2

Curriculum Redesign and Restructuring

Key Messages Identified by Individual Speakers and Participants

- Many programs could decrease costs by minimizing duplication of efforts. (Asprey)

- A major obstacle to getting started [with curricular redesign] was identifying faculty with the appropriate training and background in health system science to implement the program. (Baxley)

- It is important for a patient-centered health care delivery system to be supported by health care professionals working in teams that include families, communities, and other resources. In this way, the whole becomes interdependent and greater than the sum of its parts. (Wolpaw)

- We need to be listening to the people in the communities—patients, families, community leaders, and organizations—and bring forth a new vision particularly related to culture and community needs and assets, so the experiences of the health professions, while they are going through their education, is authentic. (Mancini)

Susan Skochelak heads the Accelerating Change in Medical Education initiative at the American Medical Association (AMA). This initiative

funded 11 curricular innovations at medical schools.1 Grantees were asked to transform medical education to prepare students for tomorrow’s health care environment through bold, rigorously evaluated innovations. Too often, said Skochelak, educators’ reforms stay within the same curricular structure. What she encouraged in her grant recipients was to introduce real reform to health professional education (HPE) that goes beyond “tinkering around the edges.” She sought radical, fundamental dramatic changes in health care that started with curriculum redesign.

Two of the four panelists, Therese Wolpaw and Elizabeth Baxley, introduced by Skochelak in the session on models of partnerships inside and outside of academia, were the AMA grant recipients. And while all the speakers are part of programs that address interprofessional health education, the focus of this session was on curriculum structure and design. Each speaker was asked to envision health care education for a future workforce.

A MODEL FOR EDUCATIONAL EFFICIENCIES

David Asprey, Ph.D., PA-C

University of Iowa

David Asprey’s presentation described the importance of educational efficiencies. He began by recognizing that educating health professionals is a time- and resource-intense activity. A lot of energy goes into establishing and maintaining human resources, facilities, and finance systems in order to produce a workforce that is believed to be ready to meet the needs of its nation. Asprey also acknowledged that many programs could decrease costs by minimizing duplication of efforts (see Box 2-1). This is particularly critical as education attempts to better model the collaborative nature of today’s health care with its emphasis on efficiency and improved outcomes through team-based care.

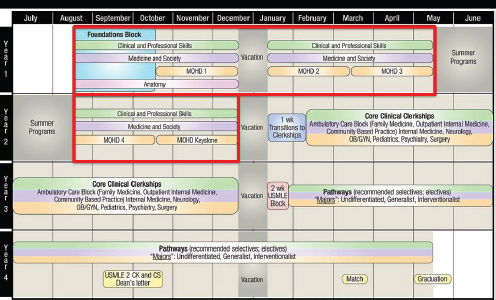

The example Asprey used to describe how such efficiencies might be realized in education was drawn from the University of Iowa’s Department of Physician Assistant Studies. Because the training model for physician assistants (PAs) is similar to the training model for medical doctors, it appeared a natural fit to combine curricular efforts with the university’s medical school. Over time, both curricula were modified and revised so in the fall of 2014, a curriculum was implemented with very few unintegrated courses for years 1 and 2. The red boxes in Figure 2-1 are the first three semesters of the 4-year medical school curriculum where PA students and medical students now take those courses together.

________________

1 For more information about the Accelerating Change in Medical Education initiative at the AMA, visit changemeded.org (accessed July 7, 2015).

BOX 2-1

Why Is Educational Efficiency Important?

- Education of health professionals is a time- and resource-intense activity.

- Combined curricular activities can reduce duplication of effort and resources.

- Health care is a team effort. Educational efficiency reduces training in isolation (silos).

- There are demonstrated benefits from interprofessional team care, and value in learning about, from, and with each other’s professions.

SOURCE: Asprey, 2015.

FIGURE 2-1 Carver College of Medicine: Mechanisms of health and disease curriculum.

NOTE: CK = Clinical Knowledge; CS = Clinical Skills; MOHD = Mechanisms of Health and Disease; OB/GYN = obstetrics and gynaecology; USMLE = United States Medical Licensing Examination.

SOURCE: Asprey, 2015, courtesy of Carver College of Medicine, Office of Student Affairs.

Part of their newly integrated program involved “learning communities” where students from both schools and all years of education are assigned to one of four learning communities. These groups are staffed by a faculty director, a curriculum/community manager, and support staff, but it is the students themselves who initiate and provide leadership for community-engaged service activities (UI Carver College of Medicine, 2014). Such collaborative activities expose students to the other health profession through experiential, interprofessional learning and sharing.

Students’ didactic co-learning decreased course duplication and maximized resources while the combined learning communities provided opportunities for learning from and with the other profession. Asprey considered this a success, but others raised concerns initially about the program. These concerns and Asprey’s responses are listed in Table 2-1.

In closing, Asprey described some lessons learned. As with any interprofessional intervention, leadership was crucial to the success of his program. Asprey described supportive deans that set the tone for the institution. And while the University of Iowa chose to create a total emersion curriculum, Asprey does not believe that is the correct decision for all institutions seeking to create efficiencies through curriculum redesign. For many years, their program was a hybrid version where particular courses were selected for educating the two professions together. This provided some cost savings and some opportunities to bring different students together. Asprey emphasized the value of learning communities for IPE. These can be especially useful for engaging a variety of different professions whose curricula are impossible to match. And finally, Asprey encouraged others

TABLE 2-1 Concerns Raised and Asprey’s Responses

| Concerns | Asprey’s Response | |

| A loss of professional identity among the students | This is a common misconception about interprofessional education (IPE) that Asprey counters by emphasizing that each profession has the appropriate role modeling and stresses unique aspects of each profession. | |

| More frequent student requests to change their field of study to another profession | Students are already asking to change their degree programs. Asprey has not witnessed any increase in these requests. | |

| Students with different backgrounds and academic preparations will not be able to perform at the same level | Both programs admit qualified candidates who can handle the course load; this has not been a problem. | |

| Accreditation will be an obstacle | Many accrediting agencies require IPE activities. It is up to faculty to create purposeful curricula for their students. | |

to look at the comparative advantage of the facility they are working in to identify interprofessional opportunities that make the most sense in terms of the unique structure of their institution.

DEVELOPING FACULTY SKILLS FOR DESIGNING CURRICULA

Elizabeth G. Baxley, M.D.

East Carolina University Brody School of Medicine

Elizabeth Baxley is the senior associate dean for Academic Affairs at East Carolina University Brody School of Medicine. She grounded her remarks on faculty development by explaining that educators have not kept pace in implementing what she referred to as the “new health system competencies.” These competencies would include such curricular topics as patient safety, quality improvement, team-based care, and population health system science. As 1 of the 11 AMA grant recipients under their Accelerating Change in Medical Education initiative, Baxley and her Brody colleagues had the opportunity to carry out their ideas. The outcome of their radical thinking was the Redesigning Education to Accelerate Change in Healthcare (REACH) program.

The REACH program sought to integrate longitudinal education in patient safety, quality improvement, team-based care, and population health into the core medical school curriculum (AMA, 2014). It also emphasized student development of interprofessional and leadership skills. Baxley emphasized the importance of integration when developing the REACH program. She and her colleagues vertically integrated their curriculum throughout 4 years of students’ education to purposefully avoid creating a siloed curriculum. But she also recognized the desire from a subset of her students to better understand the broader health care system, which prompted the project team to create a separate distinction track for advanced training in leadership development called LINC, for Leaders in Innovative Care.

It became quickly apparent that a major obstacle to getting started was identifying faculty with appropriate training and background to implement the program. As a result, the first year of the 5-year initiative was devoted to faculty development. This is the opposite of how curriculum change typically takes place. Usually, a curriculum is designed by a small group of educators then expert faculty is recruited and provided training on how to teach the material. Baxley’s group flipped this process. They selected a core group of faculty members to be part of the school’s year-long professional development program known as the Teachers of Quality Academy (TQA).

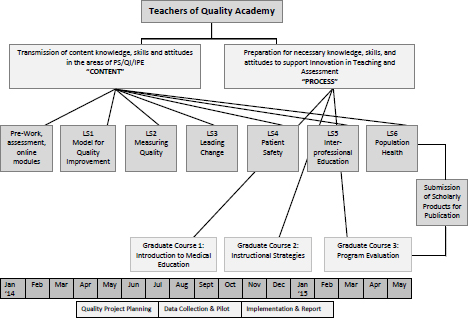

Through the TQA, faculty developed their skills for designing curricula, and for implementing new education and practice designs around these new health system competencies. But much of their time was devoted to

learning the principles and practices of patient safety, quality improvement, team-based care, and population health themselves. Figure 2-2 depicts some of the online prework they completed using Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) Open School material. This was followed by six 2-day interactive learning sessions. In between each session, the TQA members worked in teams to develop and carry out a quality improvement project in the health care system using their newly acquired knowledge. Following this, the TQA members participated in a three-course credential program of graduate courses provided by East Carolina University’s College of Education. This was designed to provide faculty who had not had major roles in curriculum design, implementation, and evaluation an opportunity to learn how to “do” the process of designing educational programs.

Twenty-eight of the original 39 TQA enrollees completed the entire program. The graduates included faculty from medicine, nursing, public health, and allied health who were each nominated by their leadership. This ensured Baxley that her participants—who ranged from senior residents to senior faculty from health care and from education—would have their leadership’s support throughout the year-long training.

FIGURE 2-2 The Teachers of Quality Academy faculty.

NOTE: IPE = interprofessional education; PS = patient safety; QI = quality improvement.

SOURCE: Baxley, 2015 (copyright Elizabeth G. Baxley, M.D., East Carolina University).

Members worked in teams to develop health care quality improvement projects with peer coaching and support for learning and applying the new competencies in an interprofessional environment within their relevant clinical discipline or environment. In addition to this team-based work, there was an online distance educational program created by the university’s college of education on curricular design and evaluation. Baxley was amazed at how traditional silos were crossed as individuals began learning from each other and sharing and challenging ideas through discussion boards and small-group interactions.

Changes in the clinical environment were the first effects to be realized. These included a drop in re-admission rates, reductions in unnecessary radiation exposure, and improvements in handoffs within the health care system and between the acute care and outpatient systems. In all, 28 quality improvement efforts continued beyond the length of the TQA. Within education, the TQA participants have a much greater appreciation and understanding of educational program planning, which led to the development of new curricular products and new partnerships for quality improvement. Eight of these examples that showed clinical or educational improvements have already been presented at national meetings.

Baxley noticed that as the year went on there was a greater reliance on peers as educators, which gave her hope that the established relationships would be sustainable beyond the year of training. She also identified some key lessons learned from her experience setting up and running the TQA (see Box 2-2). But probably the greatest lessons involved understanding the amount of hands-on mentoring that was required and the value of asynchronous communication for improving peer-to-peer exchanges for

BOX 2-2

Key Lessons Learned from the Teachers of

Quality Academy Program

- Teaching while practicing while learning is particularly hard with increasing clinical demands.

- Cohort selection requires establishment of a clear contract with fellow and sponsor for time and effort.

- Design, cognitive preloading, and ongoing mentoring are critical features.

- Use of an asynchronous platform enhanced communication.

- Interprofessional faculty enhanced the team approach to learning and teaching partnerships, and stronger academic teams emerged.

SOURCE: Baxley, 2015.

breaking down interprofessional barriers and moving the group toward greater reliance on peer support.

STUDENTS AS PATIENT NAVIGATORS AND

COORDINATORS PROGRAM

Therese Wolpaw, M.D., M.H.P.E.

Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine

Therese Wolpaw is the vice dean for educational affairs at the Pennsylvania State University (Penn State) College of Medicine. In setting the stage for her presentation on students as patient navigators, she emphasized the importance of a patient-centered health care delivery system supported by health care professionals working in teams that include families, communities, and other resources. In this way, she said, the whole becomes interdependent and greater than the sum of its parts.

It is within this supportive environment that Wolpaw described her curriculum redesign that bolsters and strengthens the pillars of the humanities and the system sciences. Her goal was to help students experience the health care system through the patients’ eyes. To do this, she needed to start with students the moment they walked through her door.

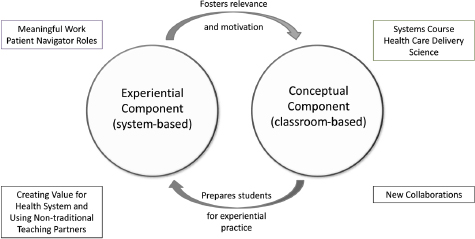

The curriculum design she and her colleagues developed was called Systems Navigation Curriculum (SyNC). As shown in Figure 2-3, it is composed of two parts that connect conceptual classroom work with experiential learning.

The in-class, 18-month systems course takes place weekly throughout

FIGURE 2-3 Penn State’s Systems Navigation Curriculum (SyNC).

SOURCE: Gonzalo et al., 2015, as presented by Wolpaw on April 23, 2015.

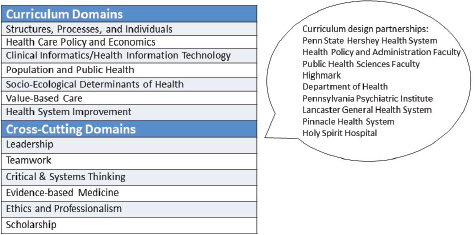

FIGURE 2-4 Systems course health care delivery science.

SOURCE: Gonzalo et al., 2015, as presented by Wolpaw on April 23, 2015.

the first 2 years. While it includes large-group framing sessions, most of the learning takes place through facilitated small groups. For the experiential learning component, students are placed in health systems around central Pennsylvania as patient navigators. These educational components occur simultaneously so students are learning concepts in the classroom that can be immediately applied in their role as patient navigators. As patient navigators, the students experience the value and the problems with the health system. Their observations are brought back to the classroom for more in-depth exploration in small-group settings.

Figure 2-4 shows the classroom component of the curriculum that is a systems course in health care delivery science. It was a challenge initially to determine the content of a course so new that it had no previous model upon which to build. This course is made up of 13 domains; 6 of these cut across all learning and include areas such as leadership and teamwork. Wolpaw and colleagues were able to identify partners outside of the educational system to participate in the course. For example, the Penn State Hershey Health System administration is a partner as well as the Department of Health.

For the experiential piece of the curriculum, students go into the community and work as patient navigators. They learn the skill and art of guiding patients to overcome barriers that are imposed by a fragmented health care system. These barriers are numerous and might involve a variety of issues such as:

- literacy,

- cultural differences,

- communication,

- social isolation/networks,

- financing health care,

- appointments and follow-up, and

- transportation.

Students are placed at 24 sites in 9 different health systems throughout central Pennsylvania. They are in Lebanon Valley Clinic, which is a clinic for the noninsured, and the Pennsylvania Department of Health. Students are in the Pinnacle Heath System in Harrisburg where students experience care coordination for a variety of health complications ranging from heart failure to spinal disorders to kidney disease. Students are exposed to care settings in the Penn State Hershey system such as the psychiatric institute, family medicine clinics, bundled payment clinics, weight loss clinics, and cancer clinics. In 2015, students will also be placed at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center and the Penn National Racetrack assisting migrants. Before serving as patient navigators, students are given the card shown in Box 2-3 to orient them to their role as patient navigator and to outline the skill set they will need to develop.

What is most remarkable about this curriculum, Wolpaw said, are the teachers. These are nontraditional teaching partners, both inside and outside of academia, including care coordinators, patient navigators, nurses, and case managers. This provides students an opportunity to see and experience patient care through many different kinds of providers within the interprofessional health care team. To orient students in their roles as patient navigators, the Penn State program brought patient navigators into the classroom. In addition, students work with standardized patients who take on the role of high-utilizer patients. The students have an opportunity in the classroom to interview these standardized patients then go to a large group setting, where a real patient navigator interviews that same standardized patient. The students have the opportunity to compare and contrast their interview with someone who has much greater experience. Students and patient navigators both write the story of the patient they interviewed so once again, students can compare and contrast their work with someone who possesses much greater experience than themselves. Wolpaw expressed her belief that the model also has global possibilities. Penn State has a partnership with Mountcrest University in Ghana. The founders are very committed to creating humanistic physicians to better serve the people of Ghana. Through their partnership, faculty from both institutions have made visits to the other’s university to enhance shared learning.

In her opinion, this curriculum will stimulate students to be change agents in decreasing barriers around access to care. The students, by partnering with patients and service extenders, gain a better understanding of the health care system and how it might be changed. Over time, this

BOX 2-3

SyNC Patient Navigator Cards

Building the Patient Story

Life story: Can you tell me a little about yourself? I’m interested in your story—growing up, family, work, hobbies, things like that. What is most important to you?

Illness experience: What has this illness been like for you? What has been hardest? What has helped you? What are you hoping for?

Explanatory model: I am interested in hearing what you are thinking about your medical problem. What do you think is going on? What do you worry about the most?

Navigator Cycle

Getting and building the story

- Listening

- Seeking out the backstory

Making a diagnosis

- Identifying challenges and barriers

- Contexts: individual/family, social network, community, society

- Targets: disabilities, housing, support, transportation, finances, insurance

- Asking why

Telling the story

- Communicating with the interprofessional team

- Navigator hand-offs

Making a difference

- Creating and implementing a plan

- Empowering the patient—shared decision making and accountability

Reflecting

- Identifying boundaries: What is your role? What are your limitations?

- Critiquing personal assumptions, biases, and learning needs

SOURCE: Wolpaw, 2015, courtesy of Penn State College of Medicine System Navigation Program.

will lead to more thoughtful resource use and increased patient access to services. But the most compelling aspects of the curriculum to Wolpaw are the changes she witnesses in her students. Students feel empowered to assist patients in navigating a fragmented health care system and to take a leadership role in improving the system. She believes the creation of humanistic,

systems-thinking medical students will lead to physicians who are integral members of a well-functioning, patient-centered, systems-oriented health care team.

VALUE IN PARTNERSHIPS

Timi Agar Barwick from the Physician Assistant Education Association facilitated two table discussions that drew individual opinions and thoughts from participants at the workshop. The questions she presented delved more deeply into the topic of “new partnerships.” Each table discussion was interprofessional2 and drew ideas from a variety of perspectives that informed all those who participated; however, the comments noted in Tables 2-2 and 2-3 are those of the individual respondent and should not be considered a group consensus.

TABLE 2-2 Educators of the Future

| Respondent | Affiliation | Who Are the Educators of the Future, and How Will Their Roles Be Different from the Traditional “Teacher”? |

| Mary (Beth) Mancini | Society for Simulation in Healthcare | Everyone |

| “We need to be listening to the people in the communities, patients, families, community leaders, and organizations, and how we actually bring a new vision particularly related to culture and community needs and assets, so that the experiences of the health professions, while they are going through their education, is authentic. Also, we need to think about this community educator as both dealing with the individual health profession student and ultimately the health professions academy. Unless the academy changes, we will not have true interconnection between the academy and the community. If we do not educate the educators, we will never be able to maximize the ability for the community to be the faculty and the educators of our students of the future.” | ||

________________

2 The participants at the workshop included representatives from allied health fields; communication sciences; complementary and alternative health; dentistry; medicine; mental health counseling; nursing; nutrition and dietetics; occupational therapy; optometry; pharmacy; physical therapy; physician assistants; psychology; public health; social work; speech, language, and hearing; and veterinary medicine.

| Respondent | Affiliation | Who Are the Educators of the Future, and How Will Their Roles Be Different from the Traditional “Teacher”? |

| Andrew Pleasant | Canyon Ranch Institute | Everyone |

| “It is going to include people you might not suspect, like engineers and IT [information technology] professionals and business administrators and architects to build not only a health workforce, but a health city for people to live in. . . . It also extends into the community so that people, formerly known as patients, will be teaching health professionals how to do their job. This will better integrate learning and service throughout the entire curriculum.” | ||

| Christopher Olsen | University of Wisconsin–Madison | The interprofessional team across disciplines |

| “By doing that, we will, in the individual profession, avoid recreating wheels and the idea that we need a flatter world view culturally. We are all learners. An additional aspect is the role of technology that might include new platforms like Google Glass, Apple Watch, online simulations, and crowdsourcing of patient input through virtual connections.” | ||

| Timi Agar Barwick | Physician Assistant Education Association | Knowledge management educators and quality-minded professionals |

| “Knowledge management educators are people who can teach students how to get knowledge efficiently and then how to use it in terms of their decision making. Quality-minded professionals are those who focus on quality or quality improvement and how such concepts can be applied across curricula.” | ||

| Respondent | Affiliation | Who Are the Educators of the Future, and How Will Their Roles Be Different from the Traditional “Teacher”? |

| Deborah Trautman | American Association of Colleges of Nursing | A learning community that includes patients, community members, and health system users |

| “In an effort to create lifelong learners, educators of the future are going to form learning communities that include patients and other individuals in the community and in the health system. It will take in many more perspectives than what we currently have. The radical change will be to bring the education process out into the community. The tactics and strategies for accomplishing this will continue to evolve to be more technology focused and more available in response to the 24/7 environment we live in. Educational leaders will also change, moving from a faculty-guided system to one that emphasizes learner-guided education. Faculty will be the facilitators of learning similar to what we have already seen with the flipped classroom. We will be moving from the ‘sage on the stage’ to a ‘guide on the side.’ | ||

| Also, education will be more experiential and will follow health system paradigm shifts from a disease management, silo-based care system to one that focuses on a person’s wellness through collaborative and team-based efforts.” | ||

| Respondent | Affiliation | Who Are the Educators of the Future, and How Will Their Roles Be Different from the Traditional “Teacher”? |

| Susan Skochelak | American Medical Association | Selves |

| “There is a terrifying and brave new world of self-education that includes Wiki and peer education, which is the dominant force now and will continue to be dominant. While this is probably a good thing, it puts faculty in a new position of needing to understand how best to deliver education that maximizes student learning. What has to be taught face-to-face and experientially learned versus taught online? By understanding these components, one can begin to differentiate between what faculty can offer in all the new educational modalities that continue to evolve, and what must remain core to the education of health professionals.” | ||

| Elizabeth Baxley | East Carolina University | Everyone previously mentioned plus community leaders and nonhealth professionals |

| “While interprofessional learning across the health professions is valuable there are also benefits from learning with those outside of the health professions, like industrial engineers. In addition, people in communities are important educators. The question is how do we engage with communities and their leaders particularly around issues of language and cultural concordance? For example, how might we better work with the Hispanic community and with community advocates? | ||

| A word of caution is that we have to be very cognizant not to use community members solely for the benefit of our students. Goals set by community leaders are of equal importance to the university’s. These need to be set in order to avoid the perception that universities only reach out to communities when they have a grant or are changing a curriculum. By working together, mutual benefits can be realized.” | ||

TABLE 2-3 Impacts of Evolving Roles

| Respondent | Association | How Will These Evolving Roles Impact the Educational Process and the Community? |

| Mary (Beth) Mancini | Society for Simulation in Healthcare | A healthier community |

| “Numerous new educators of the future have been mentioned, including quality professionals, people in communities, peers, self-learners directing their own education, and knowledge workers teaching how to work with knowledge system engineers. The ultimate value of all work in this area is in creating healthier communities although the impact on the education process would also be significant. This would involve creating true partnerships that place more of the power and influence within the community and less within the academic setting.” | ||

| Andrew Pleasant | Canyon Ranch Institute | A paradigm shift to thinking of people (formerly known as patients) and communities as equal partners |

| “Being ‘people-centered’ and believing that communities are equal partners in education would diminish the use of models that portray community members as dependent and needy so that people are not depicted as being a deficit to the health care system or lacking in something the health care system values. Such an approach could realign the systems that are perhaps best thought of as a public good.” | ||

| Christopher Olsen | University of Wisconsin–Madison | Shifting the focus from reducing disease to improving wellness |

| “By engaging with communities, we can move the system from a focus on reducing disease to a focus on improving wellness around issues such as food, transportation, the built environment, and the diversity of the health workforce. And in terms of impacts on the educational process, these shifts will necessitate changes in leadership, educational governance and accreditation processes.” | ||

| Respondent | Association | How Will These Evolving Roles Impact the Educational Process and the Community? |

| Timi Agar Barwick | Physician Assistant Education Association | More effective use of resources |

| “Broadening the competency base of faculty and providers through the inclusion of ‘new educators’ could expand perspectives and adjust the roles of traditional teachers. This would call for more effective utilization of resources that could add value to the education enterprise and to the community.” | ||

| Deborah Trautman | American Association of Colleges of Nursing | Improve social cohesion for improved health and wellness |

| “Health literacy and the educational process are essential elements to improving social cohesion that is based on solidarity, equity, compassion, and caring for others. The impact is improved health and wellness where health is the state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not nearly the absence of disease or infirmity.” | ||

| Susan Skochelak | American Medical Association | Greater financial support to communities and patients |

| “Changing the financial model so dollars are spent on new ways of teaching. That means getting support into the community, to the patients, and to the newly designed faculty. It also means financially supporting learning and interventions that address upstream determinants of health that could move communities toward more positive changes.” | ||

| Arthur Kaufman | University of New Mexico | A change in the power balance |

| “Taking inspiration from the Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs), where at least 51 percent of academic health centers’ boards and advisory committees must be consumers of services at their clinic, the power would shift away from campus to communities. This would bring academic centers closer to communities and investment dollars more in line with community needs. Changing the power balance would create an effective learning environment.” | ||

REFERENCES

AMA (American Medical Association). 2014. AMA MedEd update, February, 2014: Faculty trained to teach team-based care to physicians of tomorrow. http://www.ama-assn.org/ams/pub/meded/2014-february/2014-february-top_stories3.shtml (accessed July 7, 2015).

Asprey, D. 2015. A model for educational efficiencies. Presented at the IOM workshop: Envisioning the Future of Health Professional Education. Washington, DC, April 23.

Baxley, E. 2015. Faculty development for improving system teaching and curriculum design. Presented at the IOM workshop: Envisioning the Future of Health Professional Education. Washington, DC, April 23.

Gonzalo, J. D., P. Haidet, K. P. Papp, D. R. Wolpaw, E. Moser, R. D. Wittenstein, and T. Wolpaw. 2015. Educating for the 21st century healthcare system: An interdependent framework of basic, clinical, and systems sciences. Academic Medicine.

UI (University of Iowa) Carver College of Medicine. 2014. MD program: Learning community FAQ. http://www.medicine.uiowa.edu/md/communitiesfaq (accessed July 7, 2015).

Wolpaw, T. 2015. Students as patient navigators and coordinators program. Presented at the IOM workshop: Envisioning the Future of Health Professional Education. Washington, DC, April 23.