3

Flood Risk Management and a Precedent for a Community-Based Flood Insurance Option

Today in the United States, flood insurance is offered through the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) via individual policies. Community-based flood insurance (CBFI) is a theoretical concept that has been discussed within the flood risk management community, but has not been implemented as a policy option in practice. There are, however, several programs and opportunities for community-level1 participation in broader flood risk management, including those through the NFIP.

This chapter describes risk management and how it specifically applies to floods; already existing opportunities for community-level participation as the precedent for community-based options; and key flood insurance topics that include participation and flood insurance takeup rates, community involvement, communication of flood risk, flood insurance premium pricing, and socioeconomic factors.

The basic methods for risk management are applicable to managing flood risk and can be grouped into two categories: (1) risk control and (2) risk financing (Rejda and McNamara, 2014).

Risk control encompasses the methods of avoidance, loss prevention, and loss reduction. Avoidance means that a particular loss exposure is never acquired or undertaken, or an existing loss exposure is abandoned. For example, some flood losses might be avoided by ensuring that no new homes are built in locations where flooding might occur. Moving or abandoning homes in high-risk areas would be another approach to avoiding

_______________________

1 FEMA currently defines a community as a political entity that has the authority to adopt and enforce floodplain ordinances for the area under its jurisdiction (FEMA, 2015e).

flood losses. Loss prevention refers to measures that reduce the frequency of losses. In the context of flood risk, loss prevention could include the building and improvement of levees and seawalls and certain other aspects of floodplain management. Loss reduction encompasses measures to reduce the severity of a loss after it occurs. Certain floodproofing methods can be used to reduce the severity of flood losses for a home or building. In some instances, floodproofing measures might prevent a structure from flood damages.

Risk financing includes the techniques of retention, noninsurance transfers, and insurance. It may also include explicit transfers, such as aid. Retention means that the owner of a property (or a community) would retain part or all of the risk associated with flood losses. Noninsurance transfers refer to methods other than insurance by which a risk and its associated financial consequences are transferred to another party. It is unclear how this method could be employed for flood risk in a way that would serve public policy objectives. For example, if a homeowner intends to default on a mortgage because he or she cannot afford or would not plan to repair or rebuild a home damaged by flooding, this could constitute a noninsurance transfer of risk, but this strategy would arguably not be in the public interest. The public interest, in this context, is for housing costs to include the expected loss due to flood risk. Another example that could contribute to a similar result is a lender offering higher mortgage interest rates based on the assumption that a flood will result in loan default. In this situation, the higher mortgage payment is a mechanism to transfer risk. Finally, insurance can be used to transfer flood risk by which a property owner would be partially or fully indemnified for any flood losses by whatever entity or entities that provide the insurance (e.g., the NFIP, private insurance companies). Therefore, when a community considers managing its flood risk, it may consider many of the components described above, with insurance being one mechanism to protect against flood damage.

EXISTING COMMUNITY-BASED OPTIONS FOR MANAGING FLOOD RISK

Communities play a substantial role in flood risk management through a myriad of programs and actions. Community governance structures have unique authorities to administer land use and building codes, levy taxes, collect fees, generate revenue and use other opportunities to reduce or minimize the impacts of flooding. They are often recipients of resources provided by federal programs directed at preparing for, responding to, recovering from, or mitigating flood hazards. Of the programs related to flooding, some are directly linked to the NFIP, while others are tied to disaster and non-disaster programs outside the NFIP.

The following section highlights various ways communities can already participate in the NFIP and serves to illustrate the precedent for a community-based option. These examples include flood risk and floodplain management, the Community Rating System (CRS), the Cooperating Technical Partners Program, and the Flood Mitigation Assistance Program.

Flood Risk and Floodplain Management

Comprehensive flood risk management is a shared responsibility carried out at various levels, from the federal government to the individual. Federal-level activities include building and maintaining structures such as levees, floodwalls and dams; providing real-time flood information and forecasts; communicating flood risk and actions that localities and individuals can undertake to reduce flood risk; preserving or protecting lands that provide for natural storage of floodwaters; and administrating of the NFIP. State-level activities generally include coordinating the NFIP (every state has a designated office for coordinating the NFIP), establishing state building codes and sometimes directly permitting development, coordinating the FEMA hazard mitigation assistance grant programs (every state has a designated State Hazard Mitigation Officer), overseeing dam safety and sometimes levee safety, and undertaking or financing structural measures. At the community level, these same actions are possible, but other options exist through floodzoning and building codes, evacuation plans, and participation in the NFIP, including participation in the CRS.

The NFIP encourages the incorporation of flood hazards into land use decisions. In exchange for the ability of homeowners and businesses to purchase flood insurance from the federal government, communities that join the NFIP agree to adopt and administer the minimum standards, as specified in floodplain federal regulations (44 C.F.R. § 60.3). For example, when a proposal is made to develop within a flood hazard area, federal regulations are intended to minimize risk and flood damages. This means that the community must have the authority to implement and enforce land use and building codes. One NFIP program—the Community Assistance Program - State Supported Services Element (CAP-SSSE)—funds states that provide technical assistance to communities to help them meet their minimum floodplain management ordinances and evaluate their performance.

A 2006 multistate study found that when local governments prepare and implement comprehensive plans for urban development, insured losses from flooding (under the NFIP) are significantly lower than losses sustained by communities that do not adopt such plans (Burby, 2006). This 2006 study recommended several steps that the federal government could take to attract greater attention by local governments to the planning and regulation of urban development and a greater local government role in limiting

the adverse financial consequences of hazardous events. Most mitigation policy efforts are isolated and not integrated into the broader activities of local growth management (Lyles et al., 2014). This study demonstrated opportunities for coalition building among stakeholders by seeking ways to produce co-benefits such as habitat protection. Furthermore, the study showed that when mitigation is integrated into comprehensive plans, communities are more likely to adopt and implement regulatory policies aimed at mitigation.

Community Rating System

The Community Rating System is an incentive-based, voluntary program for NFIP communities, with the objective of reducing flood risk.2 FEMA implemented the CRS in 1990 as an incentive to communities to adopt more rigorous floodplain management strategies and increase flood awareness (FEMA, 2014a). To be eligible, a community must not only participate in the NFIP, but also be in good standing (e.g., no unresolved violations of floodplain management ordinance). The program uses a class rating system from 10 to 1 (1 being best) that offers a 5 percent reduction—and up to a 45 percent reduction—in NFIP flood insurance premiums, with each improvement in class for eligible properties in the Special Flood Hazard Area (SFHA). For eligible properties outside the SFHA, there are only 5 percent and 10 percent discounts. A community accrues credit points to improve its CRS class by engaging in activities such as public information and outreach, mapping and regulations, flood damage reduction, and warning and response. Starting in 2013, the activity of flood insurance promotion was officially added to credit communities that actively encourage residents and businesses to purchase and maintain adequate flood insurance.

Communities can also submit mitigation plans adopted under the Disaster Mitigation Act (DMA) (see Chapter 4 for further discussion on DMA) for CRS credit. A recent study of 71 local mitigation plans in Florida and North Carolina revealed no significant differences between floodplain management elements of hazard mitigation plans that received CRS credit from those that did not receive CRS credit (Berke et al. 2014). Furthermore, among five classes of mitigation policies (land use, structural protection of buildings, flood protection structures, emergency services, and information and awareness), emergency services were given most attention because they were politically the most expedient, did not threaten property values and tax base, and were easiest to administer, while land use policy was given

_______________________

2 Multiple CRS resources, such as a coordinator’s manual, CRS communities and their classes, number of CRS communities by state, and a national map are available at https://www.fema.gov/national-flood-insurance-program-community-rating-system.

the least attention. The 2014 report concluded that CRS offers promise, but recommended that emergency preparedness and response policies, and investments should not be given credit under the CRS.

Communities expend their own resources to prepare documentation, execute activities, and maintain programs to participate in the CRS; therefore, they have a demonstrated ability to successfully administer a complex flood risk management program. Direct benefits for the community’s investment are only offered through premium reductions to the individual policyholders. The premium reductions must be absorbed in the flood insurance policies administered elsewhere. Other benefits to the community include reduced flood risk through mitigation measures such as elevating structures above base flood elevation and retaining floodplain landscapes (Asche, 2014). Because participation in the CRS tends to be in communities that currently have a large number of flood insurance policies, they may also be motivated to participate in a CBFI option.

As of March 2014, about 1,300 communities were participating in the CRS. Although this represents a small percentage of the 22,000 NFIP communities participating in the NFIP, greater than 67 percent of all flood insurance policies were written in CRS participating communities (FEMA, 2014a).

Cooperating Technical Partners (CTP) Program and Risk Map

Another example of how communities participate in the NFIP is the Cooperating Technical Partners (CTP) Program and Risk Map. The CTP Program was developed in 1999 to increase involvement in the NFIP (for example, becoming a more active participant in the flood hazard mapping program) through partnerships with FEMA and regional agencies, state agencies, local entities, tribes, and universities. Main program objectives include maintaining national standards at the local level; provide training and technical assistance; and use data from local sources to help with floodplain management (FEMA, 2014b). There are about 22,000 active NFIP communities, and 240 communities, universities, agencies, and tribal nations have signed agreements with FEMA under the CTP Program (FEMA, 2015c). Under the NFIP flood risk mapping program, there is a NFIP-funded allocation for developing flood insurance rate maps (FIRMs) and a separate, congressionally authorized and appropriated program called the Risk Mapping Assessment and Planning (Risk MAP). Risk Map provides mapping and information to communities to help reduce their flood risk. Under a partnership agreement, roles and responsibilities are established and funding is provided based on eligibilities and agreed-upon activities.

Flood Mitigation Assistance Program

Our final example, which illustrates the precedent of how communities participate in the NFIP is the Flood Mitigation Assistance (FMA) Program. The FMA Program was created in 1994 to reduce the number of insurance claims. It supports mitigation efforts such as floodproofing, as well as rebuilding of property that received significant damage from a severe flood (NRC, 2015). The program provides funds through states, territories, and tribal governments to sub-applicants (communities, tribal agencies, state agencies, tribal governments) who are insured under the NFIP to reduce or eliminate the risk of flood damage. FMA grants can be used to plan projects or to help the grantee manage and administer the program. Funding is provided annually and states can submit projects based on FEMA guidance. The program is a 75 percent federal/25 percent non-federal cost share. In fiscal year 2014, $89 million was available to reduce claims under the NFIP (FEMA, 2014c). In fiscal year 2015, $150 million will be distributed (FEMA, 2015d).

This section discusses several key flood insurance topics within the NFIP: participating communities, policyholder participation and takeup rates, community involvement, communicating flood risk, flood insurance premium pricing, and some socioeconomic factors. Chapter 4 discusses some of these topics in terms of how CBFI may contribute solutions.

Participating Communities

For individual property owners to purchase flood insurance, the community in which the property owner resides must participate in the NFIP (FEMA, 2005a; FEMA, 2005b). The NFIP specifically defines a “community” as a governmental body—including cities, towns, villages, townships, counties, parishes, special districts, states, and Indian nations—with the statutory authority to enact and enforce development regulations (FEMA, 2005a). (See Chapter 4 for further discussion on the definition of community). From a federal perspective, community participation in the NFIP is voluntary. For a community to participate, it must adopt and enforce floodplain management regulations that meet or exceed the minimum requirements set by its state, as well as the NFIP (FEMA, 2005a; FEMA, 2005b). These requirements are meant to ensure that future development in the community will at least meet these minimum requirements and hence better protect the community from flood losses (FEMA, 2005b). In exchange for the implementation and enforcement of these floodplain management

regulations, as well as ongoing compliance with the program at large, every property owner in the participating community can purchase flood insurance coverage (FEMA, 2005a). A brief quantitative description of the policies-in-force for NFIP participating communities is presented below.

The following NFIP-participating community data summary is based upon the 2012 NFIP policy database provided to the Wharton Risk Management Center. For the year 2012, within the 50 states, a total of 18,391 NFIP communities were identified from this database encompassing 5.4 million total policies-in-force with $1.25 trillion in insured coverage (building and content) and $3.49 billion of earned premiums.3

In 2012, an average NFIP community had 295 policies-in-force with 68 percent of these being single-family residential policies, 22 percent other residential policies (including condominium units), and 5 percent each for multi-family and nonresidential occupancy policies. Across these 295 policies-in-force, an average of $68 million of total exposure ($54.9 million of total building and $13.1 million of total content) was insured in the community. Total earned premiums for this coverage was about $189,600 (see Table 3-1). Thus, for an average policy in an average NFIP community, $231 thousand of total exposure is insured ($186 building and $45 content) with an earned premium of $644 per year.4

NFIP communities (Table 3-1) are divided by location in a coastal5 or non-coastal state. The NFIP has traditionally had higher takeup rates in coastal communities (Dixon et al. 2006; Michel-Kerjan et al., 2012; Kunreuther and Michel-Kerjan, 2013a). Of the total 18,391 NFIP communities, 44% are located in a coastal state, but these communities represent 89 percent of the 5.4 million total policies-in-force. On average, each of the coastal states has 337 active NFIP communities, with 601 policies-in-force on average in each of these coastal communities (67 percent single-family, 5 percent multi-family, 23 percent other residential, and 4 percent nonresidential). Across these 601 policies-in-force, an average of $142.1 million of total exposure ($114.6 million of total building and $27.5 million of total content) was insured in the coastal community. Total earned premiums for this coverage was about $377,200 for the coastal community.

Although non-coastal states have a larger number of NFIP participat-

_______________________

3 Official statistics provided by the NFIP for 2012 are 5.6 million policies-in-force, $1.29 trillion of coverage, and $3.34 billion of earned premium. See https://www.fema.gov/statistics-calendar-year.

4 Please note these average values are not split by residential vs. nonresidential types which have different building and content coverage limits—250/100 and 500/500, respectively.

5 Coastal states include Alabama, Alaska, California, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Mississippi, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Texas, Virginia, Washington, and the District of Columbia.

TABLE 3-1 Average Policies-In-Force, Flood Insurance Coverage for Buildings and Contents, and Earned Premiums of NFIP Participating Communities in Both Coastal and Non-Coastal States

| Number of NFIP Communities | Average Policies-in-force | Average Total Building Coverage | Average Total Content Coverage | Average Total Earned Premium | |

| Coastal State | 8,076 | 601 | $ 114,557,556 | $ 27,531,624 | $ 377,209 |

| Non-Coastal State | 10,315 | 55 | $ 8,243,244 | $ 1,873,052 | $ 42,743 |

| Total U.S. | 18,391 | 295 | $ 54,928,818 | $ 13,140,445 | $ 189,616 |

SOURCE: 2012 NFIP policy database.

ing communities (on average each non-coastal state has 382 active NFIP communities), they support fewer policies-in-force, 55 policies-in-force on average (78 percent single-family, 4 percent multi-family, 7 percent other residential, and 11 percent nonresidential). Across these 55 policies-in-force, an average of $10.1 million of total exposure ($8.2 million of total building and $1.9 million of total content) was insured in the non-coastal community. Total earned premiums for this coverage was about $42,700 for the non-coastal community. Thus, for an average policy in an average non-coastal NFIP community, $183 thousand of total exposure is insured ($149 building and $34 content) with an earned premium of $775 per year.

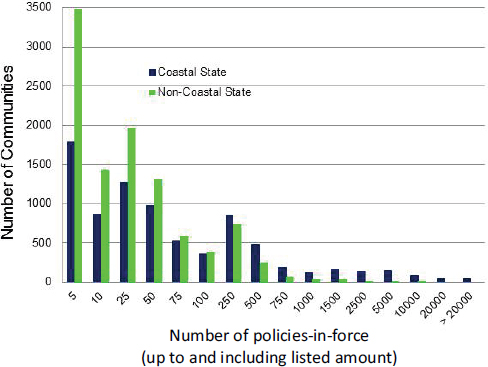

Figure 3-1 illustrates the complete distribution of the number of policies-in-force in each community split by coastal and non-coastal states. Both community policies-in-force distributions are skewed implying non-symmetry in participating community “size,” and thus making it more difficult to determine a typical average community size value as discussed above. In coastal states, 33 percent of communities have 10 or fewer

FIGURE 3-1 Number of NFIP-participating communities in coastal and non-coastal states plotted against the number of policies-in-force.

SOURCE: 2012 NFIP policy database provided to the Wharton Risk Management Center.

policies-in-force, with a median value of 27 policies-in-force, and a maximum value of 186,591 policies-in-force for a community in Florida. In non-coastal states, 48 percent of communities have 10 or fewer policies-in-force, with a median value of 12 policies-in-force, and a maximum value of 8,624 policies-in-force for a community in Arizona.

Overall, the data illustrate a flood insurance program that impacts a large number of NFIP-participating communities in different ways. For example, some participating communities have 100,000 or more policies-in-force, whereas a substantial portion (41 percent) of communities in the overall NFIP portfolio has 10 or fewer policies-in-force. Furthermore, this variation in community size and corresponding insurance coverage exists independent of whether a state is coastal or non-coastal. Thus, it is not a simple matter to define an average NFIP community, suggesting it may be complex to develop a one-size-fits-all community-based approach to flood insurance.

Policyholder Participation and Takeup Rates

During the early 1970s, only 95,000 NFIP policies were in place. The NFIP paid only $3 million in claims following Tropical Storm Agnes in 1972, even though total damages were estimated to be $3 billion (Anderson, 1974; FEMA, 2002). In response to this low level of takeup, Congress passed the Flood Disaster Protection Act of 1973, which directed federally regulated lenders to require flood insurance as a condition of granting or continuing a loan on structures in the SFHA (the mandatory flood insurance purchase requirement; see further discussion in Chapter 4). Even though takeup rates increased in general, in areas affected by the Midwest floods in 1993, only about 20 percent of structures were insured (Galloway, 1995). Congress subsequently strengthened the mandatory purchase requirement in the National Flood Insurance Reform Act of 1994. As described below, however, takeup rates still remain low.

About 5.5 million policies were in force as of October 2013. Estimates of takeup rates at the national level are difficult because of a lack of data (NRC, 2015), but estimates based on detailed analysis of individual properties arrive at similar results. Based on a nationwide sample, it was estimated that approximately 50 percent of one-to-four person family homes in the SFHA were insured for flood losses (Dixon et al., 2006). Similar findings were found for one-to-four person homes in New York City on the eve of Hurricane Sandy (Dixon et al., 2013). Of these homes in the SFHA, 55 percent had flood insurance (approximately three-quarters were subject to the mandatory purchase requirement). Thus, even though the proportion of residential structures covered by the program has increased greatly since its early years, roughly half of one-to-four family homes in the SFHA still

lack insurance. Takeup rates outside of the SFHA are much lower. Estimates for one-to-four family homes run in the low single digits, with research finding the takeup rate to be less than 1 percent outside the SFHA (Dixon et al., 2006).

Contributing to modest takeup rates is the issue of flood insurance retention. NFIP policies must be renewed annually. A 2012 study examined the number of years NFIP policies remain in place and found that, of the 840,000 new policies issued in 2001, 27 percent had lapsed after 1 year and 51 percent had lapsed after 2 years (Michel-Kerjan et al., 2012). To help address the takeup rate, FEMA expended considerable effort to communicate flood risk through the FloodSmart program, Write-Your-Own (WYO) agents, and community efforts. For example, a specific goal of the FloodSmart program is to increase takeup rates (FEMA, 2015a). The GAO (2010) reported that the NFIP had demonstrated a 24 percent increase in the number of policies between the launch of FloodSmart program in 2004 to the time of this present report. Although promising, NFIP policy takeup rates remain low.

The NFIP has several program objectives, one of which is to encourage the purchase of flood insurance as an alternative to reliance on federal disaster assistance. Hence, for any policy option intended to increase takeup rates, it would be useful to assess how a CBFI option might affect program objectives and whether tradeoffs are involved.

Community Involvement in Flood Insurance

Local governments are typically involved in flood mitigation activities such as designing and building structures for flood damage mitigation; enacting and enforcing floodplain management regulations; establishing and operating flood warning systems and emergency management plans; and regulating land development in upland areas to reduce the extent to which new impervious surfaces on these lands will increase flooding downstream.

When it comes to flood insurance, however, local governments have no formal role, although some of their mitigation activities may enable flood insurance policyholders to obtain reduced premiums through the CRS. As mentioned above, in 2013 the activity of flood insurance promotion was officially added to the CRS to credit communities that actively encourage residents and businesses to purchase and maintain adequate flood insurance. However, it is the policyholders, and not the governmental entity, that reap the direct benefit of a reduced premium from a better CRS score. Of course, the community reaps the indirect benefit of better protection and lower losses from floods. If a CBFI option were available to communities to formally participate in the NFIP, then it would have the direct beneficial effect of making flood hazards and flood hazard reduction important topics of debate in the community. Chapter 4 considers how CBFI might enhance community involvement.

Communication of Flood Risk at the Community Level

It is important for property owners to understand their exposure to flood risk, as well as the consequences of their failure to buy flood insurance, especially if they live in a high-risk area such as the SFHA. Informed property owners are often well positioned to make good choices in managing their exposure to floods. The same can be said for communities that can undertake measures to better manage their floodplains and mitigate flood hazards. The NFIP through its mapping, floodplain management and insurance activities has spent considerable resources to communicate flood risk. For example, the Risk MAP program, which maps flood risk on behalf of the NFIP, conducts outreach to communities in the development and distribution of flood maps, along with activities to engage communities and communicate risks. These actions are intended to support efforts to increase public awareness of flood risk and emphasize the importance of flood mapping data in contributing to appropriate risk management decisions and actions. FEMA and other federal agencies have also implemented a High Water Mark Initiative, wherein communities post signs about their historical flood events and conduct ongoing education to build awareness.

FEMA is engaged in a compreshensive effort to reform the NFIP, which was initiated before the Biggert-Waters Flood Insurance Reform Act of 2012 (BW 2012) was enacted. The first phase involved stakeholder sessions, during which federal, state, local and tribal governments, and other entities shared concerns and recommendations (FEMA, 2009). Similar sessions were held around the country in preparation of the National Mitigation Framework, which focuses on reducing risks, as well as empowering communities to take action and increase community resiliencey (FEMA, 2010a).

Perhaps the most signicant communications effort undertaken by FEMA is the FloodSmart program, mentioned previously. This NFIP-funded advertising and marketing program is directed at encouraging homeowners to buy flood insurance. The program provides information about five main topics: flooding and flood risk, the NFIP, residential flood insurance, commercial flood insurance, and preparation and recovery (NRC, 2013). Through internet sites, television advertising, brochures, and other forms of marketing, the program disseminates information about policies, program changes, and other topics of interest to the consumer (FEMA, 2015a). The importance of communicating risk and the need for insurance suggests that periodic evaluation of communication strategies would be useful.

Flood Insurance Premium Pricing

Many pricing challenges are associated with flood insurance. Subsequently, BW 2012 called for substantial changes to how the NFIP prices

policies. More specifically, its provisions required the NFIP to move to risk-based pricing of most properties. However, when affected policyholders voiced their concerns about the implications of BW 2012, the Homeowner Flood Insurance Affordability Act of 2014 (HFIAA 2014) was enacted. HFIAA 2014 limited the premium rate increases that would have occurred for some properties if all of the BW 2012 provisions had taken effect. In particular, HFIAA 2014 delayed, but did not reverse, increases in the rates for pre-FIRM properties, but it reinstated grandfathering (NRC, 2015). The intention was to offset the revenue losses from grandfathered and CRS-discounted premiums by increasing premiums on all policies, but it is uncertain whether this objective has been achieved (NRC, 2015). HFIAA also introduced an annual premium surcharge, which will be deposited into a reserve fund.

Issues that arise from the NFIP’s approach to pricing flood insurance include, but are not limited to, financial deficits, distorted incentives with respect to flood risk management, and adverse selection. These pricing topics are discussed below.

Financial Deficits

The NFIP has incurred substantial financial debt in recent years. There are several reasons for this including, but not limited to, NFIP premium pricing practices. Since its inception, the NFIP has incurred catastrophic losses—$1 billion or more—in 7 of its 44 years. Throughout its history, the NFIP has had to borrow money from the Treasury on several occasions when its claims payments and other costs exceeded its revenues and reserves. Until 2005, the program never exceeded its cumulative debt of $1 billion, and was able to repay its loans when its claims payments were relatively low. This changed in 2005 when claim payments resulting from hurricanes Katrina, Rita, and Wilma caused huge increases in its deficits and debt. Since 2005, the NFIP’s outstanding debt has risen from $225 million to $23 billion (through December 2014). Although its revenues steadily increased during this period they have fallen far short of total claims payouts. The years 2005 ($17.8 billion) and 2012 ($8.8 billion) were especially costly with respect to claim payouts.6

There are differences between how a private insurance company prices its loss exposures and manages its finances, and how the NFIP does so. In the absence of regulatory actions, a private insurer will set prices so that, over the long term, it will generate sufficient revenues to fully cover its costs. In low-loss years it will contribute to its “surplus,” from which it can

_______________________

6 Data sourced from https://www.fema.gov/loss-dollars-paid-calendar-year [accessed on June 13, 2015].

draw funds in high-loss years. In contrast, the NFIP’s pricing structure has not generated sufficient revenues to fully fund its expected or actual losses. NFIP’s pricing incorporates other program goals that are at times at odds with the ability to cover payouts for losses, which makes the NFIP fundamentally different from private insurance (Kousky and Shabman, 2014; NRC, 2015). If the NFIP operated like a private insurer, then it would include a loading for a risk-based return on capital in its premiums. The NFIP is not pricing to build up substantial reserves (from an actuarial perspective) to cover payouts in high-loss years and/or purchase reinsurance or catastrophe bonds. BW 2012 does require the NFIP to institute assessments intended to build up loss reserves, but the GAO (2014a) has concluded that these assessments will be insufficient to achieve their intended objective.

A significant contributing factor to the NFIP’s debt seems to have been its inability to charge full-risk premiums. For example, the GAO (2014b) estimated the NFIP’s net “foregone premiums” during the period 2002-2013 to be between $11 billion and $17 billion. The GAO defined “foregone premiums” as the difference between “subsidized” premiums and “full-cost” premiums (GAO, 2014b).

BW 2012 required the NFIP to begin to build a reserve equal to 1 percent of its total potential loss exposures, but with its current pricing structure, it will not be able to meet this requirement (GAO, 2014a). In 2014, the NFIP added a 5 percent assessment on policies to build this reserve fund. However, it has been estimated that a 25 percent assessment would be needed (GAO, 2014b). The GAO (2014a) concluded that it is not possible for the NFIP to meet its reserve target under the limitations imposed by HFIAA 2014. There also is an issue as to whether the NFIP should be required to use its current rate structure and future revenues to pay off its outstanding debt to the Treasury given the statutory limits on its rate structure. The program was never intended to be actuarially sound; rather, it was assumed that FEMA would have to borrow from the federal Treasury.

Distorted Incentives

The manner in which insurance coverage is priced can have substantial effects on insurance policyholders’ incentives to manage their risk. Providing insurance, in and of itself, can lead to moral hazard by diminishing insureds’ incentives to prevent or avoid losses. Measures can be taken in the design, underwriting and pricing of insurance policies to mitigate moral hazard. Risk-based pricing is one of these measures. The more that someone pays for insurance that is tied to the risk of loss, the more he or she will be induced to take steps to reduce the risk of loss or cancel the policy.

Individuals and households can control or influence their exposure to flood risk primarily through their decisions about the location of the homes

they own (or rent) and measures they can take to make their homes more flood-resistant. In terms of location, individuals and households can choose to build, buy, or rent homes in areas that have a high, moderate, or low propensity for floods. A home and its contents can be made more flood-resistant through measures such as increased elevation, dry floodproofing and wet floodproofing, among others. Similar observations apply to nonresidential properties. Communities can also take steps to reduce the flood exposure of properties within their boundaries through floodplain management and hazard mitigation.

If property owners, which have a subsidized flood insurance policy, pay less than what they would pay if there policy was not subsidized, there is less incentive to mitigate against flood loss. As discussed above, there are three primary groups of polices or properties that are currently charged less than what FEMA considers to be full-risk premiums—pre-FIRM subsidized policies, grandfathered policies, and policies that receive CRS discounts. Further, there are 6 categories of subsidized policies provided by NFIP. Some examples of these are pre-FIRM policies, policies on properties newly mapped into the SFHA, and policies within different flood zones.

The subsidies provided to the owners of pre-FIRM subsidized properties likely will not affect decisions on where to build new homes, because they apply to existing properties only. They will, however, affect the decisions of prospective buyers of these properties, because HFIAA 2014 allows new owners of these properties to maintain coverage at the historical rate. Through time, the pre-FIRM subsidized rates will gradually increase, although at a slower pace than what the BW 2012 had mandated.

The premium reductions received by the owners of pre-FIRM subsidized, grandfathered, and discounted CRS properties would also be expected to reduce their incentives to undertake measures to make their properties less vulnerable to flood damage.

If a property owner is paying an artificially low premium, then he or she may perceive that any reduction in their premium to be small relative to the cost of undertaking a mitigation measure such as floodproofing. That said, as the rates for pre-FIRM properties gradually increase, the perceived benefits of floodproofing investments should also increase relative to their costs. The time horizon that a property owner would use in any cost-benefit analysis would be important, because the net present value of the anticipated premium savings over an extended period could be substantial.

Discounts and subsidies received by NFIP policyholders would also be expected to diminish the incentives for communities to manage their floodplains and invest in hazard mitigation. If the owners (or renters) of these properties paid risk-based rates, then they would be more motivated to request officials in their communities to undertake measures to reduce their flood exposure to lower their premiums.

Adverse Selection

If an insurer is unable to charge premiums commensurate with individuals’ risk of loss, then it will be exposed to the problem of adverse selection (Box 3-1). Arguably, the NFIP is purposely structured to encourage adverse selection at the high end of the risk spectrum, because one of the NFIP objectives is to motivate owners of high-risk properties to buy flood insurance, even if the premiums paid are less than what it costs to insure. If owners of moderate or low-risk properties perceive (rightly or wrongly) that the premiums they would pay are “too high” relative to their risk of loss, then they will be less inclined to buy flood insurance. This is a problem for two reasons: (1) given that owners of moderate- and low-risk properties still have some flood exposure if they choose not to buy flood insurance, then they risk incurring uninsured flood losses; and (2) if the NFIP pricing structure discourages the owners and renters of moderate- and low-risk properties from buying flood insurance, then the program’s ability to achieve a broader pool of risk exposures, which is generally considered to be desirable for other types of insurance, is compromised. Two concepts are pertinent here: (1) increasing the size of an insurance pool can reduce objective based risk, which could be viewed as an economy of scale. However, insurance experts posit that the efficiencies gained through pooling larger numbers of loss exposures does not require that the exposures be of “similar risk” (Harrington and Niehaus, 2004; Rejda and McNamara, 2014); and (2) it would be impractical to establish a pool of insureds with similar

BOX 3-1

Adverse Selection

“Adverse selection is the tendency of persons with a higher-than-average chance of loss to seek insurance at standard (average) rates, which if not controlled by underwriting, results in higher-than-expected loss levels” (Rejda and McNamara, 2014). Adverse selection can occur because of asymmetric information (individuals know more about their risk level than insurers) or government restrictions on insurers’ ability to charge risk-based prices, or a combination of both. The extent to which adverse selection becomes a problem can depend upon the severity of the asymmetric information problem, the extent to which people change their insurance purchasing decision as premiums change, and any restrictions on insurers’ ability to employ risk-based underwriting and pricing. Also, the degree to which the purchase of insurance is voluntary or compulsory will affect adverse selection. If the purchase of insurance is voluntary, then insurers will be subject to greater adverse selection.

risk levels: insurers generally seek to achieve “a balance” within their pools of insureds so that they are not overly weighted with high-risk insureds.

The extent to which low takeup rate for owners of moderate- and low-risk properties can be attributed to adverse selection is a matter for speculation. In addition, if the owners of some high-risk properties are charged a premium higher than what it costs to insure them, then less-than-satisfactory takeup rates in high-risk areas could result. Given current limitations on the mandatory purchase requirement and the problems that have been encountered in its enforcement, this issue may warrant further investigation. The NFIP’s gradual movement to risk-based rates for pre-FIRM structures would be expected to make the program less subject to adverse selection. The assessments and surcharges being imposed on all insureds would be expected to have the opposite effect. These are issues that warrant consideration as further modifications to the NFIP, such as CBFI are explored. However, there are many pricing challenges associated with flood insurance and they are neither created by nor avoided by the use of CBFI.

Socioeconomic Factors

Modest takeup rates for individual property flood insurance exist within NFIP-participating communities in SFHAs. These rates are less than modest in NFIP-participating communities outside of the SFHAs. These modest to less than modest takeup rates can potentially be explained by property owners deliberatively evaluating premiums and deductibles for various flood insurance policies against the probability and severity of flood losses (NRC, 2015), and rationally choosing to purchase little or no flood insurance within this cost/benefit, decision-making context. However, the purchase of flood insurance may not be based solely on rational, financial, cost/benefit considerations, but may be subject to nonfinancial considerations and intuitive (rather than deliberative) thinking (NRC, 2015).

Intuitive thinking is predicated upon emotionally driven responses and mental shortcuts that are often conditioned by personal past experience, social context, and cultural factors (Kunreuther et al., 2014). This type of thinking does not necessarily work well when making decisions around low-probability, high-consequence events such as flooding (Kunreuther et al., 2014), because it is subject to several deliberative biases. For example, homeowners will often purchase flood insurance immediately after a salient flood event they now considered to be most likely (availability bias), but will allow this policy to lapse after a few years if no further flood event occurs (NRC, 2015). Other responses and mental shortcuts include budgeting heuristics, biases in temporal planning (e.g., hyperbolic discounting), learning failures and status quo bias (reluctance to consider new alternatives), risk framing, and social norms and interdependencies (see Kunreuther et al.,

2014, and NRC, 2015 for a more detailed discussion). These nonfinancial and intuitive thinking considerations should be accounted for when designing policy options aimed at increasing flood insurance takeup rates.

To encourage participation in the NFIP, both pre-FIRM subsidized policies and grandfathered policies were instituted to avoid penalizing property owners (and corresponding local communities) who might otherwise see a significant decrease in property values. Furthermore, these policy premiums were neither means tested, nor targeted at lower-income property owners (Kunreuther and Michel-Kerjan, 2013a). It is estimated that 20 percent of the 5.5 million policyholders (34 percent of all policies in the SFHA) pay about 40-45 percent of the true full-risk premium (Hayes and Neal, 2011; GAO, 2013). These values apply to pre-FIRM subsidized policyholders.

Thus, movement toward premiums that reflect full risk for all property owners in a community—ostensibly what would occur under a CBFI option that removes premium subsidies—would ideally account for the premium increases potentially imposed, especially on lower income property owners for whom this would be an financial burden. That is, full-risk premiums for all property owners should address issues of affordability of insurance. A 2015 report provides a detailed example of the magnitude of rate increases for a subset of existing pre-FIRM SFHA policyholders in Charleston, South Carolina moving toward post-FIRM, full-risk premiums based upon the current NFIP rating manual (Zhao et al., 2015).

The broader flood insurance affordability impact will also likely be experienced in the near term because of current issues of modest to low insurance takeup rates and poor enforcement/compliance. These low market penetration issues are further compounded by expectations of disaster relief, whereby property owners in high flood risk areas have not taken steps to reduce their exposure or have adequate insurance in place because they assume they will be compensated if a disaster occurs (Kunreuther and Michel-Kerjan, 2013a). In fact, actual disaster assistance is likely to be much smaller and more uncertain than is commonly perceived. Increasing flood insurance market penetration is unlikely to reduce disaster assistance (Dixon et al., 2006). All told, low takeup rates, poor enforcement/compliance, and disaster relief expectations are believed to have led to continued development in high-risk flood areas without the corresponding purchase of flood insurance.

Equity and economic stability are prominent socioeconomic considerations for a community. Full-risk premiums may impose a significant financial burden on lower-income households, and a number of high-income policyholders have benefitted from NFIP-discounted policies. For example, wealthy property owners with waterfront homes that are not their primary residence have purchased insurance from the NFIP at subsidized rates; however, subsidies are now being phased out on these properties at a rate of

25 percent per year. Although movement toward full-risk premiums would impact these policyholders, the financial burden would not be significant; more importantly, it would add to the community’s overall flood insurance portfolio, potentially unequally shared amongst wealthy and non-wealthy property owners through cross-subsidized insurance premiums. As mentioned above, premium discounts were also provided to avoid negative impacts on property values. Thus, movement toward full-risk premiums in a community could have significant real estate and consequently local tax base implications. Decreased property values could impact a community today, as well as into the future, because lower tax revenues would force public spending trade-offs. Again, it is doubtful that these negative impacts would be felt equally across all NFIP participants.

A large body of literature demonstrates that socially vulnerable populations—particularly low-income and minorities—experience greater impacts from storms and flooding (Van Zandt et al, 2012), in part because they are unable or unwilling to adequately insure their property, and in part because they are at greater risk of exposure. Within communities, people and households are not distributed randomly—the risk of exposure is not borne equally. In many communities, low-income households are located in low-lying areas, often in low-quality buildings. These situations result from market forces and intentional development decisions that place lower-income households (including rental housing) in less desirable/more hazardous areas. As a consequence, low-income households may have limited housing choices. Part of the appeal of CBFI is the potential to spread risk throughout the community (Keybridge Research, 2011), which may encourage the protection of vulnerable areas.

Finally, community socioeconomic factors are not limited to impacts on private property owners within a community. Two important considerations in this regard are public infrastructure and the environment. With regard to the former, as part of the 1988 Stafford Act, after the declaration of a Presidential disaster the federal government is authorized to provide at least 75 percent of the funds, that is, disaster assistance/relief, required to restore damage to infrastructure and public buildings (Kunreuther and Michel-Kerjan, 2013b), most of which are uninsured and/or unmitigated toward disaster impacts. FEMA has responsibility for coordinating this disaster relief.

Disaster assistance has not been limited to FEMA allocations. It has been distributed through numerous other federal agencies (Staff, Subcommittee on Economic Development, Public Buildings, and Emergency Management, 2015). For example, $60 billion in total disaster relief has been appropriated due to Hurricane Sandy with the largest allocation ($15.2 billion) going to the Department of Housing and Urban Development Community Development Funds. Other large disaster relief appropriations

went to the Department of Transportation Federal Transit Administration Emergency Relief Program and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Staff, Subcommittee on Economic Development, Public Buildings, and Emergency Management, 2015). This $60 billion to provide disaster relief primarily to infrastructure and public buildings dwarfs the $7.8 billion in NFIP claims paid.7 In light of this, calls have been made for communities in hazard prone areas to pay insurance with full-risk premiums to cover damage to public infrastructure and buildings (Kunreuther and Michel-Kerjan, 2013b), and these issues merit consideration in a CBFI option.

Within the NFIP, flood insurance is primarily offered to individuals. Although there is no present CBFI option, communities can participate in the NFIP in several ways. Communities play a substantial role in flood risk management, often receiving federal resources to engage in such activities. This chapter highlights some of these programs to illustrate the precedent for community-based approaches. For example, the CRS is an incentive based voluntary program for NFIP communities to reduce flood risk. The CRS uses a class rating system and for each improvement in class, a discount is offered on flood insurance to individual policyholders. Other examples of community participation in the NFIP include flood risk and floodplain management, the Cooperating Technical Partners Program and Risk Map, and the Flood Mitigation Assistance Program. These experiences merit further review if a CBFI option is pursued.

This chapter discussed the following key flood insurance topics:

- Participating Communities. The NFIP impacts participating communities in different ways. Some communities have a large number of policies-in-force, while other communities have very few policies-in-force. Therefore, there is little evidence to define an average NFIP community, suggesting that a one-size-fits-all approach to a CBFI option may be difficult to develop.

- Takeup Rates. Takeup and retention rates for flood insurance are often low. Mandatory purchase requirements, which might raise both rates, are likely to encounter political resistance.

- Community Involvement in Flood Insurance. Municipal governments do not write NFIP policies. They are, however, involved in floodplain management and mitigation activities that may impact flood insurance premiums.

_______________________

7 Significant flood events. Available at https://www.fema.gov/significant-flood-events [accessed on July 8, 2015].

- Communication of Flood Risk. Informed property owners are often well positioned to manage flood risk, which includes the flood insurance purchase decision. FEMA has spent considerable effort, with measurable success, in communicating flood risk at the individual and community levels.

- Flood Insurance Pricing. Pricing within the NFIP differs from pricing in the private sector. If discounted or subsidized policyholders had to pay risk-based rates, then policyholders may be more motivated to engage community officials to undertake measures to reduce flood exposure, thereby reducing flood insurance premiums.

- Socioeconomic Factors. Because increasing takeup rates is a goal, nonfinancial and intuitive thinking merit consideration. Movement toward full-risk premiums in a community could significantly affect real estate values and the local tax base. Socioeconomic factors are not limited to private property owners within a community; other important considerations include public infrastructure and the environment.

BOX 3-1

Adverse Selection

“Adverse selection is the tendency of persons with a higher-than-average chance of loss to seek insurance at standard (average) rates, which if not controlled by underwriting, results in higher-than-expected loss levels” (Rejda and McNamara, 2014). Adverse selection can occur because of asymmetric information (individuals know more about their risk level than insurers) or government restrictions on insurers’ ability to charge risk-based prices, or a combination of both. The extent to which adverse selection becomes a problem can depend upon the severity of the asymmetric information problem, the extent to which people change their insurance purchasing decision as premiums change, and any restrictions on insurers’ ability to employ risk-based underwriting and pricing. Also, the degree to which the purchase of insurance is voluntary or compulsory will affect adverse selection. If the purchase of insurance is voluntary, then insurers will be subject to greater adverse selection.