3

Million Hearts: A National Public Health and Health Care Collaborative

The Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO) Million Hearts State Learning collaborative was discussed as a model of a successful, nationwide collaboration between health care and public health. Million Hearts was launched by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) in 2011 with the goal of preventing 1 million heart attacks and strokes by 2017.1 Moderator Paul Jarris of ASTHO opened the panel discussion with brief comments about the infrastructure necessary to support a national collaborative. Guthrie Birkhead, deputy commissioner for New York State Department of Health, described the New York State experience with the Million Hearts collaborative. Joseph Cunningham, vice president of health care delivery and the chief medical officer for Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Oklahoma, then shared his perspective on what would motivate payers to participate in an initiative such as Million Hearts. Box 3-1 provides an overview of session highlights.

ASTHO MILLION HEARTS STATE LEARNING COLLABORATIVE

The ASTHO Million Hearts State Learning Collaborative began with a conversation with the director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) about forming a collaborative to focus specifically on

______________

1 See http://millionhearts.hhs.gov (accessed June 18, 2015).

BOX 3-1

Key Themes of the Session on the Million Hearts Initiative

- The Association of State and Territorial Health Officials Million Hearts Learning collaborative used an assessment tool to ascertain partners on their understanding of the shared vision, their leadership in their sector, engagement in the partnership, communication, and reporting and evaluation (Jarris)

- Drivers of quality improvement include

- committed leaders, multiple sources of data, standardization of protocols and tools (Birkhead, Cunningham, Jarris)

- finding community and clinical resources and linkages, identifying financing opportunities (Birkhead)

- Crucial role of pharmacists in communication and education, data sharing (e.g., two-way electronic communication that informs provider when a prescription was filled), and promoting adherence to hypertension treatment (Birkhead, Cunningham)

- Because Million Hearts yielded rapid and measurable results, could serve as a model for future collaborative initiatives that appeal to insurers (Cunningham)

rapidly improving hypertension, Jarris said. The goals of the ASTHO learning collaborative are to

- improve hypertension control and to achieve the national Million Hearts goal;

- identify and build networks and cross-sector partnerships to control hypertension;

- test models of collaboration between public health and health care;

- reintroduce a quality improvement (QI) process to affect practice and policy at all levels of the system; and

- focus on systems, sustainability, and spread.

The collaborative used National Quality Forum (NQF) Measure 18 as its measure for controlling hypertension. As described by NQF, this is a measure of the percentage of patients, 18 to 85 years of age, who had a diagnosis of hypertension and whose blood pressure was adequately controlled during the measurement year. An early challenge was that many clinical systems could not measure NQF 18, and many health departments were not familiar with NQF 18 or with the NQF measures system more broadly.

A multipartner assessment tool was used to ensure that the collab-

orative had the necessary partners from public health, clinical medicine, insurers and payers, hospital systems, and others, Jarris said. Starting with evidence-based best practices and strategies for identifying, improving, and controlling hypertension, partners were assessed on the extent to which they understood the vision; were providing leadership in their sector; were engaged as partners; were in communication with others; and were reporting back data and evaluation to support action.

Key Components of QI-Driven Impact

Traditionally, public health agencies are funded for finite, disease-specific programs, Jarris noted. The approach of the learning collaborative was different in that the goal was to bring the public health and health care systems together for the long term and to consider issues such as policy, spread, and sustainability. Jarris highlighted the importance of leadership and partnerships to the success of the learning collaborative and listed five key drivers of QI-driven impact:

- Leadership commitment across the health system at local, state, and national levels;

- Identifying community and clinical resources and linkages, such as team-based care delivery systems, faith-based outreach programs, healthy lifestyle promotions, and skills development for chronic disease self-management;

- Using multiple data sources to inform action;

- Using standardized protocols in areas such as hypertension management, community screening and referral, and equipment calibration; and

- Identifying financing opportunities, including private and public payment and federal and state grants.

A significant barrier, Jarris said, was the broad notion that electronic health records (EHRs) are sufficient for population health management. He added that very few EHR systems have a built-in registry, and those with a registry are not being actively managed (e.g., proactively calling patients in). Another challenge is that the clinical sector often thinks of public health as a regulator and does not understand public health’s interests or why they would want to work together.

Outcomes

In 2013, 10 states were selected to participate in the ASTHO Million Hearts Learning Collaborative. Since then, other states have been added,

with experienced states mentoring the new states to shorten the learning curve. During the first year, there were more than 250 “plan-do-study-act” or PDSA pilot testing cycles, four multistate meetings, and 69 peer group virtual convenings. Across the 10 states there were more than 150 partners and stakeholders involved, including payers, hospital systems, quality improvement organizations, Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs), local public health departments, community partners, state public health departments, health informatics, paramedics, and nontraditional partners. During the first year, about 89,000 people were reached, and Jarris said it was expected that those 10 states would reach 1.5 million people over the next year.

Jarris highlighted several of the key outcomes thus far. In the first 9 months, several clinics demonstrated improvement in the percentage of patients with hypertension under control by as much as 12 percentage points. One New Hampshire clinic, for example, improved control rates in its hypertension registry from 64 to 73 percent in 7 months. In addition, all 10 states reported that this project affected their other CDC-funded chronic disease work and influenced their approach to chronic disease. Six of the states said that their work with Million Hearts informed their Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) State Innovation Models (SIM) Initiative applications.

Standardizing protocols resulted in new diagnoses and increased control. For example, Washington, DC, clinics diagnosed close to 4,000 new patients; New York reduced its undiagnosed patients from 7 percent to 4.7 percent among reporting FQHCs, and hypertension prevalence increased an average of 4.8 percent (range 1.7 percent to 14.2 percent). Data collection has also improved. Ohio enrolled more than 7,300 patients in its registry in 3 months. Participating clinics in Minnesota can now pull NQF 18 data from their EHR systems and report it to the Minnesota Department of Health, and all FQHCs in New Hampshire began reporting on NQF 18 to the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services.

The project has also spurred innovative partnerships, Jarris said. In Vermont, for example, libraries lend out blood pressure cuffs. A clinic in New Hampshire is using some of its community benefit dollars to support registry managers in primary care practices.2 Screening and referral protocols are being implemented in community settings such as faith-based organizations, barbershops, and fire departments. Alabama is working with its military bases for screening and referral, and Oklahoma is partnering with the Choctaw Nation health system.

______________

2 The New Hampshire clinic (Keene) is using hospital (Dartmouth Hitchcock) community benefit dollars to support the registry management.

Challenges

Jarris summarized some of the challenges in sustaining and spreading successful models of population health improvement, including implementing a QI approach; understanding and intervening along the full health system, rather than using a programmatic approach; using data to drive action; building a public health workforce skilled in health system transformation; and identifying resources to sustain and spread models of success. Many good programs get started and then disappear at the end of the grant period, and Jarris expressed optimism that some of the CMMI SIM grants and CDC grants are being tapped to continue this work.

MILLION HEARTS COLLABORATIVE NEW YORK

The ASTHO Million Hearts State Learning Collaborative described by Jarris is a model for how to do collaborative work across the country, Birkhead said. Typically, CDC funds individual states, and those states with similar goals and objectives may occasionally meet at a national meeting and share their experiences. The ASTHO learning collaborative is unique in that it is a multistate collaborative, with ASTHO bringing states together and providing coordination and technical assistance.

Birkhead shared the New York State experience with the Million Hearts collaborative as a case example of the successful collaboration between public health and health care. The New York State Department of Health served as the lead organization and the convener of partners for the project. Other statewide partners included the Health Center Network of New York (a group of all FQHCs in New York using a single EHR package called eClinicalWorks); the state’s Quality Improvement Organization (IPRO, which conducted some of the data analysis); the American Heart Association; and the New York Health Plan Association. At the local level, three FQHCs and their corresponding county health departments participated (one rural, one urban, and one suburban). Other local partners included AmeriCorps workers and the Cornell Cooperative Extension (a group of agencies across New York that provide education and other services at the local level). One large regional health information organization, Hixny, was also engaged to analyze the health information exchange data for one of the participating counties (Albany) to conduct hypertension surveillance at a community level.

Programmatic and Data Innovations

The Million Hearts project aim in New York State, Birkhead explained, was to produce a 10 percent improvement in 1 year in hypertension control, using the NQF 18 measure. Several programmatic innovations con-

tributed to achieving this goal. The FQHCs used the Institute for Healthcare Improvement model3 to implement system changes via PDSA cycles to improve hypertension control. Each of the FQHCs established clinical treatment protocols. Birkhead noted that two of the clinics adopted the CDC-recommended clinical treatment protocols for hypertension, which meant that care was standardized across the two clinics. The FQHCs implemented system changes in how they process patients (e.g., changing the exam room layout to allow for blood pressure measurement without having the patient move or stretch). A home blood pressure monitoring program was also implemented. Patients received automated blood pressure monitors and education materials developed by the AmeriCorps collaborators and the county health departments.

Data collection was a major component of the project, and Birkhead highlighted several innovations that came out of the Million Hearts project. As mentioned by Jarris, there are challenges with the functionality of EHRs for data collection, and Birkhead said that the software package the FQHCs were using could not easily function as a registry. Because the three FQHCs were using the same EHR software (eClinicalWorks), the Health Center Network of New York was able to provide data extracts that essentially functioned as a hypertension registry (albeit not in real time). The New York State Department of Health and the Health Center Network of New York developed and piloted a measure of undiagnosed hypertension. The measure captures patients who have elevated blood pressure on two different occasions within 1 year who do not have a previous diagnosis of hypertension.

Another area of focus was hypertension medication adherence. The Medicaid Datamart was used to identify medication adherence rates in the clinics with mixed success, Birkhead said. One approach was to look at the proportion of days covered by an antihypertensive prescription medication, which Birkhead said is technically feasible, but very resource intensive. A second measure was primary non-adherence (i.e., not promptly filling a prescription); however, there was no real-time access to pharmacy prescription fill data.

The final example of a data innovation was hypertension surveillance at a population level. This was done in one county, using the regional health information organization (Hixny) health information exchange data. The surveillance pilot looked at overall hypertension prevalence, the measures of hypertension control, and undiagnosed hypertension in a community. The value of a health information organization, Birkhead said, is that it can pull data from different EHRs, and

______________

3 See http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/HowtoImprove/default.aspx (accessed June 18, 2015).

they do not have to be using the same record system. On the other hand, the data arrives in different formats and may or may not be usable for a specific purpose.

Project Outcomes

Birkhead briefly shared some of the data from the project. Prevalence of hypertension across the three health centers ranged from 29 to 40 percent at baseline (center average of 33.5 percent). Although the variation could reflect differences in how the centers were measuring blood pressure and detecting hypertension, he suggested that this baseline likely reflects the actual underlying rates of hypertension in the populations served. Within one year, the prevalence had increased slightly (center average of 35.3 percent). The goal was not to increase hypertension prevalence, he clarified, but to get a true measure of hypertension in these communities. Prevalence in two communities did not increase by much; however, in the third community, there was a net increase of 11 percent. Undiagnosed hypertension rates ranged from 6 to 8 percent at baseline, which Birkhead said was lower than expected. One year later, undiagnosed hypertension was reduced 5.5 percent overall, a net 19 percent reduction from baseline. At baseline, hypertension control (using the NQF 18 measure) ranged from 52 to 70 percent (center average 56.9 percent). One year later, hypertension control had increased by more than 10 percent from baseline at each FQHC, with hypertension control ranging from 50 to 80 percent across all three communities.

Lessons Learned

Birkhead offered a list of lessons learned from the New York State experience with the Million Hearts collaborative:

- Cross-sector collaboration with various partners was key to success.

- Senior leadership involvement at all levels in all systems was essential.

- Clear, consistent communication generated a common understanding.

- Efficient use of patient registries for planned care accelerated improvement.

- A common EHR platform across the FQHCs was critical.

- It was helpful to develop new metrics. For example, the newly developed and tested undiagnosed hypertension metric was successful in identifying patients in need of further evaluation.

- The FQHCs regarded highly their collaboration with their local public health departments. Coming together around a common goal has additional benefits since the project.

- The project demonstrated the ability to achieve improvement in hypertension control in a very short time frame.

Birkhead reiterated some of the specific roles of public health at the state and local levels. At the state level, senior and executive leaders from the New York State Department of Health were engaged, which he said was significant in getting support and interest in participation across the ranks within each of the partnering systems. The state also has resources to support the initiative; directs and serves as convener; aligns with other state initiatives; has connections as the Medicaid and managed care operator in the state; can provide true population-level data; can promote the use of evidence-based strategies; and spreads innovation to other initiatives.

At the local level, a key factor was the engagement of the county health departments as members of the FQHC quality improvement teams. The local health departments were integral partners in implementing the home blood pressure monitoring strategy, providing education to patients around blood pressure monitoring techniques and following up to measure the increase in knowledge and skills around self-monitoring of blood pressure and uptake and satisfaction with the program.

Opportunities for Improvement

A number of opportunities for improvement were identified, and Birkhead shared several brief examples. The first suggestion is to enable prescribing of a 90-day supply of hypertension medication to increase medication adherence. Although not a Medicaid rule in New York, most of the managed care plans restrict prescriptions to a 30-day supply out of concern about cost and waste (e.g., paying for a 90-day supply, only to have the patient switched to a different medication). Birkhead suggested that once a patient is on a stable regimen, he or she could be switched to a 90-day supply per prescription refill. Some data show that adherence is decreased with a 30-day supply because people do not or cannot keep up with refilling prescriptions.

Another area for improvement is two-way electronic communication when a patient fills or refills a prescription. The Medicaid pharmacy claim system allows Medicaid to know when a prescription is filled in real time; however, that data does not get back to the provider. Birkhead noted that there is a major initiative in New York to develop a statewide health information network (SHIN-NY) and to create data-sharing agreements so that data can flow in both directions. There are other opportunities to build

better two-way communication. In New York, for example, a managed care plan is notified when its patient goes to the emergency department, but the provider is generally not notified.

Next Steps

The next step for the Million Hearts initiative in New York State is expansion. Birkhead highlighted two CDC grant programs that the state is tapping to continue and to spread the initiative. The Health Systems Collaborative program grant (CDC 1305) will be used to expand to 9 FQHC/local health department collaborations, with 63 clinic sites by 2018. The focus will also expand to include diabetes control and prediabetes identification. The State and Local Chronic Disease program grant (CDC 1422) will be used to improve the data exchange between the regional health information organization and the FQHC data warehouse, working to overcome EHR differences and improve alerting and communication functions.

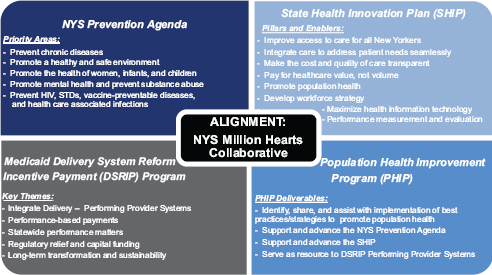

Million Hearts came at the right time, Birkhead concluded. The focus and strategies of the Million Hearts collaborative are well aligned with those of other current initiatives of the New York State Department of Health to improve health and transform health systems (see Figure 3-1). These initiatives include, for example, the New York State Prevention Agenda–State Health Improvement Plan; the State Health Innovation Plan–SIM grant; the Medicaid Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment Waiver Program; and the Population Health Improvement Program.

PAYER AS PARTNER: BLUE CROSS AND BLUE SHIELD AND THE HEARTLAND OK MILLION HEARTS PROJECT

The Health Care Service Corporation operates five Blue Cross and Blue Shield (BCBS) plans in Illinois, Montana, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas and is the largest customer-owned payer in the United States, and the fourth largest payer of any kind, said Cunningham. In his role as vice president of health care delivery and the chief medical officer for BCBS of Oklahoma (BCBSOK), Cunningham has the opportunity to engage with the other four states as well. With this broad perspective, he discussed why the largest payer in Oklahoma would want to participate in initiatives such as Million Hearts.

Heartland OK

The Million Hearts project in Oklahoma is called Heartland OK and is fundamentally a care coordination model focused on blood pressure control and medication adherence, he explained. The program is available

FIGURE 3-1 Alignment of the New York State Million Hearts Collaborative with ongoing New York State Department of Health initiatives to improve health and transform health systems.

NOTES: HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; NYS = New York State; STD = sexually transmitted disease.

SOURCE: Birkhead presentation, February 5, 2015.

in five contiguous rural counties in South Central Oklahoma. Patients are referred to the program from any primary care provider. Heartland OK partners with the health departments and utilizes their care coordinators and educators to provide routine blood pressure checks and give information about physical activity, stress management, diet and nutrition, and other topics that a primary care provider does not usually have the time to go over. The program also enlists the support of community pharmacists to assess medication adherence. (Cunningham noted that on joining BCBS, he was struck by the number of people who do not fill the prescriptions from their doctor.) Patients graduate from the program when blood pressure control is met (as outlined in NQF 18 or a goal set by the primary care provider).

Why BCBSOK Participates in Heartland OK

Million Hearts appeals to BCBSOK because it supports its mission to improve health for all Oklahomans, not just BCBSOK members, Cunningham said. As a partner, the plan is able to leverage its strong relationships with providers across the state to support quality improve-

ment projects, especially in rural communities. BCBSOK wanted to provide incentives to people and providers to participate in health. As part of the Blue Cross Association, BCBSOK has access to large amounts of claims data. These data, he explained, can be used to provide insight into the incidence of hypertension in targeted counties and into medication adherence and incidence of cardiovascular events in adherent and nonadherent populations. BCBSOK was also interested in linking its claims data with clinical data through a state health information exchange. A health information exchange can provide a more robust picture of plan members/patients, assist with treatment planning, and potentially reduce redundancies in care. Finally, BCBSOK saw participation in Heartland OK as part of its responsibility to the community. The organization wants to develop strong public–private partnerships and work together with all entities that are paying for care (even competitors) to align programs.

Cunningham highlighted several opportunities that BCBSOK saw in participating. The majority of the plan’s members are in rural communities, and participation in Million Hearts supports the development of quality incentive programs (e.g., referrals to and graduation from Heartland OK; improved blood pressure control and/or medication adherence). Participation also provides a unique opportunity for public–private collaboration in the development and expansion of value-based care models in rural Oklahoma. Finally, Heartland OK promotes participation in the state health information exchange, MyHealth Access Network. The exchange aggregates all of the datasets collected by anyone who touches a patient and creates actionable data that are accessible at the point of care for use in treatment planning and care management. Robust, aggregate data help to facilitate accurate diagnosis, decrease redundancies, reduce costs, improve outcomes, and increase patient satisfaction, Cunningham said.

Topics highlighted during the discussion with participants included the importance of being patient centered in establishing goals and conducting outreach; regional variations in programs; the diagnosis and prevalence of hypertension; the application of the Million Hearts model to other initiatives; and issues around data and data systems.

The Importance of Engaging Patients and Their Providers

A participant noted the importance of asking patients what they need and asked how patients and plan members were engaged in the work

of Million Hearts. Birkhead concurred that engaging patients is key to any medical endeavor. Each of the three community health centers in New York engaged with patients in a different way. The home blood pressure measurement, for example, presented an opportunity for a community health worker to engage patients personally about their own needs. Cunningham stressed the importance of education because people with hypertension do not necessarily feel sick, especially early on, and often do not understand the importance of taking their medication. Panelists also highlighted the importance of asking patients what medications they are taking or why they are not taking their medications, reiterating that the data on whether a prescription is ever filled does not usually make it back to the prescriber.

Jeffrey Levi of Trust for America’s Health asked about lifestyle interventions associated with Million Hearts. Jarris said that a number of the states were using the Stanford model of self-management, an evidence-based program to foster an individual’s self-efficacy around his or her condition.4 Others conducted community outreach around lifestyle, such as cooking classes or shopping guidance. Some faith-based organizations, particularly churches, looked to changing the foods served at church functions.

Ron Bialek with the Public Health Foundation raised the issue of clinician perceptions and attitudes. For example, clinicians may think that patients are noncompliant in the strict sense when, in fact, they may be facing issues such as choosing between purchasing their medications or food, the inability to take time off from work for appointments, or other barriers to compliance. Cunningham said it can be a challenge to go into a practice and tell the staff to manage select patients a certain way. Bring clinicians to the table, share data that their patients with hypertension are not refilling prescriptions, and ask how best to help improve their patients’ blood pressure control. New York worked with FQHCs, and Birkhead said the leadership in those centers was key to the success of the effort. It is not about providers or patients being good or bad, but about fixing the system, Jarris added. There will always be noncompliant patients, but the true percentage is low. The rest are being missed in the system with regard to detection or management. Cunningham recommended aligning focus on what is best for the patient. Patient-centered goals and expectations foster buy-in across the spectrum of care.

______________

4 See, for example, http://patienteducation.stanford.edu/programs/cdsmp.html (accessed May 7, 2015).

Regional Variations

Participants discussed the need for different programs in different regions. Jarris pointed out that Million Hearts did not prescribe what was done but provided guidelines. Birkhead noted the need to go through the same collaborative processes with each new site, such as gathering all of the stakeholders, getting buy-in, getting contributions, and identifying resources in the community. Some generalities about rural areas might be used to jumpstart the effort, but the collaborative start-up processes cannot be bypassed completely. Cunningham concurred, adding that any program, whether rural or urban, starts with getting all participants to the table. Historically, payers would go to providers and tell them what they needed, instead of asking them what problems they had and what they thought they needed. The better approach is to align incentives and strengthen relationships.

The Diagnosis of Hypertension

Kate Perkins of MCD Public Health in Maine asked whether improved accuracy in blood pressure measurement could have had any impact or implications for assessments of hypertension prevalence. Million Hearts found that many clinical settings do not calibrate their blood pressure cuffs or equipment, Jarris said, and there were initiatives to help support calibration. The protocols also specifically dealt with how blood pressure was measured. The biggest problem, whether in the clinic, the fire department, or the church, was people not sitting for the required period before their blood pressure was taken.

Marthe Gold from the City College of New York raised the potential issue of overdiagnosis and overtreatment, given the heterogeneous approach to diagnosing hypertension, from clinical office to home visits to borrowing blood pressure cuffs from the library. Jarris responded that optimally, a hypertension protocol would have a period of assessment that included dietary, activity, or other lifestyle modifications before any treatment. There may be people who are overdiagnosed, but the bigger problem is the 50 percent with a diagnosis whose condition is not controlled.

Pamela Russo of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation asked about the use of registries for patients with comorbid diseases. Birkhead said that New York is working to add diabetes and prediabetes to the registry. An EHR system needs to have a registry function that can cross different diagnoses in the same patient. The registry is not a big database of everybody with hypertension, he said, but a distributed network that has all of the data in it.

The Application of the Million Hearts Model to Other Initiatives

Ted Wymyslo, who was former director of health in Ohio, pointed out that public health is not accustomed to initiatives, such as Million Hearts, that have new definitions of measurement and short timelines seeking rapid outcomes. Should we expect to see more of this type of rapid effort, he asked, or are the initiatives useful only in certain situations? Jarris responded that the particular topic (hypertension) was selected because there was a lot of interest to drive intervention and change in how it is managed. It happened to be hypertension this time, but it could have been something else, he said. The initiative was introduced to change thinking, for example, to get leadership to quickly implement programmatic and policy initiatives to drive rapid cycle change, to develop measurement systems to drive action, and to not wait for a perfect system or one that reports data that is years old. Birkhead said that the task now is to take what was learned from Million Hearts and apply it more generally in public health. The success of the approach needs to be publicized. A major change, Jarris added, is moving from collecting data for historical recording purposes to collecting good-enough data to drive action. Cunningham said that approach appeals to private payers because they do not like that it can take several years before an outcome can be observed. Payers like rapid return on investment.

George Isham of HealthPartners also asked about moving beyond a single-topic national priority toward a set of initiatives driven more scientifically by careful epidemiological analysis. Jarris reiterated that hypertension was the test case used to build the collaborative and test the model. If we can learn how to use this model and how to support it, he said, then states and communities can select the most appropriate measure for use in their situation.

Data

Sanne Magnan from the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement noted that the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology has released a 10-year vision to build interoperable health information technology and asked what advice Million Hearts might offer them. Birkhead said that the vision does involve public health more so than in the past, and is building the population health view into EHR systems. A problem during the Million Hearts initiative was the reporting of transactional data that could not be entered as a measure of hypertension in a registry. The system has to change so that the data can be aggregated at the regional level or population-based level. EHR systems need to be able to produce documents that can be used for population health. Cunningham agreed and said there is a need to mandate interoperability

of EHR systems. Birkhead reiterated the need for reverse flow of data (e.g., getting data on prescription fills back to the provider). It is not just about aggregating data at the population level but also feeding data back. A public health agency with access to data across systems can identify hot spots of disease, Jarris added.

One problem, Jarris suggested, is that there is not a business case for EHRs for population health. The current business case for EHRs is essentially capture of claims and improved billing, not for the registry function or their ability to improve population health. He expressed hope that SIM grants will create a demand for tools in EHR that will support population health or that it will be mandated in a certified EHR. Cunningham added that the value of data comes in sharing it, and we need to move beyond the concept of “my data.”

Levi asked whether there was any comparative effectiveness analysis done across the entire Million Hearts initiative. Jarris explained that finding researchers willing and able to conduct analyses of the effects and outcomes of health policy interventions is a challenge common across many interventions, including ASTHO’s Healthy Babies initiative and various prescription drug interventions implemented across various states.

This page intentionally left blank.