2

Collaborating to Advance Payment Reform

The first case example considered at the workshop was on the topic of payment reform, defined in the Health Affairs blog as “payment methods that reflect or support provider performance, especially the quality and safety of care that providers deliver, and are designed to spur provider efficiency and reduce unnecessary spending” (Delbanco, 2014). The session’s moderator, Rear Admiral Sarah Linde, chief public health officer at the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), referred participants to a recent blog post by Sylvia Mathews Burwell, Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), titled Progress Towards Achieving Better Care, Smarter Spending, Healthier People (Burwell, 2015a). In the post, Secretary Burwell said that significant progress had been made over the past several years, thanks in large part to the Affordable Care Act (ACA), and discussed how to build on that progress and take it to the next level. As summarized by Linde, Burwell described setting clear goals and establishing a timeline for moving from volume to value in Medicare payments and using benchmarks and metrics to measure progress and be accountable for reaching those goals. This is noteworthy, Linde said, because this is the first time in the history of the Medicare program that HHS has set explicit goals for alternative payment models and value-based payments.

The first goal is that by 2016, 30 percent of all Medicare provider payments should be in alternative payment models that are tied to value, rather than volume. The next target is to reach 50 percent by 2018. Examples of such models are accountable care organizations (ACOs), the patient-centered medical home (PCMH), and bundled payment models.

The second goal is for all Medicare fee-for-service payments to be linked to quality and value, with targets of at least 85 percent in 2016 and 90 percent in 2018. This goal can be accomplished through programs or models such as hospital value-based purchasing and hospital readmissions reductions programs. Linde noted that Burwell discussed making these goals scalable beyond Medicare. In the post, Burwell also announced the creation of a Health Care Payment Learning and Action Network to facilitate partnerships with private payers, employers, consumers, providers, states, state Medicaid programs, and other partners to expand alternative payment models into their programs.

Linde also highlighted the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI, or the Innovation Center) at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), which is testing an array of alternative payment models and service delivery models through demonstration and pilot programs. For example, the State Innovation Models (SIM) Initiative funds states to develop innovative linkages between advanced primary care and public health through avenues such as financing data exchange, integration, performance monitoring, and others.

Following the introduction by Linde, Theodore Wymyslo, chief medical officer of the Ohio Association of Community Health Centers, and Mary Applegate, medical director of the Ohio Department of Medicaid, discussed health care transformation and payment reform in Ohio as an example of successful collaboration between health care and public health organizations. Box 2-1 provides an overview of session highlights.

BOX 2-1

Key Themes of the Session on Payment Reform

Payment reform in Ohio:

- Requires paying for value, care coordination, alignment of efforts (Applegate, Wymyslo)

- Is linked with system transformation and has been informed by a Governor’s Advisory Council on Healthcare Payment Reform that includes five major insurers covering 80 percent of the population (Wymyslo)

- Has been facilitated by Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation grant and Medicaid expansion (Wymyslo)

- Has required buy-in and support of public health staff and collaboration among public health agency, health care organizations, and other partners (e.g., state employees’ insurance plan) (Wymyslo)

- Has required a shift to patient-centered medical homes and a combination of episode and population-based payment models (Applegate)

HEALTH CARE DELIVERY SYSTEM AND PAYMENT REFORM IN OHIO

You cannot have payment reform unless you have health care delivery system reform, Wymyslo began, and he provided a brief timeline of the activities related to the transformation of health care in Ohio. This transformation involved the coming together of public health and clinical medicine, which he noted are not accustomed to working closely together. At the time, however, several regional collaboratives in Cincinnati, Cleveland, and Columbus were diligently working on regional health transformation. In addition, the Cincinnati and Cleveland collaborative had been selected as one of seven regions in the country for the Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative by CMMI.

In January 2011, Ohio Governor John Kasich issued an executive order establishing the Office of Health Transformation and bringing state health agencies (Medicaid, Health, Aging, Mental Health, and others) under unified leadership. In February 2011, Wymyslo was appointed director of the Ohio Department of Health and was directed to expand the PCMH model statewide. The four main priorities for improved health for the state of Ohio included expanding PCMH across the state, curbing tobacco use, decreasing infant mortality, and reducing obesity. He noted that it was very different for public health leadership to be engaged with PCMH expansion. In July 2011, the Office of Health Transformation issued its innovation framework, a three-part approach to modernize Medicaid, streamline health and human services, and pay for value.

As he traveled around the state, Wymyslo identified the need for a mechanism to allow people to exchange information on a regular basis, and in November 2011, the Ohio Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative was established. This forum, which currently has about 850 members, engages all interested parties in discussion about the variety of changes needed around the state (members include payers, providers, patient advocates, patients, and others). The collaborative, facilitated by the Ohio Department of Health, is the venue for moving forward with the various partners around the state in a collaborative way, Wymyslo said. It coordinates communication among existing PCMH practices, facilitates statewide learning in collaboration with these practices, facilitates the start-up of new PCMH practices, and helps shape policy for statewide PCMH adoption.

In March 2012, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) report on the integration of public health and primary care was released, which Wymyslo said helped to energize the ongoing work in Ohio (IOM, 2012). In July 2012, the Ohio Patient-Centered Medical Home Education Pilot Project was funded and initiated. Wymyslo noted that the project was conceived in 2009 and signed into law in June 2010, but despite full support to move this new

model of care forward, it remained unfunded due to budget deficits. By partnering with Medicaid, Wymyslo was able to identify ways to fund the pilot project to train 44 practices in the PCMH model. Insurers were also considering ways to participate collectively in paying for care coordination, outcomes, and value, and in January 2013 the governor created the Governor’s Advisory Council on Healthcare Payment Reform. The council brought together the five major insurers that covered 80 percent of the population in the state of Ohio, as well as many of the large health care delivery system leaders, many of the medical associations, and patient advocates and patients. The following month, Ohio received a planning grant from the CMMI SIM Initiative. In January 2014, Ohio expanded its Medicaid program under the ACA, and in December 2014, the state received a CMMI SIM Initiative Testing Grant for $75 million. To date, Ohio has made good progress with practices being able to achieve PCMH recognition, Wymyslo said.

In conclusion, Wymyslo said that a key lesson is to be sure that people understand what you are trying to achieve and why it makes a difference to them. For transformation of health care in Ohio, an important first step was ensuring that public health staff understood the importance of public health integration with primary care to be able to achieve meaningful change for the population they serve. This was especially important because there was no additional budget set aside, and these efforts had to be undertaken with existing resources. Without the buy-in and support of public health staff, the statewide success thus far would not have been possible, he said.

Collaboration, Cooperation, and Coordination

Applegate continued the discussion of the challenges of reorganizing to do a better job with the same resources. She shared data showing that 29 states have a healthier workforce than Ohio, yet Ohioans spend more per person on health care than all but 17 states. Ohio has perhaps the least healthy people at the highest cost, she said, and this was the impetus for reform.

The current health care system was designed to pay for sick care, Applegate said. Working together to make a difference in population health requires alignment at the front end. The planning process of a collaboration is very important to establishing common ground and goals. One reason a collaboration does not work, she suggested, is that partners cannot stop doing something that is not effective. This is often the case in a grant-funded environment, where an activity or approach must be carried out for the duration of the grant. Once the partners are aligned, the next steps are to design, develop, and implement a plan. The plan needs

to be focused on a population, she stressed, with specific measurement targets. The plan should be based on sound evidence of the best clinical practice and carried out in the context of public health and sociopolitical systems. Finally, it is essential to determine how to sustain the plan through value-based purchasing. Improving health is about collaboration, cooperation, and coordination, she continued. People who are cooperating often do not have the same end goal, but are part of the journey together, and coordination is really about communication. There is tension within this system, she noted. Moving too fast suggests that planners have not listened to the needs of the community, but moving too slowly means there is never any action.

Microsystems to Macrosystems

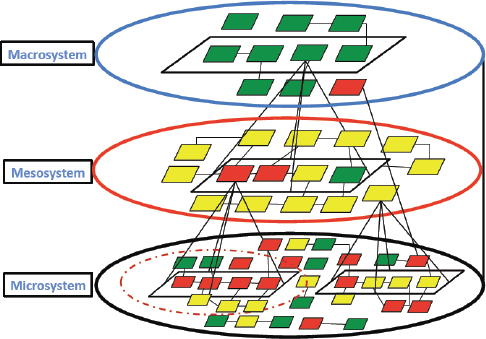

In the health system, microsystems are the building blocks that come together to form macro-organizations (see Figure 2-1). Much of the work at the microsystem level is not connected. For example, the person con

FIGURE 2-1 Collaboration, cooperation, and coordination. Microsystems are the building blocks that come together to form macrosystems.

SOURCE: Applegate presentation, February 5, 2015.

ducting Medicaid maternal and child health home visits is not necessarily connected to the family’s pediatrician or obstetrician. Applegate said that after decades of home visits and millions of dollars invested, there has been no improvement in postpartum visit rates or reproductive health for the Medicaid population. There is an opportunity to get the different programs to come together and align for a common purpose. Continuing with maternal and child health as an example, she suggested that there are opportunities in “preconception health,” which is really adolescent and adult woman wellness. Implementation of the ACA means that the role of public health as a safety net service for everybody who is uninsured is changing, as women and families now have access to care. There are also opportunities to align and makes progress on the identification of high-risk pregnancy and on postpartum health. There are communication barriers to alignment in the microsystem at the community level. For example, the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act limits the information that can be disclosed about students. Applegate suggested that better communication among staff in public health, health care settings, and schools could have a possible effect on suicide rates.

The mesosystem is made up of collections of microsystems, such as health systems, hospitals, or managed care plans. Elements of the microsystem, such as health clinics, are often under contract with or otherwise related to elements of the mesosystem. State- and national-level organizations comprise the macrosystem. What is needed, Applegate said, is alignment of both top-down and bottom-up strategies to identify priority populations and have all stakeholders participate in activities that move known measures and report on progress publicly.

Creating Systems to Improve Health Outcomes

Likening health to a pyramid, Applegate said that at the base are physical and mental health care, behavioral health/personal health decisions, education, and social determinants. Other countries invest more per person than the United States in the base of the pyramid, so they have fewer people at higher risk for health concerns (i.e., at the peak of the pyramid) (see, for example, Bradley et al., 2011). In an illness-based system, the costs are high, with ever-diminishing returns.

Applegate likened the emerging health system under the ACA to a relay race. The first runner is health care coverage; the next is smart use of data to target special populations; the third leg is addressing the disparate outcomes and issues of health equity at the neighborhood or local health district level; and the final runner is community coordination. No one wins, she said, until the final runner crosses the finish line, and it is the final coordination piece where there are often the largest issues. Commu-

nity coordination spans housing, transportation, access to medications, health literacy, individuals or populations at risk, workforce, faith-based communities, safety net services, and PCMHs, for example. Success is improved population health, she said.

Paying for Value

As mentioned by Wymyslo, at the end of 2014 Ohio received a CMMI SIM Initiative Testing Grant, and one area of focus was paying for health care value. Applegate reiterated that the payment reform initiative is a public–private partnership, including the five largest payers in the state, along with Medicaid, the state employees’ insurance plan, and numerous other stakeholders. A challenge to reform, she noted, is that many of the health plans are national, and they are not going to change a specific element simply because Ohio wants them to.

Applegate briefly reviewed the three approaches to coverage of care. The current fee-for-service payment system was designed to pay for discrete services correlated with improved outcomes or lower cost, Applegate explained. There is now a shift toward population- and episode-based payment. Episode-based payment covers acute procedures, inpatient stays, and acute outpatient care (e.g., newborn delivery, treatment of asthma). Population-based payment approaches include PCMH, ACOs, and capitation. This approach is most applicable for primary prevention for a healthy population and care for chronic conditions. Accurate outcomes measurement will be important as payment approaches shift toward new models, she said. In a fee-for-service model, only the people who show up for care are counted, and many others are missed, impacting overall outcomes measurements, she noted.

The 5-year goal for payment innovation in Ohio is to have 80 to 90 percent of the Ohio population in some value-based payment model. This effort involves a shift to PCMH and a combination of episode- and population-based payment models. In shifting to episode-based payment, the state is leading the effort to define episodes, including the episode trigger, episode window, claims included, principal accountable provider, quality metrics, potential risk factors, and episode-level exclusions (see Table 2-1).

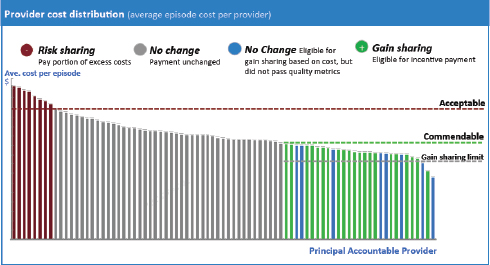

The process is based on retrospective thresholds that reward cost-efficient, high-quality care, Applegate explained. Patients seek care and select providers, providers submit claims, and payers reimburse for all services, as they already do today. After a 12-month performance period, payers calculate the average cost per episode for each principal accountable provider and provide a comparison to other participating clinicians around the state. On the basis of the results, providers may be eligible

TABLE 2-1 Elements of the Episode Definition

| Category | Description |

| Episode trigger | Diagnoses or procedures and corresponding claim types and/or care settings that characterize a potential episode |

| Episode window |

|

| Claims included | |

| Principal accountable provider | Provider who may be in the best position to assume principal accountability in the episode based on factors such as decision-making responsibilities, influence over other providers, and portion of the episode “spend” (i.e., cost) |

| Quality metrics | Measures to evaluate quality of care delivered during a specific episode |

| Potential risk factors | Patient characteristics, comorbidities, diagnoses, or procedures that may potentially indicate an increased level of risk for a given patient in a specific episode |

| Episode-level exclusions | Patient characteristics, comorbidities, diagnoses, or procedures that may potentially indicate a type of risk that, due to its complexity, cost, or other factors, should be excluded entirely rather than adjusted |

SOURCE: Applegate presentation, February 5, 2015.

for incentive payments if average costs are below a threshold and quality targets are met (see Figure 2-2). On the other hand, if average costs are above the acceptable level, providers may be required to pay part of the excess cost. There is no change in pay if costs fell in the mid-range or if costs are below threshold but quality did not pass metrics. Principal accountable providers will be able to access standardized Episode of Care Payment Reports through an online portal starting in 2015. In response to a question about how the threshold acceptable costs are defined and determined, Applegate said that the payers are allowed to determine the threshold. A question was asked about data collection for the measures that the providers agree to be rated on, noting that often the electronic health record (EHR) does not collect the data in a way that lends itself to

FIGURE 2-2 Retrospective thresholds reward cost-efficient, high-quality care.

SOURCE: Applegate presentation, February 5, 2015.

useful analysis later. Applegate said that the measures related to claims and feedback to practitioners are in need of improvement, and there are several multistate work groups related to EHR-derived measures, but work is in the early stages.

During the discussion that followed, participants and panelists discussed how to identify the challenges to collaboration, engage public and private payers, link to social services, work across state lines, and focus and streamline safety net services.

Challenges to Collaboration

To start the discussion, moderator Linde asked the speakers to identify the main challenges to collaborating. Wymyslo said that many people wanting to collaborate simply do not ask for help. He reached out to potential partners and explained that although he did not have the necessary resources, the issue was important to him and to them. He found partners that brought different resources to the table when they were asked, but he stressed that you have to ask for help. Knowing who to ask and who needs to be at the table can be a challenge, he acknowledged. In addition, partners must leave their pet projects at the door and enter

the collaboration ready to define and agree on common ground and stay focused until the end. Applegate likened collaboration to working with patients as a physician. It is about asking what matters to them, she said, meeting them where they are and finding out how to help them.

Money is also a challenge, and Applegate stressed that sustainability must be addressed at the start and should be more transparent. Time constraints also need to be made public, she added. Another challenge is group dynamics, especially when working with large groups. One approach that works, Applegate recommended, is to do a lot of listening in large groups. After the listening activities, a small group develops a draft for the others to provide feedback on. She reiterated the need to be transparent with timelines and processes and to use “parking lots,” where issues not immediately relevant can be set aside, but not forgotten, and addressed later.

Applegate said that in working to reduce infant mortality, Ohio has struggled with a lack of stability in leadership, confusion about measurement, and lack of understanding about the framework and process for moving forward. People tend to want to do what they have already done, she said. It is important to be explicit in saying that this is new work, not just a rebranding of something that was done 5 years ago.

In many cases, the challenge is getting started. Cathy Baase of The Dow Chemical Company asked about the origins of payment reform in Ohio and how to stimulate similar activities in other communities, counties, or states. Wymyslo said that the state was in a financial crisis and a health crisis, and being in crisis opens people’s minds to finding solutions. The governor had been developing plans for years about balancing the budget, and he brought people on board who wanted change to happen. Wymyslo said he personally became engaged because his former students, now family practice residents, told him that although public health was integrated into their clinical training, when they went into practice they could not implement it.

Bringing Public and Private Payers Together

Sanne Magnan of the Institute of Clinical Systems Improvement asked about bringing private and public payers together. Wymyslo responded that the state started by leveraging Medicaid, which covers more than 2.2 million Ohio patients, and the state employees’ insurance plan, which covers 500,000 state workers, to demonstrate that these payment reform principles work. The state then challenged other insurers to do the same thing. It is not just telling everyone what to do, but showing them what to do, Wymyslo said. A crucial factor, Applegate said, was the leadership at the level of the Office of Health Transformation and the involvement

of the governor. Another element was the investment by Medicaid in data analytics and sharing the data and analysis with private payers and clinicians. She noted that the financial officers of the institutions were not engaged until after the conversations on ideal clinical practice took place. Wymyslo added that another critical element was the existing high level of trust between stakeholders and the state, which was based on previous interactions to address opioid prescribing, infant mortality, and other health issues.

Linking to Social Services and Other Sectors

Participants discussed further the link between the clinical health care system and the social services system. Jeffrey Levi of Trust for America’s Health asked about establishing these connections and filling gaps in available social services. It is important to pick priorities that are feasible in that there is evidence for effective action, interest from the top as well as on the ground, and a measurement system to support the initiative, Applegate said. In Ohio, infant mortality meets all of these criteria. The state lags behind other states in addressing disparities in infant mortality. The single largest contributor to infant mortality is preterm birth, which is greatly influenced by maternal health. A number of clinical interventions are available, but taking these to scale in small communities is a challenge, she said, in part because of social determinants of health. Another cause of infant mortality, sleep-related deaths, is largely preventable, but it is a challenge getting information to people. Infant mortality is also the result of birth defects, infectious diseases, violence, and other causes.

Applegate described a life course measurement framework around which partners can come together. Process measures include adolescent well checks (i.e., preconception health), vaginal progesterone as an intervention for preterm birth, early elective deliveries, postpartum visits, safe sleep environments for infants, and social determinants (e.g., tobacco exposure). Partners, including public health, Medicaid, clinical/health systems, patients/families, and others (e.g., schools, community- and faith-based organizations, and employers) are asked what they could do in each of these areas. For example, what could an entity do to help adolescents be seen for well visits? Data are used to work with partners and strategically target efforts to specific neighborhoods (e.g., those with the highest preterm birth and low birth weight rates). Community health workers seek out at-risk women and provide opportunities for them to receive maternal care through Medicaid Managed Care. Applegate noted that information is captured in the case management systems of the managed care plans, so there is no need to invest in an entirely separate data

system. The key is to use existing systems to get to a different place with regard to data, transparency, and payment innovation, she said.

Applegate said that a current barrier to linking health efforts to social services is not having data about exact needs. Much of the information is anecdotal; however, there is now a data collection tool and plans to collect data on the social needs of priority populations (e.g., for affordable housing). Levi added that a challenge is getting data on social determinants of health to the clinician on the frontline of care. For example, a physician seeing a child in the office could potentially access data on the basis of the child’s zip code and know if the child lives in an area with high lead levels, low fluoride, a high crime rate, housing concerns, poor air quality, and so forth. These data exist, he said, but they are not readily accessible in the exam room where the provider seeing the patient can use them to make public health–informed recommendations to the patients who are there for a traditional clinical care. An added challenge is that clinicians are not trained to do this. He noted that Ohio House Bill 198 includes an imperative for curriculum reform so that students in the health professions learn about the need to consider social and environmental determinants of health. Applegate concurred with the need to change the way clinicians and allied health personnel are trained. In Ohio, a majority of clinicians will not see many Medicaid patients once they complete their training, she noted.

Karen Armitage, pediatrician and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Health Policy Fellow, raised the issue of measuring the costs of care linked to social determinants of health. For example, a young mother at a newborn check reveals her partner is incarcerated, she lost her job when she took time off to have the baby, and she is having trouble with breastfeeding. How will the episode of care payment report measure the cost of care in such cases?

An online participant noted that schools are a link in health care that is not being fully utilized to help identify those at risk and disseminate health messages. Applegate concurred that schools have a huge capacity to be able to impact health, but they are very tied to political systems, and there are legal concerns about the sharing of information.

Cross-State Collaboration

George Isham of HealthPartners raised the issue of fragmentation of both measurement and incentives across the states and the federal government. He asked about efforts by Ohio to align with neighboring states and whether there are regional issues that might be different from those elsewhere in the country.

As an example, Wymyslo said that Ohio has worked closely with partner states on issues of opioid prescribing. The prescription drug monitoring programs for the contiguous states now share information so that people near state borders, who may purchase medication in both states, do not escape identification and tracking.

Ohio and neighboring states in the Midwest also have high rates of infant mortality in common. Applegate commended the HRSA Collaborative Improvement and Innovation Network to Reduce Infant Mortality for working to bring the nation together and to learn from previous efforts. Wymyslo also commended the flexibility and fluidity of CMMI, which he said showed real innovation by allowing southwest Ohio to include northern Kentucky and part of Indiana as partners in the project. Health care is not restricted by state borders, and these are natural capture areas for patient care in that area.

Safety Net Services

George Flores of The California Endowment raised the issue of people who are continuing without insurance coverage, including undocumented immigrants. Applegate said that state programs can only be leveraged for those who are actually eligible for them. Safety net services from local health districts cannot be totally eliminated, but they could be focused and streamlined and could work with the other entities. Wymyslo said the state of Ohio has a strong network of free clinics, with thousands of volunteers who see people who are not eligible for the state programs. This may not be ideal, he acknowledged, but it is at least identifying people and bringing them into the system and, they hope, allowing them to connect to a more permanent health care solution. Flores noted that such safety net systems often do not capture data. Wymyslo said that the free clinic model does capture its own data but is not connected to a centralized database. He then noted that an even greater impact is delivered by Ohio’s community health centers, which deliver care regardless of a patient’s ability to pay. These centers currently provide care for 565,000 patients in 55 of Ohio’s 88 counties and are a very important part of the total health care delivery system. The free clinics often refer patients needing ongoing care to the community health centers, where the patients can receive continuous primary care services.

Roundtable and IOM Activities

Isham highlighted the importance of Secretary Burwell’s recent announcement, described by Linde in her introduction, and referred participants to a commentary in the New England Journal of Medicine (Burwell,

2015b). He also cited an article by Rajkumar and colleagues that lays out a framework for various payment reforms, and population-based payment is one of the categories of reforms described (Rajkumar et al., 2014, supplemental material). Isham added that the paper also discussed the notion of incentives for improved population health in general. He suggested that the nature of the recent communication from HHS provides an opportunity for the roundtable to think about how to use these developments and create a common conversation.

Linde pointed out that recurring themes throughout this panel discussion on payment reform were similar to the elements of success identified by the IOM for integrating primary care and public health (IOM, 2012). These themes included shared goals, community engagement, aligned leadership, a focus on sustainability, and shared data and analysis.