inculcated in all leadership functional training.

A recurring topic was the opinion, expressed by at least two participants (Michael Griffin, Trey Obering), that it is essential that senior Air Force leadership make it clear to all functional leaders supporting acquisition that the Air Force highly values technically trained and competent acquisition and engineering personnel.

Mike Griffin stated that a point that resonated during the course of the workshop was that “managing an engineering development program requires engineering talent because requirements cannot be written so carefully as to ensure program success and contractor performance.” However, as noted by Sue Payton, it is disheartening to find that professionally trained engineers comprise only 20-25 percent of Air Force engineering development programs. It is also of great concern, she noted, that the role of government engineers in the most important programs, such as the KC-46, is to witness, review, observe, and take passive action. In many cases, Air Force engineers are not really doing any engineering on the program; they are merely watching as others do. As described by Griffin, “They are art critics, not artists.” Payton then asked, “Who has the responsibility for growing the competence of the Air Force engineering workforce?” She stated that she has observed that the technical competence of the Air Force acquisition workforce has deteriorated dramatically because external organizations such as HAF/A1, SAF/AA, and SAF/FM have usurped the authority from SAF/AQ to manage acquisition personnel assignments, resources, and promotions. “Who are the custodians of the Air Force engineering workforce and culture?” questioned Payton. During the discussion of Aegis—the Navy’s weapon system that uses powerful computer and radar technology to track and guide weapons to destroy enemy targets—Kate Paige and Don Mitchell both described the Navy’s view on what OTB meant for its programs. RADM Paige elaborated that it means the government is accountable for the entire systems engineering process and its outcomes (see Box 2-7). Both Mitchell and Paige agreed that the Applied Physics Laboratory at John Hopkins University had played a key part in the government’s role as systems integrator, which, as one participant noted, was a very different management model from the Air Force uses. Another distinct difference between the Navy and Air Force, according to the two, was in the length of time an officer spends throughout his/her career working in a specific program. Paige commented that she had been associated with Aegis since 1976.

During this session of the workshop, Bolton stated that one cannot discuss OTB without positing that there is a cadre of experts on the government team who are capable of understanding the data and using it to make informed decisions. He continued by asserting that in the past the Air Force had, broadly speaking, access to the technical talent (uniformed and civil service staff, FFRDC, or professional service contractors) that is necessary for owning the technical baseline. However, as Griffin observed, in many of the presentations over the course of three sessions, the Air Force did not possess the capacity or tools to provide an independent assessment of prime contractor claims, judgments, or performance. In many cases offered at the workshop, the prime contractor was the primary or even the only source of relevant information. Obering believes that it will require the better part of a generation to remedy this situation, even with the full support of top Air Force leaders. One possibility might be to rely on the use of FFRDCs as a transition mechanism for the program offices as they regrow their organic capability. But as Ogg pointed out, the penetration of the FFRDCs is limited because they primarily support East and West Coast installations. For installations in lower-cost-of-living areas where DoD pay is comparable to local industry, he added that it is probably better to use the civil service hiring process to bring aboard strong technical journeymen and grow the workforce organically through formal education, hands-on experience, and rotational assignments in the Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL). However, this approach is also problematic due to the lethargic civil service hiring process, where it can take upwards of 6 months to hire an individual and little or no funding is available to allow the new employee to advance his/her academic education or participate in other forms of training, such as attendance at technical conferences, exchange with industry, or technical short courses. Additionally, Ogg noted that when a downturn inevitably hits, the recently hired junior staff are the first to be “surplussed” because DoD uses the last-in-first-out method that surpluses the most recently hired. This sends major repercussions through the universities that had encouraged their graduates to seek employment at the local Air Force installation. Jaggers observed that there may be a potential to leverage some aspects of the various workforce demonstration programs to alleviate several of the aforementioned issues, most notably the laboratory demonstration (Lab Demo) program or acquisition demonstration program authorities for things like expedited hiring. Jaggers added that the Air Force should also look at how the Navy in particular uses Lab Demo authorities to further the interests of the broader Navy programs, not just Navy science and technology workers. This review could be completed in the proposed terms of reference for follow-on study when reviewing other Services’ challenges.

BOX 2-7

Owning the Technical Baseline in the USAF

RADM (Ret) Kate Paige, USN, w/ Mr. Don Mitchell (JHU/APL)

RADM Paige and Mr. Mitchell discussed what “owning the technical baseline” means in the Navy’s Aegis program and MDA’s Aegis BMD program and how it is accomplished. They offered their historical insight as well as relaying the views of the current programs’ leadership. To support the discussion, they provided handouts that addressed a notion for organizing the major players in Defense acquisition, along with comments provided by the current program offices.

Ogg believes the Air Force leadership must realize that it is going to be an uphill battle to capture, retain, and train organic technical talent within the acquisition workforce. AFRL does a much better job of attracting, continuously training, and retaining technical personnel, some of who provide advice and counsel to acquisition program offices. Ogg went on to point out that as for engineering support contractors—often hired through advisory and assistance contracts (A&AS)—the contracting community has driven to LPTA suppliers. Once again, this makes it difficult to bring aboard top-notch technical talent because they find other opportunities working for industry rather than signing on with local contractors who pay minimum wage in order to secure Air Force Service contracts. Ogg also noted that support contractors cannot represent the Air Force in key leadership positions such as chief or lead engineer. So a conundrum exists: (1) FFRDCs that have limited geographic distribution, are expensive, and are capped by Congress; (2) the challenges of attracting, hiring, training, and retaining civil service talent; and (3) low-bid contractors who provide marginally acceptable technical talent. The result, Ogg concluded, is the current state of disillusionment and dissatisfaction with the acquisition technical workforce—“a perfect storm in the making!”

To fix the situation and have the capacity to own the technical baseline for Air Force programs, a key element should include changing the culture of how the Air Force values its engineering workforce, Ogg believes. As Kyle and Jaggers noted, the technical workforce includes military, civil service, and contractor S&E professionals. They stated that the Air Force needs a unified, holistic program-staffing policy that includes defining who is responsible for ensuring that for all Air Force programs the technical baseline is known and maintained for the life of the program. Unfortunately, Obering pointed out, the situation is especially dire for the uniformed members of the S&E workforce. As it stands now, there is no career path in the military clearly outlined for engineers that includes flag-level officers. He went on to point out that on the military side no career path exists beyond the rank of major for the engineering field—that is, there is not an “engineering duty officer” approach to three-star rank such as the U.S. Navy employs. Further complicating successful career upward mobility, Payton observed, is that members of the S&E workforce seeking to remain in the military must move out of the Officer Air Force Specialty Codes 61 and 62 to have promotion opportunities. Ogg suggested that perhaps the Air Force should create a bridge program that would allow for those in the military desiring to remain in engineering to move from military to civil service after putting in their minimum military tour. These individuals are high-value assets due to their military training, familiarity, and identity with the ultimate customer and their core values—integrity, service before self, and excellence—in all they do. Roca added that these individuals also bring experience in the relevant operational environment to the program office, which appeared to be a hallmark of the successful programs presented during the workshop.

Throughout the workshop, there were several examples of successful programs where the PM had extensive operational experience with the system. Col Janet Grondin discussed her program at Space Missile Command (SMC) and highlighted the importance of mentoring throughout her career (see Box 2-8 for additional details). Griffin and several of the other workshop participants agreed that SMC is doing a good job and that there clearly are good examples of programs that are running well at AFMC. Obering concluded by stating that SMC seems to prize science and engineering expertise and experience more than other Air Force product centers.

BOX 2-8

Launch Test Range System

Col Janet Grondin, Chief, Range and Network Division (SMC/RN),

Air Force Space and Missile Systems Center

Space and Missile Systems Center Range and Network Division (SMC/RN) is the program office responsible for the Modernization and Sustainment of the United States’ premier Launch and Test Range System (LTRS). LTRS consists of the Eastern Range (ER), operated by the 45th Space Wing (SW), and Western Range (WR), operated by the 30th SW. LTRS ranges support Title 10 U.S.C. 2273 for Assured Access to Space for National Security Payloads and are Major Range and Test Facility Bases (MRTFB) providing test range infrastructure for spacelift, ballistic missile, guided weapon, and aeronautical missions and systems. LTRS is responsible for the safe tracking and positive control of vehicles flying over thousands of square miles of broad ocean areas in the Pacific and Atlantic. Capture and government ownership/management of the full technical baseline began in 2009. LTRS benefits gained include the award of a fixed price range operations, maintenance and sustainment contract saving $700 million over the 10-year contract, award system modification contracts to best athlete, encouraging competition, improved Reliability, Maintainability, Availability and Dependability (RMAD) data collection and decisions for future system modifications.

Gary Kyle observed that while experience is essential for growing a college graduate into an engineer capable of making informed recommendations or decisions on the part of the program, within the Air Force no such mechanism seems to exist. Hands-on training or experience has become the exception for many entering the Air Force acquisition workforce. Ogg noted that the “Education with Industry” avenue for obtaining hands-on experience working real-world design and test challenges for those in the functional disciplines, especially engineers, has all but disappeared due to cuts to the training budgets. In addition, rotational assignments to AFRL to gain or refresh technological skills are problematic due to different personnel and pay systems and thus are an exception rather than the desired norm. Obering believes that the “Education with Industry” programs for engineers should be reestablished, possibly using cofunding with industry. Engineers need to have periodic hands-on experience at the AFMC sustainment center and/or test centers to keep their skills fresh and applicable. Payton wholeheartedly agreed and added that without engineering “know how” PEOs/PMs do not have the intellectual capital to be responsible for the program technical baseline. She said that for technical specialists supporting a PM to be useful, they have to be technically competent, and this requires training at the beginning of their career and continuous technical refresh through education and practice throughout their career. Payton noted that for practice to be relevant, it has to involve working at levels of detail far beyond that achieved when one is observing and commenting on the work of others.

Unfortunately, as Payton reminded the participants, even for the existing technical workforce, there does not appear to be a single organization or SAE that has the ultimate authority and responsibility to ensure that qualified technical resources are available to support the program offices. As a result, SAF/AQ is dependent on critical engineering talent for program success but does not have the authority to move engineers to fill critical program needs. This authority, stated Payton, is vested with the Air Force Personnel Center. The Air Force appears to have lost the flexibility to move engineers where they are needed due to the UMD paperwork approval requirement, observed Kyle. According to Ogg, if the Air Force leadership values technical competence and capability for acquisition success, they have it within their means to invest in the future workforce by providing enablers to acquiring, training, and retaining high-caliber technical talent. He believes that the program office engineering leads should articulate the program’s needs, and the functional home office leadership should work to supply the required capability through a combination of organic and contracted resources, with the program office supplying the funding for the contracted personnel. Ogg believes that the functional home offices must regain control of their technical

workforce to include resource allocations (assignments), training, and promotions. He said that the UMD should reside with the home offices in order for maximum flexibility in managing the workforce to avoid the onerous paperwork required for personnel reassignments across AFLCMC. Finally, Ogg commented, the functional home offices across AFMC, especially AFLCMC, should be held accountable for sourcing the program offices with the resources required to effectively execute their mission, independent of whether the source is organic or contracted.

Sue Payton agreed with Ogg’s suggestions and added that it is fundamental to acquisition program success and to intellectually owning the technical baseline to have the autonomy to manage the very engineering workforce needed for the job. She noted that while the acquisition chain is waiting 6 months or more for civil service personnel to be hired and reassigned, it is losing crucially needed engineering talent to other components within the DoD or industry who can direct hire, despite appeals of patriotism, stability, and education, among other factors, inherent to government work. The responsibility to grow the technical competency of the engineering workforce is diffused, underresourced, and inadequately supported with engineering tools. Jaggers observed that redressing this situation could take a decade, and because the most vulnerable budget items in program offices are systems engineering and training, it will take a renewed commitment from Air Force leadership to rectify this situation. Moreover, making this challenge even more formidable, Obering noted that as a result of past policies, “we’ve lost a generation of leaders capable of mentorship that could grow back the technical workforce within the acquisition community.” Ultimately, the issues highlighted in the discussions related to gaining back the technical baseline can be summarized by a comment made by Col Michael Meyer, deputy director for engineering, Office of the Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Air Force (Science, Technology, and Engineering): “There is a collision between the top-down mandate to own the technical baseline and the bottom-up loss of people and resources.”

A recurring topic was the view, articulated by three participants (Terry Jaggers, Jon Ogg, Sue Payton), that continuity, longevity, and mentoring in the engineering and technical fields, including a succession pipeline, are crucial for success of a program. They added that the Air Force needs to implement a formal, robust, and credible training and mentoring program to (1) transfer knowledge to upcoming acquisition professionals and (2) develop demonstrable business acumen in the acquisition workforce.

At various points during the three workshop sessions, Terry Jaggers argued that it may be cost prohibitive for some existing programs to regain ownership of the technical baseline at this point. Jaggers noted that while an aforementioned process should be created to conscientiously decide ownership strategy before contract award, the Air Force should consider a business case on existing programs before directing programs to expend resources to regain ownership. Foremost, he suggested the following should be considered: the type of program (Is it a core military aerospace power program requiring ownership like a fighter or bomber, or a commercial commodity program like a business system?) and the cost in terms of manpower and contract implications to regain it. Jaggers summarized his suggestion by asserting that at present, it seems all legacy programs want to regain ownership, and it is not completely clear that all programs require the expenditure of resources to do so. Regardless of how the Air Force decides to proceed with defining the process for determining how to own the technical baseline on existing programs, he felt that at a minimum, it should realign funding for development of the acquisition workforce. Payton then recommended using research, development, test, and evaluation (RDT&E) funding (otherwise known as Air Force budget account code “3600” funds) instead of operations and maintenance (O&M) dollars (otherwise known as Air Force budget account code “3400” funds) to fund functional training of engineers, which would eliminate the current situation where acquisition training competes against readiness challenges.4 Kyle concurred that there is a need to explore more use of 3600 (RDT&E) funds versus 3400 (O&M) funds, which has the additional benefit in that 3600 funds allow for more flexibility in hiring contractor technical support. However, Obering asserted

_______________

4 For definitions of 3400 and 3600 appropriations codes, see the Defense Acquisition University’s website ACQuipedia, “Research Development Test & Evaluation (RDT&E) Fund,” for 3600 codes and “Operations & Maintenance Funds,” for 3400 codes, https://dap.dau.mil/ acquipedia, accessed April 21, 2015.

that this suggestion would “undo” recent decisions by the Air Force financial community. He added that when Air Force leadership moved funding for AFMC engineering support function from 3600 funds to 3400 funds to allow for a “bill-paying” mechanism, it impacted the ability of AFMC to properly educate and stabilize the technical workforce. In spite of recent decisions that are counter to this suggestion, asserts Ogg, serious consideration needs to be given to converting the organic workforce over to 3600 funding, similar to the way the engineers and scientists in AFRL and test centers are funded. He said this is also true of the Navy’s engineering workforce. This would allow more flexibility in the hiring and training of the organic engineering workforce. He argued that the limitations of O&M funds create barriers to the hiring and training of organic resources, whereas the use of 3600 funding would allow the necessary engineering resources (most immediately civil service engineers) to be secured, trained, and employed in the support of program office needs.

The presentations from SAF/AQR and AFMC/EN both described a series of initiatives developed to rebuild the competency and capability of the engineering and technical workforce, yet little funding has been identified by SAF/FM, SAF/AQR, or AFMC to support the work required to bring these to fruition. Bolton and Ogg agreed that if a strong and capable engineering workforce is important to the Air Force, mission funding should be provided to help rebuild the workforce, which has atrophied over the past 10-15 years. This includes hiring top-rung engineers from academia or industry, funding advanced education and training, and having mentors and coaches guide careers through increasingly more important roles and responsibilities and ensuring that engineers gain the necessary core competencies to fulfill the needs of PEOs and PMs charged with executing programs.

While eligibility for tuition “assistance” at local colleges and universities may be adequate, Payton argued, in many instances it is not sufficient to maintain and acquire the level of technical engineering skills urgently needed, as stated by the Secretary and Chief in their recently released Air Force Engineering Enterprise Strategic Plan 2014-2024, “to continue to lead the world in the development of those cutting-edge weapon systems vital to the security of our nation and its allies.”5 Payton believes Air Force senior leadership must step forward with adequate funding to support their stated goals and priorities. Additionally, asserted Payton, there are serious gaps in certain core competencies of the engineering workforce such as radar engineers. Without sufficient continuing education funds to allow the Air Force to fully fund, in residence, advanced engineering degrees from highly respected graduate schools in areas critical to future Air Force requirements, Payton asserted that talented engineers will either leave the Air Force or lose their engineering edge. In the absence of Air Force funding, Kyle suggested that perhaps SAF/AQR or AFMC/EN should explore executable approaches to using the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics funding to make focused improvements in educating and training the acquisition workforce. Or, in an example offered by Roca, the Navy has used two concepts successfully: engineering development offices and working capital funding as it relates to the engineering support laboratories used by the program offices. Specifically, Roca noted that the Navy has been able to maintain and grow competencies in various technical areas supporting acquisition ranging from ship mechanical systems, such as pumps, to advanced weapons systems, such as missile guidance systems, by maintaining engineering-based organizations, both within the government and in allied organizations such as university affiliated research centers. These skills are used across a number of programs. Roca went on to say that technical organizations such as the Naval Surface Warfare Center assign individuals to programs based on program need and charge these programs for the use of the staff and equipment through the use of “working capital funds.” Fluctuations in need are the responsibility of the warfare center to manage, and they have been able to do so effectively. PEOs are not charged with maintaining the number and competencies of the technical staff and expect the warfare centers (and/or UARCs) to do so. In Roca’s view, this system works as well as it does because the typical Navy PEOs are staffed with people who are technically competent themselves, know what support they should expect, and demand it.

A recurring topic was the view, expressed several participants (Claude Bolton, Jr., Jon Ogg, Sue Payton), that the limitations of O&M funding and the inability to use RDT&E funding for hiring, retaining, and training the technical acquisition workforce create barriers to success. As a consequence, they noted, this lack of adequate and

_______________

5 U.S. Air Force, Air Force Engineering Enterprise Strategic Plan 2014-2024, May 2014.

timely funding limits the ability of acquisition-center functional leads from shaping the workforce to meet the demands for knowledgeable and experienced technical talent.

Terry Jaggers argued that the Air Force and/or DoD should investigate tools and policy to better integrate technical risk assessment by engineering and contracting. From the workshop presentations, he noted that the engineering and contracting functionals work separately with different agendas not only at the beginning solicitation stage, but during the proposal evaluation stage as well. For instance, from the presentation on the LPTA contract evaluations, it appears there is a technical acceptance evaluation done first by the engineering team, then a lowest-price evaluation performed by the contracting or cost team. To fully integrate the technical and contracting team, Jaggers asserted that policy should promote a concurrent evaluation of technical merits simultaneously with cost, and tools should be developed to analyze this joint technical and cost evaluation with some sort of integrated stratification of “realism” rather than pass/fail for technical, followed by lowest-cost selection. The analogy of evaluating proposals for both technical quality and cost concurrently would be similar to the schedule risk assessment process used by the Office of the Secretary of Defense programs. In addition, Jaggers argued that the Air Force could consider a separate “white collar engineering” contract to help struggling programs regain ownership during organic recapitalization at the earliest opportunity. Currently, AFMC and AFLCMC combine all of their technical support under an “Assistance and Advisory Services” label that includes everything from administrative support to professional engineers. While LPTA may be appropriate for administrative support, he stated that it is clearly not going to allow the Air Force to obtain access to the high-end engineering talent it needs to regain OTB. Therefore, Jaggers believes that a separate contract vehicle should be considered for this talent.

There is a clear “disconnect,” noted Griffin, between those at the higher levels of acquisition and contracting and individual PEOs/PMs. The former seem to believe that Air Force top-level policies are broadly and fully understood, that such policies have sufficient discretion—“wiggle room”—to allow intelligent program management decisions to be made, and that waivers for specific concerns are routine and easily obtained. The latter group, who are on the receiving end of top-level policies, he argued, clearly believe to the contrary. Such policies, Griffin stated, are seen by PEOs/PMs to be narrowly defined, rigid, restrictive, and essentially non-waiverable. Another major concern voiced by Kyle is that the LPTA contracts do not have the correct skills and experience criteria that allow contractors to provide the needed high-quality and specific technical resources. It appeared that some of the existing LPTA contracts were written to accommodate a larger group of contract awardees, including small businesses, and save money through artificially suppressed labor rates versus ensuring the ability to quickly and efficiently hire proficient, competent technical contractor resources.

Trey Obering reflected on the current contracting situation in which AFMC and AFLCMC mandated use of a specific contract vehicle, ACCESS, for A&AS support. This vehicle is an LPTA Small Business Set Aside contract with the average labor rate less than $45/hour. As Obering observed while driving to the base during a workshop held in Dayton, Ohio, last year, there were signs for gutter cleaner personnel in the area offering their services for $63/hour! He said, this does not bode well for the Air Force to obtain access to the type of talent it needs to regain OTB. AFMC recently started acquiring technical support services using the newly awarded Engineering, Professional, and Administrative Support Services (EPASS)/OASIS contract. The contract, he said, is supposed to be a “best value” approach instead of an LPTA contract vehicle. However, to date, the task orders awarded under EPASS/OASIS have been the same “dive to the bottom” seen under the previous ACCESS contracts. Bolton concluded the discussion by adding his concerns about using this mechanism to assist with maintaining the technical baseline: “Is it even possible to get high-quality and talented engineers on an LPTA contract vehicle?”

Other contracting mechanisms used in the past, such as the TSPR, do not work, asserted Griffin, as demonstrated by the problems that the Joint Strike Program Office has been forced to rectify to get the program back on track. Kyle countered with the perspective that TSPR worked exactly as planned, with appropriate government engagement through an aggressive insight approach, on the Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle program. Regardless of what contracting mechanisms are imposed by the contracting officer, Kyle argued, the PM and engineering staff must raise issues regarding ineffective contract vehicles to the highest level necessary for valid action and

redefining of the requirements versus accepting an untenable or dysfunctional situation. Obering reminded the participants that several of the program offices had expressed frustration that the contracting officer is not subject to any accountability for program success or failure as a result of the suitability of the contract strategy—just the terms and conditions of the contract. Therefore, there is a disconnect in incentives between the PM who needs the technical support and the contracting officer who is not judged on obtaining the technical support needed for program success but rather on whether the contract award is protested or not. For example, Obering continued, LPTA was not intended to be mandatory, but it has evolved that way; SPOs and contracting officers should exercise their own judgment in determining whether an offered price is too low to accomplish the work—not just accept the contractor’s low bid as gospel.

Sue Payton echoed Obering’s observation that the fact that contracting officers are not held accountable for program success—yet have the authority to constrain the PM from hiring the best engineering talent to support the program—is an issue that the Air Force must address to own the technical baseline. The goal, to own the technical baseline, is clearly achievable in the next decade, but it could be inconsequential to program success if the mission is ultimately compromised due to a contracting strategy enforced by a contracting officer intent on cost control as the paramount metric. After presentations by senior contracting officers and PMs, Payton said it is apparent that the contracting officers do not view themselves as having significant responsibility for successful program execution, only for a successful contract award and protest avoidance. Contracting officer mandates that dictate that a specific contract vehicle be used (i.e., LPTA for acquiring S&E support) can and have precluded the PM from hiring highly skilled engineering talent. Payton concluded her comments by highlighting that for a program office to be effective, the contract strategy must accommodate risk assessments, management, and control.

Both Griffin and Roca noted that the relationship between contracting and program offices in the Navy is significantly different from what the participants heard from Air Force program offices. In the Navy programs presented at the workshop, contracting officers in a properly run program report to the PM. Griffin concurred, “It appears that in the current era that Air Force contracting officers wield inordinate power over a program above and beyond the power of the Air Force PMs.” Roca cautioned that contracting officers do have a functional responsibility to exercise contracting processes. They also have a responsibility to ensure legal compliance. He noted that the Air Force does not seem to have distinguished between these two responsibilities for a PM. He said that it is important for a contracting officer to be able to both follow the PM’s direction in the day-to-day execution of the program and to also throw a flag if the PM does something that violates procurement law. This is a similar responsibility that every functional support entity in a program serves, but the PM should lead the program in controlling cost, schedule, and performance using appropriate contract types and industry incentives and awards. Kyle suggested that if the contracting officer and PM accept the Federal Acquisition Regulation “acquisition team” approach, then the contracting officer also has an inherent responsibility to ensure program success.

A recurring topic was the view, articulated by two participants (Terry Jaggers, Gary Kyle), that it is essential that contracts reflect the proper level of government technical and business engagement to include oversight, insight, data rights, and intellectual property consistent with the program’s life cycle acquisition strategy. Furthermore, they added, this should start at the earliest phases of the program and include a maintenance or sustainment approach for owning the technical baseline over the life cycle of the program.

The discussion turned toward what immediate changes to existing internal Air Force policy and processes would help support the OTB objective. During the first workshop session, Jeff Stanley had discussed the Air Force Acquisition Incident Review Board process that had been modeled after the safety review boards. He stated that a central issue in the programs that had been reviewed so far was a lack of good engineering fundamentals. The lack of engineering competence could easily be identified early on, according to Ogg, if major reviews with Air Force and Office of the Secretary of Defense staff and leadership in the Pentagon, at a minimum, included the PM and the program office functional leads for the areas of focus in the review. During the review, Ogg continued, there should be an emphasis on discussing the technical baseline at a level sufficiently detailed to demonstrate the PM’s

technical competence. In addition, Ogg pointed out that in the programs deemed successful, the chief engineer accompanied the PM to all major presentations, and the chief engineer knew and could articulate the program technical issues. In addition, Kyle thought it would be good for the Air Force to go back to enforcing engineering standards while accepting commercial standards whenever they make sense based upon the acquisition strategy.

Related to tools that could be adopted to gain back the technical baseline, Payton reminded everyone that throughout the workshop discussions with senior acquisition leaders and functional engineering leads, it was reiterated that there is a lack of critically needed engineering tools and modeling software. There is a crucial need to upgrade from a few seat licenses to site licenses for the tools and software that do exist, so that engineers can have ready access to standard engineering tools and modeling software that can be used across programs. Several of the workshop participants were surprised to learn that some financial management officers do not allow engineering tools and software bought by one program to be used across programs. Here again is an example, they pointed out, of an organization (SAF/FM) not accountable for acquisition success with the authority to impact acquisition program success. A variety of standard engineering tools and software should be bought at the enterprise level and then, Payton recommended, pushed out to all the program offices.

Sue Payton expanded on this a bit more by suggesting that while the Air Worthiness engineering process is well defined, there is not a robust, standard collection of engineering processes that other programs follow. As a result, she said, programs adopt the processes, tools, and modeling software of the prime contractors that are supporting the program office. Payton stated that if the Air Force is intent on owning the technical baseline of programs, then the Air Force must independently adopt standard engineering process, engineering tools, and modeling software, used Air Force-wide, to independently assess a program’s technical performance.

Terry Jaggers elaborated on this theme by suggesting that perhaps the Air Force should explore a “PEO certification” process similar to that of the Navy’s Strategic Missiles or Submarines PEO. He noted that for those critically important military-unique programs near and dear to the Navy’s heart, like strategic missiles or submarines, where ownership of the technical baseline is clearly a priority, the PEO has a “personal” certification responsibility to guarantee ownership of the system before it is deployed. This certification is vested in the PEO only, focusing accountability, responsibility, and authority. Jaggers said that it is unclear from the presentations if the Air Force has any similar process on those programs that reflect core military competencies of the Air Force where enduring ownership is valued (such as fighters, bombers, munitions, etc.). As both VADM Terry Benedict and RADM Dave Johnson discussed in their presentations on the Ohio class replacement program (see Box 2-9), the Navy has four personnel accountable for nuclear programs and has vested this accountability into a personnel certification process. In contrast, Jaggers noted that the Air Force often has numerous people responsible for a program, so it can be difficult to codify responsibility for the program’s success or failure of maintaining ownership of the technical baseline. On programs that require OTB, Jaggers noted that a PEO certification process could be considered either prior to prime contract award (reflecting responsibility and accountability to manage to the prescribed technical baseline) or before deployment (reflecting responsibility and accountability that the program was developed to ensure the prescribed technical baseline was instilled).

At the conclusion of the third workshop session, several participants reiterated that in contrast to the authority that the Navy’s program managers exercise, the rules under which AFLCMC operates impede its ability to acquire, grow, retain, and make available the right staff for programs. These participants believe that for the AFLCMC resourcing system to work efficiently, the commander, who is responsible for organizing, training, and equipping the program offices resident within AFLCMC, needs the flexibility to expeditiously hire, move, and train the workforce.

Several participants noted that ownership of the technical baseline is an Air Force-wide effort involving several functional offices—the government team—not just the acquisition community or program office alone. They believe that the plan and end-state required should be resourced and managed properly by all functionals in the Air Force. Other workshop participants noted that it is not clear that there is unity of effort across the Air Force right now. Within program offices, some believed ownership of the technical baseline should be addressed holistically to include engineering, the PM, A&AS contractors, and FFRDC support to meet ownership goals. Outside

BOX 2-9

Ohio Replacement (OR) Program

RADM Dave Johnson

The Navy’s Ohio Replacement (OR) will replace the current fleet of Ohio-class ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) as they begin to retire in 2027. The Navy began technology development in January 2011 in order to avoid a gap in sea-based nuclear deterrence between the Ohio class’s retirement and the production of a replacement. The Navy is working with the United Kingdom to develop a common missile compartment for use on OR and the United Kingdom’s replacement SSBN. OR will initially carry the Trident II D5LE missile.

Current Status of OR

The OR program is pursuing design for affordability initiatives and investigating various contracting and acquisition scenarios to reduce average follow-on ship procurement costs from an estimated $5.6 billion to $4.9 billion (in fiscal year 2010 dollars). The program intends to maximize economic order of quantity benefits by leveraging the Virginia-class program and the elements common with the United Kingdom’s SSBN. Program officials stated the OR and Virginia-class programs are aligned to support various contracting scenarios, including procuring the lead OR concurrently in a multiyear procurement with the Block V Virginia-class contract. The Navy will develop a legislative proposal in 2017 to support this approach.

The Navy has set initial configurations for areas including the torpedo room, bow, and stern. In 2014, the program completed ship specifications, set ship length—a major milestone—and started detailed system descriptions and arrangements. The contractor plans to build a notional submarine section to validate the fidelity of its new design tool. The program plans to have 83 percent of design disclosures (including drawings, and material procurement and construction planning information) and 100 percent of arrangements and the 3D product model completed prior to the start of lead ship construction—scheduled for fiscal year 2021. The Navy Capability Definition Document (CDD) was approved August 2012. The program is aligned with the JCID manual to submit to the Joint Requirements Oversight Council (JROC) for approval to support Milestone B in August 2016.

the program office, it requires support from financial management, contracting, personnel, and potentially other communities requiring leadership at the Chief of Staff and Secretary of the Air Force levels to make this a priority on critical acquisition programs. Several participants noted that many presentations cited the need for barriers to be lifted in the financial management community (using 3600 funding to resource an increase in the number and improve the technical capabilities of the acquisition workforce), contracting community (providing access to higher technical talent subject-matter experts for high-quality engineering services support, for example), and personnel community (allowing movement of high-quality organic personnel across programs within a PEO’s UMD for example). It is clear to some that these barriers and limitations need to be identified and actions taken in multiple functional communities to enable programs to meet any objectives set for owning the technical baseline. However, other participants believe ownership of the technical baseline should be deliberate on the programs that require it, but not on those that do not. They added that a future or follow-on study involving members of this functional community to jointly look for barriers and solutions to lift them would help to ensure a unified and cohesive Air Force effort.