![]()

Federal Role in the Inland Waterways System

The inland waterways infrastructure is managed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) and funded from the USACE budget. The first section below describes USACE missions and activities, a major component of which is providing for commercially navigable inland waterways. The next section gives an overview of the authorization, planning, and budgeting process for the inland waterways system and how spending is prioritized. Recent trends in funding levels for the inland waterways system and who pays for the system according to the cost-sharing rules specified in current federal legislation are discussed. The greater involvement of the federal government in the inland waterways relative to other modes is described. Considerations with regard to the federal role in funding the inland waterways are explained, including reasons and mechanisms for assessing payments from those who benefit from the system. The final section summarizes findings and conclusions from the chapter.

With the authorization of Congress, USACE, under its Civil Works Program headed by the Assistant Secretary for Civil Works, plans, constructs, operates, and maintains a large water resources infrastructure that includes locks and dams for inland navigation; maintenance of harbor channel depths; dams, levees, and coastal barriers for flood risk management; hydropower generation facilities; and recreation. The primary USACE Civil Works mission areas are support of navigation for freight transportation and public safety; reduction of flood and storm damage; and protection and restoration of aquatic ecosystems,

such as the rebuilding of wetlands and the performance of environmental mitigation for USACE facilities. Hydropower generation is an important activity of USACE, although it has not been considered a primary mission. Other USACE responsibilities include recreation, maintenance of water supply infrastructure (municipal water and wastewater facilitates), and disaster relief and remediation beyond flood disaster relief (e.g., remediation of formerly used nuclear sites). Some infrastructure projects are authorized as multiple-use projects for navigation and other purposes (e.g., hydropower, municipal water supply, recreation), with the costs being allocated among the various users, but most projects are authorized for a single purpose. Navigation projects are authorized, and the federal share of costs paid, with funds from the USACE navigation budget. Hence, with the exception of a few multipurpose projects, USACE’s navigation mission, its costs, and its benefits are separable from USACE’s other missions.

Overview of the USACE Water Resources Authorization, Planning, and Budgeting Process

CAPITAL PROJECTS: NEW CONSTRUCTION AND MAJOR REHABILITATION

The inland waterways system is both part of a larger national freight transportation system and part of the nation’s watershed system (system of rivers and canals). This dual role complicates decisions about management and funding of the inland waterways. Whereas some federal agencies have broad authorities, Congress authorizes each capital investment for capacity expansion, facility replacement, or major rehabilitation of USACE water infrastructure projects. A construction project generally originates with a request to a congressional office from communities, businesses or other organizations, and state and local governments for federal assistance.1 Since 1974, the process for authorizing federal water resources projects, including infrastructure for freight transportation, has been the omnibus bill typically

________________

1 At this early stage, USACE typically engages in an advisory role to answer technical questions or to assess the level of interest in possible projects and the support of nonfederal entities (state, tribal, county, or local agencies and governments) that may become sponsors.

called the Water Resources Development Act (WRDA).2 On the basis of this legislation, Congress authorizes individual capital projects and numerous other USACE activities and provides policy direction in areas such as project delivery, revenue generation, and cost-sharing requirements. Benefit–cost analysis is the primary criterion used in selecting capital expenditures projects for funding. Projects that pass a minimum threshold for determining that the benefit exceeds the cost are eligible for congressional authorization and funding.

Two types of congressional authorizations are required for a construction project—one for investigation and one for project implementation.3 First, authority is provided for a feasibility study in which the local USACE district investigates engineering feasibility, formulates alternative plans, conducts benefit–cost analysis, and assesses environmental impacts under the National Environmental Policy Act.4 The study results are conveyed to Congress through a Chief of Engineers Report (Chief’s Report) that contains either a favorable or an unfavorable recommendation for each project. Study results also are submitted to the executive office of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), which applies its own fiscal, benefit–cost, and other criteria to assess whether projects warrant funding according to executive branch objectives. Congress considers USACE study results, recommendations of OMB, and other factors in choosing projects to authorize. Thus, both the projects selected for initial study and the project authorizations are at the discretion of Congress.5

After Congress authorizes a project, it becomes eligible to receive implementation funding in annual Energy and Water Development appropriations acts. The appropriations process begins with the submission of the annual President’s budget. To be included in the President’s budget, authorized projects must compete within the overall

________________

2 The 2014 authorizing legislation is titled the Water Resources Reform and Development Act (WRRDA).

3 If the geographic area was investigated in previous studies, the study may be authorized by a resolution of either the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee or the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee.

4 According to WRRDA 2014, at any point during a feasibility study, the Secretary of the Army may terminate the study when it is clear that a project in the public interest is not possible for technical, legal, or financial reasons.

5 After a project is authorized, modifications beyond a certain cost and scope require additional congressional authorization.

USACE program ceiling not only for initial funding but also for continued annual funding throughout the project’s life cycle. Once Congress receives the President’s budget request, it is “marked up” by the House and Senate Appropriations Committees, where project funding levels are adjusted in response to congressional priorities. Even if an authorized project has received initial construction funding, there is no assurance that it will receive sufficient appropriations each year to provide for an efficient construction schedule. The actual funding for the project over its life cycle may be much less suitable.

A previous National Research Council (NRC) report (2012) encouraged less reliance on WRDA as the main vehicle for authorizing projects for USACE infrastructure. The traditional focus on WRDA for authorizing large new construction projects in particular is less relevant to a system that is mostly “built out” and for which the main concern is a sustainable source of funding for ongoing operations and maintenance (O&M) and major repairs.

Although WRDA drives capital funding for freight transportation on the inland waterways, it is largely disconnected from federal legislative processes and efforts related to other freight modes. Similarly, the goal of the USACE planning process is to determine whether a navigation project is eligible for funding, not to assess whether the project will be the most efficient option for meeting national freight transportation needs and economic interests given the availability of other modes. (The benefit–cost analyses required for the authorization of navigation projects must consider other modes to a degree, as described later in this chapter.) The inland waterways system is not unique in this regard; a national freight system perspective on the efficiency of the nation’s freight network is generally lacking, and no mechanism exists for prioritizing spending across modes.

OPERATIONS AND MAINTENANCE

O&M projects can be authorized under WRDA, but it has not often been used for this purpose (see NRC 2012, Table 2-2, for exceptions in WRDA 2007). USACE headquarters sets priorities for O&M

investments as part of the budgeting process on the basis of information gathered from USACE districts and divisions. Eight USACE divisions coordinate projects and budgets in 38 district offices across the United States. Districts develop plans, priorities, and rankings for investigations, construction, and O&M and submit them to USACE divisions. Divisions prioritize projects across their districts and provide divisionwide rankings of projects to USACE headquarters. USACE headquarters considers division priorities and rankings, administration budget priorities, and other factors in ranking requests.6 The number of projects funded each year depends on the annual budget appropriation by Congress.

The local assessment of assets and maintenance needs follows general guidelines, but it has many local variations. For example, districts may develop their own asset management systems for assessing and communicating the condition of infrastructure and level of service being provided for navigation and O&M and repair needs. According to a past NRC report, with respect to water resources funding, “neither the Congress nor the administration provides clear guiding principles and concepts that the USACE might use in prioritizing OMR [operations, maintenance, and repair] needs and investments” (NRC 2012, 11). Full benefit–cost analysis is applied only to construction and not to O&M,7 which is appropriate given the costs of conducting benefit–cost analysis relative to the cost of O&M projects. USACE is developing an approach to asset management that could be applied systemwide to improve identification and prioritization of maintenance and repair needs and spending (see Chapter 4).

DISTINCTIONS AMONG O&M, MAJOR REHABILITATION, AND CONSTRUCTION

USACE separates projects labeled as “major rehabilitation” from its O&M budget. Major rehabilitation projects meet the following criteria

________________

6 The USACE budget submitted as part of the President’s budget request is not commensurate with all local requests given the lack of available funds and competing priorities within and across USACE programs (e.g., hydropower, recreation).

7 As discussed in the next section and Chapter 4, rehabilitation projects of more than $20 million are classified arbitrarily as a capital cost.

established in a series of Water Resources Development Acts from 1986 to 2014.8

- Requires approval by the Secretary of the Army and construction is funded out of the Construction General Civil Works appropriation for USACE.

- Includes economically justified structural work for restoration of a major project feature that extends the life of the feature significantly or enhances operational efficiency.

- Requires a minimum of 2 fiscal years to complete.

- Costs more than $20 million in capital outlays for reliability improvement projects or more than $2 million in capital outlays for efficiency improvement projects. These thresholds are adjusted annually by regulation and are subject to negotiation.

Major rehabilitation projects are treated as capital projects for new construction in the budgeting process instead of being considered an expense of maintaining the system. The decision to classify major rehabilitations as a capital expenditure instead of as an O&M expense is arbitrary.9

Funding for the Inland Waterways Navigation System

COST-SHARING RULES

Before 1978, the inland navigation system was funded almost entirely through general revenues collected from taxpayers. Congress transformed funding for the inland waterways by passing two pieces of legislation: the Inland Waterways Revenue Act of 1978 and the Water Resources Development Act of 1986, which created the funding framework followed today. This legislation established a tax on diesel fuel for commercial vessels paid by the barge industry and an Inland

________________

8 The $8 million ceiling for O&M was set in WRDA 1986 (P.L. 99-662). WRDA 1992 (P.L. 102-580) established a statutory definition for “rehabilitation” of inland waterways projects. WRRDA 2014 (P.L. 113-121) increased the ceiling from $8 million to $20 million for rehabilitation projects that can still be considered O&M. (With the escalation that accompanied the $8 million ceiling set in WRDA 1986, the ceiling for federal spending on rehabilitation projects was already at $16.5 million by 2014.)

9 The Federal Highway Administration, for example, more clearly distinguishes between projects for maintenance and capital projects that significantly alter the function or expand the physical capacity of an asset.

Waterways Trust Fund (IWTF) to pay for construction with fuel tax revenues. It also increased the nonfederal cost-sharing requirements for inland navigation construction projects.10

The required cost share depends on whether the navigation project is classified as a capital cost or as O&M. For single-purpose navigation projects and multiple-purpose projects assigned to the navigation budget, the federal government pays 100 percent of O&M costs, 50 percent of capital costs (including capacity expansion, replacement, and major rehabilitation), and 100 percent of rehabilitation costs up to $20 million (costs for a single repair or set of repairs that exceed this amount are considered major rehabilitation and a capital cost). The waiving or adjustment of cost-sharing requirements for individual projects is infrequent and typically requires authorization by Congress.

The federal share for commercial navigation is paid via general revenues. The commercial users’ share is paid for with a diesel fuel tax per gallon via the IWTF; the tax is collected by the Internal Revenue Service. The fuel tax was initially set at $0.04 per gallon and is not indexed to inflation. In 1986 legislation, the tax was set to rise to its current level of $0.20 per gallon, where it has remained until 2014, when the 113th Congress approved an increase in the barge fuel tax to $0.29 per gallon.

In contrast to the cost share for navigation, the O&M costs for nonnavigation projects are paid for partly by sponsors. The federal share depends on the type of water resource project (see Table 3-1). For many project types (e.g., levees), the nonfederal sponsor is responsible for O&M once construction is complete. Furthermore, inland waterways feasibility studies to determine the eligibility of a navigation project

________________

10 The IWTF does not apply to ports and harbors. A separate Harbor Maintenance Trust Fund (HMTF) was established in 1986. The HMTF is designated only for O&M of federally authorized channels for commercial navigation in deep draft harbors and shallow draft waterways that are not subject to the IWTF fuel tax (Frittelli 2013). The HMTF is based on a 0.125 percent ad valorem tax imposed on imports, domestic shipments, and cruise line passenger tickets at designated ports (collected by U.S. Customs). Major port construction traditionally has been financed with existing reserves, cash from operations, government grants, and loans. Often port districts are set up to operate the port and borrow from capital markets, with bonds being paid off via user fees or property taxes. More recently, ports have begun examining joint venture financing, in which their customers assume most of the debt associated with a capital project, and third-party financing, in which an entity invests in project design and construction but may not operate the facility (see http://www.aapa-ports.org).

TABLE 3-1 Standard Construction and O&M Cost-Sharing Requirement for USACE Projects

| Project Purpose | Maximum Federal Share of Construction (%) | Maximum Federal Share of O&M (%) |

| Navigation | ||

| Coastal ports— | ||

| <20-ft harbor | 80a | 100b |

| 20- to 50-ft harbor | 65a | 100b |

| >50-ft harbor | 40a | 50b |

| Inland waterways | 100c | 100 |

| Flood and hurricane damage reduction | ||

| Inland flood control | 65 | 0 |

| Coastal hurricane and storm damage reduction except periodic beach renourishment | 65 | 0 |

| Repair of damaged flood and coastal storm projects | 50 | 0 |

| Locally constructed flood projects | NA | 80d |

| Federally constructed flood and coastal projects | NA | 100d |

| Aquatic ecosystem restoration | 65 | 0 |

| Multipurpose project components | ||

| Hydroelectric power | 0e | 0 |

| Municipal and industrial water supply storage | 0 | 0 |

| Agricultural water supply storage | 65f | 0 |

| Recreation at Corps facilities | 50 | 0 |

| Aquatic invasive species control and prevention | NA | 30 |

| Environmental infrastructure (typically municipal water and wastewater infrastructure) | 75g | 0 |

NOTE: Information comes from 33 USC §§2211–2215 unless otherwise specified in footnotes a through g.

NA = not applicable.

a These percentages reflect that the nonfederal sponsors pay 10, 25, or 30 percent during construction and an additional 10 percent over a period not to exceed 30 years.

b Appropriations from the HMTF, which is funded by collections on commercial cargo imports at federally maintained ports, are used for 100 percent of these costs.

c Appropriations from the IWTF, which is funded by a fuel tax on vessels engaged in commercial transport on designated waterways, are used for 50 percent of these costs.

d 33 USC §701n. Repair assistance is restricted to projects eligible for and participating in the USACE Rehabilitation and Inspection Program and to fixing damage caused by natural events.

e Capital costs initially are federally funded and are repaid by fees collected from power customers.

f For the 17 western states where reclamation law applies, irrigation costs initially are funded by USACE but repaid by nonfederal water users.

g Most environmental infrastructure projects are authorized with a 75 percent federal cost share; a few have a 65 percent cost share.

SOURCE: Carter and Stern 2014.

for funding are entirely a federal expense; in contrast, for deepwater navigation and nonnavigation projects, the federal share for feasibility studies is 50 percent.11

ROLE OF THE INLAND WATERWAYS USERS BOARD

WRDA 1986 established a federal advisory committee subject to the Federal Advisory Committees Act, the Inland Waterways Users Board (IWUB), which represents shipping industry interests. IWUB was created to give commercial users the opportunity to inform priorities for projects funded from the IWTF. WRDA 1986 specifies that the board consist of 11 members representing shipping interests in the primary geographical areas served by inland waterways, with consideration given to tonnage shipped on the respective waterways. IWUB makes recommendations to the Secretary of the Army and Congress with regard to IWTF investments. The board is advisory only. Congress and the administration choose whether to follow the board’s guidance.

WRRDA 2014 stipulates greater involvement of IWUB in project development and oversight than in previous years. According to the 2014 WRRDA, IWUB is to provide advice and recommendations to the Secretary of the Army and to Congress concerning construction and rehabilitation priorities and spending levels; feasibility reports for projects on the inland waterways system; increases in the authorized cost of project features and components; and development of a long-term, 20-year capital investment program. A representative of IWUB, appointed by the board’s chair, is to serve as an adviser to project development teams for qualifying projects and for studies or designs of commercial navigation features and components for waterways and harbors. The President’s 2015 budget request included $860,000 to support IWUB activity. The Secretary is to communicate with IWUB at least quarterly on the status of commercial navigation

________________

11 Before WRRDA 2014, a reconnaissance study to assess the need and support for a project was produced at 100 percent federal expense for navigation projects. WRRDA 2014 replaced the reconnaissance study with a preliminary study that is combined with the feasibility study as the first phase of analysis. According to the Congressional Research Service (Carter and Stern 2014), post-WRRDA 2014 cost sharing of the preliminary analysis portion of the first phase has not been clarified. WRRDA 2014 established a maximum federal cost of $3 million for most feasibility studies.

studies, designs, and construction. The board provides guidance relating only to capital investments, since current law specifies that fuel tax revenues from the shipping industry are to be used for capital expenditures and not for O&M.

PATTERNS AND TRENDS IN FUNDING FOR THE INLAND WATERWAYS SYSTEM

The FY 2015 federal budget appropriated more than $1.8 billion for USACE navigation projects,12 with about $834 million of this amount provided for inland waterways navigation.13 In recent years, the demand for O&M for the inland waterways has increased with the aging of infrastructure. As shown in Table 3-2, O&M has become a larger share of the administration’s inland navigation budget request. It now accounts for about three-fourths of the requested budget (Table 3-2).14

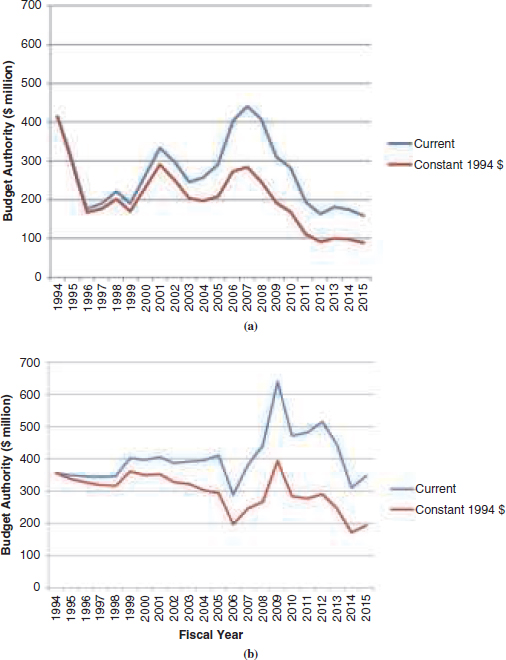

In terms of constant dollars, funding for construction and O&M for lock and dam facilities is at its lowest point in more than 20 years and is on a downward trajectory (see Figures 3-1a and 3-1b).

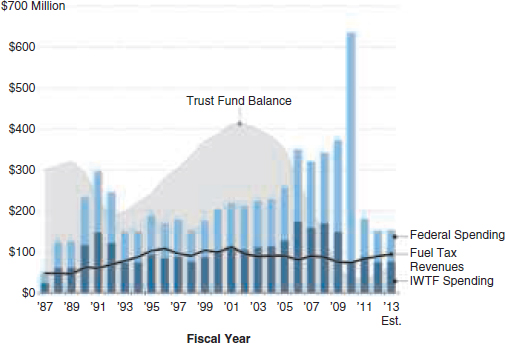

The balance of the IWTF, which is used to pay 50 percent of construction costs, has declined. The fund was at its highest level, $413 million, in 2002 (see Figure 3-2). The balance fell sharply between 2005 and 2010 as expenditures for inland waterways exceeded fuel tax collections and interest on the trust fund balance. Reasons for the decline include increased appropriations, lower fuel tax revenues than in previous years, large construction costs, and construction cost overruns.

Capital projects are funded incrementally by Congress through the annual budgeting and appropriations process. Incremental federal funding, an increasingly common procedure in which only a portion of the total budget for a project is appropriated, contributes to

________________

12http://www.usace.army.mil/Portals/2/docs/civilworks/budget/strongpt/fy15sp_navigation.pdf.

13 In the past decade, USACE Civil Works appropriations (which include both general revenues and sponsor support) have ranged from $4.5 billion to $5.5 billion to support the USACE primary mission areas (navigation, flood control and prevention, ecosystem restoration) and the other services that USACE has authorities to provide (water supply; hydroelectric power; water-based recreation; and design depths for the nation’s ports, harbors, and associated channels).

14 Although the administration budget requests will differ from federal appropriations, this table shows requested amounts because the level of budget detail for the inland waterways needed for this report (e.g., for inland navigation O&M) is not publicly available for federal appropriations. However, federal appropriations for O&M and construction for locks and dams are available, as shown in Figures 3-1a and 3-1b.

TABLE 3-2 Administration Budgets for USACE Inland Navigation, FY 2008–FY 2015

| President’s Budget (FY) | Investigations | Construction | Regular O&M | MR&T O&M | MR&T Investigations and Construction | Total Inland Nav | O&M Budget as % of Total Inland Nav |

| 2015 | 5 | 180 | 612 | 29 | 8 | 834 | 77 |

| 2014 | 7 | 237 | 608 | 42 | 11 | 904 | 72 |

| 2013 | 8 | 201 | 529 | 28 | 14 | 780 | 71 |

| 2012 | 11 | 166 | 531 | 22 | 13 | 743 | 74 |

| 2011 | 10 | 176 | 550 | 28 | 15 | 779 | 74 |

| 2010 | 3 | 170 | 577 | 32 | 15 | 796 | 77 |

| 2009 | 3 | 307 | 586 | 25 | 10 | 931 | 66 |

| 2008 | 7 | 406 | 604 | 25 | 10 | 1,052 | 60 |

NOTE: Except for percentages, figures are dollar amounts in millions. MR&T = Mississippi River and Tributaries flood control project, which was authorized through the Flood Control Act of 1928. Nav = navigation.

SOURCE: USACE headquarters.

FIGURE 3-1 USACE budget authority, FY 1994–FY 2015, for (a) lock and dam construction and (b) lock and dam O&M. FY 2014 and FY 2015 data for both construction and O&M are estimates from the President’s FY 2015 budget for the Civil Works Program, USACE. Figure 3-1a includes appropriations from the IWTF for construction not included in Figure 3-1b since the IWTF is not to be used for O&M.

SOURCE: Adapted from Kruse et al. 2012.

FIGURE 3-2 Inland waterways financing trends. Amounts are in nominal dollars and represent funding for construction only. Federal spending for FY 2009 and FY 2010 reflects congressional stopgap measures and supplemental funding under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (P.L. 111-5). [Federal spending includes total revenues disbursed by the federal government to pay for commercial navigation on the fuel-taxed inland waterways system, including general revenues from taxpayers and fuel tax revenues from carriers. The IWTF (50 percent contributed by shippers and 50 percent contributed from general revenues) is dedicated to capital costs and is not used to pay for O&M.]

SOURCE: Stern 2014 (USACE data adapted by the Congressional Research Service).

project delivery delays and higher costs (NRC 2011; NRC 2012, 29, gives another example on the Lower Monongahela River). Between 2005 and 2010, Congress made a conscious effort to “spend down” the IWTF to accelerate project completions and reduce the size of the backlog of authorized projects.

CAPITAL PROJECTS BACKLOG

A substantial number of water resources projects that have been authorized by Congress via WRDA remain unfunded through the appropriations process. These projects are known as the backlog. WRRDA 2014 included provisions to reduce the backlog and prevent backlogs in the future; whether the provisions will achieve this purpose is unclear.15 Congress considers the recommendations of USACE and OMB, but the selection of waterways projects for authorization has a long history of being driven largely by political and local concerns (Ferejohn 1974). In recent years, congressionally directed spending has taken the form of providing additional funding for broad categories of ongoing activities not included in the President’s budget. USACE is responsible for selecting which of these activities to undertake and for prioritizing them on the basis of directions and exclusions provided in the WRRDA.

While concerns about the backlog have been expressed, its size is not a reliable indicator of the funding needed for the inland navigation system for at least three reasons. First, O&M spending is not reflected in the backlog. With the aging of the system, maintenance has become a higher priority. Second, navigation projects make up only a portion of the backlog ($4.1 billion) (Carter and Stern 2011); most of the backlog relates to waterways infrastructure serving other purposes such as flood control.

Third, not all of the projects in the navigation backlog are priorities. In contrast to its practice for other modes, Congress authorizes and appropriates funds on a project-by-project basis. Benefit–cost

________________

15 The bill required the Secretary of the Army to identify a list of projects totaling $18 billion that would qualify for deauthorization. However, Congress also authorized 34 new construction projects, which added nearly $16 billion to the federal backlog. The number of authorized projects is likely to grow through allowed forms of congressionally directed spending.

analysis is used to determine whether a construction projects meets a minimum threshold of eligibility for pursuing authorization and appropriations and is generally suitable for this purpose,16 but the lack of a prioritization process based on a formal assessment of system needs has resulted in the authorization of more projects than can be funded within the constraints of the budget. The current practice is for OMB to set a minimum benefit–cost ratio that projects must meet to be included in the President’s annual budget request.17 While benefit–cost analysis is used in determining whether a project meets a minimum threshold for authorization, there is no indication that projects are further ranked against each other during the authorization process (GAO 2010). Because more projects are authorized than can be funded, priorities are sorted out in the budgeting and appropriations process, in which both the executive branch and Congress participate. IWUB, as part of a capital projects business model, has proposed projects that might serve as a starting point for evaluating the urgency of needed repairs throughout the system (Inland Marine Transportation System Capital Investment Strategy Team 2010).

For these reasons, a method for prioritizing projects on the basis of the service needs of the system may be more useful than an attempt to estimate and seek funding for the entire backlog. As for O&M, a standard process is needed for prioritizing spending for capital projects for construction and major rehabilitation and to ascertain the level of funding required across the system to maintain reliable freight service. (Prioritization is discussed in Chapter 4.)

________________

16 However, USACE’s implementation of benefit–cost analysis has received numerous critiques mainly related to the use of optimistic traffic projections.

17 Although the benefit-to-cost ratio (BCR) must exceed 1.0, BCR thresholds and other criteria used by the administration vary annually. In recent years, more stringent and differentiated criteria have been used to select projects for funding. For the FY 2015 budget, a BCR of 2.5 was required for construction projects. See http://planning.usace.army.mil/toolbox/webinars/14Apr22_budgetworkplan.pdf. Furthermore, annual changes in BCR thresholds and the use of other BCR criteria have resulted in some projects qualifying for one year’s budget request but not qualifying in subsequent years. For example, instead of using a traditional BCR metric for the FY 2007 budget request for incomplete projects, OMB used a remaining-benefit-to-remaining-cost metric. The rationale was that if the cost of a project has increased dramatically since it was authorized, the updated cost may have become greater than the benefits. Different BCR cutoffs have been used for projects of different types in the past. For example, the administration’s FY 2010 budget request required ongoing navigation and flood control projects generally to have a BCR greater than 2.5; new projects needed to have a BCR greater than 3.2.

A number of temporary measures have been taken in an attempt to stabilize the IWTF. Beginning in 2005, the Bush administration and Congress increased annual budget appropriations for IWTF-funded construction projects. Congress also exempted the fund temporarily from the usual cost-sharing requirements, provided additional federal general revenues (through the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, which accounted for the spike in federal spending for 2010 in Figure 3-2), and waived the IWTF cost-sharing requirements for specific projects.

Cost escalations and schedule delays have been of particular concern for one project, the Olmsted Locks and Dam on the Ohio River in Illinois. As part of WRRDA 2014, Congress altered the construction cost share for the Olmsted project, which was contributing to the depletion of the IWTF, to redress a perceived inequity to commercial users and help restore the IWTF balance. The provision for Olmsted requires the federal government to pay 85 percent of construction costs for the project (instead of the usual 50 percent). The act also specified changes in project planning and delivery, with the intent of avoiding such cost overruns in the future.

FUEL TAX REVENUES AS USER CONTRIBUTION

Federal legislation specifies the waterways subject to the collection of fuel tax revenues (Figure 3-3; see Appendix A for a more detailed description of fuel-taxed waterways). Fuel tax revenues totaled $85,754,000 in 2011, the last year for which comparable data on both fuel tax revenues and expenditures are available (Dager 2013). This amount was about 49 percent of the 2011 administration budget for construction costs. The budget for inland navigation O&M in 2011 was more than $550 million; however, fuel tax revenues are only for construction and not O&M.

The increase in the barge fuel tax passed by the 113th Congress in 2014 is consistent with the proposal of IWUB in its capital projects business model report (Inland Marine Transportation System Capital Investment Strategy Team 2010). The new rate of $0.29 per gallon is 45 percent above the current tax of $0.20 per gallon. [As with the original tax of $0.20 per gallon, the increased fuel tax would not be indexed for

FIGURE 3-3 Map of inland waterways indicating where fuel taxes apply.

SOURCE: P.L. 95-502, October 21, 1978; P.L. 99-662, November 17, 1986.

inflation and would not include a capital recovery mechanism linking future taxes to expenditures (Stern 2014). Any action on these concerns would require separate legislation and falls under the jurisdiction of the House and Senate taxation committees.] Estimated revenue from the proposed fuel tax increase is not sufficient to pay to maintain the system, and other sources of funding are required (see Chapter 5 for details). As explained, fuel tax revenues are dedicated only to capital spending and not O&M, and the federal government must match the user contribution for capital costs while paying all of the O&M costs. Federal funding for capital projects therefore competes with federal funds for O&M. As indicated in the next section, for historical reasons, the federal cost share and general revenue spending for the system as a proportion of total costs are greater for the inland waterways system than for the other freight transportation modes.

Federal Involvement Compared with Other Transportation Modes

States and private enterprise led the initial building of inland waterways infrastructure and charged for use of the waterways. Federal involvement in the inland waterways system began in the 18th century, when the scope and scale of inland waterways projects grew beyond what any private entity or state could or would take on, especially without the ability to realize a monetary return on investment. Congress made these federal investments to promote inland waterways commerce, which was central to the economic development of the United States. This history has led to a unique federal role in the inland waterways system among all the freight transportation modes.

Today, waterborne transportation is the only freight mode for which Congress authorizes and appropriates funds (for construction and O&M) on a project-by-project basis. Federal management and decision-making responsibilities for freight transportation generally are fragmented across jurisdictional lines in Congress, multiple federal agencies, and different silos of funding. Whereas USACE and the U.S. Coast Guard (part of the Department of Homeland Security) manage the marine and inland waterways systems, the U.S. Department

of Transportation has responsibilities for highway, aviation, rail, and pipeline. Various congressional committees are responsible for authorizations and appropriations for the different modes. Decisions about inland waterways investments, including ports, channels, and infrastructure, are made largely at the federal level.18 However, most decisions about highway investments are made at the state and metropolitan levels. For ports, investment decisions are made mainly by independent private entities and sometimes by state or bi-state port authorities. As private transport industries, railroads and pipelines make their own decisions about investments.

Public and private shares of funding also differ across modes. Highways, aviation, ports (harbor and channel dredging and maintenance), and the inland waterways all receive federal aid for capital costs. In addition, the inland waterways, harbors, and channels receive federal general revenues support for O&M. Rail and pipeline, with which the inland waterways system competes to some degree, are almost entirely private enterprises, with minimal federal assistance for infrastructure.19 For highways, the federal government pays a significant share for new construction, but O&M is a state and local financial responsibility.

The federal government, through general revenues, pays more for water transportation as a percentage of total O&M and construction costs compared with federal contributions to highways and rail. For the inland waterways system, federal support is used to cover a large shortfall between the fees paid by users and total system costs. In contrast, fees paid by the users of highway and rail modes cover a much greater share of the capital and O&M costs of those transportation systems. General federal tax revenues pay about 90 percent of total inland waterways system costs, including the construction, operations, and maintenance of barge navigation infrastructure

________________

18 The federal government has other important roles related to regulating and securing access to petroleum and other fuel supplies for transportation. It also sets environmental and safety standards for each mode through regulation and provides for operation of the air traffic control system and aids to navigation for ports and waterways. Highway, aviation, and rail transport both freight and passengers, which has consequences for federal involvement in passenger safety regulation for those modes.

19 Railroads did receive land grants from federal and state governments in the 19th century and assistance in building networks through exercise of eminent domain. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission can exercise eminent domain for siting natural gas transmission lines.

(TRB 2009).20 This compares with virtually no federal general revenue support for rail system users and pipeline, and historically only about 25 percent federal support for highways, which are primarily derived from user fees (Federal Highway Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation, Highway Statistics 2010).21 (See Box 3-1 for further discussion of federal subsidies across freight transportation modes.)

Decisions About Federal Funding and Beneficiary Payments for the Commercial Inland Waterways System

In a climate of constrained federal funds and with O&M becoming a greater part of the inland navigation budget, a pressing policy issue is how to pay to preserve the inland waterways system for commercial navigation. The structures (locks and dams) built and maintained for freight transportation have resulted in beneficiaries beyond commercial navigation. It is reasonable and, from an economic perspective, potentially efficiency enhancing to consider whether these beneficiaries could help pay for the system. Congress, in the 2014 WRRDA (Section 2004, Inland Waterways Revenue Studies), called for a study of whether and how the various beneficiaries of the waterways might be charged. The sections below assess the available evidence on benefits of the inland waterways used for freight transportation and the economic and practical considerations in charging for the benefits received.

AVAILABLE EVIDENCE ON BENEFICIARIES

Commercial navigation is the primary beneficiary of the inland waterways system. This is recognized by USACE in the primary criterion used in determining investments for the system. The framework and approach to benefit–cost analysis that USACE uses in helping

________________

20 This figure is based on user fee revenues that equaled 10 percent of inland waterways capital (construction and major rehabilitation) and operating expenditures (O&M) in 2006: capital expenditures, $0.5 billion; operating expenditures, $0.4 billion; user fee revenues, $0.1 billion. Commercial users are required by legislation to contribute only to capital improvement costs and are not required to pay for O&M expenditures. See TRB 2009 (99, Table 3-5).

21 In recent years, large general fund transfers have been made to the Highway Trust Fund and the Aviation Trust Fund to maintain their solvency. These transfers have resulted from a political stalemate that has affected investments in highway, air, and waterways transportation since the 1990s by preventing the raising of user taxes, which in past decades had been increased regularly as needs arose.

BOX 3-1

Federal Subsidies for the Various Freight Transportation Modes

Federal subsidies for the various freight modes are complicated and contested among advocates for the modes, in part because of disagreements about (a) direct subsidies that are funded by various public sources and (b) indirect subsidies that result from costs imposed on the public (externalities) that are not part of market transactions between shippers and carriers. No authoritative study has estimated either direct or indirect subsidies across the various freight modes, although a previous Transportation Research Board study (TRB 1996) developed and pilot-tested a methodology for estimating freight external costs.

Assessing direct subsidies is more straightforward among the modes with which water competes (rail, pipeline, and, to a much lesser degree, trucking). Freight railroads are private entities that fund the vast bulk of their operations and capital and maintenance spending from their own funds. Limited federal funds are available for grade separation projects (to separate traffic for safety and mobility), a modest federal loan guarantee program is available (principally for short lines), and state governments occasionally provide public funding for such purposes as raising bridges or tunnels for double-stack trains or to improve rail access to state ports. Although public funding is minimal in proportion to the $20 billion to $25 billion railroads have invested in capital stock annually since 2007,a railroad modal competitors point out that many railroad rights-of-way were initially given in the 19th century by the federal government and states to encourage railroad development. Because pipelines are entirely private, the evaluation of subsidies is easier than for rail. Although long-distance truck–barge competition is unlikely because of the much higher cost of truck movements per ton-mile, there may be short segments in which truck and barge would compete. The trucking assessment of competitive subsidies is most complex because trucks use highways that are shared with passengers. Although both freight and passenger operators pay fuel taxes and other user

________________

a Association of American Railroads. Freight Railroad Expenditure on Infrastructure and Equipment. https://www.aar.org/Pages/Private-Rail-Investments-Power-America%27s-Economy.aspx. Accessed May 21, 2015.

fees, there is continued debate about whether the largest and heaviest trucks pay their share of the costs of building and maintaining highways (GAO 2012). Moreover, after decades of relying almost exclusively on federal and state user fees to fund interstate and intercity highways, in the past decade Congress has used general funds to supplement user fee revenues to the Highway Trust Fund (HTF) for the federal share of highway capital spending (CBO 2014). (Improved fuel economy and political opposition to raising fuel taxes have resulted in insufficient user fees into the HTF to pay for the federal share of highway capital improvements.) These general fund subsidies to highway users, of course, apply to both trucks and passengers, and, as noted, truck–barge competition is fairly limited.

Indirect subsidies lack definitive estimates in the form of external costs imposed on the public, but GAO (2011) provides a high-level comparison of external costs of freight shipments by water, rail, and trucking. For air pollution in the form of particulates, for example, GAO (2011) estimates that trucking external costs are 6.7 times higher than those of rail and 10.2 times higher than those of water. While such comparisons are useful for providing a sense of national scale, they are only meaningful to the extent that one mode can substitute for another in specific origin–destination (O-D) markets. Moreover, national comparisons mask the subcorridor impacts where locally similar modal volume or intense activity by rail or inland water modes produces greater impact or provides higher benefits. As noted in Chapter 2, there are markets where truck and rail compete head-to-head and markets where rail and water compete, but trucking is involved in at least one segment of all freight moves and often two, and there are markets where the rail and water modes complement each other. Whereas trucks can serve almost all O-D pairs because of the ubiquity of roads and highways, and railroads reach many O-D pairs as well, barge transportation is limited by the availability of and access to navigable rivers and coasts. Thus, estimates of direct and indirect subsidies are meaningful in specific subcorridors for specific commodities.

Congress determine when federal spending is justified for new construction and major rehabilitation projects are based on the 1983 Economic and Environmental Principles and Guidelines for Water and Related Land Resources Implementation Studies (known as the Principles and Guidelines).22 The Principles and Guidelines prioritize the national net economic development benefit defined in terms of commercial navigation and operationalized as savings in shippers’ transportation costs.23

According to the most recent and wide-ranging attempt to catalogue and estimate the benefits of the inland waterways system, benefits beyond commercial navigation may include hydropower generation, recreation, flood damage avoidance, municipal water supply, irrigation, higher property values for property owners, sewage assimilation, mosquito control, lower consumer costs because the availability of barge shipping may result in more competitive railroad pricing (referred to as water-compelled rates), and environmental benefits associated with lower fuel emissions of barge compared with other modes (Bray et al. 2011). The available evidence on nonnavigation benefits that may result locally is incomplete and inconclusive. Bray et al.’s list includes many possible local benefits and national benefits. Some of the benefits may be viewed as transfers from one part of the economy to another. For example, in cases where lower rail rates may exist because of barge competition, the resulting savings in transportation costs are classified by USACE as a transfer to shippers (and a loss to rail lines), not a net national economic benefit. (See Box 3-2 for further discussion of the available research on the issue of water-compelled rates.)

________________

22 The Principles and Guidelines are available at http://planning.usace.army.mil/toolbox/guidance.cfm?Id=269&Option=Principles%20and%20Guidelines (accessed June 3, 2015). The Principles and Guidelines remain in effect. They were issued by the federal Water Resources Council, a body that no longer exists. In the Water Resources Development Act of 2007, Congress instructed the Secretary of the Army to develop a new set of Principles and Guidelines for USACE. However, these guidelines have long been under review and are viewed as controversial. The new guidance, if implemented, would have no effect on how the national economic development benefit is calculated for commercial navigation.

23 Shipper savings are measured as the difference in costs between moving a volume of a commodity from an origin to a destination by using the waterway for all or part of the movement and moving the same commodity without using the waterway. Shipper savings may also be realized if the alternative results in a reduction in scheduled or unscheduled lock unavailability for moving the commodity by using the waterway for all or part of the movement. Estimation of the benefits of reducing unscheduled unavailability requires prediction of the probability of the facility being unable to pass traffic, and the estimate is a function of a condition assessment for the facility. USACE has well-developed procedures for making such benefit and cost calculations (Engineer Regulation 1105-2-100).

BOX 3-2

The Issue of Water-Compelled Rates

Analysts have built models to demonstrate how water-compelled rates should play out in theory (Anderson and Wilson 2008). Some theory and empirical evidence indicate that rail rates are lower the closer the water alternative is to the shipper (McMullen 1991; MacDonald 1987; Burton and Wilson 2006; Harbor 2009; Burton 1993; Burton 1995). However, McMullen (1991) and Burton (1993) find that intramodal competition (presence of a second railroad) may also help explain the constrained rail rates. Furthermore, Burton and Wilson (2006) find that for situations in which a segment of the rail network competes with barge and then connects to a rail monopoly segment, the rail rates on the segment with barge competition may be lower, but the rail rates on the monopoly segment are often higher than comparable rail-only monopoly segments for the same commodities. Thus, the shipper likely receives no net benefit in these cases. The evidence also indicates that shippers of bulk commodities need to be relatively close to navigable rivers to benefit from water-compelled rates. Harbor (2009) found that the further a shipment originates from water competition, the higher the rail rate. Corn shippers located 100 miles from a barge loading point pay 18.5 percent higher rail rates than those located 50 miles from water. Soybean shippers located 100 miles from water pay rail rates 13.4 percent higher than shipments originating 50 miles from a barge loading point. When shippers require movement of their commodities to the river by truck or short-line railroad, they must balance the cost of these movements and transfers with the benefit of an all-rail movement.

According to economic principles, the most efficient way to allocate resources would be for the price of the mode to be set according to its marginal cost and for the market to decide the shares of freight to be carried by each mode (see Chapter 5 for further discussion). However, shippers of bulk commodities contend that without barge transportation there is insufficient competition for transportation of their commodities to ensure efficient resource allocation. Specifically, many coal and agricultural shippers and receivers assert that they are “captive” to a single railroad that can exercise market power in the setting of rates and that a water alternative is needed to protect them from monopoly rates. Congress has been sensitive to this

argument. After deregulating the railroads in 1980, Congress directed the Interstate Commerce Commission [and later the Surface Transportation Board (STB)] to balance the interests of railroads and shippers in cases with insufficient competition. The technical and policy issues concerning the performance of STB are complex. A study in parallel with this one is under way to examine STB’s performance and suggest reforms to address shipper concerns.

A possible national benefit of investing in the inland waterways is the environmental advantage that barge may have over other modes: barge’s lower fuel usage per ton-mile than other transportation modes may result in lower air emissions. Whether barge or rail is the more energy-efficient mode (measured as fuel use per ton-mile) depends in large part on the water route, since the increased circuity of some rivers offsets the reduced energy required to move products by water (see Appendix G for details of the committee’s assessment of the available research and its examination of data for selected major corridors). A comprehensive analysis at the subcorridor level would be needed to obtain a better understanding of the magnitude of the benefit. Challenges of such an analysis would be (a) the difficulty of modeling the potential for commodities to shift modes and (b) accounting for the comparative reliance on truck movements to and from the water and rail modes. Both rail and water can depend on trucks to move commodities from the origin to the rail or water terminal and from the rail or water line-haul movement to the ultimate destination. Since trucking involves much greater energy and emissions per ton-mile than either water or rail (GAO 2011), the distances of commodity movement by truck to the true origin and destination affects the net energy and emission benefits of movement by either mode.

A full assessment of environmental benefit would also need to account for the environmental damages associated with maintaining waterways for navigation. The mitigation of environmental costs is considered in benefit–cost analyses for construction and major rehabilitation

projects for which it is classified as an aquatic ecosystem benefit, understood as restoration of some of the preproject conditions with regard to pattern and timing of river flows that may result from changes in a facility.24

Congestion reduction is another possible environmental benefit of barge, and one that USACE may include in benefit–cost analysis, but it is difficult to assess. A reduction in congestion may be realized if the availability of barge results in traffic shifts from an alternative mode to the waterways. The initial assumption of the investment analysis typically is that the alternative modes—rail, highway, and pipeline—have sufficient capacity to continue to move traffic at current rates without the waterway improvement and that congestion reduction could not be a benefit. For that assumption to be modified, USACE’s analysis would need to show congestion on some other mode, demonstrate how the shift to waterway would reduce that congestion, and then evaluate the beneficial effects of congestion reduction. Environmental Protection Agency models might then be used to estimate the impact of such a change in highway traffic on emissions. Models are available for predicting the impact of such traffic diversions on safety. However, all of these estimates depend on the accurate prediction of traffic diversion, which requires realistic estimates of how much modal shift will take place even if costs change substantially. To monetize the impact of the investment on congestion reduction requires assigning a dollar value to time (for congestion time savings), to costs of accidents (including a value for lives saved), and to emission reduction effects on human health and ecosystems. If such effects can be identified, ranges of dollar values may be used for estimates, but there may be considerable disagreement as to the monetary size of these impacts.

In addition to possible reductions in emissions and congestion, oil spill and safety advantages may result from shipping by barge (Frittelli

________________

24 If the restoration was an outcome of a project investment, USACE’s procedures would allow that benefit to be claimed and made part of the project cost justification, even though such river restoration benefits are not monetized. However, the more common claim is that inland waterway project investments for commercial navigation are detrimental to the aquatic ecosystem. When that is the case, the alternative must include actions to mitigate the unavoidable adverse impacts on the aquatic environment, and the costs of those actions are part of project cost. For facilities no longer operated for commercial navigation, restoration of preproject conditions would be a priority.

2014; Frittelli et al. 2014; GAO 2011). The policy question for deciding on the federal role in funding the system is not whether environmental benefits exist from moving freight by barge, but whether the size of the benefits warrants current levels of federal investment required to obtain them. On this question the evidence is uncertain because a definitive study has not been done. As noted above, a Transportation Research Board committee concluded that development of reliable estimates of the marginal costs of shipments by truck, rail, and barge would be possible and recommended a study to allow generalizations that could inform decisions about the size of federal support for surface freight transportation (TRB 1996). However, federal agencies have declined to fund the data collection and analysis that would be required to develop complete and policy-relevant conclusions.

ECONOMIC AND PRACTICAL CONSIDERATIONS IN DECIDING ON CHARGES FOR BENEFITS

In view of the constraints on federal funds and the importance of O&M in the inland navigation budget, Congress and the executive office will need to decide how to pay for the system and how to prioritize inland waterways expenditures versus other federal expenditures. Economic principles for charging system users and the practicalities of implementing charges for the benefits received are important considerations in an analysis of how to fund the system.

According to economic principles, if beneficiaries impose either marginal costs or opportunity costs, user charges will improve economic efficiency (Chapter 5 describes the economic rationale for user charges in more detail). A next step would be to determine whether efficient or practical ways exist to charge groups of users who impose significant costs for the costs associated with their use of the system. The various beneficiaries can be grouped into four classes: commercial navigation, flood control and hydropower, ancillary, and environmental.

Commercial Navigation Beneficiaries

This group is a direct beneficiary and imposes marginal costs to obtain these benefits. Chapter 5 presents options for charging users for commercial navigation and criteria for deciding among the options. User

charges for the system have been proposed since the 1940s, which the shipping industry has consistently opposed. Supporters of user charges have included OMB, the Government Accountability Office, and Presidential administrations of both parties since Roosevelt, both before and after implementation of the first fuel tax approved by Congress in 1978 (see Box 3-3 for a brief history of proposals for user charges).

An increase in charges for shippers using the waterways raises concern about a resulting shift of cargo from water to rail and highway, perhaps accompanied by negative effects on highway congestion, noise, air quality, safety, and wear and tear on highways. Analysis of the possible mode shift from temporary closure of a waterway indicates, in the case examined, that, of the tonnage that would shift, most would move to rail and little to truck (Kruse et al. 2012). Moreover, after the start of the diesel fuel tax, several studies of the potential impact of the barge diesel fuel tax on barge freight were conducted in the 1980s. The consensus conclusion of these studies was that any diversion of barge freight to rail would be minimal. For example, Babcock and German (1983) found that a 100 percent cost recovery user fee would divert only 4 to 5 percent of barge tonnage to railroads. However, as noted in the discussion of the potential for mode shift in Box 2-1, the shift from one mode to another is highly dependent on commodity, distance, subcorridor infrastructure, cost, and other variables, which makes generalizations difficult. The policy question that arises in deciding the federal role is whether the emission, safety, highway congestion, and infrastructure costs are greater than the costs of preventing them.

Flood Control and Hydropower Beneficiaries

Bray et al. (2011) include flood control and hydropower as beneficiaries of inland navigation. For projects that support commercial navigation as well as other purposes such as flood control, the cost of serving that purpose is allocated as described in Table 3-1. The beneficiaries of some purposes (e.g., hydropower) pay directly for their allocated cost, and some purposes are paid for via general revenues (e.g., flood control). As a result, commercial navigation is allocated the costs attributable to that purpose, and the other purposes are allocated

BOX 3-3

Brief History of Proposals for User Charges for the Commercial Inland Waterways Systema

The Constitution (Article 1, Section 8) gives Congress power to regulate commerce, including navigation and navigable waterways. Section 10 of the first article protects the freedom of commerce throughout the country by prohibiting the laying of “any duty of tonnage” to carry out that intent. Furthermore, Congress instituted a free waterway policy for the new Northwest Territory in the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. It declared that navigable waters leading into the Mississippi and Saint Lawrence and those of any other states that may be admitted into the Confederation “shall be common highways and forever free . . . without any tax, impost, or duty therefore.” Later legislative acts from 1790 to 1803 extended these exemptions to the territory south of the Ohio River and declared that navigable rivers were public highways.

During this period, Congress limited initial federal financial investments in the inland waterways system to snagging and clearing operations. These were modest actions taken to support free use during the colonial period because of the importance of inland waterways to the early geographical and economic expansion of the nation. States undertook the expensive construction of canals, locks, and dams and made other improvements for navigation. States often charged tonnage duties and tolls for waterways use but were still unable to finance large navigation expenditures. Private enterprise also had difficulty in recovering the costs of water transport investments, especially after railroads emerged as competition.

By the 1940s, a transportation system had emerged that included both water and rail carriers. The federal policy of subsidizing commercial navigation began to be questioned (U.S. Office of the Federal Coordinator of Transportation 1939, 125). Highway transport also was emerging, but not yet for long-haul movements. The Franklin Roosevelt administration of 1940 was the first to consider seriously the idea that modifying the policy of free inland water transportation to recover the costs of providing for navigation was allowable and feasible. Since the Roosevelt administration, user

________________

a Box 3-3 draws from Ashton et al. (1976) and Shabman (1976).

charges as a funding source for the inland waterways have been proposed or supported by presidents of both parties. The President’s Water Resources Policy Commission (1950, 202–203) under President Truman was consistent with the position of the Roosevelt administration, illustrated as follows:

Decisions as to user charges, or tolls for water commerce should be worked out as part of the whole problem of reconciling and making workable a coordinated transportation system. But with rates from all forms of transportation based on full costs, an interconnected system of modern waterways, coordinated with land transportation, should be able to sustain itself with tolls based on full costs and yield returns on the public investment, while contributing to most economic use of the Nation’s resources.

In 1956, President Eisenhower submitted a report favoring some type of user charges with regard to the cost of O&M (Senate Committee on Commerce 1961, 32). In 1962, President Kennedy proposed user payment for the inland waterways and suggested a fuel tax of $0.02 per gallon. President Johnson reiterated President Kennedy’s proposal in his budget messages and recommended a fuel tax that would extend to all domestic vessels with a maximum draft of 15 feet or less. The Carter administration also indicated support for some form of user charge.

In 1978 and 1986 Congress passed the two pieces of legislation that began to transform funding for the inland waterways and created the funding framework followed today. This legislation established the fuel tax on commercial barges, increased user cost-sharing requirements, and established the IWTF to fund construction with fuel taxes paid by the barge industry. The industry opposed the lockage fees to fund construction and maintenance proposed in the Inland Waterways Revenue Act of 1978; this opposition led to the current fuel tax, which is less directly tied to the usage of waterways facilities and pays for construction and not maintenance.

A number of proposals have been made more recently by both the Bush and Obama administrations to change user payments to recover the system costs associated with commercial shipping (see Chapter 5).

costs specific to their use. Hence, beneficiaries of nonnavigation purposes are expected to pay their allocated share and are not an additional source of funding for supporting the commercial navigation purpose within multipurpose projects. If the navigation function were to cease for these multipurpose projects because of minimal or no traffic, the other project purposes would be allocated the costs of the project. If the whole project was decommissioned, the federal government would be responsible for either removing the project or paying to make sure it would not fail in a weather-related or other event. In the case of hydropower, the beneficiaries already pay for the O&M costs associated with their use of the system and a share of the capital costs. For the commercial navigation projects that also provide hydropower, the hydropower beneficiaries pay 100 percent of capital costs allocated to hydropower and any allocated costs for operations. If the navigation function ceased for these waterways, hydropower beneficiaries would have to pay to maintain the dams to continue to receive this benefit.

Ancillary Beneficiaries

Groups that receive other benefits from projects authorized for commercial navigation are referred to as ancillary beneficiaries because they were incidental to the purpose for which these waterways investments were made. Municipal water supply, slack water boating, and landside recreation are possible ancillary benefits recognized by USACE. A more comprehensive assessment of these benefits and their levels could be undertaken, but even if the benefits proved to be large, the marginal and opportunity costs to navigation imposed by these users of the system are minimal. Furthermore, a practical way of charging these users does not exist, because they cannot be excluded from receiving the benefit of waterway projects maintained for commercial navigation if they do not pay. This case refers to segments used for commercial navigation; if maintenance for navigation ceased because of minimal or no commercial navigation traffic, the ancillary users would become the primary users and may be charged for their benefits. Chapter 5 provides further discussion of this case.

A possible exception is recreational boats that could be charged a fee for the operation of locks on waterways used for commercial

navigation. Pools behind dams permit boating, fishing, and other water-based recreation. Lockages are required for recreational craft to pass between pools. Recreational lockages impose marginal costs on the lock and dam system. Lockage service can increase financial outlays for system operations, increase wear on the lock itself, and cause traffic delays. USACE has adopted a number of management measures to reduce commercial navigation delay cost (for example, scheduling of limited times for recreational boat passages), but financial costs are still incurred. USACE could calculate the costs of providing recreational lockages across the system, and if justified, Congress could choose to increase the inland waterways budget by that amount or authorize USACE to base a recreational user fee on that cost. This user fee is discussed further in Chapter 5.

Environmental Beneficiaries

If environmental benefits are sufficiently sizable and broadly distributed, taxpayers would be the beneficiary. As explained earlier, environmental benefits of inland navigation exist, but the magnitude of the benefit is uncertain. As a practical matter, the challenge of paying for the benefit in the context of federal budget constraints persists, leading back to a consideration of other funding options.

The inland waterways system infrastructure is managed by USACE and funded from the USACE budget. Funds available for inland waterways navigation are in decline in constant dollars. As the system has aged, maintenance has become a higher priority and now accounts for about three-fourths of the administration’s inland navigation budget request.

Federal general revenues cover most of the cost of the inland waterways system. Users pay a share of construction costs through a barge fuel tax, but none of the cost of O&M. System users recognize that they need to pay more. The 113th Congress and the shipping industry supported a $0.09-per-gallon increase in the barge fuel tax in 2014. However, under federal legislation, fuel tax revenues can

be used only to pay for construction; they cannot be used for O&M. While the amount of funding required to sustain reliable freight service is not clear, it is evident that total revenues after the increase in the fuel tax will not be sufficient to maintain the system.25 Furthermore, increased capital funding from users would compete with available federal funding for O&M, since the federal government must both match the user contribution for capital improvements and pay all of the costs of O&M.

Because of historical precedent, the federal role in the management and funding of the inland waterways for commercial navigation is already greater than for other freight modes. The total federal share of the cost of the inland waterways system is estimated to be about 90 percent (TRB 2009). The federal share is roughly 25 percent for the highways used by motor carriers and 0 percent for pipelines and nearly so for railroads (both private industries for which the federal role is primarily one of safety and environmental regulation). Whereas federal general revenues cover all O&M expenses for the inland waterways, states pay 100 percent of the O&M expenses, mostly from user fees, for intercity highways used by motor carriers. O&M expenses for railroads and pipelines are paid for by the private industries responsible for these modes.

In a climate of constrained federal funds and with O&M becoming a greater part of the inland navigation budget, a pressing policy issue is how to pay to preserve the system. Examination of whether beneficiaries could help pay for the system is rational and would improve economic efficiency. Commercial navigation beneficiaries are a viable option, since commercial carriers impose significant marginal costs (Chapter 5 discusses options for these user charges and criteria for deciding among them).

Flood control and hydropower beneficiaries are not options for additional funding for commercial navigation projects. The cost of flood control for the few commercial navigation projects that provide a flood control benefit is allocated for that purpose and paid via

________________

25 It is possible, though not likely, that federal budgets will grow substantially over time with significant increases for inland navigation, but the committee assumes a more modest budget consistent with observed trends and the policy goal of efficient use of resources with or without budgetary constraints.

general revenues. For the few commercial navigation projects that also provide hydropower, hydropower beneficiaries already pay 100 percent of new capital costs and any marginal costs for operations of benefits they receive. Practical mechanisms or economic reasons do not appear to exist for charging ancillary beneficiaries of waterways projects used for commercial navigation (municipal water supply, irrigation, higher property values for property owners, sewage assimilation, mosquito control, and recreation), with the possible exception of charging for recreational boat lockages. Ancillary beneficiaries may be charged for waterways with minimal or no commercial navigation since in this case they would become the primary beneficiaries. (This case is discussed further in Chapter 5.)

Barge transportation may provide an environmental benefit to the larger public that includes lower emissions, safety, spills, and congestion, but whether the size of the benefit is in line with the current level of federal investment is uncertain. Further analysis of corridors would be needed to quantify the benefit. In the absence of definitive evidence concerning the size of inland waterways benefits and until such evidence becomes available, Congress and the executive branch will have to use their best judgment in determining the share the federal government should pay and how to prioritize these expenditures versus other federal expenditures.

Regardless of who pays for the system, a process is needed for prioritizing spending. The capital projects backlog is not a reliable indicator of the amount of funding required for the system. A modest amount of the backlog is for navigation projects. A portion of the navigation backlog includes major rehabilitation to maintain the system, but it does not include O&M. Furthermore, the navigation backlog may include projects that are a lower priority for spending. Congress has long authorized and appropriated USACE capital projects on a project-by-project basis. A benefit–cost analysis prepared by USACE is the primary source of technical information that Congress uses during the authorization process in deciding when spending is justified for capital projects. While benefit–cost analyses have been used for determining whether a project meets a minimum threshold for funding, they have not been used to rank projects, and the result has

been far more projects being authorized than can be afforded within the constraints of the budget. A method for prioritizing projects on the basis of the service needs of the system would be more useful than an attempt to estimate and seek funding for the existing backlog. (Chapter 4 discusses an approach for prioritizing spending, with an emphasis on O&M.)

References

ABBREVIATIONS

| CBO | Congressional Budget Office |

| CRS | Congressional Research Service |

| GAO | Government Accountability Office |

| NRC | National Research Council |

| TRB | Transportation Research Board |

Anderson, S., and W. Wilson. 2008. Spatial Competition, Pricing and Market Power in Transportation: A Dominant Firm Model. Journal of Regional Science, Vol. 48, No. 2, pp. 367–397.

Ashton, P., C. Cooper Ruska, and L. Shabman. 1976. A Legal–Historical Analysis of Navigation User Charges. Journal of Water Resources Planning and Management Division, Vol. 102.WR1, April, pp. 89–100.

Babcock, M. W., and H. W. German. 1983. Forecast of Water Carrier Demand to 1985. Proc., 24th Annual Meeting of the Transportation Research Forum, Vol. 24, No. 1, pp. 249–257.

Bray, L. G., C. M. Murphree, and C. A. Dager. 2011. Toward a Full Accounting of the Beneficiaries of Navigable Waterways. Center for Transportation Research, University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

Burton, M. 1993. Railroad Deregulation, Carrier Behavior, and Shipper Response: A Disaggregated Analysis. Journal of Regulatory Economics, Vol. 5, pp. 417–434.

Burton, M. 1995. Rail Rates and the Availability of Water Transportation: The Missouri Valley Region. Review of Regional Studies, Vol. 25, No. 1, pp. 79–95.

Burton, M., and W. W. Wilson. 2006. Network Pricing: Service Differentials, Scale Economies, and Vertical Exclusion in Railroad Markets. Journal of Transport Economics and Policy, Vol. 40, No. 2, pp. 255–277.

Carter, N. T., and C. V. Stern. 2011. Army Corps Fiscal Challenges: Frequently Asked Questions. Congressional Research Service, Washington, D.C.

Carter, N. T., and C. V. Stern. 2014. Army Corps of Engineers: Water Resource Authorizations, Appropriations, and Activities. Congressional Research Service, Washington, D.C.

CBO. 2014. The Highway Trust Fund and the Treatment of Surface Transportation Programs in the Federal Budget. United States Congress, Washington, D.C. http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/45416-TransportationScoring.pdf.

Dager, C. A. 2013. Fuel Tax Report, 2011. Center for Transportation Research, University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

Ferejohn, J. A. 1974. Pork Barrel Politics: Rivers and Harbors Legislation, 1947–1968. Stanford University Press, Stanford, Calif.

Frittelli, J. 2013. Harbor Maintenance Finance and Funding. Report R43222. Congressional Research Service, Washington, D.C.

Frittelli, J. 2014. Shipping U.S. Crude Oil By Water: Vessel Flag Requirements and Safety Issues. Congressional Research Service, Washington, D.C.

Frittelli, J., A. Andrews, P. W. Parfomak, R. Pirog, J. L. Ramseur, and M. Ratner. 2014. U.S. Rail Transportation of Crude Oil: Background and Issues for Congress. Congressional Research Service, Washington, D.C.

GAO. 2010. Army Corps of Engineers: Budget Formulation Process Emphasizes Agencywide Priorities but Transparency of Budget Presentation Could Be Improved. GAO-10-453.

GAO. 2011. Surface Freight Transportation: A Comparison of the Costs of Road, Rail and Waterways Freight Shipments That Are Not Passed On to Consumers. GAO-11-13.

GAO. 2012. Highway Trust Fund: Pilot Program Could Help Determine the Viability of Mileage Fees for Certain Vehicles. GAO-13-77. http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-13-77.

Harbor, A. L. 2009. An Assessment of the Effect of Competition on Rail Rates for Export Corn, Soybean, and Wheat Shipments. Journal of Food Distribution Research, Vol. 40, No. 1, pp. 70–78.