3

Health Literate Digital Design and Strategies

The workshop’s first panel session featured three presentations, then reactions to those presentations by representatives of the entrepreneurial private sector, the foundation world, and government. Rebecca Schnall, assistant professor of nursing at the Columbia University School of Nursing, described the use of rigorous, user-centered design methods to understand the needs of a mobile app for HIV prevention among high-risk men who have sex with men. Read Holman, program director and senior advisor on internal entrepreneurship at the HHS Innovation, Design, Entrepreneurship and Action (IDEA) Lab in the Office of the Chief Technology Officer at HHS, discussed the federal government’s digital strategy as a framework for spurring health literacy. Alex Krist, associate professor of family medicine and population health at Virginia Commonwealth University, spoke about patient portals as an example of a consumer-facing health technology. The three experts who commented on these presentations were Dean Hovey, an experienced entrepreneur and currently president and chief executive officer of Digifit; Catina O’Leary, president and chief executive officer of Health Literacy Missouri; and Lana Moriarty, director of the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology’s (ONC’s) Office of Consumer eHealth. An open discussion moderated by Susan Bakken, alumni professor of nursing and professor of biomedical informatics at Columbia University School of Nursing, and Bernard Rosof, followed the presentations and reactions.

DESIGN SPECIFICATION FOR APPS: A CASE STUDY1

To begin her presentation, Schnall said she was going to highlight a different approach to app design, one that involved speaking to end users and thinking about behavior change before starting the design process. This approach, she said, contrasts with the way most health-related apps have been designed, which is to create the app, put it into the app store, and then see if it gets used and helps change behavior. She noted that while mobile health technology has the potential to change health-related behaviors, there is little research evidence to date to support how these technologies can change health behaviors and outcomes in a meaningful way over the long term. She also pointed out that current estimates show some 40,000 apps are available that focus specifically on health-related activities and outcomes.

The goal of her group’s work, which was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), was to use rigorous, user-centered design methods to understand what features were most needed in a mobile app for HIV prevention aimed at high-risk men who have sex with men. This population continues to experience an increase in the number of new HIV infections, particularly in young Latino and African American men, despite the fact that the number of new cases in the American population in general has remained constant over the past few years. “We need something to target this population,” said Schnall, and given the age of the target population, mobile health technology in the form of an app should be an appropriate venue for delivering health information. “Many of our participants were in low socioeconomic groups, but even though they’re not really sure where they’re getting their next lunch or where they’re going to sleep tonight, they all have a smartphone,” she explained.

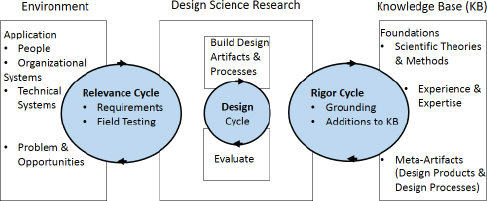

The design framework she and her colleagues used is based on design science, a systematic form of designing with three iterative cycles: a relevance cycle, a design cycle, and a rigor cycle (see Figure 3-1). Not many of the 40,000 available mobile health apps or health information technology systems that are built today take all of these of these areas into consideration, Schnall explained, and some do not consider any of these aspects in their design. To identify the environmental factors that they needed to consider when designing this app, Schnall and her colleagues conducted focus groups with potential end users. They then looked at the existing knowledge base and identified what methods had already been used and tested for HIV prevention in terms of mobile health applications. They also

_______________

1 This section is based on the presentation by Rebecca Schnall, assistant professor of nursing at the Columbia University School of Nursing, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the IOM.

FIGURE 3-1 An information systems research framework used to design an end-user-focused app.

SOURCE: Schnall presentation, March 24, 2015.

considered how to test the app so they could determine how end users were able to use it and whether it was effective at changing behavior.

Going into more detail, Schnall explained that she and her colleagues conducted a series of 5 focus groups involving 33 high-risk men who have sex with men of ages ranging from 13 to 64. The focus groups included whites, African Americans, and Latinos, with one group consisting of only Spanish speakers. The results, said Schnall in response to a question, were largely congruent among the groups. A thematic analysis of the focus group sessions revealed five broad categories of what the participants wanted in an app:

- Information management, or the ability to manage their own health information, such as the time of their most recent HIV test or physical;

- How to stay healthy, including information on diet and exercise;

- HIV testing information;

- Chat or other communication functions that would enable them to stay in contact with peers, health counselors, and health care providers; and

- Access to resources.

With the relevance cycle complete, Schnall’s team conducted activities related to the rigor cycle, which included an environmental scan of the existing literature related to both mobile health interventions and electronic health interventions that had been used with high-risk men who have sex

with men to target HIV prevention behaviors. One goal of this literature review, which included both the peer-reviewed and grey literature (Schnall et al., 2014), was to find out about existing apps and the degree to which any of them had been studied. “Of the studies that we did include in our systematic review, there have been no rigorous studies of mobile health interventions in the study population,” said Schnall.

The final cycle, the design cycle, had two components: the develop/ build and evaluation phases, with activities centered on creating a highly usable app that incorporated the five categories of what users wanted in an app. As part of the design phase, Schnall and her colleagues conducted two 90-minute design sessions with the same group of 6 participants, ages 20 to 25, who were asked to tell the developers what the app should look like given the 5 broad categories. As an example of the responses in the first design session (see Table 3-1), the participants said they wanted a log of past partners to be part of the information management category so that if they tested positive for HIV at a later date, they could communicate with past partners if they so desired.

With regard to HIV testing, the participants had novel and innovative suggestions of the things they needed, said Schnall. “They all know that you need to get tested for HIV, but they had deeper health information needs as well as functionality for their app that were things we hadn’t thought of ourselves as researchers,” she said. For example, the participants said they not only want HIV testing site information, they wanted a global positioning system (GPS) location on how to get to the site, other users’ rating of the site, and wait times at that site. They also wanted information on the difference between anonymous and confidential testing.

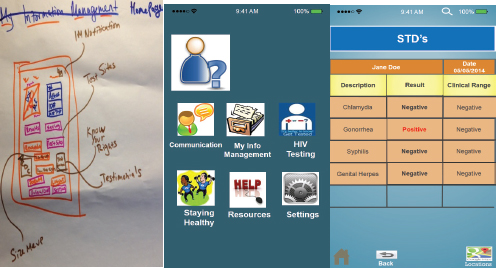

Following that first design session, at which all of the discussions were recorded, the researchers coded a first iteration of the app. They then held the second design session to get input from the participants on the user interface. Over a 2-hour session, the participants discussed what they wanted the app to look and feel like. After reviewing existing apps and splitting into two groups of three, the participants drew pictures of what the app user interface should look like (see Figure 3-2) and the researchers created mock-ups using PowerPoint for comment by the participants.

Next, the researchers conducted two types of usability assessments, both heuristic evaluation and end-user usability testing, on one of the mock-ups. Heuristic evaluation was conducted with informaticians and others who have expertise in user interface, design, usability principles, errors, and other important factors. End-user usability testing was conducted with high-risk men who have sex with men who were also given use cases to guide them in testing the mock-ups. Based on the heuristic evaluations, the researchers made 112 changes to the mock-up over 5 iterations, while end-user usability testing led to 55 more changes. Schnall said

| Topic Area | What | How |

| My Information Management | Log of Past Partners | Date, HIV Status, Rating of Experience |

| Staying Healthy | HIV Information | Videos |

| Current Scams | ||

| Prevention | HIV Risk Assessment Tool | |

| Updates on Pre-Exposure (PrEP) Studies | ||

| Condom Size and Type Selector | ||

| Diet/Fitness | Body Mass Index Calculator | |

| Exercise Tracker | ||

| HIV Testing | HIV Testing Site Info | Global Positioning System (GPS) Location |

| Rating | ||

| Cost | ||

| Waiting Time | ||

| Testing Log | Picture of Test Results | |

| Last Date Tested | ||

| Chat/Communication | Medical Providers | Contact for PrEP |

| Link to Emergency | ||

| Contact/Resources | ||

| Live Hotline | ||

| Social/Peer | Forums for Social Support | |

| Social Media Links | ||

| Resources | Support Group Locations | Voice Activated “Siri” |

| GPS Mapping | ||

| Condom Distribution Locations | GPS Mapping and Information on Condom Distribution Sites | |

| Latest HIV News | Newsfeeds | |

SOURCE: Schnall presentation, March 24, 2015.

SOURCE: Schnall presentation, March 24, 2015.

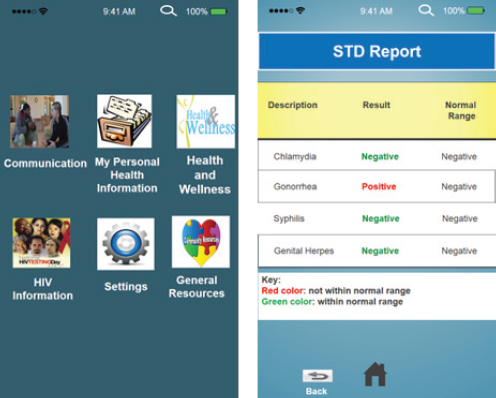

it was important that not all of the end users they recruited for usability testing were smartphone users, as each type of user provided valuable input that went into the final mock-up (see Figure 3-3). She also noted that the sexually transmitted disease report screen underwent the most remarkable changes, both in terms of the overall look of the page and the use of colors to denote the difference between a positive and a negative test result.

In closing, Schnall stressed the importance of making the design process iterative and of including input from end users about their needs. “We had our research team that was commenting and analyzing as we went through all this design process, but we also included our end users at every stage of the process in thinking about what our end product would be,” she said. In the end, the synthesis of end-user feedback with content expert advice provided the foundation for the development of a highly usable and useful app. In response to a question, Schnall added that she plans to build this app for both English and Spanish speakers and that she did not think that content in the two versions would differ much.

SOURCE: Schnall presentation, March 24, 2015.

THE FEDERAL DIGITAL STRATEGY AND HEALTH LITERACY2

Read Holman began his presentation by explaining that part of his role at HHS is to bring what he called “entrepreneurial methodologies” of the sort that are often associated with Silicon Valley into HHS. One of these entrepreneurial methodologies is known as lean start-up, which he said is fundamentally the principles of the scientific method brought to design. “It’s do we know what we are building is actually working,” he said. “How do we gather evidence, to build on the shoulders of giants if you will, but our giants just happen to be our end users?”

He then shared a brief anecdote to illustrate what he considers a good example of easy-to-use consumer-facing technology. While preparing his

_______________

2 This section is based on the presentation by Read Holman, program director and senior advisor on internal entrepreneurship at the HHS IDEA Lab in the Office of the Chief Technology Officer at HHS, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the IOM.

slides for this presentation, he struggled with what should have been a simple task of inserting page numbers onto each slide. Using the software’s help function got him nowhere, so like many others, he used Google to search for an answer. It appeared immediately without the need to even click on a link or scroll anywhere. What struck him about the ease with which Google provided him with an answer is that people do this every day for health-related questions. Intrigued, he typed “What is Huntington’s disease?” into the Google search box and again, the answer appeared. “I didn’t have to click on anything, I didn’t have to dive in through any website,” said Holman. “This is the consumer-facing technology that we’re all talking about.”

Turning to the subject of the federal digital strategy and how it applies to health literacy, Holman said developers of the strategy did not have health literacy in mind. Instead, the strategy was aimed at the larger world of digital government and the direction of the information technology industry and its impact on society. The document that lays out the federal digital strategy (The White House, 2012) breaks out four strategic principles:

- It should be information-centric, which focuses on the need for government to decouple the data and information layer from the presentation layer;

- It should have a shared platform, which focuses on the need for government to work better with itself;

- It should be customer-centric, that is, customers should be able to get their content anytime, anywhere, and on any device; and

- It must have strengthened security and privacy processes.

Going into more detail about the first principle, that data and presentation should be separate considerations, Holman showed a data-dense, difficult-to-read spreadsheet of all the hospitals in the United States that accept Medicare patients and called that data. He then showed two of the many ways of visualizing those data to illustrate the difference between data and presentation. By separating data from presentation, the digital strategy creates an important framework for creating and displaying information in a way that is centered on the user, not the data generator. This framework consists of the presentation and data layers plus a management layer that sits between the two and provides the mechanisms by which users can get into the data, the way in which the data are released, and then how the data get converted into a suitable presentation format. Each of these layers, said Holman, exists in its own world. Addressing each component separately allows for achieving the ultimate goal, which is to create a better experience for users and provide better service to the American people. He noted that

in the presentation layer, both the government and the private sector have roles to play in getting information from the government to the public.

The goal of creating this framework is to make data, whether they are numbers or words in a structured format, useful to the American people. With regard to the management layer, the goal is to provide easy access to the data through the development of application program interfaces and data formats while addressing concerns about privacy and security, Holman explained. The goal of the presentation layer is to provide excellent customer service and a great user experience. The latter is important, he noted, because the purpose of having a coherent digital strategy is to influence behavior. “Providing a useful and beautiful website is pointless if nobody is going to the website, or you’re not having an impact on their lives,” he said.

The federal government has many websites and most are “pretty ugly,” Holman said in acknowledging that the private sector is better at designing a great experience for consumers. Recognizing that fact, the federal government is focusing on the data and management layer. As an example, he referred the workshop audience to the website healthdata.gov, which is where the federal government makes available more than 17,000 datasets related to health. This is not a site aimed at the American consumer, but rather those who want to create content and make information available to their customers.

Another example Holman discussed involved content syndication, the notion that content can be created once and then published by others on their own websites. CDC, for instance, prepares a wide range of Web-based information that is designed for publication on both private sector and government agency websites in a way that best meets the needs of those content providers through their ability to adjust the presentation layer. Holman also highlighted the “Blue Button” initiative, which is intended to allow every American to go online and download his or her health records and use that information for health improvement (Turvey et al., 2014).

In focusing on the data and management levels, the government aims to support the private sector in meaningful ways, such as by providing guidance and standards and by publishing research. As part of this effort, the government has created a set of challenges and prizes as a means of providing incentives to the private sector to develop new ways of presenting information to the American public. These challenges, authorized as part of the America Competes Act, have spurred competition in the private sector to create novel user experiences from the data that the government makes available. One challenge, for example, was to create an attractive patient record that an individual can download using the Blue Button. More than 230 developers responded, producing what Holman characterized as a number of beautiful and inspiring examples of apps and websites for displaying patient records.

Holman explained that while the government is publishing standards and guidance to help the private sector, and is largely leaving presentation-layer development to the private sector, it will jump in when the private sector is not succeeding in a particular area. In those cases, the government uses best practices from the literature and the start-up world and focuses on using iterative design methodologies that involve interacting with customers and patients. In the best cases, the iterations are small and the process grows a presentation format in collaboration with the end user. When this process is done using the scientific method, said Holman, the outcome will be a good-looking, usable, and useful product that serves the American people and drives behavior. He noted that government websites are increasingly being built using this approach to responsive design to produce websites, mobile apps, and tablet apps that are consistent in the way they present information.

In what he called a quick note about a data-driven future, Holman quoted President Obama, who said, “We want every American ultimately to be able to securely access and analyze their own health data so that they can make the best decisions for themselves and for their families.” Meeting this goal will be difficult without health literate, consumer-facing technologies, for most Americans are not going to download their entire patient record, create macros in Excel, and analyze their data. Instead, consumers will rely on presentation layers such as the Google search page and Apple’s Siri interface to create a user-friendly, usable experience. He commented that asking Siri the question “What is Huntington’s disease?” produces the Wikipedia entry, but other queries, such as “How many calories have I burned?” produce fewer satisfying responses today. The question, said Holman, is “How can we get to that place where the one consumer-facing technology is that personal digital assistant?” The answer, he added, is near. In closing, he noted that the only way to ensure that the right data and the right information are getting to the consumer is to turn to the data layer and to ensure that the data are structured in a way that massive algorithms and search engines can digest them and present them to the user in a manner that is both informative and that changes behavior.

Alex Krist, who is both a practicing family physician and researcher, has been trying over the past decade to make patient portals more patient centered and to create an experience for patients that enables them to both

_______________

3 This section is based on the presentation by Alex Krist, associate professor of family medicine and population health at Virginia Commonwealth University, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the IOM.

access their health information and get advice based on that information about what they need to do to stay healthy. He noted before proceeding that he is a member of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), but that he would be talking about the work that he and his colleagues in Oregon, at the University of New Mexico, at Virginia Commonwealth University, and in the Office of Health Promotion and Disease Prevention have been doing, and not as a representative of the task force.

When thinking about patient portals, one fact to keep in mind is that two-thirds of primary care practices now use EHRs and 60 percent are participating in meaningful use, which means that they need patient portals. What this means for patients, explained Krist, is that they might have distinct portals with their primary care doctor, their specialists, the radiologist, the insurance company, and the laboratory company. He noted, in fact, that he had to register his daughter for a portal for an outpatient surgery center before she had surgery. The availability of so many portals, each with its own design, can create a situation that is challenging for patients to negotiate. At the same time, patients want to do many tasks with their portals, such as examining their EHRs to make sure they are correct, tracking expenses, avoiding duplicate tests, keeping their doctors informed of what is going on with their health, managing their families’ health status, getting treatments that are tailored to them personally, and managing their health and lifestyle. Moreover, they want to be able to move from doctor to doctor, care setting to care setting, and take all of this information with them.

What portals are actually doing for patients is another matter, said Krist. To a large extent, he said, they function simply as a window to look at a patient’s physician record, and those records are written in doctor language. “It’s hard for doctors to understand what’s in that information and unreasonable to expect patients to understand that information,” said Krist. So while patients can see their lists of diagnoses, medicines, allergies, test results, and the like, and sometimes even doctors’ notes, patients are often limited in what they can then do with this information. Laboratory results, for example, are often accompanied by reference ranges that do not apply to all patients and usually refer to worst case scenarios.

In addition, guidelines are becoming increasingly complex, making it difficult for patients to know what to do to improve their health even with the information in their health record. For example, the USPSTF makes a recommendation on the use of aspirin to prevent heart attacks, and this guideline says that a man age 45 to 79 should take aspirin if the benefit of preventing a heart attack outweighs the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding that can result from aspirin therapy. “That’s tremendously difficult for a doctor to interpret, let alone a patient to interpret, who wants to know should I take an aspirin or should I not take an aspirin,” said Krist. To be fair, he added, these USPSTF guidelines are meant for clinicians, not

patients. He also noted that the task force is creating consumer-directed guides and that doctors’ portals are trying to help patients make sense of these guidelines, though often physicians need to configure alerts, such as when their patients are overdue for immunizations.

Krist and his colleagues have been struggling with how to help patients truly understand the preventive care they need to stay healthy and to take action on that information. Their quest to solve those problems began with a series of grants that started in 2007 and has benefited from collaboration with the healthfinder.gov staff. The healthfinder.gov website was created with a user-centered design approach that includes formative and usability testing involving more than 700 patients, some of whom were of low literacy. It is also evidence based and the patient can tailor the site based on age and gender. As an example, Krist said that a woman can enter that she is pregnant. In turn she will receive a list of all of the preventing services that are covered by the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and that the USPSTF and other groups recommend. This design is based on the Health Literate Care model, Krist explained, and takes a universal precautions approach that assumes that everyone is at risk for not understanding the information. Even with taking a universal precautions approach, he noted, patients can take away different meanings than what health care professionals intend.

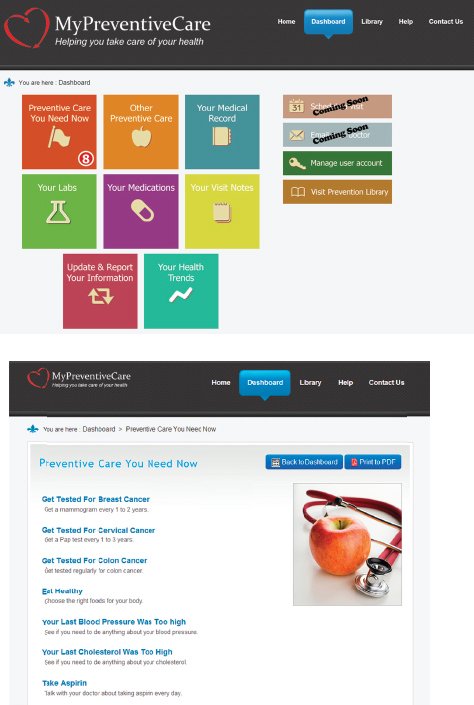

Taking this approach one step further, Krist’s team is attempting to link into doctors’ EHRs, make sense of the data there, apply national guidelines, and generate concrete advice in patient-centered terms that are specific for each individual. The result is MyPreventiveCare, which aims to translate into lay language all of the information in guidelines as applied to the information in each patient’s EHR. This is done using an application that is embedded into patient portals and that takes the content of a patient’s EHR, applies clinical information to that content, and produces advice in a user-friendly form that can go from prevention to disease management, with links to additional information on each piece of advice (see Figure 3-4). “I often liken it to the doctor sitting next to the patient and saying here are the things I want you to look at and go over, and it’s personalized based on their profile,” said Krist. The design and functionality are modeled after healthfinder.gov and it is tailored to meet patient preferences and to integrate into the typical workflow of primary care.

Referring to the first two presentations in this session, Krist reiterated the importance of getting stakeholder input during the design process. “Throughout the whole process we have patient and clinician advisory boards that are influencing our design iteratively. We have had hundreds of practiced learning collaboratives where clinicians are talking about how they want to use this information, what’s important for their patients, and how they want to integrate it into the workflow,” he explained. “We have

SOURCE: Krist presentation, March 24, 2015.

diaries where clinicians, nurses, and other staff can enter their experiences with how this is going. We do usability testing, and then we have open comments for patients using the system to give us feedback whenever they like.”

Krist and his collaborators have conducted randomized, controlled clinical trials to test whether tailored information improves the delivery of recommended preventive services. They have also been able to study whether primary care practices can implement and use this portal and get their patients to use it. A recent grant from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) is enabling them to look at the decision-making journey by trying to obtain patient information before they need to make cancer screening decisions and seeing how that influences care. With a National Cancer Institute (NCI) grant, they are going to disseminate the MyPreventiveCare portal to 300 practices, many of them with low-literacy patients, in places such as inner city Richmond, Virginia, and among Native American and Hispanic populations in New Mexico.

So far, some 70,000 patients in 14 practices using 3 different EHRs have used MyPreventiveCare, and Krist noted that the number of patients is significant because it represents about 60 percent of patients in those practices. Between 50 and 100 new users sign up each week, he added. Krist said his team have had some trouble integrating into some commercial portals and that some practices are fielding two sites, their normal portal for emailing patients and disseminating lab results, and this one for preventive care. In those practices, about one-third of the patients use the normal portal, while two-thirds use MyPreventiveCare, reflecting the information needs of those patients. Across these practices, MyPreventiveCare accesses 22.9 million patient variables, and accounts for 176,742 unique EHR values and 4,941 prevention values.

In terms of what they have learned from the randomized controlled trial (Krist et al., 2014), the most important lesson has been that giving patients specific, tailored information helps them to act on preventive care. “They were more likely to go and get recommended care including screening and immunizations, and we saw increases of 12 to 16 percent for breast and colon cancer screening,” said Krist. In some practices, breast cancer screening rates were already high, yet this type of information increased those rates to what may be a ceiling, which Krist called encouraging. Another finding was that not only is it important to get patients onboard, but getting clinicians onboard had a synergistic effect. “Half of the increase was probably from patient activation and the other half was from clinician activation,” explained Krist. He added that patient summaries were sent to clinicians, leading practices to update 59 percent of patients’ medical records and contact 84 percent of patients for further

action, such as scheduling wellness or chronic care visits, or arranging for specific services.

This study also showed that patient need is substantial. In primary care settings, for example, users were up to date with only 53 percent of preventive care services. Only 2.2 percent of users were up to date on all services. On average, users who were not up to date needed 4.6 services, and in a separate study, using a health risk assessment plus tool, Krist and his collaborators found that patients on average had 5.8 unhealthy behaviors or mental health risks of the 13 items that they assessed. He noted that the practices that are using MyPreventiveCare today serve mostly higher-literacy populations, and despite being told by grant reviewers that this approach would only work with young healthy individuals who are technologically savvy, Krist and his team have found that a wide range of patients are willing to engage online. “Our highest user group was ages 55 to 65 and our second highest group was ages 65 to 75,” said Krist. “Our lowest was the 20- to 40-year-old user group.” Chronic disease, he said, appears to drive the highest level of use.

One of the challenges he and his colleagues encountered was getting information to patients at the right time, so the research team tried to engage people by sending them alerts before visits to have them review information and prepare themselves to be partners in making decisions about cancer screening, for example. This worked to some extent, but Krist said that further work is needed in the area of culture change to better integrate this process into the normal workflow. Another challenge has been to personalize content, and part of the PCORI-funded study involves asking patients who get breast, prostate, and colon cancer screening to think about and identify the information that they find most important. Focus groups with 100 patients identified the topics that were important, and fielding the content in MyPreventiveCare showed that most patients want that information in written form rather than as numbers, pictures, or stories. “I always hear that stories are great for conveying messages, but we’re finding a lot of our patients want words,” said Krist. “We’re going to be looking at this and seeing what information people access and try to think of new ways of presenting this information.” He concluded his comments by noting that there is some theory that suggests that if they do this right, this type of patient portal could reduce some health disparities, but that is something that remains to be tested and demonstrated.

REACTIONS TO THE PANEL PRESENTATIONS4

As a preface to his remarks, Dean Hovey explained that when he joined Digifit 4 years ago, the company’s focus was on developing a device and app for heart rate monitoring that individuals could use to track their fitness and improve their performance. That, however, was not what Hovey wanted to do, so he changed the company’s direction to one that developed health and wellness products that would help people learn health habits. His early background, he noted, was in product design and so he appreciated the importance of user experience. The dilemma he faced, though, is that making money in the mobile app arena is difficult because of the need to get millions of users to download the app for free and then convert some small subset of that population into customers who will pay for a premium service. “I actually wanted to get out of that business because it’s really hard to make money giving away free apps.”

The company began looking at human behavior and specifically at pregnancy because it represents a niche in which the users are young, technologically savvy, and social. Moreover, the users are hungry for information along a timeline that is predictable with the progress of their pregnancy. The challenge was to create an interactive design that will keep a user engaged for the 9 months of pregnancy to help her make good decisions. Pregnancy, as is the case with many chronic diseases, is something that tends to motivate people to take action and seek information.

The solution that Digifit created is a platform that enables them to create what they call an experienced design, which allows them to identify the target audience and the desired outcome and then develop a story arc that keeps them involved with the app. This process involves bringing together experts in the domain of interest with potential users, going into the homes of the audience that the app is intended to influence, and understanding the kind of information they need, what they need to pay attention to, and who the members of their social network are. They then put these pieces together to create a successful story arc. The Digifit platform also enables the developers to track what users are doing or not doing, which then allows them to engage in an iterative design process.

What he has learned from this process is that not only is it important to consider the needs of the individual, but of the care team involved with that individual. “You have to create social technical change with the care providers,” said Hovey. “Most providers have never been in a place where they had 24/7 data and have been able to get into a person’s home, so I

_______________

4 This section is based on the comments of Dean Hovey, an experienced entrepreneur and currently president and chief executive officer of Digifit; Catina O’Leary, president and chief executive officer of Health Literacy Missouri; and Lana Moriarty, director of the ONC’s Office of Consumer eHealth.

think that’s the big piece here: How do you dive deep and interact and then make that information available?”

Catina O’Leary, who explained that she was representing the nonprofit sector, said her reaction to the three presentations was to wonder how her small company doing nonprofit work can engage at the intersection of companies and people. She noted that Health Literacy Missouri’s offices are in a start-up incubator in St. Louis called T-Rex. When she tries to explain to the other companies working there what she and her colleagues do, they seem perplexed and cannot figure out how that fits and what a partnership would be like. “Figuring out what those relationships look like and how we can inform and participate is important,” she said.

To some degree, it is great to hear people talk about going into homes and doing this work, said O’Leary, but her experience doing community-engaged research has been that the people who need the most help are reluctant to let researchers into their homes. “So how do we then also speak for the most vulnerable in our communities when that’s appropriate, and what do those links look like? That’s one of my most relevant reactions,” O’Leary said.

Her other major comment, based on the work that her organization is doing, is that what people are really struggling with these days is figuring out the new health insurance laws and the benefits they are entitled to now that they have insurance. She told a story of a recent encounter she had with the health system, a first-time visit to the emergency room with her 6-year-old. She had called the phone nurse on a Sunday and was told based on her child’s symptoms to go to the emergency room rather than urgent care. The result was a $300 bill, which O’Leary said was fine and understandable, but when she thought about people who do not have the resources that she has, it made her ask a number of questions. “How do people figure out what they need to know? How do they show up with the resources that they need? Where’s the technology piece for that?” she asked.

She noted that one thing she and her colleagues have been hearing in Missouri is that people are using the periods outside of open enrollment to understand their health insurance and they are going back to the navigator who enrolled them to ask direct questions. The navigators often do not have answers and do not even have the information needed to answer those questions anymore. “I think we need to be talking about who these apps are for,” said O’Leary, adding that while there is a need for consumer apps, there is also a need for apps for the providers, many of whom may not be trained in areas such as ethics and privacy.

The final reactor, Lana Moriarty, said that Holman’s comment about looking to the private sector for innovations sums up the way ONC approaches much of its work in the field of health literacy. “We try to find the best practices, try to bring those to the table, make sure the right people

are at the table,” said Moriarty. She recounted her time working for the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) in the field with underserved populations and remarked that it is important when thinking about digital health literacy to recognize that a significant proportion of the U.S. population struggles with computer literacy. She noted, too, that her team from ONC had a recent conversation with a provider in Tennessee who was meeting the meaningful use criteria, but whose major issue was that most of that practice’s patients did not have computers and had no idea what computer to buy. In addition, while patients may have had smartphones, they may not have been downloading apps. “We need to consider that perspective,” she said.

She commented how she was thrilled that the three speakers looked at how consumers and patients are really using technology, identifying the type of information they need, and then designing their apps and websites accordingly. “I appreciate the fact that this is about a user-centered experience and user-centered design,” said Moriarty. “That is a key point.” She reiterated the point that Holman made regarding the need to have intelligently structured data, without which there is the risk of having people misinterpret information and perhaps act on misinformation. “It is so hard to navigate across disparate sources of information,” she said.

Moriarty said she was happy to see healthfinder.gov taken to a new level with MyPreventiveCare and was impressed with how many patients are using that portal. She said she wanted to explore with Krist issues of scalability and replicability, particularly because it appears that this portal breaks down some of the silos that have developed in the nation’s health care system. “I know it wasn’t the government’s intention to create 10 different portals for your primary care physician and your different specialists, but that is the reality that we are living in now,” she said. In fact, her team has been looking at an architecture that wraps data around a person instead of having it spread across disparate places, so she is eager to talk more about how to make that happen.

To start the discussion session, Suzanne Bakken asked the panelists and reactors if they had ideas on how to create a story arc for the use of consumer-facing technologies that takes health literacy into consideration, and if so, what some of the key targets for that story should be. O’Leary responded that the answer to this question relates to her comment that partnerships are important. “There’s not one health literacy and there’s not one story to tell,” she said, which is why it is such a complex undertaking to communicate information across all kinds of conditions and accounting for all the different levels of understanding, from the patient to the physi-

cian and the health care organization. One challenge lies in the fact that many of those developing apps have never heard the term “health literacy” and have no idea of how to develop an app that has a foundation in health literacy. “So how do we make what we’re doing become more central to the conversation, because it’s not right now?” asked O’Leary. “We’re still an emerging discipline, as much as we hate to admit that. So with that, are we really surprised that app creators don’t know how to include this? Of course they don’t.”

That reality, in fact, is why Hovey’s company has created a tool for app development given that app developers in general are not the subject matter experts. What needs to be done, said Hovey, is to give app developers the ability to merge their expertise with the experience of the health experts. As an example, he noted how an experienced heart surgeon has had conversations with hundreds of patients about what surgery and postsurgical recovery will entail. That surgeon understands that the conversation with each patient and the patient’s family will be different based on what each patient hopes to gain from having surgery. This need to personify the message based on who the target is and what each individual’s experience will be as far as what kind of information they get from an app does create a challenge. The surgeon may not have time to personalize that experience, but a nurse practitioner could help a patient download an app, provide instruction on how to use it, and set it up in a way that meets the needs of that specific patient.

Rosof asked how the health care team is going to find the time to educate patients about the use of technology, and Krist replied that there is, in fact, not enough time. The goal, though, is to integrate technology into the care setting so that it produces a net time savings. For example, his group has been trying to use the content that is coming from the patient experience to create standing orders for practices that will save time. In some cases, he said, these standing orders enable practices to use their secretarial and medical records staffs to call patients and offer them preventive services. “We’ve been trying to shift who is doing activities within practices as part of our strategy,” said Krist, who added that he believes “there are many untapped opportunities where promoting health literacy, building teams, sharing information, and creating partnerships can really change what we can do.”

Wendy Nickel, director of the ACP’s Center for Patient Partnership in Healthcare, commented that 30 percent of ACP members are still in solo practice even with the move toward patient-centered medical homes and care teams. “These practitioners who are in solo practice don’t have the time to sit down with their patient and go through their apps.”

Hovey added that smartphones may not be the answer for all patients—the means to deliver this technology could be television and a remote con-

trol—and the key to success will be to deliver the technology and experience based on the needs of individual patients. Moriarty agreed with this last comment and with the idea that it is not likely to be the doctor who is teaching the patient how to download an app or use a particular technology tool. She added that her team has been studying how patients contribute to and manage their health care, what their goals are, and how they account for those life goals. If the whole point of being healthy is for a person to be able to do what he or she wants for as long as possible, asked Moriarty, at what point is it possible to create a story arc that enables an individual to use one of these technologies to help plan what to do to meet that goal and to become a partner with the entire care team?

Krist noted that patient stories are important for providing an understanding of the patient’s perspective, and one of the things he has learned from his team’s work is the importance of getting a breadth and depth of input. “In many of our studies, we have patients that we really partner with and they function with us as co-investigators and co-developers,” said Krist. “We get really intensive input from them.” He added that it has been important to see how these patients’ stories change over time as they experience the health care system, and he also noted the importance of generating the evidence that a particular kind of input is beneficial. “The doctor in me quivers at 24 hours of patient data, and on the one hand I want it, but on the other hand, I want it only if I can act on it and it’s going to improve things for my patients and make them better,” he explained. In the same vein, the idea of having informaticians in his office mining these data is fine as long as the cost is balanced by how useful it is to have that kind of intense data analysis at hand. “I believe a lot of this is helpful, but I also believe it’s our job to prove it’s helpful before we advocate for it on big scales,” said Krist.

Schnall commented on Holman’s observation about how consumers rely on the Internet for their health information and noted that participants in her team’s research have said they find answers to health-related questions from a doctor on Yahoo Answers. Part of the health literacy challenge, then, is to move past the idea that the prettier the website, the better the information must be. A shortage of information is not the problem, but helping people who can freely access information via their smartphones or computers to understand that information is a major challenge. To put that challenge in context, Holman said there are more than 40,000 Google searches per second, with 1 of every 20 of those searches health related, and while Google is the dominant player in the search field, it only accounts for about 58 percent of all searches.

Holman then remarked that he has a problem with the phrase “health literacy” because it implies to him that the problem is with the user. In his mind, the challenge is not to teach the public how to understand health messages, but to make health messages understandable from the start. As

an example, he said that nobody talks about energy literacy, but the energy field has made a great deal of effort, led by the private sector, to educate people about their energy usage. Well-designed technology can help when it conveys useful information in such a way that users do not even realize they are engaging in a learning experience. In such cases, the usage experience is so intuitive that it becomes routine and natural enough to then have an impact on behavior.

Ruth Parker, professor of medicine, pediatrics, and public health at the Emory University School of Medicine, asked the panelists to describe what the public needs to understand today about privacy, data, and electronic health information. Hovey said it would be helpful if the people who wrote the explanations in the privacy notices of how data are going to be used did so in a simple format that says, “We’re going to do this, this, and this, and we’re not going to do this, this, and this,” he said. The Apple research kits, he said, have done a good job of doing just that.

Social networking and crowdsourcing and how they enable patients and end users to share information can be powerful tools, said Schnall, but at the same time it is necessary to consider privacy and security. A challenge for the roundtable, she said, is to think about how to use those kinds of tools as a source of information and as a means of providing information through venues such as support groups for patients living with or at risk of disease while maintaining privacy and data security. Hovey cited pregnancy as an example of where the privacy issue is important and changing. During the first trimester, pregnancy is a secret, but as the pregnancy progresses the circle of who is in the know grows ever larger. “You have to be aware of that and you have to be aware of the spouse, the friend, the community advisor, the doctor, the nurse practitioner, and with each of those you need to have a unique view into the world of the patient,” said Hovey.

Moriarty said she would be remiss if she did not mention the Blue Button connector website (bluebuttonconnector.healthit.gov), which was created as a one-stop shop for consumers to understand their legal rights to their electronic health information and to better prepare themselves for conversations on the topic with their health care team. The site was launched in September 2014 and already has 600 members who have committed to open data and giving consumers access to their data. It is also a place where consumers can find out about different apps that are on the market and how to aggregate and manage their health information. Bakken explained that there would be more time to discuss privacy and data access during one of the afternoon sessions of this workshop.

Michael Paasche-Orlow commented that intuitive design is in the eye of the beholder. He recounted a story of trying to get his 80-year-old father, who went to Harvard Law School and still practices law, to use his smartphone to take a picture of his mother, whose face was swollen after surgery.

“My head almost exploded in the process of trying to get him to do this,” said Paasche-Orlow, “so intuitive design may be intuitive to you, but you actually have to find your target audience, understand what they can do, and figure it out.”

Turning to the subject at hand, Paasche-Orlow said that although it is important to focus on knowledge and information exchange, people are not going to use an app unless it makes their life better, and so the main issue is function—what an app can do for an individual. “Can I make it so that I don’t have to go to the pharmacy 10 times this month and instead synchronize all my medications to get picked up on the same day? That would make my life better,” he said as an example of something a useful app could accomplish. Technology, he said, needs to reflect the fact that health care is a service industry, and that if all a technology does is transfer knowledge, it will not gain long-term use. Schnall added that it is not just a question of whether an app makes a person’s life better, but if it is designed in a way that is entertaining, interesting, and compelling. She cited the fact that people waste hours playing games on their smartphones despite the fact that doing so does not make their lives better. “It’s thinking about the functionality that our end users need that will help them continue using an app,” she said.

For Krist, functionality is about making life easier. For example, an app that can better prepare a patient for a doctor’s appointment and make the encounter a better use of time would be one that would make life easier. One thing that he has seen is that people get invitations to enter information into a portal to share with their doctor, but that they do not do so until after the visit, suggesting that perhaps the visit is a place where the physician can reinforce how much that information would have been useful to have beforehand. In that regard, he wondered if having thousands of apps in the market is a good thing because different approaches work for different people.

Rosof asked if the story arc can create cultural change by putting technology into play. Hovey said that can certainly help, but that smartphones and computers are not going to work with everyone. Today, he noted, a significant percentage of the population that most needs health information grew up in an era of radio and analog technology, and that group of people is likely to be more comfortable with a different type of user interface. One approach might be to change the reimbursement system to encourage health systems to deploy remote technology that would be useful to an elderly population instead of building new buildings. Until the health care enterprise starts thinking about software investments, which is about people and experiences, it will struggle with getting useful information to the population that needs that information the most today.

Terry Davis, professor of medicine and pediatrics at the Louisiana

State University Health Sciences Center, asked Hovey if he could teach the workshop something about what makes icons intuitive given that icons are important in health literacy. Hovey replied that it is important to remember that “you don’t need an icon for everything,” and he cited Apple’s use of a button that says “next” instead of trying to come up with an icon that conveyed the same idea. “Sometimes we icon everything and it’s not always easy to create an icon that communicates across the board,” said Hovey. One of the features built into Digifit’s system is that it records everything the user taps on their smartphone so that the developers can know if they used a particular feature and used it correctly. This capability, which is enabled by the Google App Engine and the company’s ability to query large amounts of data, is showing that sometimes words work well and sometimes words plus an icon works better. He also noted that words may be needed only during the initial learning phase for an app.

Holman noted that jargon is often a middle layer between icon and plain language, and that there is often a period when a concept is introduced that requires simplicity. He explained that consumer brands deal with this problem regularly. He reminded the workshop that the Starbucks logo has undergone changes over time to reflect the fact that they needed to first introduce the lady on the logo and get people to associate that the lady equals Starbucks. “There’s a mental translation between icon or brand and plain language, and I think where we the experts get stuck is in that middle layer, where we try to use words, but we’re actually using jargon. It’s a shortcut for us to mean something that through more words could actually be in plain language,” said Holman.

Adriana Arcia, assistant professor at the Columbia University School of Nursing, said that she has been working with Bakken to develop infographics that can help a largely Dominican immigrant population with low health literacy understand patient-reported outcomes (Arcia et al., 2015). This has been an iterative process involving an interactive, participatory design exercise with the community, and the results have been surprising, she said. “We developed all kinds of different graphics using icons, and they were largely unsuccessful, especially anything that used repeated icons to represent multiple instances of any particular thing, such as servings of fruit,” said Arcia. What did work, she said, is stars because games have taught people to rate things on a five-star system. “If the icons are really ubiquitous, if we’ve been trained to use them, then they’re going to be successful.”

Arcia then asked the panelists if they had any examples of assumptions that did not pan out. Holman replied that his office at one time ran competitions with cash prizes to spur the development of health-related apps. The competitions did accomplish that, but the surprising finding was that the developers were not taking the apps to market; they were just taking the cash prizes and going off and doing other things. “So it’s a struggle in

the world of open innovation to build sustainability into business models, and we’re still trying to figure that out,” said Holman.

Laurie Francis, senior director of clinical operations and quality at the Oregon Primary Care Association, reminded the workshop that the emphasis on training needs to be on the entire clinical team, not just the physician, and that the end user is actually the consumer, not the clinical team. She then asked about the relationship between the profit motive and the private sector and the fact that the people who most need this kind of help often do not have the money to pay for apps and the like. “Capitalism isn’t looking for the consumer who has no money,” she said, wondering how to create products for those who are most predisposed to poor health. Hovey responded with an example. Digifit is working with a group that provides in-home and clinic-based dialysis, and many of its clients are low-income individuals who cost the government some $60,000 per year just for dialysis. If Digifit can design an app that allows more of these individuals to receive less expensive in-home care and involve family members to provide part of the care, there may be an opportunity for the company to carve out some of the resulting savings.

Laurie Myers, lead for health care disparities and health literacy strategy at Merck, asked if the change in payment models that is occurring is creating opportunities to finance the need to put these technologies into the hands of those who need them most. Holman agreed that the shifting payment system is creating massive opportunities from a strictly capitalistic business perspective, particularly when juxtaposed with the incredible pace of technological change and the rate at which technology continues to become less expensive over time. He noted that Apple’s deliberate decision to position itself at the high end of the market is a reflection of the fact that technology is going to get cheaper and that the market for these products will grow as a result.

Myers noted that she has been struck with the obligation of the field to think differently about the system and reduce complexity in a way that will enable disparate populations to take advantage of these technologies. Along those lines, she wondered if there are lessons from the gaming sector that might provide some insights into how to make these apps more universally attractive to end users. Hovey replied that one important lesson from the gaming industry is that many of the games are modular. “When they decide to add a new feature they snap it in and give it a 2- or 3-day test run, and if people use it, it stays in the game and if not, they remove it,” he explained. Holman said that games are wholly immersive and that making information available through that sort of immersive experience is important.

Moriarty noted what an exciting time this is from her perspective given how many different factors are coming together, particularly with regard

to the increasing number of consumers who are using portals to access their health information and the changing reimbursement structure that will increase data sharing across health care systems. “If we’re going to get interoperability, we need more end users in the system and more people demanding for it to change,” she said. Interoperability, she explained, is really about the ability to have data when and where the consumer needs it. The more consumers ask for their data and the more they demand that all the members of their health care team have access to their data, the more pressure will be brought to bear to make interoperability the norm.

Krist added that changing reimbursement policies are creating an opportunity for technology to help shift the cost curve as accountable care organizations take root and the demand for care coordinators, case managers, and patient navigators, many of whom have health literacy issues themselves, grows. Myers agreed and said that technology aimed at these new members of the health care team can help address these health literacy issues.

Nickel asked if the health care technology industry was going to help clinicians find the appropriate apps, out of the 40,000 or more available, that will support shared decision making between clinicians and their patients. Schnall noted that she and a colleague recently completed a review and analysis of existing mobile phone applications for health care–associated infection prevention (Schnall and Iribarren, 2015) and found there were 19 apps available. Of these, 18 provide only information, which she said is no different from picking up a book and reading the current guidelines on health care–associated infections. Only one of the apps provided feedback. She said that while she has not reviewed all 40,000 apps, she guessed that there is not a great deal of depth and richness in the health-related apps that are available. “We know that technology can be an enabler for helping people change their behaviors, but we’re not developing technology that is an enabler for changing behaviors,” said Schnall. This will only happen, she said, by going back to the drawing board and including end users and the entire care team in designing technology that can actually help people help themselves. Bakken noted that this topic would be discussed further in an afternoon session.

Wilma Alvarado-Little, principal and founder of Alvarado-Little Consulting, asked the panelists and reactors if they have any ideas about how to bridge the difference between someone being overwhelmed by the complexity of an app and noncompliance. Moriarty said she has been talking with health care providers who have told her there is a need to look at individuals who are given the opportunity to access their health data electronically, but do not take advantage of that opportunity. “Are we saying they’re not interested? Are we saying there’s no consumer demand for the information? Are we artificially suppressing demand by some of our work-

flow or by the cumbersome ways in which they may be accessing those data?” asked Moriarty. Answering those questions is important, she said, because it is the only way to fully understand what consumers want and how they can best access it according to their capabilities and needs, not those of the app developers.

Krist added that his group has some data showing that doctors may not think that their patients will use a technology at first, but then something happens, a few patients start using the portal or an app. Suddenly the doctor realizes that his or her patients will use the system and there is an avalanche of use. The challenge there is that patients ultimately get to decide whether they use technology or not. Doctors cannot be gatekeepers preventing use and if patients chose not to use technology then practices may suffer on some performance measures.

Erin Kent, program director in the Outcomes Research Branch of the Healthcare Delivery Research Program at NCI, noted that recent research (LeBlanc et al., 2014) found that having technology in the examination room can either improve a patient–provider encounter if the provider’s baseline communication quality is already high, or it can actually hinder the social connection and communication that goes back and forth between the patient and provider if it is low. She also noted that studies of automated symptom reporting systems found that it is critical for patients to have access to a live human being on the other end of the phone and not just a recording. In that context, she asked if the panelists and reactors were thinking about how technology can be used to activate the human social component that patients need to change behavior. Holman responded that this is probably the right question to wrap up this discussion because one of the fundamental tenets of interacting with customers is talking to them, being able to have meaningful conversations, and being able to communicate in a way that works for them. “That’s true whether you’re talking about building an app or talking about teen pregnancy prevention,” said Holman. He noted, though, that the technology space is not aiming at getting humans to interact with each other, but at understanding how to build the human components and the personification of human qualities into technology as a means of engendering trust that the information being delivered is useful and meaningful.

Moriarty commented that she has been seeing a growing number of hospitals and provider networks that are developing innovative ways of integrating social data into their EHRs with the goal of being able to show a patient in a limited amount of time that they care about them as a person. As examples, she cited the Chicago-based organizations that are making a database of community resources available to physicians so that they can put their clients who may have just lost a job or have to find a new place to live in touch with resources that can help them, and a physi-

cian in Washington, DC, who is connecting his low-income and migrant populations to parks near their homes so that they can get their families engaged in health-promoting activities. “Those are examples of how we’re using technology to bring the human element into the exam room and the clinical setting,” said Moriarty.

Hovey said his dream is to outfit a physician with a tablet that can provide distilled information on what the patient has done since last being seen to determine if the patient followed through on any recommended actions. Such an app would enable the physician to then focus on the items that still needed action. He then told a story about his recent encounter with a retinal surgeon, who he had gone to see because he had a retinal tear that needed repair. The surgeon sat down at his computer and had his back to Hovey, so Hovey decided to engage him and started asking him questions. The result was that the two of them engaged in a conversation on things that Hovey found important, but this episode illustrates the point that most doctors need training when they are also using a computer in the examination room, on how to engage their patients in a way that is most meaningful.

In closing the discussion, Rosof said that what he heard is that one of the most valuable attributes in the doctor–patient relationship or the health care team–patient relationship is trust. “So the question is, how can technology build trust? We have to think about that because we can’t lose the trust piece, which is probably part of the time piece,” said Rosof.

This page intentionally left blank.