WORKSHOP SUMMARY

Childhood cancer is an area of oncology that has seen both remarkable progress as well as substantial continuing challenges. While survival rates for some pediatric cancers present a story of success, for many types of pediatric cancers, little progress has been made. The American Cancer Society’s 2014 Facts and Figures special section featured detailed childhood cancer statistics (affecting children ages 0–14) that laid out a helpful benchmark for quantifying the progress and the problems that remain (ACS, 2014). But setting aside the statistics, when speaking of cancer or any other serious illness affecting children, even one diagnosis or death is one too many. Many cancer treatments are known not only to cause significant acute side effects, but also to lead to numerous long-term health risks and reduced quality of life. Even in cases where the cancer is considered curable, the consequences of treatment present substantial long-term health and psychosocial concerns (i.e., late effects) for children, their families, their communities, and our health system.

To examine specific opportunities and suggestions for driving optimal care delivery supporting survival with high quality of life, the National Cancer Policy Forum of the Institute of Medicine (IOM) and the American

Cancer Society co-hosted a workshop1 on “Comprehensive Cancer Care for Children and Their Families,” which convened experts and members of the public on March 9 and 10, 2015, in Washington, DC. At this workshop, clinicians and researchers in pediatric oncology, palliative, and psychosocial care, along with representatives from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), National Cancer Institute (NCI), Children’s Oncology Group, pharmaceutical companies, and patient advocacy organizations, discussed and developed a menu of options for action to improve research, quality of care, and outcomes for pediatric cancer patients and their families. In addition, parents of children with cancer and pediatric cancer survivors shared their experiences with care and provided poignant personal perspectives on specific quality-of-life concerns and support needs for children and families across the life spectrum. Audience participation throughout the workshop also provided important insights, reactions, and ideas.

The presentations and discussions represented a unique dialogue among passionate family members, highly dedicated clinician investigators, and advocates who strive not only for every child with cancer to be cured, but also for the child and family to have every opportunity to maintain quality of life throughout the illness course and beyond. The first day of the workshop included presentations providing an overview of the pediatric cancer landscape, prioritizing quality of life in the research and development pipeline, and optimizing clinical care and care transitions. On the second half-day, the presentations and discussion addressed specific opportunities for patient and family engagement in research and outcomes reporting, as well as opportunities for collecting, documenting, and using these and other needed data. Topics discussed included

- Fostering research and drug/therapeutic and diagnostic development for pediatric cancers that prioritizes increased survival and high quality of life;

- Developing, embedding, and documenting patient- and family-reported outcome measures and findings to support delivery of

___________________

1 The workshop was organized by an independent planning committee whose role was limited to the identification of topics and speakers. The workshop summary has been prepared by the rapporteurs as a factual account of what occurred at the workshop. Statements, recommendations, and opinions expressed are those of individual presenters and participants and are not necessarily endorsed or verified by the IOM. They should not be construed as reflecting any group consensus.

- optimal care that helps minimize pain, symptoms, distress, and other suffering as part of disease-directed treatment and follow-up care;

- Improving and expanding early integration of pediatric palliative care and psychosocial care in all care settings to support emotional and physical functioning, care continuity, and goal-concordant care for the affected child and family members;

- Enhancing access to high-quality end-of-life care in all care settings, as well as bereavement care for families;

- Routinely screening to assess and address patient and family needs for palliative, psychosocial, and rehabilitation support as part of childhood cancer treatment and long-term survivorship follow-up care across multiple transition points and care settings;

- Facilitating clear communication and smooth transitions from acute cancer care to long-term follow-up care across the life spectrum;

- Minimizing, monitoring, and treating side effects and late effects across the care continuum;

- Enhancing and expanding quality-of-life–focused data captured in pediatric oncology registries and other databases to guide improved care integration for pediatric cancer patients; and

- Examining the impact of childhood cancer diagnosis and treatment on family food, energy, and housing security and emerging care models to address health disparities.

The workshop focused on potential actions to address quality-of-life and quality-of-care improvements for children with cancer and their families across all care settings and care transitions. Participants were encouraged to consider connections between what we do in research, how we bring that into the care of patients, and how we continue to engage parents and families as voices that remind us of the importance of moving forward on their behalf and on behalf of their children. The planning process for this workshop assembled experts in different disciplines who would not typically convene to discuss shared challenges, objectives, and steps forward. As such, the very process of preparing this workshop exemplified what clinicians and health systems are striving to achieve for children and families—high-quality cancer care delivery across the care continuum that promotes truly interdisciplinary, person-centered, and family-oriented care.

This workshop’s particular emphasis on children also complements three other recent IOM initiatives, including IOM’s workshop on Identifying and Addressing the Needs of Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer

(IOM, 2013b), as well as two consensus reports for seriously ill adults, Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a Course for a System in Crisis (IOM, 2013a) and Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life (IOM, 2014). The suggestions put forth at this workshop build on those bodies of work by detailing the specific needs of children and families, including early integration of palliative and psychosocial care along with disease-directed treatment, for any age and for any disease stage, to improve the quality of life—not just at the end of life, but throughout the illness course and well beyond for surviving children and surviving family members. Public policy advocacy promoting these quality-of-life priorities is also escalating with the support of an organized Patient Quality of Life Coalition2 and associated legislative campaign.

This report is a summary of the presentations and discussions at the workshop. A broad range of views and ideas were presented and a summary of suggestions from individual participants is provided in Box 1. The workshop Statement of Task and Agenda can be found in the Appendix. The speakers’ presentations (as PDF and audio files) have been archived.3

OVERVIEW OF THE CURRENT LANDSCAPE IN PEDIATRIC CANCER RESEARCH AND TREATMENT

The workshop began with several presentations that provided an overview of the current landscape in pediatric cancer research and treatment, with some emphasis on the unique challenges and opportunities in pediatric drug development, as well as challenges in addressing treatment toxicities and late effects.

Most of modern oncology is underpinned by early advances in treating pediatric cancer. In introducing the first workshop session, Phillip Pizzo, professor of pediatrics/infectious diseases at Stanford University, explained that pediatric oncology has really been the exemplar of many key elements in quality health care, including interdisciplinary team-based care, the connection of compassionate health care professionals, translational research that brings basic discovery from the laboratory to the clinic and back, continuity over the life journey, and combining compassion with care along the continuum. Gregory Reaman, associate director of the Office of

___________________

2 See www.patientqualityoflife.org (accessed May 29, 2015).

3 See https://www.iom.edu/Activities/Disease/NCPF/2015-MAR-09.aspx (accessed March 15, 2015).

BOX 1

Suggestions Made by Individual Workshop Participants

Improve and Accelerate Pediatric Cancer Drug Development

- Maximize use of regulatory authority provided through existing legislation to address indication-based waivers. (Greg Reaman)

- Create incentives that reduce industry risk much earlier in the process to encourage new pediatric drug development, particularly when no adult indication exists. (Christina Bucci-Rechtweg, Reaman)

- Conduct long-term longitudinal observation studies and combination therapy toxicity studies for newer targeted cancer agents in pediatric populations to evaluate the short- and long-term safety concerns. (Reaman)

- Mandate studies of relevant adult drugs in pediatric populations earlier in the testing process. (Reaman)

- Provide more funding mechanisms, such as small business innovation research grants and targeted use of disease foundation funding, to support drug development for pediatric cancers. (Beth Ann Baber)

- Support more patient-focused drug development that includes quality-of-life assessments. (Reaman)

- Enhance collaboration among all stakeholders (e.g., the Children’s Oncology Group members, academic centers, clinicians, patient advocacy groups, and pharmaceutical companies) to define trial outcome measures and facilitate pediatric drug development. (Bucci-Rechtweg, Reaman, Lillian Sung, Christina Theodore-Oklota)

- Support research on late effects to understand the pathogenesis and dose dependence of late effects, to develop risk prediction models, and to develop targeted interventions to reduce risks. (Smita Bhatia)

Improve Access to Early Pediatric Palliative and Psychosocial Care

- Develop and disseminate evidence-based standards in pediatric palliative care and psychosocial support, and facilitate and incentivize implementation. (Peter Brown, Paul Jacobsen, Mary Jo Kupst, Lori Wiener, Joanne Wolfe)

- Include core competencies in pediatric palliative care in the curricula of schools of medicine, nursing, social work, psychology, and counseling. (Chris Feudtner)

- Provide more information to parents about how pediatric palliative care can help them and their children throughout the care continuum. (Wiener)

- Integrate palliative and psychosocial care services, with a sound business plan and program support, into all pediatric oncology practices. (Feudtner, Wiener)

- Prioritize communication and care supporting family-oriented shared decision making and goal-concordant treatment, including establishing payment mechanisms for coordinated care planning. (Jennifer Mack)

- Train health care providers to initiate advanced care planning discussions. (Mack)

- Include screening for psychosocial needs of children and families in accreditation requirements. (Brown)

- Embed the team approach to palliative and psychosocial care with oncology treatment that integrates expertise of social workers, psychologists, psychiatrists, and child life specialists throughout the care continuum. (Wiener)

- Support more research on pediatric palliative care and psychosocial needs across the care continuum. (Feudtner, Anne Kazak, Kupst, Mack, Wolfe)

- Determine the optimal methods and timing for psychosocial screening and assessment, and support the development of targeted or personalized interventions. (Kazak, Kupst)

Improve and Expand the Use of Pediatric Patient-Reported Outcomes (PROs)

- Define and routinely collect a core group of PROs from patients and parents, and integrate them into the health care delivery system to improve clinical care. (Mary Brigid Bradley-Garelik, Pamela Hinds, Theodore-Oklota, Bryce Reeve, Sung)

- Include PROs as a default in pediatric cancer clinical trials, and ensure that the data are analyzed and published. (Reeve, Sung)

- Educate clinicians and administrators on the value of PROs. (Reeve)

- Educate children and parents about the importance of self-reporting and how their clinical care team will use the information. (Hinds)

- Develop a dynamic, integrated electronic system to routinely screen children for symptoms and other key patient outcomes to provide real-time feedback to clinicians. (Reeve)

- Develop PROs that are appropriate for patients in different age groups. (Sung)

Improve Long-Term Follow-Up Care and Outcomes

- Optimize long-term health of survivors by partnering with parents and patients to capture data on issues related to growth and development, impairment of vital organ function, fertility and reproduction, second cancers, and the impact of all of these sequelae on quality of life. (Bhatia)

- Provide a treatment summary and survivorship care plan to patients upon completion of treatment for pediatric cancers. (Lisa Schwartz)

- Educate clinicians, patients, and parents about the long-term complications of pediatric cancer treatment, follow-up care needs, and health promotion. (Bhatia, Schwartz)

- Continue to monitor and address the long-term health and well-being of childhood cancer survivors, particularly the chronic health conditions and life-threatening or fatal conditions that increase over time. (Bhatia, Kevin Oeffinger)

- Standardize long-term follow-up care and update guidelines regularly. (Schwartz, Bruce Waldholtz)

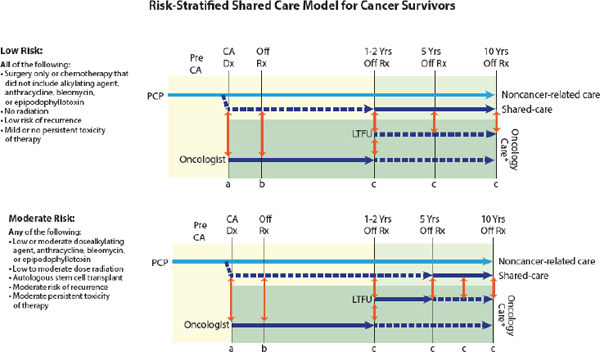

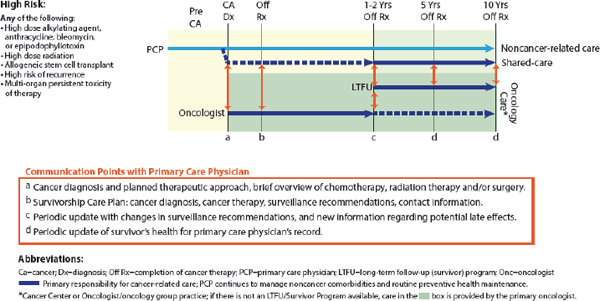

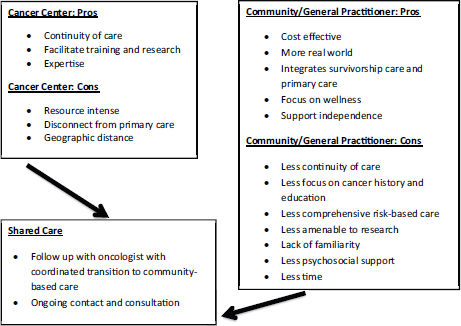

- Identify best practices and best models of care for transitions from active treatment to short- and long-term follow-up. (Kupst, Schwartz)

- Assess and address transition readiness. (Schwartz)

- Direct high-risk patients to specialty clinics for long-term follow-up care. (Oeffinger)

- Identify the demographics, disease characteristics, and treatment profiles that predict risk or resiliency post-treatment. (Patricia Ganz, Kazak, Schwartz)

- Support a national registry of cancer survivors to enable follow-up care and research on long-term complications of cancer treatments. (Peter Adamson, Richard Aplenc, Bhatia, Ganz)

- Standardize information collection to assess endpoints across different health care systems. (Reeves)

- Develop information and decision support tools (e.g., prompts and drop-down menus in electronic medical records) to inform primary care providers (physicians, nurse practitioners, nurses, social workers, etc.) about unique care needs based on a patient’s cancer history. (Kupst, Oeffinger, Phillip Pizzo, Waldholtz)

- Systematically collect standardized sociodemographic variables in pediatric cancer clinical trials, and direct patients in need to existing support programs. (Kira Bona)

Hematology and Oncology Drug Products in the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research at FDA, agreed, adding that childhood cancer care today involves a “unique integration of clinical practice, patient management, and clinical research [coupled with] a highly effective national clinical trials infrastructure”—all pivotal to the successes achieved.

Today, cancer is diagnosed in an estimated 10,380 children ages 0–14 each year (ACS, 2014), and the number of childhood cancer survivors in the United States was estimated to be 388,501 as of January 1, 2011, of whom 83.5 percent were at least 5 years post diagnosis (Phillips et al., 2015). However, despite notable advances in treatment and resulting improvements in survival for some types of childhood cancer, it remains the leading cause of disease death among children, with approximately 1,250 children losing their lives to cancer each year (ACS, 2014).

Childhood cancers typically are quite different from adult cancers, and the smaller number of pediatric cancer cases overall presents barriers in conducting the large-scale clinical research necessary to develop and deliver new treatment breakthroughs, particularly for the less commonly occurring cancers. As a result, some types or stages of pediatric cancers have not experienced any significant treatment advances or improved survival (Smith et al., 2014). “Any disease is rare until it knocks on your door,” said Jonathan Agin, director of external affairs for the Max Cure Foundation, development liaison and general counsel for the Children’s Cancer Therapy Development Institute, and the father of a daughter he lost to DIPG (diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma), still one of the most lethal childhood cancers. Jennifer Cullen, director of epidemiologic research at the Department of

Defense Center for Prostate Disease Research, and the mother of a daughter who was diagnosed with medulloblastoma and died after 13 months of grueling treatment and suffering many treatment-related complications, stressed that “the public health importance of childhood cancer is obviously not a function of the sheer volume of new cases that occur each year. It is a function of the high malignant potential of each of those cases, the devastating impact of treatment on the survivors, and the many years of life lost for each of those who don’t survive.”

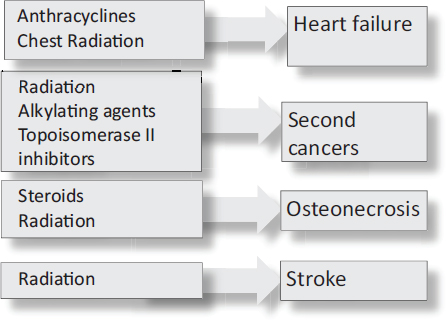

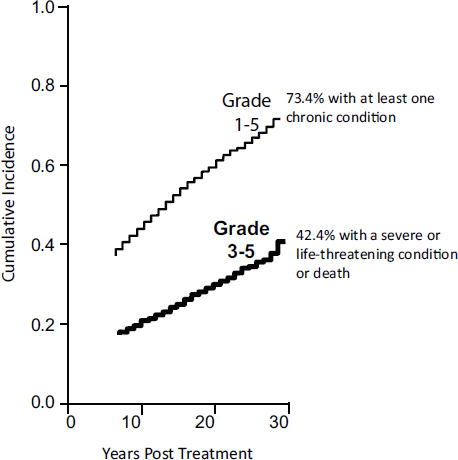

Smita Bhatia, director of the Institute for Cancer Outcomes and Survivorship at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) School of Medicine, described major landmarks in pediatric oncology, noting that once it became apparent that chemotherapy and radiation therapy could cure children of cancers, “We threw the kitchen sink at our children.” In the 1980s and 1990s, researchers began to document the long-term effects of cancer therapies and see the relationship between dose or type of therapy given and the adverse effects experienced. Recognizing that radiation therapy was responsible for many of those long-term sequelae, physicians began substituting effective drugs for radiation therapy, as well as tailoring therapy based on risk factors for developing late effects from cancer treatment.

But many pediatric patients still receive aggressive treatments with a high probability of significant long-term side effects, such as altered neurological development of the child. Concerns about these late effects can sometimes influence the choice of treatments. For example, Beth Anne Baber, chief executive officer, director, and co-founder of The Nicholas Conor Institute for Pediatric Cancer Research, said she and her husband decided against standard treatment (bone marrow transplant) for their son who had developed a brain cancer at the age of 15 months. She said bio-marker tests suggested that he did not have an aggressive tumor and such transplants have serious short- and long-term side effects. “We decided to downgrade the chemotherapy protocol because we wanted our child to have the highest quality of life. If it wasn’t for a long period of time, he would at least be able to be a child,” she said.

Bhatia also discussed efforts to improve treatment outcomes for children with cancer through a focus on improving adherence to treatment protocols. Bhatia noted that studies showing that children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia who do not adhere to the standard 6-MP4 treatment protocol have a higher risk of relapse (Bhatia et al., 2012). Consequently, a

___________________

4 6-mercaptopurine.

comprehensive approach is now under investigation to determine whether it can improve adherence to the medication schedule among pediatric leukemia patients, with the help of text messaging, directly supervised therapy, and education, she said.

Trends and Challenges in Developing Drugs for Pediatric Cancer

One potential way to improve cancer treatment outcomes and reduce treatment toxicities is through molecularly targeted therapies. Such targeted therapies are already available for treating some pediatric cancers, although most targeted therapies are only FDA approved for treating adults (Adamson, 2015). These therapies target genetic alterations that affect the growth pathways involved in cancer. Many genetic flaws have been identified for childhood cancers, which tend to have fewer gene mutations than adult cancers, Reaman reported. But most of these mutations are relatively rare and often do not occur in adult tumors. Most pediatric cancers have mutations in embryonic genes and lack mutations in genes relevant to the molecularly targeted agents already on the market or being developed for adult cancers, with the exception of a few targeting certain types of leukemias and brain tumors (Northcott et al., 2012). “We need to recognize that there is a biologic distinction in the malignancies diagnosed in children and adolescents compared to adults,” said Christina Bucci-Rechtweg, global head of maternal health and pediatric regulatory policy at Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation.

Immunotherapies that enhance the immune system’s ability to destroy cancer cells are also showing promise in treating some pediatric cancers, including brain tumors and leukemia (Grupp et al., 2014; Yu et al., 2010). Both immunotherapies and molecularly targeted therapies still have toxicities and pose short- and long-term safety concerns, Reaman noted (Dy and Adjei, 2013). Side effects linked to the use of these therapies could affect the normal development of children and put them at higher risk of developing certain disorders, he stressed, adding that there are insufficient long-term exposure data in adults and little combination toxicity data to guide treatment in children. These new types of drugs “will really be a new paradigm for pediatric cancer and long-term follow-up,” Reaman said.

He noted that it is challenging to do research and drug development for pediatric cancers because fewer than 15,000 pediatric cancers are diagnosed each year in the United States, which means that the number of children eligible for any particular clinical trial is small, especially because molecular

targeted therapies often only work in small subsets of cancers. Traditionally, the challenges associated with the small and scattered numbers of pediatric cancer patients available for clinical trials have been met with multicenter clinical trials in the United States. To test targeted agents, such trials might have to expand globally to enroll sufficient numbers of pediatric patients, said Malcolm Smith, associate branch chief for pediatric oncology at NCI. “It’s really important to nurture the infrastructures and collaborations that exist and to strengthen our ability to collaborate with partners in Europe, Asia, and other places,” he said.

Even if this challenge can be overcome, pharmaceutical companies are reluctant to develop drugs that will have such a small market, Reaman noted. He pointed out that the genetic changes responsible for some pediatric cancers, such as Ewing’s sarcoma, have been known for some time, but drug companies are not using this information to develop agents that target these genetic defects. Baber noted that drug companies have more incentives to develop drugs for rare chronic diseases in children in which the drug will be taken during the entire lifetime, as opposed to drugs for pediatric cancers, which are taken for a much shorter time period, and thus have a limited potential to achieve a return on the investment to test the drugs.

The higher bar set for cancer drugs for children versus adults also dampens the enthusiasm of companies to develop them, Reaman said. Drugs that target adult cancers can receive FDA approval based on evidence of short-term benefit to patients—the ability to extend life by a few months—whereas more long-term benefits with minimal side effects are usually demanded of drugs for pediatric cancers, according to Reaman. Smith agreed, noting that most regulatory approvals for adult indications are for people who are not expected to live for a long period after their treatment, whereas children could potentially live for many decades after treatment, “We want to know the impact of a new drug on the survivorship for the pediatric patient, including its likelihood of inducing cognitive or cardiac disorders and second cancers,” he explained.

Consequently, most cancer drugs are initially developed for adults, and if they are found to be ineffective for that population, they are abandoned without further testing to see if they might useful for treating pediatric cancers. “Unfortunately, that deprives us of the opportunity to test what might be a promising drug in the pediatric population,” Reaman said. Developing formulations that are appropriate for children can also be challenging, especially because many new cancer medications are given orally. “Giving a capsule that would choke a horse to a 2-year-old child is not possible,” Reaman said.

He suggested several possible avenues for encouraging more drug development for pediatric cancers, including current legal incentives. To repurpose targeted cancer drugs approved for adults so they can be used for pediatric cancers, Reaman suggested maximizing the regulatory authority provided by current legislation to address “indication-based waivers.” For example, the Pediatric Research Equity Act requires drug companies to study their products in children under certain circumstances. When pediatric studies are required, they must be conducted with the same drug and for the same use for which they were approved in adults (Yao, 2013). This may require redesigning early-phase studies to enable more appropriate dosing for children. To encourage more expedient development of pediatric cancer drugs, FDA could mandate that studies of relevant adult drugs be conducted on pediatric populations earlier in the testing process, Reaman noted.

A bigger challenge is fostering the development of new cancer drugs that are not already in use in adults and that would target pediatric cancers. According to Reaman, there is currently no “legislative fix” for this. He suggested providing incentives to industry that may reduce the risk of such early development, instead of just providing extended market exclusivity, patent extensions, and other financial incentives that are only offered once a drug has proven its worth. Bucci-Rechtweg agreed, stressing that current incentives benefit companies late in the life cycle of drugs rather than earlier in drug development. She added that one incentive would be a more expedient review process by FDA because reducing the time lines for reviewing a new drug provides financial benefits to the drug’s sponsor. In 2012, FDA created a program in which it could give priority review vouchers to sponsors of drugs for rare pediatric diseases (Varond and Walsh, 2014). But that benefit has been diluted by other priority review mechanisms at FDA, Reaman said.

Reaman suggested that another option is to develop public–private partnerships to fund the development of new drugs for childhood cancers. NCI is already engaged in such partnerships to support the development of targeted drugs for Ewing’s sarcoma and neuroblastoma. Collaborations among private foundations can also be useful (see Box 2). Lee Greenberger, chief scientific officer at the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society (LLS), noted that when LLS recognized that a study could be expanded to address several different types of leukemia, they provided $100,000 to fund it and asked the St. Baldrick’s Foundation, which funds the most promising research aimed at curing childhood cancers, to match that grant. “The concept of collaboration across foundations is very important,” he said. LLS also collaborates with the NCI-supported Children’s Oncology Group (COG) to

BOX 2

Leukemia & Lymphoma Society—Funding Research

Lee Greenberger of the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society (LLS) described the research funding activities of LLS and how they can serve as a model for fostering drug development for pediatric cancers. The Society’s mission is to cure leukemia, lymphoma, and myeloma and to improve the quality of life of patients with these blood cancers and their families. Since the Society was formed in 1954, it has invested more than a billion dollars in research grants. It currently has 320 active academic grants, including career development training awards, translational bench-to-bedside awards, “new idea” awards, and awards for specialized centers of research.

Greenberger noted that their career development awards for researchers early in their careers have been especially productive because those who receive them tend to continue to do research on blood cancers. Some ended up running major programs in this area 15 to 20 years later, including two researchers at the forefront of discovering or testing innovative immunotherapies that are showing promise in treating a number of cancers.

A more recent LLS initiative is the Society’s Therapy Acceleration Program (TAP) aimed at accelerating innovative therapies that are first in their class. TAP helps bridge the “valley of death” between basic and applied research by enabling promising agents in late preclinical development to enter and progress from this late discovery stage through Phase III clinical trials. “Drugs in the early state of development are at the biggest risk of failure. Couple that with a rare disease and you often see biotech companies and particularly big pharma run in the other direction,” Greenberger said. TAP was started “as a way to get these therapies and drive them into the clinic and find out if they will work,” he said. Once that initial evidence is available, drug companies are more likely to do the additional testing needed to bring a drug into the market. TAP includes “Biotechnology Accelerator Awards,” which are partnerships with biotech companies in which the Society splits the costs of pursuing an interesting idea with therapeutic potential, as well as “Academic Concierge Awards” in which the Society will work with outside companies who they fully fund to make a drug and do the necessary preclinical studies on it so that an academic investigator can test it in a clinical trial. TAP also has a clinical trials program that helps patients gain access to trials in their local communities.

In the 8 years it has been in operation, TAP has had 47 partnerships, 25 of which are still active, and a total of $80 million has been invested in the program. In combination with the Society’s other grant programs, TAP has fostered Food and Drug Administration approvals of three drugs for blood cancers and helped advance more than a dozen other promising agents into the clinical trial pipeline. “The Therapy Acceleration Program has been a good model to advance opportunities, particularly for rare cancers,” Greenberger said. “We are making good progress toward cures for blood cancers, with increases in survival not in terms of months, but in terms of years.”

SOURCE: Greenberger presentation, March 9, 2015.

fund clinical trials of drugs for leukemias or lymphomas, although he noted that such collaborations are sometimes difficult to manage due to different goals and time lines.

Pizzo noted that the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation collaborated with researchers who discovered drugs that target some of the genetic defects that cause cystic fibrosis and fostered the development of those drugs, which are currently on the market. “Could their approach work for developing drugs for rare pediatric cancers?” he asked, noting that even outside of pediatric oncology, pharmaceutical companies are sinking less money into funding research and development, so “partnerships with foundations and academia become ever more important.” He added that parents “can make a huge difference in helping to lead that effort.”

Reaman echoed the plea for parents and advocates to become more involved in drug development and noted that advocates did make a difference in adult drug development. “I think there is enormous opportunity for families of patients,” he said. However, he added that the one-foundation-one-disease approach may fracture the ability to make progress, noting that there are about 3,000 organizations involved in raising money related to cancer, all with their own agendas. Otis Brawley, chief medical officer of the American Cancer Society, also stressed the need to avoid “disease Olympics,” in which advocates press for research on one type of cancer at

the expense of research on another. “We are all arguing for a larger slice of the same size pie,” he said. He pointed out that many genetic discoveries on pediatric cancers have proven beneficial in adult cancers and vice versa. “All these cancers have things in common and we need to realize that if one cancer is bettered, all cancers are really bettered.”

Baber suggested more general public funds, such as small business innovation research grants, could be used to support drug development for pediatric cancers, and that there be more targeted use of disease foundation funds for drug discovery and development. She stressed the gap between government and foundation funding for research that generates data on promising drug targets, and the pharmaceutical and venture capital funding of clinical trials based on those discoveries.

Baber became aware of that gap when her 15-month-old son was diagnosed with a brain tumor. At that time she and her husband both conducted basic research on the DNA damage and repair pathways that can determine cancer susceptibility, and they were advocates for the precision medicine approach that this research suggests is possible. They were shocked to discover a lack of biomarkers available for clinical use that could help them decide the best treatment for their son, even though researchers had published papers on potentially useful biomarkers.

To bridge that gap over what some called the “valley of death” in the development pathway, investigators need access to more tumor samples with linked patient outcome data, as well as venture philanthropy and appropriate industry incentives to validate the biomarkers and potential drugs that had been discovered, Baber suggested. “There’s a huge gap between a promising discovery and a clinical trial, especially for children, and that gap is widening as the economy has suffered earthquakes,” she said. Closing that gap will require collaboration among all stakeholders, including patients and families, clinicians, funding agencies, philanthropic organizations, academic research institutions, the pharmaceutical industry, regulatory agencies, advocates, policy makers, and payers, she stressed.

Reaman also suggested there should be more patient-focused drug development, in which the benefits of treatments are also measured by how they reduce disease-related symptoms and enhance function in daily life, rather than simply focusing on length of survival. Smith stressed this as well, noting that current legislative incentives and industry paradigms for drug development are not patient focused and do not foster the conduct of the clinical trials that may be most needed for specific patient populations. Instead of asking what is the best clinical trial for a given drug, researchers should

be thinking about the most important therapy question that needs to be answered for a given cancer patient population, he said. This is especially true for rare pediatric cancers in which the number of patients available for clinical trials is limited, he pointed out. “We need to think about the key factors associated with treatment for a specific population—the key short-term and long-term issues that diminish quality of life or quality of survivorship—and based on that, determine the most promising clinical research opportunities we could explore for that patient population,” Smith said.

INTEGRATING PEDIATRIC PALLIATIVE CARE: ENSURING CHILD AND FAMILY WELL-BEING ALONG THE CONTINUUM

A key focus of the workshop was the integration of palliative care throughout the pediatric cancer care continuum to improve quality of life as well as survival. For children and their families, treating the pain, symptoms, and stress of cancer is as important as treating the disease (Kaye et al., 2015; Levetown et al., 2001; Schwantes and O’Brien, 2014). Pediatric palliative care lessens physical, psychosocial, emotional, and existential suffering and focuses on improving quality of life for both the child and family. It is appropriate at any age and any disease stage and should be provided along with curative treatment. While palliative care may be delivered by oncology practitioners, they may ask for the help of a specialized team of physicians, nurses, social workers and other professionals who work with them to provide an extra layer of support addressing the child’s and family’s specific quality-of-life needs. Pediatric palliative care specialists also help parents and children have a voice in realizing their treatment goals.

While earlier studies have repeatedly demonstrated the frequency and intensity of children’s suffering from symptoms like pain, breathlessness, fatigue, anxiety, sadness, and other forms of distress resulting from rigorous cancer treatments, unpredictable setbacks, and repeated invasive procedures, parents and health care providers are not always aware of extent of the affected child’s suffering. One study found that about half of cancer patients ages 7 to 12 who completed a questionnaire reported experiencing fatigue and about one-third reported having pain. Nearly half also reported being worried or nervous. When their parents were asked to fill out the same survey on behalf of their children, 43 percent rated their child’s pain or distress differently than the child did (Patel et al., 2011). Another study found that 89 percent of children who died of cancer experienced substantial suffering

in the last month of life and that there was significant discordance between the parent and physician reports of the child suffering (Wolfe et al., 2000a).

Addressing these concerning findings, evidence emerging over the past decade has firmly established the importance of pairing palliative care, including psychosocial support, with oncology treatment for adults and children in all care settings throughout cancer treatment and across the continuum of survivorship. Palliative care is also naturally aligned with other interventions such as cancer rehabilitation that focus on treating specific impairments and improving function as well as alleviating symptoms. Together, these integrated services offer vital support for maintaining patient and family quality of life during and after disease-directed treatment. As such, multiple professional organizations and accrediting entities have now endorsed early integration of palliative care to improve the quality of care for all seriously ill adults and children across the full trajectory of care (AAP, 2000; ACS, 2014; CoC, 2012; IOM, 2003b, 2015; Levetown et al., 2001; Smith et al., 2012; WHO, 2015).

Despite recognition of the importance of palliative care for pediatric patients, health care professionals have been slow to implement recommended pediatric palliative care in their practices and institutions, according to Lori Wiener, co-director of Behavioral Science Core and director of the Psychosocial Support and Research Program in the Pediatric Oncology Branch of the NCI Center for Cancer Research. One study found that the two main barriers to pediatric palliative care integration were ineffective communication (including about palliative care) between health care providers and families, and a lack of resource alignment with patient and family needs (Kassam et al., 2013).

Generalist Plus Specialist Palliative Care

A large majority of health care providers lack formal education, training, or experience in pediatric palliative care or in providing care for children at the end of life, said Wiener. Several participants stressed the importance of supporting initiatives for training and increasing access to both generalist- and specialist-level palliative care in pediatric oncology programs, and making these essential services available in all settings where children receive cancer care—whether inpatient, ambulatory clinic, or at home. Training needs noted for physicians, nurses, social workers, child life specialists, and other professionals specifically included enhancing communication skills (such as discussing prognosis, goals of care, and care

transitions), pain and symptom management, sensitivity to cultural and spiritual beliefs, as well as grief and bereavement care.

Generalist palliative care involves the basic management of pain, symptoms, and communications (e.g., discussions of prognosis) that every oncology clinician should be able to provide, while specialty palliative care is provided by a specially trained team who may be consulted for difficult-to-manage symptoms, complex family dynamics, or challenging care decisions, particularly when the first level of palliative care still leaves the patient or family suffering (Quill and Abernethy, 2013). Both levels of care can and should coexist, support each other, and expand palliative care delivery, said Chris Feudtner, the Steven D. Handler Chair of Medical Ethics and director of the Department of Medical Ethics at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. He added that this is particularly important in caring for children, because not all children’s hospitals have pediatric palliative care teams and the number of specialist-level pediatric palliative care practitioners available is not sufficient to manage the palliative care needs of all seriously ill children in all care settings. “It is something that is added and does not supplant the primary team, but rather complements what they are doing and often can be delivered concurrently with disease-directed therapy,” he said.

End-of-Life Care and Bereavement Care

For children with cancers that are not responsive to treatment, high-quality pediatric end-of-life care (such as hospice care) is needed. These services may be available via a free-standing hospice facility, a hospital, or at home, but many workshop participants stressed that such care must be accessible to all families where they live. More than 3,000 hospices in the United States currently will provide end-of-life care for children, but there is a dearth of free-standing, pediatric in-patient hospice programs, Wiener reported. The first such program opened in California in 2004. Feudtner and Joanne Wolfe, director of pediatric palliative care at Children’s Hospital Boston and division chief of the Pediatric Palliative Care Service in the Department of Psychosocial Oncology and Palliative Care at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, also noted that many of these programs are understaffed or underfunded. For example, efforts to build a pediatric hospice targeting unmet end-of-life and respite care needs for children and families in Seattle5 have been stalled for lack of funding.

___________________

Unfortunately, even when hospice care is available in the community, it does not always adequately meet the specific needs of pediatric patients and their families. One father reported that the care his son received while he was at home, in his final days, was nowhere near the quality of care that he received while he was getting treatment. He explained that because the home hospice nurse assigned to his son’s care was trained only in adult care, she was not comfortable administering the pain medications prescribed for her pediatric patient to relieve his suffering. As a result, 7-year-old Evan died in his home experiencing excruciating pain, breathlessness, and associated anxiety—circumstances that were also extremely distressing for his parents (see Box 3). After hearing Gavin Lindberg’s story about Evan’s preventable suffering, as well as Gavin and his wife Wendy’s ongoing grief and distress in its aftermath, Wiener stressed that no family should ever be told they can have home hospice care for their child if they do not have a pediatric provider available to support them.

The death of a child has a profound and lasting impact on the entire family. Bereavement care is provided to help support coping and recovery for the surviving parents and siblings after a child dies. Bereaved parents have been shown to be at increased risk for prolonged grief, isolation, potential economic and health decline, and behavioral health and emotional concerns, Wiener reported (Rosenberg et al., 2012). One study of parents whose children had died of cancer between 6 months and 6 years ago found that 40 percent of the parents expressed the need for bereavement services, but were not receiving any. More than one-third had received such service, but had dropped out because they believed the therapist did not understand them. In another study, nearly half expressed a need for bereavement services 2 to 4 years after the loss of their child (Lichtenthal, 2015). However, screening for bereavement needs, if it is performed at all, is usually only done within the first year after the death of the child, Wiener noted. “After a child dies and a family leaves the center where the child was treated, they are at home without any of us except for an occasional phone call,” she pointed out, adding, “There is a real drop in services that is unconscionable to me.” One parent shared that after his son’s death, the hospice nurse “was more interested in collecting and accounting for the oral pain medications that we had in the house than in comforting us or even sticking around to wait until the funeral home arrived.”

BOX 3

Parent Reflections on Suffering

Three parents who had lost children to cancer spoke about their experiences and provided personal perspectives on the suffering they witnessed and experienced firsthand.

Jennifer Cullen’s daughter Alexandra was diagnosed with medulloblastoma in 2011, just shy of her 4th birthday. She suffered 13 months of debilitating procedures before her death. Her treatment led to extensive and unrelenting mouth sores, severe sepsis when she was neutropenic, and finally, a seizure that led to blindness, muteness, and complete incapacitation. Cullen also described the worst horrors she and her husband endured as parents: “The realization that [Alexandra] would die. Zipping up a white body bag. Purchasing a pink coffin. And then having to carry on with life and raise a son.” At the workshop, just 3 years after her daughter’s death, Cullen courageously expressed a sense of hope, purpose, and determination that the collective experiences of the families of children with cancer will matter. “Because of what we have gone through, there is an enormous determination among all of us that we will make this matter—that the cancer knowledge and delivery of care can and should improve, including palliative care,” she stressed.

Gavin Lindberg’s son Evan was 3 years old when he was diagnosed with neuroblastoma and 7 when he died from his cancer at home. “There was not one day in those 4 years that Evan wasn’t either going through treatment or recovering from treatment. It was just absolutely brutal,” Lindberg said. Although Lindberg felt that Evan received excellent oncology care at Children’s National Medical Center, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, and The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and all three physicians who had cared for him at those institutions agreed that the best place for Evan to spend his final days was at home, his home hospice care was abysmal.

“I remember telling his end-of-life physician at Children’s National that our sole priority was to make sure that Evan did not suffer and was not in pain and was as comfortable as possible,” Lindberg said. But unfortunately, care supporting those goals was not provided adequately.

The end-of-life physician Evan had through Children’s National never met him before or after he started to receive hospice care at home. “The person who cared for my son at home when he needed it the most never met him and never spoke to him,” Lindberg stressed. In addition, he added, “The wonderful oncology nurses at Children’s National never had an opportunity to care for our son while he was at home. Instead we had nurses who came to see us from an adult hospital. Their experience and expertise was in caring for adults.”

Because the nurses were not comfortable administering intravenous pain medicines to pediatric patients, Evan was not given effective pain relievers and experienced extreme discomfort, distress, and anxiety. In addition, Evan had respiratory challenges that were not appropriately anticipated or addressed. When his end-of-life physician was called and asked to address these issues, the doctor said to expect Evan would live another week or two, but he died the next morning “after a horrific night that my wife and I will forever have seared in our memory,” Lindberg said. “Unfortunately, there are a lot of kids like Evan and that is just simply unacceptable in this country. Home was the right place for my son to pass, but what was wrong was the type of care he received. We put our trust and faith in the providers and in the system and that was a mistake on our part. There was a lack of communication. There was a lack of transparency about what was happening and why. Children with cancer fight too hard every single day to be left with a fate like that. If we can’t get this right, then shame on us. The hospice system failed our son and as a result, we feel like we failed our son. Those thoughts stay with you. On your worst days, they haunt you.”

Lindberg stressed the need to improve accessibility of high-quality end-of-life care for children at home. “Every terminally ill child in the home care setting should have the right to be cared for by doctors and nurses who have the experience and expertise in all key facets of pediatric hospice care to make these kids comfortable. I don’t want to hear about challenges with reimbursement, licensing challenges that prevent a physician and nurse to go from one jurisdiction to another and I don’t want to hear about funding issues. Because we can fix licensing, fund-

ing, and everything that is wrong with this system that made that little boy have his final days play out the way that they did,” he said. During the panel discussion, a participant noted that his daughter also received inadequate home hospice care until the adult nurse caring for her was replaced with a pediatric nurse.

Victoria Sardi-Brown lost her son Mattie, who had bone cancer, when he was 7 years old. Mattie died in the hospital. Throughout his 14 months of treatment, Mattie also experienced tremendous pain that was not validated and treated adequately by his practitioners. Nor did they ever use a distress thermometer or other assessment tool to gauge his degree of distress and pain. “Mattie’s death was so traumatic and his pain was so enormous that he had to be put into a coma to die,” Sardi-Brown said. The Browns’ experience led them to create the Mattie Miracle Cancer Foundation, whose goal is to create and implement a national standard for psychosocial care for children with cancer and their families from time of diagnosis, throughout treatment, into survivorship or end-of-life and bereavement care. “Integrating psychosocial care and palliative care is vital along the entire cancer care trajectory for positive outcomes. Cancer care is much more than just about the medicine. It must integrate psychosocial distress and pain management needs of the patient to be effective,” Sardi-Brown stressed.

Otis Brawley of the American Cancer Society underscored the importance of these moving personal testimonies that so glaringly reveal the shortcomings of cancer care for children and their families. “These stories will hopefully bring more awareness of the problem, which will require momentum to address. Big momentum comes from parents with personal experiences talking to people on Capitol Hill who have been elected. We can give them the true numbers and a book that summarizes all of the problems, but ultimately it is the parents of the kids and the kids talking that get these people to care,” he said.

Although conversations about a child’s cancer are difficult to have with parents, such communication is considered key in identifying and helping to allay the psychological and physical problems they are experiencing. Jennifer Mack, co-director of the Pediatric Hematology/Oncology Fellowship Program at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, stressed that communication allows for the development of shared knowledge between the practitioner and the child and family. It also can relieve distress and uncertainty and provides supportive care by building a therapeutic relationship. “Talking and listening are some of the most important things we do. Communication creates an opportunity for thoughtful decision making based on the personal values of parents and children,” Mack said.

Because of the worry that relaying bad news may cause distress and take away the hope of patients and their families, many clinicians avoid opportunities to communicate and wait for patients or parents to ask for information instead of offering it, or speak in euphemisms or offer overly optimistic information, according to Mack. That could help explain why one study found that more than 60 percent of parents of children with cancer were overly optimistic about their children’s prognosis relative to what the doctor reported (Mack et al., 2007a). In the end-of-life setting, parents of children who ultimately died of cancer tended to recognize that the child had no realistic chance of cure more than 3 months later than the physician did (Wolfe et al., 2000b). Brawley added that physicians may not convey bad news to parents “because sometimes it is hard for the doctor to accept that the patient is dying.” But parents who understand that their children have a poor prognosis are more likely to have do-not-resuscitate orders in place and use less cancer-directed therapy at the end of life, suggesting that this understanding of prognosis impacts the kinds of decisions that patients and their families make about care, Mack said (Wolfe et al., 2000b).

Although it seems counterintuitive, honest communication of bad news can not only be helpful, it can also relieve distress, Mack explained. Her studies show that parents of children with cancer consider communication about prognosis to be very important to them and helpful to decision making, even when they also find it upsetting, and parents who feel they have too little information about prognosis are actually those most likely to feel upset. Strikingly, parents who receive more extensive prognostic information are also those who report feeling the most hopeful, even when the child’s prognosis is poor. Prognostic disclosure is also linked with a greater

peace of mind and with greater trust in the physician (Mack et al., 2006, 2007b, 2009).

Although these findings can be puzzling at first glance, Mack pointed out studies that show uncertainty is distressing and makes people fear the worst. Honest communication can relieve that uncertainty and distress (Mack et al., 2006, 2007b, 2009). “Parents and children are worried about these issues, whether or not we address them. If we address them, we can help manage those fears and also correct misconceptions,” she said. She stressed that “When we communicate about difficult subjects, we also affirm that we will be with the parent and the child through tough times, and parents who know what is ahead feel more prepared to be there for their children. Ultimately, promoting false hope is not a goal of medicine, but being with patients and families through hard times is.”

Victoria Sardi-Brown, the parent of a child who died from cancer, noted that it was a nurse, not a doctor, who pulled her aside to tell her that her child was dying. “If I and my husband had understood what his medical trajectory was, then I would have felt more empowered as a parent to make better decisions for him. Once I found out we were dealing with end-of-life care, I did have hope. Hope changes along the continuum. When hope for a cure went out the window, then we hoped for a more sound, humane, and less painful death,” she said. “Empowerment and communication go hand in hand.”

Such communication and empowerment is important at the end of life, but families should be having conversations with their providers early on about care options and planning for their children, said Wolfe. She added that “sometimes it is really the child that gets empowered, and when the child becomes empowered, that helps empower the parents.”

Wiener also stressed the importance of doing care planning soon after diagnosis to help ensure treatments are aligned with patient and family goals. Both advanced care planning and palliative care are associated with positive outcomes, she noted, including care consistent with patient preferences, better quality of life, less distress, and longer survival. Adolescent patients are often capable of doing such planning and appreciate the opportunity, Wiener found, and she published ways to assess the readiness for such conversations and how to engage the patients’ families in such discussions (Wiener et al., 2013).

Wiener developed an advanced planning guide for adolescents and young adults called Voicing My Choices.6 The guide considers issues critical

___________________

6 See http://www.agingwithdignity.org/voicing-my-choices.php (accessed May 29, 2015).

in their development stage, including identity, autonomy, the importance of family and friends, how they want to be remembered, how they find meaning in their life, and their spiritual thoughts. The guide “allows youth to be able to document decisions that bring them peace and comfort,” Wiener said. Since the guide was first published in October 2012, patients have requested more than 20,000 copies, “which speaks to the need for a tool to open up these conversations,” she said. A recent IOM report also recognizes the importance of such conversations and recommends a life-cycle model, in which advanced care planning occurs at key developmental milestones, including when a life-limiting illness is diagnosed (IOM, 2015). This plan should be revisited periodically by both patient and providers and should become more specific as changing health status warrants.

Listening is another key component of provider communication and the ability of health care practitioners to administer effective palliative care, Mack stressed, as it builds the therapeutic relationship and gives patients and their families the opportunity to explore what is important or what is lacking in their care. “This sets the stage for formulating the goals of care,” she said. Helpful questions include those that ask patients and their families to contemplate the future and indicate what is most important to them and what they are most worried about, as well as what hopes they have; parents are asked what it means to them to be a good parent in the situation they are facing (Feudtner, 2009; Feudtner et al., 2015; Hurwitz et al., 2004).

When a child’s cancer is incurable, many providers rely on goal-oriented decision making as an important way to make decisions about care, but such decision making is needed throughout the child’s illness and can help the transition to end-of-life care, Mack said. “Making goals a part of decision making from the time of diagnosis can help us learn what matters to the parent and the child, and care can be framed in the context of these goals,” she stressed. One study found that clinicians often reach a decision about the preferred direction of care and then present it to parents, but parents often wish for a more active role in care decisions (de Vos et al., 2015). Parents also often seek options beyond what is offered by the oncologist, who needs to listen to those options before making recommendations, Mack said (Bluebond-Langner et al., 2007).

Wiener pointed out that one reason effective communication about palliative care is often not provided is because palliative care suffers from an identity problem—many clinicians mistakenly equate palliative care with end-of-life care and hospice (Parikh et al., 2013)—and the majority of health care practitioners lack formal skills training to be comfortable in

providing pediatric palliative care (Wiener et al., 2015b). Most pediatric oncologists learn to give such care by trial and error (Hilden et al., 2001), with 71 percent of pediatric hematology/oncology fellowships lacking training in palliative care (Roth et al., 2009), Wolfe reported. Nurses also often lack training in pediatric palliative care, she added (Pearson, 2013).

Parents frequently are not knowledgeable about palliative care or misunderstand it as appropriate only at the end of life when cure is not possible. Building on consumer research commissioned in 2011 by the Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC) and the American Cancer Society (CAPC, 2011), the American Childhood Cancer Organization (ACCO) adapted some of the poll questions to ask parents of children with cancer about their palliative care knowledge. As with the CAPC poll, few parents in the ACCO survey were knowledgeable about palliative care, but the majority (86 percent; Kirch and Ullrich, 2014) confirmed they would want it for their child when palliative care was defined as care focused on quality of life for the patient and family that manages the pain, symptoms, and stress of serious illness and can be provided along with curative treatment, Wiener noted.

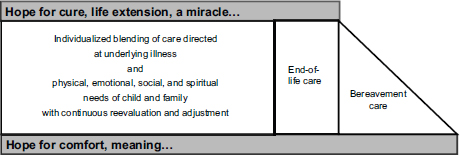

“We need to not think of palliative care as an on–off switch, but as a dimmer switch where palliative care is given alongside potentially curative treatments—a continuum where palliative care plays a role in each particular moment of the patient’s disease or cancer journey,” Wiener said (Tsai and CPS, 2008). Wolfe presented a model of pediatric palliative care delivery across the care continuum (see Figure 1), and added, “Palliative care enhances well-being and strength and resilience, and all of that is needed in order to be able to have the reserve to undergo cancer treatment successfully.”

FIGURE 1 Model of pediatric palliative care delivery across the care continuum.

SOURCE: Wolfe presentation, March 9, 2015.

Emerging evidence supports the notion that pediatric palliative care is beneficial to children and their families, Wolfe reported. Pediatric cancer patients who received this care were more likely to have fun (70 percent versus 45 percent) and to experience events that added meaning to life (89 percent versus 63 percent) (Friedrichsdorf et al., 2015). Children receiving pediatric palliative care also experience shorter hospitalizations and fewer emergency department visits (Ananth et al., manuscript in preparation). In addition, families who received palliative care for their children with cancer report improved communication (Kassam et al., 2015). When children with cancer and their parents are accurately told what palliative care offers, most indicated they would want to meet a palliative care team around the time of diagnosis (Levine et al., 2015).

However, despite the need for pediatric palliative care, few facilities adequately provide it, Wolfe noted. Contrary to American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) policy, which recommends broad availability of pediatric palliative care services based on child-specific guidelines and standards (AAP, 2000), only 58 percent of COG member institutions have access to a pediatric palliative care service (Johnston et al., 2008). Nearly one-third of children’s hospitals lack a pediatric palliative care program, or if they have one, they are often understaffed (Feudtner et al., 2013). Another study found that only 3 of 15 valued elements of palliative care were accessible to the families of children with cancer (Kassam et al., 2013).

Several studies done by Wolfe and others have documented that there is insufficient relief of the pain and suffering of pediatric cancer patients, even at facilities that offer robust palliative care. Most children in the last month of life suffer from pain, fatigue, and difficulty breathing, according to the reports of parents (Wolfe et al., 2000a). Another study found that most children with advanced cancer reported experiencing pain, fatigue, and other symptoms that were linked to high distress levels.

Feudtner stressed that pain medications can be effective. “At least half the time we are asked to do palliative care consults that improve pain management by using the available medicines more skillfully,” he said. But he added that “the availability of medications that we would like to be able to use is restricted by formulary restrictions.” Wolfe noted, “We are complacent as providers and as families—we expect that because these children are getting cancer treatment, they have to experience all of this distress. We haven’t challenged ourselves to raise the bar and to raise parent expectations that we can do better.”

Policy Opportunities to Improve Pediatric Palliative Care Across the Care Continuum

Several workshop participants suggested various policy measures that could improve access to high-quality pediatric palliative care across the care continuum, including developing standards and incentives for such care, educating health care providers and parents about palliative care, and providing more funding for and research on such care. Wiener pointed out the need for more evidence-based standards in pediatric palliative care, noting that there is only one standard, which is supported by 36 studies: “Youth and their families should be introduced to palliative care concepts to reduce suffering throughout the disease process regardless of disease status” (Weaver et al., 2015, p. 9). “Evidence-based standards are needed, but just as important are the policies and funding to help implement them,” Wiener said, adding “the most beautiful, heroic evidence-based interventions can go from the lab bench to the park bench if we don’t have systematic [implementation]. The same is true for standards.”

Peter Brown, co-founder of the Mattie Miracle Cancer Foundation, also called for the development of standards for palliative care and psychosocial support, similar to medical standards of care. He suggested that the federal government should deem this care as essential and mandate coverage through the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), saying that eventually, insurance companies would likely follow the CMS lead. He also suggested that accreditation entities for health care institutions should require screening for psychosocial needs.

Wiener suggested that core competencies in pediatric palliative care be implemented in schools of medicine, nursing, social work, psychology, and counseling. Feudtner called on medical schools to train physicians in practicing kindness, and imbuing them with a sense of duty and responsibility around kindness.

Parents also need to be educated about pediatric palliative care and how it can help them and their children throughout the care continuum, Wiener pointed out. Once they are aware of what palliative care offers, few parents would turn it down, she said. “If a child comes in with a cardiac condition, do we say to the parents, would you like to go to the cardiologist? No, we make the referral right away because we want the child to have the very best care possible. Similarly, I don’t know of very many parents, who when told by a physician ‘I want to make sure your child gets the very best care,’ would turn down palliative care,” Wiener said. Wolfe added that there are family

education guides and resources relevant to palliative care that should be offered to parents, including those that prepare them for having a conversation about the child’s potential death, so when the child asks “Am I going to die?” they know what to answer. “These different guides and conversation tools can be taught and handed to families so they don’t live in fear of being asked that question,” she said.

Wiener suggested integrating a palliative care service into pediatric oncology practices, but noted, “One does not need to have a palliative care service to integrate palliative care concepts, such as paying attention to symptoms, personal goals and values, and quality of life throughout care and extending beyond the hospital into the ambulatory and home setting.” She suggested taking a team approach to palliative care and relying on psychosocial oncology professionals, including social workers, psychologists, psychiatrists, and child life specialists, who are trained in providing palliative care throughout the disease trajectory and into survivorship. “We can’t work in our individual silos or we will get absolutely nowhere—we are better together,” she said.

Several participants also called for more research on pediatric palliative care. Feudtner observed that there is a huge gap in what is known and what needs to be known in this area. Wolfe said one study found that the key gaps center around knowing what matters most to parents and their children receiving palliative care, defining the best practices in pain and symptom management, implementing effective strategies in alleviating suffering, and identifying the bereavement needs of families (Steele et al., 2008). Another study provided the basis for consensus on 20 pediatric palliative care research priorities thematically grouped into decision making, care coordination, symptom management, and quality improvement (Baker et al., 2015). “The research needs are vast,” Wolfe said, and stressed that families are often willing to participate in such research. Mack also stressed the need to support research on the most effective communication techniques to use when providing pediatric palliative care.

Several participants pointed out the lack of funding for pediatric palliative care programs. “Many of the pediatric palliative care teams that are operating in different children’s hospitals are doing their work with a promissory note. We need to move beyond that and build vibrant pediatric palliative care programs at all centers with a good business plan underneath,” said Feudtner. Lindberg added, “I don’t want to hear there is no funding because that isn’t helpful to a parent who is facing losing their child tomorrow or the week after. It is too important not to be supported.” Reimbursement

strategies are also needed for the advanced care planning and other conversations health care providers have with their patients and families as part of their palliative care, Mack said. “These are time-intensive conversations that take place over and over again during the span of treatment.” She also noted that support is needed for programs that train practitioners on how to have those conversations.

Wolfe noted public policy and other incentives to increase pediatric hospice options, including a Massachusetts palliative care program that embeds pediatric teams within hospice programs throughout the Commonwealth that has “raised the bar in terms of access to home-based hospice care,” she said. Other states, such as California and Florida, have Medicaid waiver programs that enable enhanced pediatric hospice care in the home setting, she added. “Although the numbers are small, the ripple effect is vast, and we need these home-based programs to be able to take care of our children in the highest possible quality,” she said.

PSYCHOSOCIAL CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES

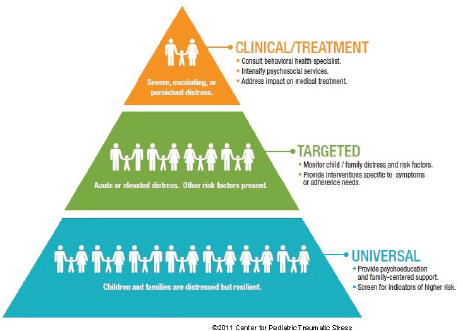

From the time of diagnosis onward, cancer poses many psychosocial challenges for a child as well as for his or her family, including anxiety over treatment or the possibility of dying, the stress of dealing with demanding treatments, and school and peer issues. Workshop participants discussed the psychosocial needs of children and their families and provided examples of ways to predict and screen for distress as well as interventions to alleviate distress. Participants also discussed standards of psychosocial care, capacity for providing that care, and research needs.

Mary Jo Kupst, Professor Emeritus at the Medical College of Wisconsin, gave an overview of some of these psychosocial challenges, beginning with diagnosis when there can be stress from information overload, with families expected to make rapid treatment decisions so the child can quickly begin treatment. In addition, both the patients and their families are navigating a new environment with new staff, especially if care occurs away from their communities. Even if families remain in the same town, they are spending an inordinate amount of time away from their homes and in the hospital with their children, who are receiving painful or distressing procedures with disturbing side effects. Despite all these pressures, “Cancer doesn’t occur in a vacuum and life still goes on and you have to deal with family, school, social changes, activities, work, and finances,” Kupst said (Kupst and Bingen, 2006; Kupst and Patenaude, 2015a,b; Rodriguez et al., 2012).

Once treatment becomes more routine, “families have told us this is a time when their emotions start bubbling up so that becomes a very difficult time as well. There are also physical changes, adherence challenges, school and peer issues, and an overall increased strain on the family because the pressures on them do not stop, but just keep going,” Kupst stressed. Ending treatment is a positive time, she noted, “but many families tell us that it is a loss of a safety net and support that you had almost on a daily basis for a long time as you transition to other and new providers” (Wakefield et al., 2011).

Survivorship requires continued monitoring of health status for the late effects of treatment that can disrupt life plans and goals. Surviving cancer can affect academic, vocational, social, and spiritual pursuits, Kupst pointed out (CCSS, 2015). When relapse and recurrence occurs, there is more treatment and uncertainty and a greater threat of death and difficulty maintaining hope. This is especially true once the child progresses to end-of-life care. “Families have told us that there was so much optimism at diagnosis, but once the child is dying you have to anticipate reality—the loss of your life if you are the patient, or the loss of the child if you are the parent. Parents need to talk and support children through this stage when they themselves are trying to deal with it and face the possibility of life after the child’s death, and trying to make sure that the child will be remembered. There is a need for comfort and support during and after this time,” Kupst stressed.

Psychosocial Needs for Pediatric Patients

How pediatric patients react psychologically to a diagnosis of cancer and the subsequent treatment depends on their developmental stage, Kupst noted. “There’s no one-size-fits-all reaction,” she said. Very young children have a number of issues they have to cope with, including fear of separating from their parents or of having painful or frightening treatments. In response to these stresses, their behavior can change and regress. They may attempt to control what they cannot control, have tantrums, cling to their parents, exhibit aggressive behavior, or withdraw from social interactions, Kupst said. Thus, she said the need for psychosocial support varies greatly among pediatric patients, and interventions should be targeted to the needs of individual patients.

Disruption of school is one of the biggest strains on school-aged children. Eric Sandler, Courtesy Associate Professor in the Division of Hematology/Oncology at the University of Florida College of Medicine,

Jacksonville, and a parent of a child with cancer, noted he had to take his daughter out of the public school system and enroll her in a private school because “no matter what we did, we couldn’t get the services that she needed,” despite having an Individual Education Plan developed based on her needs. School-aged children also experience a loss of peer interactions and activities while undergoing treatment, as well as distress over various procedures to which they are subjected. These older children have a greater understanding of the seriousness of their cancer and may seek emotional and social support. One parent of a 7-year-old diagnosed with cancer noted that after undergoing major treatments that put him in a wheelchair, he suffered from depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder.

Adolescents have many of the same issues as younger children, Kupst pointed out, with the addition of the strain the cancer is placing on their quest for independence at this stage. “Adolescents are thrown back into a dependent relationship with their parents and with the medical and oncology staff. Adolescent emotions are intense anyway, but this need for independence makes it doubly hard,” she said. Adolescents with cancer have an increased need for and use of social support, and are more focused on identity issues and image. They tend to use humor, self-talk, diversion, and positive reappraisal to cope with the stress of having cancer, but can also exhibit risk-taking behavior, according to Kupst (Kupst and Bingen, 2006).

Cancer in young adults may postpone, interrupt, or alter their romantic relationships and academic or vocational pursuits. They tend to have more concerns about how the long-term effects of cancer will affect their careers, fertility, and finances, Kupst said. Their coping strategies are similar to those of adolescents with cancer, she added, although more research is needed in this regard.