1

Building the Health Workforce

Key Messages Identified by Individual Speakers and Participants

- Despite constitutional guarantees of health care in Brazil, there is no way that the government can assist everyone in tertiary and highly complex systems. The only solution is to strengthen a primary health care system, which can address 80 percent of the health care demand. (Campos)

- Despite the high quality of care, the amount of money being made downstream in all the procedures, all the emergency room visits, and all of the surgeries and hospitalizations cannot make up for the fact that for 20, 30, and even 40 years, Native Americans have suffered from the worst educational outcome, the poorest access to nutrition, social marginalization, racism, and many other causes that make up the social determinants and underlie why people are ill. (Kaufman)

HEALTH WORKFORCE ISSUES, HEALTH PROFESSIONAL

EDUCATION, AND TECHNOLOGY

Francisco Eduardo de Campos, M.D., Ph.D., Ms.C.

Open University of National Health System of Brazil

Professor Francisco Eduardo de Campos is a public health specialist and physician who was the Minister of Health’s Secretary of Human

Resources following the democratization of Brazil. In that position, he led the proposal for unification of the Brazilian health system and coordinated the human resources group in the National Commission of Health Reform. From 2005 to 2010, Campos was secretary of management of education and the workforce for health and is currently the executive secretary of the Open University of the National Health Systems.

Campos began his keynote address by describing some of the changes affecting the health workforce. There is an aging population and there are proposals for universal health coverage; there are also calls for greater attention to the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases by the United Nations General Assembly while the number of major epidemic outbreaks appears to be growing. These changes and calls for change are intensifying the quantitative and qualitative scarcity of health workers in the world. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates the current workforce deficit to be at 7.2 million, but by 2035, that number is expected to rise to almost 13 million (WHO and GHWA Secretariat, 2013).

With the increasing desire and need for greater care to more people, Campos questioned how this would be paid for. For example, on average Brazil spends 10 percent of what the United States spends on health care. However, in breaking it down, the top 2 percent of Brazil’s population spends as much as someone in the United States, leaving few resources for the rest of the population. The new Brazilian constitution contains four articles stating that health is a right in the country and a duty of the state. The government is now struggling to determine how to make this vision a reality.

Roughly 70 percent of the Brazilian population depends exclusively on the national health system, while about 30 percent are on private plans. As more people move from poor to middle class, they desire private insurance, although the National Health System in Brazil covers 100 percent of the costs of vaccines, emergency care, epidemiologic surveillance, and the like because it is in the constitution. Paradoxically, Brazil leads the world in publically funded organ transplantations and is second only to the United States in the number of these highly complex procedures that are performed yearly. The situation is similar for expensive medications that fall within the national health system liability and have led to litigations linked to the constitutional guarantee. But despite these constitutional guarantees to health care, there is no way that the government can assist everyone in tertiary and highly complex systems. The only solution, said Campos, is to strengthen a primary health care system, which can address 80 percent of the health care demand.

Currently in Brazil there are about 44,000 family health teams spread around the country covering roughly 65 percent of the population. Cou-

pling this with the 30 percent who have private insurance, Campos believes that everyone is covered by the health system in Brazil.

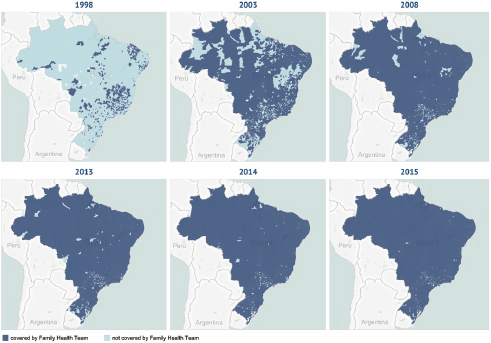

Family health teams are composed of a physician, nurses, dentists, and community health workers (CHWs). Most teams employ six CHWs who are recruited locally by the municipalities. The system is quite decentralized in Brazil and is run by the municipalities that hire local workers to provide primary health care to populations in specific geographic districts that are assigned to them. Figure 1-1 shows the progress between 1998 and 2014 of providing family health teams to the population. The light grey points are municipalities without a primary health care team, and the dark grey points are the municipalities with family health teams.

This rise in the number of family health teams demonstrates Brazil’s political commitment to primary health care. It is seen as a pathway that must be integrated with the entire network. There is a strong referral system at secondary hospitals, community hospitals, and tertiary hospitals that, in general, are the university hospitals in Brazil. While the system is in place, Campos said the challenge for the Brazilian leadership is human resources. Having a properly trained and motivated professional team that is willing

FIGURE 1-1 Timeline of family health teams deployment in Brazil, 1998 to 2015. SOURCE: Department of Primary Care, Brazilian Ministry of Health (MOH), 2015, as presented by Campos on April 23, 2015.

to work in rural and remote villages was traditionally the main constraint of the strategy. However, talks with the Ministry of Health are aimed at reversing the situation. Some of the proposed policies would include expanding enrollments, changing curricula, improving employment, offering eHealth, providing continuous education, and hiring foreigners. For example, Brazil currently has 13,000 Cuban doctors. Though this is a major controversy, it was the Cuban workers who enabled Brazil to increase the number of teams from 33,000 to around 40,000.

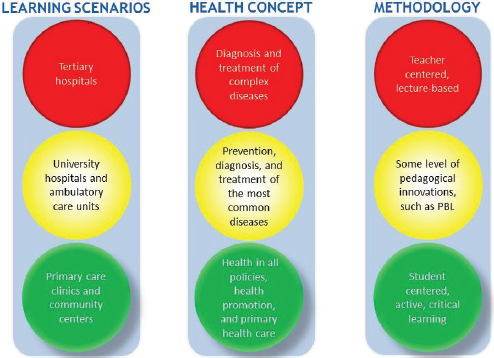

Campos selected “changing curricula” and “continuous education” to describe in greater detail. Brazil used to have a conservative and traditional medical and professional education. As seen in Figure 1-2, this program is set up to consider three axes. The first axis is learning scenarios, the second is health concept, and the third is methodology. The first row is in red to metaphorically indicate what education should not be; it should not be centered on tertiary hospitals, be based on diagnosis and treatment, or be founded on teacher-centered lectures.

FIGURE 1-2 Three axes of a metaphorical approach to health professional education in Brazil.

NOTE: PBL = problem-based learning.

SOURCE: Campos, 2015.

The yellow circles contain learning scenarios that can be brought in for the most common diseases and taught using somewhat innovative pedagogy. The green circles in the bottom row are what education is striving to be. This includes a focus on primary health clinics and community health centers, health policies that address the social determinants of health, and education that is student centered, active, clinical, and emphasizes critical thinking.

Ideally for Brazil, the red and yellow circles will be replaced by the green circles. To facilitate the shift, the Ministry of Health provided funding to all the schools in Brazil interested in changing their curricula. For example, funding could be sought by primary health care centers to obtain meeting space, upgrade facilities, or set up an Internet connection. At the end of his term, Campos reported that 365 colleges applied for resources from Ministry of Health to change their curricula.

Campos then discussed continuous education and an initiative he is responsible for in Brazil. The Open University of the National Health System has been set up by the federal government to offer continuous education. It is a consortium of public universities, based at Fundação Oswaldo Cruz (FIOCRUZ). It has the largest repository of open educational resources in Latin America and retains records of all health workers and their registered achievements. Open University was set up by the federal government through a presidential decree. It is a government-sponsored, interfederative and collaborative network of public universities in Brazil willing to participate in a program that goes beyond traditional graduate studies. There used to be scarce public support for continuous education in Brazil. As a result, much of the education is conducted by pharmaceutical companies, which according to one local newspaper, has become the main source of continuous education for doctors and a potential conflict of interest for them.

Currently the top-ranking federal universities of Brazil are participating in the program of continuing education of health professionals. There are roughly 2,000 educational tools and materials uploaded onto their platform that are accessible free of charge to everyone anywhere in the world. This is different than a massive open online course (MOOC). Examples of available courses offered at the university are

- Specialization in primary health care/family health (20,000)

- Other specializations: environmental health, mother and infant, aging

- Updates in home care

- Self-learning certified modules: dengue, influenza, chikungunya, malaria

- Equity issues: lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people; indigenous; African descendants; and others

They range from soft to strict certifications, online to offline opportunities, and profession-centered to more general courses. The total enrollment is close to 200,000 health professionals who can run the program on their mobile devices to maximize their educational time.

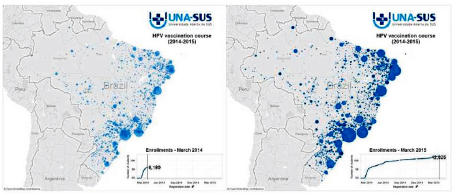

Campos described one course in more detail to demonstrate how the Open University is connecting to Ministry of Health policies. Six months ago, Brazil’s Ministry of Health made the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination available to all girls free of charge. The minister asked health workers if they planned to make the vaccine available in their facilities, and they said doing so would require training of physicians and nurses on how to administer the vaccine. Open University responded by providing an online HPV vaccination course that grew in popularity with the rollout of the vaccine, and reached almost 13,000 health workers (see Figure 1-3). Some of those accessing the course worked in remote parts of the country that in the past would have needed several hours of flying time to reach a location where the course was offered.

In closing, Campos reiterated that well-educated, motivated, managed health workers are at the core of the health system, and for Brazil, primary health care is the pathway to universal access. But that is not where it ends. Primary health care must be networked with hospitals, with psychiatric care, and with dentists to fully function, and it must also be connected to all of the other networks in Brazil, said Campos. In addition, continuous education must be free from conflicts of interest and accessible to all in order to improve the availability and the quality of the health services, he said.

FIGURE 1-3 HPV vaccination course.

NOTE: HPV = human papillomavirus.

SOURCE: Campos, 2015.

SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH:

CHANGING THE CARE TEAM

Arthur Kaufman, M.D.

University of New Mexico

The Vice Chancellor for Community Health at the University of New Mexico, Arthur Kaufman, spoke about social determinants of health and changes his university is making to health teams. He illustrated his points through two examples. One drew upon ideas from the agriculture sector and the work of farmers, while the other took the lessons learned from Brazil’s work with community health workers.

To set the stage, Kaufman asked the audience to consider a single health indicator—death from diabetes. Native Americans, who make up roughly 10 percent of New Mexico’s population, have the highest mortality rates from diabetes despite having access to the best screening and treatment for diabetes (New Mexico Department of Health, 2010). One may ask how a population could have the best quality of care with the worst outcomes? The reason, said Kaufman, is that despite the high-quality care, the amount of money being made downstream in all the procedures, all the emergency room visits, and all of the surgeries and hospitalizations cannot make up for the fact that for 20, 30, and even 40 years, they have suffered from the worst educational outcome, the poorest access to nutrition, social marginalization, racism, and many other causes that make up the social determinants and underlie why people are ill. Social determinants include income, education, nutrition, housing, transportation, safety, social inclusion, and built environment. Despite our health system spending massive amounts of money on health care, Kaufman said that this system only accounts for 10 percent of reducing premature death (Schroeder, 2007). Kaufman raised the question of how to reallocate the 18–20 percent of the gross domestic product currently spent on health care toward upstream resources that actually improve health. As long as the current incentive system remains in place, he said, evidence produced that demonstrates the value of such a redirection of health service funds toward addressing social determinants will have little impact.

With a recognition of the financial and societal effects of the social determinants of health, the University of New Mexico embarked on creating a new vision:

The University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center will work with community partners to help New Mexico make more progress in health and health equity than any other state by 2020. (UNM, 2015)

This vison based success on how well “health” was achieved in the state. Kaufman acknowledged this was a risky proposition with fears the vision would not be achieved, but the institution moved forward regardless. As part of the plan, he and his colleagues adopted the 3/9/27 rule of effective public health messaging whereby communications like the vision statement would contain no more than 3 concepts, expressed within 9 seconds, in no more than 27 words. To translate the vision into action, Kaufman’s group first traveled around the state gathering opinions from New Mexican citizens about the role of the university’s health science center for improving citizens’ health. It came as a surprise to learn that many were dissatisfied with the institution’s performance. Main complaints included priority setting from the university’s perspective instead of that of the community. Interest in the community by the university was often trigged by a grant with the disappearance of the university from the community when the grant ended, demonstrating little long-term commitment to the community. Citizens also said the university did not compare well to the state’s agricultural college, which places full-time agricultural cooperative extension agents in every county in the state.

Extension is a program that provides informal education and learning activities to people throughout the United States, provided through U.S. land-grant colleges and universities (NIFA, n.d.). It applies knowledge from research to benefit agricultural producers, small business owners, consumers, families, and young people in an effort to improve lives. They help students graduate from schools with 4-H clubs, improve the quality of farming, and make agriculture more effective. In essence, they connect with people and communities, which was the model Kaufman and his colleagues wanted to duplicate.

The decision was made to create a parallel, University of New Mexico–run “health extension” system in New Mexico. A key role of the agents is to determine priority health issues for their community and to connect individuals with the university’s health science center resources. In this way, the need drives the resources and not the other way around. For example, communities on the Navajo reservation grew tired of the constant turnover of doctors, nurses, and pharmacists. Their solution was to recruit and train locally so the health workers would be members of their community and would stay on the reservation to provide ongoing care to their neighbors. Through collaboration with the cooperative extension workers, the university’s health extension agents were able to build such a program for educating, training, and placing local health professionals. This program has been scaled up and is available across the state.

Kaufman attributes the success of the health extension program to building and using connections with such local resources as state and junior colleges, community hospitals and health centers, civic organiza-

tions, county health councils, and area health education centers. Another reason for their success is the community health agents themselves. These are frequently members of the community with a high school education but no training in health or health systems. Learning from other countries, Kaufman and his colleagues provided appropriate training to them making them part of the entire system of care. This gave agents tremendous respect by their communities that also translated into political power because agents have the ability to sway voters—a finding also expressed by Campos.

A second major development in addressing social determinants was the training and deployment of CHWs as an interface between the clinical health care system and the community. CHWs are paid by the university but are selected by their community. They are culturally and linguistically competent, live in the community they serve, are usually from underrepresented ethnic minority communities (such as Hispanic, Native American, and African American), are trusted members of the community, and have access to all the community’s and university’s resources to address local needs (Kaufman et al., 2010).

To get the program started and funded, Kaufman worked with health insurance companies who were focusing on managed care. This was now possible under the new U.S. health care law, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, because for the first time, instead of managed care focusing on containing hospital costs, it was supporting upstream prevention efforts. The shift was mainly due to changes in reimbursement incentives through “capitation” (a system of payment for a person rather than for a service). With this system, providers who keep their patients and communities healthy and out of the hospital receive more of their per person payments.

The university’s efforts to partner with health insurers created a 4:1 return on investment for the insurers through reduced emergency room use, fewer hospitalizations, and lower costs of medications. This program has now expanded to all 33 counties in New Mexico and is a model being replicated in 10 other U.S. states. But in most places across the United States, community health workers are employed to work with the top 5 percent of users of the health care system, known as the “hot spotters,” who account for more than half of the health care spending in any enrolled population. By targeting these few individuals, often using health literacy with outreach from community health workers, it is possible to decrease hospitalizations and costs for people with severe disease. While the intervention does save money, it does not address population health or the underlying causes of disease. It does not prevent patients from becoming “hot spotters.”

Kaufman and his colleagues adapted the hot spotters model to take into consideration the entire population. They are now using CHWs in a project working with 20,000 capitated Medicaid recipients in New Mexico

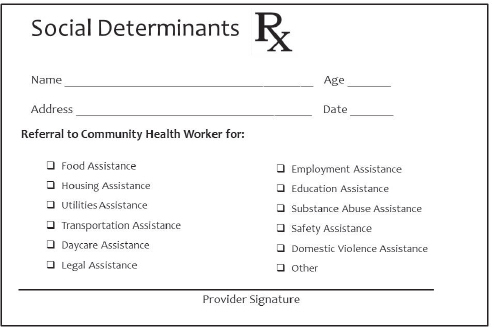

FIGURE 1-4 Social Determinants Rx.

SOURCE: Kaufman, 2015.

for chronic disease management and for prevention and wellness interventions for all enrollees. To identify risk for adverse social determinations in the general Medicaid population, Kaufman’s group developed a “social determinants prescription pad” as a screening tool that could be part of the electronic medical record (as depicted in Figure 1-4).

Using this method, the CHWs have uncovered major adverse social determinants in at least half of the population walking into their clinics and health centers. The most common social determinant is not being able to pay for utilities, followed by the need for assistance with income, education, housing, and food. What many do not realize is that there are programs to assist patients with these needs. These are the sorts of issues the CHWs can address along with all the other social determinants, as well as patient medication compliance.

Kaufman closed by going back to the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center’s vision to make significant progress in health and health equity. Using data from the United Health Foundation (2015b),1 it appears that New Mexico has improved its ranking since 2012 (see Table 1-1). The

________________

1 The database includes data on behaviors, community and environment, policy, and clinical care in order to generate reports that provide an overall sense of the nation’s health. To access the database, visit americashealthrankings.org (accessed July 6, 2015).

TABLE 1-1 U.S. Annual Health Ranking by State

| 2012 (ranking by state) | 2013 (ranking by state) | 2014 (ranking by state) |

| 30 Illinois | 30 Illinois | 30 Illinois |

| 31 Florida | 31 Delaware | 31 Texas |

| 32 Delaware | 32 New Mexico | 32 Florida |

| 33 Michigan | 33 Florida | 33 New Mexico |

| 34 North Carolina | 34 Michigan | 34 Michigan |

| 35 Texas | 35 North Carolina | 35 Delaware |

| 36 New Mexico | 36 Texas | 36 Missouri |

SOURCE: Kaufman, 2015, using data from United Health Foundation, 2015a,b.

change from 2012 to 2013 was particularly striking as New Mexico had the fourth highest jump in ranking compared to the other 49 states. And while Kaufman does not know whether his group will reach the 2020 goal set forth in their vision, he does know that the contribution of the university is making a small but significant difference in improving the lives of those negatively affected by the social determinants of health.

REFERENCES

Campos, F. 2015. Health workforce issues, health professional education, and technology. Presented at the IOM workshop: Envisioning the Future of Health Professional Education. Washington, DC, April 23.

Department of Primary Care, Brazilian MOH (Ministry of Health). 2015. Histórico de cobertura da saúde da família. http://dab.saude.gov.br/portaldab/historico_cobertura_sf.php (accessed August 20, 2015).

Kaufman, A. 2015. Social determinants of health: Changing the care team. Presented at the IOM workshop: Envisioning the Future of Health Professional Education. Washington, DC, April 23.

Kaufman, A., W. Powell, C. Alfero, M. Pacheco, H. Silverblatt, J. Anastasoff, F. Ronquillo, K. Lucero, E. Corriveau, B. Vanleit, D. Alverson, and A. Scott. 2010. Health extension in New Mexico: An academic health center and the social determinants of disease. Annals of Family Medicine 8(1):73-81.

New Mexico Department of Health. 2010. Racial and ethnic health disparities report card. Santa Fe: New Mexico Department of Health.

NIFA (National Institute of Food and Agriculture). n.d. Extension. http://nifa.usda.gov/ extension (accessed July 6, 2015).

Schroeder, S. 2007. Shattuck lecture. We can do better—Improving the health of the American people. New England Journal of Medicine 357(12):1221-1228.

United Health Foundation. 2015a. America’s health rankings. http://www.americashealthrankings.org (accessed August 12, 2015).

United Health Foundation. 2015b. America’s health rankings: A call to action for individuals and their communities. Minnetonka, MN: United Health Foundation.

UNM (University of New Mexico). 2015. HSC vision, mission and core values. http://hsc.unm.edu/about/mission.shtml (accessed August 11, 2015).

WHO (World Health Organization) and GHWA (Global Health Workforce Alliance) Secretariat. 2013. A universal truth: No health without a workforce. Third global forum on human resources for health report. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.